17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

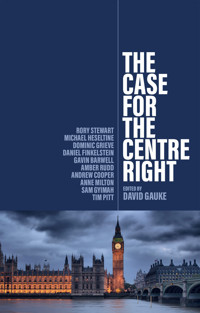

In recent years, the once familiar landscape of British politics has fundamentally changed. The Conservative Party in particular has undergone a profound transformation. Centre-right values that steered British politics for decades - internationalism, respect for the rule of law, fiscal responsibility, belief in our institutions - were cast aside in the wake of the Brexit referendum to the detriment of UK prosperity, electoral trust and the long-term fortunes of the Conservative Party. But this radical rightwards shift can and must be reversed. In this bold intervention, David Gauke and other leading figures on the centre right - including Michael Heseltine, Rory Stewart, Amber Rudd, Gavin Barwell and Daniel Finkelstein - explore how the Conservative Party morphed into a populist movement and why this approach is doomed to fail. Together they make the case for a return to the liberal centre right, arguing with passion and conviction that the values that once defined the best of British conservatism remain essential both to the party and to the UK's political future.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

About the Authors

Introduction

How Brexit changed everything … and the forces that led to it

The rising tide of populism

The economy

Internationalism

Why the liberal centre right remains necessary

Notes

1. The Realignment of British Politics

Open vs. closed

The politics of nostalgia

The big lie of Cakeism

Volte face

Becoming a single-issue party

Brexit denial

Conclusion

Notes

2. Populism’s Price

The break from the liberal centre right

The populist turn

The way back

3. Restoring the Rule of Law

Human rights

The Brexit effect

Reasserting the rule of law

Notes

4. Fixing a Bad Brexit Deal

How we got here

What does ‘here’ look like?

Has Brexit been a success?

What do the public and business think?

So what to do?

Conclusion

Notes

5. A Renewed Agenda for Conservative Economics

Principles for Conservative economics

The UK economy’s challenges

Renewed Conservative economics in practice

Macro-economic framework

Conclusion

Notes

6. Tackling the Health Crisis

Keeping people well

The politics of improving health

Getting rid of siloed government and the dead hand of Whitehall

Living with economic reality

Enabling access for all to world-class healthcare

Paying for services

Providing the service

New technologies

Caring for the elderly

Paying for personal social care

Bed blocking

Devolving decision-making

The centre right agenda for the health of our nation

Notes

7. Winning the Global Race for Science and Technology

No more karaoke Thatcherism

Vision for the future

Galvanising private capital

Institutional and regulatory architecture

The brightest and the best

Planning

Conclusion

Note

8. The Future of Climate and Energy Policy

A strong start under Cameron

Watering down the Green agenda

Building on Paris

The challenge ahead

Uniting the party behind net zero

The trilemma

Conclusion

9. A pro-European and pro-Devolution Agenda

The harms of Brexit

Not so splendid isolation

A responsible approach to immigration

The role of the state in the economy

Devolving power

Conclusion

10. What Divides the Centre Right from the Centre Left (and what doesn’t)

The core politics of the centre

Compromise and Complexity

Different kinds of centrists

Centre right and centre left

Political divisions

Conclusion

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 4

Figure 4.1

The cost of Brexit (GDP)

Figure 4.2

The impact on goods trade with the EU

Figure 4.3

The impact on business investment

Figure 4.4

Public opinion: In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vot…

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

About the Authors

Introduction

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

The Case for the Centre Right

Edited byDAVID GAUKE

polity

Copyright © David Gauke 2023

The right of David Gauke to be identified as Editor of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2023 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6083-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023938220

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

About the Authors

David Gauke is a former Conservative MP and cabinet minister, serving as Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Work and Pensions Secretary, Justice Secretary and Lord Chancellor. He lost the Conservative whip for opposing a no deal Brexit and fought the 2019 general election as an Independent. He is now a regular columnist for the New Statesman and ConservativeHome.

Andrew Cooper served as Director of Strategy to Prime Minister David Cameron during the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government. He is founder of the polling consultancy Populus and advises businesses and campaigns on strategy. He was appointed to the House of Lords in 2014 as Lord Cooper of Windrush. He is also a visiting lecturer at the London School of Economics.

Rory Stewart is President of GiveDirectly and the co-presenter with Alastair Campbell of The Rest Is Politics. He was an MP from 2010–19, serving as a minister in DEFRA, DfiD, FCO and MoJ and finally as Development Secretary. Before entering politics, he served as a British diplomat, ran a charity in Afghanistan and had a chair at Harvard University. His books include the New York Times bestseller The Places in Between, which records his 21-month walk across Asia.

Dominic Grieve is a barrister and King’s Counsel and a visiting Professor at Goldsmiths, University of London. He was MP for Beaconsfield from 1997 to 2019, sitting as a Conservative before becoming an Independent, as a result of having the whip withdrawn over his opposition to a no-deal Brexit. He was Attorney General for England and Wales from 2010–14, served in the government of David Cameron and was Chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament from 2015–19.

Gavin Barwell had a long career in Conservative politics, serving as the party’s Director of Campaigning, the MP for Croydon Central from 2010 to 2017, a government minister and Downing Street Chief of Staff for the last two years of Theresa May’s premiership. He has written about the latter experience in Chief of Staff: Notes from Downing Street. He is the co-founder of NorthStar, which advises global businesses on geopolitical risk.

Tim Pitt served as a special adviser at the Treasury to Chancellors Philip Hammond and Sajid Javid. Since leaving the Treasury in 2019, Tim has been a partner at the business consultancy Flint Global and written widely on economic and fiscal policy, including for the Telegraph and the Financial Times. He is also a Policy Fellow at the think tank Onward. Prior to going into politics, Tim was a corporate lawyer at the City firm Slaughter and May.

Anne Milton is a former nurse who worked in the NHS for 25 years before being elected as a Conservative MP. She was a Minister for Public Health, Minister for Skills and Apprenticeships and Government Deputy Chief Whip. She now chairs a Social Value Recruitment Board for PeoplePlus; is an associate for KPMG; Chairs the Purpose Health Coalition; and is an advisor to PLMR. She continues to work for a number of organisations on skills and further education.

Sam Gyimah served as a government minister with responsibility for higher education, science, research and innovation, and was Parliamentary Private Secretary to David Cameron. Elected to parliament in 2010, he was the Conservative MP for East Surrey from 2010–19 and, for a brief period at the end of 2019, he was a Liberal Democrat MP. Sam started his career as an investment banker and continues to advise a number of venture capital and private equity firms with a focus on geopolitics and financing the innovation economy. He is also a non-executive director of Goldman Sachs International.

Amber Rudd is a former politician who held cabinet roles under David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson. As Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, she led the UK delegation at the Paris Climate agreement in 2015. She left parliament at the end of 2019 and pursues a career in the energy transition working in the private sector and on policy initiatives to influence government policy.

Michael Heseltine was a member of parliament from 1966 to 2001. During this time he held various cabinet positions, including First Secretary of State and Deputy Prime Minister under John Major. He has continued to work and publish on issues of growth, industrial strategy and devolution. A fierce campaigner for Remain, he became President of The European Movement in 2019. He is also founder and Chairman of the Haymarket Group, a privately owned media company.

Daniel Finkelstein OBE is a columnist for The Times and the author of Everything in Moderation and a family memoir, Hitler, Stalin, Mum and Dad. He provided political advice to Prime Ministers John Major, David Cameron and Theresa May, and was director of policy for William Hague during his time as opposition leader. In 2013 he was appointed to the House of Lords.

Introduction

David Gauke

If one had asked an informed international observer to describe the nature of politics and political opinion in the United Kingdom, until relatively recently the answer would most likely have been along the following lines …

The United Kingdom does not have a doctrinaire antipathy to big government in the way that, for example, might be attributed to the United States, but it is more sceptical than many other European nations. It broadly tends to favour market solutions wherever possible. It is generally cautious when it comes to government borrowing and debt but, if affordable, is keen to maintain competitiveness on matters of taxation.

This stems, in part, from its belief in economic openness. It sees itself as a trading nation, favours lowering barriers to trade, and seeks to attract foreign investment and talent to its shores. Its economy is relatively focused on sectors that are international in character, such as financial services, the creative arts and technology, and this contributes to an outward-looking approach.

It is more generally internationalist in nature, playing a wholehearted role in the defence of its values and allies. It is an enthusiastic member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). As for the European Union, it is clearly sceptical about a federalist vision of a United States of Europe but it has also played a vital and constructive role in the creation of the European Single Market and in enlarging the EU to encompass the nations of eastern and central Europe.

The UK is a nation of strong institutions: parliament, an impartial civil service and an independent judiciary. The rule of law is venerated. The 1970s was certainly a turbulent decade but British politics is largely stable and produces leaders who – while not necessarily perfect – are conscientious, public-spirited, and sensible.

In general, the UK would be described as pragmatic, sceptical of the ideology of left or right, willing to embrace the future but appreciative of the value of continuity. British governments reflected the electorate and, crucially, general elections were usually won by the party that made the most compelling pitch to the centre ground of British politics. More often than not, that party would be the Conservative Party.

Our observer might go on to state that the nature of British politics and the nature of the Conservative Party were closely aligned. For the most part, the Conservatives represented the cautious and pragmatic instincts of the British public. Even when led from the right – as happened during Margaret Thatcher’s time in office – Conservative governments sought to deliver a pro-business environment, a stable and certain political environment, and a constructive relationship with our neighbours. Ministers would be appointed on the basis of their political and administrative abilities, rather than on ideological purity.

The one recent extended period when the Conservative Party was unsuccessful in winning elections was when the party was perceived as no longer representing these values. In the 1997, 2001 and 2005 general elections, the Conservatives were seen, initially, as divided, exhausted and out-of-touch but then, increasingly, as extreme and ideological. Electoral matters were not helped by the fact that the Labour Party was led by Tony Blair, who was viewed by much of the electorate as sharing many of the instincts of moderate Conservatives. The Tories only returned to office after (a) Blair had gone and (b) the Conservatives had engaged on a conscious programme of modernisation that sought to reposition them in the centre ground of British politics.

Even then, the Conservatives failed to obtain an outright majority in 2010 and governed in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. To the surprise of both parties, the Coalition government proved to be remarkably stable and considerable common ground was found between the David Cameron-led Conservatives and the Nick Clegg-led Liberal Democrats.

It did the Liberal Democrats little good. In the 2015 general election their centre left voters abandoned them to support Labour while their centre right voters decided that they might as well vote Tory. With Labour having moved to the left under Ed Miliband, the Conservatives won a parliamentary majority for the first time in twenty-three years. With Labour shortly afterwards moving much further to the left – under Jeremy Corbyn – our observer would most probably have concluded that the Conservatives would be the dominant force of British politics for years to come; and that the liberal centre right would continue to be the pre-eminent force in British politics. Our observer would have been half right. The Conservatives remained in office, albeit losing their majority in 2017, before obtaining a landslide victory in 2019. The values and policies of the liberal centre right – the dominant form of British politics from 1979 onwards – was, however, in decline. British politics was changing. The electorate was already slowly realigning but this process accelerated in 2016 with the Brexit referendum. Under Boris Johnson, the Conservatives leant into this realignment, appealing to voters of a more authoritarian and nationalistic instinct. The choice paid rich dividends for Johnson, delivering an 80-seat majority, the largest Conservative majority since 1987. The Conservatives were dominant but, as this book argues, by and large, the liberal centre right had been marginalised.

The politics of the Conservative Party became more populist under Johnson, followed (briefly) by a period of ill-considered ideological purity under Liz Truss. This left our economy weaker, our standing in the world diminished, our political standards cheapened and our institutions destabilised. Rishi Sunak has repaired some of the damage but leads a party that has not yet fully returned to its mainstream traditions.

The purpose of this book is to argue that the marginalisation of the liberal centre right is detrimental to the country and urgently needs to be reversed.

How Brexit changed everything … and the forces that led to it

The 2016 EU referendum was a pivotal moment in British politics, bringing an end to David Cameron’s premiership and beginning a period of great political volatility. It was a disastrous moment for the liberal centre right. The decision to call a referendum and the result, however, did not come from nowhere. It was the culmination of decades of growing Euroscepticism inside and outside the Conservative Party.

At the time of the first European referendum in 1975, it was the Labour Party that was split and the Conservatives who were overwhelmingly united in support of membership of what was then the European Economic Community. A small minority of Conservative MPs, led by Enoch Powell, had opposed the UK joining in the parliamentary debate of 1972; by 1975 Powell had left the party. The new Tory leader, Margaret Thatcher, had no hesitation in supporting the campaign to stay.

Labour, meanwhile, was more deeply divided. The Labour left – including cabinet ministers such as Tony Benn, Barbara Castle and Peter Shore – campaigned to Leave, while those on the Labour right – such as Roy Jenkins – enthusiastically backed Remain. The Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, recommended remaining but maintained a low profile during the campaign.

With most mainstream politicians, plus most of the newspapers, business and the trades unions favouring a vote to stay in, the British public voted 2–1 in favour of Europe.

By 1983, with people like Jenkins having left Labour to form the Social Democratic Party, Labour had moved to favouring leaving the European Economic Community. The Conservatives, however, remained steadfastly in favour of membership, even if Mrs Thatcher’s relationship with European institutions was not entirely cordial. She won the general election by a landslide. The matter appeared largely settled.

It was during the following parliament that a former Conservative Minister, Arthur Cockburn, as European Commissioner, put in place the European Single Market, which involved member states surrendering their vetoes in order to remove non-tariff barriers. Internal opposition to the move within the Conservative Party was limited to the fringes, and the relevant legislation sailed serenely through parliament.

For the vast majority of Thatcher’s premiership, the UK’s relationship with Europe was not a first-order issue. She was never an enthusiast for close integration within Europe but saw efforts to reduce trade barriers within the European Community as consistent with her beliefs in free trade and free markets.

The mood began to change in the late 1980s, with the pivotal month being September 1988. First, the President of the European Commission delivered a speech to the TUC conference in Bournemouth on 8 September, in which he argued that Europe enabled workers’ rights to be protected. He was well received, indicating that the left was moving away from its Euroscepticism. Second, on 20 September, Margaret Thatcher responded by delivering the Bruges Speech, the founding text of Conservative Euroscepticism.

Read today, the Bruges Speech appears remarkably moderate in that Thatcher declares that ‘our destiny is in Europe, as part of the Community’. But she argues against a federal Europe and raises concerns that Europe is moving in the direction of higher levels of regulation. ‘We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels’, Thatcher declared.

Euroscepticism was now made up of two elements. The first was the longstanding argument about sovereignty. The second was an argument coming from the free market right – that Europe had an agenda that was economically interventionist and anti-markets. To put it another way, Europe was anti-Thatcherite.

It was in this context that a growing number of Thatcher’s strongest supporters became increasingly Eurosceptic. The ignominious nature of sterling’s departure from the Exchange Rate Mechanism – membership of which was a policy advocated by mainstream opinion – only strengthened the confidence of those who questioned the pro-European consensus.

By the mid-1990s, Euroscepticism was a strong force in the Conservative Party, making the life of the Prime Minister increasingly difficult. Thatcherites felt aggrieved at the loss of their political heroine and much of the debate had by this point focused on membership of the Euro, with the bulk of the Conservative Party opposing the UK’s participation. It was one of the few issues on which the Tories were more obviously in line with public opinion than their opponents, even if the public did not see it as a priority issue.

Tory Euroscepticism was strong but it generally still favoured continued membership of the EU. ‘In Europe, not run by Europe’, was William Hague’s slogan, having become party leader following the landslide defeat in 1997. Most Conservatives took the Eurosceptic side of the debate but the debate was not about whether we left the EU but whether we should become more closely integrated into it. For many Eurosceptic Conservatives, thus far but no further was a perfectly satisfactory position.

This remained the default position for many Conservatives, almost until the referendum campaign of 2016. Few Conservative MPs made the case that we would be ‘better off out’ during the coalition years, but distanced themselves from the frontbench by advocating a referendum on EU membership. Such a position went down well with those party members who were unhappy with the inevitable concessions that have to be made in a coalition and who disliked socially liberal policies such as gay marriage. It was also a means of neutralising the threat of the UK Independence Party, led by Nigel Farage, who had become an electoral force in European parliamentary elections.

The demand for a referendum grew stronger. Cameron – mindful of holding the Conservative Party together and believing that resolving the issue in favour of remaining was most likely to happen if the matter was addressed sooner rather than later – announced that a Conservative government would hold an in–out referendum.

This is not a detailed account of the Brexit referendum; however, there are certain points that flow from that period that are important in understanding the current state of the centre right in British politics.

The first, as I have mentioned, is that relatively few Conservative MPs were committed to leaving the EU in advance of the campaign. For some, this was tactical. Steve Baker, for example, was always going to favour leaving the EU but did not announce his position until negotiations were complete, at which point he declared his disappointment at the outcome. Given his absolutist position on sovereignty, he must have known that there was no prospect of the renegotiations satisfying his conditions. For others, who may have identified as Eurosceptics, leaving had not been their biggest priority. But now that the question of membership was in front of them, they gave the Eurosceptic answer, even if it was a very different question from the one that was asked in previous years.

The second, as became apparent in subsequent years, was the widespread naivety about what leaving would mean. Many Leave-supporting Conservative MPs genuinely believed that we would get much the same access to European markets as we had as EU members, even if we no longer had to follow the rules of the Single Market. The German car manufacturers would see to it. As for Northern Ireland, the problems with the border were dismissed. It was not even worth trying to understand the issue.

Some will say this is too generous an explanation. They must have known that we would lose access to EU markets, it was obvious to anyone who understood the issue. Some Leavers, of course, did understand and thought it a price worth paying. But not all. Boris Johnson, for example, according to Dominic Cummings, by autumn 2020 still did not understand the difference between the Single Market and the Customs Union, even though he had led the Leave campaign in 2016, served as Foreign Secretary from 2016 to 2018 and been Prime Minister since July 2019. What hope was there for backbench MPs? Anyway, few expected Leave to win the referendum.

Third, the motivations of Leave-supporting Conservative MPs and many Leave-supporting voters differed. For Conservative MPs, it was about sovereignty but also about delivering the next stage of Thatcherism. It was about deregulation, lower taxes, and removing trade barriers (by which they meant lowering tariffs) with the rest of the world. Britain was going to be more liberated, more entrepreneurial, more buccaneering, freed from the dirigiste tendencies of the EU.

This was not the message conveyed to the electorate by Vote Leave. Leaving meant more money for the NHS and stopping Turkish immigrants. This was not about delivering Singapore-upon-Thames but about going back to a time when we were in ‘control’. It was a campaign designed to appeal to those who disliked change and wanted reassurance.

The casualness with which many Conservatives backed Leave, the ignorance of the consequences of leaving and the inconsistency between what the advocates of Brexit wanted and what many of its voters wanted meant that delivering Brexit became immensely difficult and has left many – both MPs and the public – disappointed. This tension between the free market vision of Brexit and the one that many Leave supporters voted for is one that continues to this day and continues to cause tension on the right of British politics.

The rising tide of populism

Our politics appears to be realigning. As Andrew Cooper sets out in Chapter 1, politics is moving away from the politics of economic class – with those who are economically secure voting centre right and those who are insecure voting centre left – towards the politics of culture. Increasingly, a more reliable indicator of how you vote is not your income but your educational background, and the population density and diversity of your neighbourhood.

It has always been the case that the Conservatives have done relatively well with the rural poor and Labour has done relatively well with the urban rich. But in a trend that has been in place for decades, the Conservatives have won increased support in low density, low diversity, relatively poor locations while retreating from relatively prosperous cities. Ex-mining constituencies in the north Midlands, for example, once voted solidly Labour, even with a Conservative landslide. In general election after general election, these areas have swung towards the Conservatives to a greater extent than the national picture would have suggested. In 2019, Labour was almost wiped out in Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire but for a handful of inner-city constituencies. In contrast, the Conservative performance in London was considerably worse in the 2019 landslide (21 Conservative MPs out of 73) than in 1992 (48 out of 84), when John Major won a small majority.

To some extent, these changes can be put down to economic characteristics. Home ownership is higher outside the big cities, especially London. As James Kanagasooriam, who coined the phrase ‘Red Wall’, has pointed out, if one looked at the demographic make-up of Red Wall constituencies, the surprising fact was that for many years the Conservatives had underperformed in these areas.1 The fall of the Red Wall in 2019 was the culmination of many years in which historical ties to Labour (or historical antipathy to the Tories) had weakened.

Nonetheless, the changing geographical distribution of the Conservative vote has changed the nature of political views of Conservative voters. The Tories have retreated in Remain-voting constituencies and advanced in Leave-voting constituencies. The general election of 2019 saw the parliamentary map better reflect the 2016 European referendum. The Conservatives had become, to a much greater extent, the party of Leave.

This came with considerable advantages in the ‘first-past-the-post system’. In the 2016 referendum, Remain did well in cities, university towns and Scotland; its vote being heavily concentrated in those areas. The Leave vote was more widely distributed, which meant that, according to analysis done by Chris Hanretty, 409 out of 650 parliamentary constituencies voted Leave, even though Leave only obtained 52 per cent of the vote. The Conservatives also benefited in 2019 by the fact that the Remain vote was split between Labour, Liberal Democrat, Green and, in a handful of cases, Independent plus the nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales. With Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party giving sitting Conservative MPs a free run, the Leave vote could rally behind the Tories.

A voting base that leant heavily on Leave voters was not one that embraced the free market vision of Brexit. The 2019 campaign recognised this, with promises of forty new hospitals and 20,000 more police officers. Higher public spending was in order, although little was said about how this was to be funded.

Analysis by UK In a Changing Europe2 provided a fascinating insight into the views of those who switched from Labour to Conservative for the 2019 general election. These voters were asked various questions that enabled them to be placed on a spectrum on economic values (left to right) and social values (liberal to authoritarian). These switchers were notably to the left of traditional Conservative voters on economic issues but also more socially authoritarian.

There is a temptation to dismiss Johnson’s government in 2019 to 2022 as being particularly right wing. It is true to say that on issues such as Brexit and immigration, Johnson sought to govern from the right (although, to be fair, immigration policy for those coming from outside the EU became more liberal) but, taken as a whole, it is more complicated than that. On some issues, Johnson was right wing, on others, such as ‘levelling-up’, quite left wing. In many respects, one could argue that Johnson’s agenda reflected public opinion as whole. Not necessarily coherent and, whether because of Covid or whether because of Johnson’s administrative failures, not much was achieved, but one could argue that he fashioned his own type of centre ground. But it was not the politics of the liberal centre right but the politics of populism.

As Rory Stewart writes in Chapter 2, populism is the politics of setting the people versus the elite. This was the approach that Vote Leave pursued in 2016 and it was the approach that Johnson took on becoming Prime Minister in 2019.

Brexit had not been delivered, according to Johnson, not because the Leave campaign had promised the undeliverable (or even that Johnson and his allies had repeatedly voted down a deal that would have delivered Brexit) but because the elite had blocked it.

Remainer ministers and Remainer civil servants had delivered an inadequate deal. Remainer judges (‘the enemies of the people’) had stood in the way, as had a Remainer parliament, which is why it had to be suspended (not that this was ever explicitly admitted) until the judges (them again) intervened. The people had voted and here we were, more than three years later, still in the EU. It was time to get Brexit done.

It was a clever slogan, appealing not just to diehard Brexiteers but also to those who were tired of the wearisome and prolonged process of leaving the EU. Blame was laid on the elite and their institutions, which had stood in the way of the will of the people. Johnson was presented as the people’s tribune, on the people’s side, willing to bulldoze through any obstacles to deliver the people’s objectives.

It was not a pitch that allowed much room for nuance or subtlety – or, at times, honesty. The inevitable trade-offs involved in governing were dismissed, whether on tax and spend (taxes would be cut, spending increased, borrowing kept under control) or on Brexit. Most egregiously, the government promised that it had a deal on Brexit that would mean no checks on goods crossing the Irish Sea, even though that is exactly what had been agreed.

One particular aspect of the Conservative manifesto was the proposal to reform judicial review. This appeared to have been provoked by the ruling of the Supreme Court that the prorogation of parliament in September 2019 had been unlawful.

Johnson took this badly and wanted to bring the judges down to size. But this reaction was symptomatic of a wider attitude towards the law – that the executive should not be constrained by the judiciary. Laws were for other people.

This manifested itself in a lowering of ethical standards, a common attribute for populists. The Home Secretary, Priti Patel, was allowed to continue in office after being found to have breached the ministerial code (resulting in the resignation of Johnson’s first ethics adviser), attempts were made to change the parliamentary standards system to protect Owen Paterson over breached lobbying rules, and a culture of law-breaking in respect of Covid restrictions was pervasive in 10 Downing Street.

It was also the case that the government considered itself above the application of international law. Having agreed and ratified the Northern Ireland Protocol, the UK was obliged to comply with its terms and, if it wanted to change the terms, do so in accordance with procedures set out in the Protocol. In contrast, during the negotiations of the UK’s future relations with the EU, the government announced plans to change unilaterally the terms of the Protocol, with a cabinet minister explicitly stating that the government was going to breach international law, albeit ‘in a limited and specific way’.

Eventually, this plan was dropped but the proposal was to return in the form of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill. At this point, the government argued that it was acting in accordance with international law, albeit few lawyers agreed. Support for the rule of law – including international law – has been a fundamental aspect of mainstream political opinion for a very long time. Margaret Thatcher once declared that the UK’s role in the world was to be an advocate for international law. As Dominic Grieve makes clear in Chapter 3, the Johnson government, in particular, failed to meet the standards we should expect.

The extent to which the UK should comply with its international obligations remains a contentious issue for some, particularly in the context of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). For some on the right of British politics, the ECHR imposes unacceptable constraints on the actions a government might want to take, especially in the context of the treatment of asylum seekers. But to leave the ECHR would place the UK in a very small and undesirable club of European nations, alongside Belarus and Russia.

Since its creation in the 1950s (influenced heavily by Conservative politicians), the UK – with the vast majority of democratic European nations – has viewed the ECHR as a buttress to support the rights of the individual and to constrain over mighty governments. Likewise, judicial review has protected the rights of individuals, ensuring that public authorities act reasonably and within their powers. This did not always go without complaints by ministers from all parties but there was recognition that in a modern society, power should be disbursed and checks and balances should be in place. For some on the populist right, this recognition is now contested.

The economy

The dominance of the centre right in UK politics has very largely been based on the British public’s view that the Conservatives could be trusted on the economy. Conservatives would be cautious with the public finances, focused on the need to create wealth not just redistribute it, supportive of aspiration, pro-business and practical.

This is not to say that the public thought that the Conservatives got everything right – evidently they did not – but, in comparison with the ideological dogma, trade-union capture and wishful thinking associated with the Labour Party, the Conservatives won the support of the majority of voters who prioritised economic competence. Again, Labour’s one period of electoral dominance in modern times coincided with Blair’s leadership of Labour when, alongside Gordon Brown, he emphasised New Labour’s commitment to aspiration and prudence.

The last few years have proven to be economically turbulent for most Western economies. The Global Financial Crisis hit the UK hard, had a long-term impact on productivity and living standards, and left the public finances fragile and in need of consolidation. By historic standards, growth during 2010–2016 was weak, although, by international standards, as strong as any nation in the G7, as the world economy struggled to recover from a major financial crisis. In 2020, Covid caused an extraordinary recession across the world, with ballooning public debts and, just as the world economy returned to normality, Russia invaded Ukraine. Energy prices surged, living standards fell.

Any government would struggle in those circumstances. The fiscal consolidation following 2010 has received much criticism, although decisive measures to bring down a deficit of eleven per cent of GDP were necessary. Governments cannot hide away from tough decisions and external shocks meant that the country became poorer than we had previously expected. No government could magically change that. There was, however, a policy that was self-inflicted and unnecessary which has done much economic damage. Recognising this and addressing it is essential if the UK is to prosper in future.

The vote to leave the EU on 23 June 2016 caused an immediate and dramatic fall in the pound which, in turn, increased prices and resulted in a fall in living standards. It also created significant uncertainty, which resulted in business investment (which, hitherto, had been growing strongly) to plateau.

As Gavin Barwell shows in Chapter 4, Brexit was always likely to have a negative economic impact. In addition to the initial impact of greater business uncertainty, making it harder to trade with the EU would result in higher prices, lower business investment, lower levels of trade and (as a less open economy and, therefore, less subject to foreign competition) lower levels of productivity.

How economically damaging Brexit would prove was always going to depend upon the nature of Brexit. As Gavin argues, the unwillingness of Conservative Brexiteers to compromise and seek to minimise some of the economic problems caused by our departure from the European Union has meant that the damage has been greater than it might otherwise have been.

This should be a source of great embarrassment to those who advocated Brexit and then opposed those trying to deal with the consequences pragmatically. There are Brexiteers who argue that an economic cost was a price worth paying to ‘restore sovereignty’ but, at the time of the referendum, warnings of economic detriment were dismissed as ‘Project Fear’. A sensible analysis of the British economy and what it needs to improve its lacklustre performance must acknowledge the damage done by erecting trade barriers with our biggest external market and seek to find ways of reducing those barriers.

The challenge for the Conservative Party is to find a way of doing this without losing the support of those who voted Tory because of their enthusiasm for Brexit. In other words, a party that turned itself into the Leave party has to tell Leave voters that it and its supporters were wrong.

This is not just a problem for the Conservative Party. The most contested voters in the most contested constituencies at the next general election are those who switched from Labour to Conservative in 2019. These are, by and large, Leave supporters and the Labour Party will tread very carefully to avoid offending them. It appears unlikely that either party will acknowledge the obvious economic truth about the consequences of leaving the EU, especially with the thin trade deal that we now have.

The liberal centre right voice has been largely excluded from this debate. Defeated in the referendum, it was the Brexit ultras that prevailed in the long years the followed. Attempts at a compromise deal by Theresa May (which was hardly a ‘soft Brexit’ compared to some of the promises made by Brexiteers