Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

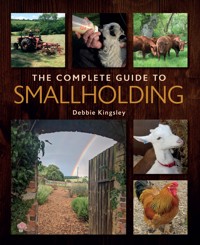

Essential advice from finding your plot to selling your produce and everything in between Growing your own food and living off the land is an aspiration for many, but where do you start and how do you make it work? Providing a truly comprehensive insight and packed with practical guidance for the 21st century smallholder, this book is for anyone considering, starting out or in the throes of smallholding. Addressing the challenges and pitfalls, as well as the joys, and with over 400 illustrations.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 527

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© Debbie Kingsley 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4216 0

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Preparing for the Smallholding Life

3 Land and Accommodation

4 The Legal Aspects of Smallholding

5 Tools and Equipment

6 Fruit and Veg and Foraging

7 Starting with Livestock

8 Poultry and Waterfowl

9 Pigs

10 Sheep

11 Goats

12 Cattle

13 Health and Welfare

14 Meat from the Smallholding

15 Grassland Management and Fencing

16 Making It Pay

17 Making the Most of your Produce and Resources

18 Smallholder Worries

Glossary

Further Sources of Information, Equipment, Reading and Courses

Acknowledgements

Index

1 Introduction

COMING CLEAN

If you’re looking for a bible for complete self-sufficiency, this isn’t it. Just the idea of knitting my own toilet roll or roasting dandelion roots to create a coffee substitute to succour my friends makes me chuckle. I’m not interested in eating cabbage at every meal because it might grow well in our soil, or eating slices from a loaf that sounds, tastes and looks like a brick.

No one could ever give me the epithet of being worthy. I want to eat asparagus cut fresh, moments before the spears go in the pan, and suck raspberries off each finger in greedy glee. I also want a store of stunning beef in the freezer to make a meal of sirloin steak accompanied by field mushrooms gathered that morning and peas fresh from the pod, or a thick slice of gammon glazed with mustard and honey alongside a duck egg pillowed on mayonnaise and scattered with chives with newly dug salad potatoes. I want (I want a lot, don’t I?) vats of cider glugging away in the store room for drinking and for cooking with rare-breed pork with chunks of apple in a casserole, and for turning into cider vinegar that will mutate into blackberry vinegar to accompany salad leaves grown in the polytunnel.

I want, when all’s said and done, to grow, rear and make delicious things and have an interesting, seasonal, nature-observing and enhancing way of life.

A smallholding idyll.

There are so many different ways of smallholding and being a smallholder, and it should not be a way of life that makes a rod for your own back. Just because someone in the next village or on one of the ubiquitous rural life television programmes finds joy in keeping rabbits for the pot, or grows an acre of wheat that they thresh by hand and mill for flour, doesn’t mean you have to. You might yearn for charcuterie without nitrates and have a fancy for pig-keeping, love eating chicken but have a fear of birds (in that case buy oven-ready quality ones from another source and don’t keep poultry), or have a passion for jams and chutneys and be keen to grow fruit and vegetables.

This way of life should not be about wearing a hair shirt as if it only feels real if there’s some suffering in the mix. Stuff that: life is hard enough. If producing the majority of your own food is an all-absorbing ambition, that’s something we share; you have so many possibilities ahead of you, so choose the things that bring you joy.

What I hope this book will give you is a comprehensive insight and guidance into the various elements of a possible smallholding life. Pick and choose the bits that feel right and fit with your life and aspirations, and ignore the parts that don’t (although you can’t ignore everything – if you have livestock or make food for sale there are rules and regulations).

The reason that smallholding is of abiding interest for so many people is precisely because it offers a different way of being, away from the career ladder, commuting and office politicking. Being in charge of every decision is hugely freeing, but the reality is that this way of life has significant ties: this is a 365-days-a-year job (although you can have time out and holidays – we’ll get to that bit later). It’s an opportunity to learn a lot of new things and new ways of doing things, not re-creating the irritations, furies and sadnesses of office life. And because making this way of life pay is something that so many potential and new smallholders want to know about, there’s plenty of grounding, pragmatic information about that too.

THE GOOD SMALLHOLDER

There are certain traits that undoubtedly help make a smallholder. Having a robust constitution, both physical and mental, is undoubtedly helpful, although it’s also clear that smallholding activities can help heal a troubled mind. Machinery is a life-saver when the muscles age and tire or if you have limited strength, but there is no denying that there is a great deal more physicality required in this life than in many others. Some days I can haul a 25kg sack of pig feed over my shoulder and trudge up the track with it, on other days it requires the help of a wheelbarrow.

Having self-discipline is crucial when you have livestock; those chitting potatoes might be able to wait another week before being planted out, but your livestock have to be fed, watered and checked every single day without fail, usually before you contemplate your own breakfast. If poo in whatever form freaks you out, you’ll need to overcome this. Dealing with mortality becomes very real. If, like me, rats make you squeal (this hasn’t improved much in thirty years), you learn to squeak and carry on regardless.

Having an aptitude for, or at least no fear of learning how to make and mend things, whether that is a fence or a goat shed, is helpful. Using hand and power tools is something you’re just going to be doing. You might start off hammering the fencing stake ten times before you manage to hit the staple, but you’ll get there if you hold the hammer properly and don’t close your eyes while you do it.

Having project management skills is surprisingly useful; smallholding is nothing if not a raft of multiple projects with seemingly simultaneous demands on your time, and no boss other than the seasons providing a critical path analysis.

Smallholding is great for the immensely practical person, but it’s also a thrill for those who love a mental challenge: there is so much that you can learn, from land management and enhancement, animal husbandry, midwifery, disease diagnostic skills, fencing, breeding, meat production, using tools effectively – and on and on it goes. Smallholding can keep you intellectually challenged and engaged for life. Unless you come from a farming or veterinary background, the skills and knowledge that you need are not something that most of us learned during our formal education, and there will be a whole swathe of new terminology and confusing equipment to get your head round.

Never has observation and action-based learning been more important as when a life depends on you, whether it be a duckling hatching out in an incubator, or at lambing time. You can (and should) go on some of the excellent courses now available to give you a kickstart and a proper grounding on topics where your enthusiasm outweighs your knowledge by the power of ten. But don’t hop continually from one course to the next without putting into practice some of your new understanding: there comes a point when you just have to get stuck in.

Pilgrim geese in the farmyard.

Learn to use your eyes, ears, nose and hands around your new livestock. My nose alerts me immediately to any case of flystrike if we’re handling the sheep – and more importantly, reassures that we don’t have any problems of that nature. My ears will tell me if a sheep is in distress several fields away – a head stuck in a fence perhaps, or a lamb separated from its mother. Eyes have to be on full alert – you don’t simply count the hens, lambs and pigs in the morning when you do your rounds, you are looking, always, for things that you don’t want to find, so you can intervene early and avoid more serious complaints caused by failing to notice problems. And get hands on: a thick fleece or heavy feathering can hide poor body condition or parasites. Know how heavy your hens should feel when you pick them up, and how prominent the spine is on a well fed or an underweight sheep.

In the first few years, absolutely everything is a new challenge, from how to put up a livestock-proof fence, to what to feed your ducks, what works best as bedding in your poultry huts, and how to grow vegetables when you have heavy clay soil. But with the basics sorted, and with growing experience and a keen mind, your learning moves on to more demanding issues – to more effective land management, dealing with health issues without constant recourse to the vet, and breeding.

Then there’s managing your plot for encouraging wildlife and native flora, rainwater harvesting, drainage, and possibly tractor and machinery use and maintenance. If you are scientifically minded you can explore carbon sequestration and soil health, do your own faecal egg counts and parasite analyses under a microscope, assess the impact of different grazing approaches on your land, and investigate the effect that minerals have on the soil and livestock. For those of a creative bent, working with fleece from the many and varied native breeds of sheep, or carving homegrown timber may satisfy the desire to make beautiful objects, and you will have endless subjects to inspire you if your interest lies in photography, painting or drawing.

You can develop the skills and understanding of an ecologist, environmentalist, nutritionist, agronomist and botanist. You can join schemes to monitor and maintain the health of your livestock, and the improvement of their conformation. If you are interested in showing your stock, that’s a whole other learning curve, and would satisfy the most competitive smallholder urge. You could learn about and follow organic principles, explore the pros and cons of raw milk consumption, or write children’s stories about a pet sheep named Curly.

Some smallholders become passionate about chickens – they keep many breeds, really understand the genetics behind feather colour, and can talk all things hen for hours on end – whereas I just want big, easy birds for delicious meat. Some smallholders have a passion for sheep and either keep one breed until they get as close to their idea of perfection as possible, or keep many different breeds to satisfy the urge for experimentation with fleeces or to provide a wonderful, varied view out of their bedroom window. As for me, I’m happy chatting about cows all day long. The point is that we all have our passions, and if you choose smallholding as a way of life you will have plenty of potential interests to enthuse about in the best possible way.

However, do avoid the known danger of acquiring something of everything and failing to acquire the knowledge you need to keep it all in good heart. It’s also worth saying that for the many who successfully take on a couple of weaners to rear for pork and bacon, additional knowledge is required to breed a sow to produce your own piglets: don’t underestimate the difference between rearing and breeding livestock. In particular, knowing what you’re going to do with the resulting livestock or meat needs planning.

The experience you gain over time may all be directed towards the improvement of your smallholding practices, or it might be tangential, using the plant and animal life as inspiration for other pastimes. What I can tell you is that there’s much to learn, much to enjoy, and much to hold your interest over a long lifetime.

More than anything, a ‘can-do’ attitude will get you through many demanding tasks, and the resulting sense of achievement is unassailable. In the winter our cows are housed for five months and we muck them out every single day, which becomes tiring by the time spring turnout approaches – and yet I still close the cowshed gate and turn to watch them munch on their haylage and smile at the clean concrete and freshly fluffed straw bedding with pleasure.

DEFINITIONS OF A SMALLHOLDING

Definitions of what a smallholding is range from the simple ‘a small farm’ to the equally vague ‘an area of land that is used for farming but is much smaller than a typical farm’, to the strangely specific, if out of date ‘land acquired by a council that exceeds one acre and either does not exceed fifty acres or is of an annual value not exceeding fifty pounds’ (at 1933 prices). A smallholding may simply be a patch of land where something agriculturally productive is happening.

Smallholders have to put up with many labels, some of which aren’t always applied entirely kindly. Hobby farmer is one such term, intimating someone playing at having a few animals and, it’s inferred, really making an amateurish hash of things. And then there’s the patronising ‘good-lifer’, as if the smallholder is shrugging off the benefits of modern life and living on dandelion wine, kale and scrawny chickens. I have far more respect for smallholders than those terms imply, and define smallholding in a number of ways – but the main principle is using whatever means and resources you have available to you to produce a quantity of your own food. That may be more than growing a few herbs in a window box or a dozen radishes and a row of lettuces in the back garden, or perhaps not.

And who is to say that this food production should involve animals of any sort? You may be growing an orchard that provides you with fruit and nuts, and cider and vinegar, and wine and fabulous puddings, or a vegetable garden that focuses on luxury vegetables such as salad potatoes, asparagus, artichokes, chillies, aubergines and crisp, fresh sweetcorn, and a fruit cage with blueberries, whitecurrants and autumn raspberries. Or you may have a pragmatic vegetable patch where your harvest of spuds, carrots, onions, peas and brassicas feeds the family all year round.

Home-grown breakfast.

An interest in food and food production is a critical element of smallholding – growing or rearing food for its superior flavour, nurtured for its eating quality and not jammed full of chemicals. The driving force behind many smallholders is to put great quality food of known provenance on the table, and there is no better provenance than home grown. There is also the element of producing many different things, for who wants to eat the same meal every day of the year?

Does smallholding require access to land? I’d say yes, but this could be a vigorously used allotment or a community-owned plot: who is to say that land sharing rather than personal ownership makes you a real smallholder? Not me. And I’ve known plenty of smallholders who have been more productive in a large suburban garden than those with a 5-acre pony paddock.

Does Size Matter?

Size does matter. Not that you aren’t a proper smallholder unless you have x amount of land, but because you have to take into account the scale of what you have to work with when making choices about what you will do with your space. You can’t put six cows, twelve goats and ten sheep on a single acre of land – well, you could, but it would be the most unholy mess of disease, and worse.

FROM SUBSISTENCE FARMING TO LIFESTYLE CHOICE

Subsistence farming is the growing and rearing of enough food to feed your own family to avoid starvation, with, if you are lucky, a small cash-crop surplus to trade for other goods. Although it may not be common in the developed world these days, sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South America have many subsistence farmers. There are about 500 million small farms in developing countries, supporting almost two billion people – one-third of humanity. Agriculture on the micro scale has existed almost as long as humans (certainly from 8500BCE), and there have been dramatic developments over time in how the world farms.

But looking at smallholding in particular there has been a noticeable evolution in recent times regarding what it means to be a smallholder. We have moved from the necessity of subsistence farming in order to stay alive, to widening our dietary options on a tight budget, to making a lifestyle choice to be more self-sufficient, and yet further, to rearing livestock as desirable pets for those with no budgetary constraints.

It may seem strange that a peasant life has become a desirable model for those with shallow or deep pockets, but nature, seasonality, fresh food and clean air are fundamental to our wellbeing, and smallholding offers that day in, day out.

Biophilia

Humans are innately attracted to the natural world. Even the most urban soul enjoys a stroll through the park, and for many, being in the open air, away from high rise buildings and the constant roar of traffic, is an essential part of maintaining a healthy mind and body. Smallholding takes the weekly hike through the nearest slice of green belt and the Saturday stint at the allotment into another realm of commitment. In exchange, your biophilia will be well catered for.

Giving Life Focus

We live in challenging times in a world being depleted, ravaged and disrespected. Contemplating this can be overwhelming at times, and although there are many things that an individual can do, there is so much that is also out of our specific control. Smallholding can give life a positive focus, concentrating on the things we can do and grow and create that improves things for those around us, including livestock and wildlife, and for the elements that surround us: water, soil and air.

This book isn’t a diatribe against the huge corporations that spend billions trying to convince us that laboratory-produced ‘food’ is better for us and our planet (I prefer to apply myself to what I can change, and others are better qualified than I to do the articulate railing against greed that’s needed) – but I know for certain that our home-grown 100 per cent pasture-fed beef and lamb is not the problem that needs tackling, and is in fact part of the solution. You may find that a smallholding life gives solace, and a sense that you can control your small slice of the world.

Way of Life or Lifestyle?

Only you (and your bank account) can decide if smallholding will be a full-time occupation, a focus for a busy retirement, a wonderful way to spend your weekends and evenings, or shared with other part-time working or as an element of a portfolio career. The sale of a moderate city house can still buy a place in the country with accompanying land, and often the land is an important part of the equation. In some cases, the realisation comes later that something needs to be done with the newly acquired acreage, and so a spate of accidental smallholding starts, and sometimes flourishes, sometimes not.

Hobby or Business?

What about the commercial aspect? Do you need to sell surplus sausages or eggs to friends and neighbours to be a smallholder? No. Do you need to make an income from other activities to be a smallholder? That will be dictated by your financial situation and life plan. If your smallholding is a business, does that stop you being described as a smallholder? No, of course not – making a financial success of this way of life is something many aim for and few attain.

Self-Sufficiency, or a Contribution to the Table?

A contribution to the table is what most smallholders strive for, whether that be focused on creating the full regalia of the Christmas dinner and perhaps a hog roast for friends in the summer, to producing the vast majority of everything that finds its way on to our plate. It’s such a personal thing, wrapped up as it is in acreage, time, interests and personal drive.

Produce stall with honesty box.

We produce all our own beef, lamb, hogget, mutton, pork, bacon, sausages, gammon, duck, goose, goat, eggs, much of our chicken, apple juice, cider, blackberry and cider vinegars, chillies, and a vast array of veg in season plus orchard fruits – and away from the table we produce all our firewood, harvest rainwater, and get electricity from the sun. We don’t produce our own milk or honey or cheese (cheese is my retirement plan). We make heaps of jam, chutneys and relishes, because we love and use them. I don’t knit or sew my own clothes, although I used to do lots of both. Have a go at many things, and stay with those that give you pleasure or are necessities.

Pets or Livestock?

What about people keeping livestock as pets? Does having a few graceful grazing alpacas make you a smallholder, or only if you keep them to see unwanted foxes off your poultry and lambs? Is a mini private petting zoo a smallholding? Things get a little blurry here, there being no food production element involved. If your animal keeping is more akin to having a couple of ponies, perhaps you don’t see yourself as a smallholder at all. However, an increasingly popular activity is the rearing for sale and keeping of livestock as pets.

This is a far cry from the original smallholding ethos, where everything produced was for consumption, by the producer or their customer. This is an indicator of a moneyed society, where some can indulge in statement livestock that enhance the look and feel of a country home. In the past this role was carried out by peacocks and herds of deer, but pet pigs, camelids, sheep, cattle, wallabies and emus now show themselves off in pastures that are put to no use other than fun, pleasure and rescue.

Part of the drive for livestock as pets is an innate desire to get back to nature and be closer to the land, even if taking the animals off to the abattoir is a step too far. Of course, the care of such creatures is no less demanding than those raised for meat.

Forever Popular

Taking back a significant degree of control over your own life is a huge comfort in uncertain times: when things are tough you might not be able to buy a pair of new shoes, but there’s always meat in the freezer, and veg and fruit in the garden. Creating a better life for family and children, with a wider appreciation of the natural world, plays a strong part in stimulating the smallholder.

OUR STORY

We all come to smallholding in different ways, and ours was accidental. In our early twenties and looking for a first home together without housemates, we came across a small converted dairy attached to a farm and riding school. We took one look at the tiny dark rooms with a bedroom in the eaves and ancient woodburning range, and said yes. The farmer renting out the place looked doubtful, as the last folk from London had lasted a week – but seven years later we had to wrench ourselves away. We got involved in pretty much everything on the farm: we got a horse, milked goats and cows, sheared sheep, built stables, created a veg garden, foraged for blackberries and field mushrooms, helped with fencing, made hay and the best friends ever.

The cob barn before.

The cob barn after.

Eventually we bought our own smallholding – a farmworker’s cottage with 3 acres that included a small barn, workshop, mature orchard, a stream for ducks and geese and a field. Wielding the slash hook, we unearthed and then restored duck huts, a chicken coop and run. Then we put up a greenhouse, created a big veg garden, and bought our first pigs and sheep.

A few weeks after arriving we watched a neighbour drive up and down their 3 acres on a sit-down mower, stopped to chat and asked if he enjoyed doing that. He didn’t, and we took over his acreage as sheep pasture in exchange for a lamb carcase each year – possibly the cheapest rental ever. We kept guinea fowl, chickens, geese and ducks, and were adopted by a stray peahen who left in a grump when we got her a peacock mate. After a ghastly dog attack on our sheep we bought a llama, which kept foxes and dogs at bay.

We ran the smallholding alongside demanding jobs. Andrew spent quite some time working abroad, and working in the arts I frequently worked evenings as well as the usual working week. We had to be very well organised and have fences that kept everything safely in and predators out, and took our holidays at lambing. In many ways it was the idyllic set-up, but we had energy to spare and wanted a bigger challenge, and ten years on started hunting for a 20- or 30-acre property. A quiet environment was absolutely top requirement, and we eventually found a small farm in West Devon with thirteen tumble-down buildings, dubious fencing, run-through hedges and over a hundred acres – but the house was in a decent if basic state of repair, and the location wonderful.

Our farmer friends took one look and went quiet, but by then we’d exchanged contracts and somehow weren’t fazed. We thought it would be a twenty-five-year project, but the majority of the work was achieved in less than ten. To start with we used 14 acres and rented out the rest to a wonderful farming family who have become great friends and mentors, and took back more land over time as our smallholding ambitions grew.

With twenty years of experience behind us, in 2009 we started to run smallholding courses of the kind we wished we’d had access to in the beginning. They have been phenomenally successful, and the people we meet come from all over the world; it has given us a great deal of joy sharing our learning, and hearing what next steps people take in their smallholding journey. With well over thirty years of smallholding experience, this book is a bringing together of the information we share on our courses, and a great deal more.

Reality Check

This book is fairly chunky, but it would have extended to fifty volumes if it included every smallholder possibility. Continue to enhance your knowledge, seeking out specific areas of interest, from home butchery to beekeeping, salami making to living off-grid. Smallholding can be a lifelong journey of acquiring information and skills.

2 Preparing for the Smallholding Life

Not everyone has to move house – or can afford to – in order to become a smallholder. You may have a garden big enough to keep a few hens, a trio of ducks, some rabbits, a few fruit bushes, window boxes of herbs and a veg patch. Or perhaps there’s a neighbour with a large garden that’s rather neglected that you could use in exchange for some fresh produce, or an allotment with your name on it. None of these options disrupts your life, and any one of them is practical, inexpensive and rewarding. But if your ambitions are broader, or your current situation provides minimal opportunities for testing out the smallholder existence, there are other ways to try before you buy into the whole smallholder way of life.

Smallholding course participants.

Why bother? Why not just jump into it with glee? In reality, moving home is an expensive process, and you may have to move to a completely new location to pursue your dream, with the loss of friends, neighbours, facilities, schools and employment opportunities that this entails. I estimate that more than 95 per cent of people who come on our smallholding courses are keen to get going, and after a couple of days they want to bring their plans forwards if at all possible and make a start. But a small yet noteworthy number of participants come up to me at the end of a course and thank us profusely, and say that although they’ve had a great time, they now know absolutely that it’s not the life for them (they hadn’t realised it was such hard work, that they would be responsible for doing this or that task, or that it was really not a good idea just to buy a few sheep, leave them in a field and let them get on with it).

TRY BEFORE YOU BUY

Trying before you buy is all about taking a reality check and looking at things sensibly. Even a day or two of experience or training can be enough to convince you that either this is truly your dream existence, or that there is absolutely no chance whatsoever of having, say, pigs, or even living in a rural location. Save yourself the grief and expense of an inappropriate purchase by first finding out what it involves – and you don’t need to throw in your job and volunteer with a smallholder in an inaccessible part of the country to get a good feel for it.

The first step, which won’t even get you out of your armchair, is to read a book or two. There are plenty around (see the appendices for recommendations), from in-depth studies of a specific topic (goats, lambing, bees or permaculture, for example) to lifestyle tales that depict a year in the life of a smallholder, and broader, comprehensive works such as this one that give you enough information to really understand what’s involved. Then there’s the world of free on-line videos, sharing skills such as artificially inseminating a pig to clipping a hen’s wing, with accounts that range from hilarious, to fascinatingly informative, to terrifyingly unsafe or inappropriate.

Increasing numbers of holiday cottages offer some smallholder experience: collecting the eggs, bottle feeding lambs, mucking out the pigs and so on, all of which can be an enjoyable way of getting the whole family involved in a light-hearted manner with minimum responsibility attached. You might have a local smallholder who would love a friendly hand from time to time, or you could volunteer at a city farm. With a stretch of free time, you could try one of the farm volunteer programmes, such as HelpX, Wwoof, WorkAway or Volunteers Base, which have farm and smallholding hosts all over the world.

For a day or two of focused training there are a number of smallholding courses around the country, including our own. Make sure that what’s on offer suits what you need, and that the trainers have plenty of experience in both delivering training and running a smallholding – it was attending a truly appalling training day that encouraged us to create courses we thought would be of real value to participants.

PUTTING NEW SKILLS INTO PRACTICE

You could read every book on the subject and go on all the courses on offer, but with some sense of the realities now in place, ultimately there will be nothing as nerve-rackingly rewarding as putting those new skills into practice and learning on the job. For example, it’s incredibly useful (actually, it’s probably essential) to be shown how to handle a sheep, and to tackle some yourself under supervision – but the practice you’ll get by dealing with your own flock will build on that learning and develop your skill to a level where you become confident in your own abilities – and there are no shortcuts for that.

I do want to raise a warning flag about the advice given so freely on social media. There are some extremely knowledgeable people on these platforms happy to share information and to respond to questions from the worried new smallholder. The trouble as a learner is knowing the difference between the good stuff and some of the awful suggestions made, which if followed could cause damage, or worse, to the land or animals under discussion. Even the most experienced can give poor guidance because they are swept away by the immediacy of social media interactions – so don’t, for example, ask Facebook for the dosage of certain medications or their withdrawal period, or what home remedies are cheaper than the medication that has been prescribed for your poorly pig by your (expert) vet.

MAKING FRIENDS

There are several regional smallholder associations, so do consider joining your local one. Getting to know more experienced smallholders gives you friendly contacts whom you can chat to, and ask questions about matters that you haven’t been able to resolve, such as where to get hold of a few wooden pallets, where to buy small hay bales, the best source for fencing stakes, which local large animal vets can be recommended in the area, or why certain poultry houses are more practical than others.

Cockerels and hens.

3 Land and Accommodation

I am in no way spiritual, with no religion or paganist understanding of the equinox, the mysteries of the moon, or the superstitions that surround the hawthorn and the holly. But, like probably every human that has ever been, I still find huge solace in nature. The whoosh of the sparrowhawk and the subsequent exiting flurry of blue tits and sparrows, the bursting forth of lime-green oak filigree in spring, the glistening clumps of frogspawn spattered with promise in the field ditches, are all rich with relief and reassurance that the world is turning as it should.

A DUTY OF CARE

The life of the smallholder is full of these moments if you just stand still and absorb them. Smallholders actively work with the seasons, not against them, and we have opportunities to enhance rather than damage the earth, and to enjoy what it offers. This is a daily privilege and explains why the smallholder life never fails to attract new blood. The land that we choose to work on, the land that beguiles us into its embrace, is our most precious resource: we can decide how to work with it and enhance it, or we can denude it, and although it is mightily forgiving, we have a duty of care to the land we stand on and all that lives on and in it.

CHOOSING A LOCATION

‘But where should my smallholding be?’ we ask ourselves, as if there were one perfect map reference destined for each of us. Luckily there is no single smallholding holy grail waiting for you to unearth it. Instead there is a range of things you should consider, from the must-haves to the ideals, and that list will be different for each of us. Just like any property, if you are contemplating moving to a new location, you might need to consider suitable access to employment and schools, but there are additional things to take into account when hunting for a home, which are as much about the patch of land as about the number of bedrooms.

Budget Constraints

Your biggest constraint is likely to be budget; children can change schools and adults seek new employment, and being flexible about location has an impact on what your money can buy. But be careful what you wish for. Moving to the Scottish Highlands for an affordable croft in glorious surroundings will be the answer to the prayers of some, but not all, so ask yourself the hard questions and be honest about your emotions, and your physical abilities and limits. For example, are you happy to be snowed in for weeks of the year, not seeing another soul and being forced to drag feed daily to your livestock on a cobbled-together sled? Will it worry you that friends and family are only prepared to visit in the summer, when you are at your busiest and most productive? Will the fact that it’s 10 miles to the nearest shop and petrol station put you off buying, also that the abattoir is six hours drive away, and there is no plumber willing to come out so you have to learn the trade yourself?

It is impossible to give a figure for the budget you’ll need. You’ll have to work out what you can afford to spend, and finance monthly. Researching what’s available and at what price will start to build a picture of costs in various locations. In some areas places with land rarely come on the market, and when they do they are extremely pricey, so don’t waste your time yearning for the impossible. The further you get away from cities the more options there are, but if your income relies on city-based working your attitude to commuting is a crucial consideration. Home-based working is growing all the time, even in sectors that previously thought this was an impossibility, and this is seriously beneficial to the smallholder who wants or needs to continue their existing employment.

Gateway beauty.

In 2022 the cost of agricultural land in the UK ranged between £7,500 and £10,000 per acre. However, if you buy a property and hope to purchase some adjoining land separately, that cost is likely to be multiplied many times; if it’s the perfect plot for you, the seller can ask whatever they like.

Quality of the Land

You don’t need Grade 1 agricultural land (of excellent quality for growing the most challenging crops such as salads, fruit and vegetables, at high yields) if you want to keep a few hens and sheep. Grade 5 permanent pasture (of very poor quality suited to grazing) would do fine, and you can always create raised beds to enhance veg growing prospects. If a market garden or edible flower enterprise is your intention, you’ll need to be fussier about the soil quality than if your ambition is a herd of goats. Trying to plant acres of fruit and veg on stony ground is not good either for your temper, tools or cropping rates. Having heavy clay means we resign ourselves to overwintering cattle in sheds for five months of the year; if this is something you don’t want to do (and who could blame you – it’s a lot of work), look for land that is free draining in areas with low rainfall, consists of limestone pavement, sandy soils or is heavy on the granite.

Appreciating the slope of the land and which way it faces will affect its productivity, for the same reason that everyone hopes for a south-facing garden to capture the most sun. If the plot is many metres above sea-level in the beautiful uplands, your surroundings will be glorious but the climate and terrain can be harsh, and you, your livestock and your crops need to be tough.

The acidity or alkalinity of the soil will affect what you can grow and how you manage your land, but an acid soil that is not rich in the rye grass much loved by commercial farmers may provide an abundance of wildflowers and other grazeable plants.

Rainfall, Water, Drainage and Sewerage

It is not difficult to research the typical annual rainfall of any particular area, although things do seem to be shifting from past norms quite quickly as we deal with the effects of climate change. Our patch of Devon is green and lush precisely because of the heavy rainfall, so just because your favourite holiday spot is gloriously sunny in August and requires nothing more than flipflops, shorts and a vest doesn’t mean you won’t have to invest in waterproofs and waders if you live there year-round. As obvious as the impact of heavy rainfall sounds, I’ve lost count of the number of people who move to the South-West, Cumbria, Wales or the west coast of Scotland without research, and are then surprised by the amount of rain they have to deal with.

Water supply is critical for a smallholder; expect water to be metered unless it is spring fed or comes from a bore hole, but whatever the supply, do ask about its quirks and any limitations before you buy. Boggy patches of land may be marvellous encouragers of wildlife, or simply a result of damaged and neglected drainage, and may scare you off unnecessarily. Resurrecting land suffering from broken drainage systems by replacing pipes choked solid with roots or crumbled by age and decay has a startling effect, turning ground previously impassable during wet seasons into good grazing. The same is true of clearing out ditches that have been trampled into non-existence by livestock over the years.

As for sewerage, we’ve lived for years with a septic tank and it has been no trouble at all; I think we’ve had it emptied three times in seventeen years. So don’t worry if you don’t have mains sewerage, and you will benefit from lower water bills.

PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY

If there are public rights of way such as footpaths or bridleways across the land you are considering purchasing, be clear what impact this may have on your smallholding.

You must avoid putting obstructions on or across the route.

You must make sure vegetation does not encroach on to the route from the sides or above.

You must not cultivate (plough) footpaths or bridleways that follow a field edge. The minimum width you need to keep undisturbed is 1.5m for a field-edge footpath and 3m for a field-edge bridleway.

You must avoid cultivating a cross-field footpath or bridleway. If you have to cultivate, make sure the footpath or bridleway:

ο remains apparent on the ground to at least the minimum width of 1m for a footpath or 2m for a bridleway, and is not obstructed by crops

ο is restored to at least the minimum width so that it is reasonably convenient to use within fourteen days of first being cultivated for that crop

Where a stile or gate on a public right of way is your responsibility, you must maintain it so it is safe and reasonably easy to use.

You must not put dairy bulls over the age of ten months in fields containing a public right of way. Bulls over ten months of any other breed must be accompanied by cows or heifers when in fields with public access. Warning notices relating to a bull should only be displayed when it is actually present in a field.

Horses may be kept loose in fields crossed by public rights of way, as long as they are known to be not dangerous.

Passing Trade

If you are intending to sell surplus eggs, veg, fruit, honey, meat and more to the public, being tucked away in a forgotten hollow or up a mountain, or anywhere truly off the beaten track, is not ideal if passing trade is your main market. On the other hand, such a location may be the perfect draw for campers and holidaymakers eager to buy the ingredients for a breakfast fry-up.

HOW MUCH LAND DOES A SMALLHOLDER NEED?

If your dream of smallholding is having enough space for a few ducks and hens, a couple of dairy goats, a vegetable garden and a small orchard, an acre may be quite adequate. But if keeping a herd of cattle is the key driver for your smallholding, realising this ambition clearly won’t be possible on an acre, so size really will matter.

The quality of the sward has an impact on the amount of acreage you need; living in the Midlands we could keep twice as many sheep to the acre as we now can in Devon, the grass coverage being thicker and denser and more productive.

If you are fit and not as ancient as me, you may wish to start small but have room to expand as you become more experienced and intrepid. Moving home is such an expense that you may be better off stretching your finances initially (still within a manageable range, of course – too large a financial burden can upset all your plans) to allow you to develop your interests over the long term.

The chocolate-box cottage with a 5-acre paddock is probably one of the most expensive and most desired property options. Instead, consider something that has more land than you think you’ll ever need, and a house that may not be prettily swathed in wisteria and yellow roses. Land that is surplus to your initial requirements can earn you an income until you are ready to put it to use by renting it out.

There are as many different designs of smallholding as there are smallholders, but the diagrams overleaf give you a sense of the possibilities on varying sizes of plot. But don’t be fooled into thinking these concepts are definitive – you don’t have to mimic these ideas to be a ‘real’ smallholder. Make your own plans, create your own dreams, mix it up and do the things that make you happy.

ACRES AND HECTARES

Land size is as often given in acres as it is in hectares. An acre is 70 × 70yd, or 63.5 × 63.5m (4,047sq m). A hectare is 10,000sq m (100 × 100m) and equates to 2.47 acres. To visualise an acre, a football pitch is about 1.5 acres, and if you include the ground usually surrounding the pitch in a stadium, it is closer to 2 acres in total.

WHAT MIGHT YOU ACHIEVE ON YOUR ACREAGE?

What you can achieve on your acreage of course depends on whether it is made up of rock, bog, woodland or thickly covered pasture, and what your particular ambitions are. For example, you may wish to dedicate all your space to breeding alpacas for their fibre, and I haven’t accounted for that.

Possible Activities on a Certain Acreage

AcreagePotential activitiesHalf an acreAt this size you can have a highly productive vegetable and fruit garden, a handful of chickens and ducks, bees, meat rabbits and quail. Hedges can provide foraging opportunities.One acreWith an additional half acre, you can have the above plus a couple of weaners to raise for pork, and a couple of lambs to raise for meat, or a few geese. With a smaller veg area and plenty of hedges to cut for browse, you could keep a couple of milking goats instead.Five acresThis size gives you plenty of options. You can add into the mix an orchard, geese, and a small flock of breeding sheep. Dairy (or fibre) and meat goats are possible, or you could keep a couple of cows. There might be woodland for firewood, and enough space for a breeding sow or two. Laying up some grass to make hay is possible. But you can’t do all these at the same time.Ten acresWith 10 acres you can have all of the above, rather than picking and choosing. You can produce enough hay to feed your livestock over winter. Your grass management options improve, allowing areas to rest and regenerate, and you can initiate new projects over time (a vineyard or cider orchard perhaps).Fifty acresThis size constitutes a small farm: you can have larger numbers of livestock of all kinds, and can produce arable crops for feed and bedding if desired and if land quality and access to suitable equipment allows.It is critical not to overstock your acreage with livestock, as this will be to the detriment of both the animals and the soil. See the later section for indicative stocking rates.

One acre.

The author’s first smallholding (3.25 acres)

Ten acres.

STARTING FROM SCRATCH OR READY-MADE?

Finding a ready-made smallholding that fits your precise dream list is unlikely – and anyway, having an overlong list of ‘must-haves’ may mean losing out on the property that ‘might have been perfect if only I hadn’t been obsessed by the inadequate galley kitchen’. Having initially discarded a property precisely because the kitchen was tiny and incredibly dark, I drove past a few weeks later and realised what promise the whole package actually had – and soon after it became our first smallholding. A few years on we knocked the kitchen through to the dining room that we never used – and the house went from ugly duckling to swan.

The deluge of property programmes on television serves to highlight how a single-minded hunt for a place with the perfect this or that is likely to end in disappointment, and how compromise has to be squarely embraced. The one thing you can’t change is the location, so focus on potential, rather than fretting over the elements you can improve over time. See an avocado bathroom suite and a crumbling pigsty as projects, not insurmountable defects. When we moved to Devon the farm was in a truly dreadful state, but a decade on, and the main failings had been addressed. We have usable barns with roofs and walls, the land is fenced, the hedges, ditches, drains and woodland restored. The situation of the farm, down a lane with grass growing in the middle of the road, surrounded by its own land, offered space, quiet, air to breathe, and a life seated in natural beauty.

Derelict cowshed.

Restored cowshed.

The house-related things I’d find challenging to live without include peace and quiet; an outside or easily accessed downstairs toilet; a utility space for boots, wet weather gear, livestock medication, washing machine and dogs; a kitchen that’s more than a cubby hole; an office space; broadband; a sofa to snooze on; a shower and a comfortable bed. And that’s pretty much it.

PLANS FOR YOUR SMALLHOLDING

People who are really clear about the shape of their smallholding ambitions are quite rare; most have a fancy for a few chickens, perhaps a couple of pigs, a veg plot and a few goats or sheep if the land allows, but are open to other possibilities. Unless you have absolute requirements (a vegetable garden that feeds the whole family year-round, which might dictate that living on a rocky mountain is not going to work), you may be happy to let the chosen holding shape your next steps. You may not be particular about whether to keep sheep or goats, and a holding with a lot of scrub and browse may direct you more towards goats. An exposed plot by the coast may mean that a plum orchard is not going to be practical, but you can grow a sheltering hedge and have a few dwarf fruit trees against the south side of the house. The plot shapes your ambitions and generates ideas, and there isn’t time or inclination to fret about the limitations.

Jersey house cow and calf next to a pig paddock.

If you do have very specific plans, make sure the place you choose can accommodate them. It sounds absurdly obvious to say that, but the attractiveness of a holding can grasp you firmly by the heart. In the excitement of finding an inspiring new home it is possible to forget that your primary aim was to have cows and a micro dairy to explore a future as a small-scale cheesemaker, and overlook the truth that the land is entirely unsuited to the few Jersey milkers that have populated your dreams.

Outbuildings, Sheds, Barns, Lean-Tos and Shelters

The smallholder who doesn’t have any sort of outbuilding faces a serious challenge – and to be frank, the more you have, the more helpful it is. If you take on somewhere with clusters of old buildings, please don’t spend the first year razing them to the ground. Once you start smallholding, you’ll probably want to use any and every building’s footprint and possibly its structure to repair, rebuild and restore. Flattening everything and starting from scratch may cause planning headaches, and on a practical note, if previous owners have been canny, the siting of old buildings is usually the best location for them in terms of drainage, access, prevailing winds and ease of movement from place to place. There are exceptions, of course, where the siting of an ugly building in front of the kitchen window may be an affront to aesthetics and practicality.

You’ll need somewhere dry to store hay, straw, animal feed and equipment. You might want a small dairying space; all goats will need a shelter, and like us you may prefer to lamb, kid, calve and farrow inside. A space to quarantine poorly animals is useful, or having a shed with adequate human headroom to house your poultry (this is a boon when mucking out, and also when overwintering poultry inside because of the increasing likelihood of seasonal avian flu lockdowns). A simple workshop where repairs can be done and tools kept is all but a necessity, plus somewhere to store your produce, whether in freezers, jars or loose on shelves.

If you plan to build a barn, space allowing, make it bigger than you think you’ll need. And don’t butt it up against a corner boundary, because in a few years you may be grateful that you can add on lean-tos to more than one side.

Stocking Rates

Every smallholder wants to know what numbers of livestock a plot of land can sustain. The answer is dependent on many factors, including the sizes and breeds of the animals you plan to keep, the quality of the land, whether you expect to make your own forage, and whether you feed concentrates or not. Suggestions are given in the table below, and they are deliberately generous on land allowances, ranging from larger to smaller breeds, and assuming that you buy in forage for the winter months and are therefore not using any of that land to make hay.

Always underestimate stocking rates; you can add to your numbers if the land proves more productive than you anticipate, and if you have breeding animals, numbers will quickly increase. And remember that you can’t have all of these options per acre: if you have 1 acre and five ewes and lambs, that’s your allocation completely used up.

Stocking Rates

Species

Numbers per Acre

Chickens

50–100

Ducks

24–40 large breed ducks

Geese

8–16 adults

Sheep

3–5 ewes and their lambs

Goats

2–3 goats and their kids

Pigs

3–4 sows with litters24 weaners (7–18kg per weaner)11 growers (18–35kg per grower)7 porkers/baconers (35–90kg)

Cattle

<0.5 cow (2 acres for a cow and its calf)

TIDYING UP NATURE

There are plenty of places for tidiness on a smallholding: the neat heap of holding registers, the veterinary medicine book and the folder for movement licences; the bucket of baler twine ready for use; the garden tools hung from hooks; the well stacked bales of straw and hay. But please avoid being an inveterate tidier of nature. In our courses we are asked all the time how ancient ridge and furrow land can be flattened, how hillocks can be smoothed away, how nettle patches in an untended corner can be removed forever, or how a stream can be straightened.

Don’t be too tidy.

The answer is to leave well alone, or even to encourage nature to make it messier yet. Let gorse and brambles spill through your fencing; they will create a much enjoyed larder for yourself and wildlife, and will stop livestock pushing against the fence. Allow what you might consider weeds to flourish as hosts to insects where they don’t interfere with you. Don’t spend your life on a sit-down mower removing every wildflower or broad-leaf plant – this is a smallholding, not a bowling green. If you must tidy, save it for marshalling your chutneys in lines on their shelves, keeping your wheelbarrows in rows, or parking any tractor implements in a satisfactorily neat formation.

This isn’t to say that every tree, shrub, copse and rill should be left as it is. Drainage ditches need maintaining, ponds can be created, hedges benefit from trimming and laying just as roses do from pruning, new trees and hedges should be planted, and sour land enlivened. There is a lifetime of reading and study available to you on restorative agriculture, improving soil structure and biodiversity, regenerative grazing practices and sustainable livestock production. The principles apply equally to a 500-acre farm and a 3-acre smallholding. Pockets of unmown sward will be rich in insects that will encourage bats and birds, voles, slow worms and butterflies, and if you’re lucky your compost heap will contain grass snakes.

BUYING, RENTING, BORROWING, COMMUNITY SHARING AND TENANCIES

Although most smallholders hope to buy a smallholding – a patch of land and a house to live in – as one tidy package, this may not be possible. But there are other options, such as renting land not too far from home, or using land that another smallholder can no longer manage, for reasons of age, health, work or family demands. There are community land shares and a very few council tenancies, and you may find that housing and a piece of land is part of an employment opportunity.

Hunt out local allotments, talk to neighbours with garden to spare, or investigate small plots of land that are looking unloved and ask the owner if you can tend them (the Land Registry provides details on land ownership if asking locally fails to provide that information). I’ve had numerous conversations with determined cash-poor smallholders-to-be who have spoken to all the farmers and landowners in their vicinity, finally resulting in an agreement to use a piece of land. Many people rent a field at some distance from home in order to get started.

Agricultural Ties

An Agricultural Occupancy Condition (AOC), more commonly known as an agricultural tie, is a covenant placed on a property by the local authority restricting its occupancy to workers who are solely or mainly actively involved in agriculture as their main occupation. Ties are used by planning departments to stop people building houses claiming that they are needed to house an agricultural worker, and then selling them on the open market. It may be possible to have the tie lifted, but this is by no means assured.

To try to have the AOC removed the owner is required to put the property on the open market for anything up to two years at its genuine value, which is likely to be around 65–75 per cent of the value it would have without the AOC. If it can be shown that despite their efforts there are no buyers who meet the AOC criteria interested in purchasing with the AOC in place, the owner can apply to their local planning authority to have it lifted.

An alternative is to apply for a Certificate of Lawful Use (CLEUD), where the local planning authority certifies that an existing building use is lawful. It has to be proven that the people living in the property for at least ten years have already been in contravention of the AOC rules for that period.

HEART AND HEAD

You may have sensibly drawn up a checklist to guide your smallholding search, but if you are anything like me, you’ll stand at the entrance gate, blind to the ‘Danger, do not enter’ signs plastered over the barns, gaze at a long, whitewashed building with yellow doors and window frames, and say: ‘This is it!’ – and hopefully it will be.