Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

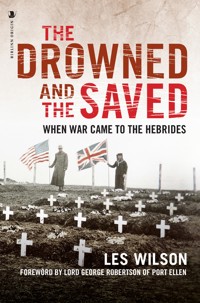

WINNER OF THE SALTIRE SOCIETY HISTORY BOOK OF THE YEAR Next morning at about 6 o'clock my mother wakened us to say there had been a shipwreck and bodies were being washed ashore. My father had gone with others to look for survivors ... I don't think any survivors came in at Port Ellen but bodies did. The loss of two British ships crammed with American soldiers bound for the trenches of the First World War brought the devastation of war directly to the shores of the Scottish island of Islay. The sinking of the troopship Tuscania by a German U-Boat on 5 February 1918 was the first major loss of US troops in in the war. Eight months after the people of Islay had buried more than 200 Tuscania dead, the armed merchant cruiser Otranto collided with another troopship during a terrible storm. Despite a valiant rescue attempt by HMS Mounsay, the Otranto drifted towards Islay, hit a reef, throwing 600 men into the water. Just 19 survived; the rest were drowned or crushed by the wreckage. Based on the harrowing personal recollection of survivors and rescuers, newspaper reports and original research, Les Wilson tells the story of these terrible events, painting a vivid picture which also pays tribute to the astonishing bravery of the islanders, who risked their lives pulling men from the sea, caring for survivors and burying the dead.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 375

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Drowned and the Saved

Les Wilson is a writer and an award-winning television documentary maker who has specialised in Scottish historical subjects. His work includes films about the ‘Lighthouse’ Stevenson family; engineer Thomas Telford; writer, adventurer and political activist Robert Cunninghame Graham; the principal chief of the Cherokee nation, John Ross; and the artist who created the monumental Kelpies sculptures, Andy Scott. He has made documentary series about Scotland during World War Two, and the history of the Scottish regiments. He lives on the island of Islay.

Also by Les Wilson:

Scotland’s War (with Seona Robertson), Mainstream, 1995

Fire in the Head, Vagabond Voices, 2010

Islay Voices (with Jenni Minto), Birlinn, 2016

THE DROWNED AND THE SAVED

When War Came to the Hebrides

Les Wilson

s

First published in 2018 by Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Les Wilson

The right of Les Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 027 8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

MBM Print SCS Limited, Glasgow

For Jenni

Contents

List of illustrations

List of maps

Foreword

Introduction

1 A Stroke in the Dark

2 The Grand Miscalculation

3 A Terrible Detonation

4 The Boiling Angry Sea

5 They Put Iron into Our Souls

6 I Heard the Siren Warnings

7 And There Was a Seaman!

8 A Gloom over the Whole of Islay

9 The Bivouac of the Dead

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Illustrations

Port nan Gallan on the Oa.

The Tuscania funeral procession passes through Port Charlotte.

The US flag and the Union Jack flying at Port Mor.

The salute is fired at Kilnaughton Cemetery.

The first Tuscania mass funeral at Kilnaughton.

American survivors of the Tuscania after the first funeral.

The Stars and Stripes carried at the Tuscania funerals.

David Roberts, survivor of the sinking of the Otranto.

Captain Davidson in his cabin on the Otranto.

Bodies of Otranto victims at Kilchoman churchyard.

The victims of the Otranto are re-buried in a second funeral.

American Red Cross workers deliver emergency supplies.

Lieutenant James Jeffers of the American Red Cross.

Survivors of the Otranto treat their rescuers to afternoon tea.

The American Monument on the Mull of Oa.

Maps

Islay

The Oa

The Rhinns of Islay

Foreword

Lord George Robertson of Port Ellen

Even for a Hebridean island used to some foul weather and occasional wrecked ships, the events of 1918 in Islay must have been especially grim. To experience one major troopship disaster that February was traumatic enough for a small island community already hit severely by casualties on the distant Western Front. But to face another disaster only a few months later was unprecedently awful.

Islay was not rich, it was agricultural and it was quiet. The great boom in Scotch whisky drinking had not yet stimulated the small island distilleries and tourism was in its infancy. To this peaceful rural community was to come a visitation of brutal violence and profound sadness.

The torpedoing of the liner Tuscania, carrying 2,000 troops, in February 1918 brought to the island both dead victims and survivors in huge numbers. It happened in the night, it happened on the remote and inhospitable cliffs and rocks of the Mull of Oa and it brought forth bravery, service, humanity and the resources of the islanders to a quite remarkable degree.

Two hundred soldiers and sailors died. It was the biggest loss of American military lives in a single day since their Civil War. When news hit the US, the shock was considerable.

When the troopship Otranto fell victim to a collision off the western rocky shores of Kilchoman in October of the same miserable year, the last of the so-called Great War, the previous experience was useful. But the double shock was to leave lasting legacies of pain and mourning. Another four hundred perished.

My maternal grandfather, Malcolm MacNeill, was the police sergeant on the island in 1918. With his three constables, he was in effect the public authority on Islay. Yet nothing in his training or experience could have prepared this son of a shepherd from Inverlussa on the neighbouring island of Jura for the challenges he faced on these grim days in the last months of the First World War.

Just a few years earlier, another police constable serving in Port Ellen, Norman Morrison, wrote in his autobiography:

The duties of a country constable on the whole are generally speaking, interesting and pleasant, particularly when one is stationed in a district which is free from crime. Routine work is easy and sometimes even fascinating. To the lover of the beautiful in nature, the life is really an ideal one.

Before patrol cars and an air service and the telecommunications we now take for granted, the scale of the difficulties Sergeant MacNeill faced was simply immense. He had to travel by bike in hellish weather to the remote extremities of the island. He had to organise the rescues, the handling of survivors, the recovery and cataloguing of the dead, the recording of events and the communications from and to the legion of top brass who eventually descended on the scenes of these disasters.

He was not alone in his endeavours, for the scale of the tragedy and its aftermath brought out the very best in a hardy, resilient and resourceful Islay population.

The American Red Cross, on the scene in the weeks after each event, was unsparing in its praise:

It is quite impossible to say too much of the humanity of these peasant people, of their readiness to accept any hardship in the name of mercy, of the gently, steadfast nursing they gave the soldiers, virtually bringing them back to life.

One might quibble with the word ‘peasant’, but the sentiment expressed speaks of what these American professionals found when they arrived on the scene.

My grandfather, known to me by the Gaelic word Seanair, bearing the enormous responsibilities of the day, was systematic and diligent in his efforts. His notebook, in copperplate handwriting, accounting for all the bodies, was found in a cupboard of his son Dr Hector MacNeill. It is now in the Museum of Islay Life, and is a remarkable chronicle of profound sadness; his descriptions of often unidentifiable battered corpses cannot leave any reader unaffected.

The reports he had to write each night after his travels (written twice so as to keep a copy) were to be followed by the painstaking follow-up letters to bereaved families. The interment of bodies, the organising of survivors, the identification of the islanders who had opened their homes and shared their food and clothing, the recording of the bravery and sacrifice that were shown – all fell to these few local members of Argyllshire Constabulary whose lives were changed forever.

He himself was – exceptionally for a country police officer – to be honoured after the war with one of the first medals from the newly created Order of the British Empire. That MBE, the property now of his great-grandson – another Malcolm MacNeill – is also on display in Islay’s Museum.

I was born in the Police Station in the Islay village of Port Ellen, my father having returned from Second World War service to take up duties as a policeman on the island where his father-in-law had been a police sergeant before him. I went from there, via a life in politics, to become Britain’s Secretary of State for Defence and then Secretary General of NATO, the world’s most successful military alliance. I saw conflict and witnessed how humanity deals with mass casualties. I am consequently filled with admiration at what my fellow islanders did at that time.

The stories in this book, collected brilliantly by Les Wilson, articulate the dramas of both disasters and show how a rural community rose to the immense challenges of tackling them. We see the kindness of islanders with so little, who gave so much. How they produced clothes and food for the survivors and tenderness and compassion for the dead. How coffins were made, graves dug, a Stars and Stripes made and sewed overnight by local women to ensure the fallen lay under their own flag.

When I made a BBC Scotland radio programme a few years ago about the two disasters, local Port Ellen fisherman and my friend, Jim McFarlane, related how he was told of people openly weeping in the streets as the carts with bodies passed. I also stood in the home in Kilchoman of Duncan McPhee, the grandson of one of the two teenage McPhees who waded into the surf when the Otranto went down, armed with a walking stick, to reach and save two men from certain drowning. As we remembered that act of heroism I recalled what my grandfather had recorded of that night: ‘The oldest inhabitants in the neighbourhood of the wreck say that they never saw a heavier sea on the Machrie Sands and very seldom a higher tide.’

But the Tuscania and Otranto and the lasting effect of their sinking are not forgotten on Islay. Rising tall above the sheer cliffs and rocks of the Mull of Oa and at the closest point to the sunken Tuscania is the mighty monument to those who died a century ago. The cemeteries at Kilchoman and Kilnaughton may have lost the American graves, almost all the bodies being solemnly repatriated to the US and to Brookwoods Cemetery near London, but British sailors still lie there. In Kilnaughton Cemetery, by Port Ellen, there remains the only American grave left on Islay. Roy Muncaster’s mother wanted him to stay where he died.

So many lives lost. So many lives saved. So many survivors looked after. A community rising to the tragic occasion, everyone pulling together to counter what fate had thrown at them. In many ways this is the story of a special island and its strong, resilient, resourceful people. Out of tragedy came inspiration, and out of misery and death came kindness, generosity and enduring humanity.

A century has passed but the memories live on.

Lord Robertson of Port Ellen, a native of Islay, was UK Defence Secretary and NATO Secretary General. A member of the House of Commons for twenty-one years, he was elevated to the House of Lords in 1999. He is one of the sixteen Knights of the Thistle, Scotland’s oldest and highest honour, and is Chancellor and Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George. He is one of only four UK citizens to hold the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest decoration and only rarely given to foreigners.

I hear those voices that will not be drowned.

Charles Montagu Slater,

Libretto for Peter Grimes by Benjamin Britten, 1945

Introduction

Driven against a rocky coast in a savage winter storm, David Roberts fought for his life. The deep-rooted human instinct for survival was on the side of this rookie American soldier, but nothing else was. He recalled: ‘A wave about as high as a house came over me and whirled me around like paper in a whirlwind.’

Roberts was exhausted, frozen and in danger that – at just seventeen – he could never have imagined, far less been trained for. If hypothermia didn’t kill him, the mountainous waves could plunge him underwater and hold him there until his lungs flooded with freezing brine. And there was the wreckage. Flung around by the wind and waves, an angry mass of shattered timber was pounding shipwrecked men against the rocks of the Hebridean island of Islay’s gnarled west coast. The experience has been likened, by the current coxswain of Islay’s lifeboat, to being thrust into a meat grinder. By some fluke, or miracle, young Roberts kept his head above water, without being crushed or knocked unconscious, and the crashing waves hurled him onto a rock, frozen, battered, half-drowned, but alive. Hands reached out to him. A boy, hardly older than Roberts himself, was hauling him to safety. Donald McPhee was risking his life. His younger brother, John, had to hold on to Donald’s belt to prevent him being swept out to sea as he dragged the young American ashore.

Roberts was one of nearly five hundred men who had been thrown into the water when a British ship, carrying American soldiers to the trenches of the Western Front, foundered off Islay after a catastrophic collision in a storm. Only twenty-one made it ashore alive, and two of them died shortly afterwards. In the days that followed, hundreds of drowned and battered bodies were washed ashore. The wreck of HMS Otranto was the greatest tragedy in the history of the convoys that took more than a million young American soldiers – doughboys – to the Great War in Europe.

Eight months earlier, Islay had seen another naval disaster off its coast, when the troop transport SS Tuscania – with more than 2,000 US soldiers and nearly 400 British crew aboard – had been torpedoed by a German U-boat. On a pitch-black February night, a relentless swell drove overcrowded lifeboats onto the island. Boats were smashed against the rugged shore, tumbling men into the sea. Many were rescued, but 126 bodies were washed ashore for the islanders to gather, attempt to identify, and bury with dignity amid an outpouring of grief.

The sinking of the Tuscania was a symbolically significant milestone in twentieth-century world history – the point when the isolationist USA began to shed blood in Old Europe’s wars. As the official history of the American Red Cross during World War One says: ‘The Tuscania’s dead represented, in a way, the first American casualties in the war . . . the sinking of the Tuscania was, as one might say, a special occasion, like a particular battle.’

In telling the story of the loss of the Tuscania and the Otranto, and of the Hebridean islanders who buried the drowned and tended the saved, I have, whenever possible, based the narrative on the words of people who were directly involved. These accounts come from letters, diaries, memoirs, speeches and interviews in newspapers, as well as from the records of official inquiries. Inevitably, inconsistencies occur. Even the number of men lost is not certain. It seems likely that 470 men died on the Otranto, 358 of them American soldiers, while the estimated losses of soldiers and crew on the Tuscania varies from 166 to ‘over 200’, 222, 245 and, according the National Tuscania Survivors’ Association, 266. There are also inconsistencies in the reported timescale of events. This is likely to be at least partly due to witnesses having their watches set to three different time zones – American, British and German.

For me, the meeting of David Roberts and the McPhee brothers on a storm-lashed shore – one tiny scene in a huge tragedy, acted out on the stage of Islay and the seas that surround her – is a profoundly moving symbol of humanity amid the terrible Great War. The people of Islay took total strangers into their midst and treated them as their own, tending the wounded, and burying the dead with honour and respect. In America, grieving families responded to that kindness. Beneath the stormclouds of war and tragedy, a sense of shared humanity was felt across the wide and stormy Atlantic Ocean.

Today, these century-old tragedies remain part of the warp and weft of Islay’s lore, tradition and life. Graves are tended. Relatives of the lost American soldiers and British sailors visit the island. Records are requested and examined in the Museum of Islay Life. Pilgrimages are made to the great monument to the American dead, which stands on the Islay peninsula called the Mull of Oa. Stories of the two ships are told, and passed on. Points on the landscape are recognised as being imbued with significance. The men and women who pulled exhausted, frozen survivors from the sea, and fed and comforted them, still have descendants living on the island. Islay’s volunteer Coastguards and Lifeboat crew of today are the spiritual and sometimes the blood-descendants of those whose bravery and kindness saved lives nearly a century ago.

The shockwaves from the Tuscania and Otranto disasters struck many an American community harshly, as men who had enlisted together died together. Of the 60 war dead commemorated on Berrien County’s World War One memorial in Nashville, Georgia, 25 were lost when the Otranto went down. The impact of World War One on Islay was also immense. The island – a community of then just over 6,000 people, scattered among small villages and isolated farms – lost more than 200 of its young men on foreign fields. But with the wreck of the Tuscania and Otranto, the devastation of war came, literally, to Islay’s shores.

If I had been living in my house in Port Charlotte ninety-nine years ago, I could have looked out of my kitchen window to watch the pipers lead the first Tuscania funeral cortège up Main Street to the freshly dug graves at the edge of the village. The land had been donated by the local Laird, the coffins made by carpenters at an Islay distillery, the carts that carried them were lent by farmers and tradesmen, and the procession of mourners was made up of local folk who did not know the victims, but cared for them nonetheless. They had been unable to bury Islay’s own war dead, who lay in France and beyond, but were determined to honour these fallen strangers and allies.

Earlier today I walked the fatal coast where Tuscania survivors fought for their lives as their lifeboats were driven against the rocky shores of Islay in the early hours of 6 February 1918. After more than a year of researching and writing, I needed to bring back into focus my motivation for writing this book. When I began it, I expected to confront tragedy aplenty, but what I had not been prepared for was to discover instances of incompetence and accusations of dereliction of duty on the part of British crewmen. They made hard reading, and so, before I wrote this introduction, I needed to remind myself of the countless instances of courage, endurance and humanity that appear in these pages.

I hiked out to the clifftop on the southern coast of Islay’s Oa peninsula and the massive monument that commemorates the American soldiers lost on both ships. I didn’t linger long. A south-south-easterly wind was blowing up and it had reached gale force and was gusting up to nearly 60 mph by the time I returned to the car. It was a reminder – if such was needed – of how wild and dangerous the coast of Islay can be. I had stood in the lee of the monument and watched the ferocious seascape. More than four hundred feet beneath me lay the rocks where – in the pre-dawn morning, 99 years ago to the day – Tuscania men died as their lifeboats were dashed ashore. Close by were the farmhouses where survivors were given sanctuary by kindly islanders. About fifteen miles to the northwest lay Kilchoman Bay, where nearly 500 Otranto men were thrown into the sea and where 19 lived because local people were kind and brave. Three thousand miles to the west of where I stood lay America.

The great and powerful Republic of America . . . and the little island of Islay. Two very different communities forever linked by events that were tragic, but which were shot through with heroism, fortitude, kindness and respect.

Les Wilson, Port Charlotte, Isle of Islay, 6 February, 2017

Islay

1

A Stroke in the Dark

It came on them like a strange plague, taking their sons away and then killing them, meaninglessly, randomly.

From Iain Crichton Smith, The Telegram

Islay lies on a bed of ancient rock, set amid often angry waters at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. Ireland is to the south, mainland Scotland to the east, and Newfoundland nearly 3,000 miles due west. Islay isn’t the biggest of the Hebrides, or the most populous, but its strategic position on the western seaboard of Scotland makes it stand out in the histories of immigration, emigration and war.

The islanders had already drunk deeply from the well of grief when tragedy washed up on their shores in February 1918. By the time the troopship Tuscania was torpedoed, 125 Islay men had already been killed in the war, and many hundreds more were still fighting on land and at sea. On an island of small and closely knit communities, not a family would have been untouched.

The pain of parting when men are called to war was captured by Islay bard Duncan Johnston, who served in the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders until he was gassed in 1916. His song about leaving a girl to go to war, Sine Bhàn (Fair Sheena), is still sung on Islay today. Such a theme could have moved a soldier to write in English, French, German or Russian, but Johnston wrote in his native Scots Gaelic. Here are just two stanzas:

Feumaidh mise triall gun dàil

Chi mi ’m bàrr a croinne sròl.

M’ ’eudail bhàn, o soraidh slàn!

Na caoin a luaidh, na sil na deòir!

Cha ghaoir-cath’ no toirm a’ chàs’

Dh’ fhàg mi’n dràsd’ fo gheilt is bròn

’S e na dh’fhàg mi air an tràigh,

Sìne Bhàn a rinn mo leòn.

Parting time is drawing nigh,

Flags are waving at masthead,

Darling child, O do not sigh!

Do not cry, my lovely maid!

It isn’t war or cannon’s roar

Unmans me now and makes me mourn,

My heart is left on yonder shore,

My lonesome lass; my sweet, forlorn.

Hebridean islanders were used to partings. Since the mid-eighteenth century there had been mass emigration from Highland Scotland, and names like New York, Philadelphia, Buffalo and Chicago tripped easily off the tongues of Islay folk who had kin there. By the outbreak of war in 1914, Islay’s history was already deeply entwined with that of the brave new republic across the ocean. But within four years the islanders had learned a fearful new geography – Mons, Ypres, Neuve Chapelle, Loos, the Somme, Gallipoli. Islay people had blood relations in these places – fighting in the trenches, or already in their graves.

Most of the fallen had worn the uniforms of famous Scottish regiments, including that of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, which has a long tradition of recruiting on Islay. Some islanders, who in peaceful times had sought to make new lives far from home, fell alongside Canadian and Australian comrades. Islay men also died simply following the peacetime calling of merchant seaman. Others, many of them fishermen, were killed while serving in the Royal Naval Reserve and the RNR Trawler Section – a fleet of commandeered fishing boats that had been converted to serve as minesweepers. Minesweeping was a dangerous job, and cost the lives of at least two Islay men.

Some of the bodies of Islay’s dead were never found, but most lie under plain, uniform headstones in foreign fields now maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. At home on Islay, friends and loved ones had been denied the farewell rites of funerals, or graves to visit and tend. But Islay was soon to be overwhelmed with funerals and graves. The losses of the Tuscania and the Otranto gave the war-weary islanders a purpose and a cause to unite behind. Soldiers and sailors who had survived the shipwrecks found safety, sustenance and kindness among the islanders. The dead found hearts that would grieve for them and willing hands to lay them to rest.

Islay is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides, lying between the Scottish mainland and Northern Ireland. At 240 square miles it is Scotland’s fifth biggest island. The mild climate favours agriculture and tourism, but winter gales are common. Even today Islay’s lifeline ferries to the mainland, with all their sophisticated navigation and stabilising equipment, cancel sailings in extreme weather.

Islay was, and remains, an island of scattered villages and farmhouses. Today it is home to just over 3,000 people, but the 1911 census shows that the pre-war population was twice that. About 80% of the islanders spoke Gaelic. The great majority of the people lived by farming, fishing and distilling whisky (for which the island is justifiably famous). Native islanders are called Ileachs, and their surnames appear again and again in Islay’s history, on its war memorials and on today’s electoral roll – Anderson, Campbell, Currie, Darroch, Ferguson, Gilchrist, Johnstone, MacArthur, MacDonald, MacDougall, McIndeor, MacLellan, MacMillan, McPhail, McPhee, MacTaggart . . . and many more.

Islay was remote. The first motor car didn’t arrive until 1914, there were no telephones, the first aeroplane didn’t land on Islay until 1928, and the island wasn’t connected to mainland electricity until 1965. But when war broke out in 1914 Islay enjoyed strong family and community ties that gave islanders a pride of place and a vigorous local culture.

Four years of conflict took its toll. By the dawn of 1918 Islay, like the rest of Britain, was sick of war. As well as the carnage inflicted on soldiers and sailors, civilians were suffering from shortages, rationing, rising prices and taxes, and were in constant dread of the ‘deepest sympathy’ telegram. A letter from the spring of that year, now in the Museum of Islay Life, reveals something of how the island was being affected. In it, Robert Smith of Laggan Farm brings his friend, Andrew Barr, an artillery corporal serving on the Salonica front, up to date with the news.

You would hear that young Walter MacKay is reported killed, but I understand that they have not got word from the War Office. It is a pity if it is true. Two of the McCuaigs who used to be at Laggan are ‘missing’, Neil and John, nice boys they were. John Bland is here just now. He was in Italy and had only been three days in the trenches when he was hit in the eye by some shell splinters and has been in hospital since until recently. He is nearly better but has to wear glasses. He is a 2nd Lieut in the 5th Cheshires. Last night Laggan Bay was livened by the presence of 6 mine sweepers which spent the night there, anchored near the Big Strand. This is the season for Gulls eggs and the Bowmore boys are on the hunt for them Sundays and Saturdays. Farmers are going to be hit hard under the latest Budget, they have to pay taxes on double the rents. Laggan will have to tootle up to the tune of about £31-10/-. If Kaiser Bill has called the tune somebody has to ‘pay the piper’ but folk are well off that have only got to pay instead of fighting. I am going to be hit this time not paying income tax, alas, but through the increased rates for postage, 1½d a go after 1st June. I must ‘huff’ some of my “best girls” to save writing. With regard to writing oftener I would like to do so but I am not so keen on writing letters as I used to be and since the War began one has not so much pleasure in writing, everything being overshadowed by the ‘Great Adventure’. Yet I would gladly do so, when you are so keen to hear news of the old country and of that particular ‘tight little island’ out in the Atlantic. Yes, I wish you were back home again and may the day not be far distant.

Charles MacNiven, an Islay bard with a talent for pawky humour, lamented that the war with Germany was cramping his social life by taking Islay’s young men out of the marriage market.

Tha ’m pòsadh dhìth san rìoghachd seo, se sin aon nì tha dearbhte,

Tha feum air tuille shaighdearan chum oillt chur air a’ Ghear-mailt.

This country’s short of marriages, that’s one thing that’s shown for certain,

For more soldiers are essential now for frightening the Germans.

The Kilchoman bard would be writing in a much more serious tone before the war was over.

In April 1917 the might of America – expressed through its dynamic industrial economy and the youth and vigour of its people – came to the aid of the Old World and entered the war that had been bleeding Europe dry. Once at the front, America’s men and machines would decisively tip the balance and doom the Kaiser’s Germany to defeat. But before the American ‘doughboys’ – the equivalent of Scottish ‘Jocks’ or English ‘Tommies’ – could get to the trenches, they had to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic would exact a heavy toll for that crossing, paid for in young lives. Tides, currents, geology and weather conspire to make these seas hazardous, but when you add the most deadly machines of war that mankind could invent, tragedy beckons.

Throughout the war Germany attempted to lay siege to Britain, starving her of food, men and munitions. Although the Atlantic is wide, the paths of the sea narrow as they approach the great ports of Liverpool and the Clyde. It was in these waters that ships – British, allied and neutral – were most likely to face the wrath of the U-boats of the Kaiserliche Marine, the Imperial German Navy. By the end of the conflict, nearly 15,000 British merchant mariners had lost their lives. Much of the carnage had been wrought by U-boats. One such victim was the Tuscania, a luxury liner converted into a troopship. Today she lies 80 metres below the waves between the Islay peninsula called the Mull of Oa, and Rathlin Island, off Northern Ireland.

A more ancient foe than U-boats is the wild Atlantic that unrelentingly pounds Islay’s rugged western shore. These waters are a constant battleground where the forces of nature are in eternal conflict. One evening in Port Charlotte’s Coastguard station, as the barometer fell and the ferries to and from the mainland went on ‘amber alert’, I quizzed one the men dedicated to cheating the sea of even more lives about the extremes of Islay’s weather. Donald Jones has been a volunteer Islay Coastguard for about 40 years. This, and being a farmer at Coull, on the exposed west coast of the island, has made him an expert on the ferocity of Islay weather. He told me: ‘Down south, if they get a breeze they call it a “gale”, and if they get a gale, they call it a “hurricane”. We really get hurricanes – we get extremes of wind on Islay. And if you have tide and wind coming in opposite directions, that increases the size of the waves. The last place I’d ever want to be is on a ship that’s foundering off the west coast of Islay in a storm.’

The prevailing westerly winds have the uninterrupted breadth of the Atlantic to gather force, and winter storms can bring gusts of more than 100 miles an hour screaming over the island. It was a storm of this power that sank the armed merchant cruiser, HMS Otranto. Today she lies less than half a mile off Islay’s Kilchoman Bay, which is overlooked by the last resting place of many of her crew.

Long ago, Islay’s location – lying between mainland Scotland, Ireland and the islands of the Outer Hebrides – allowed her to become the centre of a great medieval sea power, the Lordship of the Isles. But while the waters surrounding Islay have long been a highway, they are also cruel and treacherous, even in times of peace. Despite the dangers, sailors have navigated these waters since Mesolithic peoples first hunted and gathered in this land and seascape, just after the passing of the last Ice Age twelve thousand years ago. The Celtic tribes of Scotland and Ireland were connected by the sea, rather than divided by it. The Vikings arrived in the Hebrides by sea, and ruled them by sea. Trade with the New World – emigrants one way and tobacco the other – flowed in and out of Scotland though Islay’s waters.

Untold numbers of ships have perished off Islay, and its people became used to a grim harvest being cast up on their shores. In light of what happened to the Otranto, the story of one such wreck is worth retelling. In April 1847, the Exmouth of Newcastle, an old brig crammed with 240 Irish emigrants bound for Canada, was wrecked off Sanaig on Islay’s northwest coast. She’d set sail from Londonderry, but had turned back in the face of a storm. It may be that her captain mistook the Rhinns of Islay lighthouse for the one on Tory Island, off Ireland. In such conditions it was an understandable, but calamitous, blunder. The vessel was dashed against the jagged coast of Islay and, according to a witness, ‘reduced to atoms’. Captain Isaac Booth went down with his ship, and only three of the ten crewmen made it ashore alive. The emigrants were battened down in the hull, and had no chance of escape. Every one perished. It is believed that about 180 of them were women and children. They had been exiled by the poverty and starvation caused by the Irish potato famine, but instead of new lives in the New World, they met a terrifying end on the storm-lashed coast of Islay. A hundred and eight bodies were recovered and buried. It is a hard hike to get to where the unmarked mass grave probably lies, but a monument to the victims, with an inscription both in English and in Irish Gaelic, stands by the road end at Sanaigmore. The tragedy has lingered long in the collective memory and tradition of Islay, and the late Peggy Earl recorded a poignant tale of the disaster. ‘There was living at the time a little girl called Eleanora McIntyre. She found a doll on the shore and took it home with her. The owner of the doll, so the story goes, was buried nearby. That night Eleanora dreamed of a sad and tearful little girl crying for her doll, so the next day she buried the doll with its owner.’

Storms and shipwrecks were once attributed to ‘God’s will’, and whatever was washed upon the shores of Islay was seen by islanders as manna from heaven and theirs for the taking. Even the survivors of wrecks were sometimes plundered. At the close of the eighteenth century, the island’s Stent Committee – a local ‘parliament’ of gentlemen and landowners – condemned the robbery and ill treatment of those washed ashore. ‘This Meeting not only collectively, but individually pledge themselves to use their utmost exertions, not only for the preservation of the property of the individuals, who may have the misfortune to be wrecked on these coasts, but also for bringing to condign punishment all and every such person as may be found plundering from wrecks.’

The islanders seemed to have taken this to heart, for Islay now has a distinguished history of emergency organisations staffed by volunteers. Britain’s Coastguard Service began operations on Islay in 1928, but, according to Donald Jones, a Coast Watch has been operating on Islay for about 150 years. ‘I think it was probably first started to catch smugglers, before it got into rescuing people. Then they built a number of look-out posts, including one at Portnahaven and one at Coull. I imagine the lifesaving apparatus would have been at Kilchiaran farmhouse on the coast where the Otranto foundered. Not that I remember it!’ Donald has been a Coastguard for 40 years and is one of the 16 volunteers currently serving on the island. His son, Andrew, is one of the team, and their colleague, Neillan McLellan, is one of four generations to serve, or have served.

Britons had been brought up to believe that they ruled the waves, not to fear that their great nation could be starved into surrender. But, by 1914, the United Kingdom could no longer feed itself. The nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution had transformed the country as the peasantry left their fields in their hundreds of thousands to work in factories and make Britain the workshop of the world. The British now dined on the fruits of their empire and trading networks, but these imports – which by the outbreak of war made up nearly two-thirds of the UK’s diet – were vulnerable to naval blockade. The blockade was a military tactic that had its origins in the medieval siege; the enemy was surrounded, and then starved into submission. The Kaiser’s Imperial Navy came close to achieving this. By 1916 food was in short supply and prices high. Sugar had gone up by 166%, and eggs and fish cost double what they had in peacetime. There was even a shortage of potatoes. At one point, Britain was just three months from starvation.

Germany had been quick to understand Britain’s vulnerability. It had never been one of history’s great maritime nations, like Britain, France, the Netherlands and Spain, but Germany had now overtaken Britain as an industrial nation and ranked second only to America. Its production of steel had increased by 800% in the three decades up to 1910, and it was a world leader in the production of chemicals and electrical goods. Although economic and technological prowess had allowed Germany to build an effective navy, it knew that it was unlikely to win a Trafalgar-scale battle. Britain’s fleet of Dreadnoughts – each with their ten 12-inch guns mounted in revolving towers protected by 11-inch steel armour – remained the most powerful naval force in the world. But the Germans had been quick to develop new weapons that the Nelsonian Royal Navy was sceptical of – mines and submarines. These, Berlin calculated, could be used to lay siege to Britain and force her into seeking terms. A starved Britain, short of the materials of war, would be no match for the German Army on the Western Front.

In John Buchan’s 1915 novel, The Thirty-Nine Steps, Richard Hannay, the expatriate Scots mining engineer recently returned from South Africa and heading for a host of adventures, neatly outlined German strategy: ‘. . . Berlin would play the peacemaker, and pour oil on the waters, till suddenly she would find a good cause for a quarrel, pick it up, and in five hours let fly at us. That was the idea, and a pretty good one too. Honey and fair speeches, and then a stroke in the dark. While we were talking about the goodwill and good intentions of Germany our coast would be silently ringed with mines, and submarines would be waiting for every battleship.’

Buchan was right. Britain’s long extended coastline offered a multitude of opportunities for a war of attrition against the Royal Navy. German submarines began the war with David and Goliath effectiveness. On 3 September 1914, U-21 sank the British cruiser HMS Pathfinder with a single torpedo. The ‘tinfish’ struck the Pathfinder close to her magazine, blowing her apart and giving her the dubious distinction of being the first modern warship sunk by a torpedo. Less than three weeks later, Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen’s storm-battered submarine, U-9, surfaced to re-charge its batteries after a night lying on the seabed. Sighting three British warships ploughing towards him, Weddigen dived again and fired a torpedo at a range of about 500 yards. The cruiser, HMS Aboukir, suffered a direct hit and sank almost immediately. Believing that the Aboukir had hit a mine, rather than having been torpedoed by an enemy submarine, the other cruisers, HMS Hogue and HMS Cressy steamed to pick up survivors – and were sunk in rapid succession by the U-9. The 500-ton submarine had destroyed 36,000 tons of British warships in just a few minutes.

The Kaiserliche Marine was triumphant, and the Kaiser awarded every U-9 crewman the Iron Cross. The British Admiralty had a collective nervous breakdown. The Commander of the British High Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe – described by historian Hew Strachan as a worrier, a centraliser and a hypochondriac – pessimistically told the Admiralty: ‘It is quite within the bounds of possibility that half our battle-fleet might be disabled by under-water attack before the guns opened fire at all.’ The ensuing war between British Royal and Merchant Navy seamen and the German U-boat crews was described by Winston Churchill as ‘among the most heart-shaking episodes of history’.

The prize scalp of Germany’s mine and submarine strategy was Lord Kitchener’s. He was Britain’s Secretary of State for War, the nation’s most famous living soldier, and the ‘poster boy’ of the ‘Your Country Needs You’ recruiting image. Kitchener was on a diplomatic mission to Russia – to encourage the beleaguered Tsar to stay in the war – when his ship, HMS Hampshire, struck a mine that had been laid by submarine U-75 off Marwick Head on Orkney. It was U-75’s first mission. She would end up sinking, damaging or capturing 15 British, allied or neutral vessels during the war.

The Royal Navy, with its traditions of Trafalgar and broadsides on the high seas, was slow to understand the danger of the lone wolf U-boat prowling undetected beneath the waves. A suggested early British tactic to defeat submarines was for patrol vessels or fishing boats to smash U-boat periscope lenses with a hammer, or put a bag over them. The Admiralty also failed to adopt the convoy system for merchant ships, which were struggling to feed and arm Britain, until well into 1917. It was a mistake that the military theorist and historian, Basil Liddell Hart, called its ‘blindest blunder’. Britain had a lot to learn.

German’s U-bootwaffe were formidable warships. There were only 20 of them in operation at the outbreak of war, but their early successes, and a growing belief that they alone could bring victory to Germany, sparked a building frenzy that saw 309 more launched. Even after heavy losses, Germany still had more than 170 submarines in service at the end of the war.

The fall of Belgium in 1914 gave Germany the use of the Channel ports Zeebrugge and Ostend, thereby extending the amount of time the smaller inshore classes of submarines could spend harrying enemy shipping. The Germans believed that this war of attrition – materialschlacht – could bring Britain to its knees. The Battle of the Atlantic and the wrath of the U-boats reached their height in the spring of 1917. Month on month that year the tonnage of lost shipping rose – 298,000 tons in January, 468,000 in February, 500,000 in March and an unsustainable 849,000 tons in April. That month alone, 413 vessels were sunk. Winston Churchill recalled: ‘The U-boat was rapidly undermining not only the life of the British islands, but the foundation of the Allies’ strength, and the danger of their collapse in 1918 began to look black and imminent.’

U-boats were a triumph of German engineering. The first keel of a German Navy submarine, the U-1, had been laid in 1905. It had serious limitations – but within a decade, ambitious development by engineers, prompted by ruthless military strategy, had created several classes of deadly effective underwater war machines. The UB-77 – which would sink the Tuscania – was of a successful coastal submarine class, the UB type 111. Built in Hamburg, she was commissioned in 1917 and was captained from the beginning by Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Meyer. The UB-77 carried ten torpedoes that could be fired from four tubes at the bow and one at the stern. Under Meyer served two officers and 31 men. Although submarines were feared by the British, the lives of their crews were precarious. The amount of time submarines could spend under water without surfacing to recharge their batteries was limited. Their hulls were thin and, if surprised on the surface, they were sitting ducks. Being a submariner was not a job for the nervous or claustrophobic. Kapitän Meyer described the life of his crew: ‘The submarine service was arduous and dangerous work. The U-boat that left its home port had to reckon with the 50% probability of never returning . . . mines and nets under water, destroyers, motorboats and armed steamer “sub-chasers” on the water’s surface, flying machines and airships above us, all combine to exterminate us. It was serious and novel duty the Fatherland required. For us it was a life of struggle and self-denial.’ The UB-77’s twin diesel engines could drive her along at more than 13 knots on the surface, while her electric motors gave her an underwater speed of less than 8 knots. The description of her as a ‘coastal submarine’ is confusing. It means that she was small, manoeuvrable and with shallow draft that allowed her to hunt in coastal waters – but her range was nearly 9,000 nautical miles.