6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ediciones Pàmies

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

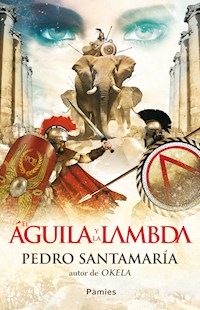

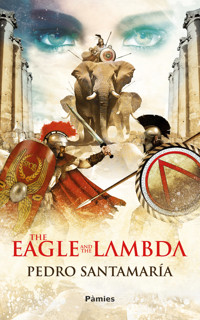

First Punic War, 256 B. C. The struggle between Rome and Carthage has been raging on for over ten years in the bitterly disputed island of Sicily. The Roman Senate, eager to put an end to the conflict, has entrusted Marcus Atilius Regulus, Consul of the Roman Republic, and an outstanding general, the command of four legions and of the greatest fleet ever assembled. His task is to bring the war to Carthaginian soil. After a number of defeats in African territory, the Carthaginian Senate, aware of the danger the city faces, places its last hopes in the expert Spartan mercenary general Xanthippus. However, they do not entirely trust the Greek general. Arishat, the most experienced and best paid courtesan in Carthage, will be instructed to keep an eye on the Spartan while he prepares an army of half-hearted citizens to face the undefeated legions of the Roman Consul. Based on the writings of the Greek historian Polybius, Pedro Santamaría recreates with astonishing realism, accuracy and ever increasing intensity, the fascinating story of Rome's first invasion of Africa.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Eagle and the Lambda

© 2012 by Pedro Santamaría Fernández

English translation copyright © 2017 by Andrés Eriksson and Pedro Santamaría Fernández

© 2018, ediciones Pàmies, S. L. C/ Mesena, 18 28033 Madrid [email protected]

ISBN: 978-84-16970-65-0

BIC: FV

Cover: CalderónSTUDIO

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

To Federico Pacheco Gutiérrez,

for the gift that is friendship.

Index

Part One: The Eagle's Shadow

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

Part Two: The Battle of the Plains of Bagradas

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

Part Three: Four fates

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

XLVII

XLVIII

XLIX

L

LI

LII

LIII

LIV

LV

LVI

LVII

LVIII

LIX

LX

LXI

Author's Note

Acknowledgements

Glossary

«Historia… testis temporum, lux veritatis, vita memoriae, magistra vitae, nuntia vetustis».

(«History is the witness that testifies to the passing of time; it illumines reality, vitalizes memory, provides guidance in daily life and brings us tidings of antiquity»).

Cicero

«History is but a branch of literature».

Pío Baroja

«The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it».

Oscar Wilde

Part One

The Eagle’s Shadow

I

As the slave girl parted the fabric covering the window, light filled the beautiful Carthaginian’s chamber. The sun had only just begun its descent, heading towards the horizon and into the ocean depths. Specks of dust, disturbed by the sudden movement of the fabric, flew erratically in every direction only to settle an instant later in midair and start a feather-like and gentle fall. With a grimace on her face, Arishat turned over in bed to avoid the light. She was neither asleep nor awake, but found herself in that placid moment when the mind shakes off the numbness of sleep and the body begins to awaken. She moved her feet in a circle beneath the covers, gave a low and sedate groan, opened one eye slightly, stretched her limbs with the grace and delicacy of a dancer, covered her eyes with her hands, and smiled.

“It is time, mistress.” the slave girl whispered.

“Thank you, Elissa.”

Arishat yawned softly, as she covered her mouth with one hand. She paused briefly, pensively looking at the villa’s ceiling while her eyes grew accustomed to the light. She then slowly sat up in bed, sliding her feet towards the floor. She felt cold on the soles of her feet, a pleasant and invigorating coolness. A soft tremor ran through her body. She wore a delicate tunic, light as air, white as a dissipating mist. Through it, a dark skinned and divinely shaped body could be appreciated.

“It is late, mistress. Remember, the shophet is expecting you tonight.”

“Yes, I know.”

Arishat rose to her feet, closed her eyes and breathed in deeply, filling her lungs with air. Her perfectly rounded breasts moved only slightly as she did so. The tunic caressed them as they rose like two twin volcanoes emerging from a fog. Her ribs marked her delicate skin. Her belly blurred beneath the cloth.

“Who was the fortunate one last night, mistress?”

“A young merchant from Massalia. It wasn’t bad, though it seemed as if I had been the one to pay him.” The courtesan laughed childishly.

The slave girl could not help but give a hint of a knowing smile while she made the bed. She enjoyed such stories. Arishat approached the window gracefully, as was her custom upon waking, and observed the sky over Carthage. Not a single cloud. In the distance, a woman hummed a monotonous and joyful melody. The racket of the city squares lay far from this well-off area of large and quiet houses, as if wealth attracted peace.

“Did you go to the market, Elissa?”

“Of course, mistress. At the break of dawn as you requested.”

“Did you get the perfume I asked for?”

“Yes, mistress, though it was quite expensive. It has been many days since ships from Alexandria arrived at port. The people are nervous.”

“The people are always nervous.”

“They say…” The slave-girl fell silent. Her mistress did not enjoy hearing the rumours going around, particularly if they were bad, and less so having just awoken. However, Arishat seemed interested.

“What do they say?”

“The price of wheat, which was already sky-high, has doubled within but a few days. People have begun to buy barley instead to make their bread. The price of lamb has increased fourfold, and there are no longer any wine supplies from Euboea. Fewer and fewer ships dock at the harbour with the passing of each day…”

“Oh, stop whining, Elissa! I grow weary of it. You sound like a weeper. It is not your money being spent, is it?” Arishat turned towards the slave girl. “You have not answered me, Elissa, what are the people saying?”

“The people are afraid, mistress. It is rumoured that the Romans plan to come ashore on our coasts. That, as a result, only a handful of foreign ships dock at our harbour, and that that is why everything has become so costly. People huddle in the squares and talk about it. Merchants use it as an excuse to demand more for their goods. Is it true, mistress? Is there really a Roman army headed towards the city?”

“Well!” Exclaimed the Carthaginian amusedly. “Rumours are indeed running rampant after all.”

“Is it true, mistress?” Insisted the slave-girl as she left her duties unfinished, concern creeping into her voice.

“It has been mentioned by a Senator, but it is meant to be a secret, Elissa. I would not however worry too much, the mob is easily agitated, more so when attempting to detail imminent calamities. You should know this by now. Someone must have talked to appear important, perhaps one of those merchants that wishes to justify raising the price of their goods. That is all they are, Elissa; rumours, nothing else.

“They say the Romans are bloodthirsty beasts.”

“I am hungry.” Arishat yawned and stretched delicately.

“They say they steal, murder, rape and burn everything to the ground.”

“As do all men, Elissa.” Arishat replied with a patronizing smile. “As do all men. But we need not concern ourselves with this.”

“How can you say such a thing, mistress?”

“You speak too much with the people at the market. It seems you are only happy when you are worried. We have been at war for the last ten years, Elissa, and our particular situation has only improved with the passing of time. Do you remember that hairy, Spanish mercenary?”

“How could I forget?”

“Well, he had more gold than hair.”

“What do you mean, mistress?”

“That war benefits us. War makes men long for mundane pleasures, and makes them more willing to spend their money to indulge themselves. They make the most of their lives and gold in case the Gods decide to cut their life short. In any event, whoever rules is irrelevant to us. A man is a man, wherever he may come from, and men need to distract themselves from their slow journey towards death. They need to feel immortal from time to time, and that is what I do for them. I do not care if they are a shophet of Carthage or a consul of Rome.” Arishat made a slight pause to change the subject. “Go make my breakfast; you can finish these chores later.”

“But what if they do come ashore…”

Arishat sighed in annoyance.

“First of all, Elissa, in order to reach us, the Romans would have to face our fleet, and let me remind you that no one has ever been able to defeat Carthage at sea. Even if they did manage to surpass that hurdle, they would still have to defeat us on land, and were they to do so they would then have to climb our walls.” The Carthaginian scowled and raised her voice ever so slightly. She was not angry; she merely wished to appear so. “Stop worrying about the Romans, worry more about the beating I will give you if you do not do as I say. Make me something to eat.”

“Yes, mistress. My apologies, mistress.” The slave girl humbly retreated from the bedchamber.

The door closed with barely a sound. Arishat smiled and approached the great polished bronze mirror. She admired herself as she posed. She loved looking at herself in the mirror, affirming that her beauty remained intact despite the previous night’s excesses. It wasn’t only beauty however that her clients sought and found. A dog can be placated in but a few moments, and there were younger women who, for a bit of food, would offer their bodies to panting sailors in the port’s filthy streets; women whose charms would be swept away by the ocean breeze in a matter of months. She was different. In Carthage, having enjoyed Arishat’s delights was a symbol of status, wealth and influence. Carthage was home to even more beautiful courtesans, women with a greater talent for playing the lire, or who danced even more sensuously. The fact of the matter is that sometimes the price of a fragrance hinges more on the seller than on the fragrance itself.

It had been a pleasant evening. That Massilian, despite his youth, had turned out to be an experienced lover, unhurried, skilful and pleasurable. They had been alone and feasted on exquisite delicacies. He had spoken of love and recited poems from his native land and praised her beauty as would a man in love. It was remarkable how some clients, despite paying for her services, seemed to feel compelled to seduce her. She allowed this. She enjoyed the game, even though it was no more than that, just a game. In the end, everything boils down to business.

She slowly descended to the inner courtyard of her luxurious villa. A constant flow of water gave peace to the harmonious place. There, Elissa and her two other slave girls waited with all that was necessary for a delicious and well-deserved lunch. Arishat sat at the table. A child could be heard crying. The courtesan grimaced wearily.

“Apologies, mistress.” said Elissa.

“You should have taken the silphium when I told you to. This is no world to bring a child into. Your howling on the day you gave birth was quite enough.”

“Mistress…” the slave girl pleaded.

“Go on, go.”

“Thank you, mistress.”

A bit of freshly baked bread, some honey, a few dates and an egg, it was an excellent way in which to begin the day, though perhaps a bit late.

As she chewed, Arishat noticed a miniscule ivory flask shaped as an amphora and decorated with Egyptian motifs. It most likely contained the delicate perfume that Elissa had purchased that very morning. She extended her hand and brought it towards her. She uncapped the flask, brought the perfume to her nose, closed her eyes, and took pleasure in the smell of fresh roses. The shophet, a man of refined tastes, would appreciate the fragrance.

II

Repugnant. Nauseating. It was said that lookouts could smell a ship before they saw it. The gang of proletarii clinging to their oars could not have smelled worse even if they had spent their entire lives submerged in the Cloaca Maxima. They did not stop rowing even though it was a consul who entered the quinquereme’s foul smelling hold. Stopping the entire fleet for an absurd ritual was out of the question.

Marcus Atilius Regulus, second term consul of the Roman Republic, walked slowly across the hold. The boards creaked under his feet as he looked upon those who, dressed in loincloths, sank their oars into the water rhythmically, in unison, propelling the galley towards Africa. He felt contempt and disgust, as well as admiration and pride for those men. They fulfilled their duty from their crammed benches to the cadence of an officer’s monotonous whistling. The men drew their oars towards them as they made contact with the water, to later lift them, move them forward, and then sink them again into the ocean. To go down to the bowels of a galley from the upper deck was akin to descending into hell. The oarsmen lived in the dark, with but a few timid glimmers of light creeping through the oar ports, as if with each stroke light threatened to burst into the hold, only to be engulfed once again by the dark.

On deck however, and in comparison, the air appeared clean and pure. Up there, both the world and the Roman fleet stretched as far as the eye could see. Hundreds of sails decorated the horizon and advanced slowly, propelled by the winds and by the arms of more than one hundred thousand men. Down below however, in that underworld, almost at water level and surrounded by the cream of the suburbs of Rome, the universe became reduced to a few wooden benches smelling of resin and tar, and to an annoying whistle travelling the length of the hold. The officer looked to his right and to his left, setting the tempo of the oar strokes.

As soon as they had set sail from Syracuse, and the fleet had adopted the complex wedge formation conceived by the consul to counter any Carthaginian attack, Regulus launched a search that had become personal. He watched the faces grimacing in effort, examining each one for a few moments. They all seemed the same in the dark, but he never forgot a face, and he was certain that the man he sought was among his quinquereme’s oarsmen.

Three hundred citizens propelled that wooden hell, arranged on three different levels. Regulus had already searched each of the faces from the upper levels, and had but fifty left to examine. He would, without a doubt, find him; the thug would not remain unpunished. It was an opportunity for the consul to demonstrate that nothing escaped his notice. He would make an example of this man.

The consul felt a trickle of warm and sporadic rain on his neck while he seemed to dissect an oarsman with his gaze. The liquid flowed down his neck and back, soaking his purple tunic. It took him a heartbeat to realize what was happening. He suddenly and instinctively moved aside, but it was too late to avoid the unpleasant and warm shower that had now stopped falling. Regulus cursed the oarsman from the level above and thought he saw a mocking smile. In any other situation, urinating on a consul of Rome would have mean certain death for any man, but not here, for once an oarsman has taken his place, he is not to stop rowing, no matter the circumstances, until either the galley has reached port, he has been relieved or has died. It was not only sweat that soaked the limbs of those proletarii.

Since the beginning of the year, Regulus had been the father of that great family. A family made up of one hundred and forty thousand oarsmen, sailors and legionaries. He would be generous with the sons that served him well, and severe with those that did not.

The galleys were new, but the wood had already made the foul smell of stale sweat, urine, vomit and faeces its own. After ten years of war and several misfortunes at sea, the gods had smiled upon the city of Rome. The new Roman fleet had been built based on the model of a Carthaginian galley run aground on the coasts of Italy. Only when the Roman engineers had studied the design of this galley did they understand the defeats they had suffered. It was a magnificent vessel, light and robust, which summarized the power of Carthage; a former ally of Rome, and now its mortal enemy. Thus far, the Carthaginians had maintained an undisputable hegemony over the seas, the product of a centuries-old seafaring tradition.

The war in Sicily had gone on long enough. The doomed island was a conglomerate of small Greek city-states, mostly walled, which shared a complex system of treaties, alliances and conflicts, and did not hesitate to surrender to one side or another in succession. Sieges were long and arduous, as both those conducting the siege and those being besieged, felt the sting of hunger; the defenders due to not being able to reach their fields, and the besiegers because feeding large armies in barren lands was an impossible task for their commanders. The latter were also tormented by other evils: the rain, the mud, the heat, the tedium, and the rats.

There were many deserters. At least the besieged had the warmth of their homes and could not go very far. Attacks were far too risky and bloody; too costly in terms of casualties. Occasionally, a walled town would be taken, more often than not as a result of betrayal from those within than due to a valiant assault. Damn Greeks: oligarchs, democrats, tyrants and demagogues, a myriad of decadent people, merchants and charlatans. Damn treasonous and turncoat rats.

Regulus had focused his electoral campaign on convincing the Senate and the people of Rome that Sicily was a deathtrap. He argued that the only way to win that endless war was to take it to the heart of the enemy, and deal them a mortal blow. He offered himself as the best candidate for the task given his experience. If he were to be elected consul again, he claimed, he would subdue Carthage as he had subdued the Salentians during his first term: taking an army to the enemy’s very gates.

The legions of Rome had to disembark in Africa and bring death and destruction with them. This was the only way, he argued, to bring the conflict to a close. His solid arguments and the vehemence with which he presented them won him the position of consul.

At the end of his electoral speech, making use of his powerful voice and energetically lifting his arm, he said to the city’s irate mob: “What I propose, people of Rome, is to go to their homes and drag them from them! Give me the tools, and I shall finish the job!” That roar of hatred, that feeling of commitment still resonated in his eardrums, making the hair on his forearms stand on end. Regulus knew how to speak to the people in their own language.

Like every good Roman, it was not only the glory of Rome which interested the consul, but his own and that of his family. He would do everything in his power to ensure that his accomplishments remained in the memory of all; seared into history, remembered in times to come.

He had a year ahead of him as consul, over three hundred quinqueremes under his command, with four entire legions on board. Additionally, two thousand horses, provisions for the expedition, and a vast amount of weapons crossed the seas in transports that were towed by galleys. The fleet sailed on slowly, heavily loaded with all that was necessary for the task. The effort made by Rome and its allies was vast. Entire forests had been cut down to create the Republic’s new fleet.

It was the largest expedition ever launched. Regulus however had two problems. One, which he hoped to avoid, was the Carthaginian fleet; the other, inevitable, was Lucius Manlius Vulsus Longus, his co-consul. A stupid man, an obstinate Patrician, a bloodsucker, who instead of being sent to Sicily as was intended, had managed to convince the Senate that such an ambitious campaign as this required both magistrates. Why was Longus a bloodsucker? Because he was stupid, but not a complete fool. If the operation proposed by Regulus led to victory over Carthage, the honours and spoils would be for them both. If it failed however, then Longus would no doubt find a way to avoid any responsibility for it in the eyes of the Senate. Regulus would have had conceived the misbegotten plan after all. History would be the judge. In the end, that which is reckless differs from the audacious in one aspect alone, the result.

Longus, as any Patrician, seemed not to have assimilated the Lex Licinia Sextia that had been in place for over one hundred years. According to the law, of the two consuls elected every year, one was to be a Patrician, the other a Plebeian. Prior to the enactment of said law, only Patricians could be made consuls, and many still considered the edict as temporary; a river that has overflowed and sooner or later must return to its normal course. In their opinion, only the most distinguished families of Rome should guide the fate of the city. Guardedly, many Patricians attempted to hinder the actions of their Plebeian counterparts.

“Sir” whispered the submissive and alarmed voice of a legionary behind Regulus.

Despite the stench of the hold, the soldier did not cover his nose or mouth out of respect for the magistrate. Regulus turned slowly after having carefully observed another of the faces that rowed, which bore a horrible wart on its nose as if it were a trophy.

“Speak, solider.”

“The tribune requires your presence in the command tower. A group of ships has been sighted to the West.”

“How many?”

‘Several, sir.”

With a gesture of indifference, Marcus Atilius Regulus, second term consul of the Republic, suspended his personal search in order to return to the upper deck.

III

Aulus Porcius Bibulus had not been able to avoid smiling as he dragged the oar towards himself. The night in Syracuse, prior to setting sail, had been a good one. And though he would have preferred to sleep until late the next day, tempting fate was not advisable. His mouth was still dry from all the wine he had drunk during the two hours he had been away from his post. He still felt the tickling sensation from that Syracusan harlot’s lips between his legs. For one measly coin she had fulfilled his desires in a filthy city corner. But, above all, he could still hear the tinkling of coins those two sixes had won him in that dirty tavern. Two sixes. He could not believe his luck. Could things get any better?

“Hey Bibulus” said the man at the oar to his right. “Did you win last night?”

“I was on watch yesterday” said Bibulus deadpan.

“Come now, your face tells that you had your fill of wine. How much did you win?”

“As I told you, I was on watch.”

“You’re a damn liar.” His friend replied amused.

“Silence!” roared a soldierly voice.

“Consul of Rome in the hold! Do not stop rowing!”

A consul of Rome indeed, what an honour, Bibulus thought to himself.

It was simply a matter of being silent for a bit. Any senator would be hard pressed to remain on the lower level of a quinquereme for more than a brief spell. The sheer smell drove them away. This would also give Verrucosus, the man to his right, time to forget about their conversation. At that speed, between oar strokes, one could speak calmly. Another unwritten convention held that one had to show effort on one’s face when a magistrate visited the nasty place.

Rowing was pleasant enough, much better than running around the Suburra looking for work day in and day out; work that, more often than not, remained unpaid, and stealing when there was nothing to eat.

Joining the fleet had been, without a doubt, the best decision he could have made. You did not have to wonder when the next meal would come, wages were paid on time, and the galleys docked in places where no one knew you, thus neither your actions nor your face were remembered. Then there was the prestige of belonging to the fleet of the Republic and, though this did not grant the reputation of being a legionary, people were wary of you in taverns and brothels. In the Suburra, there came a moment in which everyone knew who you were, and that had become uncomfortable. Bibulus now belonged to something much greater, and though he was probably one of the most expendable men on this expedition, once they found themselves in occupied or allied territory, such as Syracuse, any Roman citizen became important simply because they were a descendant of the she-wolf.

Of his mother, Bibulus remembered one thing, the constant same old story that he was the son of an important man, the result of a passionate night with a Patrician. The cubicle they called home was at the highest and narrowest point of an insula. It was one of those unstable four storey buildings that littered Rome and seemed to have rained down on the city, or been scattered around and piled up by a mad giant. These often burned down with amazing ease and fury, or simply collapsed one day, burying their occupants.

At some point, his mother must have been beautiful, but by the time he was six years old she died looking like an old woman. Someone told him she had died from a disease typically resulting from hosting men in her home.

At that age, his growling stomach soon made him forget his grief. A few days later he had to abandon the mouldy dwelling when the owner demanded the excessive rent that was owed. That ugly man did not care that the woman was dead. Little Bibulus slipped through the owner’s fingers when he declared his intent to sell the boy as a slave in order to recover what was owed him. Ever since, the streets had been the boy’s home, and finding food his only occupation.

Despite those initial hardships, the truth is that fortune usually smiled upon Bibulus. He would tend to win at dice, he was considered witty, a ladies’ man, and known as a handsome rogue. The amount of physical labour he had performed before joining the fleet had allowed him to develop an impressive musculature, one his body seemed to have been destined for. Unloading sacks and amphorae, pushing or pulling heavy carts, carrying loads of bricks… each day was different. When work was scarce and hunger came, he would hide in the shadow of night to steal, developing a feline instinct and a stealthy nature despite his muscular build. And so, when all that was talked about in the city was that a great levy was being prepared for the fleet and the legions that would sail to Africa to conquer Carthage, Bibulus decided to enlist. He had no idea what Africa was, much less the ocean, but regular pay, food, and plenty of bounty was being promised.

When his turn came before one of the tables where three men in military uniform asked for his name, the one that was seated, aside from having a slightly mocking smile when Bibulus replied, looked him up and down and simply said, ”Oarsman, lead galley”. Another wrote something on a wax tablet, and the third handed over a tinkling pouch.

The contents of the small pouch did not last long in Bibulus’ hands, soon filling the pockets of a barkeeperand a prostitute.

Aulus Porcius Bibulus. Only nobles had such long names, but given that he always said he was the descendant of a Patrician, the sarcastic Suburrans had added it to his praenomen, which reminded them of a Greek flute, a nomen: Porcius, which meant pig, and in the custom of the most illustrious families, a cognomen, Bibulus, which meant drunkard.

And yes, the day could get better. A trickle of urine, to which they were already accustomed, had fallen on the consul’s neck. Bibulus could not help but grin. For some reason, the consul stopped in front of each and every one of the oarsmen and examined their faces for an instant. It was quite peculiar. When the consul was observing Verrucosus, the man to Bibulus’ right, a legionary came down to the hold and whispered something in the consul’s ear. The consul turned on his heel and left, soaked in urine.

Like many others around him, Bibulus made a snorting sound in order to avoid laughing. The sound masked his amusement, making it seem like a grunt of effort. Those are the little things that make one believe that the Gods exist.

“So?” Verrucosus continued. “Did you win a lot then?”

“I already told you, I was on watch.”

“Fine. Remember, tonight during the respite, you owe me a game.”

Verrucosus was an inveterate loser, a farmer from the outskirts of Rome who, overwhelmed by debts, had abandoned his small piece of land to enlist. Like Bibulus, he lacked the means to purchase the necessary gear to become a legionary, and thus ended up on the benches of the fleet. He had a horrible and giant wart sprouting from his nose. It was, he said, the only thing he had inherited from his father, that, and a mountain of debt. He was a likeable fellow; he never became angry over anything. He lacked cunning, and ever since he had discovered the passionate world of dice, he did nothing but gamble and lose.

“Combat stroke!” yelled a voice that gave orders, one to which Bibulus had yet to put a face to.

The whistling began anew at a quicker pace, and the oarsmen increased their speed.

“Another of the consul’s whims.” said Bibulus to Verrucosus without being able to say any more. The effort would now make it impossible for them to speak.

Ever since they had left Ostia, they had gone through an endless amount of these drills. It was as if the consul had come down to the hold to look at the oarsmen before giving the order, and then returned to examine them in order to verify the effects the effort had on them. There was however something different after hearing the word combat, something that had not happened until this very moment in any of the other drills. The legionaries filling the galley now began to receive orders as well.

Hundreds of feet on the galley’s deck made the wood creak and shake. The heavy footfalls of men gearing up for combat, preparing for battle, made it seem as if the entire deck would come crashing down at any moment.

IV

Marcus Atilius Regulus tumbled back slightly as he felt the sudden momentum of the ship under his feet moments after giving the order. A myriad of sails could be seen from the command tower located at the bow of his flagship. They slowly materialized on the horizon blocking the fleet’s path. Their sheer number was difficult to calculate, but they were Carthaginian vessels. Infernal machines, fast and manoeuvrable, crewed by expert sailors and well trained oarsmen.

Yesterday, the Consul had fantasized about sailing by unnoticed. But little more than a fantasy it was, for he knew that to keep an invasion of such magnitude a secret, when rumours of its launch had been spread to the four winds, was impossible. The streets of Rome and Syracuse were plagued with Carthaginian spies, and so they would have known exactly when the Roman fleet had left Syracuse, and the route it would likely take. The Carthaginians would also have a rough idea of the fleet’s composition and of the wedge formation it had adopted.

The small township of Ecnomo, on the Sicilian coast, could be seen to the North. To the South lay the vastness of the ocean. The sun was blinding, the sea was calm, and seagulls cried out at each other oblivious to the madness of men. The galleys of Regulus and Longus were at the head of the fleet, the vertex of the perfect triangle formed by the three hundred vessels under their command. The wedge formation protected the slower and heavier transport ships at the rear, which were towed by warships and loaded with horses and supplies. The rearguard was itself protected by a third squadron of Roman galleys, which due to their position within the formation, Regulus had named the “Triarii of the Fleet”. Conversely, the Carthaginian fleet was deployed in a long line from North to South, the flanks of which were slightly in advance of the main body. The centre of the enemy display appeared weak.

The Consul squinted and observed the Carthaginian positions. He stood pensively for an instant, scrutinizing the horizon, and then smiled slightly to himself. He then crossed his hands behind his back, as was his custom before giving an order.

“Message for Longus.” He said to the officer at his side. “We are launching the attack. Lower the sails and secure the masts, combat formation.”

“Sir?” replied the officer that stood next to him, confused.

“Attack my good, Lucius, attack.” Replied Regulus with absolute confidence, never taking his eyes off the Carthaginian ships.

Lucius’ trepidation was understandable. The Roman fleet was loaded to the brim with troops and supplies. As such, the galleys were slower and less manoeuvrable than those of their antagonists.

The fleet’s rams would be easily avoided by a lighter, more experienced enemy, an enemy that would most likely slip between the Roman ships like eels and charge them on the side, only to immediately pull back and search for a new target as their initial victim was swallowed by the ocean. Yes, it may well be madness, but retreating was not an option, neither was standing still. If the Carthaginians wanted a battle, Regulus would give them one.

Regulus was impetuous, as befitted a Roman. His term in office was for only a single year after all, a year during which he would either succeed or fail. There was no room for the doubt or hesitation brought about by the opinion of a subordinate. Furthermore, his intuition as a soldier told him the Carthaginians had made a mistake: their line was long and lacked depth. A cavalry charge in wedge formation came to his mind. If Regulus was able to break the enemy lines at their centre, dividing their forces, victory would be assured. Simple.

The Carthaginians did indeed have their rams, but the Romans had the corax: a drawbridge located on the bow of their galleys, invented by one of those mad Greek engineers, which allowed a military force to bring land warfare to the sea. The ingenious artefact fell on the attacking ship, trapping it against the Roman galley, which would then send its legionaries across it and spread death and destruction on the enemy vessel. Due to the natural disdain Romans had for all things Greek, Regulus had named the ingenuous contraption corvus, a literal Latin translation of the Greek word “crow”.

It did not take the Roman fleet long to achieve a certain degree of speed, with the purpose of engaging the Carthaginian line. Thousands of oars slammed into the liquid plain in unison, propelling the powerful fleet towards the enemy. Lucius, who observed his superior’s composure with admiration, felt as if an iron fist had gripped his heart in anticipation of the imminent battle. He was proud to serve under such an audacious man. Regulus was a true Roman: courageous, proud, tenacious and austere.

The quinqueremes cut through the water as a blade through cloth. The ocean parted before the Roman Consul, waves caressing the sides of his galley. It was an action that, judging by the Carthaginian reaction, the enemy was not expecting. Regulus watched with satisfaction as the Carthaginians before him began to turn their vessels around and retreat with astounding speed. He smiled and slapped Lucius on the back.

“The initial rhythm of a battle determines its outcome.” he said as if speaking to himself. “An impetuous attitude tends to win battles, Lucius.” Regulus pointed towards the Carthaginian fleet. “Do you see? They did not expect us to react, and as a result have become disorganized.”

They would break the Carthaginian centre by exploiting the disarray, and would soon celebrate victory; a victory that, if enough enemy ships were destroyed, could earn Regulus a triumph, as long as the enemy did not engage in full flight. After all, there can be no battle if the enemy chooses not to fight. Regulus looked to his left. Longus and his squadron had not lagged behind. At least the fool had understood that this had been the right decision.

Initially, Regulus had observed undaunted as both Consular squadrons rode the waves at a good clip, gaining on the enemy without braking formation. They headed directly towards the fleeing Carthaginian line. Something began to seem odd however. Despite the Roman fleet’s weight, they continued to gain ground on the enemy, the Carthaginians were moving at a lesser speed. He did not understand at first. They were in flight, but continued to reduce their speed?

Suddenly, the Carthaginian fleet began to turn as one, decorating the surface of the ocean with their wake. This time they moved south, against the wind.

“I did not think the Carthaginians foolish enough to lose the lead they have on us and offer us their flank” said Regulus. “By sailing into the wind they have ensured that their retreat shall be delayed. I think we have them, Lucius.” The officer nodded satisfied.