Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

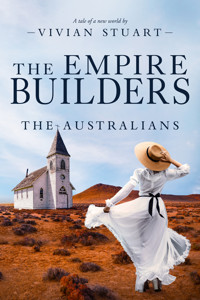

- Serie: The Australians

- Sprache: Englisch

The seventeenth book in the dramatic and intriguing story about the colonisation of Australia: a country made of blood, passion, and dreams. Destinies intertwine and brutal battles ensue to secure a brighter future. During the 1860s, Australian settlers, among them Lady Kitty Broome and Adam Vincent, venture out on new, exciting adventures which will lead to a war between cultures, friends and lovers, as they fight for the future of their world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Empire Builders

The Australians 17 – The Empire Builders

© Vivian Stuart, 1986

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2022

Series: The Australians

Title: The Empire Builders

Title number: 17

ISBN: 978-9979-64-242-8

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

The Australians

The ExilesThe PrisonersThe SettlersThe NewcomersThe TraitorsThe RebelsThe ExplorersThe TravellersThe AdventurersThe WarriorsThe ColonistsThe PioneersThe Gold SeekersThe OpportunistsThe PatriotsThe PartisansThe Empire BuildersThe Road BuildersThe SeafarersThe MarinersThe NationalistsThe LoyalistsThe ImperialistsThe ExpansionistsPROLOGUE

Her Majesty’s steam-screw frigate Kestrel arrived in Port Jackson to relieve H.M.S. Galah on New Year’s Day, 1859. The Galah’s commander, Red Broome—newly promoted to post rank for his services in India during the Sepoy Mutiny— swore aloud as he watched the new arrival come to anchor in Watson’ Bay, for she was two weeks ahead of her anticipated appearance on the station.

His own ship had completed her refit only ten days previously, and with the damage she had sustained on her passage from Calcutta now repaired, he was unhappily aware that he would have to sail for England to pay off as soon as he had handed over his responsibilities on the station to the Kestrel’s commander.

Nevertheless, it would be inhospitable in the extreme were he not to make his successor welcome. A dinner party at his house would best fill the bill, Red decided, after the formalities were completed. His wife, Magdalen, was a skilled hostess; she would be as distressed as he was by the Kestrel’s unexpected early arrival, but in spite of that, he knew that he could depend on her to make the meal a memorable one, since it would be his farewell, as much as his relief’s welcome to the colony.

He had cause, however, to regret his impulsive decision during the ensuing days, as he prepared for departure. The Kestrel’s captain, Commander Rupert Harland, proved to be a small, bombastic man, considerably older than Red himself and several years senior in service, his lack of promotion the result of the findings of a court of inquiry, which had held him to blame for the death of a midshipman serving under his command in the West Indies.

The boy had been the youngest son of the Second Sea Lord and because of that, Harland confided sourly within half an hour of meeting Red for the first time, Their Lordships had kept him on half pay for the past five years. His appointment to the Kestrel had come only after the death of the vengeful old admiral, and the last station he had wanted was the one he had been ordered to take up.

“A damned convict colony!” he asserted belligerently. “And for two years, God forgive them, for I cannot!” He eyed Red’s tanned, good-looking face with sour displeasure, mentally calculating the years between them and clearly finding the difference in their ranks a cause of resentment that he took no pains to hide. “Damme, I had my lieutenants’ commission when you were still a newly joined mid! Served under the late Admiral Stirling, didn’t you?”

“I did, yes—the Success was my first ship. But—”

“And you were born out here, I was told?” Harland made it sound like an accusation, and Red stiffened.

“Yes, that is so. I—”

“Then no doubt you’ll find it a wrench to leave. Devil take it, I’d give my eyeteeth to exchange with you, Captain Broome! I’ve a wife and family in Dorset, and after skimping and saving on half pay for five long years, I cannot afford to bring them out here.”

And he, Red thought, as he listened with restraint to the tirade, would gladly have given more than his eyeteeth to make the exchange, had that been possible.

His instinctive dislike of his successor came to a head within two days of making his acquaintance. Claus Van Buren—now one of Sydney’s most valued merchant traders—brought his beautiful American-built clipper Dolphin into port when Red was with Harland in the commodore’s official residence, overlooking the harbour. Harland had watched the schooner with admiring eyes—despite the fact that his command was powered by auxiliary steam, at heart he was a sailing ship man, which was a point in his favor—and, on his expressing interest in the superbly designed vessel, Red offered to arrange a visit of inspection for him.

Having known Claus since boyhood, it did not occur to Red to mention the shipowner’s mixed ancestry; Sydney society had long since accepted him for what he was, and in any event Claus’s dark skin was evidence enough of his native Javanese blood, his aristocratic Dutch name proof of his breeding.

The vist to the Dolphin went well initially, for Rupert Harland’s interest was genuine, his knowledge of clipper design remarkably comprehensive, and his manner toward Claus, if a trifle condescending, was polite. Claus’s pretty American wife, Mercy, and their two young sons were on board, and when the lengthy inspection was at last completed, Mercy came on deck to issue an invitation to the visitors to take refreshments in the great cabin.

Entering and observing the beautiful panelling and luxurious fittings of the cabin, the hand-carved dining table and chairs, the silver, cut glass, and exquisite bone china on the sideboard, Commander Harland was visibly impressed. His manner changed, the hint of condescension vanished. He bowed respectfully over Mercy’s hand and confessed his readiness to take a cup of Peking tea, and as she poured it, he continued the discussion he had been engaged in with Claus concerning the Dolphin’s rig and cargo-carrying capacity.

“I’m surprised you did not have her ship-rigged. If you want speed—and I presume you do, if you engage in the wool trade—I should have thought you—” He broke off, startled, his jaw dropping in shocked astonishment. “Who in the world—”

The curtain covering the cabin doorway had parted, and the young Maori chief Te Tamihana came in, with the easy familiarity of long custom, to accept a teacup from Mercy Van Buren and take his seat at the table.

Red, aware of the chieftain’s friendship with Claus, and having been previously introduced, greeted the young Maori by name, but Harland continued to stare at him as if he were an apparition from another world. With his heavily tattooed face and lithe, copper-coloured body, which was naked save for the woven flax kilt draped about his waist, Te Tamihana’s appearance as he solemnly sipped tea was, perhaps, understandably startling to a newcomer from England. Even so, Red was unprepared for his brother-officer’s reaction.

Harland leaped to his feet, his teacup falling from his hand, as he exclaimed furiously, “In God’s name, Broome, you may have gone native, but I have not! I was prepared to stretch a point where Captain Van Buren was concerned, but I cannot be expected to sit at table with a damned aboriginal savage. That is asking too much, sir, damned it is!”

Te Tamihana eyed him in mild surprise and then, carefully setting down his own cup, observed in faultless English, “If you will forgive me, Claus, I will go on deck with the boys. We were, as it happens, in the middle of a most entertaining game, in which I was hard put to hold my own. Excuse me, please, Mrs. Van Buren.”

No one spoke until the curtain had swung back behind him, and then Claus, with a warning shake of the head in Red’s direction, said coldly, “The young man you have just insulted, Commander Harland, is not an Australian native. He is, in fact, a Maori—one of the most influential chiefs in New Zealand’s Bay of Islands and an honoured friend of mine—like yourself, a guest on board my vessel. He—” Harland attempted to interrupt him, but Claus would have none of it. “Hear me out, Commander. I spend a great deal of my time in New Zealand, where I have extensive trading interests—more important by far than my interest in the wool trade these days. These interests are based and, indeed, are largely dependent on the friendly relations I have built up over the years with the Maori tribes. In all my dealings with them I regard them as equals and I respect their culture, their standards, and their honesty. Sentiments which they reciprocate, sir.”

Rupert Harland recovered himself. Very red of face, he retorted with a sneer, “That, for one of your colour, is understandable, Captain Van Buren. Like calls to like, does it not? Unlike ourselves, the Dutch, I believe, tend to intermarry with their subject native peoples, and clearly you—”

Angrily, Red attempted to restrain him, but once again Claus shook his head. “Permit me to explain the current state of affairs in New Zealand to this gentleman, Red, if you please. If he is to replace you on the Australian station, it is important that he should understand.”

“Then carry on,” Red invited, tight-lipped.

“Certainly.” Claus turned to face Harland, his dark eyes cold but devoid of anger. He waited until Mercy, meeting his gaze, excused herself and slipped away, and then he observed quietly, “I must tell you, sir, that there could well be war in New Zealand in the imminent future, more serious than the conflict of twelve years ago. Settlement has increased tenfold, and everywhere on the North Island it is expanding with alarming rapidity—and I do mean alarming because the settlers are bringing trouble on themselves. Too many of them are greedy and dishonest, and they pay scant heed to the Maoris’ just rights and grievances. They cheat and dispossess them of their land, lull them with false promises, and fail even to make their fair reparation for the vast acreages they have seized.”

“New Zealand is a British colony,” Harland blustered. “The settlers have a right to land, under the treaty signed by the Maori chiefs.”

“True,” Claus conceded, with another warning glance at Red. “But the Maoris were there many years before the first white man set foot on New Zealand soil. And, sir, the Maori people cannot be dealt with as the natives of Tasmania were—they cannot be banished to some barren island to die of disease and neglect. There are too many of them. They are a proud, strong, and warlike people—they will fight for what is theirs. And, sir, the settlers are in no state to join battle with them—they are mostly farmers and merchant traders, like myself. Or missionaries. If the Maori tribes are provoked into war, and if the tribes unite under an elected king, as they seem likely to do, it will take a great many of your Royal Navy’s ships and Her Majesty’s fighting regiments to prevent a bloodbath. I ask you to remember that, Commander Harland.”

Claus again looked across at Red and added regretfully, “I’m distressed to learn that you have been ordered to England, Red. I had hoped, I am bound to tell you, that you and Her Majesty’s ship Galah would have been permitted to remain on this station, in order to pour oil on troubled waters.”

His tone throughout had been conciliatory, but Rupert Harland was in no mood to respond to conciliation. He picked up his cap, jammed it wrathfully onto his head, and prepared to depart, glaring at Red when he remained seated and made no move to follow him.

“In my view,” the Kestrel’s commander said spitefully, “the only way to deal with recalcitrant native populations is by force. It is all most of them understand. And if it’s left to me, Van Buren, and your Maori friends engage in plotting and rebellion, my ship’s guns will not be silent. There may be a bloodbath, as you predict—but it will be Maori blood that is spilled, not British. I bid you good day, sir.”

He stormed out of the cabin, and Red said apologetically, “The devil take the fellow! I’m sorry I brought him aboard, Claus—deeply sorry.”

“Let him go,” Claus responded. “Stay with us for dinner, Red. You could not possibly have known how he was going to react. Besides,” he added, smiling, “if you stay, you can at least pour some oil on Te Tamihana’s troubled waters . . . and believe me, my friend, it is necessary. That young man is inclined to support the King Movement, and who can blame him?”

Red frowned. “You think that this King Movement is a serious threat to peace, then?”

“Well . . .” Claus hesitated. “It would have been, if the great Hongi Hika had still been alive. No doubt your father has told you about him—I believe he met Hongi once.”

“Yes—yes, he did, when he was first lieutenant of the Kangeroo.” Red’s frown lifted. “I understand it was quite an encounter, the way my father tells it. He admired Hongi.”

“So did the Maoris. Hongi led by right of conquest—no tribe dared to oppose him. He armed his warriors with muskets when the rest had only spears and tomahawks, and on his return from a visit to the English court, he appeared in a suit of armour the King had presented to him. His prestige was immense.”

“Is there no chief of Hongi’s stature now?” Red questioned.

Claus shook his head. “No, there is not. The two great tribes—the Ngapuhi in the land north of Auckland and the Waikato to the south—have a long history of feuds, with scores of ancient wrongs still to be avenged. Neither was willing to bow to a king chosen by the other.” Claus spoke thoughtfully. “The Ngapuhi did agree to meet a deputation from the Waikato some time ago but then announced that they would remain loyal to the Queen of England—mainly, I think, out of respect for the late governor, Sir George Grey. The Maoris always trusted him, believing he was more on their side than that of the settlers. They’re not so sure of his successor, Sir Thomas Gore-Browne.” Claus’s broad shoulders rose in a shrug. “In any case, the result is growing ill-feeling, which could lead to bloodshed. And the southern tribes did elect their own king.”

“Did they, now? Is that good news or bad?”

“In truth I do not know, Red,” Claus confessed. “The man they chose—Potatau, he’s called—is a famous old warrior, held in almost universal esteem. But he is an old man, and his fighting days are over, so I personally doubt whether it lies in his power to unite all the Maoris against us—or even whether he wants to. Unfortunately, his son, Tawhiao, who is likely to succeed him, is a young hothead, who could make trouble, given the chance.”

Claus was silent for a moment or two, lost in his own thoughts, and then he said, brightening, “I suppose you’ve heard that your brother-in-law, the gallant Colonel De Lancey, has decided to settle in New Zealand instead of remaining here?”

“Yes,” Red confirmed. “He told me.”

Will De Lancey had gone initially to the Illawarra district south of Sydney, seeking suitable land and determined, after his harrowing experiences in India during the Sepoy Mutiny, to turn his sword into a ploughshare, as he wryly put it. But his friend Henry Osborne, owner of the Mount Marshall property, had died during his absence, and the price of good land in the fertile Illawarra had risen to almost prohibitive heights.

“I’ve come too late to acquire land as the squatters did,” William had said regretfully. “Henry, I’m sure, would have sold me some of his at a reasonable price, but, alas, he is no longer with us, and on a soldier’s pay I could not possibly afford what is presently being asked. And besides Mount Marshall holds too many memories of my darling Jenny—we spent part of our honeymoon there, you know, and when I went back I found I could not drive them from my mind. New Zealand offers better opportunities, and . . . well, we should be making a completely fresh start, the boy and I.”

Claus, as if reading Red’s thoughts, offered, smiling, “I ran into the colonel in town, after we made port, Red, and he’s booked passage to Auckland with me for himself and the youngster he had with him—what is his name?”

“Andrew Melgund,” Red supplied. “He was orphaned in the mutiny—both his parents were massacred at Cawnpore. And Jenny, my poor little sister Jenny, who also died there, saved the boy’s life.”

“He struck me as a fine boy,” Claus observed.

“He is indeed,” Red agreed. “In fact, I think he’s been the means of saving Will’s sanity.” He added soberly, “I hope, for Will’s sake, that peace will prevail in New Zealand, Claus. After the Crimea and the Sepoy Mutiny, Will has had his fill of war. When do you sail?”

“In about ten days’ time. We’re living on board and not opening the house for so short a stay—Mercy and my boys are coming with me, as always.” There was a warmth in his voice. “I’m a fortunate man, Red. I live the life at sea that I love, and my wife and family share it with me. In that respect, I’m a good deal better off than you are. For all your exalted rank in Her Majesty’s Navy, you will not be permitted to take Magdalen and your little daughter with you, will you, when you sail for England?”

“Sadly, no,” Red answered. “Their Lordships of the Admiralty have withdrawn that privilege from us. I shall have to book them passage in a commercial vessel.”

“I have a wool clipper—the Dragonfly—sailing next month,” Claus offered. “She’s a ship of seven hundred tons burden, and I could give them passage. But of course Magdalen may prefer to make the voyage by steamer, although I can promise that my Dragonfly will make a fast passage. And,” he added, his smile widening, “I could quote you privileged rates.”

“I’ll speak to Magdalen about it—I’m sure she will jump at the offer.” Red returned his friend’s smile, the earlier unpleasantness with Commander Harland almost forgotten. “My grateful thanks, Claus. You are a good friend.”

When the dinner party to welcome the Kestrel’s new commander and to bid farewell to his predecessor on the Sydney station took place two days later, at Justin Broome’s Elizabeth Bay house, the atmosphere—Red noted with dismay when he arrived—was unusually tense. Not surprisingly, it was Rupert Harland who proved to be the cause of the trouble.

The Kestrels commander, while admitting he was the only stranger in what was largely a family gathering, had made not the smallest effort to respond to the friendly overtures he was offered. His manner was aloof almost to the point of rudeness, as if he were intent on emphasising his superiority to the members of a colonial society who, he clearly supposed, had sprung from a discreditable convict ancestry and, as such, could not expect to merit the courtesy he would normally have displayed.

Magdalen, who had taken over the kitchen of the Elizabeth Bay house from an early hour and given much thought to the dishes that were served, was at first worried and then affronted by the newly arrived commander’s failure to do justice to the excellent fare. As course followed course and Rupert Harland picked disdainfully at the contents of his plate, Red observed his wife’s increasing embarrassment, and his anger rose. Devil take the fellow, he thought wrathfully, hard put to it to contain himself and regretting the impulsive invitation he had issued on first acquaintance with his successor. This was a gross and ill-mannered abuse of hospitality, it— He caught his father’s eye and saw, to his astonishment, that Justin Broome was amused rather than offended by Harland’s behaviour.

As the ladies rose to take coffee in the withdrawing room, his father, having held the door for them, paused by Red’s side. “Don’t worry, Red,” he said in a low voice. “I’ve met his kind before. Indeed, I once served under one of his kin—Captain John Jeffrey, of His late Majesty’s ship Kangaroo. The officer who, you may recall, fell foul of the famous Hongi Hika in New Zealand some years ago. I must have told you the story.” He smiled. “Mr. Harland will learn because we shall teach him, rest assured of that.” Moving back to his own seat at the head of the table, Justin Broome raised his voice. “Magdalen gave us a memorable dinner, Red. Now, my dear boy, be seated and we’ll take a glass of port and drink to your safe return to English shores!”

The toast was duly proposed and drunk, and as cigars and pipes were lit and the port decanter circulated, a brief silence fell, and Red heard his father say, “Ah, Commander Harland, I’ve been thinking . . . I fancy that I made the acquaintance of a relative of yours. It was quite a long time ago—indeed, it must be well over twenty years, soon after the first settlers moved from Holdfast Bay to what is now the city of Adelaide, in South Australia. You have not been out here before yourself, have you?”

Rupert Harland’s fleshy face was, to Red’s surprise, suffused with angry colour. For a moment, it seemed as if he were about to choke with indignation, but he recovered himself and said in a hoarse voice, “No—no, sir, I have not. I—er—I’m not quite sure to whom you are referring.”

“Are you not?” His father, Red observed, appeared in no way put out. In a conversational tone, he gave a brief description of the difficulties that had faced Adelaide’s early settlers, who had been ill prepared for the conditions they were called upon to endure—the lack of labour, of adequate shelter and food, in addition to the prolonged disagreement between the governor, Captain Hindmarsh, and the surveyor general, Colonel Light, as to the final site for the town.

“Those unfortunate people were close to starvation,” Justin Broome went on, sagely nodding his white head and avoiding Harland’s suddenly pleading gaze. “They had money, most of them, but money could not buy them what they so desperately needed. Until—” His tone changed, and now, Red saw, he was looking at the Kestrel’s discomfited commander with alert and searching blue eyes. “Until the arrival of one of H.M.’s sloops of war—the Ringdove, if my memory serves me aright. Her purser supplied them with most of the stores from his ship, at considerable personal profit it was said . . . and scarcely with Their Lordships’ approval.” Again he paused, and Harland’s face drained of its hitherto hectic colour. “I remember the matter. . .” His father had the attention of the whole table now, Red realized, and no one spoke, as he went on, “because I was a member of the board of inquiry that subsequently sat, here in Sydney, to look into it. The purser’s name, Commander Harland, was the same as your own, to the best of my recollection.”

“Mine is not an uncommon name, sir.” Harland was on his feet, prepared to bluster. “I know nothing of the—the affair, I—and now, if you will be so good as to excuse me, sir, I will take my leave. I—er—that is, I thank you for your hospitality, Captain Broome.”

“Be so good as to see the commander out, John,” Justin requested. There was a gleam of satisfaction in his eyes, Red saw, as his younger brother rose to comply with their father’s courteously voiced command.

Justin Broome waited until Johnny returned and then, smiling broadly, answered Judge De Lancey’s explosive, “Good God, what was all that about, Justin?”

“A little ploy devised by the commodore and myself, George, because he too has had about all he could stomach of Harland’s arrogance.” Justin resumed his seat. “To be truthful, I’d forgotten all about the Ringdove affair, but the commodore chanced to recall that he was also a member of the board of inquiry—he was first lieutenant of the old Buffalo at the time. And the purser was our Harland’s father. We checked the records, so he can deny it all he likes—the proof is there. Needless to add, Harland senior did not continue in the service, and Their Lordships did not award him with a pension.”

Judge De Lancey laughed, with genuine amusement.

“I see. But what prompted you to—ah—to air the matter here this evening?”

Justin paused to light a fresh cigar. “Oh, I had no intention of doing so initially,” he confessed. “We had intended to bring it up privately, in the commodore’s office, to serve as a warning to the fellow to mind his manners. But this is Red’s farewell, and when Harland deliberately set out to cast a damper on a party we’d all taken a good deal of trouble over, I . . . well, decided that it was an appropriate moment. I trust you will all agree that it was?”

There was a murmur of assent, and Red said gravely, “Thank you, Father. The commodore has not been alone in finding Harland’s attitude a mite hard to stomach.”

His father gestured to the port decanter. “Fill your glasses, my friends,” he invited, “and I will give you another toast before we join the ladies.” They did so, and Justin Broome raised his glass. “To my son-in-law Will De Lancey and to my son John and his wife, who will shortly be leaving us for New Zealand—John is to undertake a report for his newspaper on the land claim problem there. God speed them on their way and, of His mercy, bring them all safely home to us one day!”

They drank the toast, Red taken momentarily by surprise at the news of his brother’s impending departure, and as they left the table together, Johnny told him apologetically, “It’s only just been decided, Red—this afternoon, in fact. We’re going with Will and the boy in the Dolphin.’’ He reddened and added, in a low voice, referring to his wife, “Kit’s not happy here, so I thought—no, dammit, I hope that a change of scene may prove beneficial to her and to our marriage. Unlike you, I don’t seem to be great shakes as a husband, alas!”

Red eyed him with affectionate concern, but Johnny clapped him on the shoulder and managed a wry smile.

“Don’t worry your head about it, brother. It will work out in time, I don’t doubt. But it’s going to be quite a considerable breakup of the family, isn’t it? I’m not so happy about that.”

And neither, Red thought glumly, was he. But that was life; nothing lasted forever, and separations were inevitable. He strode purposefully to his wife’s side, seated himself on the arm of her chair, and put his arm lightly about her slim waist.

“Commander Harland left rather abruptly, Red,” she stated uneasily.

“Yes, my love,” Red agreed. “Thanks to Father, he is liable to be less obnoxious in future.” His arm tightened about her. “Magdalen, I love you! And it’s breaking my heart to have to leave you—you know that, don’t you?”

“Yes,” she answered softly. “I know that, Red. But I’ll follow you. I—I want to be with you always, to the end of my days, my dearest.”

They both looked across, as if by common consent, to where Johnny stood, grim-faced and alone. Kitty Broome, seemingly unaware of her husband’s presence, was talking animatedly to Judge De Lancey, and Magdalen whispered softly, “We are fortunate, Red. Never forget that, will you?”

Red bent to kiss her gently. “No,” he said. “I’ll not forget.”

CHAPTER I

After a largely uneventful passage, accomplished in sixty-nine days, the Galah came to anchor at Spithead. Within twenty-four hours of paying off and taking regretful leave of his ship’s company, Red Broome received a summons to serve as a member of a court-martial, convened on board the battleship Copenhagen, flagship of the vice admiral of the Channel Fleet.

The summons came as a surprise, but at least it was a means of putting off the evil hour when he would be relegated to half pay, plus an indefinite—and, until Magdalen could join him, lonely—wait for fresh employment. Red accepted the summons philosophically, supposing that, as the court was to examine and pass judgement on the loss of a small sloop of war off the Irish coast, the charges would be purely formal and the matter swiftly dealt with. The loss of any Royal Navy ship, whether in war or peace, required that her commander stand trial; but usually—unless cowardice or negligence was proved—the verdict resulted in acquittal, or, at worst, a reprimand or loss of seniority.

This case, however, as he learned when he reported on board the Copenhagen, had more serious implications. The sloop Lancer, of sixteen guns and under sail, had been driven ashore in a gale, with a fire raging on board, and she had gone down with the loss of her captain and all but five of her complement. The officer on trial was her first lieutenant, and Red heard, with some consternation, that his name was Adam Colpoys Vincent.

The Honourable Adam Vincent, a younger son of the Earl of Cheviot—Major General the Earl of Cheviot, who had been one of the Duke of Wellington’s staff at Waterloo. Red frowned as memory stirred. Young Vincent had been an acting lieutenant with the Shannon’s naval brigade, which had served so gallantly in Sir Colin Campbell’s relief of Lucknow during the mutiny, less than two years ago. He himself had been attached to the brigade, and he remembered Adam Vincent well: as a cheerful, courageous young officer, who had been awarded the Victoria Cross as a midshipman, while serving under Captain William Peel—the Shannon’s commander—in the Crimea.

He and Edward Daniel had both won V.C.’s and . . . Red’s frown deepened. He recalled the moving ceremony which, in front of a full-dress parade of the Shannon’s brigade, on their way back to Calcutta, Captain Marten—Peel’s successor in command—had belatedly presented the two young men with their decorations . . . the small bronze crosses, which represented the highest award for gallantry a grateful nation could bestow on its military heroes.

But now one of the same youthful heroes was to stand trial on no less than three serious charges. With the other eleven members of the court, Red was sworn in and, taking his seat to the president’s right, listened to the charges being read by the judge advocate, his incredulity growing as their significance slowly sank in.

Shorn of the legal jargon in which they were couched, the charges amounted to a damning indictment of the young officer’s conduct. Adam Vincent was accused of being in a state of intoxication when—the Lancer’s captain being ill and, in consequence, confined to his cabin—command of the brig-sloop had devolved on him during a severe storm off the southwest coast of Ireland, in the vicinity of Bantry Bay and the Dursey Head light.

Although the sloop was apparently being driven onto a lee shore by gale force winds, evidence to the effect that Vincent had failed to shorten sail in time to prevent this would, the judge advocate stated, be brought before the court. More damning still, it seemed that Lieutenant Vincent, when informed that fire had broken out in the afterpart of the ship, had failed to act with promptitude in dealing with this additional hazard, but had prematurely ordered the ship to be abandoned. As a result of his premature order, the boats in which the ship’s company had attempted to reach the shore had been swamped and capsized, with the loss of 111 lives, including that of the Lancer’s ailing captain, Commander John Omerod.

The final charge, although less serious, astounded Red, for it conflicted completely with the impression he had formed of Adam Vincent’s character during their association in India, when serving in the naval brigade. Vincent, he recalled, had been a reliable and competent officer, with a healthy respect for naval discipline. The late Captain Peel, who had known him longer than anyone else, had held the young acting-lieutenant in high esteem. In one of the last dispatches he had sent to the Admiralty before his tragic death, the Shannon’s captain had recommended him, with several others, for well-merited advancement.

“Indeed,” William Peel had said, “if it were not for the fact that he has already been awarded a Victoria Cross, young Vincent would have been among those whose names I have put forward for the decoration. He does not know what fear is, and he earned the honour twice over at the Shah Nujeef.”

High praise, and yet. . . Red listened in frank bewilderment as, in a flat, unemotional voice, the judge advocate read from the paper in his hand.

“You are further charged that, from five o’clock in the evening until midnight on the tenth day of March of this year, when held under arrest pending your trial by this court, you did absent yourself from the quarters assigned to you on board this ship, and from the custody of the officer appointed to act as your escort, namely Lieutenant Fleming.”

The judge advocate paused, his face set in stern lines beneath the bell-bottomed wig that was the badge of his office. Then, looking across the courtroom to where the accused officer was seated, he invited him to make his plea in answer to the charges.

Adam Vincent responded by rising to his feet. Red had not had a clear view of him until now, and he was shocked by what he saw. Flanked by his counsel, a portly man in a wig and gown, the young lieutenant looked nervous and ill at ease, his face deathly pale and his handsome, fair head bowed. Remembering him as an easygoing, athletic young giant, whom little had ever seemed to deter, Red was startled by the change in him. His reply to the judge advocate’s formal question was inaudible, but before he could be asked to repeat it, the bewigged barrister at his side stated firmly, “The plea is not guilty, sir.”

Vincent held his ground. Recovering some of his lost composure, he drew himself up. “I beg the court’s indulgence, sir,” he requested, in a louder voice. “I wish if you will permit me, to conduct my own defence, sir.”

The president—the Copenhagen’s captain—eyed him with raised brows. “You are entitled to the advice of an attorney, Mr. Vincent,” he pointed out. “And as I understand that learned counsel, in the person of Sir David Murchison, has been retained to advise you, I confess I do not comprehend the reason for your request. Do you not wish to avail yourself of Sir David Murchison’s services?”

Adam Vincent inclined his head. “Precisely, sir. I do not require legal advice, sir. I did not ask for it.”

The president’s brows rose higher. “You would be well advised to think again, Mr. Vincent,” he stated patiently. “You are facing very grave charges, and you are not, I venture to suggest, fully conversant with the law in relation to those charges. In order properly to conduct your defence, and in fairness to yourself, you will need advice. You—”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” Vincent put in, his voice strained, “but Sir David Murchison—that is, learned counsel, sir—we do not see eye to eye in the matter of my defense. I wish to conduct my own case, if you please, sir. To—to question the witnesses on matters with which I am conversant.”

The president glanced, frowning now, at the judge advocate, who offered, not unkindly, “Do you mean that you are desirous of questioning the witnesses, Mr. Vincent? If so, then perhaps I should explain that you are permitted to do so, when you have heard the evidence to which they will testify before the court. Or you may have an officer of your own choosing put questions to them on your behalf, if you do not wish learned counsel to do this. But as the president of the court has told you, the charges against you are exceedingly grave, and it will be in your own best interests if you avail yourself of Sir David Murchison’s expert advice.”

“Thank you, sir,” Adam Vincent acknowledged. “But with respect, sir, I beg the court to allow me to conduct my own defence as—as I see fit, sir.”

The president gave vent to a fairly impatient sigh. The portly barrister, Sir David Murchison, said with asperity, “Then, gentlemen, I will withdraw from the case.” He bowed stiffly to the court and crossed to the two rows of hard-backed chairs reserved for members of the general public. Barely half of these were filled, Red saw, and most of the occupants—judging by the notebooks resting on their knees—were journalists . . . representatives, probably, of local newspapers. But, seated at the end of the back row, a well-dressed, distinguished-looking gentleman of unmistakably military bearing caught and held his gaze. He was white-haired and was, perhaps, in his middle or late fifties, and when the discomfited barrister paused at his side, to engage in a brief, whispered exchange, Red identified the older man as, in all probability, Adam Vincent’s father, the Earl of Cheviot.

Evidently, he thought, the Earl had engaged a leading Queen’s counsel to defend his son, without first obtaining the boy’s permission, and the look of annoyance on his patrician face seemed to lend credence to this supposition. Two or three of the journalists turned in their seats, as if they too had recognized him, and their pencils moved busily as Sir David Murchison, with another stiff bow, gathered his robe about him and left the courtroom, the marine sentry coming to attention as the door swung shut behind the portly barrister.

There was another gentleman of military appearance seated among the reporters in the front row, Red noticed, as his gaze ranged round the small gathering. A few years younger than Lord Cheviot, he was equally well dressed, but he looked less well preserved, his face deeply lined beneath its faint coating of tan, his hair and the heavy cavalry moustache he wore thickly flecked with white . . . a man who had recently recovered from a serious illness, Red decided, wondering, at the same time, what his relationship to young Vincent might be. A friend, perhaps, or an army officer with whom he had made acquaintance in India. The dearth of reporters suggested that the case was not of much interest to the press, but it was possible that, when the Earl of Cheviot’s presence became known, the London dailies would scent the makings of a scandal and send their best men hurrying to Portsmouth, to pick up what they could.

The president had been conferring with the judge advocate, and the members of the court—all strangers to Red—were talking in low voices among themselves; but silence fell when the judge advocate returned to his place. The president, raising his voice, announced that the accused officer’s request would be granted.

“You may conduct your own defence, Mr. Vincent,” he said coldly. “Although I must again advise you that it will not be in your best interests to do so.” When Vincent remained obstinately silent, the Copenhagen’s captain shrugged his epauletted shoulders and, turning to the prosecuting officer, invited him to open his case.

The prosecutor—a commander, wearing the neatly trimmed beard now permitted in the Royal Navy—after a brief preamble addressed to the court, called his first witness.

The witness was sworn and gave his name as Amos Cantwell, third lieutenant of the ill-fated sloop of war Lancer.

He was clearly nervous, and as he replied to the prosecuting officer’s questions in a low, strained voice, he glanced repeatedly towards the officer he was required to give evidence against, as if mutely pleading for his forgiveness. Vincent responded with a singularly warm smile and a nod of the head, and, seemingly encouraged by this, Cantwell became more confident, and his replies, if still almost monosyllabic, were less hesitant.

Skillfully, the bearded prosecutor elicited confirmation of the events set out in the first two charges. The storm had been building all day; by evening, the wind had become southwesterly and risen to gale force. Cantwell gave details of the Lancer’s position; he described how she had battled against mountainous seas, with a strong set to leeward. Captain Omerod had been taken ill very suddenly, the lieutenant testified. He himself had had the last dog watch, and at one bell—six thirty—Lieutenant Vincent had informed him of the captain’s indisposition. The ship, in his own view, had been carrying too much canvas for the prevailing conditions—he supplied brief details, and Red listened with a bewilderment shared by the other members of the court, all of them aware that prudence would have dictated an order to shorten sail.

“You received no such order, Mr. Cantwell?” the prosecuting officer demanded.

Cantwell shook his head. Reluctantly, in reply to a series of questions, he admitted that both he and the officer he had relieved at the end of the first dog watch, the Lancer’s second lieutenant, had requested permission to take in sail.

“The first lieutenant said that the captain had refused permission, sir. He went below, after I made my request, sir, to speak to Captain Omerod. Then, when he returned to the deck, sir, he informed me that the captain had been taken ill and that he was in command. It was then he gave the order to take in sail. ”

“Lieutenatn Vincent gave the order?”

“Yes, sir, he did.” Amos Cantwell hesitated, stealing another, anxious glance at Vincent. Receiving another nod, he went on. “The topmen were—well, they were scared, sir. We were carrying a number of raw hands, and going aloft in such a wind was bound to be risky. Mr. Vincent swore at them, sir, and said he’d show them how.”

“And did he?”

“Oh, yes, sir. He kicked off his seaboots, and he and the captain of the maintop, Petty Officer Kay, went up together. The other men followed them.” Once launched on his description, Cantwell recounted events with eagerness, displaying considerable admiration for Vincent’s conduct.

The bearded prosecutor brought him abruptly back to earth. “At the time, Mr. Cantwell, was the first lieutenant completely sober?”

“Sober, sir?”

“Yes, sober, Mr. Cantwell. You said in your deposition that he appeared to be unsteady and that you caught the whiff of spirits on his breath. You said you thought he had taken a drink with the captain, did you not?”

“Well, yes, sir,” Cantwell conceded unhappily. “It was a very rough night, cold and—well, I’d have taken a drink, sir, if I’d been offered one. Mr. Vincent ordered a tot of rum for the topmen, after they came back on deck. He said they deserved it, sir. And he had a tot himself—he was soaked to the skin, sir, and freezing cold. They all were. And one man—a new rating, Ordinary Seaman Bowman, who’s one of the witnesses, sir—he slipped from the main shrouds, when he was about eight feet from the deck. Luckily for him, he landed on a heap of canvas, sir, and wasn’t badly hurt. His shoulder was dislocated, and the first lieutenant ordered him a double tot and then put it back for him, sir. His shoulder, I mean, and—”

The prosecutor cut him short. “Yes, yes, we shall hear from Ordinary Seaman Bowman in due course. What I am trying to ascertain and what this court wants to know is Lieutenant Vincent’s state of sobriety when he came on deck, after visiting Captain Omerod in his cabin. Was he in fact drunk, Mr. Cantwell?”

“I—I can’t say, sir.” Cantwell reddened.

“You must say. You are on oath, Mr. Cantwell.”

Again the young officer looked across at Vincent uncertainly, and once again he was given a reassuring nod.

“I . . . sir, I supposed that he had taken a drink with the captain. But he wasn’t drunk, sir. He knew what he was about, and the ship was pitching heavily. None of us were able to move steadily on deck, sir.”

“Very well, Mr. Cantwell,” the prosecutor acknowledged. “I will leave it to the court to judge. Let us go on to the circumstances in which your ship was abandoned.”

“That was much later, sir,” Cantwell supplied, clearly pleased to be asked no more questions concerning Vincent’s sobriety. “After the fire, sir.” With reasonable fluency, he described how, having gone below at the end of his watch, leaving Vincent in command of the first watch, he had been roused from sleep by shouts of alarm and the pipe summoning the watch below to turn up.

“We all turned up, sir. It was six bells of the middle watch and Mr. Rayburn had the deck, but the first lieutenant was there too. He said that a fire had broken out below. He didn’t say where, sir, but Mr. Rayburn told me it was in the captain’s cabin. Mr. Vincent called for hoses to be rigged, and he went below with a fire party. I stayed on deck, sir. I could see we were dangerously close to the shore—the Dursey Head light was clearly visible.” In graphic detail, Amos Cantwell described the frantic efforts the Lancer’s crew had made to claw her off the rocky shore. “Mr. Vincent had ordered the forecourse set, but wind and tide were too strong, sir. We had two good men on the wheel, and I went to help them, but she wouldn’t answer to her helm. Mr. Rayburn told me that they’d been fighting a losing battle for half the night, and the fire was just about the last straw. Then the first lieutenant came back on deck, sir. He said he would try to bring her about and clear the Dursey Head . . . .” Cantwell talked on, needing no prompting now, and Red imagined himself in a similar predicament, certain in his own mind that he would have done exactly what Adam Vincent had done, given the circumstances in which the Lancer’s unfortunate first lieutenant had found himself.

“We were bringing her head round, sir—or I thought we were,” Cantwell said hoarsely. “But then she shipped a ton or two of water and was thrown on her beam ends. She seemed to hang there for—oh, for an age, sir, and then she righted herself. And then—” He broke off, his young face suddenly draining of colour. “Mr. Vincent sent me below, to take charge of the fire party. I saw the captain come on deck—Mr. Lee and a seaman were assisting him, and he looked very ill, sir, barely able to stand. I—that is, I’d only just found the fire party when the order was given to—to abandon ship.”

“Who gave the order, Mr. Cantwell?” the president asked sharply.

Cantwell turned to face him. “I don’t know, sir.”

“What do you mean, you don’t know?”

“I only heard it repeated, sir. I ordered the fire party to obey it, and they didn’t waste any time. They went on deck at once, sir.”

“But you did not?” the president pursued, after consulting a sheaf of papers on the table in front of him. “Why not, Mr. Cantwell?”

Cantwell stiffened. “I stayed to make certain that no one was left below, sir. The cook had been badly scalded earlier on, and I knew he was in the sick bay. And there was Ordinary Seaman Bowman—he had been sent there, after his fall from the shrouds, and he’d been given a dose of laudanum. I thought that probably they wouldn’t have heard the order, you see, sir.”

“And hadn’t they?” the president demanded, frowning.

“No, sir,” Cantwell answered. “And neither had our passenger, Lieutenant Lane of the Royal Marines, sir. I found him in his cabin—he said he’d been asleep all throughout the storm, sir. And . . . I ran into the first lieutenant in the sick bay. He had come on the same errand as myself, you see, sir.”

“I see.” The president nodded to the prosecutor, who concluded the questioning with a crisp invitation to the witness to describe what had next occurred.

Cantwell’s young face seemed suddenly to age.

“I helped Mr. Vincent to take the two men from the sick bay on deck, sir. Lieutenant Lane had gone ahead of us, and he—sir, I heard him cry out, ‘They’ve gone down, the lot of them! The boats have been swamped!’ And when I reached the deck I—I saw that he was right. It was hard to pick out with such a sea running, but I saw the whaler turn right over, spilling her crew into the water. There were heads bobbing about, but . . . they didn’t last long, and there was nothing we could do to help them, sir. There was only one boat left on board the ship—the gig, sir, but the sea had stove it in. We—we just had to watch them drown.”

“You have our sympathy, Mr. Cantwell,” the president said, with gruff kindness. “It must have been a terrible sight.”

“Yes, sir, it was,” Amos Cantwell confirmed bleakly. He shivered and, after another glance at Lieutenant Vincent, added in a whisper, “I—I wish I could forget it, sir.” He braced himself and, sensing that his ordeal was almost over, spoke in a louder tone, “The ship was driven ashore about—oh, about two hours later, sir, and the people in the lighthouse had seen our plight, and they helped us swim ashore. Even so, sir, I was nearly swept away. The first lieutenant, Mr. Vincent, saved my life—he held on to me, and then he went back for Bowman, who couldn’t swim. He—Mr. Vincent shouldn’t be on trial, sir. He—”

“That,” the president interrupted sternly, “is not for you to judge, Lieutenant Cantwell.” He sighed audibly and then addressed the accused officer. “Do you wish to cross-examine this witness, Mr. Vincent?”

Vincent rose. “No, sir, thank you. Mr. Cantwell has given his evidence admirably. I question nothing he has said, sir.”

The president glanced inquiringly to either side of him. “Gentlemen? Have you any questions to put to Mr. Cantwell?”

Only one member of the court—a thin-faced, elderly commander—availed himself of the invitation. For almost ten minutes he tried aggressively to browbeat Amos Cantwell into admitting that the Lancer’s first lieutenant had been drunk. He failed in this endeavour, but Vincent looked flushed and angry when, at last, the commander abandoned his questioning and allowed the witness to be dismissed.

The next witness, however, had the commander smiling in unconcealed satisfaction. He was in Royal Marine uniform, a short, stout individual with iron-gray hair and the faint suggestion of a Cockney accent—a long-serving ranker, Red decided, whose career had suffered from lack of education.

Giving his name as Thomas Arthur Lane and his rank as lieutenant, he bore out, in substance, much of young Cantwell’s evidence, while admitting that he had slept throughout the worst part of the storm.

“Seein’ I was a passenger, sir, with no duties to perform, and as it was certain sure we was in for a rough night, I got me head down in me cabin. But Captain Omerod’s cabin wasn’t far away—in earshot, if anyone there raised his voice. And they did, sir—him an’ the first lieutenant. At it hammer an’ tongs, they were, the pair of them.”

“Do you mean, sir” the prosecutor asked, “that you heard the captain and the first lieutenant engaged in some sort of altercation?”

“It was more than an altercation, sir—more like a quarrel,” the marine officer asserted with conviction. “I couldn’t hear what was being said, you understand, but I didn’t have to, not in order to know that they were far from being in agreement. Shouting at Lieutenant Vincent, the captain was, calling him names, as nearly as I could judge. I did catch a word or two, but not enough to say what they were quarrelling about.” Becoming conscious of the rapt interest of the entire courtroom in his testimony, Lane paused, his thin lips curving into a mirthless smile. “I did hear Mr. Vincent say that the ship would be in trouble if they didn’t shorten sail. And the captain told him to be damned. ‘I’ll take in sail when it’s necessary,’ he said.”

“Did you hear any more?” the prosecuting officer prompted.

Lane shook his head. “No, sir, because they stopped. I heard the first lieutenant leave the captain’s cabin, and I went to try to intercept him, intending to ask him what was going on. But he just brushed past me without giving me an answer.”

“Did you—think carefully, Mr. Lane—did you form any opinion as to Mr. Vincent’s state of sobriety?”

“He was drunk, sir,” the marine officer answered without hesitation. “Stumbling and staggering, and he was reeking of liquor. Besides that, his speech was slurred.”

The president intervened. “I thought you said that Mr. Vincent did not speak to you when you endeavoured to accost him?”