Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Skinnbok

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

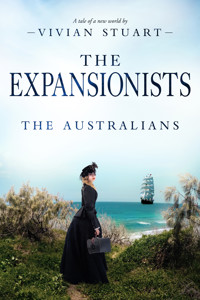

- Serie: The Australians

- Sprache: Englisch

The twenty-fourth, and final, book in the dramatic and intriguing story about the colonisation of Australia: a country made of blood, passion, and dreams. Finally the end has been reached as the Australians look towards the future. The Australians have reached a time of technological advance that features steam power of ships and auto mobiles becoming the preferable personal transportation for the wealthy Australians. Australia becomes Australia as we know it today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 385

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Expansionists

The Australians 24 – The Expansionists

© Vivian Stuart, 1990

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2023

Series: The Australians

Title: The Expansionists

Title number: 24

ISBN: 978-9979-64-249-7

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

The Australians

The ExilesThe PrisonersThe SettlersThe NewcomersThe TraitorsThe RebelsThe ExplorersThe TravellersThe AdventurersThe WarriorsThe ColonistsThe PioneersThe Gold SeekersThe OpportunistsThe PatriotsThe PartisansThe Empire BuildersThe Road BuildersThe SeafarersThe MarinersThe NationalistsThe LoyalistsThe ImperialistsThe ExpansionistsChapter I

When sudden storms bring torrential rains to a desert area, such as the Gibson in Western Australia, the water pools atop the powder-dry soil. It is an odd phenomenon with which every gardener is familiar: The drier the soil, the greater the runoff of water. The arid dust forms a barrier to the penetration of moisture, so that the rains form muddy rivulets that pour into the erosion gullies and finally into ancient dry streambeds — like the wash beside which Tolo Mason had set up camp on the evening that brought the animosity between him and Terry Forrest to a head.

Desert rain is an example of too much of a good thing too quickly. The bloated clouds burst with spectacular displays of lightning, with cannonades of thunder, and the dry desert gasps with thirst; but at first the ground perversely rejects the gift of water. Thousands of rivulets drain into the wash, and a flash flood is the result. Countless tons of water fill the wash from bank to bank and rush toward the sea. The leading edge of the head rise is a shallow, roiling extension of the thundering wave, like a cow catcher on a locomotive. Quickly behind the advance ripple comes the vertical wall of water, cresting at the top, carrying driftwood, uprooted brush and grass, even the dead bodies of unwary desert animals. The advancing flood, bearing everything in its path, moves faster than a man can run.

Terry Forrest had seen flash floods, but never from directly in front of the advancing wall of debris-filled water. He was exhausted from his long, battering fight with Tolo Mason, and his brain was numbed. When he first saw the wave, it took precious seconds for him to realize what was happening. He tried to stand, but his legs collapsed under him.

Tolo, too, had seen the onrushing water. He took a few steps toward the bank. He had just enough time to make it.

“Help me, mate,” Terry Forrest called out.

Tolo hesitated but a moment, then ran back, lifted Forrest with his hands under his arms, and started dragging him toward the bank, which seemed now to be miles away. Tolo, too, drained by the bruising fight with Forrest, was not at his best, and his arms ached with the weight of the man. His lungs burned with his efforts, and the thundering water came closer, closer. When the first ripples lapped at his boots, he knew that they were not going to reach the bank. The cresting front of the flood was only feet away. He threw himself down, thinking that their best chance of survival was to let the crest of the wave fall over them and pass them by. In those few seconds he knew that if they were to be caught up in the debris that churned on the brunt of the wave, they would be ground up and broken, tossed and twisted, appearing and disappearing on the waters like the carcass of the dead kangaroo that seemed to launch itself directly at him.

The water crashed into them. Tolo had taken a deep, deep breath. He tried to cling to the bed of the wash, but the force was too great. Tumbled over, he felt the dull blows of collision with things.

Terry Forrest was holding on to him with the force of sheer panic, and at first that helped, for their combined weight acted as a drag, allowing the deadly crest to pass them. But then Forrest became a dangerous burden.

Tolo reached down, put his hand in the man’s hair, and pulled hard. Slapping at Forrest’s hands, which clutched him around the waist, he loosened Forrest’s grip, then kicked upward, pulling Forrest with him. They were being swirled downstream, carried by the force of the flood. When Tolo’s lungs began to bum, he feared that they were not going to survive. He was kicking powerfully, dragging Forrest. And then his head broke the surface, and he took a gasping breath that was partially spray; he coughed it out and dragged a rasping lungful of air through the pain of water in his lungs.

Beside him Forrest was floundering, and Tolo almost lost his grip on the man’s hair. Unable to speak because of the inhaled water, Tolo gasped and coughed again, his inhalations nothing but painful, choking spasms. And then, at last, he spit out water and could breathe freely. Forrest was making odd sounds and rolling over and over, trying to get his hands on Tolo. As the current rushed them farther downstream, floating brush and drift smacked against them, sometimes sticking painful spines into their flesh.

Forrest managed to turn and with one arm clasped Tolo. Tolo knew that although the motivation was different now, he was still in a fight with Forrest, this time a fight for their lives, for if the man managed to get his arms around Tolo and immobilize Tolo’s arms, both of them would drown. He sighted in a blow, gave it all he had, and cracked his fist into Forrest’s jaw just to one side of the chin. Forrest went limp and ceased struggling. Tolo turned onto his back and began to kick toward the bank. Forrest, now inert, floated easily as Tolo pulled him along.

The water was cold, and it cleared Tolo’s head; but having to dodge heavy floating objects, he found his strength rapidly giving way. Alone, he could reach the bank, but with Forrest in tow, he wasn’t so sure. And yet he clung to the man’s hair, fought the swift current, and angled slowly, slowly toward the bank.

When he finally reached the bank, the current continued to drag him downstream for some time until he managed to grasp a mulga tree. He clung there for long minutes, one hand on the plant, the other holding Forrest, until both of his arms began to ache. Little by little he drew himself up until he was out of the water, then hauled Forrest up and rolled him onto his back. Forrest was not breathing. Tolo began to push rhythmically just below the man’s diaphragm, and after what seemed an impossibly long time, Forrest gagged and vomited up water and began to gasp for breath.

Tolo fell onto his back and slept.

He awoke in the cold, shivering uncontrollably. Rising, he gathered material for a fire, then pulled his matches from their waterproof carrier. Soon he had a blaze going. He checked Forrest and saw that his eyes were open.

“You pulled me out,” Forrest said accusingly.

Tolo turned his back and tended his fire.

“Owe you one, mate,” Terry said.

With the first light of dawn Tolo was on his feet. “Can you walk?” he asked Forrest.

“Can a kangaroo hop?” the bushranger answered. But as he tried to get to his feet, he cried out in pain and fell back.

“Well, I thought I was in one piece,” he said.

Tolo knelt beside Forrest and pulled up the man’s pants leg carefully. The calf muscle was swollen to twice its normal size and was one huge mass of lividity.

“Looks as if something hit you quite a lick,” Tolo said.

“Damn,” Forrest said, fingering the bruised area gently. “What with all the spinifex spines in my hide, itching and burning, I guess I didn’t feel it until I tried to put my weight on it.”

“I suspect that Java will ride downstream looking for us,” Tolo said.

“I hope she has enough smarts to refill the water barrels before the desert sucks it all up,” Forrest said. The flood had passed, and by now only a trickle of water ran down the centre of the wash, but there was still water in deeper rocky basins.

“How far do you think we were carried?” Forrest asked.

“Hard to say,” Tolo said.

“I couldn’t make a guess,” Forrest said. “Seems I was out of it, doesn’t it?”

“Yes,” Tolo agreed.

“You know I don’t swim, mate.”

“I guessed as much,” Tolo said.

“You didn’t have to pull me out, did you?”

“I’m not sure you’ll understand, but yes, I had to pull you out, or at least I had to try.”

The sun rose, bathing the featureless plain in a red glow. They were on the opposite side of the river from where Tolo had pitched camp. Tolo helped Forrest down to the wash, where they drank deeply from a billabong and then took off their clothing to bathe and rinse the sand from their garments. The flood had half filled their pockets with the red dirt of the Gibson.

As the heat of the day came on in full force, they found a bit of shade under the bank of the wash and waited.

The fever came to Forrest with a suddenness that made Tolo fear for the man’s life. One minute Terry was lying there sweating in the heat, chewing on a twig, and the next he was red-faced, burning with heat. Then a chill came and his teeth chattered.

Throughout the rest of the day and through a long, almost sleepless night Tolo did what he could, which was little. When Forrest burned with fever, he could cool his brow with water from the billabong. When the racking chills came, he could only put more driftwood on the fire. He wanted to go to Java, knew that she must be frantic with worry, but aside from that, he felt that she was safe. She had the guns. He could not understand why Java had not found them during the day, for by his wildest estimate he could not have been carried more than a few miles by the flood. But she’d show up tomorrow, and then they could dose Forrest with quinine or something.

After another day the fever abated; leaving Terry very weak. There was plenty of water, but no food. Tolo kept his eyes open for the approach of Java and the camels, but nothing moved but the dancing heat waves. As evening approached, he told Forrest, “We’re going to have to go to them, you know.”

“Give me a hand up,” Terry replied. “Maybe we can make it to the next billabong before it gets too dark.”

Walking was painful for Terry, because of both his injured leg and the residual effects of the fever. He explained that he had contracted malaria on a gold-hunting trip into the Northern Territory, and the immersion and battering in the flood had apparently triggered a recurrence.

As he assisted the bushranger, Tolo found that his attitude toward him had shifted slightly. The man had been damned cheeky, but he had pluck. And Tolo, after pulling him from the flood and nursing him through his fever, felt yoked to the man by the code of mateship in the bush. The elements had conspired to join them, for the time being at least, regardless of whether Tolo liked it or not.

It was almost dark when they reached the next water hole. “A mob of boongs made camp here,” Terry observed. In the fading light he could just see the signs. Then they found the site of the fires.

“Ganba?” Tolo asked.

“Most likely. The boongs don’t come into the heart of the Gibson too often.”

Tolo scouted the banks and then helped Terry up when he found camel tracks on both banks leading away from the wash. Terry bent to examine the prints.

“Wild camels or ours?” Tolo asked.

“This one was carrying a load,” Terry said. “See how the mark of the hoof splays out?”

“So Java came downstream looking for us and ran into Ganba?”

“Looks that way,” Terry said. “No worries, mate. Ganba is a scoundrel but no fool. He’d steal the fillings out of your teeth, given the chance, but he wouldn’t have the guts to harm a whitefellow woman.”

Tolo was remembering that he had been warned more than once about becoming meat food for the Aborigines.

“My guess is, mate, that he’ll go on just as before. He’ll lead her on a merry chase around the bloody desert, hoping that the Gibson and the sun will kark her off. We’ll catch up to them long before that.”

They made a fire in the wash near the water hole. The water, Tolo knew, would be gone soon, evaporated by the sun or sucked into the rocky bed of the wash. In the meantime, both he and Terry would make the most of it.

“They had meat,” Terry said. There was a lingering smell of it that both men caught.

“Where would they get meat?” Tolo asked.

“Rabbit. Wild camel,” Terry said. The smell was quite strong. He sniffed, followed his nose, and saw a bit of white protruding from the sand of the wash. Digging around the bone, he lifted it out. It was a human thighbone. He threw it as far as he could in total disgust.

“Bloody—” He could not finish.

Tolo recovered the bone. His face flushed with fear when he recognized what it was.

“It isn’t the little sheila,” Terry said. “Notice the curve of the bone. Poor bastard had rickets or something.”

“Surely not in this day and time,” Tolo stammered. He felt his stomach twist. He buried the bone with his hands and pressed the sand down on it. “Surely they don’t still—”

“Bloody hell,” Terry said. “Of course, they do. Damn boongs. What we should do is hunt them off the face of the earth.”

“She’s with them,” Tolo said. “She must have seen—”

Terry was moving around painfully. He had found a mulga stick that served him as a cane to take some of the weight off his injured leg. “She started toward the west,” he said, examining the ground. “One Abo followed her. And then the tracks come back, cross the wash, and head off north. She was going to head for Mayhew’s station, and Ganba talked her out of it. He’s leading her off toward the north.”

“Look here,” Tolo said, “I’m going to have to go on ahead in the morning. I can move much faster than you. You stay here with the water, and when I catch them, I’ll come back for you.”

“The water here won’t last another day,” Terry said. “I’d better come with you. Sure, you can move faster than I can, but you won’t last long on your own.”

“And how would we last longer with you along?”

“Bush tucker,” Terry replied. “I’ll wager your boongs didn’t teach you how to survive out here, since I figure old Ganba’s whole purpose was to see you dead.”

“I know only what I’ve read,” Tolo admitted.

“Well, there are little things — roots of the potato family. Some of them will kill you within hours if you take one bite, but others are edible and have just enough moisture to keep you alive a little longer.” He patted his injured leg. “It’s already better. Sore as bloody hell, but better.”

“All right, then,” Tolo agreed.

They were Under way with first light. The trail was easy to follow. “We have three or four days to catch up with them,” Terry said. “After that—”

“What do you mean?” Tolo asked.

Terry bent, dug with his walking stick, and held up a tuber. “You can get some nourishment and about a tablespoon of water out of this, mate. If we’re lucky, we’ll find one or two of them a day. Two tablespoons of water. Enough to keep a man going two, maybe three days.”

“I see,” Tolo said. “Then we’d best move out, hadn’t we?”

When they came upon the dead camels, Terry used a colourful portion of his vocabulary. “A damn waste,” he said. “That’s a bloody boong for you. Fill his belly and he has no concern for tomorrow.” He had shooed away the carrion birds and was working on the carcass with his knife. He cut away the outside rot, the pecked and pierced areas, and ripped out a long muscle from the haunch.

“You’re not going to eat that?” Tolo asked.

“No? Just stand and watch,” Terry said. He built a fire and cooked the meat in thin strips, so that it was thoroughly heated, almost burned. And with his mouth watering, Tolo ate his share, blocking out the taste, knowing only that his body was desperate for food.

“We’ll catch them tomorrow,” Terry said. He was leaning against a boulder, his bare feet near the fire. He was chewing on the well-cooked camel meat. “They’re near. I can almost smell them.”

The rain came during the night, obliterating the trail. The next morning Tolo led the way northward in desperation, moving at a punishing pace.

They heard the Abos before they saw them. From behind a low ridge the chanting voices came, indistinguishable at times from a sigh of wind that blew out of the storm clouds to the east.

It was Terry who led the way up the slope, covering the last few yards on his belly as Tolo crawled up beside him.

The Abos were camped beside a soak; a hunk of camel meat was roasting over a fire. There was no sign of Java.

Terry punched Tolo in the shoulder and pointed. Ganba was leading the dance and the chant, and as he pranced around the fire, thumping his bare feet onto the ground with audible thuds, he held Tolo’s rifle in his hand.

“There are only five of them,” Tolo whispered. “And Ganba’s wife, Bildana, is not among them.”

Aside from Ganba, there were two men and two women. The women were huddled beside a fire of their own, watching the prancing, chanting men nervously.

“First thing to do is get that rifle away from him,” Terry whispered.

“But where is Java?” Tolo asked. The camels were dead. The water barrels were empty, scattered along the back trail.

“Well, mate, I reckon we’ll have to ask old Ganba about that, won’t we?” Terry asked. He motioned to Tolo to crawl back from the crest of the ridge. They found cover in a swale that was filled with spinifex grass, where they waited until the sun had set and the cold night was on them; then they crawled back to the top of the ridge. The Abos were feasting on camel meat and drinking water from waterskins.

It was a long, cold wait until the camp was silent, the fires burned down to embers. Ganba slept with one of the women at the far edge of the camp. Terry led the way, and the two men circled far out, then came up on the camp from the side nearest Ganba. Now and then, when Terry’s foot slipped on a stone, he would grunt in pain.

“You,” he whispered to Tolo when they were near the camp. He pointed, made a motion as if aiming a rifle.

Tolo crept forward on his hands and knees, making each move slow, feeling the ground to be sure he did not make a noise. As he moved closer to Ganba, who was sleeping in two of Tolo’s blankets, the rifle clasped in one hand, Tolo rose to his feet, reached down slowly, grasped the rifle, and yanked. The weapon came free. Ganba, with surprising speed, jumped up out of the blankets. Swinging the rifle by reflex, Tolo caught Ganba in the chin with the butt and sent the Abo tumbling backward.

Terry had moved up. He saw Ganba fall and then roll toward the blankets. He saw Ganba’s intention. The pistol was in its holster, lying beside Ganba’s kip. Terry leapt, grunted in pain, fell, then grabbed the pistol just before Ganba’s hand closed over it.

“Enough,” Terry said, pointing the pistol at Ganba’s face and thumbing back the hammer.

Tolo heard a noise behind him. He whirled just in time to see one of the Abo men launch a spear. He ducked and lifted the rifle. He pulled the trigger without thinking, and the Abo was thrust backward as the slug took him high in the chest.

A spear grazed Terry’s head. He snapped off a shot with the pistol and the other Abo man was down.

A woman screamed. Ganba, dazed, had the fear of death on his face as Tolo stood over him. “Where is she?” Tolo demanded.

Ganba shrugged.

“Do I kill the bloody bastard or do you?” Terry asked.

Ganba looked from one man to the other, clearly grasping the reality of the whitefella’s threat. “She left,” he said quickly, pressing his hands together imploringly. “In the rain, I tell you. She and my faithless wife. I swear to you, young master, I did her no harm. I had explained to her that the nearest water was to the north—”

“He lies,” Terry said.

“Ganba was protecting her, young master.” The big mouth was contorted in fear, the dark eyes wide. “I did not touch her. Why she ran away I do not know.”

“Did she have water?” Terry asked.

“Yes,” Ganba said. “And food.”

“Do you know which way she went?” Terry asked.

“I have seen no spoor,” Ganba said. “But once she tried to go to the west, toward Mayhew Station.”

Terry let the pistol fall. “He’s probably telling the truth,” he said. “If she and the boong woman did get away, they’d head for Mayhew’s. We’ll have some of this lad’s tucker and borrow a waterskin or two and go after her in the morning.”

“Ganba will help.”

“Ganba can bloody well get as far away from me as possible,” Tolo said. “Why in God’s name did you kill all the camels?”

“We needed meat food,” the Aborigine said, as if Tolo’s question were utterly foolish.

“We saw what was left of some of your meat food,” Terry said. He put the pistol in his belt and went to the fire, sawed off a piece of camel meat, and was taking the first bite when he heard Tolo grunt, as if in surprise. He turned quickly.

The spear that protruded from Tolo’s back had been put there by one of the women. She had seen her man fall before Tolo’s rifle and had waited for her opportunity. A strong woman, she had been standing close, and she had not thrown the spear but rather had thrust it into the whitefella’s back on the run. Her aim had been thrown off at the last minute as Tolo moved, so that instead of striking him directly in the spine she had pierced Tolo’s side low and to the left. As Terry Forrest turned to look, Tolo put one hand behind him, clasped the spear, looked at Terry in puzzlement, and sank to his knees.

Terry hesitated only a moment before shooting the woman in the head. She crumpled lifelessly. The other woman started to run, and it took two shots to bring her down. And then he turned the pistol on Ganba.

In that split second a look of surprise crossed Ganba’s face, as if he had thought that he, the proud Ganba, was invincible. Then the slug from Terry’s pistol took him on the bridge of the nose and slammed into his brain.

Terry knelt beside the fallen Tolo. The spear had penetrated deeply, the entire head of it buried in flesh. Tolo was breathing. His eyes were open but glazed with shock. Terry guessed that the spear had ruined a kidney.

“Well, sport,” Terry said, at a loss for words.

“I don’t feel anything,” Tolo replied.

“There’s a bloody great spear in your back, mate.”

Tolo began, then, to feel the pain. His face contorted with it.

Terry sighed. “Well, I guess we’ll have to have a go at getting it out.”

He spread one of the blankets that Ganba had stolen and shifted Tolo onto it. Tolo cried out in agony.

“Sorry, mate,” Terry said.

He built up the fire. He found one of the things he needed, a large broad-bladed knife, on one of the dead Abo men and placed it to heat in the embers of the fire. When the fire was blazing well, he took a look at the entry point of the spear and whistled.

“Going to smart a bit, mate,” he said as he sliced with his knife.

Tolo let out a startled bellow of pain and then went limp. “Goodonyer,” Terry said. “Won’t feel a thing now, mate.”

When the spearhead came out, a gush of blood came with it. Terry shook his head. Too much blood. He positioned the large, flat blade of the Abo’s knife — now white hot — over the wound and pressed it down. He heard the sizzle of heat, smelled the stench of scorched blood and flesh, but after a while the blood stopped flowing. He lifted the knife, examined the cauterized wound, and shook his head. He had done all he could do, so he covered Tolo with the other blanket and went to sleep.

When Terry awoke, Tolo was feverish. Flies had found the blood of the dead boongs, and soon this place would stink to high heaven. Terry took inventory, finding a few tins of food, some lentils and rice, and two waterskins. It might be just enough to get him back to Mayhew’s alive, he thought, if it did not take Tolo too long to die.

He had a tin of fruit for breakfast and poured a bit of the juice into Tolo’s mouth. Tolo swallowed convulsively. Later he took water but remained in a feverish coma. The carrion birds were working on the woman who lay furthermost from the camp.

“Look, mate,” Terry said to the unconscious Tolo, “be a pal and kark it in, won’t you? It’s a bloody long walk back to the Gascoyne.”

By evening the bodies of the Abos had swelled up with the gases of decay. Tolo had not regained consciousness.

“Come on now, mate,” Terry begged. The scent of death was in his nose. The thought of spending a night there in that camp with the dead spread around him was a frightening prospect. Ganba’s body lay only feet away, and even as Terry contemplated the long night ahead, gases roiled in Ganba’s bloated stomach, and there came the long, sighing sound of breaking wind.

“Bloody hell,” Terry said, leaping to his feet. He looked down at Tolo. “Sorry, mate,” he said.

On impulse he left one of the waterskins. It was a damned foolish thing. “The least I can do,” he whispered as he turned his back and fled that place of rumbling corpses and stench. He almost went back for the water. Tolo would have no need of it. Even if he regained consciousness and drank it, it would merely hasten his death, what with one kidney ruined inside him.

He walked as fast as his lame leg would allow, putting distance between him and the scene of the deaths. He carried both the rifle and the pistol as well as the remaining food. Walking until the stars of morning were visible, he slept a few winks and then was moving again with the dawn. Even with his experience in the waly, there was no guarantee that he would see Mayhew Station alive.

Chapter II

The second wave of human invasion of the antipodal continent, those Caucasians who were, early in the twentieth century, developing the finishing touches on their unique national character, had borrowed a few things from those who had come to Australia before them. They had taken place-names: Toowoomba, Penong, Kalgoorlie, Meekatharra. Also the often musical sounds of Aboriginal names for animals — wallaroos and bandicoots. There were other miscellaneous words, too, like billabong and coolabah. And walkabout.

White bushmen had adopted both the term walkabout and the urge, but explorers and those who followed in their footsteps into the heart of the continent travelled for reasons very different from those that drove the Aborigines to walkabout. The white man went in search of gold, land, adventure, or simply to see what lay beyond the next rise of arid ground. The Aborigine, caught in the old life pattern of the hunter-gatherer, went walkabout when game became scarce or when native vegetation was consumed or burned by drought. He had been on the move for hundreds of thousands of years, and the pattern was ingrained in him. Accordingly, “tamed” Abos, earning what was for them a good life working on a cattle station, would disappear at unpredictable intervals and, upon return, would simple shrug and say, “Walkabout.”

While the principal motivation for being nomadic was the eternal quest for food, other motives could drive an Aborigine and his tribal group from one place to another: the need, for example, to visit some particularly sacred place — a body of water, or a hill, or a rock that had significance from the time of the Dreaming. There was an interrelationship between the blackfellow and the land, for the Aborigine believed in the oneness of things: He was of the land, and the land was of him. He and the rocks, the waters, and the trees — all were joined. Those mysterious beings of the ancient Dreamtime, those undefined entities that had made the first men, were still there in the land, embodied in things of nature — in the animals, the rain, the clouds. And the presence of one of those powerful entities made a place sacred.

Thus it was, even before the time of the coming of the white man’s ships, that men were called to go walkabout, not only to find new sources of food but to pay tribute to places made sacred by the wisdom of their own tribe or another tribal group. Before the white man’s law was extended to most parts of the continent, travel between tribal areas had been limited and rather dangerous. But in more recent times Aborigines could travel more freely, sometimes indeed attaching themselves to the peripatetic white man, who seemed bent on exploring all parts of the continent. Thus knowledge of the sacred places was spread into the homelands and languages of almost all the Aboriginal tribes, and the impulse to go walkabout could result in a very long journey, to a place hundreds of miles away. Aborigines became like Christians on pilgrimage to Jerusalem or Moslems travelling to Mecca. And of all the sites sought by tribes all over the continent, the great-red-sacred-rock, known to the whites as Ayers Rock, in the southwest comer of the Northern Territory, held the greatest allure.

The knowledge of this sacred rock had reached Uwa — a man of high degree among his people — in his tribal lands near the great western sea, in the hills called by the whitefella the Hamersley Range. Even when Uwa had first heard of the great-red-sacred-rock, where, it was said, one could return to the spirit of the Dreamtime and learn from the ancients, he was not a young man. As he prepared for the greatest journey of his life, his several wives and all of his offspring wept and begged him not to go to his death in the arid stretches of the never-never. Young men could cross the burning, waterless vastness, but Uwa was old.

As it turned out, Uwa proved himself as vigorous as any man when it came to living in the never-never. As a young man, while accumulating the wisdom that would elevate him to a man of high degree, he had travelled far and wide, and now his experience served him well. Crossing the never-never, he set a pace that stretched the physical abilities of the younger ones whom he had recruited to accompany him. He conquered the Gibson Desert — although he did not use the whitefella’s name for it — with no suffering to himself and without losing a single man or a woman.

In the far lands near the great-red-sacred-rock Uwa meditated and communicated with other men of high degree, men belonging to the tribes of what the whitefella called the Northern Territory. He tranced himself into seeing the entities that flocked over the huge red rock and saw his number one grandson take a wife from the Northern Territory tribes.

When, on the return trip, Uwa and his small band of half a dozen little families — babies had been born during the pilgrimage — paused to praise the spirits for the rain that had come to give them much-needed water, they had recrossed two-thirds of the never-never and could begin to think of arriving at their home territory before the next full moon.

While the women and the young ones played in the rockbottomed billabongs left in the wash, Uwa and two of the younger men hunted. It was not the best of hunting grounds, but Uwa proved his worth by bagging a rabbit. Then he saw the tracks of a lone dingo and followed them. It was growing hot, the sun moving toward its zenith, when he first noted the soaring carrion birds at a distance. Curiosity led him onward. He hoped that perhaps some accident had befallen a wild camel and that he could steal edible meat from the scavengers before it spoiled too badly. But that hope faded when his nose caught the unmistakable stench of rotting flesh.

He topped a rise and looked down upon a place of the dead. The two young men who had been hunting apart from him now joined him, and they, too, stood watching the birds fight over the already mutilated bodies of no fewer than five people — three men and two women. Uwa gave orders, and the two young men ran down the slope, shouting and brandishing their spears. Then Uwa walked curiously among the dead. All of them, including the women, had died of gunshot wounds. He wondered what had occurred until he saw the remains of the body of a particularly big man. There was enough of the chest skin left intact for Uwa to see the ceremonial markings of a Baadu of Warrdarrgana. He shook his head. He himself had eaten human meat food, but neither he nor anyone else in his tribe was a blood drinker. Perhaps, he thought, the final fight that had left five Baadu dead had been precipitated by a Baadu attempt to secure one of their favourite meals.

A shout turned his head, and he hurried, galvanized by the urgency of the call, to a spot where his companions had found a whitefella who was very, very sick. A big whitefella, he lay on his stomach, burning with fever. A young man pointed to the cauterized wound on the whitefella’s back.

“A hole to let the life out of him,” the young man said.

“And yet he fights to live,” Uwa replied.

A waterskin lay near the whitefella. Uwa squatted and squeezed drops of the muddy liquid onto the whitefella’s lips. A swollen tongue moved, licking at the water.

“The djugurba will walk here tonight,” said one of the young men uneasily. He spoke of the things of the desert, partly human, partly animal or reptile or bird.

The whitefella was greedily licking at the drops of water; Uwa doled them out slowly, knowing that it would not be good to give too much water at once. When Uwa stopped, the whitefella groaned and opened his eyes.

“You drink little now, little later,” Uwa instructed.

“Please,” the whitefella croaked.

“Will he die, Grandfather?” asked one of the young men.

“Only those of the Dreaming can say,” Uwa said. “We will move him from this place.”

“I welcome a leave-taking from this stink,” said Uwa’s number one grandson.

“Perhaps moving him will finish the job that these tried to do,” Uwa said, indicating the dead blackfellas.

“Another whitefella was here,” said the grandson. He pointed to the tracks that Terry Forrest had made in leaving.

“Handle this one gently,” Uwa ordered.

“Would it not be kinder to leave him here to die?”

“We will give him warmth in the night with fire. We will give him water and food,” Uwa said. “If he dies, then it is the will of the Dreaming and not of our doing.”

“That is true,” said the grandson, lifting Tolo’s feet while his companion put his hands under Tolo’s arms and heaved.

“This one is heavy.”

Tolo made one grunting protest and then sank back into his merciful state of coma. At the campsite the women applied a poultice to his wound, as well as leaves carried all the way from their homeland, and they took turns squeezing drops of water onto his lips.

There was some grumbling when Uwa announced that they would camp here as long as the billabong held water or until the whitefella died. Uwa told them sternly to use their time profitably, to look for the edible tubers that made life possible in the never-never, to hunt mamuru, the long-haired rat of the spinifex plains. The whitefella would live or die in his own time. That it would be death seemed almost certain when, as a result of the water that the women rationed out to the injured man, he urinated and it was red with blood. But in the cool of evening he opened his eyes and took food.

It took three days for the sun to evaporate the last of the surface water in the wash. Uwa knew that he must move on. The whitefella was experiencing periods of semiconsciousness during which he prattled in his own language. Uwa’s grandson, who spoke a little English, said that the whitefella’s words did not make sense.

“He will die,” the grandson said, “for he still passes blood. It would be kinder to end it for him than merely to leave him here to die alone.”

“We will do neither,” Uwa said. He showed them how to use the limited materials available, strong mulga sticks and a blanket, to rig a litter. The young men complained but did as they were told, and soon the mob was under way, with the whitefella riding in the litter carried by four of the men.

Water was scarce now, and the food inadequate even for those who were accustomed to meagre bush tucker. Uwa saw to it that the whitefella got more than his share of the water, and he watched interestedly as the women got the man to swallow mashed-up starches from the tubers.

The grandson grumbled, “It seems that the whitefella will live all the way to our homeland.” For with each day the man seemed to grow stronger. He stayed awake for longer periods, and his words were delivered in a more orderly manner. His urine no longer contained blood; but when the grandson tried to make him stand, his legs gave way weakly, and he crumpled to the ground. Then, just when it seemed that the whitefella was gaining the use of his legs, the wound began to fester. The fevers came again, and in spite of the women’s efforts to scrape away the stinking dead flesh around the wound, their patient sank once more into a coma.

And still Uwa would not give up. The spirits of the Dreaming came to him in the night, in a sleeping dream, and there he saw the whitefella — he had come to think of him as his whitefella — strong and powerful, joining Uwa in a hunt, bringing down a great juicy kangaroo at an incredible distance with a native spear.

“The spirits of the Dreamtime have spoken to me,” Uwa announced at dawn. “The whitefella will live.” He insisted this day on taking his turn at one comer of the litter, and the drained face of the whitefella, his limpness, caused him almost to despair. But the spirits of the Dreamtime had spoken, and he would not allow the whitefella to die. He would keep him alive by the force of his own will.

Terry Forrest had been in some tight places before. He had done his tour in the old queen’s war in South Africa, and he had seen men die — Aussies, Brits, and Boers. He’d come close to death himself a couple of times, but never as close as he came before he stumbled down to one of Jonas Mayhew’s water holes in the dry bed of the Gascoyne.

Later, even after he had glutted himself with water and huge slabs of roast mutton, Mayhew’s scales showed that he’d lost more than forty pounds in his trek from the camp where Ganba and the others had died. He had pushed himself to the limit each day, resting only in the torrid noontime, walking onward long after dark. He had known that his chances for survival were in direct proportion to the amount of time that he took to reach the Gascoyne with its life-giving soaks. There was a delicate balance between exertion, the time consumed, and the skin of water that he carried.

He made the walk in ten days, the last two without water. He was weak and disgusted. At first he rebuffed all of old man Mayhew’s questions, but he knew that sooner or later he would have to answer to someone about Tolo Mason and his pretty little wife. He hadn’t thought much about that during his dash for life across the western Gibson. Now, under the questioning stare of Jonas Mayhew, he put together the story that if necessary, he would tell to the authorities later.

“That Ganba and his bloody boongs,” he told Mayhew, “wanted all of the equipment. Ganba was leading Mason on a chase, taking him into the driest parts of the waly, just waiting for him and the girl to die so that he could get his hands on the food, the guns, the camping equipment, and the money that Mason had with him.”

“The boy took money into the outback?” Mayhew asked.

Terry nodded. He knew very well, to the pound, how much money Tolo had carried in his pack, for that money now was safely tucked away in Terry’s own wallet. He had removed it from Tolo’s possessions, rationalizing that money would be needed to send a rescue expedition to recover the remains for the boy’s family off in Sydney.

He told Mayhew the rest of it, how he and Mason had been caught in the flash flood and all the events that followed up to the time that the boong woman put the spear into Mason’s back. In his telling he altered the facts only slightly. He left out any mention of a fight between Mason and himself, and he said that the spear thrust killed Mason almost immediately.

The girl? “Well, I can only guess,” he said. “She had one friend among the boongs, old Ganba’s wife. Her name was Bildana. She must have known that sooner or later the little whitefellow lady would be tender meat food for Ganba and the others. And since Bildana had sided with the white sheila, old Ganba was down on her. When the boongs killed the camels — you know how they are, a meal in the hand is worth feasts in the future — and then ate one of their own, it must have made Mrs. Mason understand the immediate danger she was in. She and Bildana took off and got away from old Ganba in the rain. We lost her trail, too, because of the rain. We figured she would head for the station here.”

“Logical thing to do, but would she have known enough to be logical?” Mayhew asked. “And wouldn’t the Abos have guessed that she’d head west?”

“ ’Strewth,” Terry said. Bildana would have known that. And Java Mason wasn’t stupid. “The sheila went east!” It hadn’t occurred to him before, but the thought had a ring of truth. “Bildana would have known that Ganba would be able to overtake them if they went in the direction he expected them to go. Bildana knew how to live in the waly. Yes, by God, they went east. They’re going to try to make it all the way across.”

“Well, you’ll never find her bones, then,” Mayhew said.

“Don’t bet on her dying,” Terry said. “She’s a tough little bird. And that Abo woman would know what to eat, where to find the soaks and the bores.”

In that moment, although he was still weak, Terry made his decision. He had not felt guilty about leaving Tolo to die, for a man with a spear through his kidney had only a short time to live. He knew that he, too, would have died if he had tried to drag Tolo along with him or if he had tried to search for Java Mason. No, guilt as such did not enter Terry’s mind, only speculation that was part of a chain of reasoning. What if he hadn’t had eyes for the little bird and thus raised Tolo’s hackles? What if he hadn’t felt compelled to find out who had the harder head, he or Tolo Mason? What if he’d paid more attention to the damned boongs when he and Tolo caught up with them?