Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

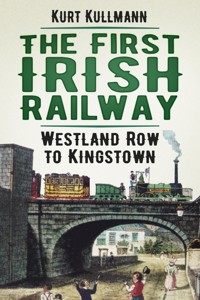

The first Irish railway ran from Westland Row, in the centre of Dublin, to Kingstown, then a seaside resort on the coast south of the city. This historic line is now the DART line, Kingstown has become Dún Laoghaire and the world has changed around it. In this work, historian and author Kurt Kullmann recreates this era and takes us on a scenic journey through Ireland's past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 167

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The runaway train went over the hill,And the last we heard, she was goin’ still

First published 2018

The History Press Ireland

50 City Quay

Dublin 2

Ireland

www.thehistorypress.ie

The History Press Ireland is a member of Publishing Ireland, the Irish book publishers’ association.

© Kurt Kullmann, 2018

The right of Kurt Kullmann to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8856 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements and Reminiscences

Abbreviations

Preliminary Remarks

In the Beginning was the Steam

Plans for the First Irish Railway

Also in the Beginning was: The Royal Mail

Yet Another Beginning: The Asylum Harbour

Some Worries

Companies and Lines

The Route

Engineers, Builders and Architects

Termini

Stops and Tariffs

Rolling Stock

Explanation Concerning Steam Locomotive Classification

Manpower

Changes on the Line

The Elevated Stretch

The Flat Stretch on Land

The ‘Water’ Stretch

The End Bit

Memories of Railway Passengers

Further Reading

Picture Credits

About the Author

Notes

In memoriam

Clemens Alexander Joseph Winterscheid (1843–1927), Köln-Mindener Eisenbahn

Wilhelm Winterscheid (1871–1948), Kölner Straßenbahnen

Michael Cremen (1838–1922), Great Southern & Western Railway

Patrick Donovan (1841–1881), Cork and Bandon Railway

Acknowledgements and Reminiscences

The greatest thanks go, as always, to my wife Catherine, née Donovan. She is great at finding sources and discussing sections of my books. Her memories are invaluable to me, as she grew up on a street that runs parallel to the first Irish railway line.

For my own interest in anything that travels on rails, I have to thank my late parents, Carl Kullmann and Dr Maria Theresia Kullmann, née Winterscheid. I was a little more than 6 years old when my older brother and I found an electric railway under the Christmas tree. This electric railway evolved into a rather complex system over the next ten years.

Until my early teen years, I grew up in a West German market garden village, which meant that any shopping other than victuals had to be done in nearby towns, the bigger ones being Bonn and Cologne. Both of these were reached by a private railway (standard gauge).

Once I had started secondary school, this railway was also used to travel to school, until we moved to a town to the east of Cologne. This town had train and tram connections with Cologne. We lived beside the railway line, next to a level crossing. My path to school followed, at least in parts, this railway line. Shopping, going to cinemas or theatres or visiting relations usually meant using the tram, which went much more frequently than the train.

I started my studies at the University of Würzburg, where I encountered a narrow-gauge tram system. I still remember the screeching of the old tram cars when they went around sharp corners. Not that I used the tram much. Würzburg is a compact town and my budget was low, so I usually walked.

Würzburg was around 300km away from home. I went there by train at the beginning of each term and travelled home again by train at the end of each term. During my first years, these trains were still pulled by steam engines. I usually enjoyed the journey home for Christmas, which involved crossing the hills of the Spessart and going along the Rhine when everything was white with snow. However, there was one time when traffic was heavy and I had to take an additional train made up of old carriages. Unluckily, those old carriages had not been checked extensively and we soon discovered that the heating system had broken down. We spent four hours in an icy-cold compartment, huddled in our thick winter coats, watching the condensation freeze on the inside of the window.

My last student ‘action’ in Würzburg included my longest train journey ever. I was studying mineralogy and the university had organised an excursion to inspect some working mines – in Turkey. First we had to go from Würzburg to Munich, which took a couple of hours. In Munich, we had to change trains. The train journey from Munich to Istanbul took a day and a half. Most of us students did not have the money for a bed in a sleeper. We arranged ourselves as best as we could in our compartment. I, as one of the two youngest and lightest, was elected to sleep in the luggage rack. I remember that I slept surprisingly well that night.

In Bonn, where I continued my studies, the tram situation was the same as in Würzburg, except that I walked beside tram tracks of standard gauge instead of narrow gauge. But I had experiences with trains nonetheless, although not so much as a passenger. One of the main north–south railway lines of Germany was built right through the middle of the city of Bonn. There were lots of level crossings and lots of trains. This led to the saying, ‘I studied in Bonn for nine terms, which includes the three terms that I had to wait at a level crossing’.

As a mature student in Cologne, I drove myself to classes and meetings with my tutor. By that time, the tram systems of Cologne and Bonn had been combined. They also had been put underground in places.

At that stage I was married and had a family. I had also become interested in family history. I discovered that my great-grandfather Clemens Alexander Joseph Winterscheid started his working career as brakeman on the Köln-Mindener Eisenbahn and worked his way up to technician and finally railway engineer. At that stage, Germany, like Ireland, had a lot of private railway companies that shared their names with their railway termini. My great-grandfather’s eldest son, my grandfather Wilhelm Winterscheid, was also a railway engineer. He did not work with trains, though, but with the trams in Cologne.

When we finally came (back) to Ireland, we moved into Catherine’s parents’ house with her widowed father. As I mentioned before, this house is on a street that runs parallel to the railway line that was formerly the Dublin & Kingstown Railway. Our part of this street is nearly exactly 100 years younger than the railway line.

I was kept busy with family history – there was a whole new branch to be researched – and so I discovered that Catherine had two great-grandfathers who had been involved in railways: Patrick Donovan was, at least at the end of his short life, an engine driver, most likely on the Cork and Bandon Railway, and Michael Cremen started as stoker and worked his way up to engine driver on the Great Southern & Western Railway. He actually drove the first train from Tralee to Cahersiveen. Later he worked on the Cork–Tralee route.

There have been many changes in railways, even in the nearly seventy years during which I have been interested in anything that travels on rails. This book is one of the results of that interest. I dedicate it to all the people mentioned, but especially to my grandfather, my great-grandfather and my two great-grandfathers-in-law.

A heartfelt thank you is due to John Eugene Mullee of Houston, Texas, who grew up around the corner from the house my wife Catherine grew up in, so that he could look into our back garden from the back bedrooms in his house. He, like me, for some years used the train to go to school as well and his memories were very helpful, especially as he used the stretch from Sandymount to Westland Row.

Special thanks go to Ciarán Cooney of the IRRS and Charles Friel of the RPSI, who provided photographs and information. Thank you also to those who allowed me to reproduce photographs: Albert Bridge, Keith Edkins, Harold Falye, Michael Costello.

Abbreviations

AIB

Allied Irish Bank

CC

Cricket Club

CDJR

City of Dublin Junction Railway (known as the Loop Line)

CIÉ

Córas Iompair Éireann

DART

Dublin Area Rapid Transit

D&KR

Dublin and Kingstown Railway

DSE

Dublin and South Eastern Railway (also known locally as

Dublin Slow and Easy)

D&SER

Dublin and South Eastern Railway

DUTC

Dublin United Tram Company (1891–1941)

DUTC

Dublin United Transport Company (1941–1945)

DW&WR

Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford Railway

ESB

Electricity Supply Board

FC

Football Club

GSR

Great Southern Railway

GS&WR

Great Southern and Western Railway

IÉ

Iarnród Éireann

IRRS

Irish Railway Record Society

IT

Information Technology

L&MR

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

NIR

Northern Ireland Railway

OS

Ordnance Survey

RDS

Royal Dublin Society

RPSI

Railway Preservation Society of Ireland

S&DR

Stockton and Darlington Railway

SDUK

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

TCD

Trinity College Dublin

UIC

Union Internationale des Chemins de Fer (International

Union of Railways)

WWW&DR

Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow and Dublin Railway

Preliminary Remarks

Transport on rails or fixed routes of one type or other is a very old form of transport. Possibly the best-known example from antiquity is the Diolkos on the Isthmus of Corinth, on which ships were pulled 6.4km (4 miles) over the isthmus between the Saronic Gulf and the Gulf of Corinth, saving them the long and dangerous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese. It was used from around 600 BCE (Before Common Era) to around 50 CE. (Common Era).

In the late Middle Ages, miners used carts to transport the ore out of their tunnels in the mountains. Those carts had wheels that sometimes ran in grooves or that had a pin that ran in a central groove to keep the laden carts running the way they were expected to run, especially in the dark environment of an underground mine.

Miner with mine car running in grooves.

Mining car; F denotes the pin that runs in a central groove.

The woodcut on the preceding page shows the grooves in which the wheels of the little car roll. The above woodcut, from the same book, shows another system with a pin underneath the car that runs in a central groove.

What we regard as a railway now is quite different. Again, rails for transporting goods and passengers were known for quite some time before the first railways, as we know them, were built. Their precursors were pushed by people or pulled by horses, whereas our idea of a railway is based on trains being pulled by some kind of engine. The railway era, in this sense, started with steam engines.

In the Beginning was the Steam

Steam engine, machine using steam power to perform mechanical work through the agency of heat.1

The first known device that used steam to set something in motion was the Aeolipile, a steam turbine invented in the first century CE by Heron of Alexandria. The first commercially used steam engine with a piston was the atmospheric engine of Thomas Newcomen (1664–1729). Newcomen constructed this in 1712 to pump water out of a mine. In general, the person most thought of when talking about early steam engines is the Scottish inventor James Watt (1736–1819), who improved Newcomen’s engine in such a way that it could be used for all sorts of different work in different situations.

Those steam engines were stationary. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, inventors experimented with steam engines on wheels. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines a railway as follows:

A railroad (or railway) is a mode of land transportation in which freight-goods and passenger-carrying vehicles, or cars, with flanged wheels move over two parallel steel rails.2

This definition does not say anything about the power that is used for this land transportation. In general, it is locomotives, moveable engines, powered by steam in the beginning, that come to mind when thinking or talking about a railway:

A steam engine is by nature a small explosion of power. It claims most of your senses – not just your eyes and ears – especially if you are standing on the edge of the railway platform as it thunders past without stopping. Even standing close to a steam engine when it is only starting to move is an exhilarating experience.3

Plans for the First Irish Railway

The first public railway line with steam locomotives was the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) which opened on 27 September 1825. During its first years, it only transported goods (mainly coal) in trains pulled by steam engines; passenger carriages were still pulled by horses. The first public railway using steam engines to transport passengers was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), which opened on 15 September 1830. This was the beginning of the development of railways, which ultimately became so frenzied that it was called ‘railway mania’. Railways were regarded as a good investment and every area wanted at least one railway line. Railways were run by publicly subscribed private companies that usually had the termini in their names (S&DR, L&MR, D&KR) until some of those companies merged and the companies’ names described the area they worked in (D&SER, GS&WR, GSR). Ireland got its first railway in 1834.

Also in the Beginning was: The Royal Mail

Even after the union of Ireland with Great Britain on 1 January 1801, the mail service between London and Dublin was very important, despite the fact that Dublin had lost its function as a capital. Originally mail boats travelled to Poolbeg, near Ringsend. When ships became bigger, this stopping place a few miles east of Dublin, which had never been quite satisfactory, became too difficult to reach. Sailing up to Dublin on the Liffey was no longer an option as the water was not deep enough, but even anchoring places like Poolbeg were not easy to reach due to the many, often shifting, sandbanks across the mouth of the Liffey, where it flows into Dublin Bay:

Many ships were grounded as there was only a narrow path through the sandbanks to the river mouth. It needed skilled captains to negotiate the dangers. Because of this, there was a huge waiting time. Ships were anchored out there for days before being allowed in.4

But more and more freight had to be shifted into and out of the growing city, with bulky goods like coal coming from across the Irish Sea.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Ringsend/Poolbeg/Pigeonhouse was definitely no longer an adequate port for Dublin. Despite the fact that Dublin was not a capital city any more, good mail connections were still very important. Waiting times on the Irish side needed to be eliminated as quickly as possible.

A new harbour was planned. Howth, which already had a fishing harbour, was chosen. Unfortunately, the position for Howth Harbour was decided upon without listening to the local experts and the newly built harbour began to silt up almost immediately. The mail boat service had been given to Howth in 1818, but not much more than fifteen years later, the harbour had been filled with so much silt and sand that it was much less deep than it had been originally and the mail boats had become longer and wider and, significantly, had a bigger loaded draught. Thus, it was no longer practicable to send the mail boats to Howth. On the other side of the Irish Sea, the Menai Bridge had been built in 1826 to eliminate the necessity of crossing the Menai Strait by ship, thus shortening the time the Royal Mail needed to reach Dublin from Holyhead. With those bigger mail boats and the pressure to shorten the time of the journey between London and Dublin, Howth Harbour was no longer adequate.

What is now known as Dún Laoghaire Harbour was originally planned as an asylum harbour for ships in distress. The first stone was officially laid in May 1817. Soon, this harbour was given other functions, even before it was finished in 1842. The first steamboats coming from Liverpool were too big for Howth and travelled to Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) from 1826. The official Royal Mail went from Holyhead and used Howth until April 1834, when the harbour of Kingstown was finally chosen for the Royal Mail. From there, it was brought to Dublin by government coaches during the period from April 1834 to April 1835, whereupon the railway took over. In 1848, the railway link between London and Holyhead was completed, which improved the speed of the service enormously.

Yet Another Beginning: The Asylum Harbour

Frequent and violent eastern gales led to many shipwrecks in Dublin Bay up until the eighteenth century, as there was no safe place for ships seeking protection from inclement weather. The double catastrophe of the Rochdale and the Prince of Wales in 1807, with the loss of hundreds of lives, was the last straw. The cry for an asylum harbour could not be ignored any more. An asylum harbour, however, could only be built at a location where the sea was sufficiently deep until quite near the land, which ruled out anywhere around the mouth of the Liffey. The small fishing village of Dunleary was chosen as the location for this new harbour. Dunleary had a tiny pier already, but this was not at all sufficient for what was intended. And so it was that between 1817 and 1842, the biggest man-made harbour of Western Europe was built 15km (9.3 miles) south-east of Dublin’s city centre.

What became the port of Kingstown (later Dún Laoghaire) was originally planned as an asylum harbour, a place where ships in distress could find shelter from the frequent, strong easterly gales on the Irish Sea. Soon it became much more.

King George IV left Ireland from this harbour at the end of his visit in 1821, which gave a big boost to the community that had started to grow on the hill above the harbour and which had been quite small until then. To commemorate the king’s visit, they chose to rename the village, which soon grew into a small town, ‘Kingstown’. The increasing number of ships at the new harbour led to different surveys and plans for getting the goods to Dublin. This became a more pressing concern when Kingstown took over from Howth as the Irish port for all mail boats. The original asylum harbour for ships in distress had definitely developed into a ‘normal’ harbour for goods and passengers and, of course, for the Royal Mail.

The first idea for getting the goods to Dublin City had been to transport them by boat on a canal that would connect the KingstownHarbour with the Grand Canal Basin between Dublin City and Ringsend. Not much later, others proposed connecting the city with the port using a railway line. It took some time before the proponents of the railway won over the group favouring a canal. The increasing number of passengers that arrived in this harbour might have influenced the decision. And so Ireland got her first railway, a couple of years later than England and France, but a year earlier than Germany.