Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

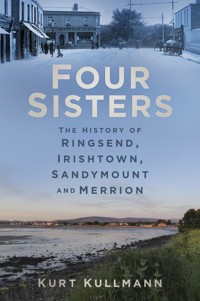

This book traces the development of the four coastal villages – often referred to as 'the Four Sisters' – that make up the eastern part Dublin 4 from their foundation to the present day. Richly illustrated with modern and historic images, this work looks at the social, political, religious and economic history of Ringsend, Irishtown, Sandymount and Merrion, recalling the significant events, vanished industries and local characters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For three brothers

John Carl, Michael Denis, Christopher Hans

When you grew up you stayed sons

but you also became friends.

Thank you.

First published 2017

The History Press Ireland

50 City Quay

Dublin 2

Ireland

www.thehistorypress.ie

The History Press Ireland is a member of Publishing Ireland, the Irish book publishers’ association.

© Kurt Kullmann, 2017

The right of Kurt Kullmann, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8536 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ International

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Early history of the area

2. Ringsend

3. Irishtown

4. Sandymount

5. Merrion

6. A walk along the coast

Sources and further reading

Notes

INTRODUCTION

COASTLINE

Dublin Bay keeps changing. The changes to its western end during the last millennium around the mouths of the rivers Liffey, Tolka and Dodder were quite far-reaching and many of those changes were caused by humans. It is not possible to trace all changes in detail, as old maps are less exact than modern ones. Sometimes clues to a former borderline between land and sea are found when laying foundations for new buildings. The map of a probable shape of the Liffey mouth at the time of the Battle of Clontarf shows a remarkable difference to the situation today.

Western end of Dublin Bay, the Battle of Clontarf.

The four villages (suburbs) of Dublin 4: Ringsend, Irishtown, Sandymount and Merrion are often referred to as the four sisters, having many things in common, but also some very individual characteristics. Most parts of the four villages are built on low-lying land, much of which has been reclaimed from the sea. Sandymount DART Station is only 2.5m above sea level (Malin Head Ordnance Datum). Much of the land in these coastal villages lies even lower, some of it below sea level. The whole area is partly sandy, partly swampy or marshy and was often inundated for many centuries. Former landlords – the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Viscounts Fitzwilliam of Merrion and Barons Fitzwilliam of Thorncastle – had clay dug from the southern part of this area to make bricks when they developed Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and the area between them in the eighteenth century. This activity lowered the ground level even more and Richard, Seventh Viscount Fitzwilliam, had to build a wall at the edge of the sea to protect his land. This wall still exists and has protected Merrion and Sandymount for more than 200 years from being submerged by the sea, though lately insurance companies have insisted that it is not quite high enough.

As far as distance from Dublin city centre is concerned, Lewis1 mentions that Ringsend is 1½ miles (2.5km) from the General Post Office, Sandymount 2 miles (3.5km) and Merrion 3 miles (4.8km). Lewis includes Irishtown in his Ringsend entry. Modern maps give a distance of 1⅞ miles (3km) from the GPO to Irishtown.

TOWNLANDS AND VILLAGES

In Ireland townlands are the smallest administrative divisions of land. They are also the oldest divisions as they arose in Gaelic culture and go back to times before the Norman invasion. Pembroke Township had fifteen townlands. Present-day Dublin 4 added two whole townlands and parts of two more. This enlargement was caused by the expansion of Donnybrook village southwards into the former barony of Rathdown. Baronies were subdivisions of counties from the time of the Tudors until the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898.

Pembroke Township did not exceed the borders of the former barony of Dublin. The fifteen (or nineteen) townlands grew into six villages – or seven if Baggotrath is counted as a village in its own right. The four coastal villages spread out from the original townlands of the same name. Over the years some of them increased their area considerably. Two sketches show the differences in the example of Ringsend. In those maps the borders of the townlands or villages are shown with the border of Pembroke Township in a stronger line. Major roads and the railway are also shown.

The map shows that the townland ‘Ringsend’ is situated east of the Dodder with the Liffey as border to the north, the sea to the east and what now is Oliver Plunkett Avenue as border to Irishtown in the south.

The map of the villages of Pembroke Township shows that the village ‘Ringsend’ includes nearly the whole of the townland South Lotts (onto the railway) and the northern part of townland Beggarsbush (up to and including Shelbourne Park Stadium and Shelbourne Park Apartments).

In the case of Irishtown the difference is even greater as the village does not only include the part of Beggarsbush townland south of Ringsend but also most of the Poolbeg Peninsula that was reclaimed from the sea south of the South Wall.

It has to be said here that those village borders are not universally accepted. The borders as shown on the map sketched above are suggestions rather than exact borders. It seems more convenient to take the railway as a border to the west instead of sticking to old townland borders, which were more often than not determined by property rights. South of Sandymount Avenue this adjustment has been made by the OS map of 1907, compared with the map of 1837. Holyrood Castle, however, and its surroundings east of the railway are in Smotscourt townland, which in its bulk has turned into the southern part of Ballsbridge. Now the part east of the railway is regarded by most people as part of Sandymount village. The Roman Catholic Parish Church of Sandymount, the Church of Our Lady Star of the Sea, is on Irishtown townland and ‘Sandymount’ Martello Tower at the other end of Sandymount is in Merrion townland, but most people would think of them as part of Sandymount.

GEOGRAPHY OR HISTORY?

The most common way to list the four coastal villages of Dublin 4 is in the geographical sequence from north to south: Ringsend, Irishtown, Sandymount and Merrion. This is, however, not the sequence in which the villages developed. Seen historically, Merrion is the eldest, most likely starting in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, followed by Irishtown which became established in the fifteenth century. After Irishtown follows Ringsend which according to some authors might be older, but most regard it as developing into a village in the late sixteenth century. The youngest is Sandymount, which only began to develop in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Even though sisters are usually listed according to age, here the geographical line is followed, as if taking a walk from the Poolbeg lighthouse along the coast to the southern border of Dublin city. Despite the fact that in modern times Irishtown quite often is described as if it were incorporated into Ringsend, and Merrion as if it were part of Sandymount, here each village will be mentioned as a separate and complete unity, each with its own character and history.

1

EARLY HISTORY OF THE AREA

PRE-NORMAN TIME

Latest research indicates that the first humans reached Ireland in the Palaeolithic Era, around 12,000 years ago. The area south of Dublin, however, seems to have been populated much later. The first signs of people living there date from the end of the Mesolithic times, c. 4,000 BC, with finds on the north shore of the mouth of the Liffey and on Dalkey Island.

After that there was a long gap. Not that there were no people around – there might have been – but nobody knows anything about them. That people were living at that part of the coast is in no doubt, but it has been documented only much later.

The first event in this area for which a definite and documented date exists was the arrival of St Palladius on the Dublin and Wicklow coast in AD 431, sent by the Pope to the Christian inhabitants of Ireland as their first bishop. That of course means that at this early time it was already known in Rome that there were Christians in Ireland. As those Irish Christians possibly were slaves who had been captured in Wales, England or France, St Palladius’s arrival was not welcomed by the slave owners who did not want their slaves, who were their property, meddled with by some weird stranger. St Palladius is said to have built a few churches, but then he himself evaded the opposition and went to Scotland to Christianise the Picts. He had asked some of his companions to stay, however, even leaving them some books, which in those days were very valuable possessions.

Before the arrival of the Vikings (also called Norse, Ostmen and sometimes Danes, though the latter did not include all of them) the coast south of the Liffey was part of Cualand (also Cualann or Cuala), settled by the Uí Briúin Cualand.

The Uí Briúin appear to have occupied the coastal district south of the River Liffey at a very early date, perhaps before AD 500, and to have gradually extended their territory further to the south.1

The Uí Briúin Cualand were part of the Uí Dúnchada and in the twelfth century the ruling family of the Uí Dúnchada were the Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc who accepted the Normans as overlords later and changed their name into FitzDermot after one of their chiefs, Diarmaid Mac Gilla Mo-Cholmóc.

The Dublin area suffered Viking attacks from the eighth century on, but most of those early attacks were short raids, looking for treasure and for people that could be sold as slaves. In the ninth century the Vikings established a permanent post on a rise between the Liffey and Poddle rivers. This grew into a town of probably a few hundred people, and the surrounding area became a kingdom, which the Vikings called Dyfflinarskiri. From its beginning until the Normans arrived in Leinster and defeated the Norse, their distant cousins, the south-east coast of Dublin Bay belonged to this kingdom. Through a grant of Richard de Clare, in Ireland better known as Strongbow, to his companion Walter de Ridelesford, it is known that the Mac Torcaill family, the last dynasty of the Norse kingdom of Dublin, held land in this coastal area. Even after the beheading of the last Norse king Ascall Mac Torcaill (also referred to as Askulv Mac Thorkil or in Norse as Höskellr Thorkelson) some members of this family held land in what now is south County Dublin and north County Wicklow.

AGE OF THE COASTAL VILLAGES

The majority of historians regard Merrion as the oldest of the four villages, as it grew around Merrion Castle, which was first mentioned in 1334 but probably was built during the thirteenth century. This castle was situated where St Mary’s Asylum for the Female Blind used to be, which now is St Mary’s Centre of the Religious Sisters of Charity. T.W. Freeman held another opinion about the age of these villages. According to John W. de Courcy2 Freeman thought that Ringsend was older than Merrion and started at the same time as Dublin. These were two different settlements that occupied two patches of slightly raised and therefore dry ground.

As far as Irishtown is concerned, John W. de Courcy says:

Human habitation at Ringsend (An Rinn) dates back almost certainly before 900. So far as this book is concerned, it has always been there. It seems likely that the area of Irishtown was inhabited at the same time, that the two were one community.

Most historic publications describe the coastal villages as younger. Thorncastle (roughly at modern Williamstown) and Merrion were fortified mansions to guard the Pale. They were probably built in the thirteenth century. Irishtown as a village is mentioned in the fifteenth and Ringsend in the seventeenth century. A description of ‘Riding the Franchises’ in 1488 mentions ‘Ring’s-end’ but this description does not mention inhabitants in this area.3 It might have been a landing place, though, from very early on.

Galleys of the Lochlanns ran here to beach, in quest of prey, their bloodbeaked prows riding low on a molten pewter surf. Danevikings, torcs of tomahawks aglitter on their breasts when Malachi wore the collar of gold.4

The reference to Malachi indicates the time. Two Irish high kings had that name: Malachi I (Máel Sechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid) died 27 November 862, and Malachi II (Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill) lived 948–1022. The reference to the coming of the Vikings points to Malachi I. It should be mentioned, however, that the quoted author had a good reputation as a singer and an even better one as a wizard with words, but he cannot be thought a reliable source for historical facts as the people of Lochlann (meaning Scandinavia, especially Norway) did not have ‘galleys’ – or ‘tomahawks’.

A second – similarly fanciful – quote talks about Ringsend as a town at a time 300 years later than the first. It was allegedly made by one of Ringsend’s ‘nobility’, a lady whose father was according to her ‘a boatbuilder beyond at Ringsend’ and when questioned if he really was a boatbuilder she replied, ‘Yes. In Ringsend, a town that thrun back Strongbow and send him on to Dublin.’ 5

NORMAN CONQUEST

When the Normans arrived in Ireland from Wales, their leader was the Cambro-Norman knight-adventurer Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, Earl of Strigoil (modern Chepstow), like his father nicknamed ‘Arc-Fort’ (Strongbow). His father had been Earl of Pembroke, but this title was not conferred on the son by King Henry II. This was probably in retaliation for the fact that in the struggle between King Stephen and the Empress Maud both father and son had supported Stephen against Maud, the mother of the later established king, Henry II. Strongbow had some disputes with his overlord Henry II FitzEmpress, King of England, Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine, Count of Anjou, Maine and Nantes (and probably many more minor titles, especially in France), concerning the Irish lands he had conquered. As Strongbow had married Aoife, the daughter of Diarmaid MacMurchada, King of Leinster, he had, according to Norman law, inherited the right to rule Leinster, including the city of Dublin, after Diarmaid’s death. King Henry II was afraid that his vassal might conquer even more land and eventually make himself King of Ireland; therefore he forced him to hand Dublin over to his king, but let him keep Leinster as lordship under the king’s suzerainty.

Strongbow himself then granted some of this land to other adventurer-knights who had accompanied him to Ireland. The best part of the coastal area as well as stretches of Kildare went to Walter de Ridelesford6 in grateful acknowledgment that this knight had killed John de Wode, a fierce warrior and one of the important jarls that had come to support the Norse king of Dublin against the Normans. At least that is what stories about de Ridelesford say.

Walter de Ridelesford, who was subsequently referred to as Lord of Bray, was married to Amabilis, daughter of Henry FitzRoi and thus a granddaughter of King Henry I. She was also half-sister of Meiler FitzHenry, the first Justiciar of Ireland. Walter de Ridelesford’s son and heir, also named Walter de Ridelesford, and his wife donated part of their land unconditionally to the Priory of All Hallows7 and another 39 acres to the same priory for the rent of one pound of pepper annually.8

2

RINGSEND

THE NAME

The name ‘Ringsend’ sounds like a combination of an Irish and an English word. The Irish word ‘rinn’ means ‘point, headland’ and is used to describe the end of the narrow peninsula between the Dodder and the sea. The name was mocked by some English writers who did not know the background and pointed out the stupidity of the Irish not knowing that rings had no end.

Those writers were not prepared to understand that the first part of the name was not the English word ‘ring’. Actually the second part of the name of Ringsend also has nothing to do with an English word. The ‘-end’ part was a corruption of another Irish word. According to S. Lewis, the name originally was Rin-aun (modern Rinn-ann):

This place, according to O’Halloran, was originally called Rin-Aun, signifying in the Irish language, ‘the point of the tide’, from its situation on the confluence of the Dodder with the Liffey; its present name is a singular corruption of the former ...1

Some years ago there still was an old signpost on the way to Ringsend from the city and ahead of the bridge across the Dodder, pointing towards the sea and bearing the inscription ‘Rinn Muirbhthean’ (the Point of Merrion).

RINGSEND HISTORY: PIGEON HOUSE AND SOUTH WALL

Ringsend was a landing place for people and some goods since at least the fourteenth century.2 This does not necessarily mean that people lived permanently there; it might just have been a place where goods and people disembarked for Dublin.

Later bigger ships with goods for Dublin anchored in Dalkey Sound, but this seems to have changed again around the end of the sixteenth century. From that time Ringsend was regarded as the official harbour for Dublin3 and many people will know that Oliver Cromwell landed there in 1649. Less well known is what D’Alton says about this event, quoting the memoirs of Edmund Ludlow (1698):

On his arrival in the bay of Dublin the men-of-war that accompanied him, and other ships in the harbour, rung such a peal with their cannon, as if some great news had been coming. He and his company went up in boats to the Ringsend, where they went ashore, and were met by most of the officers, civil and military, about the town; the end of his coming over was not at first discovered, and conjectured to be only to command in the army as major-general under Fleetwood.4

The expression that they ‘went in boats to the Ringsend’ indicates that ‘the Ringsend’ was a landing place, not a living place. At those times ships at the Ringsend did not moor at a wharf, but anchored in ‘Poolbeg’ (from the Irish ‘poll beag’, meaning a small deep place).

Around that time a wall alongside the Liffey to the mouth of the Dodder was built. This is now known as Sir John Rogerson’s Quay. The ‘harbour’ or better the anchoring place Poolbeg can be identified in the engraving by the agglomeration of ships in the bay near the then existing village of Ringsend. Even when the South Wall had been built further out and was nearly finished, it could have happened that part of it gave way and the land that had been reclaimed behind it became submerged again. This occurred for instance in January 1792 when the Duke of Leinster managed to sail with his yacht across the flooded South Lotts and moor behind his house (Leinster House) in what was to become Merrion Square. The 1745 engraving of the view from Beggars’ Bush shows also that Ringsend and Irishtown were separate entities with the majority of buildings in Ringsend and with St Matthew’s Church in Irishtown just appearing at the right edge of the engraving.

To get from the port in Ringsend to Dublin was not easy, as the Dodder had to be crossed. Even today this river still is not completely tamed, but in the seventeenth century not much effort had been made even to try to do so. Bridges across it had been built since at least 1640 and probably much earlier, most of them much further upriver as in Ballsbridge, Donnybrook and even Clonskeagh, but many were destroyed by floods. In Ringsend the Dodder could be crossed at low tide in a ‘Ringsend Car’, which was a horse drawn vehicle with a seat suspended between two wheels which had wide rims to prevent them from sinking into the wet sand.

The view from Beggars’ Bush, c. 1745.

From the seventeenth century on many harbour officials and custom officers lived in Ringsend. Most of them were English and members of the established church. As their way to the parish church in Donnybrook was often impassable because of the frequent floodings of the area by the Dodder, they applied for a chapel to be built near them. Their request was granted by King William III. After his death Queen Anne became the patron of the church. This made the church a Royal Chapel, and so its official name is ‘Royal Chapel of St Matthew’s in Ringsend’. Despite that name it is situated in Irishtown and will be described with that village.

Samuel Lewis5 describes Ringsend in 1837 as a small town. Revd Beaver H. Blacker quotes the 1851 census giving 2,064 inhabitants for Ringsend without Irishtown.6 In 1863 Ringsend had 1,931 inhabitants in 209 (often dilapidated) houses.7 The impression of a town might not only have come from the number of inhabitants, but would also have been boosted by the presence of the garrison in Pigeonhouse Fort, halfway along the South Wall nearby.

The Great South Wall, built in the second half of the eighteenth century, was the longest sea wall in Europe and still is one of the longest, though land reclamation hides that fact to some extent.

From the ‘Point’ of Ringsend, the South-wall extends into the bay 17,754 feet; nearly three English miles and an half. It was commenced in 1748, and finally completed in 1796; and is composed of blocks of mountain granite, strongly cemented, and strengthened with iron cramps. The breadth of the road to a strong artillery station called the Pigeon-house (which was erected near the close of the last century, and is 7,938 feet from Ringsend), is nearly forty feet at bottom, but narrows to twenty-eight feet at top; the whole rising five feet above high-water. There is a basin at the former place, 900 feet long by 450 broad, and a landing-place raised 200 feet broad, on which are several convenient wharfs, not but little frequented. The pier at this point is 250 feet wide; and on it are raised buildings, which were formerly used as a magazine, an arsenal, and a custom-house. In the channel between the Pigeon-house and the Light-house is the anchorage called Poolbeg (formerly denominated Cleer-rode, Clareroad, and Clarade) where vessels may lie in fifteen feet at low water. At the extremity of the Wall is the Light-house, commenced in 1761, and completed in 1768, under considerable difficulties, by Mr Smith.8

The nautical expression ‘cleer-rode’ today is hardly known by anybody who is not involved in shipping. The word is composed of two parts which in modern English would be ‘clear’ in the sense of ‘safe’ added to the nautical expression ‘road’ (compare French ‘rade’ and German ‘Reede’). A ‘road’ in this sense is a place where ships can anchor, though without shelter. As a nautical term this word is still used with the same meaning nowadays.

D’Alton described the South Wall in exactly the same words that Revd Blacker used, but D’Alton then goes on to explain the difficulties in building the lighthouse:

... from the depth of water, the raging of the seas, and the power of the winds in such an exposed situation. Those obstacles, however, were overcome by the skill of Mr Smyth, the architect, who collected vast rocks, and deposited them in a huge caissoon or chest, which was sunk to the bed of the sea, and afterwards guarded with a buttress of solid masonry, twenty-five feet broad at the base. On this the ingenious architect raised a beautiful circular structure, three stories high, surrounded by an octagonal lanthorn of eight windows.9

This lighthouse at the end of the Great South Wall replaced a former lightship that had shown the entrance to Dublin’s harbour since 1735.10 When the lighthouse was finished nearly two hundred and fifty years ago, it did not look like it does today.

This was the first lighthouse in the world to be illuminated by candlepower, and from 1786 on it was one of the first using spermaceti oil (a clear, yellowish liquid produced by the sperm whale) as lamp fuel. Hook Lighthouse in Co. Wexford changed to spermaceti oil five years later in 1791.

In the second half of the nineteenth century it was decided to secure the base of the lighthouse by laying reinforced concrete blocks around it. This work was done using the diving bell that the port engineer of that time, Bindon Blood Stoney, had introduced in 1860 for underwater port work.

This diving bell has been preserved and today (2017) can be inspected on Sir John Rogerson’s Quay.

First Poolbeg Lighthouse, finished 1768. (From N. Whittock, A Picturesque Guide Through Dublin (Dublin 1846))

Poolbeg Lighthouse and old crane.

Poolbeg Lighthouse now is electrified and automated. It used to have a foghorn as well, but this was switched off some years ago. Until then its booming sound told all inhabitants up to a few kilometres away that the visibility at sea was bad, even when it might have been a clear day on land. People living near it were not pleased, though, when it went off in the middle of the night.

The full length of the South Wall is more than five kilometres from the original start to the lighthouse at the tip. When the Poolbeg Peninsula was reclaimed from the sea, the new land made the wall look shorter. Because of modern land reclamation only a part of the original wall has water on both sides: the River Liffey on the left and the sea on the right when facing outwards.

Dublin citizens, for whom the South Wall was a favourite place for walks, had occasion to complain in 1766 that it was not very pleasing to walk there. In December 1765 or as other reports say on 4 March 1766, four men were hanged at the gallows that at that time was near Baggotrath Castle. What happened afterwards is explained by Gaskin:

The following note appears in all the Dublin papers of 9 March 1766:

The bodies of the four murderers and pirates – McKinley, St Quinton, Gidley, and Zekerman, were brought in the black cart from Newgate, and hung in chains, two of them near Mackarell’s Wharf, on the South Wall near Ringsend, and the other two about the Middle of the Piles, below the Pigeon House.

The bodies of the four pirates remained suspended on the wharf and at the Pigeon House till the month of March following. On 11 March, however, a letter appeared in Faulkner’s Journal, signed a ‘Freeholder’, complaining of the hoops which bound the bodies as being very imperfect. On referring to the same journal for 29 March I find the following:

The two pirates, Peter McKinley and George Gidley, who hang in chains on the South Wall for the murder of Captain Coghlan, etc., being very disagreeable to the citizens who walk there for amusement and health, are immediately to be put on Dalkey Island, for which purpose new irons are being made, those they hang in being faulty. Richard St Quintan and Andrea Zekerman, the other two concerned in this cruel affairs, are to remain on the Piles at the Pigeon House.’ Accordingly the same journal, on the 1st and 12th of April, 1767, announces the removal of the bodies, in deference to public opinion, from the new wall, and that they were carried by sea to the rock on the Muglins, near Dalkey Island, where a gibbet was erected and they were hung up in irons, said to be the completest ever made in the kingdom.11

At the end of the eighteenth century the packet boats went to and from Poolbeg Harbour, then partly protected by the South Wall. A Mr Pidgeon was employed as caretaker for a house built to store material that was used in the harbour. In due course Mr Pidgeon discovered that he could earn extra money by providing food for the passengers arriving and leaving, and for Dubliners just coming out for the day to watch whatever was happening. The house later turned into a hotel and the name changed to Pigeon. In 1813 the War Office bought Pigeon House Hotel, together with other buildings and the ground around them from the Harbour Commissioners for slightly more than £100,000 and built a fortress a short stretch west of the Half Moon Battery on the South Wall.12 When it finally dawned to the authorities that Napoleon would not attack Dublin and that even later in the nineteenth century nobody else had such ideas, the fortress was dismantled and sold to Dublin Corporation in 1897 for £65,000.13

Pigeon House Hotel is still there, though now it is neither a hotel, storeroom nor part of a fort. It is surrounded by industrial buildings and its distinctive back with the two semi-circular wings on either side is not easy to see. The guns are part of the few remains of the fort.

The Pigeon House Fort was planned to protect the harbour, but also to safeguard bullion and important documents. The only part left is the ruin of the entrance. It is not clear why the cannons that still exist aim towards the fort instead of away from it.

The remains of the entrance to Pigeon House Fort.

The South Wall used to house another institution: the Isolation Hospital. This had in 1903 replaced the Hospital Ship that had been anchored nearby since 1874. Both the hospital ship as well as the hospital were meant for treating people with cholera (and possibly other infectious diseases), thus removing them from town. Different sources mention a hospital in this area under the names: ‘Isolation Hospital’, ‘Cholera Hospital’, ‘Pigeon House Sanatorium’, ‘St. Catherine’s Hospital’, ‘Alan A. Ryan Home – Hospital for advanced cases’. They all seem to be the same place that is mentioned on the 1907 OS map as ‘Isolation Hospital’. The Pigeon House Sanatorium for patients with tuberculosis was part of the campaign of the Countess of Aberdeen, wife of the then Lord Lieutenant, who fought against this illness. Her hospital opened in 1907.14 This hospital, situated west of the electricity station and the sewage works, is described in the Environmental Appraisal of the Dublin Waste to Energy Project as St Catherine’s Hospital.15 One building of the 1907 complex is still extant. The former complex included a Roman Catholic chapel and a convent with other buildings. Those have disappeared. The modern yellow steel door in the wall shows the address ‘85c Pigeonhouse Road’. This is the address of a firm of analytical services.

RINGSEND HISTORY: THE VILLAGE

The first buildings of the village of Ringsend appeared east of the mouth of the Dodder (left on the photograph) and that is where the centre of Ringsend still is, even though it keeps changing.

In general the Grand Canal was and is regarded as the border between Pembroke, Dublin 4, and Dublin Inner City. At the Grand Canal Basin, however, the border originally ran along the middle of Barrow Street, leaving the warehouses on the canal outside Pembroke Township.

Grand Canal Basin is accessed from the mouth of the Liffey through three locks named (from west to east) Westmoreland Lock, Buckingham Lock and Camden Lock. The size of the locks increases from west to east. Nowadays only Camden Lock is still in use.

The road from the locks to Ringsend runs directly beside the Dodder and shows that the course of this still quite tempestuous river has been straightened. Much could be done in this area to make it into a nice little water side park.

The mouth of the Dodder, 2010.

Camden Lock at Grand Canal Dock.

Freshly painted Victorian letterbox in Ringsend.