16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

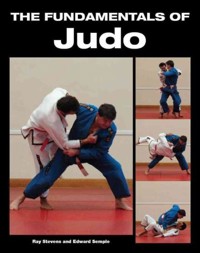

The Fundamentals of Judo identifies the essential techniques that define Judo as a fighting art and looks at how students should practise and develop these key skills. The core techniques are analysed in depth and through step-by-step photography for the benefit of both beginner and experienced Judo players. The analysis of each technique reflects Ray Stevens' detailed technical knowledge and experience as a Judo player.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF

Judo

Ray Stevens and Edward Semple

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2012 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Ray Stevens and Edward Semple 2012

Photographs © Patrick Jackson

Illustrations © Hilary Walker

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 918 6

CONTENTS

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Foreword

1

The History and Development of Judo

2

Getting Started

3

Throws (Tachi-Waza)

4

Groundwork (Ne-Waza)

5

Putting It All Together

Index

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to Elvis Gordon. May you rest in peace my friend.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors extend their sincere thanks to Hilary Walker who drew the illustrations to this book and proof read the text. Her input has simply been invaluable. Hilary’s website is a must for anyone who likes the illustrations in this book www.hilarywalker.co.uk. Hilary was given permission to observe and photograph a black belt training session at the Kodokan Dojo in Tokyo, Japan. The images she took away from that visit inspired the illustrations in this book. Patrick Jackson took the photos for the book and the authors would like to thank him for his incredible patience and support.

Photographs © Patrick Jacksonwww.patrickjacksonimages.com

Illustrations © Hilary Walker Illustrations by Hilary Walker are available for purchase as prints fromwww.hilarywalker.co.uk

FOREWORD

Among British judoka Ray Stevens stands out as one of those who have done more than most to make the sport of judo better known and accessible to a wide audience. His achievements in judo are well known: an Olympic Silver Medallist who has trained and competed successfully in many parts of the world, he is now Vice-Chairman of the London Area.

Ray’s passion for judo started at a young age when his focus and determination soon became apparent. Having had the privilege of observing his career over many years, I was delighted to learn that he had decided to present his skills, experience and judo insights in a new book. Ray is a popular and accomplished teacher and his fresh and engaging style, accompanied by his sound techniques, will appeal to beginners and the more experienced practitioner alike.

Judo is a sport that never stands still: as well as re-interpreting ideas from the past, it is always evolving, and I believe that this book will convey its fascination, variety and excitement to a new generation of readers.

Tony Sweeney, 9th Dan

CHAPTER 1

THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JUDO

Judo was developed from the Japanese martial art ju-jitsu at the turn of the twentieth century by Jigaro Kano. It is important, therefore, that any historical record of judo recognizes the essential role ju-jitsu played in the development of judo. Although both judo and ju-jitsu come from Japan, the origin of the techniques that define them both probably came from elsewhere.

Nearly all ancient cultures had some form of grappling or unarmed fighting but it was really the Greeks who had the first documented system of unarmed combat. From ancient Greece came Alexander the Great, who had conquered most of the world around 300 years before the birth of Christ, and he first introduced wrestling to India. Many believe that it was the technical changes made to wrestling in India around this time that led to the birth of ju-jitsu. There is certainly a strong similarity between the pinning and throwing techniques of ju-jitsu and those of Greco-Roman wrestling.

Most historians agree that the first documented system of unarmed combat to reach China came from India, along with Buddhism. How much influence Chinese culture had on Japan is impossible to say but clearly the early fighting techniques that came from India and that led to the development of kung fu must have had an influence on Japan. Although Japan at times has tried to limit its contact with the outside world, there is a rich history of trade and war between Japan and China. The Japanese principles and beliefs that were central to the development of sumo and ju-jitsu must have been influenced by events in China. Incredibly, many of these ancient principles and beliefs underpin judo practice today.

Many of the myths surrounding the creation of Japan talk of gods such as Bishman, the God of War, locked in unarmed combat with evil demons from the Underworld, such as Mikaboshi, fighting for power and supremacy. These early descriptions are often regarded as the first descriptions of sumo. Sumo certainly started as a form o wrestling designed to help warriors train for battle and was very different from the sumo seen on television today. There would have been a much greater range of techniques including kicks, punches, throws and locks. Sumo is widely regarded as an important influence in the development of ju-jitsu. It is from this early sumo that the origin of many of ju-jitsu’s grappling techniques can be traced.

What is clear is that over hundreds of years the Japanese developed and constantly refined a very sophisticated fighting system known as ju-jitsu. Much of how ju-jitsu developed inevitably reflects how Japan developed and changed as a country. This link between Japanese society and ju-jitsu is a central and important theme in the formation and development of judo. These stories and myths that surround the development of ju-jitsu and then judo are an important part of Japanese history. They reflect the social changes Japan was going through at that particular time. These two arts did not simply spring into existence: they evolved and developed because of very important social issues and principles in Japanese society. This is important because many of these issues and principles still shape and govern the sport of judo today. It is only by looking back at the history and development of ju-jitsu and Japan that we can understand the principles and beliefs that were so important to Jigaro Kano and the development of judo.

Ju-Jitsu

Early Japanese history is defined by conflict and war. From the beginning of records right through to and including the Middle Ages there was very little so cial stability. Japan was ruled by warlords who constantly fell in and out of alliances. War between these differing warlords was common and the skills of a good soldier (samurai) were much in demand. The chief skills of the samurai at this time were archery, riding and sword fighting.

Ju-jitsu techniques were your last option on the battlefield when you had no weapon or horse and you were up close to the enemy. In essence, ju-jitsu was unarmed combat. Sword fighting was the primary discipline of the warrior, but ju-jitsu would have been seen as a natural extension of sword fighting because grappling was a natural extension of what you had to do when swords met and you were up close to your enemy. Also, not all fights took place on the battlefield; many fights were in limited spaces such as in crowded marketplaces or narrow corridors where the use of a sword was not as effective. There were also certain social situations where the carrying of a sword was forbidden.

Essentially, ju-jitsu was technically comprised of strikes (kicks and punches), throws, strangles and locks. These techniques could be used to kill, maim or restrain, depending on the situation. Although the primary purpose was to train the warrior in hand-to-hand fighting, ju-jitsu would also have included the use of short weapons such as the knife. The knife in particular was a popular weapon of choice and seen as an ideal weapon for close-quarter fighting. This close-quarter fighting was what ju-jitsu was designed for, so ju-jitsu would have employed attacks and defences both with and against small weapons. Given the constant state of war between the rival warlords, these jujitsu skills were constantly refined and developed through generation after generation of samurai, and they developed over hundreds of years of constant war and conflict to a level of brutal effectiveness. Different samurai would have specialized in different ju-jitsu techniques depending on the role given to them by their warlord, resulting in the rise of the ninja, experts in stealth, assignation and murder.

While war defined the early development of ju-jitsu, it was ironically peace that defined the later development of ju-jitsu and eventually led to the birth of judo. After a long series of wars, Japan was unified under one ruling clan in 1603. To keep peace and stability a system of social control was introduced, which was so effective that there was peace for the next 250 years. This system of control worked because it effectively governed just about every aspect of Japanese life including the teaching and practice of ju-jitsu.

Society was divided into distinct groups, each governed by strict laws and regulations. The ruling elite were the samurai who enjoyed privileges the lower social groups, such as the peasants, did not. The samurai were allowed to carry a sword and had the right to kill anybody of another social group if they thought it necessary. However, there was also a clear hierarchy within the samurai group: the lower-ranked samurai were foot soldiers or clerks while the higher-ranked samurai were landed aristocrats or bureaucrats. Every aspect of their lives would have been governed by the laws and regulations that had been imposed upon Japanese society and, importantly, this would have included their education. The samurai were the only social group allowed to carry and use weapons so only they would have had to learn skills such as sword fighting and ju-jitsu. The other social groups such as the peasants or farmers would have had their own fighting techniques, in this case karate. Karate means ‘empty hand’, a reflection of the fact that this social group was not allowed to carry weapons. The weapons used in karate go back to the farming implements that the peasants/farmers were allowed to use for working on the land. Karate students today still train with weapons such as the bo, a long wooden staff, and the kama, a vicious cutting weapon based upon the sickle. This distinction is very important because the development of ju-jitsu and then judo was based upon the beliefs and principles of the samurai, the warrior class of Japanese society and, as such, a unique social group within that society.

A samurai’s education was compulsory. He would have had to learn and train regularly in different fighting skills such as the sword and ju-jitsu. However, a samurai was expected to be much more than just a warrior: he would have been expected to study other subjects such as literature and art. A samurai was expected to be highly skilled and educated. The training hall in which the samurai learnt these skills was the dojo, which was seen as a sacred place of learning. Here they learnt to develop the physical, mental and spiritual skills and the values essential to their role in Japanese society. The education the samurai received in the dojo was a well-rounded one and was as much about the development of the individual as the development of a skilled fighter. This would later be a central and guiding principle in the development of judo as well. Even in judo today we refer to the place we train in as the dojo. In judo classes all over the world the dojo is still seen as a special place of learning and education.

As this was now a period of social stability and peace, ju-jitsu began to change. This long period of peace meant that ju-jitsu was no longer needed on the battlefield and so was now primarily a form of unarmed combat taught and practised in the dojo. Ju-jitsu was the fighting art of the ruling elite. Still brutal and effective, it was also vital that the practice of ju-jitsu reflected the complex code of honour and etiquette so important to the Japanese ruling class of the time. As a result, the practice of ju-jitsu became much more formal and there was a strict code of conduct for all samurai when they learnt and practised ju-jitsu in the dojo. This code of conduct is still a fundamental part of modern judo practice. The formal bow to your opponent before you engage in combat is still as important in judo today as it was back then to the samurai warrior. The samurai code of respect, humility and decorum is still fundamental to the proper practice of judo.

This shift in ju-jitsu from battlefield to dojo also changed the martial art technically. The fighting techniques of ju-jitsu had primarily been designed for the chaos of the battlefield and an opponent dressed in armour. However, ju-jitsu was now primarily practised in a dojo, usually on mats, in bare feet against an opponent who wore loose-fitting clothes of cloth, and the fight was usually one on one. Ju-jitsu still technically consisted of strikes, strangles, locks, throws and the use of small weapons but the more controlled environment of the dojo allowed the development of a much greater range of techniques. Each dojo would have taught the same set of basic skills but each would also have favoured and emphasized certain techniques more than others. Which techniques were given the most importance depended entirely on what the individual master, who was the principle instructor at the dojo, thought were the most effective and important. This led to a proliferation of what is called different ‘styles’ of ju-jitsu. This distinction still exists today, with different styles being practised all over the world. Usually the style of ju-jitsu taught at a specific dojo stayed within the family, with the master passing both his role and style of ju-jitsu on to his son.

The master of each dojo would have to have been a skilled expert and able to put into practice what he taught. At any time, a master from another dojo could challenge him or any of his students to a fight, and students from each of the different dojos would have regularly fought one another in contests. There was also a well-known practice where samurai warriors would meet at certain known crossroads at night and take on anybody who wanted to fight. These fights had no rules: you won or you lost. It is interesting to note that these fights were similar in style to that of modern cage fighting. Each samurai warrior would have brought a wide range of technical fighting skills to the contest but each fighter would have had particular technical fighting skills that they specialized in. Some would have been better strikers (punches and kicks), others would have been better grapplers (locks, holds and throws) and some would have been better fighting on the ground than in the stand-up position. Each fighter would have tried to dominate the fight with his strengths and thereby expose the weaknesses of his opponent.

While each dojo may have taught different styles of jujitsu, all would have followed the ethical code of the samurai warrior, called budo or bushido, which defined what it meant to be a samurai warrior. The manner in which a samurai lived and died was very important. The beliefs and practices of Zen Buddhism were central to the samurai approach to life. Simplicity and a life free from the fear of death were core principles to being a good samurai. This is beautifully illustrated in the life of the samurai warrior Miyamoto Musashi, who lived in the early 1600s. Miyamoto Musashi believed that there was only one goal, victory, and that there was no other point to combat. He was a master swordsman and travelled Japan challenging different masters from all over the country to fight. He died at the age of sixty, undefeated. Not only was he an exceptional swordsman but, like all samurai, he was very well educated. Thanks to his samurai education, he was not only a skilled fighter but also an accomplished painter, poet and sculptor. He believed that hard work, simplicity and discipline were essential if you were to learn and that only a life of loyalty, duty and honour was worth living. Only a life well lived prepared you for death. It is only when you understand the importance of these values to the Japanese samurai that you can comprehend how vital etiquette, manners and honour were to the proper practice of ju-jitsu. Much of the later success of judo both in Japan and abroad was due to the fact that judo has tried to retain many of these values and practices.

Gradually Japanese society began to change: the four-class system declined and was eventually abolished. This was particularly hard for the samurai warriors because they no longer enjoyed the special status and privileges that had been their preserve for so long. Japan was no longer so insular and wanted more international trade. To do so, Japan began to modernize and one of the key areas to change fundamentally was the Japanese education system. The Japanese ruling elite still believed in the values and principles that defined what it was to be a samurai, but now the general belief was that all Japanese men and women should follow the ethical code of the samurai warrior. The values and principles of budo or bushido should not just be for one particular section of Japanese society but for the whole of Japan. This would result in Japan becoming stronger as a country and therefore more competitive and successful on the international stage.

It was these changes in the education system that gave Jigaro Kano, the founder of judo, the opportunity to develop and promote judo. He used the core values and practices of ju-jitsu as the fundamental basis of judo because these were the very qualities that he wanted to develop and promote in the young men and women of Japan. Jigaro Kano represented everything that was new about Japan and how the country was changing. He developed judo as a way to teach, promote and spread the values and principles of budo or bushido to all social classes both in Japan and abroad.

Jigaro Kano

Jigaro Kano is the founding father of judo. It was his vision to take ju-jitsu and remould it into a sport that would be better suited to a more modern Japanese society. In doing so he created something that in a little more than 100 years has evolved from a small personal project in a small hall to an international sport that has a rich Olympic history – an incredible journey by any standards.

Jigaro Kano was born in 1860 in the city of Kobe. His father worked in Tokyo for the government and had strong links with both the Imperial household and the government. The Kano family was part of Japan’s ruling class, and the importance of these social connections to Jigaro Kano when he later wanted to promote judo both in Japan and abroad cannot be underestimated.

In 1870, Jigaro Kano’s mother died when he was just ten years old. The young Jigaro therefore went to live with his father in Tokyo where he received a first-class education. He was very bright and at the age of fifteen he was enrolled at the foreign language school in Tokyo. Jigaro Kano’s ability in foreign languages was exceptional and he learnt to write fluently in English. These skills would be important when he later started to promote judo outside Japan and work towards getting judo accepted into the Olympic Games.

In 1877, aged eighteen, Jigaro Kano went to Tokyo University to study political science, economics and education for four years. His studies there left him with a passion for education that would define the rest of his life. He believed that a good education was the foundation stone to a well-balanced and successful society. His belief in the importance of education would have been a popular and widely held view in Japan at this time. Japan for the first time in several hundred years was looking outwards to other countries and now wanted to compete on the world stage and trade with countries such as Britain, America and Russia. A good education system was vital if Japan was to adapt to this new, competitive world. Japan wanted to modernize her education system and it was well-educated men such as Jigaro Kano who would help define and shape this. Jigaro Kano, with his founding of judo, was very much in the right place at the right time.

Jigaro Kano considered education to have essentially three main components:

•

Knowledge, meaning the technical detail a student needed to learn for a subject.

•

Ethics, meaning the moral values a student should learn.

•

Health and fitness, meaning the training of the body as well as areas such as diet and hygiene.

This definition of what a good education should comprise would have been very much in tune with Japanese thinking. The Japanese had always put great value in knowledge and the application of sound technical principles. This can be seen throughout history in Japanese architecture and art, which are usually exquisite in detail. The education of the samurai had focused on an honourable life, and the value of virtues such as honesty and simplicity. These were values that the ruling class of Japan still held dear in principle and would have wanted to continue as the focus of any new education system. Health and fitness were vital components to being a productive member of Japanese society. The education of the samurai had encompassed both mind and body and both were important in the individual’s education and development. Clean, healthy living was a prerequisite to creating the right environment for learning and personal development. It is no accident that the structure of judo in Japan was built upon these guiding principles.

When Jigaro Kano went to study at Tokyo University he also began studying ju-jitsu. Quite why he decided to take up ju-jitsu at this time is somewhat of a mystery. There are stories that he started to learn ju-jitsu because he was being bullied at school and wanted to learn how to defend himself. I am not so sure this is correct. Jigaro Kano was now eighteen years old and had just left school; he was embarking on what was a new chapter in his life. Problems at school, if they did exist, would have been left behind. This was a new beginning and I think it much more likely that Jigaro Kano, like any young man, wanted to try new and different things. Ju-jitsu was part of Japanese history and the educated samurai warrior class. It is much more likely that it was these influences that first attracted him to ju-jitsu.

Records are contradictory as to the style of ju-jitsu Jigaro Kano may have learnt and whom he learnt his jujitsu from; what is clear is that he studied ju-jitsu for only four years. He left Tokyo University in 1882 at the age of twenty-two and accepted a teaching job at the Peers school. The Peers school was held in very high regard and Jigaro Kano would have taught the children of the most powerful and influential families in Japan. The social connections he made here, coupled with those of his family, were to be very important to the later success of judo.

When he accepted his new teaching post, he set up his own ju-jitsu school and called his style of ju-jitsu, judo. His dojo was called the Kodokan, had nine students and an area of just 22sq m (26sq yd) to train in. This was an extraordinary step for the young and inexperienced Jigaro Kano to take and it tells us much about his confidence and ability to understand how Japan was changing. The masters who taught ju-jitsu at this time quite literally devoted their lives to their own style of ju-jitsu. Their technical knowledge and skill were acquired over decades, not months and years. After just four years of study, Jigaro Kano could not have had the technical skills or knowledge to regard himself as a particularly skilled fighter or gifted teacher of ju-jitsu. He set up the Kodokan and started to teach judo because he wanted to take ju-jitsu in a different direction. His vision was to marry the practice of ju-jitsu with his other great passion in life, education. At the Kodokan there was not only judo practice but also lectures on a wide range of topics such as physiology, diet and hygiene. The Kodokan was based upon the two defining themes of Jigaro Kano’s life: education and the practice of judo.

Judo

Technically, Jigaro Kano struggled at first to convince anyone that judo was really any different from any other style of ju-jitsu in Japan. Indeed, the technical differences between ju-jitsu and judo would have been very small in the beginning. The system of techniques that helped define judo evolved over time. It was not until 1887 that the core techniques of judo could be defined in what we would today regard as some kind of syllabus. After establishing the Kodokan dojo, Jigaro Kano kept on developing and refining the technical elements of judo, a process that in many ways has never stopped. For judo is not a fixed set of skills and even today the technical side of judo is constantly changing and developing.

To Jigaro Kano sport was a vital part of a proper physical education and therefore a central component to a well-balanced education. He may have struggled at first to separate ju-jitsu and judo technically but it is the greater emphasis that judo placed upon being a sport that separated ju-jitsu and judo right from the start. Judo had three principle objectives:

1.

Combat.

2.

Moral education.

3.

Physical education.

The first two objectives are very similar to those of ju-jitsu, but not the third. The idea of transforming ju-jitsu into a sport was new and visionary and allowed judo to develop and grow with the social changes that Japan was going through at the turn of the twentieth century.

Jigaro Kano must have been profoundly influenced by what was happening in America and Europe at that time. Physical education and sport were undergoing huge changes and becoming ever more popular in the West. It would not be long before the Olympic movement began to take shape and launch so many different sports on to the international stage. In developing judo as a form of physical education and a competitive sport, Jigaro Kano would have used developments abroad as his model and inspiration. By taking ju-jitsu as his starting point, he developed a sport that was relevant to Japan, a sport that reflected important Japanese customs, values and beliefs. However, his approach was new and different and reflected how sport was developing abroad. This would be fundamental to the success of judo not only in Japan but all over the world.

To make judo into a sport, Jigaro Kano banned the more dangerous techniques in ju-jitsu. This meant that the practice of judo was relatively safe and a very effective form of exercise in developing and improving general levels of fitness. Judo allowed students to practice a sport they enjoyed and in the process get very fit and strong. Judo was and is a more limited form of ju-jitsu and these limitations make the practice of judo safer but importantly still preserve judo as an effective form of combat. These qualities can probably be most clearly seen in the practice of randori. Randori is essentially where students fight one another but under a strict set of rules, the rules that define judo as a sport. These fights were much safer than the norules contests of ju-jitsu but still very realistic. This meant that students of judo sustained far fewer injuries than those of ju-jitsu but still had the technical abilities to defend themselves.

Jigaro Kano established the Kodokan dojo at just the right time because Japan was ready for the formation and development of a sporting form of ju-jitsu. What he cannot have expected was that the rest of the world was also ready for a sporting form of ju-jitsu as well. The success and expansion of his Kodokan dojo mirror the success and expansion of judo at first in Japan and then abroad. The dojo grew from a 22sq m (26sq yd) training area in 1882, to 197sq m (236sq yd) in 1893, to 378sq m (452sq yd) in 1906 and to 933sq m (1,116sq yd) in 1934. In 1984, the Kodokan dojo was completely rebuilt with a fantastic training area, accommodation and a museum. What started as a small training area with nine students was within 100 years the centre for an international sport that was part of the Olympics.