Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

How would your career, social life, family ties, carbon footprint and mental health be affected if you could not leave the city where you live? Artist Ellie Harrison sparked a fast-and-furious debate about class, capitalism, art, education and much more, when news of her year-long project The Glasgow Effect went viral at the start of 2016. Named after the term used to describe Glasgow's mysteriously poor public health and funded to the tune of £15,000 by Creative Scotland, this controversial 'durational performance' centred on a simple proposition – that the artist would refuse to travel beyond Glasgow's city limits, or use any vehicles except her bike, for a whole calendar year.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 692

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

I will not travel beyond Glasgow’s city limits, or use any vehicles except my bike, for a whole calendar year. – Ellie Harrison, January 2016

This simple proposition – to attempt to live a ‘low-carbon lifestyle of the future’ – put forward by an English artist living in post-industrial Glasgow cut to the heart of the unequal world we have created. A world in which some live transient and disconnected existences within a global ‘knowledge economy’ racking up huge carbon footprints as they chase work around the world, whilst others, trapped in a cycle of poverty caused by deindustrialisation and the lack of local opportunities, cannot even afford the bus fare into town. We’re all equally miserable. Isn’t it time we rethought the way we live our lives?

In this, her first book, Ellie Harrison traces her own life’s trajectory to examine the relationship between literal and social mobility; between class and carbon footprint. From the personal to the political, she uses experiences and knowledge gained in Glasgow in 2016 and beyond, together with the ideas of Patrick Geddes – who coined the phrase ‘Think Global, Act Local’ in 1915, economist EF Schumacher who made the case for localism in Small is Beautiful in 1973, and the Fearless Cities movement of today, to put forward her own vision for ‘the sustainable city of the future’, in which we can all live happy, healthy and creative lives.

ELLIE HARRISON was born in the London borough of Ealing in 1979. She moved north to study Fine Art at Nottingham Trent University in 1998. In 2008 she continued northwards to do a Masters at Glasgow School of Art and has been living in Glasgow ever since. She has previously described herself as an artist and activist, and as ‘a political refugee escaped from the Tory strongholds of Southern England’. In 2009 she founded Bring Back British Rail, the national campaign for the public ownership of our railways. As a result of thinking globally and acting locally during The Glasgow Effect in 2016, she is now involved in several local projects and campaigns aimed at making Glasgow a more equal, sustainable and connected city.

First published 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-64-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Martins the Printer Ltd, Berwick-upon-Tweed

Typeset in 10.4 point Sabon by Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Front cover illustration by Neil Scott, Glasgow

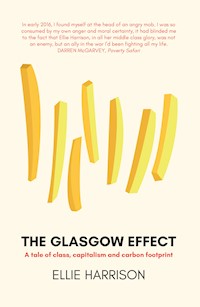

Photograph on back cover taken by Ellie Harrison on 28 October 2015, featuring chips bought and eaten by the artist (at her own personal expense) from the Philadelphia chippy, Great Western Road.

Cover design by Neil Scott, Ellie Harrison and Maia Gentle

Discussion notes and further information about the artworks referenced in this book can be found at www.ellieharrison.com/book

© Ellie Harrison 2019

For my beautiful mum

Extract from ‘Neoliberalism’ by Loki

Since the youngest age I was always threatening to run away,

but social mobility isnae what they say.

Stuck at a red light on my tricycle thinking ‘fuck them!’

While a bunch of Westenders whizz past me in the bus lane.

How come it’s bright in this posh part, but in Pollok it’s dark?

Probably cos the sun isnae shining out of everyone’s arse.

Vegan liberals lecture me to ‘buy local’,

while they’re sneering at the Glesga dialect and my vocals.

…

Apart fae that, nothing’s going on here locally,

Except an off sales masquerading as a grocery.

The local shops are shutting since the new Tesco’s getting built.

Thought I’d check it out. Went in sceptical,

had to walk 20 miles just to get some bread and milk.

Then got diverted at the checkout by a clothing section.

Ended up flipping out, bought some pens, Pepsi, Lilt,

a Craftmatic adjustable bed, a lamp, a feather quilt,

a pair of stilettos, salt and pepper, a kilt, a pair of stilts.

First person to mention my free will is getting killed.

Luckily there’s a pretty woman on the end of the till,

offering me instant loans to help me with my credit bills.

…

While I look across the river at you sipping your Pimms,

wishing I could get hooked on yoga, swimming and gyms,

as I can to chicken dippers, Lidl’s crisps and 70 million minute SIMS.1

Reproduced with permission of Darren McGarvey (aka Loki the Scottish Rapper)

Contents

Extract from ‘Neoliberalism’ by Loki

Preface

Introduction

PART 1A BRIEF HISTORY OF NEOLIBERALISM

Chapter 1 Thatcher’s Children

Straight outta Compton

What the fuck is neoliberalism?

Privatisation

Deregulation

Trade liberalisation

Social mobility isnae what they say

Waste not, want not

Major setback

Chapter 2 Creative Decade

Things can only get better

The knowledge economy

A golden age

Technologies of the self

Community vs career

Chapter 3 Welcome to Scotland

Dark clouds

Creative education

Bring Back British Rail

Hedonism vs asceticism

Austerity politics

Long-distance love

Reality check

Chapter 4 Socialist Dystopia

Turning point

You are what you eat

System change, not climate change

Asceticism and the spirit of capitalism

Compromise and complicity are the new original sins

Progress trap

The leaky bucket

Worst inequalities in Western Europe

Settlers and colonists

First as tragedy, then as farce

Carbon graph

PART 2THE GLASGOW EFFECT

Chapter 5 When the Chips Hit the Fan

Calm before the storm

I like Glasgow and Glasgow likes me

Facebook wormhole

The Divide

Small is Beautiful

Could there be a worse insult?

Chapter 6 Creative Destruction

But is it art?

Money can’t buy you love

Every human being is an artist

I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!

Career suicide

Where art and politics become one

Public property

Chapter 7 Lived Reality

Low-carbon lifestyle of the future

Citizen’s Basic Income

Biographic solutions to systemic contradictions

History, politics and vulnerability

Overcrowding

Rip it up and start again

Brain drain

Hypocrisy kills

Other causes of ‘the Glasgow effect’

Diseases of despair

The elephant in the room

Remunicipalisation!

Reflection and action

We need to stop ‘researching’ and start fighting!

Practising what we preach, preaching what we practise

Thrift radiates happiness

Hostile environments

The outsiders

Chapter 8 Aftershock

The end is the beginning

Impact agenda

The report

Homecoming

Worst nightmare

PART 3THE SUSTAINABLE CITY OF THE FUTURE

Chapter 9 Think Global

Climate emergency

Downward mobility

Back to the future

Prosperity without growth

Deconsumerisation

Chapter 10 Act Local

City as a site for social change

Regional power

Community control

Fearless Cities

Non-material pathways out of poverty

World-class public transport

Sharing is more sustainable

Motivational structures and meaningful work

Variety is the spice of life

Chapter 11 Universal Luxurious Services

Those things we all need to live happily and well

Information

Transport

Food

Healthcare

Housing

Co-production

Foundational economy

Public luxury

Localism and protectionism

Positive alternatives

Car-free future

Chapter 12 Travelling Without Moving

Equalising mobility

Minimising migration

Paradox of repopulation

Education for life, not for work

Rekindling our radical past

Love-hate relationship with the city

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

Preface

I STARTED TO write this book – for therapy, for clarity, for closure – in summer 2018, having been thinking about it for nearly a year. There seemed a beautiful symmetry in it being exactly 30 years since I first visited Glasgow, exactly 20 since I left my family home in Ealing and exactly ten since I moved to Glasgow to live; a good point to stop and reflect. My aim was to have it finished before I turned 40 in March 2019, a task in which I almost succeeded (it went to print on 29 July 2019).

The one thing nobody seemed to consider at the time The Glasgow Effect ‘chips hit the fan’ in January 2016, was that this was a project that could only have been dreamt up by a single woman in her late 30s, a ‘mid-life crisis’ you could say. I had chosen a title addressing mortality because it was, and still is, a major preoccupation. I loved my family and wanted to be nearer to them and I was angry at an economic system which had torn us apart; arbitrarily scattering us in different parts of the British Isles.

When nearly all my heterosexual friends and family were ‘settling down’ with a house, a car, a big telly, the latest smartphone, frequent holidays and some kids, I had a niggling feeling these lifestyles were neither ethical nor sustainable. I found myself resisting conforming to this social norm. Instead, I decided to devote my life to work, to undertake the most epic and the most public artwork of my career; one that did not only last a year, but which has shaped my thinking, action and life course ever since.

Reading Darren McGarvey’s Poverty Safari in March and April 2018 inspired me to start writing. His book, in turn, had been partly inspired by The Glasgow Effect project. As I sat alone, late at night, turning page after page, I came to realise the intimate connection a book enables between author and reader, away from the inherent agitation of the computer screen. A book demands patience to allow a person’s stories and ideas to unfold slowly over time, offering a more complete picture of how their personal history and lived experience have shaped their politics; their thinking and action in the world. From very different backgrounds, Darren McGarvey and I have arrived at similar critiques of the city, the society and the economic system within which we live.

I can’t say that this book has been an easy undertaking, but it was a necessary one. I have emerged stronger and with more conviction than ever that in order to address the ‘climate emergency’ we must urgently reduce the amount we travel and the amount of energy we consume. Not least because a happy, healthy and sustainable life can and should result from committing and contributing to the community where you live.

Ellie Harrison

July 2019

Ellie Harrison (right, aged nine), with her sister (left, aged ten), at Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988. (Family photograph)

Introduction

I FIRST CAME to Glasgow 30 years ago, in summer 1988 when I was nine years old. Margaret Thatcher had had a plan. Her government thought that by imposing ‘Garden Festivals’ and the associated twee middle-class values onto five of Britain’s most deprived post-industrial cities, she could miraculously raise the standard of living for everyone. It was symbolic of how her vision of ‘trickle-down economics’ was meant to work. You only need look at vast swathes of derelict and vacant land still left in Glasgow (9 per cent of the city),2 including much still around the ‘Festival Park’, and at Glasgow’s persistent and worsening inequalities of wealth and health, to judge this policy’s effectiveness. What it did succeed in, however, was luring more middle-class cultural tourists on ‘city breaks’ to see the sights and spend their money. And this was indeed why my family came.

My memories of the trip are hazy. I remember having a ‘Coke float’ in Deep Pan Pizza Co. somewhere in the city centre (which I now assume was Sauchiehall Street, though Deep Pan Pizza Co. has long-since gone bust).3 I remember this weird reconstructed house thing (which must have been the Mackintosh House at the Hunterian, completed in 1981). I remember the thrill of riding to and from the West End on the newly refurbished Glasgow Subway (public transport got me excited back then too). And, I remember I wasn’t allowed on the Coca-Cola branded rollercoaster because I was too short. That was it. The holiday was over. Armed with our Garden Festival merchandise (my sister had the t-shirt and I had the keyring, which we both still have – how’s that for ‘legacy’?), we returned to suburban London to tell teacher about our trip. I had no cause to return to Glasgow for another 20 years. And once again, it was ‘culture’ that led me back.

Glasgow’s Garden Festival could be seen as the beginning of the city’s post-industrial renaissance as a global capital of culture. It was promptly followed by Glasgow being awarded the mantle of European City of Culture in 1990, and a slew of investment in the arts sector: Tramway opened in 1990, the Gallery of Modern Art in 1996, The Lighthouse in 1999 when Glasgow was named UK City of Architecture, and the newly refurbished cca: Centre for Contemporary Arts in 2001.

The city had many high-profile artists nominated for Britain’s Turner Prize, which led the international star curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist to ‘parachute in’ one day in 1996 and proclaim all this as ‘the Glasgow miracle’.4 What I only came to realise after five years of living in the city myself, in 2013, was that this ‘miracle’ was much more about how the city appeared to people living elsewhere – to potential tourists, students or other transient residents – than it was about the quality of life for the majority of Glasgow’s citizens.

‘Glasgow is kind. Glasgow is cruel’, wrote Scottish novelist William McIlvanney in 1987.5 And so this book is about my love-hate relationship with this city, where I have now lived for well over a decade. It is my story. It is about how I ended up here, by following the absurd and lonely career trajectory of the ‘conceptual artist’. It aims to do what much of my art work has done before – that is to use my own personal history and lived experience to illustrate the impact that social, economic and political systems at local, national and global scales have on our individual day-to-day lives. Specifically it’s about the forces of globalisation, unleashed by Thatcher and her fellow free-market ideologues in the ’80s, which decimated industrial cities across Britain and sent millions of ‘economic migrants’ like me on the move. It could be about any post-industrial city attempting to fill the vast voids and regenerate its economy with ‘culture’, but it’s not. It’s about Glasgow and Glasgow, as we know, is special.

The phrase ‘the Glasgow effect’ began to emerge in the field of public health around the time I moved to the city in 2008. It was used to describe a then unsolved mystery. Why did people die younger in Glasgow than in similar post-industrial cities in England, such as Liverpool and Manchester? Why did Glasgow and West Central Scotland have the lowest life expectancy in Western Europe? In 2011, Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) published a report exploring 17 different hypotheses for why this could be, including: diet, other ‘health behaviours’ (such as alcohol and smoking) and ‘individual values’, ‘boundlessness and alienation’, lower ‘social capital’, a ‘culture of limited social mobility’, inequalities, deindustrialisation, ‘political attack’ and, of course, our terrible weather.6

GCPH concluded their 2011 report by saying that ‘further research is required to fully understand why mortality is higher’ in Glasgow.7 It wasn’t until May 2016, when they published their epic follow-up History, Politics & Vulnerability: Explaining Excess Mortality in Scotland & Glasgow,8 which synthesises research into 40 potential causes, that they finally claimed to have solved the mystery of ‘the Glasgow effect’ (their findings are discussed in detail in Chapter 7). By then, I was five months into my year-long ‘durational performance’ named after this phenomenon, which had become one of the most controversial publicly-funded artworks that Scotland had ever seen.

Part psychological experiment, part protest, part strike, for the whole of that year, I had vowed not to travel beyond Glasgow’s city limits, or use any vehicles except my bike. As stated in the application I submitted to Creative Scotland in summer 2015 to fund the project, my aim was ‘to actively address the contradictions and compromises’ which had been building in my own lifestyle ‘as my career as an artist/academic has progressed’ and to slash my own carbon footprint for transport to zero (the results can be seen in my Carbon Graph on pages 138–9).9

I had chosen the title The Glasgow Effect to dismantle the myth of ‘the Glasgow miracle’,10 and to throw the spotlight back on the real story of this city – glossed over in recent years with a pervasive ‘People Make Glasgow’ pr exercise – where a third of children live in relative poverty,11 and 20 per cent of our households use food banks.12 Sacrificing myself to the social media trolls as a symbol of the detached ‘liberal elite’ I too had come to despise, I aimed to encourage people to make the connections between the social, environmental and economic injustices in our world, and to realise the need to fight for holistic solutions – at an individual and policy level – which address all three at once.

As Darren McGarvey acknowledges at the end of Poverty Safari that during The Glasgow Effect I was not just researching and criticising, I was actually doing; through my action that year and the way I had chosen to live, I was articulating

what might come next… beginning to reimagine the society that had left so many in [his] community feeling excluded, apathetic and chronically ill.13

By undertaking The Glasgow Effect, I aimed to find out what happens if you make a stand against the forces of globalisation by localising your existence; what happens if you attempt to live a ‘low-carbon lifestyle of the future’ in a city, in a society and in an economic system with infrastructure and values still stuck in a carbon-intensive past (this is described in Chapter 7). Two years on from that intense and stressful experience and 30 since my first visit to Glasgow in 1988, this book aims to bring together everything I have learnt in order to provide the complete context for my thinking and action, which was lost in the whirlwind of the social media storm (a whirlwind described in Chapter 5).

The book is structured in three parts, each part containing four chapters. Part 1 – A Brief History of Neoliberalism – provides the backstory: a personal and political history examining the way our lives are shaped by wider social and economic forces often beyond our knowledge or control, and by the privileges or disadvantages that result from a person’s accident of birth.14Part 2 offers a behind-the-scenes insight into the making of The Glasgow Effect – exploring the many issues the project raised, including the relationship between art, activism and well-being. Part 3 sketches out a manifesto for The Sustainable City of the Future, articulating the action necessary to transform Glasgow and our other cities into places where we can all live happy, healthy and creative lives.

Part 1

A Brief History of Neoliberalism

CHAPTER 1

Thatcher’s Children

Straight outta Compton

NONE OF US choose where or when we are born. It just so happens that my life began in the now bulldozed Perivale Maternity Hospital in the London borough of Ealing in March 1979.1 It was the spring following the so-called ‘Winter of Discontent’, which saw the coldest weather for nearly two decades coupled with the largest strike action in Britain since the General Strike of 1926.2 In the absence of refuse collections, London’s Leicester Square was used as a makeshift landfill site. It was just a few days after the first contested referendum on the devolution of power from Westminster to Scotland and Wales (although it wasn’t until I moved to Scotland myself that I discovered that history). But, perhaps most symbolically for this story, it was less than two months before Margaret Thatcher came to power on 3 May 1979.

My mum and dad had been married for just two years, and I was brought home along with my big sister to a semi-detached house in West Ealing with its ‘own back and front door’,3 which they had bought for £18,750 in 1977. My parents had met at work in the early ’70s, where they both taught new-fangled subjects to teenagers – my mum taught ‘Communication Studies’ (as well as English and French) and my dad taught ‘Business’ at Uxbridge Technical College, opened in 1965. It was quite a handful having two children just 18 months apart, so for the first few years of my life, my mum stayed at home to look after us and get more involved in our local community.

I have happy memories of those very early days; sitting on the living room floor eating tasty snacks and watching telly. In between Chock-A-Block, Pigeon Street and Button Moon, I remember seeing glimpses of this powerful looking woman on the news. She had quaffed blond hair and was wearing a bright thatcher’s children blue suit. I didn’t really know what she was up to at that time, but what I did know was the more I appeared to be in awe of her, the angrier my mum would get.

My mum was born in Bickley in south-east London in March 1944, where she had to be sheltered from the air raids during the last year of the Second World War. Her parents were both Welsh. She had one Scottish grandmother (who was actually half-Irish) and despite having a booming posh southerner’s accent, it remained her pet hate to be mistaken as ‘English’ (could there be a worse insult?). She had always voted Labour. She was active in the teachers’ union,4 and when we were young she got involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the Ealing Peace Register. I have one very early memory of being taken on a coach trip. Together with a big group of families and children wearing a hotchpotch of ’70s styles, we were driven out of the city to a very crowded and very muddy field. While we all scampered about amongst the trees eating homemade sandwiches from foil wrappers, the adults just stood around. It was as though they were in a very long queue which didn’t seem to be going anywhere. It turns out that was Greenham Common, the peace camp set up and run by women in protest against the Cruise missiles being held at the Royal Air Force base in Berkshire during the Cold War.

In the early ’80s, my mum also joined the local branch of the Campaign for the Advancement of State Education (CASE), which sought to abolish selective schools and to ensure the same well-resourced comprehensive education was available to all children no matter where in the country they grew up. The campaign is still going – battling against the ‘academisation’ process in England, which under the mantra of ‘choice’ is ensuring the exact opposite. case also ‘rejects the hierarchical division of skills into academic and vocational subjects and affirms that well-educated children need both mental and practical skills’.5 Needless to say, my mum was always very supportive of all our skills and abilities – arts, sports and/or academic – and we were bundled off to the local state schools to make friends with local kids. It would not be a lie to say I was ‘straight outta Compton’ – attending Compton First School (1983–7) and Gurnell Middle School (1987–91), which both shut down in 1993.

It’s impossible to understand the nuances of the British class system when you’re not yet into double digits but I was aware there were kids at school from very different backgrounds. Ealing was one of the most ethnically diverse of all London’s boroughs and these schools served the big council estate, Copley Close, which was right next door – literally the other side of the railway tracks at Castle Bar Park. I remember being taken to birthday parties in my friend’s flats on the estate. Holding my mum’s hand, we’d navigate the dark stairwells and balconies. I was surprised at how cramped their living rooms were. That’s weird, I thought, how come the kids from Copley Close always have the most expensive trainers? There was racism and homophobia in the playground and I’ll never forget the bollocking I got when I repeated one of the words I’d picked up to my mum when I got home.

In 1987, the AIDS advert featuring that monolithic grey tombstone hit the telly. It said ‘there is now a danger that has become a threat to us all: it is a deadly disease and there is no known cure’. We were all terrified of catching it. Kids calmed their nerves by chasing others around playing ‘it’, as though they were passing this mysterious disease onto one another. Another popular insult in those days was ‘NHS’. If you had ‘NHS specs’, then it meant that they were free or cheap, whatever: they were the worst. So much of this must have been filtering down via parents from a right-wing media hell-bent on discrediting our public services and propagating hate to enable our Conservative leaders to ‘divide and rule’.

Compton and Gurnell were both secular schools. In fact, we were barred from singing anything religious. Our teachers had to be imaginative in assembly. Instead we ended up reciting pop hits from the ’60s: ‘Downtown’ and ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ (the drug references were lost on us of course), as well as ‘Guantanamera’ based on the poem by Cuban revolutionary philosopher, José Martí. Most of it went over our heads. We sang songs reflecting our diversity like ‘Linstead Market’, which we learnt in Jamaican Patois. I still know nearly all the words. We had a brilliant teacher called Mr Strong, who wrote our school thatcher’s children anthem ‘Gurnell Middle’s Happy Song’, and helped us put on plays which he wrote and directed. I was cast in the lead role as Wally Bottle, a small boy on a mission to clean up the planet. He lived in a landfill site and his best friend was a crisp packet. It was quite ahead of its time. The following year, I was cast as Scrooge! I don’t remember being any good at acting. All I remember is the feeling of being on a stage with everyone looking at me expectantly and not being able to perform quite in the way I wanted.

One day Gurnell had a visitor. It was the Conservative mp for Ealing North, Harry Greenway, who was also one of our school governors. He was later caught up in allegations of Tory ‘sleaze’ in the early ’90s.6 I had a feeling he was a nasty piece of work. He stood at the front of assembly and lectured us, then the head teacher asked: ‘Right, does anyone have any questions?’ Sitting cross-legged on the floor in the front row, I felt my pulse start to quicken. I had to say something, so I tentatively put my hand up. Harry Greenway spotted me: ‘Yes, that little boy at the front’. I was so humiliated. I forgot my question, but I did answer back: ‘I’m not a boy, I’m a girl!’ I was traumatised by that and many similar incidents around the time. In the year before I went to high school, I started to grow my hair into a drab ponytail which allowed me to just blend in. Little did I know that Harry Greenway’s Tory government were effectively eradicating difference and enforcing conformity anyway – their Local Government Act 1988 included the infamous ‘Section 28’ (known as ‘Section 2A’ in Scotland) banning discussion of homosexuality in any state school. The Act remained in force until 2000 in Scotland and 2003 in England and Wales. By then I was 24 and had left education altogether. I’d finally cut my hair short again.

My favourite book in the ’80s was Gertie & Gus.7 My mum used to read it to me in bed, and in later years we entertained ourselves by subjecting it to a Marxist analysis together. It tells the story of two happily married bears named Gertie and Gus. They live in a very modest little hut by the sea. Gus is a fisherman. Every day he heads out on his little boat bobbing around with a single rod to catch a fish for them both to have for tea. One day

Gertie has an idea: why doesn’t Gus catch a few more fish and then we could sell them and make a bit of money? So Gus works harder. He brings home bucket-loads of fish and they begin accumulating funds. Gertie buys him a bigger boat and hires some other bears to help him. They catch so much fish that they move out of the hut and into a posh villa and start buying fancier and fancier clothes – Gus wears a Captain’s uniform with gold epaulettes. But something isn’t right. It’s just not the same as ‘the good old days’ – when they caught and cooked their own dinner and actually had time to spend with each other and enjoy the beautiful scenery where they lived. They were so much happier then. So they gave it all up and went home.

What the fuck is neoliberalism?8

It took me nearly 30 years to work out what that woman on the telly was really up to and then the next ten to start fighting back. The aim of this book is to share all the things I’ve learnt during that time in the hope of inspiring young people to join the fight against an unjust system which has already robbed them of so much. I chose to include Darren McGarvey’s (aka Loki the Scottish Rapper) piece ‘Neoliberalism’ at the start as it touches on many of the book’s themes. The word ‘neoliberalism’ is often bandied around to explain why we live in such a precarious, exploitative and unequal world, yet it is rarely defined. I’m sure that’s what Loki is hinting at by using it as a title; another little jab at the pretension of what he calls the ‘progressive left’.

To understand the significance of the neoliberal policy decisions of the ’80s and ’90s to the world we live in today, it feels important to start with a clear definition. In simplest terms the word ‘neoliberalism’ breaks down into ‘neo’ (from the Greek for ‘new’) and ‘liberalism’ referring back to the ‘liberal’ economists in the early part of the Industrial Revolution who first theorised the so-called ‘free-market’. For example, the University of Glasgow’s Adam Smith (1723–90) believed that this market functioned like an ‘invisible hand’ ensuring that the world’s resources would be fairly distributed to those who needed them. The ‘neoliberalism’ of the latter part of 20th century was like liberalism on steroids or thatcher’s children liberalism without any moral reflection or concern.

In her book, This is Not Art: Activism & Other ‘Not-Art’, artist and writer Alana Jelinek also complains about the overuse of the term neoliberalism in the artworld without proper explanation and then, thankfully, offers a useful definition. She breaks the amorphous concept of neoliberalism down into three key economic principles or policies – privatisation, deregulation and trade liberalisation – which began to be implemented across the world at the end of the ’70s and in the ’80s when Margaret Thatcher’s government came to power in the UK and Ronald Reagan’s in America.9 These three principles or policies came to be accepted as the norm for the next 30 years.

Privatisation

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, Clement Attlee’s Labour government won a landslide victory with a mandate to implement socialist policy – to ensure ‘the common ownership and control of those things we all need to live happily and well’.10 They decided to do this by nationalising the ‘means of production’ – all our key services and infrastructure which they felt should be owned and run for the common good of the British people and not for private profit. The National Health Service was founded in 1948, the same year our railways were nationalised (then named ‘British Railways’). Our energy sector – gas, electricity and coal – were all taken into public ownership. There was a massive programme of social house building. From the ’50s into the ’70s major industries were also made public assets: telecoms, iron, steel, even cars (British Leyland Motors was part nationalised) and aeroplanes (British Airways).

When privatisation was first proposed as a way of reinvigorating these industries in the late ’70s by increasing ‘competition’, it appeared to many as a new and exciting idea. Thatcher’s government marketed it as ‘popular capitalism’. The plan was to sell shares in all these companies and that everyday folk on the street would buy them, people like Sid who featured in the British Gas ‘share offer’ advert I remember seeing on the telly in 1986. In the ’80s and ’90s nearly everything was flogged: telecoms in 1984, gas in 1986, electricity in 1990, buses were deregulated in 1986, railways in 1993, water in England and Wales in 1989,11 and much of our social housing stock was sold to individuals through the new ‘right to buy’ scheme.

A Brief History of Privatisation by Ellie Harrison, installed at Watermans Arts Centre, Brentford in March 2011. This interactive installation uses a circle of six electric massage chairs to re-enact the history of UK public service policy since 1900. Each chair represents a key service or industry and switches on when the date display reaches the year it was taken into public ownership and switches off again at the year it was privatised. (Ben Wickerson)

It was a story I attempted to visualise in my 2011 exhibition A Brief History of Privatisation (pictured opposite). When in 2013, David Cameron’s coalition government – picking up where John Major had left off – privatised the Royal Mail (which had been in public ownership of sorts since it was set up by the Crown in 1516), it was only the National Health Service still hanging on by a thread. The problem with ‘popular capitalism’, indeed with capitalism in general, is that it creates and intensifies inequalities12 – the more money you have, the more shares you can buy, the more power you acquire and, therefore, the more votes you get at the table. If people like Sid did buy shares, then they probably only had a tiny number to start with and more than likely sold them on to make a quick buck. The majority of all these companies – providing the essential ‘things we all need to live happily and well’– are now owned by foreign investors.13 Of course they don’t care about the quality or cost of services in a country they don’t live in, for these absentee landlords it’s always only about maximising their financial return. Once manufacturing industries are no longer guided by the social good of a nation, operations are quickly moved overseas to exploit cheaper labour elsewhere. It’s not as if we don’t use steel anymore, we just import it rather than make it in Ravenscraig (the steelworks in North Lanarkshire closed in 1992, four years after the privatisation of British Steel in 1988). This is the process known as ‘deindustrialisation’ – outsourcing all the carbon-intensive work (and therefore carbon emissions and pollution) to other parts of the world.

Deregulation

Then there’s the principle of deregulation. While Thatcher’s government were busy overregulating some aspects of society, introducing that infamous ‘Section 28’ – ‘the first new homophobic law in a century’,14 they were deregulating in terms of the ‘flow of capital around the world’.15 In 1986, Margaret Thatcher and her Chancellor Nigel Lawson created a ‘big bang’ on London’s Stock Exchange, with sweeping changes to the way the financial sector was regulated, or not. They moved trading in stocks and shares from a face-to-face endeavour to something done from behind the computer screen. They abolished the fixed commission on trading, which meant that people could now make more and more money by sitting on their arses pressing buttons. They ended the separation between traders and financial advisors which led to less impartiality and more dodgy deals. A flurry of company mergers and takeovers helped pave the way to the many ‘too big to fail’ bailouts and financial crises we’ve had since. And finally, they opened the doors to international investors.16

These first two neoliberal policies alone – privatisation and deregulation – help explain why most of Britain’s utilities are now owned by foreign companies. For example, ‘Scottish Power’ is actually owned by the Spanish multinational Iberdrola and ‘ScotRail’ is run by Abellio, the commercial arm of Nederlandse Spoorwegen – the railway company owned by the Dutch state. In England, ‘Thames Water’ is now owned by a consortium of international investors from Canada, Abu Dhabi, Australia, China and more.17 All of them exploit and profit from our basic needs to heat our homes, travel to work and drink water. One of the most insidious aspects of privatisation and deregulation has been the continual marketisation of every aspect of our lives and the increasing amounts of money we all now need just to survive.

Trade liberalisation

The third key neoliberal policy is trade liberalisation. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and what right-wing commentators claimed as the triumph of liberal democracy across the world, global trade negotiations quickened pace. The World Trade Organisation was founded in 1995 (as a successor to the General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade) to help facilitate and encourage international trade, thereby ‘supporting economic development and promoting peaceful relations among nations’.18 In her book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, Naomi Klein shows how these trade negotiations unfolded in flagrant denial of the impact of man-made carbon emissions on global warming, which had also emerged into mainstream public discourse in the late ’80s.19 Even Margaret Thatcher herself devoted her entire address to the United Nations General Assembly in 1989 to ‘the threat to our global environment’ which, she said, was ‘the challenge faced by the world community’ that had ‘grown clearer than any other in both urgency and importance’.20

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had been founded in 1988 with the aim of reaching an international agreement on emissions reductions to limit the onset of global warming and preserve a climate on earth which could continue to support human life. It held its first annual international Conference of Parties in 1995 in Berlin (COP1), with the first legally binding treaty – the Kyoto Protocol – agreed at the summit in Kyoto, Japan two years later (COP3). Meanwhile, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) continued in its completely contrary mission of helping ‘trade flow as freely as possible’,21 by getting more and more countries around the world to join its club. Its ambition of signing up China was accomplished in 2001. The WTO now has 164 members and 23 observers representing a vast majority of countries in the world. But, as Naomi Klein writes, nowhere in any of these trade negotiations was the fundamental consideration:

How would the vastly increased distances that basic goods would now travel – by carbon-spewing container ships and jumbo jets, as well as diesel trucks – impact the carbon emissions that the climate negotiations were aiming to reduce? How would the aggressive protections for technology patents enshrined under the WTO impact the demands being made by developing nations in the climate negotiations for free transfers of green technologies to help them develop on a low-carbon path? And perhaps most critically, how would provisions that allowed private companies to sue national governments over laws that impinged on their profits dissuade governments from adopting tough antipollution regulations, for fear of getting sued?22

And so carbon emissions have been increasing unabated ever since – more than half of all emissions since the start of the Industrial Revolution in 1750 have been released in the 30 years since 1988 – the three decades in which, with the help of the IPCC, we were meant to be urgently reducing them.23 So, put simply, these three neoliberal policies – privatisation, deregulation and trade liberalisation – have facilitated globalisation: the rapid transitioning to a world economy, and the hugely increased movement of goods and people and the explosion in carbon emissions that has inevitably resulted.

The New Economics Foundation (NEF) is a think tank founded in 1986 to promote a different way of structuring our economy, which takes into account the hidden costs of globalisation by putting ‘people and the planet first’. They highlight the three key consequences of neoliberal policies as being:

• hugely increased social inequalities,

• catastrophic environmental destruction, and

• frequent financial instability and uncertainty

It is neoliberal policies which have created the triple social, environmental and economic crises that we now face. But the worst outcome of all has been the falling levels of human well-being. NEF show that ‘people’s well-being is largely based on how we interact with other people’,24 and that in our neoliberal era, it’s the quality of our relationships and the strength of our real social networks (not our online ones) that has suffered the most. NEF writes:

Social networks make change possible. Social networks are the very immune system of society. Yet for the past 30 years they have been unravelling, leaving atomised, alienated neighbourhoods where ordinary people feel that they are powerless to cope with childbirth, education or parenting without professional help.25

In his book A Brief History of Neoliberalism, David Harvey explains how we sleepwalked up until this crisis point: ‘it has been part of the genius of neoliberal theory to provide a benevolent mask full of wonderful sounding words like freedom, liberty, choice and rights, to hide the grim realities of the restoration or reconstitution of naked class power, locally as well as transnationally’ to a global economic elite.26 But neoliberalism is more than just class war. Just as Margaret Thatcher’s chilling pronouncement in 1981 suggests: ‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul’. As much as it may have been against our own interests and our well-being in the long-term, all of us, ‘Thatcher’s Children’, raised in the ’80s and ’90s, came to embody the survival of the fittest mentality on which the free-market thrives. The greatest irony of all is that it’s the same neoliberal ideologues, whose mantra is ‘choice’, who tell us ‘there is no alternative’ (TINA) – that we cannot fight the logic of their system or address the hidden costs of globalisation. That’s what I seek to challenge.27 As Alana Jelinek writes:

Economically, neoliberalism rests on privatisation, trade liberalisation and deregulation. Ideologically, the concept equates to distrust of the state as the provider of social goods such as health, education and the arts. Neoliberal ideology also places an emphasis on individuals rather than systems, imagining individuals as rational beings within rational systems where choices can be made. There tends to be a generalised distrust of authorities: authorities are equated to the state and regulation.28

By the early ’90s the ethos of the self-interested entrepreneur had begun to permeate most areas of society, including public services once considered as ‘communal labour’ for social good, such as health and education. My mum and dad felt this on the frontline at Uxbridge College. In June 1991, in my last summer before high school, I remember being roped in to make placards for a bicycle blockade at the college gates. Teaching staff were protesting against the new management’s plans to buy themselves company cars with the college budget, which they claimed would ‘boost prestige’.29 My mum’s placard read ‘cash for courses, not cars!’ and mine, the product of a 12-year-old mind, said ‘fairer chances, not Sierra chances!’ I thought that model of Ford made a nice rhyme – they actually had their eyes on the ‘executive’ Ford Scorpios and some BMWS.

These self-appointed execs wanted the old guard out – those like my mum and dad who had devoted their lives to the college and who actually believed in the power of education to transform young people’s lives. My dad, aged 57, was offered early retirement that same summer and so he took it. Instead he spent the ’90s as a househusband – volunteering with the Parent Teacher Association at our high school, Drayton Manor (making school magazines and running car boot sales to raise funds), cooking us dinners, preparing our packed lunches and working on the allotment in Pitshanger Park, which our family had taken on in the mid-’80s.

Meanwhile, my mum carried on at the college, battling against the new managers’ misuse of funding. In 1997, when they decided to ‘outsource’ their lecturing staff to the now defunct private agency Education Lecturing Services,30 my mum and two other passionate troublemakers were placed on a ‘blacklist’. They were not allowed to reapply for the posts they had held for more than two decades. She had no choice but to resign and to look for work elsewhere where her skills and experience might actually be appreciated. She ended up teaching English at Southall College and then in Richmond, which had not yet been so badly affected by the neoliberal bug. I was well looked after and well loved, but teenagers don’t appreciate these things do they? It’s only with hindsight that the huge amount of support I got became clear.

Social mobility isnae what they say

In October 2017, I was invited by an arts organisation called Create to read and respond to their Panic! research into inequality in the arts. It was the first time I’d properly considered how terms such as ‘class’ and ‘social mobility’ are defined and measured by sociologists. They always tend to do this in reference to your ‘employment status’ or occupation. ‘Class’ is often measured by the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC), which is similar to the table Darren McGarvey reproduces in Poverty Safari.31

The NS-SEC clusters occupations together into eight groups, from 1 (higher managerial and professional, which includes doctors, CEOS and lawyers) to VII (routine occupations such as bar staff, care workers and cleaners), while VIII is those who have never worked or who are long-term unemployed. The NS-SEC… gives a clear definition of class, which is based on employment.32

Because the NS-SEC classifies all jobs in the creative and cultural industries in classes I and II – due to their high levels of creativity and autonomy – it means that, by their reading, there is no such thing as a working class person in the arts. You can only ever be ‘working class origin’. Indeed, when I heard Darren McGarvey being broadcast on BBC Radio 3 as part of their Free Thinking Festival or reviewing the newspapers one Sunday morning in summer 2018 on the bastion of bourgeois values that is BBC Radio 4’s Broadcasting House, I had a feeling he might have crossed the line. But it’s clear class divides run deeper than the sociologists can quantify. In their 2019 book, The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to be Privileged, authors Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison illustrate the extent to which ‘fundamental inequalities in resources (economic, cultural and social)’ originate ‘from a person’s family background’.33 Inequalities are regional too, and over the last 40 years we have seen the increasing ‘spatial polarisation of the UK’,34 as wealth has been centralised in certain locations – an issue I’ll come back to shortly. But first, one final definition.

Darren McGarvey defines ‘social mobility’ as the ‘gentrification of class consciousness’.35 It is certainly a concept which has only come to the fore as inequalities have intensified. The sociologists working on the Panic! research define and measure ‘social mobility’ quite precisely as the difference between what you do for a living now (your ‘destination’), and what your parents did when you were 14 years old (your ‘origin’).36 In 2016, David Cameron’s Conservative government set up the Social Mobility Commission, as part of the controversial Welfare Reform & Work Act 2016, which also imposed widespread changes to welfare including introducing Universal Credit and the ‘benefits cap’ – policies which have been responsible for pushing many more people across the UK into poverty.37 It’s hardly as if we needed a whole new ‘commission’ to tell us how cutting social protection for the poorest in our society might affect their ability to get a ‘good job’.

The one thing the Social Mobility Commission has done is publish an index of all the local authorities in England showing the ‘differences between where children grow up’ and their chances of ‘doing well in adult life’. In 2017, Ealing was ranked number ten out of 324 council areas, and of the top 20 all are in London or the south-east.38 According to their Index, even if you’re born to working class parents in Ealing, then you’re in the tenth best position in England to move into a ‘middle class’ profession yourself (as measured by the NS-SEC). Perhaps this explains why the local comprehensive which I attended in the ’90s, Drayton Manor High School, has many ethnically diverse alumni who have been most ‘mobile’ – BBC Economics Editor Kamal Ahmed (born 1967), Turner Prize- and Oscar-winning artist Steve McQueen (born 1969) and Iranian-born comedian Shappi Khorsandi (born 1973). That’s the effect of having access to the metropolis, where the global ‘economic elite’ live and where so much power, wealth, skills, investment and opportunity has been centralised. For example, public spending on public transport in London is 20 per cent more per capita than in Glasgow and bus fares are only £1.50 (compared to £2.50 on First Glasgow). This means young people are actually able to travel to take advantage of opportunities all over the city. So it seems that, no matter what your background, being a Londoner does, quite simply, make you more privileged. Does that mean that anyone with southern accent should be treated with resentment and contempt? Something to ponder later perhaps…

Waste not, want not

When I was 14 years old, my mum was a ‘further education teaching professional’ (Class II) and my dad was retired and therefore ‘not classifiable’ in the NS-SEC.39 He was born in October 1933 and was 45 by the time I arrived. He grew up in Nuneaton, a town in Warwickshire now ranked 296th on that same Social Mobility Index.40 He was one of the ‘lucky ones’ who passed the eleven-plus and made it into the Grammar School, from where he was able to get a free university place after doing his compulsory National Service in the Royal Air Force. He was the first person in his family ever to go to university. After graduating, he started working as an accountant in London, but didn’t like the ethos of the corporate world and so decided to go into teaching instead, which is where he eventually met my mum. He made it to the giddy heights of Head of Department of Business & Professional Studies at Uxbridge College (Class II or perhaps even Class I), before escaping when the new neoliberal management team swept in with their plans to ‘restructure’.

I was always mortified having a dad who was a pensioner and who seemed so much older than everyone else’s. I remember the trauma of being taunted at school: ‘Is that your granddad?’ the kids would say. He’d had two hip replacement operations (due to arthritis) before I’d even left school. From an early age, this installed a heightened anxiety about mortality, which has haunted me ever since. But having an ‘old parent’ also opens your eyes to different experiences and ideas. At the start of the Second World War, when my dad was six, he was evacuated to a small village called Rochford, having to leave his parents behind to face the bombs being aimed at nearby Coventry. Both my parents grew up under rationing, with a ‘waste not, want not’, ‘make do and mend’ mentality, which I absorbed as a child. As I grew up and began to fuse this ethos – based on the careful conservation of resources rather than mindless consumption – with environmentalism, I adopted it wholeheartedly as a guiding principle for every decision I made.

The irony was that the more I began to incorporate the ‘waste not, want not’ ethos into all of my thinking and action, the more I began to notice the glaring contradictions in the way my parents behaved. As much as my dad professed to be a ‘socialist’, proudly recalling that he’d voted Labour in every single election (bar one) since 1955, he didn’t seem to think twice about buying a holiday home, investing in stocks and shares and indulging his shop-a-holism by supporting many exploitative multinationals (such as Primark, Matalan, Wilko, Tesco and more recently online at Amazon) filling both houses with unnecessary crap. Perhaps this behaviour is just the sort of backlash to expect from any prolonged period of state-imposed restriction. But it was the ‘cognitive dissonance’ that always wound me up: saying one thing and doing the other. Talking the talk, but not walking the walk. But I also wonder whether it’s the difference between an ‘upwardly mobile’ person, like my dad, and a ‘downwardly mobile’ person, like my mum. It’s easier to reject something that you have tasted, thought about and decided you don’t like (as Gertie and Gus the bears did) than to reject something which our entire culture says you should aspire to because that’s what proves you have been a ‘success’.

Major setback

In 1992, there was a General Election. Most people (especially the man himself) thought Neil Kinnock was going to win it for Labour and put an end to 13 years of Tory rule (that had been almost my entire life). We stayed up watching Spitting Image before the results came in. I remember guffaws of laughter ringing around the living room. By the morning my mum was not so amused; struck with depression and disbelief that somehow John Major had managed to win. She cut a cartoon by Steve Bell out of The Guardian and put it in a clip frame on her bedroom wall. It depicted a precarious looking ‘Tower of Babel’ crushing the mass of people at the bottom. There were a few elite men in suits grasping huge bags of money perched at the top. Around the sides were wrapped the words:

We rule you,

We fool you,

We thicken you,

We sicken you,

We tax you,

We sacks you,

We are outrageous,

But you vote for us.41

By the mid-’90s, I’d got in with a ‘gang’ at my high school, Drayton Manor. It was mainly kids from middle class backgrounds who’d gravitated together, but the naughty ones into drinking, smoking and generally disobeying our parents. I remember the first time we were allowed ‘into London’ alone, when we were 13 or 14. We bought child Travelcards, caught the Central Line and hung about in Covent Garden, making a nuisance of ourselves by attempting to busk. That was an exciting place. On one of these trips ‘into town’, we heard about a big demonstration which was about to happen. ‘Kill the Bill: The Tories are the Real Criminals’ it said on the flyer. I didn’t really know what a ‘Bill’ was at that time, but it seemed important and looked like it was going to be fun. It was 9 October 1994, the third in a series of demonstrations that year against the Tories’ Criminal Justice & Public Order Act (which had been the Criminal Justice Bill in its provisional parliamentary form, hence the ‘Bill’). This legislation threatened to make ‘non-violent protest a criminal offence’,42 and to clamp down on rave culture by banning, specifically, the use of music in public places that had ‘a succession of repetitive beats’.43

The demo itself was like a party, loads of ‘repetitive beats’ and dancing. There were hundreds of police around, wearing hardcore riot gear. As we made our way towards Hyde Park, things started to get rowdier and there were a few scuffles. I remember a sharp intake of breath and this burning on the back of my throat which made us all gasp for air. Someone shouted ‘gas!’ and we covered our mouths with our sleeves and fled towards the park gates until we could breathe safely again. Inside, it felt like a battle scene. A huge line of police horses facing a crowd of protesters, including me and my three school friends. The protesters advanced, so did the horses. Several times they charged. I remember things being thrown and the terrifying thud of horses’ hooves galloping towards us as we ran for our lives.44 We returned home safely about 9pm. My mum was there, as she always was, waiting anxiously for our arrival: ‘Where have you been pet?’ ‘I’ve been in a riot!’

I gave my mum and dad far too many sleepless nights in my teenage years, which I now feel awful for. Drinking was what we did. Every weekend without fail, we would hit the vodka, the cider, the Tennent’s Super, down in the local park before we got our fake IDS sorted and could get into some of Ealing’s many pubs. We gradually made our way up from one, to two, to four cans of Strongbow Super, at which point I would generally start vomiting. Nearly all our friendships were based on how we related to each other in a drunken state – that was certainly the case with my first boyfriend who I barely ever saw when I was sober. We were always too drunk to bother with ‘safe sex’, no matter how many AIDS adverts we may have sat through on the telly.

When I passed my driving test at 17, I just carried on. Sometimes I ‘borrowed’ my mum’s car when she wasn’t there, sometimes I asked permission. One night in November 1996, I took it to drive my friends home after a few too many cans of cider at the local fireworks display. Three of us set off towards Hanwell. ‘You’re Gorgeous’ by Baby Bird was playing on the radio and we were singing along in unison. I was going too fast, I couldn’t judge the bend in the road properly in my inebriated state. ‘Look out Ellie!’ my friend Caro said. It was too late. The little Ford Fiesta wrapped itself around a lamppost and we all hurtled forward. Two of us had our seatbelts on, but Caro hit the windscreen. Then the noise started. A hideous roar coming from the engine. It was loud and unrelenting. Caro had blood on her face but she was still conscious. We all jumped out thinking the car was going to blow up like it always does in the films. It didn’t. But ‘Shit! What do we do?’ After some panicked deliberations, we went to the nearest payphone and I sheepishly called my mum. By the time my parents arrived, the police were there and so was the ambulance. Caro was taken to Ealing Hospital to be treated for concussion, and my parents had to watch while I was bundled in the back of a ‘meat wagon’ and driven to Ealing Police Station.

That was the first and only time I was grounded, which I was almost actually grateful for. I certainly knew I deserved it. My behaviour was totally out of control and it was a miracle no one had been seriously hurt. Shortly afterwards I caught glandular fever, so I had to stay at home for two weeks anyway. Spice Girls’ ‘Say You’ll Be There’ was playing on loop on The Box cable channel on the telly and I had lots of time to reflect. The next summer I was meant to be taking my A-Level exams: Art & Design, Mathematics and Physics. I had dreams of being an astrophysicist, perhaps even going into space. It was my mum that suggested I go to art college instead. Apparently, there was this thing called a ‘Foundation Course’, which I could do at a local college in Hounslow and stay at home for another year. Maybe that would give me a chance to channel my energy in more positive directions and to finally grow up.