13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

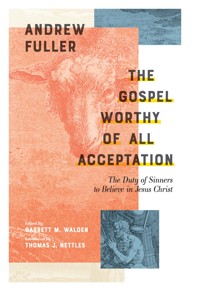

By the latter half of the eighteenth century, hyper-Calvinism had frozen parts of the Baptist denomination in England. Do the unregenerate have a duty to believe in Christ unto salvation? Do Christians have an obligation to offer the gospel to sinners? Fuller believed so, and in this significant book, he demonstrates his positive answers to these questions through careful biblical and theological reflection. Historically, the book was effective as a catalyst for missions and evangelism among evangelicals of all stripes. Hanover Press is pleased to offer contemporary readers an attractive new edition of this classic treatise, with a new introduction, informative footnotes, and a Scripture index.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

This republication of the 1805 American edition of Fuller’s seminal work on the interplay of the human and divine in faith, repentance, and salvation is a welcome and timely addition to the growing interest in Fuller’s works and his position as one of the most important Baptist writers and thinkers of the late eighteenth century. Fuller’s text is presented with precision and clarity, supported by Nettles’s concise and informative introduction and Walden’s pertinent biographical, historical, and bibliographical notes, all of which will be appreciated by both academic and general audiences.

–Dr. Timothy Whelan, Centre for Baptist Studies,

Regent’s Park College, Oxford

I am personally very encouraged to see the appearance of this fresh edition of one of Andrew Fuller’s key works, his decisive rebuttal of High Calvinism, otherwise known as hyper-Calvinism. Fuller himself called it “false Calvinism,” since it took critical matters relating to our salvation as sinners and pushed them to logical, but unbiblical, ends. In doing so, it set up a system of thought that had deleterious effects upon Fuller’s Particular Baptist community. Fuller’s decision to step into the controversy about whether or not God requires sinners to believe on the Lord Jesus Christ opened him up to numerous attacks, some of them quite personal. But he rightly judged that this was a hill to die on. And his elaboration of the way that saving faith is both a gift and an obligation—a perspective that came to be termed “Fullerism”—was central to the revival that came to Baptist ranks at the close of the eighteenth century and also foundational to the globalization of the gospel through men like Fuller’s dear friend William Carey. This is a classic work that bears both re-printing (a big thanks here to Garrett Walden and Hanover Press) and re-reading again and again.

–Michael A. G. Haykin, Professor of Church History,

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation

The Duty of Sinners to Believe in Jesus Christ

Andrew Fuller

Edited by Garrett M. Walden

Introduced by Thomas J. Nettles

Published by Hanover Press

a division of the London Lyceum Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

©The London Lyceum 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The London Lyceum, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization.

Hanover Press publishes material that confesses the Nicene and Apostles’ Creed and is consistent with the orthodox Protestant confessional tradition.

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the Authorized Version (KJV)

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.thelondonlyceum.com; www.hanoverpress.org

Paperback ISBN: 979-8-9881179-2-6

Editorial: Jordan L. Steffaniak and Garrett M. Walden

Cover Design: Julian Davis

Typesetting: Jordan L. Steffaniak

Indexing: Jeff Rathbun

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023919690

To Michael Haykin,

the mentor to a generation of Baptist historians

HANOVER PRESS BAPTIST THEOLOGY EDITORIAL BOARD

Jesse Owens, Senior Editor (Welch College)

Matt Shrader, Central Baptist Theological Seminary

Eric Smith, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Brandon Jones, Kairos University

Obbie Tyler Todd, Third Baptist Church

Zach Williams, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Colton Strother, Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

Joe Garner, Hannibal-LaGrange University

Bradley Sinclair, Emmanuel Baptist Church

Jake Stone, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

Aaron Pendergrass, Gateway Seminary

On Re-Printing Classic Baptist Literature

Part of the core mission of Hanover Press is to publish classic Baptist literature with the quality of a university press and the ecclesial focus of an evangelical publisher. To that end we seek to steward our great theological heritage by re-printing important works from our past with eyes for the Protestant church of today and tomorrow.

As such, all volumes in our Classics of Baptist Theology series include the following:

New introductions: Extensive new introductions to both the original author, the original context, and the nuances of the original text.

Lightly edited language and formatting: Archaic punctuation, words, and Scripture citations are updated for the modern reader. However, the vast majority of the text is left unchanged.

Updated bibliographic information: Footnotes are added with full bibliographic information on sources referenced in the original text.

Context: Additional historical, biographical, and theological information is footnoted with relevant details for the reader.

Updated indices: Scripture indexes and other appendices are added for research purposes.

We are committed to making historic Baptist literature available, accessible, and affordable to the church, with the quality that benefits future generations.

Jordan L. Steffaniak and Garrett M. Walden

Contents

Introduction

Andrew Fuller and His Celebration of the Worthiness of the Gospel

Early Life to Conversion

Path to the Pastorate

The Puzzle of Hyper-Calvinism

Summary of the Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation

Fuller’s Death

Editor’s Note

Advertisement to the Second Edition

Preface to the First Edition

Part I

The Nature of Faith

John Anderson's Contribution

Fuller's Response to Anderson

Fuller's Biblical Arguments

Responses to Objections

Part II

Unconverted sinners are commanded, exhorted, and invited to believe in Christ for salvation

Every man is bound cordially to receive and approve whatever God reveals

Though the gospel, strictly speaking, is not a law, but a message of pure grace; yet it virtually requires obedience, and such an obedience as includes saving faith

The want of faith in Christ is ascribed in the Scriptures to men’s depravity, and is itself represented as a heinous sin

God has threatened and inflicted the most awful punishments on sinners, for their not believing in the Lord Jesus Christ

Other spiritual exercises which sustain an inseparable connection with faith in Christ are represented as the duty of men in general

Part III

On the principle of holiness possessed by man in innocence

Concerning the Decrees of God

On Particular Redemption

On sinners being under the covenant of works

On the inability of sinners to believe in Christ and do things spiritually good

Of the work of the Holy Spirit

On the necessity of a divine principle in order to believe

Concluding Reflections

Appendix

Objections

Fuller’s Own Views

The consequences of the principle I oppose

Introduction

Thomas J. Nettles

Andrew Fuller and His Celebration of the Worthiness of the Gospel

Andrew Fuller (1754–1815) served his generation, and Baptists and evangelicals of the future, through his biblical, godly, and doctrinally faithful ministry. His churches thrived under his ministry. His cohort of Baptists maintained and clarified their doctrinal soundness. World missions took a giant leap forward. The work of the pastor-theologian was embraced as vital to the health of individual churches and the larger Christian community. Fuller played a major role in all of this.

Among the important points of his pastoral stewardship to his generation we find these: (1) His personal theological engagement with antinomianism resulted in a clear statement on the evangelical use of the law and the use of the law in sanctification. (2) His analysis of hyper-Calvinism and successful refutation of its leading ideas helped Baptists avoid becoming an irrelevant and solipsistic denomination. (3) His part in the founding and the sustenance of the Particular Baptist Missionary Society helped generate a world-wide engagement of evangelicalism in the ministry of world missions. When the opponents of the missionary labors of Dissenters sought to have Parliament rule against this society, Fuller wrote An Apology for the Late Christian Missions to India (1808). In addition to a pointed and sometimes scathing critique of these antagonists, Fuller defended personal character of the Calvinistic Baptist missionaries, as well as the honesty and integrity of their reports. Throughout, it was a masterful plea for the Christian world to embrace the cause of missions

and celebrate the fact that the gospel was being preached and biblical means were being employed for the conversion of the heathen. They went, not for temporal advantage or pecuniary gain, but because the Lord’s commission to “Go—teach all nations” remains relevant. Thus, they sensed the urgency of “imparting the word of life to our fellow subjects in Hindostan.”1

Spreading his talents and convictions broadly, Fuller’s apologetic and polemical works addressed the aggressive attacks on Christian orthodoxy by the Deists and Socinians. Concerning the latter, John Newton wrote to John Ryland Jr., “It is the best way of answering Dr. Priestley.… I hope Mr. Fuller’s book will do more to settle the unstable than anything that has been done yet. I think whoever has the least spiritual perception will see on which side the truth lies.”2

His efforts to inspire a purer evangelicalism not only tackled hyper-Calvinism but extended to polemical works concerning Sandemanianism and Arminianism. Robert Sandeman (1718–1771) summarized his understanding of the faith attached to justification as the “bare belief of the bare truth.” He argued that “Everyone who obtains a just notion of the person and work of Christ, or whose notion corresponds to what is testified of him, is justified, and find peace with God simply by that notion.”3For Sandeman, the sinner cannot love God until he is convinced that God has justified him “ungodly as I stand.”4Fuller exposed the error of this view as antiscriptural in its radical separation of repentance from faith. It was a style of easy believism.

Fuller’s extended engagement with Arminianism came in his response to the objections that Dan Taylor (1738–1816) raised to Fuller’s Gospel Worthy.Taylor, the leader of the reform among the General Baptists and the founder of the New Connection of General Baptists, wrote under the pseudonym of Philanthropos. Fuller’s Reply to the Observations of Philanthropos(1786) affirmed the leading points of Calvinist soteriology and gave a closely reasoned critique of Taylor’s Arminianism.5

1. Andrew Fuller, An Apology for Christian Missionsin The Complete Works of the Rev. Andrew Fuller, 3 vols. (1845 ed.; repr. Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1988), 2:829.

2. John Newton, Wise Counsel: John Newton’s Letters to John Ryland Jr., ed. Grant Gordon (Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 2 009), 293–294. For Fuller’s work on Socinianism, see The Calvinistic and Socinian Systems Examined and Compared as to their Moral Tendency in Complete Works, 2:108–242. For his refutation of Deism, see The Gospel Its Own Witnessin Complete Works, 2:3–107.

3. Fuller, Strictures on Sandemanianism, in Twelve Letters to a Friendin Complete Works, 2:566–567.

4. Fuller, Strictures on Sandemanianism, 2:567.

5. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:459–511.

Given the rigor and the importance of these engagements, it is no wonder that John Ryland Jr. could make this observation concerning the impression that Fuller left on his contemporaries:

Some of his friends, I am aware, have suspected, that the experience of progressive years had not greatly altered his propensity to think less of a man, for not entering into the minuter parts of his system. He certainly had taken a long while to settle his own judgment, on some points of very considerable importance: he should, therefore, not have forgotten, if he now walked in the midst of the paths of judgment, that a man who had wandered a little on the left side of the narrow way, might be as long in getting exactly into the proper track, as he himself had been in finding his way out of a thicket on the right hand.6

In the midst of these energy- and time-consuming works, Fuller did not falter in serving as an example of a spiritually and doctrinally aware pastor who guarded his own heart.

Early Life to Conversion

Andrew Fuller was born February 6, 1754, at Wicken in Cambridgeshire. His father, Robert, was a farmer who often moved to rent farms. He died in 1758 at fifty-eight years of age. His mother, Phillippa, outlived her son. Fuller practiced “husbandry” until he was twenty and entered the ministry.

He remembered the “sins of childhood” such as lying, cursing, and swearing. The last, swearing, he entirely left off when he was about ten years of age, “except that I sometimes dealt in a sort of minced oaths and imprecations when my passions were inflamed.” Lying he also “left off, except in cases where I was under some pressing temptation.” At age fourteen he began to have “much serious thought about futurity.” He noted that “the preaching upon which I attended was not adapted to awaken my conscience, as the minister had seldom any thing to say except to believers, and what believing was I neither knew nor was I greatly concerned to know.”7

Frequently curious about faith, Fuller devised for himself a test to see if he had faith. On an errand for his father, he captured two young hawks and tied them to a bush. When he returned, they had escaped. Recalling

6. John Ryland Jr., The Work of Faith, the Labour of Love, and the Patience of Hope, Illustrated; Inthe Life and Death of the Reverend Andrew Fuller(London: Button and Son, 1816), ix. Hereafter, this work is abbreviated as “Life of Fuller.” The general discussion of Fuller’s life will have this as its source, though page locations will be only occasionally mentioned.

7. Ryland, Life of Fuller, Letter I, 17–18.

“If you say to this mountain etc.” he commanded the two young hawks to appear. They did not. He was more troubled at the loss of the hawks than the supposed lack of faith. On another occasion, in climbing a tree to capture a rook, he perched on a bough very likely to break. He prayed and the bough did not break. Concluding that his prayer was answered, he descended from the tree with a heart full of pharisaical pride, supposing that he was one of the favorites of heaven.

Among some books Fuller read were John Bunyan’s (1628–1688) Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinnersand The Pilgrim’s Progress. He also read with eventual spiritual profit Ralph Erskine’s (1685–1752) Gospel Sonnets. At times he felt a spirit of benevolence for those he considered good people, especially those who were sociable with young persons. He used to wish that he had thousands of pounds to distribute to those of them “who were poor as to their worldly circumstances.” At times the young Fuller was the subject of “such feelings and affections, that I really thought myself converted.” He had a season of deep conviction in which he believed iniquity would be his ruin. The text of Romans 6:14 came powerfully into his mind, “Sin shall not have dominion over you, for ye are not under law, but under grace.” This phenomenon, particularly among antinomians and hyper-Calvinists, was generally considered as a promise coming immediately from God. He wept tears of joy, but soon, as he said, “I returned to my former vices with as eager a gust as ever.”

He had a subsequent experience of supposed restoration about six months later, again accompanied by a suggestive Scripture, this time Isaiah 44:22, “I have blotted out as a thick cloud thy transgressions, and as a cloud thy sins.” At fifteen, Fuller wrote, “notwithstanding my convictions and hopes, the bias of my heart was not changed.” Near the end of his life, Fuller remarked, “Amidst all my youthful follies and sins, I bless God that I was always kept from any unbecoming freedom with the other sex, or attempting to engage the affections of any female, except with a view to marriage.”8

In November 1769, he came under genuine conviction that issued in conversion. “In reflecting upon my broken vows, I saw that there was no truth in me. I saw that God would be perfectly just in sending me to hell, and that to hell I must go unless I were saved of mere grace, and as it were in spite of myself.”9He thought of giving up his quest for salvation but revolted at the thought and remembered a verse from Erskine:

8. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 36.

9. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 27.

But say, if all the gustsAnd grains of love be spent,Say farewell to Christ, and welcome lusts—Stop, stop; I melt, I faint.10

He was like a drowning man looking every way for help. He thought of Job 13:15, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him.” Again:

Yet it was not altogether from a dread of wrath that I fled to this refuge; for I well remember that I felt something attracting in the Saviour. I must—I will—yes, I will trust my soul—my sinful lost soul in his hands. If I perish, I perish.11

In the context of this testimony Fuller made several statements that were peculiarly related to his views having been formed in a hyper-Calvinist context:

“I was not then aware that anypoor sinner had a warrant to believe in Christ for the salvation of his soul but supposed there must be some kind of qualifications to entitle him to do it.”12

“I now found rest for my troubled soul; and I reckon that I should have found it sooner, if I had not entertained the notion of my having no warrant to come to Christ without some previous qualification.”

“If at that time I had known that any poor sinner might warrantably have trusted in him for salvation, I conceive I should have done so, and have found rest to my soul sooner than I did.”13

These statements should be seen in the context of another observation he made about some of his earlier convictions:

’Til now, I did not know but that I could repent at any time; but now I perceived that my heart was wicked, and that it was not in me to turn to God, or to break off my sins by righteousness. I saw that if God would forgive me all the past, and offer me that kingdom of heaven, on condition of giving up my wicked pursuits, I should not accept it. This conviction was accompanied with great depression of heart.14

10. Ralph Erskine, The Believer Wading through Depths of Desertion and Corruptionin The Sermons and Other Practical Works of the Late Reverend Ralph Erskine, A.M., vol. 7 (London: William Tegg, 1865), 246.

11. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 29.

12. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 29.

13. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 30.

14. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 21.

Path to the Pastorate

In April 1770, at sixteen years of age, Fuller was baptized and joined the church at Soham. Fuller remarked about an edifying relationship with a man who had been baptized with him, the forty-year-old Joseph Driver:

He … had lived many years in a very recluse way, giving himself much to reading and reflection. He had a great delight in searching after truth, which rendered his conversation peculiarly interesting to me; nor was he less devoted to universal godliness. I account this connection one of the greatest blessings of my life.15

In the autumn of 1770, Fuller confronted a church member who had been drunk. This led to the man’s remonstration with Fuller over his youth and his lack of knowledge of the deceitfulness of his own heart and that he did not realize that he “was not his own keeper.” Fuller’s action resulted both in the exclusion of the man from membership and a controversy concerning the power of men to obey God and keep themselves from sin. Fuller became very exercised about this wondering what all was meant by Philippians 2:13, “It is God who works in us both to will and to do according to his good pleasure.”

The controversy fragmented the relation between their pastor, John Eve (d. 1782), and the church so that he left the congregation in October 1771. Eve also felt disappointed in Fuller, for he had hopes for his usefulness in Christian ministry. Though this was a bitter and regrettable experience for Fuller, he eventually perceived that this conflict was the means of “leading my mind into those views of divine truth which have since appeared in the principal part of my writings.” Soon he read a passage in John Gill (1697–1771) that distinguished between the “power of the hand” and the “power of the heart.”16This was consistent with the very important distinction between natural ability and inability on the one hand and moral ability and inability on the other. Later, reading Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), the theological importance of this distinction was sealed.

After Eve left the congregation, Fuller’s mother arranged for him to train for a trade in London, stating as one of her reasons, “We had now lost the gospel, and perhaps shall never have it again.” She believed that in London he could hear “the gospel in its purity.”17Fuller’s heart revolted against the idea of relocating, not for any aspirations for the ministry

15. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 37.

16. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 42–43.

17. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 46.

but in order to remain with the small group that was seeking to maintain worship among them.

Due to the influence of Joseph Driver, Fuller was given several opportunities to preach before the congregation. Alternating between encouragement and despondency in these attempts, Fuller preached on Luke 19:10, “The Son of Man came to seek and save that which is lost.” Fuller remarked, “On this occasion I not only felt greater freedom than I had ever found before, but the attention of the people was fixed.” He traced several eventual conversions to the spiritual impact of that message.

In January 1774, an elderly lady, a member of the church, died, and left a request that “If the church did not think it disorderly, I [Fuller] might be allowed to preach a funeral sermon on the occasion.” The members agreed, set aside the twenty-sixth of that month for fasting and prayer, and called him to the ministry.

From that time, he preached regularly at Soham. In July, he was requested to take the pastoral care of the church. He consented in February 1775 and was ordained in the summer of 1775. He began with the theme often reiterated to his soul, “In all thy ways acknowledge him and he will direct thy paths.” (Proverbs 3:6)

His early mentors through books were John Gill, John Brine (1703–1765), and John Bunyan. He recognized that they all held to the doctrines of grace, but there was a difference in the manner in which sinners were addressed both in their writing and their printed sermons. Fuller noted, “I had not yet learned that the same things which are required by the precepts of the Law are bestowed by the grace of the gospel.”18He summarized:

With respect to the system of doctrine which I had been used to hear from my youth, it was in the High Calvinistic, or rather Hyper Calvinistic strain, admitting nothing spiritually good to be the duty of the unregenerate, and nothing to be addressed to them in a way of exhortation, excepting what related to external obedience.

Because of that, Fuller admitted that he did not “for some years address an invitation to the unconverted to come to Jesus.”19

The Puzzle of Hyper-Calvinism

Fuller’s early confrontation with theological issues prepared him for his polemical contributions. Fuller confronted the idea of the pre-existence

18. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 59.

19. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 51.

of the human soul of Christ, concluding that the human soul came into existence at the point of the conception by the Spirit in the womb of Mary. He had to think through the title “Son of God” in relation to the incarnation and the eternal relation to the Father and concluded that this title referred to the eternal sonship of Christ. Later, John Johnson (1706–1791) of Liverpool taught that God could not decree to permit evil without being the author of it, and that he would have glorified his elect even if sin had never intervened. Issues of divine sovereignty and human responsibility, with all their implications for the decretal purpose of God, emerged as vitally important biblical ideas. God had permitted evil and it could not be wrong to decree to do that which he actually did. These doctrinal challenges had formative implications for the issue of hyper-Calvinism. Fuller began to deal with this in a self-conscious way in the form of what Abraham Taylor (fl. 1727–1740) called The Modern Question:“Does God require us to do that which we have no power to do?”

This question had a multiplicity of implications that must be addressed in any thorough answer to it. We start with the question, “Does God require the unregenerate to repent of sin and believe in Christ?” which naturally requires its corollary, “Does God require gospel ministers to call on the unregenerate to repent of sin and believe in Christ?”

These two questions necessarily involve the issue of the character of the moral law. Does the revelation of the moral law imply its eternal relevance, or does the moral law of God represent only a temporary arrangement? Is it a revelation of God’s intrinsic holiness and the necessary relations of his exclusive prerogatives in the context of a temporal order, an order necessarily created by him? If the moral law implies the necessary relation of the creature to an immutably holy Creator does that involve universal duty for all rational beings, both human and angelic? Can that which is a duty to an eternal being ever be intermitted?

Then, “Does the duty implied in the law also imply a human ability to perform its requirements?” And, “How does this relate to gospel preaching?” The Arminian answers this way: Yes. Duty always implies ability. If there is no ability, there can be no punishment in not obeying a command. Since there clearly is a duty, each sinner also possesses the ability to repent and believe. The call to believe and the invitation to do so must always accompany proclamation of the gospel.20

The hyper-Calvinist agrees with the Arminian partially and constructs his answer this way: Duty certainly implies ability. But then he moves in the opposite direction and reasons that, since the sinner cannot repent

20. See Fuller’s discussion of this in Fuller, Complete Works, 2:381.

and believe, it must not be stated that it is his duty to do so. The reason that the hyper-Calvinist denies the duty to repent evangelically and believe the gospel is that such a requirement was not present in his original condition of innocence. Fallen man is guilty and, though he cannot obey presently, should obey the law of God, since it was written on the heart in the condition of innocence. The simple positive command he received was the test of his willingness to obey the law written on the heart. There was no indication, however, that man could be rightly related to God through a mediator provided by the mercy and grace of God. Since mercy and grace come apart from any work of the law or any merit on the part of the sinner but is bestowed in a sovereign manner, it cannot be the duty of a person to perform what only can be done by grace and was not revealed in the beginning.

The key question was, “What is the relation of the law to the gospel?” Does the gospel imply, or necessarily involve, the fulfillment of the law in order to gain eternal life? The relation of law to gospel shows the importance of Fuller’s recognition later, “I had not yet learned that the same things which are required by the precepts of the law are bestowed by the grace of God.”21

In 1776, Fuller met John Sutcliff (1752–1814) and soon John Ryland Jr. (1753–1825). He wrote:

In them I found familiar and faithful brethren and who, partly by reflection, and partly by reading the writings of Edwards, Bellamy, Brainerd, &c. had begun to doubt of the system of False Calvinism to which they had been inclined when they first entered the ministry.

Robert Hall Sr. (1728–1791) of Arnsby recommended to Fuller “Edwards on the Will.” At this time, he began to record random ruminations concerning these issues. He began more formal composition in 1781 and later organized the developed product for publication in 1785 as The Gospel of Christ Worthy of All Acceptation: or The Obligations of Men Fully to Credit, and Cordially to Approve, Whatever God Makes Known, Wherein is Considered the Nature of Faith in Christ, and the Duty of Those where the Gospel comes in that Matter.

After years of struggle as to whether he should leave Soham and accept an invitation to go to Kettering to serve as pastor, he eventually moved to Kettering in October 1782. One year later, he finally was settled with a service of installation in which he shared something of the exercises of his mind during this process. Also, he set forth his confession of faith. Ryland

21. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 59.

commented about the struggle that Fuller had in reaching a final decision in this matter of the move from Soham to Kettering:

But as to Mr. Fuller’s removal every serious Christian must admire the conscientious manner in which he acted, the self-denying scrupulosity which kept him so long in suspense, the modest manner in which he asked counsel of his senior brethren, and the importunity with which he implored divine direction.… Men who fear not God would risk the welfare of a nation with fewer searchings of heart, than it cost him to determine whether he should leave a little Dissenting church, scarcely containing forty members besides himself and his wife.22

In 1781, as mentioned above, Fuller had begun writing out thoughts on the burning issue of the Modern Question. By 1785 this resulted in his publication of the first edition of The Gospel of Christ Worthy of All Acceptation,a title taken from 1 Timothy 1:15. Response to this work was so vigorous, varied, and widespread that it called for a second edition in 1801 with some significant changes (and a slightly revised and shortened title). Below is a summary of this second edition.

Summary of the Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation

In the preface, Fuller introduces several ideas upon which he expands in the main body. Unbelief: Is it doubting our own personal religion, or calling into question the revealed truth of God? He defined belief as a full persuasion of the truth of what God has said, giving introduction to another polemical work later produced on Sandemanian issues.23He discussed the distinction between natural ability and moral ability derived from Edwards’s Freedom of the Will(1754). He pointed out the agreement of Arminians and hyper-Calvinists on inability in relation to duty.

He also gave brief attention to seven doctrinal issues that this dispute is notabout. It is not about the doctrine of election or any of the discriminating doctrines of grace. It is not about who should be encouraged to consider themselves as in possession of the blessings of the gospel, for its blessings are not for unbelievers but only for believers. It is not about whether sinners are required to do more than the law requires, but about how much full love to God includes. It is not as to whether men are required to believe any more than is reported in the gospel, or anything that is not true, but “whether that which is reported ought not to be believed with

22. Ryland, Life of Fuller, 70–71.

23. His Strictures on Sandemanianism, in Twelve Letters to a Friend(1810).

all the heart, and whether this be not saving faith.” It is not about whether unconverted sinners are able to turn to God, and to embrace the gospel; but what kind of inability they lie under — the want of natural powers, or the want of a heart? It is not about whether faith is a virtue on the basis of which we are justified. It is not; only the righteousness of Christ constitutes our justification. It is not about whether unconverted sinners are the subjects of exhortations, but whether they may be exhorted to spiritual duties.

Next, in Part I, Fuller discusses the importance of the subject. It concerns the nature of saving faith according to the Bible, and thus, “Whether faith be required of all men who hear, or have opportunity to hear the word.” He treats it from a wealth of having heard much preaching from the hyper-Calvinist side and frequently comments on how they present these things in their sermons. For example, does faith include a persuasion of our interest in the saving work of Christ? Fuller objects to this notion of faith, contending rather that nothing can be an object of faith except what God has revealed in his Word. He has not revealed the status of any individual in particular, but only the spiritual traits of those who have true faith. Scripture presents faith as terminating on something outside of us, specifically, Christ and his perfect person and perfect work. Believing ourselves to be in a state of grace is a far inferior object, however comforting and desirable it may be, to the contemplation and increasing knowledge of the glory of Christ.

As an aspect of this discussion, Fuller rejected the positive side of the Marrow controversy, that an appropriation of faith is to believe that Christ is ours. Such a so-called faith calls upon a person to believe, or have faith in, what is not revealed but must be deduced upon certain conditions. The illumination of heart promised in Scripture is not a revelation that we in particular belong to Christ, but that the propositions of divine revelation are true and excellent, and any promises connected with them God faithfully will honor. The revealed propositions that constitute the gospel give warrant to every person who hears the gospel to believe and establishes their duty to do so.

In Part II, he gives a larger demonstration of arguments to prove that “Faith in Christ is the duty of all men who hear, or have opportunity to hear, the gospel.” Not only are all persons, both in the Old and New Testaments, invited, commanded, and exhorted to worship the Son, they are called on to see this duty as intrinsically worthy of their devotion and love, so that with all their judgment and their affection they embrace revealed truth. “A real belief of the doctrine of Christ is saving faith, and

includes such a cordial acquiescence in the way of salvation as has the promise of eternal life.”24

Fuller argues from the symmetry of God’s revelation for the duty of saving belief. The law is the image of God and must be loved; the gospel is the image of God and must be loved; Christ is the image of God and must be loved; angels praise God for all his works and praise him more exuberantly the more they see of the unfolding of all his plans. Though the gospel is a message of pure grace, its characteristics and effects call for perfect concord of mind and heart with its parts and effects. For example, “The goodness of God … though it is not a law or formal precept, yet virtually requires a return of gratitude.” So it is with reconciliation, an act implied in the atonement that requires a cessation of enmity and alienation to an infinitely holy and good being:

If sinners are not obliged to be reconciled to God, both as a lawgiver and a Saviour, and that with all their hearts, it is no sin to be unreconciled. All the enmity of their hearts to God, his law, his gospel, or his Son must be guiltless.25

Unbelief itself is a sin ascribed to man’s depravity. If the outflow of human depravity is no sin, then unbelief is no sin. But if the outflow of human depravity constitutes the source of every transgression, then unbelief is the sum total of transgression and must be seen as criminal and belief as infinitely obligatory. Again, Fuller discusses the distinction between natural inability and moral inability. The same carnal mind that is at enmity with the law of God is at enmity with the gospel. Unbelief is a sin of which the Holy Spirit convicts the world. It cannot, therefore, be anything less than obligatory and certainly is much more. God has threatened and inflicted the most awful punishments on sinners for their not believing on the Lord Jesus Christ. Fuller argues that when condemnation is mentioned in conjunction with specific sins, then those sins are, in fact, among the procuring causes of their damnation and not a mere “descriptive character” of the condemned. Other spiritual exercises, which sustain an inseparable connection with faith in Christ, are represented as the duty of men in general. Every exhortation to a good and holy thing is an exhortation to a “spiritual” thing; thus, men who are supposed to be good and holy may be exhorted to “spiritual” things such as love of wisdom, love of God, thankfulness to God, cordial approbation of the divine character, love to Christ, fear of God, repentance and godly sorrow for sin, humility and lowliness of mind.

24. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:349.

25. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:353.

Having dealt with this theological issue for some years and in the most anguishing workings of soul, Fuller was able to anticipate the most pertinent objections to his theological conclusions. He discussed compatibilism in relation to divine decrees and human responsibility. He discussed the holiness of man in the unfallen state as compared to the holiness gained in the state of grace and affirmed that the latter is a return to the former. Thus, it operates according to the same standard: conformity to the moral law and its driving requirement, supreme love to God. Concerning the decrees of God: the decrees do not diminish duty, nor stop the prophets or the apostles from warning of the consequences of pursuing a course of sin and rebellion, even when God’s intention to bring judgment has been specifically prophesied. He quoted John Brine approvingly, “God’s word and not his secret purpose is the rule of our conduct.”26

In his discussion of the redemptive work of Christ, Fuller alters his view from what was a “commercial” view to a view of the atonement’s universal sufficiency, but particularity in its application to the elect only. This is a view which he showed was consistent with the teachings of John Owen (1616–1683) and the Synod of Dort (1618–1619). Fuller recognized that sinners are still under a covenant of works. They are under its precepts as the immutable will of God, under its promises as what would accrue had it never been broken, and under its curse as the penalty for disobedience. They are not under it as a term of life by personal obedience for they already are corrupt and under the verdict of death. Its promise of eternal life, however, comes to them through the imputed righteousness of Christ, a status attained only by believing the gospel.

Fuller revisited the issue of the inability of sinners to believe in Christ and do what is spiritually good. Again, he included a detailed discussion of the relation between natural inability and moral inability and points out the convergence of “False Calvinism” with Arminianism in their agreement that where there is no grace there is no duty. This issue also informed Fuller’s treatment of the necessity of effectual calling. Some would argue that if one is fully dependent on the work of the Spirit, then belief cannot be of duty. Conversely, if belief is of duty, then it cannot be a gift of the Spirit. Instead, Fuller argued, “But if we need the influence of the Holy Spirit to enable us to do our duty,both these methods of reasoning fall to the ground.”27The necessity of a divine principle for a cordial belief does not eliminate the duty of belief but testifies to how deeply sinful we are in needing omnipotence to enable us to do what is the consummate duty of

26. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:373.

27. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:389.

the creature, the sinful creature. “To me,” Fuller affirmed, “it appears that the necessity of Divine influence, and even of a change of heart, prior to believing, is perfectly consistent with its being the immediate duty of the unregenerate.”28

In his “Concluding Reflections” before the appendix, Fuller expanded his discussion on faith as a duty. Though faith be a duty, the requirement of it is not to be considered as a mere exercise of authority, but of infinite goodness, binding us to pursue our best interest. Though believing in Christ is a compliance with a duty, yet it is not as a duty, or by way of reward for a virtuous act, that we are said to be justified by it. Instead, justification comes by union with Christ in his righteousness, and faith involves a frank admission of unworthiness and submission to the Worthy One.

How does such a view of the duty of all men to believe the gospel affect the gospel ministry in dealing with the unconverted? We must exhort sinners to nothing less than believing to the salvation of their souls. He pointed to the preaching of Christ and the apostles as examples of such urgent exhortation. These are not merely duties, but duties of the most urgent sort.

How should doctrine and exhortation be mixed? It is never wrong to introduce doctrine into a discussion for, presented truly, it leads to the virtues of love, honor, worship, and at the same time prompts sorrow for sin and yearning for Christ. “Such is the connection of the duties as well as the truths of religion, that if one be truly complied with, we need not fear that the others will be wanting. If God be sought, loved, or served, we may be sure that Jesus is embraced; and if Jesus be embraced, that sin is abhorred.”29The preaching of law and gospel, handled properly, does not promote self-righteousness but repentance and the hope for mercy.

Fuller closed with this summary of the relation between exhortation to holiness and exhortation to embrace Christ:

They were not afraid of exhorting either saints or sinners to holy exercises of heart, nor of connecting with them the promises of mercy. But, though they exhibited the promises of eternal life to any and every spiritual exercise, yet they never taught that it was on account of it; but of mere grace, through the redemption that is in Jesus Christ. The ground on which they took their stand was, Cursed is every one who continueth not in all things written in the book of the law to do them. From hence, they inferred the impossibility of a sinner being justified in any other way than for the sake of

28. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:381.

29. Fuller, Complete Works, 2:392.

him who was made a curse for us; and from hence, it clearly follows, that, whatever holiness any sinner may possess, before, in, or after believing, it is of no account whatever, as a ground of acceptance with God. If we inculcate this doctrine, we need not fear exhorting sinners to holy exercises of heart, nor holding up the promises of mercy to all who thus return to God by Jesus Christ.30

To the 1801 second edition, Fuller added an appendix on “Whether the existence of a Holy Disposition of Heart be necessary to believing.” His antagonist, a Scots Baptist named Archibald McLean (1733–1812), had given a public rebuttal to Fuller’s first edition, challenging Fuller’s argument for the necessity of regeneration prior to the possibility of exhibiting saving faith. McLean believed faith to be a duty, but believed that the contention of prior holiness in the will, or affections, destroyed to doctrine of justification by faith. His views were similar to Robert Sandeman’s (1718–1771). Fuller countered, “If no holy disposition of heart be presupposed or included in believing, it has nothing holy in it; and if it have nothing holy in it, it is absurd to plead for its being a duty.” Fuller was accused of denying the doctrine of justification by grace and subverting it through requiring works of the law. McLean based his argument on Romans 4:5, “To him that worketh not but believeth on him that justifieth the ungodly.” He understood by the term “he that worketh not” one that has done nothing yet that is pleasing to God; by ungodly, one that is actually an enemy to God. Though McLean believed faith was the foundation of succeeding virtue, he saw faith itself as merely an intellectual activity, the moral state of