Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

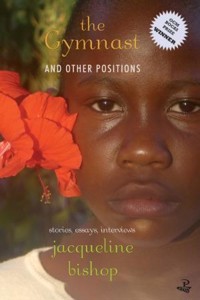

Winner of the 2016 OCM Bocas Prize for Non Fiction. Beginning with the promptings of the erotic title story, Jacqueline Bishop came to see the hybrid format of this book, with its mix of short stories, essays and interviews could begin to encompass her desire to see where she had arrived at in a creative career that encompassed being published as a novelist, poet, critic and exhibited as an artist. How did these sundry positions connect together? What aspects of both conscious intention and unconscious, interior motivations did they reveal? The stories, none more than a few pages long, can be read at several levels. The mentor who teaches the child gymnast a contortionist's erotic positions, the adoptive mother who shoots down ex-partner and adopted child when the former debauches the latter as the subject of pornographic photographs; the relationship between tattooist and the woman who offers her naked body for decoration are all sharply and persuasively realized as short fictions, but they also hint at a writer's interior dialogue and can be read as parables about the relationship between the free imagination and the controlling and even potentially betraying power of art. The essays explore more conscious areas of expression. They deal with the experiences of maternal separation, family histories and mythologies, the search for grounding in the life of a Jamaican grandmother, the relationship with a male writing mentor, travel to Morocco, the inspiration of the writing lives of Jamaicans Claude McKay and Roger Mais and how 9/11 showed her how deeply she had become a New Yorker. The interviews, which investigate sometimes her writing, sometimes her art, and occasionally both, provide context for the stories and the essays. They are at their most revealing when interviewers ask Jacqueline Bishop questions she hasn't asked herself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JACQUELINE BISHOP

THE GYMNAST & OTHER POSITIONS

STORIES, ESSAYS AND INTERVIEWS

CONTENTS

Introduction: Looking Forward by Looking Back

Part 1: Stories

The Gymnast

Tall Tale

Oleander

Terra Nova

A Giant Blue Swallowtail Butterfly

Soliloquy

Soldier

Zemi

Effigy

Flamboyant Tree

Part 2: Essays

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Walker Family Stories

Stories of a Birth

Photographs on the Mantelpiece

Sailing with Wayne Brown

Love Songs to Morocco

“Covering” Female Sexual Desires

Surviving Whole: An Introduction to Roger Mais’ Black Lightning

Claude McKay’s Songs of Morocco

A Clear Blue Day

Part 3: Interviews

The Bookends Interview

Charting a Literary Journey

A World of Superimposed Maps

Art: A Synaesthetic Experience

Writing Across The Diaspora

The Haunted Self

Interview with John Hoppenthaler

“Inside I Always Knew I was a Writer”

“Reliving, Rewriting, Re-imagining”

From Nonsuch to Bordeaux: An Inter-Island Conversation on the Work of John Dunkley

For Emma – my grandmother

We tell ourselves stories in order to live — Joan Didion

INTRODUCTION LOOKING FORWARD BY LOOKING BACK

She had started a reading series and she wanted me to read. Shortshort stories. A format I had never tried before. The theme for the reading, for there was a theme for all the readings she was to host, was “assume the position”. We both laughed at the naughtiness of it all, and, a day or two before the reading, I sat down and wrote the story. I considered myself then a writer of novels and fairly long short stories, but the minute I sat down “The Gymnast” popped right out, as if it had been waiting for me to just come along and unearth it. I wrote this short-short story in the way that I often write poetry, in a rush and in one fell swoop. Then the revising begins. After this first story, “The Gymnast”, I would go back again and again to writing shortshort stories and soon these short-short stories started to take on a life of their own. In this way the first third of this book came into being. As I looked back over these stories I was struck by their diversity of experiences, and I am pleased that they have an almost equal focus on the perspectives and preoccupations of men and women. I also liked the interiority of these stories, as if they were thoughts spoken to one’s self. Read together they seemed to form a cohesive whole.

Still, in looking at the stories as a group, and thinking about publication, I started to feel that there was something missing, something needed to add heft, and it is in this way that this strange hybrid of a book was born. For this book with its stories, its essays, and its interviews is a strange bird indeed. Yet, in so many ways I feel that this book, of the five books I have published so far, is the most representative of who I am, because it is a coming together of so many parts of myself. My good friend Earl McKenzie, who is a creative writer, visual artist and philosopher, among many other things, has written about himself that, “many years ago a friend of mine… had prophesied that one day my… writing and painting would come together in a single praxis. With my painting on the cover of my… book of poems, this, I felt, was the nearest I had come to the fulfilment of this prophecy.” Similarly, The Gymnast feels like the fulfilment of a personal philosophy. This book gives me a chance to reflect on the work that I have done so far and think about the work I hope to do in the future – gives a chance of looking forward by looking back. It gave me a metaphor for my creativity and my life, the collaging and quilting, the superimpositions, the piecing together of things to make somewhat of a whole. Asante Sana.

PART ONE

THE GYMNAST

Candlestick: A position where the gymnast is essentially on her shoulders with feet pointed towards the ceiling. The gymnast’s arms can either be behind her head or pushing palms down on the floor to help her support and balance herself.

Many people find it hard to believe that this was the first position he taught me. The first time, he said, he realised that I had real talent. Those long ago days of my childhood in Jamaica, the two of us behind the thick green hedge of the hibiscus, with its bright red flowers! I must have been ten that first time, and he kept insisting that he was only slightly older. ‘Bet you cannot do this,’ he dared, contorting himself into this weird shape. Of course I wanted to show him that I, too, could do it. Of course I had to show him that I, too, could balance on nothing but my bare shoulders. And, before long, there I was, looking at the world upside down, and him walking around, my trainer, as he would always be, his arms behind his back. ‘Not bad,’ he kept saying, nodding. ‘Not bad at all!’

Handstand: A proper handstand is extended towards the ceiling. The body is vertical, supported on the hands with arms straight and elbows locked.

This was the position we practised next, skipping right over the arch, the aerial and the bridge – positions he said I already knew to heart. All the nights I would steal out of my parents’ home to be with him! Those inky blue-black nights that he walked around me, again and again, inspecting what he saw. I must have been thirteen by then: hips rounding out, breasts becoming a handful. ‘Hold it, hold it,’ he kept saying. ‘Straighten out those skinny legs of yours. OK, now slightly open those thin brown legs of yours. You are not afraid, are you? You could not possibly be afraid of me. How long have I been your trainer? Teaching you, training your slim young body how to assume the various positions? Breathe. Let it out. That’s right. Now, you hold that position. All I am doing is looking. Nothing else. Just looking at what is flowering between your legs.’

Lunge: Start by standing with feet together. Take a large step forward. Bend your front leg. Both feet should be turned out somewhat. Arms should be extended upwards so that a straight line runs up from the rear foot parallel to the hands.

Naturally I could not wait to get close to him. I would now do anything to be with him. All of sixteen, or was it fifteen, years old. We would be going places, he promised. Far away places like New York and Toronto. Women in those places, he had heard, could do tremendous things with their bodies. A contortionist he had seen in a magazine, he said, stroking the stubble of hair that was not there, had arranged herself into so many positions all at once, a person looking at the picture, the spectacle, could never tell where a hand or a leg began. ‘To have a woman like that!’ he kept saying, smiling to himself. ‘A woman who could assume all those positions. A woman whose body and bones are that limber. To have a woman like that!’ That was the first time I ran away to be with him.

Straddle: In which the gymnast’s legs are spread wide.

I am eighteen now, so this is legal. This, I tell everyone, is what I have always wanted to do; what, in fact, I was born to do: straddle this man. Straddle my man, my first and only trainer. Now at last I can best that contortionist! Where was it that she was located again? New York. Yes, I think it was New York. Well, I am in New York now. Attending a university here. And I won’t tell you what I did to that big hairy man at the United States embassy in Kingston to make sure that my boyfriend also got a visa to come with me to the United States, as my trainer. How I closed my eyes and saw nothing but flowers, bright red hibiscus and red ginger flowers, and the pale blue sky, and, further, faster, myself swimming in the dark blue ocean. Yes, that day at the embassy I saw the look that came into that man’s eyes. I could feel the flush travelling through his gigantic, well-fed body as he looked at me. ‘You have such a perfect body,’ he kept saying. ‘A gymnast’s body. A contortionist’s body. The positions you must be able to assume with that body!’

Cartwheels:A basic exercise in which, limbs akimbo like the spokes of a wheel, the body rotates across the ground like a wheel, hands and legs following one another. (Children love this exercise.)

My mother was right. Cartwheels were what I was left doing, in the end. One after another, trying to get my trainer’s attention; trying to get anyone’s attention. Oh, I could do the hip-circle, the front split, the layout, the tuck, better than anyone else I knew. Oh, I had caused a sensation in my own right: the first Jamaican world-class gymnast.

But after a while that did not seem to matter to him, my trainer, the one I wanted it to matter to the most. So many women, so many contortionists resided in New York City! He, my trainer, got very busy. Became just like a writer. I have since dated a few of those, so I know the type well. Always something on their minds. Thinking up some new and daring position.

I don’t think he told me goodbye the day he left, my contortionist, my trainer. I don’t think there was even a note. I remember just coming home to an empty apartment. Then, for days, endless crying.

That was until the day when, for no particular reason, I got up and pulled my training rug out of the closet. Set it in the middle of the floor of my empty apartment. Unfolded my long, limber, dark brown arms and legs. Resting on my shoulders, with my arms behind my back, I thrust my legs up as if trying to reach the cream-coloured ceiling. My legs seemed longer, more slender and even browner than before. Such a lovely sheen! And my fingers, I thought delighted: how long and slender they, too, were! Long enough to put anywhere inside my body.

I wanted to sing, to hug myself and dance and sing. Mine, all mine, my long brown fingers! The bananas I could now see sitting on top of my empty refrigerator, the ones my grandmother had sent to me all the way from Jamaica. Their bright yellow, freckled brown, skin. My grandmother’s long, slender, near-perfect bananas that she grew in the country. What was it that my grandmother had been trying to tell me, the last time I had gone to visit her, my eyes brimming with tears? She had taken my hands into hers, stroked my long brown fingers. ‘So beautiful,’ she kept murmuring, seemingly to herself. ‘Long and slender, just like my bananas.’

‘Go on, take one,’ she had said, coming out of the house with some of her near-perfect fruit. ‘You are, your mother tells me, someone who likes to push her body, who likes to do things with her body, who likes to test the limits of her body. The positions I have heard,’ she said, smiling admiringly at me, ‘you can assume!’

‘Go on, take one,’ she said, with a mysterious, triumphant look in her eyes. ‘See for yourself what these bananas can do.’

TALL TALE

It took her a long while to figure out what the photographs were of, and a still longer time to figure out who was in the photographs, and, when it finally dawned on that part of her brain that edits and selects who the photographs were of and just who had left them there on the breakfast table for her to find first thing in the morning, she knew she would kill him.

Yes, she acknowledged, the bile rising in her mouth, the photographs were of her daughter. Her child. In some ways their child, for hadn’t Lloyd help her raise this child from knee-high to almost-a-woman? She shook her head. He had waited until her child, their child, Simone, had made it just past the age of consent to make his move. Yes, she would kill him. Of that she was sure. For here now was her child in poses that could be found only in those lurid magazines that she passed quickly wherever she saw them being sold. And there she was, her child with the almond-shaped eyes, smiling at someone – him, most likely, the man who had helped raise her; the man who had been like-a-father-to-her – smiling and sticking her fingers into various parts of her body. Effervescent flashes of pinks, purples, bruised red.

And that bedspread that their daughter was posing on, hadn’t they bought it together, all three of them, on Fordham Road one beautiful spring day several years ago in the Bronx? They had gone to the New York Botanical Garden to see a show called “Andalusian Paradise” and everyone who saw them had smiled at the beauty – the rightness – of the family. Mother, father, pumpkin-coloured, talking-too-much daughter between them. Lime green and bright yellows were the blossoms on the duvet covers they had brought that day. Her daughter, Simone, had picked out the sheet because she so loved the colours, especially after such a spectacular show at the botanical garden. When she reached for her purse to pay for the comforter, Lloyd had stayed her hand. He would pay for it. He would take care of things. From now on.

It was on that very same bedspread he had positioned the laughing child in these most grotesque of photos. Perhaps it was her mind protecting her again, but it took her a while to realise that there was also a letter with the pictures, a letter written in her daughter’s still childish hand. Even as she reached for the letter, she wondered why she should read anything the two of them had to say. But still she opened up the crisp white piece of paper, probably torn from her daughter’s notebook, and she read a little of what it had to say, stopping once in a while to steady the bile continually on the rise in her mouth. Something about the two of them being in love. They hoped she would understand. They had taken off together.

She put the letter down. She remembered the first time she saw Simone at the Maxfield Park Children’s home in Kingston. She had gone back to the island specifically to get a child, something she had always promised herself she would do. A way of giving something back, or, at the very least, helping someone from the land where she had been born and where she had grown up. Her homeland. Her motherland. The island of Jamaica. She was thirty-six years old then, had spent the better part of her life getting degrees and focusing on her career; now it was time to focus on someone other than herself. And there was the little pumpkin-coloured girl with the almond-shaped eyes, leaning against a wall, so shy and retiring. While all the other children smiled too-wide smiles to show strong white teeth, and had slender, pliant arms folded delicately on their laps, the little girl, Simone, had her back against the wall. She was told that for the many months she had been there, in the children’s home, Simone had barely spoken a word.

“No,” the administrator told her when she began looking closer and closer at the little girl her heart immediately told her was her own, “she is not up for adoption. Something not right with that child.” The word “troubled” was used several times over.

But wasn’t that what she had gone to school for? She with her psychiatric social worker eyes, wasn’t that what she had been trained to do? No, this child was not troubled, but vulnerable, needy, and who could resist the pull of those sad, dark eyes? Yes, they were communicating with her, those eyes, drawing her in. Pulling her in. Like a luscious chocolate-coloured mami wata, deep into the dark blue ocean. The child was pleading with her, begging her to choose her, take her back with her to America.

Simone was nine years old by the time the adoption and immigration papers were finalised. Then, before she knew it, the child was sitting on the forest green sofa in her living room in the Bronx. Looking around, ever so shyly. All the posters of Jamaica up on the walls. The dwarf banana plant she had struggled to grow in her living room. Its flat, silver-green leaves. The crudely made wooden sculptures. All the indications, she hoped, for this child, her child with the deep dark eyes, to know that after many tumultuous journeys, she was finally home.

She had read the file on this child: her mother a lady of the purple-blue nights working the wharves in downtown Kingston; the father, judging by the child’s orange-coloured, freckled face, some European sailor. And to think, the mother was supposed to have said, a smile lighting up her luminous dark face, that of all the seeds sown that would germinate and take root, it was those of some European sailor that found a fertile foothold in her body. The mother smiled again at that.

Still, that had not stopped the mother giving the child away. Someone should have told her about the responsibility. All the times she was shyly, proudly, touching her swollen body, someone should have told her about the crying at night. The endless changing of nappies. She ended up giving the child to a woman named Adina Roy, a blind old woman who had the child selling needles on the road from the moment Simone could get two words out of her mouth. Adina Roy was the one who had told the child the little she knew about her mother.

The file continued. Someone had found the child when she was four years old, her arm wrapped around herself, wandering the dangerous streets of the capital. The two-day-old dead body of Miss Adina Roy was found later. The autopsy showed her big heart had given out after a massive heart attack. The child never really spoke for years after that. And she kept having, on the evidence of what she drew, the same dream over and over again, of hundreds of thousands of needles falling down on her and digging deep into her body.

It took her, the woman who had adopted the child and brought her to America, two years, many psychotherapists and a young man with a bright yellow guitar in his hand and a multicoloured kerchief on his head to get the little girl to slowly, ever so slowly, open up like an early spring flower and begin talking. And the young guitar player with the flashing eyes did not get only the child to open up, but the child’s mother, too. For years after, the mother would tell anyone who would listen that the man, the guitar player, the one at a university getting an advanced degree in film studies, was her soul mate, the person she could tell anything to. She had never felt so close to anyone in her life. Before that man came along, she would tell her increasingly sceptical friends, she had been a tightly closed flower, but that was before the guitar player transformed her into a parrot tulip, bright red and yellow, in full bloom.

Within a month they had moved in together. Years later, she still could not understand why they had never married. But now the guitar player had taken the narrative thread of her life and tangled up the order of the sentences. Everything now confused and incoherent. Everything now up for question. Had anything at all been as it had seemed? And the young woman, her daughter? There was that letter sitting there and staring at her. Something about them being in love. The two of them moving to Europe together. She had always felt, the young woman, her daughter, that her mother had died giving birth to her seventeen long years ago. That she had never had a mother. And he, the guitar-playing lover, had told her that she, Simone, did not have an ounce of his blood flowing through her body, and since she was not his natural daughter…

How she knew the day, the exact time that she would find them, the two happy, laughing and giddy lovers at the Air France terminal at the John F. Kennedy Airport would be speculated about for weeks in the newspapers. Had the mother been going there day after day, hour after hour, after she had found the letter? Had she hired a private investigator to track them down, her lover and her daughter? But that day, there they were, feeding each other, the suitcases stacked like a pyramid beside them. Of course, nothing made much sense to her after that, and it would take her, the psychiatric social worker, days of reading through her own file to bring some coherence back to the jumbled narrative of her story. Days before, she read, she had bought a gun – there was yet another fierce battle in the New York newspapers for and against strengthening the gun laws – but, yes, she had bought a gun. One that did not have a silencer. As if she wanted the whole world to hear the shots she fired. They had both stopped laughing the minute they saw her, her daughter and her lover. He had gotten up to say something to her when she pulled something dark and powerful out of the deep pockets of the fiery red coat she was wearing.

She did not mean to kill the child, her daughter, but the child had flung herself between her man and her mother. That death she was sorry about, and would be for the rest of her life, playing it over and over again in her head as if it were her favourite sad song on some slow record player. But as for him, she told the officers who came running after they heard all the commotion, two bullets to his too beautiful face and the five more to his crotch, he was already dead by the time she killed him.

OLEANDER

It started with one tattoo. A tattoo of a flower. Or part of a flower. She came with a photograph, but it was no flower he had ever seen before. She wanted it here, she said, pointing to her navel; she wanted it surrounding what she considered the most important part of her body. She also wanted the exact same shade of colour. Since she was chocolate brown, he, the tattooist, had to play a little bit with the mixture. When they were both satisfied with what he came up with, the tattooist wrote the combination of inks and dyes into a book, so he would always remember. He knew that she would be coming back many times thereafter.

As he readied the electric machine, the tattooist explained that the ink would be inserted into her skin through a series of fine needles, that it would be over before she knew what was happening. Still, there would be some stinging and burning and a slight swelling. He made sure that she saw the gloves that he was wearing, that he opened a brand new pack of needles and wet disposable napkins. There were no risks of any kind of infection.

To make small talk as she took her clothes off, the tattooist told the young woman that though it was hard to tell, he knew she was a foreigner. Well, not a foreigner exactly, for who could really claim to be a native New Yorker? But there was a soft lilt to her voice, an accent that was somewhat muffled. Such thick dark hair, he thought, admiring the young woman. The dark-almost-to-violet eyes. As she lay back on the raised narrow bed, he gave her what he thought was the beginning or the very centre of a flower. He noticed how, after they were finished, she stared at herself for the longest time in front of the mirror.

She came back a few weeks later with another photo. This one showed even more parts of the pale pink flower. Though he could not see all the plant, he instinctively knew that this was a flower that bloomed profusely. He saw the five petals that were beginning to flare from a yellowish centre. Could he do this, she had asked, softly, could he enlarge her flower? She lifted up her blouse so he could admire the work he had already done, that first tattoo forming a ring around the rumpled dark spot of her navel. How well everything had healed! Such vibrant colours! As he mixed a new batch of colours, she told him that she was from Jamaica, that she hadn’t been home for such a long time that she could barely remember the outline and contours of the island, and she didn’t really feel right in still calling the island her home. The tattooist smiled to himself. He remembered the time, years before, when he’d fallen hard for an island beauty. Every time he thought of that woman, she was conflated into a vividly coloured flower. That day he extended the pale pink colour halfway across the young woman’s belly.

The next time the young woman came she wanted to round out the edges of the petals to a magenta colour. She wanted the sepals curving slightly. She wanted streaks of white mixed in with the magenta. The flower was now extending upwards to cover almost half of her body. When he was done, she kept looking at herself in the mirror, all the while mumbling, “Larger. No, larger!” He would keep working on her until the image started touching a rigid dark nipple.

The tattooist liked working on this woman’s body. How effortlessly the needle sank into her skin. As if it were the very best crushed velvet. How she sighed each time she felt the piercings, almost as if it were a release to have something enter her body painfully. She wanted him to tell her all he knew about the custom of tattooing. Something of what he said about “modification” and, especially, “branding” seemed to please her immensely. Then she asked him if it was true that the ink might fade one day, in the far away future? She seemed overly relieved at his answer. That, yes, the tattoo would fade, but no one could ever totally remove it from her body. When he said this, a calm relaxed look came over her.

The next time she came she wanted lance-like, dark-green leaves to go with the flower. She had done some research, she said, had found out that many people erroneously believed the flower to be a member of the olive family. She could understand why; the leaves they grew looked so much like each other. Indeed, the night before, she had dreamt that she was applying olive oil all over her body. But, no, this wasn’t some olive plant imitation flower. Anyone with any kind of sense would know that just because two things, two people, looked alike, that did not necessarily make them family. Family. In the soft lilt of her voice, she repeated the word over and over, even as he worked on the soft velvety canvas of her body, extending the flower to her back and then down her arms and legs.

But then the woman with the burnt-sienna hair had taken him aback when she told him she was working as a helper. He’d had her pinned down as someone’s spoilt, rebellious daughter. But, no, she told him; the work she was doing was as a housekeeper. Still, she must be paid handsomely, this woman who kept adding more and more parts of the strange and exotic flower to her body, for she never had any problem paying him what he charged – and he knew that he charged more than any of the other tattooists in the city. They must be some very rich people she worked for.

A couple of weeks later she told him that the couple she worked for looked just like her. Had, in fact, the same warm brown colour. Did he remember what she had said before about people looking exactly like you not necessarily being your family? They were both lawyers, this couple who she worked for, with a thriving practice somewhere in midtown Manhattan. She was lying on the flat narrow bed, and this time she wanted even more branches and leaves added to the now gigantic flower that was consuming, it seemed to the tattooist, her slim young body. After a while, it did not seem right to him that this flower just kept growing and growing, up and down her arms and legs, her back, breasts, belly and even surrounding her pubic area. Was the flower sucking the life out of this once-vibrant young woman? She seemed weak and tired when she came to see him. It was then that she told him. She was but a child when she had left – had been taken – from Jamaica. And never, not once, had she set foot on or been allowed to go back to the island. Yes, she said, in a hiss of a voice that could not hide her anger, there had been a few letters over the years from a woman who claimed to be her mother, but this woman only ever wrote her when she wanted something; only ever wrote to beg her money. But she was finished with that now, the young woman busy turning herself into a flower was saying, all she cared about these days, was the style and the stigma of her flower, it’s filaments and anthers.

Another day she started telling the tattooist a new story, which at first seemed to him a far-fetched, hallucinatory tale, except that she told it with so much detail and vigour. Of a little girl who had been given away by her mother. How this eight-year-old girl had just been handed over. The tourists, whom she called terrorists, had come to the island on a “visit”, but had ended up taking the frightened little girl with them back to America. All the promises they made to this little girl’s mother! How they would send her to school in America. How she would grow up to be a big-time doctor. The young woman told the tattooist how her mother had whispered in her ear that she was to go with these people, these strangers, and the little girl was to do what these people told her to do. They were her parents now. When the little girl started crying, her mother shushed her and told her to think of the other children. The little girl would never forget the thick wad of American dollars handed over to her mother by her new tourist/terrorist parents, and that her mother barely had time to say goodbye to her because she was so busy counting the money.

The things this couple did to the little girl-child from Jamaica! How for years she was never allowed to leave the house without one parent or the other with her. Even as she got much older. How it was that they, her “parents” – who kept handing her the begging-letters from Jamaica – also kept insisting there was no such place as Jamaica. The couple told her that her memory of a life on an island so many years before was all part of an overblown imagination, the same imagination that had landed her on the psych ward one time after another for making-up-stories-about-such-good-people. For years she could not sort out the truth of one story from the fiction of another.

The tattooist listened without saying a word when she told how one, then the other, and sometimes both together, the couple enjoyed her; not only enjoyed her but made of her a cardboard character, filming and photographing her; sharing her with friends who eagerly came over. Calling her this horrible name – Lolita. And when the tired weakened girl left him that day, the tattooist had no choice but to trawl the Internet until he found a picture of a hardy pink plant called the oleander – a plant that the young woman said grew in abandon in the yard of a lean-to, tin-roofed house of a bedraggled woman with too many children around her. After he found the plant he sat looking at it for a long time, the tattooist, knowing, instinctively, that this would be the last time he would see her.

TERRA NOVA

She turned to look at herself in the mirror. Legs falling away effortlessly from slender hips. This was why she always got whistles from men on the road, men who salivated when they saw her in the pants that seemed to have been sewn onto her. Yes, she admitted, she looked good, real good. That was until she turned to look at herself from the side. Then, her belly bulged slightly. Actually, more than slightly. She looked as if she were in the first trimester of a pregnancy.

When I heard the news I couldn’t believe it. I was standing in the yard washing baby clothes when someone came running up to me. I tell you my head started spinning. So many people seemed to be talking to me all at once. What was it that they were saying? Bus. Truck. Accident. Is like I couldn’t understand what was happening. I needed someone to stay with the other children in the yard who I was watching so I could go to Cross Roads and go get Aunty. Before you know it I was up the road. So many people just talking-talking. Then I got to the main road. A truck. A bus. A crowd. An accident. People whispering, “That’s the cousin who take care of them when the mother is at work.” The police came out of nowhere. Someone was holding onto me. They would not let me see my cousin.

Well probably her tummy was not as big as a first-trimester of pregnancy. It didn’t matter anyway. Certainly not for the man she was with last night. No, she wasn’t a hooker, she almost said to the reflection in the mirror. The one that was always standing there looking back at her, as if the woman in the mirror was the accuser of the woman outside of the mirror. And what was so wrong with enjoying her body, she asked the woman inside the mirror, the one who lived in a place she had come to call Terra Nova? She never took money from any of the men she was with. Not one dollar, she said, turning around to look at how tight her bottom was. She had the most perfect body. Everybody said so. Small and neat. What pleasure she could bring to others with her body! Contracting-then-letting-go. Letting-go-then-contracting. She smiled – that smug self-satisfied smile that some people accused her of.

It was on Spanish Town Road that the accident take place. That big busy highway. The one that done claim the life of so many adults, to say nothing of littlechildren. Especially near the passport office, which was where we were all living at the time. Sure the governmental people painted some white bridge across the road and call it a zebra crossing. As if that would help children! It certainly never help Marie. Dear sweet Marie. Buried now in Calvary cemetery. And every time… every time… I pass the spot on Spanish Town Road, all I can remember is the police holding onto me. The truck driver sitting hunched over. The bus driver with his eyes too-wide open. “The little girls,” the bus driver kept saying, “the two innocent little girls!”

She looked closer at the mirror. It seemed cracked right down the middle. No wonder she thought something strange was going on. As if she had cracked right in two. How long had that crack been there, in the centre of the mirror? As if one part of her had been smiling, while the other side looked on angry, accusing. She would have thought her mother would have said something about it. But her mother had chosen to say nothing. In fact, her mother had stopped talking to her that day Marie died twenty long years ago. Of course she didn’t just up and stop talking to her right away, but looking back at it, it seemed as if her mother never held another real conversation with her after that. Just a word here or there, nothing more. Never mind. She would not worry about that now. That was all behind her.

She pulled up a chair in front of the mirror. It was midday and the light pouring into the room seemed to surround her. A thought entered her mind and she pushed it away. But it entered her mind again, this time more forcefully. Soon she started to giggle. She opened her legs, slowly at first, before she flung them wide open. And there it was, the bright pink thing that gave her so much power.

The truck driver was in the wrong. That was what everyone said and that was why, that day, he had been sitting by the side of the road, his head hanging down and wringing his hands. He knew he would be going to jail. They tell me the bus driver had stopped, to let the little girls cross the road. The bus driver said later that they reminded him so much of his own two children. They tell me the bus was packed and hot, and the people were complaining. Some craned their heads through the window to see what the bus driver had stopped so long for. That was when they saw them, the two little girls in their yellow and white uniforms, crossing the road, holding hands. The people who saw them couldn’t have helped but smile. The younger one, Marie, would have raised her hand to wave at them and give them a little smile. Marie was always like that. What would she have known? Did a shadow fall across her face?

She looked closer. Then even closer. There wasn’t only one crack in the mirror, but many. So many cracks that now it seemed as if there wasn’t one her that was rising to examine the mirror, but herself all fragmented. A breast here. A leg there. She remembered the time when her mother caught her. She must have been sixteen then and just growing into her body. Her breasts were unfolding nicely, her hips rounding out. For some time boys had been paying attention to her and sending her notes. And, to tell the truth, she had let the boys she liked touch her. Put they fingers far up into her webbed interior. She did not know how much her mother knew of what she was doing, after all, her mother was rarely at home and spent all her time going to the cemetery to visit Marie. When she was at home she was always crying. But that time when her mother came home suddenly there was no getting away for her, or for the boy hunched up naked in the far corner of her room, from the words her mother flung at her. “Slut. I wish it was you and not your sister who died!”

Everyone remember differently how Marie looked in her coffin. For me it was something I hope to never see again as long as I live. I was sorry I ever look in that coffin. No matter how hard I try to get that picture out of my mind, I can never forget it. It was the same way that I could not get them to stop what I considered a bad spectacle. Aunty was there, looking down at her dead daughter in her coffin, murmuring about what an amazing job they had done with her face, how Marie look peaceful, like she sleeping. I remember everything quite differently. Yes, Marie was in a pretty frilled white dress like Aunty always remember; but even though we give the mortician a photograph, there is only so much you could do against tons of steel on a fifty-pound little girl’s body. It would have been better, I always say, if they had given the child a closed casket.

Never mind the broken parts of her that were now confronting her from the mirror, she was pretty. Of that she was sure. People wanted her. Men wanted her. She loved it when they told her how much they loved her. In the upscale hotel that Carl took her to last night, Terra Nova, he had told her over and over again, as she contracted-and-let-go, how much he loved her. How he could not live without her. How the fat red wife he had at home could not hold a candle to her. Yes, that was what Carl told her as he entered her. So never mind what her mother said about she was a slut and that she wished she was the one who had been crushed by that truck. None of that did not matter. No, none of that did not matter at all.

I am not no big-time specialist or pastor nor nothing and I can’t talk and give advice to anyone over the radio. But I think parents should be careful how they talk to their children. Yes. Like they say in church, parents must be careful ’bout the messages they sending. Mothers in particular, for ninetypercent of the times is the mother alone raising children on this island; the fathers just gone, don’t even look back on their children. So mothers in particular have to be careful. That is why I think Aunty never treat Cicely right after Marie died, never treat Cicely like she supposed to treat her. Aunty spend all her life crying over Marie, who she always said was prettier. And Cicely, she try to do everything to please her mother. But all Aunty do is call Cicely all kind of bad name. Saying that she is a slut. Saying that she wished the truck had flattened out her head instead of Marie’s. Terrible things like that. Like I say, I am no radio specialist and cannot talk to people much, but I know that must hurt. Is true, Cicely have a lot of man. But if the man in the radio is right, the one they say is a specialist, the one people call in and talk to, and I listen to them talk everyday, if that man is right, I know that Cicely looking for something, something that her mother never give her. Even I, fool fool as I am and living back in the country, even I know what Cicely is looking for from all those men, even if Cicely herself don’t know. She was crying when I talk to her the other day on the brand new cellular phone she send me from Kingston, crying, she said, she don’t know for what reason. But I know why Cicely crying, even if she don’t know, or what she looking for when she keep telling me some foolishness about how this man love her and that man love her, and she have so much power. Poor Cicely is all I can say. Poor, poor Cicely. Her mother never done right by her.

A GIANT BLUE SWALLOWTAIL BUTTERFLY

Scott saw it the moment he opened his eyes. He immediately closed his eyes and hoped that when he opened them again, the menace with its cobalt-blue wings would be gone. It didn’t even look like a real butterfly, the thing perched on the cream-coloured walls with such large blue wings.

No, it looked more like a hummingbird, one of those bright and colourful birds he had seen on his first trip to the island of St. Sebastian a couple of years before. How taken he’d been with the tiny bird, the rapid fluttering of its wings, the long arched beak and the dazzling colours.

To this day, whenever he thought about a hummingbird, he saw streaks of magenta, emerald, silver and a long thin beak pushed deep into a bright red flower. He had been fascinated, wondering what would happen if the serrated petals of the hibiscus flowers folded over, covering the tiny bird. Would it suffocate, or would it know how to use its beak to break free of the flower? He was looking out of the hotel window. Beyond were the many shades of blue of the island’s waters, nearer were the trees and the many different flowers. The hummingbird, with its tall thin beak still deep inside the flower, was almost close enough to touch.

Perhaps he could catch it, he’d thought, getting up stealthily from the bed where the woman’s body was still curved in sleep, perhaps he could hold this bit of magic in his hands. And he would have done it too, was almost upon the tiny bird when the woman stirred, and called his name, startling the bird, which immediately flew away. How irritated he was with the woman after that. So much so that for the rest of the vacation he kept pulling away from her, wanted her to leave him alone, telling her he had to catch up with his reading.

When he opened his eyes again the butterfly was still sitting there and looking at him. Who could he tell that he was being menaced by a giant blue butterfly? That every morning for the last two years it had been on the wall looking down at him. Was it his imagination that the stupid butterfly was laughing at him? Or was it loneliness and sadness that he saw in the butterfly’s dark eyes? No, he decided, the butterfly was not sad or lonely. The insect was laughing at him. Well, no one laughed at him, he mumbled, getting out of bed. Only days before he’d gone to Home Depot and bought a large butterfly catcher, which now leant up against the refrigerator in the kitchen. He would show that butterfly. But by the time he came back, the butterfly was gone. He spent half an hour looking for it before he gave up, defeated. The butterfly had outwitted him again.

It was in St. Sebastian that he met Dora. She was one of the girls sitting in the bar in the evenings when he went down to get a drink. When they finally got together, he made it a point of honour never to ask Dora what she was doing at the bar night after night; he did not want to know the answer to that question. But there she was, the six nights that he was on the island, chatting up the bartender, a colourful drink in her hand, a big bright red flower behind her ear.

He knew she was aware that he kept looking at her, never mind that he had come on his vacation with a woman – a young woman who worked on a student program in New York, a young woman he should be paying attention to, but Rachel just did not hold his interest. What he wanted to do was get to know the woman with the big red flower in her hair leaning against the bar. He wanted to know what she told the bartender to have him smile just so.

Back at home, the butterfly was still on his mind as he made his way to work. Staring down at him as if it were both judge and executioner. No, that was not right, the butterfly acted as if it were a lawyer, looking coolly at him and waiting for some kind of answer as to what he had done with his life. Why had he never married? Why didn’t he have any children? He decided that he didn’t like lawyers, even though he was one. Well, he wasn’t really – he had gone to law school but hadn’t practised.

He was really a union man. A David throwing his stone at mighty Goliath. Just now, his little team was up against a gargantuan private university that did not want to pay its adjuncts a living-wage. What irked him even more was that the adjuncts they were treating so unfairly included those who taught on a “special program” that catered for poor students and students of colour. He could not and would not lose that case. He was transported back to the day he graduated from law school, a juris doctor no less.

“Finally,” his grandmother had said, wiping her eyes, “finally we have a doctor in the family.”

Well that was what he wanted for those poor and those black students; that one day someone else would get to say, “Finally, we have a doctor in the family.”

But here now, in his car, was the blue butterfly. How could it have gotten in? The cussed insect must have followed him from home! So, had it taken to following him around now? The fluttering blue thing. Next thing he knew the creature would be in his office. No, he could not allow that to happen. Using one hand to keep driving, he went after the butterfly with his free hand. When that did not work, he went after the butterfly with both hands. It took the violent swerving of the car and the horns from all the other drivers to bring him back to his senses. He could have killed himself going after the creature, but still it got away.

He had gone back to the island and stayed in the same hotel where he had stayed with Rachel. The woman who he had first seen leaning against the bar with the big red flower in her hair was still there, as if waiting for him. He sidled up to her. “Hi, my name is Scott.”

The woman had looked him up and down, as if she was trying to make up her mind about him.

“Dora,” she said, after a while.

“Can I get you something to drink?”

Again she looked him up and down.