8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

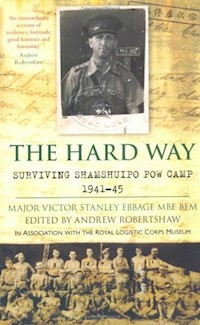

Major Vic Ebbage was a Colonel with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, serving in Hong Kong in 1941, when his garrison was attacked by the Japanese Army. He was captured and taken prisoner to the notorious Hong Kong death camp, Samshuipo, where he was held from 30th December 1941 to August 1945. His story is an extraordinary one of survival against all the odds, but more than that it is a story of how a group of men worked together to improve conditions in the camp for their fellow prisoners. They were offered nothing by their captors, but their constant command of 'improvise', which they learned to do by recycling salvaged materials into everything from homemade nails, cooking pots and plates to surgical instruments, beds and nesting boxes. His diary demonstrates how individuals can work together in almost unimaginable adversity to improve life for their fellow man, and how imagination and innovation can flourish in even the worst conditions. This story is a model of care, humanity and inventiveness.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all members of No. 6 Section, Royal Army Ordnance Corps who served in Hong Kong 1939-45, and in particular to those who gave their lives while fighting the Japanese, or while Prisoners of War, or who succumbed after release. For all were ‘Gentlemen of Ordnance’. And also, in grateful thanks to the Red Cross, to whom so many who survived captivity owe so much.

Note: The numbers making up the Section in Hong Kong at the outbreak of War with the Japanese was about 150.

DISCLAIMER

The text of this book is true to Captain Ebbage’s original typescript. Only slight changes have been made for consistency and readability, but his original sentence structure has been retained. Any additions in square brackets are to enhance the meaning of certain sections and have been added by the Publisher or Editor.

Acknowledgements

This book is the result of the hard work and dedication of its author, Victor Stanley Ebbage. The Royal Logistic Corps Museum is grateful to him for his decision to deposit the typescript in our archive in the expectation that the museum could at some future date get it published. This process was greatly assisted by the author’s daughter, Miss Joyce Ebbage, who gave her full support to the project and provided the editor with additional genealogical information and a number of photographs.

The starting point for the book was a search of the museum’s archives by staff who were looking for information about the experiences of members of the Royal Army Service Corps and the Royal Army Ordnance Corps as POWs. It was Adam Culling and Melanie Price who brought the material to my attention and they deserve my gratitude for their diligent research. As parts of the book used a large number of Chinese place names, some of which are now spelt differently than they were in the 1930s, I recruited Shirong Chen, an old friend from the BBC to help with translation. Tony Banham, expert on the defence of Hong Kong and the experience of the POWs between 1941 and 1945, generously shared his knowledge, having been contacted by me, ‘out of the blue’, and was an extraordinary resource. A final thanks goes to the staff of The History Press who recognised the value of Major Ebbage’s account and agreed to its publication.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Editor’s Note

Major Victor Stanley Ebbage MBE, BEM: A Brief Military Biography

Foreword by Major General G.L.F. Payne

Preface

Maps and Plan of Shamshuipo

1.Chaos

2.Some Order out of Chaos

3.‘Improvise’

4.Exodus to Argyle Street

5.Affidavit

6.Letters Home

7.The Steam Oven

8.The Party System

9.Parsons & Books

10.SS Lisbon Maru

11.Working Parties

12.Red Cross Supplies

13.Pig & Poultry Farm

14.Propaganda Draft

15.Term Report or Salt Pans

16.‘Albert’ or Intelligence Tests

17.Christmas 1943

18.Ladder Bombing

19.Return of Friends

20.Money Matters

21.Japanese Surrender

Appendix 1: Report by Captain Ebbage, RAOC

Appendix 2: Report on RAOC by Prisoners of War of Japanese in Shamshuipo

Endnotes

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Editor’s note

One of the advantages of being a museum curator is the opportunity to see artefacts and archives that have not previously been seen by the public. In the past when items were donated by members of the public, a record was created and, all too often unless it went on display, the item was put into storage. The fact is that all museums have more objects than they can display and the archives consist of so many documents, photographs and other items that have to be kept in temperature- and humidity-controlled stores. However, one part of the mysterious work of museum curators and archivists is systematically going through collections, correctly cataloguing the items so they can be of use to current and future historians. In doing this occasional ‘gems’ are found: objects or collections that stand out and are so remarkable that they clearly cannot simply stay in store. This was the case with the collection of documents and photographs belonging to Major Ebbage which was brought to my attention by two museum staff members, Adam Culling and Melanie Price, when they were looking for information about the activities of the predecessor Corps of the current Royal Logistic Corps in Hong Kong. Subsequently Gareth Mears, the Archivist, located other items related to Major Ebbage and specifically his period as a Japanese Prisoner of War (POW) in Hong Kong.

As I read Major Ebbage’s story of his early life, career and time as a POW I was struck by many coincidences that linked my non-military life with his military career. He was born in Leeds, where I spent my early years and he was sent by the army to Shanghai, Hong Kong and Beijing, places to which I have travelled and know well. This gave me some idea of his travels, but nothing could prepare me for his account of life in Shamshuipo POW Camp, Hong Kong, between 1941 and 1945.

He survived a battle in which his commanding officer and many other comrades died, and tried to evade capture, but was forced to surrender. Within hours of being taken prisoner, he was acting as liaison officer between his comrades and captors, travelling with them to the site of a battle in which he had been a lucky survivor, and then having tea and a chat with Japanese officers in a hotel with a sea view, all in the same day.

He then found himself responsible for the other ranks of Number 6 Section Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) in camp ‘S’ (Shamshuipo), when the other officers were sent elsewhere. For four years, despite starvation, privation, brutality and ill-treatment from his captors he did some remarkable things. Not only did he keep the men busy, but moreover he did so with useful activity. No opportunity for improvising appears to have been missed and if today ‘recycling’ and ‘sustainability’ are the watchwords of modern society, it is quite clear that the Major and his men were well ahead the rest of us.

He is modest about his attempts to maintain morale and also acknowledges the efforts of those of his captors who attempted to be fair. Critically he praises the work of others, especially the Red Cross, in ensuring that the prisoners survived. It is a telling point that after his release in 1945, one of his first acts on his return to the United Kingdom was to write to the relatives of every man in the section who had been killed or died.

I never met Vic Ebbage, although I wish that I had – it would have been a fascinating meeting. He wanted his story to be told, but for various reasons his account was not turned into a book in his lifetime. This publication, seventy years after the fall of Hong Kong, allows this to happen. I hope that his account of resilience, fortitude, good humour and humanity will be of interest to an audience who are perhaps more familiar with celebrity status and glamour than duty and self sacrifice.

Major Victor Stanley Ebbage MBE, BEM

A Brief Military Biography

Victor Stanley Ebbage was born in Beeston, Leeds on 13 August 1901, the son of Thomas Henry and Rose Monica Ebbage (née Grimshaw).1

Thomas Ebbage worked as a clerk for a local railway goods company and according to the 1911 Census the family also had a daughter, Phyllis, who was just a year old. Their address at this time was 20–21 Lanes End, an area of terraced housing and industry which did not survive German bombing in the Second World War or the post-war redevelopment.2

Victor had an aptitude for learning; however the death of his father in 1912 from tuberculosis, aged just thirty-four, meant that like most children of his background and generation, he left school in July 1914. He was able to leave school aged nearly thirteen because he was ahead of most of his classmates and had acquired the required standard of elementary education.3 He found work as an office boy in the office of his uncle, Sidney Grimshaw, and his income would have been welcome for a now fatherless family.4

Victor was witness to the momentous events of the Great War on the home front, which broke out only a month after he started work. Leeds was the scene of effective recruiting drives throughout 1914 and 1915 and many of the young men who joined the Leeds’ Pals Battalion and other local units would have been well known to him. He was, however, too young to serve as the conflict ended before his nineteenth birthday which would have given him the opportunity to volunteer or be conscripted.

After the war Victor’s mother was able to gain employment as a book keeper for a woollen merchant and this provided Victor with the opportunity to take up a new and more challenging career.5 After just less than six years of office life he enlisted into the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) as Private 7576720 in his home city on 1 March 1920.6

His initial period of training was at No. 2 Section RAOC Tidworth in Wiltshire. He was sent for his first overseas service on 13 October 1920 in what was then Mesopotamia, today Iraq.7 In 1920 the region was controlled by Britain as a Mandated Territory under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. In the spring of 1920 there was a revolt against British rule, which started in the capital Baghdad. During the unrest that followed over 500 British and Indian troops were killed. Victor served in and around Basra (the focus of events in a more modern conflict involving British soldiers). Within a year, on 1 December 1921 he was promoted to Lance Corporal without pay,8 although he had to wait until July 1923 before his promotion to Lance Corporal with pay.9 For his overseas service he was awarded the General Service Medal (GSM) with the Iraq Clasp.10 On his return to the United Kingdom he was posted first to Bramley in Hampshire11 and then on promotion to Corporal for two and a half years to No.10 Section RAOC Burscough in Lancashire.12

It was during this time that he demonstrated the academic promise of his younger years, which had been frustrated by the premature end to his education in 1914. He generously ascribes this success to the care of various Army Schoolmasters and others.13 He was promoted to Lance Sergeant in October 1925 and gained a 2nd Class Educational Certificate in December of the same year.14 By June of the following year he had gained a 1st Class Educational Certificate, having distinguished himself in mathematics, and was eligible for the examination for promotion to Sergeant.15 He passed the examination and was promoted to Sergeant in March 1927.16

A month later he was, once again, sent overseas. This time the destination was the Far East, as part of the newly created Shanghai Defence Force.17 In early 1927 the International Settlement in Shanghai was in danger of being captured by warring Chinese armies and the local forces available were insufficient for the task. The British government sent a division to secure the settlement and protect British lives and property. This force included elements of the Royal Army Service Corps and RAOC to deal with stores and ammunition. Presented with this show of force the situation rapidly stabilised without serious fighting and it was possible to withdraw all but a single British battalion which remained as the Shanghai garrison.

On his return home, in 1928, he saw service at a series of Ordnance installations including Hilsea in Hampshire, Stirling in Scotland, Barry Camp in Wales, Didcot in Oxfordshire, Woolwich Arsenal and Chilwell in Nottinghamshire. He had clearly been intending to marry for some time as he applied for married quarters in August 1927,18 but was still on the waiting list when he married Elsie Iddon on 23 April 1930 at Ormskirk in Lancashire, not far from her family home.19 Their first child, Elsie Joyce, was born a little under a year later on 19 February 1931, while the family were quartered at Stirling, Scotland.20 It is during this period of his service that he is frequently mentioned in the journal of the RAOC in connection with not only success at billiards, but also organising events such as dances and other music events.21 Mrs Ebbage is not absent from the accounts of sporting accomplishment and in July 1934 she won the Married Ladies Race at the Didcot sports meeting.22

By September 1933 shortly before the family moved from Stirling to Didcot in Oxfordshire, Ebbage had passed the examination required for promotion to the rank of Warrant Officer Class II (Staff Quartermaster Sergeant).23 This promotion did not occur until 29 January 1936.24 However, in the same year he was awarded the Medal of the Military Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (RAOCG now known as the BEM) and promoted to Warrant Officer Class I (Sub-Conductor).25 The award of the BEM was related to a one year period which he spent at Woolwich in connection with, the then very innovative development of, machine accounting.26

The expansion of Japanese influence into China from 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War directly threatened British interests in the region. In addition to Hong Kong there were British units in Shanghai, Tientsin and Peking (Beijing), as well as a rest camp at Shanhakwan. On 24 February 1938 with the threat of war growing, Sub-Conductor Ebbage was drafted for service in Hong Kong and his farewell concert was held at Chilwell.27 He and his growing family (Mrs Ebbage was heavily pregnant) went to the Far East on His Majesty’s Transport (H.T.)Dilwara.28 A son, Kenneth, was born on 19 July 1938 shortly after their arrival in Hong Kong.29 More good news followed when he was promoted to Conductor in October 193830 and received his Silver Medal for Long Service and Good Conduct from Major-General A.E. Grasett, DSO, MC in March 1939.31

By now, the family had settled down in Hong Kong, buying furniture and securing the services of a local Amah (nanny) for the children. In July Conductor Ebbage in company with Staff Sergeant Morries travelled to Japan for a three-week ‘holiday’, staying in Kobe.32

The outbreak of war with Nazi Germany led to the expansion of British forces and the need for additional officers. On 12 February 1940 he received an emergency commission as a Lieutenant, almost twenty years after he entered the RAOC as a private.33 His first appointment was as a member of staff for the General Officer commanding Shanghai. His post was Deputy Assistant Director of Ordnance Services, Shanghai and Tientsin. This brought with it the responsibility for removing large quantities of small-arms ammunition held in the magazines at Beijing, which due to the removal of British troops were no longer required. However this ammunition was needed at Singapore and Hong Kong.34 Once again his small family was on the move and aboard the vessel Wo Sang they arrived in Shanghai. The family initially lived in the Palace Hotel at a time when shootings and public disorder were all too frequent.35

In March, Lieutenant Ebbage was sent by ship to Tientsin, North China via Weihaiwei. From there he travelled by rail to Beijing. Having made initial visits to the magazine where the vital small-arms ammunition was stored, he returned to Shanghai to report the situation and get permission to attempt a ‘rescue’ of all the useful ammunition.36 Whilst back in Shanghai he tried to make arrangements for his family to move into their own accommodation. Shanghai was now an extremely dangerous city, surrounded by the Japanese, and European forces had established concession zones which were run according to their own rules.37

A second visit to North China in late spring took Lieutenant Ebbage to the British rest camp at Shanhaikwan on the coast and then back to Peking. Here he survived an attack from a mob by taking refuge in the American Embassy, and managed to persuade a Japanese delegation to examine ammunition stored in the magazine at the British Legion. Some of the mortar bombs had been damaged in flooding and Lieutenant Ebbage managed to eventually persuade the Japanese that to prevent a potentially catastrophic explosion it should all be removed and dumped at sea.38

Having returned to Shanghai to report his success he also finally secured a home for his family. During another journey to Peking Lieutenant Ebbage was able to supervise the removal of the ammunition from Beijing and the dumping of the dangerous elements into the sea. The ship involved then headed to British territory still carrying thousands of vital rifle and machine gun bullets under the noses of the Japanese against whom they would later be used.39 Yet another journey to North China was followed by the apparent opportunity for a family summer holiday in Korea, away from the increasing confusion and violence in Shanghai. These plans came to nothing and following the evacuation of many of the British families from Hong Kong it was decided to also evacuate those British families in Shanghai to safety. Mrs Ebbage and the children embarked on SS Tanda bound for Australia on 23 August 1940.40

Following a final, farewell journey to Beijing, Tientsin and Shanhaikwan, Lieutenant Ebbage returned to Hong Kong in September 1940 as part of No. 6 Section RAOC. He was promoted to Captain and became Officer in Charge of Provisions and Local Purchase.41 He was sharing a flat in 3 Gap Road with Captain Burroughs, who was later killed during the fighting on Hong Kong Island.42 The Japanese attacked the Colony of Hong Kong on 8 December 1941. Once the Japanese breached the defences on the mainland the main Ordnance Corps depots came under attack and some storehouses were destroyed. Although the magazines were under shell fire and aerial bombardment, the bulk of the explosives were moved to safety. Captain Ebbage had a lucky escape on the morning of 10 December when a Japanese shell exploded close to where he, Colonel MacPherson, Captain Burroughs and Lieutenants Hanlon and Sutcliffe were gathered in an office 15 yards away.43 By early on 13 December all British troops had withdrawn from the mainland. This however exposed the Lyemun Magazine and Married Quarters to heavy Japanese fire across the narrow straight of water separating the island from Kowloon. Captain Ebbage was directed to take charge of a party which transferred all the stores from the Married Quarters to the Ridge on 11 December.44 He was in command there until the later arrival of Lt Colonel MacPherson.

The Ridge was a key position in the defence of the island as it lay on the route between Repulse Bay and Wong Nei Chong Gap, both places at which heavy and prolonged fighting took place. The work of moving the stores was carried out under heavy shell fire and the RAOC drivers involved were all volunteers.45 Most of the stores were in position by 17 December and some ammunition was handed over directly to gunners at gun positions. Although the initial Japanese assault on 15 December was beaten off with heavy losses they managed to make their first landing on a broad front on the night of 18/19 December.46 Parties of Japanese soldiers moved rapidly inland cutting off various units and occupying the vital Wong Nei Chong Gap. From here they were able to advance on Repulse Bay, Shouson Hill and Little Hong Kong, cutting the island in two. The first Japanese soldiers were seen near the Ridge on the 19th and a party of their soldiers was engaged with machine-gun fire with some effect. By now a mixed party of Royal Engineers, Royal Army Service Corps, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps and Royal Army Ordnance Corps were defending the Ridge.

These troops, numbering about 280, used nearby houses and bungalows as improvised strongpoints with the men divided between these, and a proportion of officers allocated to each. A party of men under Lt Colonel Frederick, RASC, attempted to leave on the morning of 20 December but were attacked and many were killed or wounded. Some returned to the position on the Ridge and a few escaped to the hills.47 The remaining men on the Ridge were joined by the remnants of a Chinese battalion and other stragglers.48 On the evening of the 20th instructions were received for the personnel on the ridge to break into four groups. Two parties of eight officers and eighty other ranks were detailed to help hold the position, allowing the third group to make for Repulse Bay. The last group including Captain Ebbage was detailed to wait until the road to Repulse Bay had been cleared and then evacuate the Ridge.49 By the following day it was virtually impossible to move because of heavy Japanese fire and the order was received to stay at the Ridge because Canadian troops would be arriving. Around sixty members of the Canadian Royal Rifles arrived during the night under command of Major Young.50

Captain Ebbage reported that although it was possible to receive messages by telephone these were now in French as it was believed that the lines were being tapped by the Japanese.51 With the weight of fire increasing from machine guns, mortars and artillery, casualties began to increase. At 5pm on 22 December the commander of the detachment, Lt Colonel MacPherson decided to surrender but told those who wished to make their own way to Repulse Bay.52 Despite a flag of truce, firing continued and Lt Colonel MacPherson was mortally wounded around 3pm.53 Some officers and men managed to slip away, but the men under Captain Ebbage found it impossible to leave House No. 1 which was ‘continually riddled with machine gun fire’.54 After dark a party under Captain Ebbage left the position at 7.40pm with the intention of making their escape to the relative safety of Repulse Bay. Although the party headed by Captain Ebbage made for the Repulse Bay Hotel, only three – Armament Sergeant Major R.A. Neale, Quarter Master Sergeant (QMS) James Edward Cooper and Ebbage himself – made it to the hills. This small group remained hidden from the Japanese until the following night, 23 December, when in an attempt to get past the Repulse Bay Hotel, Sergeant Major Neal was believed to have been killed. This was confirmed by the two remaining men around 8pm on the following evening when his body was found.55 Although there was evidence that other members of the party from the Ridge were in the area, the two made their way into the hills to avoid the Japanese. At the time of the official surrender on Christmas Day, QMS Cooper and Captain Ebbage were trying to evade capture. The two of them survived without food or water for three days before they finally surrendered at 8.30am, 28 December.56 During this time many of his fellow officers believed that he had died in the fighting on the Ridge. He was also not aware until he was reunited with his comrades that of fifteen officers and 132 other ranks of the RAOC who were in the garrison of Hong Kong, only ten officers and eighty-nine other ranks had survived. This represented a casualty rate of 33 per cent, higher than any other unit in the Command. Many of the prisoners and wounded on the Ridge were massacred after the collapse of resistance and few like Captain Ebbage were able to escape.57

As a POW he was held in Shamshuipo POW Camp (Camp S) from 30 December 1941 until the Japanese surrender on 16 August 1945. Although he spoke no Japanese he became the liaison officer with his captors and remained with the men of No. 6 Section RAOC in Shamshuipo Camp.58 During this time many fellow prisoners had reason to be grateful for his efforts to make life in the camp more bearable. On his release from captivity he returned to the United Kingdom by sea, to Liverpool, where he was reunited with his family after a separation of nearly five years.59 After debriefing he was posted back to 14 Battalion RAOC at Didcot. One of his first tasks on his return was to write personally to the relatives of all the members of No. 6 Section RAOC who had been killed in the defence of Hong Kong in 1941 or who had died in captivity.60 His services whilst a POW were rewarded by his appointment as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in April 1946.61 Captain Ebbage survived a car accident near Didcot in 194862 and was made a Major in June 1949.63 In 1952 he was appointed to the War Office as Deputy Assistant Director of Ordnance Services (DADOS) and he finally retired on 1 September 1956.64 He was then re-employed as a Retired Officer in the Ordnance Directorate until his final retirement, after nearly 46 years’ service, at the age of sixty-five in 1966.65 Earlier that year he had returned to Hong Kong with fellow former POWs to attend a commemorative service and reunion.66

In retirement he kept in contact with the Corps and old friends, attending functions for as long as he was able. He devoted his spare time to gardening and voluntary work, and for many years was President of the Woking Branch of the Royal British Legion and member of the Far East Former Prisoner of War Association. The Royal British Legion Sheltered Housing Association built a block of flats in Woking and named it Ebbage Court.67 He died at home in Woking on 8 August 1990, aged eighty-eight, leaving a son, Kenneth, and daughter, Joyce, who had cared for him in the final years of his life.68

Foreword

Major General G.L.F. Payne, CB, CBE Former Director of Ordnance Services and Colonel Commandant Royal Army Ordnance Corps

I have known Major Vic Ebbage for a number of years – since 1954 in fact – when we began a close association in Whitehall. I always had the most excellent advice and support from him, and from other Ordnance Executive Officers of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, and I eventually became Director of Ordnance Services and subsequently a Colonel Commandant.

They were a fine body of men, and an outstanding example is that of the ‘Chief Clerk’ in this book. Not only was Major Ebbage a true professional in the best sense, to whom many came for advice, but he presented a most likeable and cheerful personality to all of whatever rank who came into contact with him. He was indeed a legendary figure.

Readers of this book will no doubt conclude that he must also have appeared in a similar light in the prison camp in Hong Kong, where he represented the needs of the prisoners, in attempting to make life under the Japanese as bearable as possible. Knowing him as I do, I am not surprised at the modest way in which he hints at the trials and tribulations with which he was faced in all his dealings with the Japanese. The prison guards no doubt did their utmost to degrade and denigrate their prisoners as much as possible, and what they did was made easier for them by Japan not being a signatory to the Geneva Convention.

From the very factual account in this book of what life was like for the prisoners under these conditions, one can but have the very greatest regard for the bravery, fortitude and inventiveness of these men, and the men of No. 6 Section, Royal Army Ordnance Corps were not least in these respects. A number of these men who showed such skill and inventiveness had been, in 1942, transferred to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, but this fact was not known at that time. At all times Major Ebbage’s thoughts must have been first for the men of his own corps, including those who were subsequently transferred to Japan. There must be many who were prisoners then, who remember his attempts to make life more bearable for them with gratitude. Later, after the war, others like myself regarded it as a privilege to have known such a gallant gentleman as Major Vic Ebbage.

Major General G.L. Payne, CB, CBE, Retd

Fishbourne,

West Sussex

February 1986

Preface

Author’s Note

In the early 1950s when my retirement from the army was drawing near, much thought was given to the future, how and where my family would live, and how I should spend my time.

Three things stood out; I wanted to have a house and a garden, do some voluntary work, and write about my life in the Army. As the day of my departure from service life grew closer, the realisation I had no home, or money, and insufficient pension settled the issue. If I wanted a home I needed a job to pay for it. So for nearly ten years after retirement from the Regular Army writing had, perforce, to take a back seat, but during this period I was able to concentrate on my garden and voluntary work. In any case my writing, in the shape of an autobiography would be of little interest outside my own family, for whom it had primarily been intended, after my death. My literary ability was nil, while my grammar reflected my lack of educational background. I had left Junior School just prior to my thirteenth birthday in 1914 for work as an office boy, and had progressed from there, with some help from army schoolmasters and others, and an ever widening knowledge of the world.

There might be a tale worth telling, but there were limitations on my ability to tell it! During that extra ten years of work I was able to look at matters from a different angle. I now had a house and nearly a third of an acre of garden; was immersed in voluntary/social work; had an ailing wife, and one or two problems with my own health. The History of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps 1920–45 did not contain any reference to periods spent as Prisoners of War. For that reason I resolved to give this part of my story priority; even more so because others gave me much encouragement to do so. As a result I reserved the three coldest months of the year (when confined to the house) to writing, research, typing, etc. What I thought would take but a few weeks became months and then years; the task seemed never-ending, and instead of being a simple straightforward biography, the work was becoming very much more!

As writing progressed I came increasingly to appreciate two factors:

a.The great talents, ingenuity, unselfishness, courage and loyalty of men of my own, and other units who, while Prisoners of War were prepared to do so much for others. No. 6 Section, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, to which I belonged, included many officers and men who had been officially transferred to the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers on its formation in 1942, but who remained ‘RAOC’ and wore this cap badge until the end of 1945, when they returned home.

b.Of the work done by the Red Cross to alleviate our lot, under the most difficult and trying conditions they had to face in Hong Kong, and the Far East. They receive so little praise (and do not ask for it). Had it not been for the supplies of food, clothing, etc which came into Shamshuipo Prisoners of War Camp in November 1942, and kept us going for many months, I feel sure there would have been very many more deaths, and I might well have been one of them! If therefore, my comments in the following pages appear harsh, ungrateful, and possibly unjust to the Red Cross and its representatives, my praise for them is unstinting and wholehearted - for, by their effort they saved many lives!

Individuals have not been mentioned by name, but some may be alluded to in different ways; nor are the sequence of events necessarily in the correct chronological order.* The account is as accurate as I can make it, taking into consideration that the happenings related occurred many years ago. I did not keep a diary, just a few notes, but have had access to records, papers, etc and the benefit of details supplied by my friends, which also enabled me to refresh my memory.

I have written my memoirs because I think that the story I have to tell might be of interest and benefit to others. It was written without thought of personal gain or aggrandisement, and for this reason it will not be published in my lifetime. In my advancing years, and when I was not physically capable of more exacting work, it has provided me with an outlet, or therapy, for my still active and fertile brain. The account is as factual as I can make it, taking into consideration that the happenings I have related occurred many years ago. I did not keep diaries, and indeed there were times when this was not possible; in particular, my sojourn in a Japanese Prison Camp, but I have had access to certain papers and the benefit of details supplied by friends, in particular about Shamshuipo,1 which have enabled me to refresh my memory.

Most of my adult life has been spent in the service of the Crown; nearly forty-six years in all, from very junior Private Soldier to Commissioned Rank.2 It is natural therefore that most of my story deals with my life in the army. My unique career covers a wide variety of experiences and activities; during the run down after the First World War; preparations for the second; a personal narrative of the defence of the Ridge during the war against the Japanese in Hong Kong; and the aftermath of the Second World War as well. This part of my story may have particular interest to those who serve the Crown now, or may do so in future, and especially those members of the RAOC3 in which it was my honour to serve for so long. I hope it will bring no benefit or comfort to the enemies of our country.

I have called my story ‘The Hard Way’ because that is just what is was. The climb from obscurity to a position of power, if not in rank, was not easy. The pitfalls were great and the hazards constant and the struggle was hard, yes, very hard indeed on both myself and my wife. It is my wish that on my death, my daughter, if she wishes, will hand the manuscript over to the Historical Committee of the RAOC so that it may be kept in the RAOC Museum.4 If it is decided that all or part could, with advantage, be published, then I should like any profits to be given to the Red Cross, to who owe so much and to the RAOC Aid Society, in equal portions.5

*****

Very early in 1940 I was commissioned in Hong Kong after what seemed an interminable length of time; it was an event for which I had planned and worked for over twenty years, but nevertheless the improvement in my status, if not in my finances, proved a considerable uplift. I was there at last; now I began to wonder how I should make out, how I would conduct myself, and how I would be accepted amongst those I had served. I need not have worried about the latter, everyone was most helpful and many gave me advice and guidance about my conduct and my new position. One brother officer had made for me a small leather covered stick, a symbol of my new rank, which I was to carry at all times when in uniform. It felt a bit like a Field Marshal’s baton and quite apart from keeping my hands out of my pockets became perhaps my most treasured possession until I had to exchange it for a rifle a couple of years later. It seemed like a magic wand and I came to regard it as such. I replaced it some years later but the new ones were never the same, the magic had gone.

My uniform was ‘made to measure’, my shirts were tailored, I now qualified for ‘Servant Allowance’, acquired a ‘Camp Kit’ and had my visiting cards printed. An Officer I now was; could I qualify as a gentleman as well? I left the first of my visiting cards at Flagstaff House, the home of my General and signed the visitor’s book. This would ensure that at some later date my wife and I would be invited to functions there. I thought very highly of this particular General; as a Conductor (Senior Warrant Officer Class I) I had been working closely with his staff and he had been my proposer when I joined the Hong Kong Jockey Club. (The Chief Justice was my seconder). Similarly, the leaving of cards and the signing of the visitor’s book at Government House, the residence of the Governor, followed. These matters of protocol and etiquette were viewed in a new light now I could appreciate their usefulness. There is a duty to those one likes, and dislikes, a responsibility to ‘keep up one’s position’ as a representative of His Majesty the King, to keep one’s subordinates ‘in good order and discipline’, to obey Orders and Directions given according to the Rules and Discipline of War, to act in the best interests of one’s country.6

My experience thus far had been in a minor executive role; but I was now about to embark into an administrative sphere as my first appointment on commission was on the staff of the GOC7 Shanghai as Deputy Assistant Director of Ordnance Services, Shanghai and Tientsin Area. I was on my own; there would be no one to ask for day-to-day guidance about my own particular job, only broad policy directions. I was ‘briefed’ by a Senior RAOC Officer in China Command HQ about my departmental duties. There would be no one to take over from as my predecessor had already left so I would be free to do things in my own way. There were two main points, however, on which I was to give most of my attention. They were: the running down of stocks in North China to realistic levels should the closing down of the installations in North China if and when the two infantry battalions there be taken away; and the removal of a large quantity of ammunition held in Tientsin and Peking which, due to reductions in the garrison, was not now required.8 There was, however, an urgent need for it elsewhere! I should examine these two situations on my arrival and consult with the GOC Shanghai and his staff on the agreed action to be taken. For the second time I disposed of my private furniture and effects in Hong Kong and, with my wife and two children, plus our Cantonese Amah, sailed for Shanghai in the SS Wo Sang, flagship of the local shipping line!9

The cabin, etc was palatial when compared to 2nd Class troopship accommodation and we dined at the Captain’s table! I studied with care the elaborate anti-piracy devices and grills, and the sickly looking guards who were to protect us, and in my cabin my own capacity to defend family and myself. Piracy on this run was a regular occurrence.10 Each ship carried large numbers of Chinese passengers with mountains of luggage and every conceivable kind of utensil and cooking pot and charcoal burner in the well deck, so it was easy for the ‘pirates’, at a given signal, to try to take the ship over. Most times they seemed to succeed but this time all was quiet and at last we sailed past the forts at Woosung and into the Whangpoo River. Shanghai: international city of teeming millions, of Concessions and settlements, poverty and plenty, vice and affluence, gangsters and godly men, of Russian princesses and opposing forces, and where ‘men from the sea foregather’. I had seen it before in 1927/28 when I came out with the Shanghai Defence Force, and again in 1939 when passing through en route for Japan, so to me it was not new.11

A suite of rooms had been booked for my family in the Palace Hotel, a corner site on the first floor with windows overlooking the Bund and Nanking Road – ‘Palace, the first place after you have stepped ashore and where you are sure to meet a friend’. It was full of American tourists, but very, very expensive for a newly commissioned Lieutenant. I reported to headquarters, left my cards at all the appropriate places and inspected my Shanghai Depot. This was housed in the upper floors of the racecourse stables in Mohawk Road, immediately behind the racecourse and the recreation ground where the Seaforth Highlanders were stationed. They provided the guard on my depot. Not much in the way of stores, thank goodness, chiefly warlike items. No ammunition or barrack stores, the two Battalions and Barrack Officers took care of them. Not much of a task evacuating Mohawk Road if and when the time came. The small depot was well run and the accounts quite satisfactory. The single members of staff lived in depot premises but ate with the Seaforths. Demands for stores, which we could not meet, were forwarded to Hong Kong for direct supply. HQ would try to find me a house. Quite good, I mused, on my way back to the Palace Hotel. I had hardly got into the hotel when all hell was let loose outside and as I looked down from my first floor vantage point I witnessed my first street gun battle between two opposing forces. The streets cleared as if by magic as the antagonists fought it out from behind pillars; it was a vicious affair while it lasted but it was quickly brought to a halt by the Shanghai Municipal Police who arrived with machine guns blazing, cutting down the protagonists from either side. They heaved the dead bodies into the back of a truck and within seconds all was back to normal, just as if nothing had happened. This eye opener was an abject lesson for me as it became the pattern of daily life in the big city and made me even more concerned about the safety of my family. A bad start, too, for my wife, but she never complained, just gathered her offspring around her. Our Amah12 was upset and determined to leave for the land of her ancestors at the earliest moment!13 Having made my acquaintance with the Commanding Officer [CO] and Officers of the Seaforth Highlanders, who made me an honorary member of their Mess, I proceeded next day to lunch with the Commanding Officer of the East Surrey Regiment in their Mess where again I was invited to become an honorary member. As I had no Mess of my own, these gestures were much appreciated and I was at home with both units. The East Surreys were manning the British sector of the perimeter and doing one hell of a job when in the company of their CO I visited them on the banks of Soochow Creek.14 The adjoining sector was manned by Italians with whom, at that time, February/March 1940, we were at war. How strange it seemed that two countries at war with each other should be defending the same perimeter, side by side, contradictions I was soon to become accustomed to. Germans, too, there were in plenty in the settlement but each nationality, though at war, kept strictly apart. You did not partner them on the tennis courts, or drink together at the bars, but just maintained a rigid and distant politeness, observed and respected by both sides. What an Alice in Wonderland set up! I wonder what Gilbert & Sullivan would have made of it?15

It had been suggested at Shanghai HQ that I arrange my first visit to North China as early as possible in the company of the CO of the East Surreys who had one company stationed in Tientsin16 and a detachment at Peking17. It would help me get to know the people I would need to rely on and I would get to know the ropes when dealing with the Japanese and other unfriendly, and friendly, nationals in the easiest possible way. I should give my first priority to getting the ammunition out, if possible – it was needed urgently in Singapore. In this connection I should first make contact with the Political Officer at Tientsin who would give me advice, guidance and help as to who was privy to what was required. At this stage I was told that the French had in their Concession a quantity of ammunition which they too wanted to get out of Tientsin to bolster up their stocks in Indo-China. This introduced a new dimension to the problem. The Japanese who controlled everything that went in and out of both Concessions and who were in occupation of the surrounding territory were the main obstacle. They made constant searches, confiscating anything they did not like.

A passage was booked for both of us on the next ship going to North China. It was fortuitous that this should be a very small tramp steamer which plied regularly between the ports of North China and was well known along the China costs; her officers and crew had long experience of the east and of the ways of both Chinese and Japanese. We made our way slowly up the coast, the ship being completely blacked out, calling at Tsingtao,18 which had been a German Concession until the World War and then Chefoo,19 where we took on board a large quantity of prawns in barrels. I have never seen such large prawns before or since; they were reputed to live on the dead bodies washed down by the rivers to the many sand banks but they tasted wonderful and we feasted on them for most meals. I had another look at Wei Hai Wei,20 used as a Naval Anchorage and torpedo testing area, where I had spent some weeks recuperating in 1928, with its wonderful silver sand beaches. We disembarked at Taku21 to continue our journey by train. The ship, the Lee Sang, would be unloading part of her cargo there to lighten the ship and then make it possible to go up the Hai Ho River as far as Tientsin. It was only a short journey but we were watched constantly and questioned as to why we were going to Tientsin22 and what our business there was. Would we be calling at Japanese HQ? We had plenty of evasive answers to give. Quite obviously, we would be watched, right throughout our journey. I had met this kind of thing before, when I went for a holiday to Japan in 1939. From the time we entered the Oriental Hotel in Kobe, wherever we went and until the time we left, our personal spy was in attendance. It is quite a game! But serious too, as one of my friends had found out in Japan when he took a photo of some lovely flowering shrubs and was promptly arrested and then found out they were camouflage for a gun!23

On arrival at Tientsin Railway Station we were ‘taken over’ by our representatives there, the OC24 East Surrey Regiment went to their Officer’s Mess while I went to my hotel, each going his separate way. The Court Hotel was an extremely Victorian establishment and lived up to its name and reputation; it was the kind of place with a long history where government officials could feel secure and where their baggage would most likely not be rifled while they slept or were away at breakfast; where snipe, quail and woodcock regularly appeared on the menu and bridge was played after dinner. I imagine it had not changed since before the Boxer Rebellion!25 It was the scene of much previous glory! I settled in quickly and was whisked off (by car) to inspect the Ordnance Depot, Tientsin. This was a small but efficient Tun Depot, part of an old barracks with an extensive parade ground and an apparatus for disposing of unwanted explosives in minute quantity. There was a small staff headed by a Sub-Conductor and one Ammunition Specialist; they were obviously pleased to see an officer of their own corps as I gathered they had for a long time felt ‘out on a limb’. I enjoyed talking to each individual, listening to their problems (all were minor) and gave them some hope that they were not forgotten even though there was a war going on at the other side of the world. They were all doing a really good job and it was obvious they had gone to great pains to impress me. I had confidence in all of them as did the units they served. I inspected the whole of the depot most carefully and in particular the magazine area, which housed quite a lot of serviceable small arm ammunition.