8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

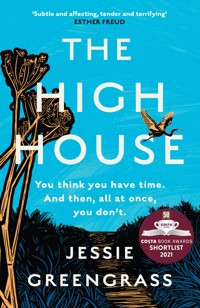

'SUFFUSED WITH JOY' Guardian, 'PROPHETIC' Daily Mail, 'BEAUTIFUL' Scotsman, 'IMMERSIVE' IMAGE Perched on a hill above a village by the sea, the high house has a mill, a vegetable garden and a barn full of supplies. Caro and her younger half-brother, Pauly, arrive there one day to find it cared for by Grandy and his granddaughter, Sally. Not quite a family, they learn to live together, and care for one another. But there are limits even to what the ailing Grandy knows about how to survive, and, if the storm comes, it might not be enough. 'Deeply moving … so grounded in reality and the ordinariness of the lives of this disparate group, that I had to read parts of it through my fingers' Good Housekeeping Books of the Year

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 288

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Who sang, sea takes, brawn brine, bone grit. Keener the kittiwake.

—Basil Bunting,Briggflatts

Contents

The High House

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Acknowledgements

The High House

Sally

In the morning, I wake earlier than the others. I climb out of bed in my jumper and my socks and I pull on my dressing gown, and after it my leggings and my boots. I go downstairs, and it is cold and dark and very quiet. My boots are beginning to go at the heels, now, but I am trying to get this last winter out of them. My jumper and my leggings are frayed at the cuffs, and my dressing gown is an old blanket with holes cut out for the arms, because dressing gowns are a thing that Francesca didn’t think of – and although, between the three of us, we have a reasonable spread of skills, none of us can sew.

In the kitchen, I check the fire in the range, put fresh wood on the embers and open up the vent until it burns. I pour the last of yesterday’s well water into the kettle and set it to boil, put dried mint leaves in a mug, make tea. I would have had coffee, once. I think this every morning. I think it, and then I think I can still catch the taste of it, but it’s been so long that it could be the taste of anything I am remembering. Milk. Mustard. Ham. They all bring the same flood of saliva into my mouth and the same sad twist into my chest.

Yesterday it rained and I didn’t do my coat up properly. Water got in at the collar and I spent the whole day damp, but today I can feel the chill of empty skies and so, I think, it will be clear. Outside, beyond the window, past the orchard, the sky is still full dark, but soon it will start to pale. I open the doors a crack and the air is fresh and cold, and it smells of salt. It will be an hour or more before the others are up. Caro sleeps badly, and often goes into Pauly’s room in the night, to lie on the mattress he keeps for her on the floor beside his bed. When he wakes, he will stay still so as not to disturb her. It is his own kind of peace, he says, to lie warm under the blankets in the dark with nothing to do. We take these small luxuries where we can, especially in winter.

You would think that with so much space – with the house and the garden, with the copse and the heath, the dunes and the beach, and only ourselves – it would be easy to be alone, but we are a knot. We cling. Each of us knows, at all times, where the others are, in the same way that we always know what time it is, telling it from some combination of light and shadow and our bones, so that it is only now, when it’s early, when Pauly and Caro are upstairs, asleep or still, and things have not quite begun, that I can feel as though I am by myself. I step out through the doors into the garden and, around me, silence spreads. I feel its emptiness. The air begins to lighten. Each breath hangs. I go down through the orchard, through the arch in the hedge, along the path and past the tide pool to where the river spreads, freed now of its cuts and embankments, its holdings and constraints, to make its own slow way into the sea—

Spring is coming. Its mnemonic is in the earth and in the branches, in the greening of the buds, the new spears poking among the dead reeds – and even while the cold still creeps into my clothes, I think of the warmth that will come to chase it, soon. The grass is wet around my ankles. The air is still. From here I can see what is left of Grandy’s cottage, and below it the half-gone pub, the village green. The rusting arc of the swing frame rises like a monument. Each year, between water and neglect, less and less of the village remains. Grass grows in tufts from walls. Silt covers gardens. Crabs run across the broken cobbles of the road. I listen to the pip, pip of the oystercatchers and a solitary curlew’s call, and it seems strange to say it, but I am not unhappy. Dawn comes. I turn around and walk back the way that I have come, up the path, away from the river – towards the high house, which is my home.

1

Caro

The high house belonged to Francesca’s uncle, first, but the uncle died not long after she and my father met. He had no children of his own, and so he left the house to Francesca, and the parcel of land that went with it, the orchard and the vegetable garden, the tide pool, the mill. For a long time, the house had been neglected. When I first came here, for summer holidays with Francesca and with father, damp patches spread around the corners of the downstairs rooms. Tiles were missing from the roof. I remember the chill the house had, even in summer, and the way the wind swooped down the chimneys at night. The orchard, outside the kitchen doors, was overgrown, and, beyond it, past the unruly beech hedge with its branch-obstructed arch, the tide pool was choked with reeds. Twice in every twenty-four hours water would flow into the pool, but the sluice gate was long shattered and so, where once the water would have been held to turn the wheel, it only trickled out again as soon as the tide began to ebb. The mill had half-fallen into the mud. The wheel was rotten. It would have been used to grind wheat, when it was built – and now it turns again and powers our generator, which gives us light in winter for as long as we have the bulbs, and runs the fridge in summer. Now, the orchard is carefully pruned. We do the apples in winter and the plums at midsummer, like Grandy taught us, carefully cleaning and sharpening the pruning saw, keeping the secateurs on string round our necks because they are so easy to lose. Now, the hedge is clipped. In the vegetable garden, things grow in rows. There is a greenhouse with all its glass intact. This is what we do, now. We dig and we weed. We plant. We store seed, and we watch the weather carefully for signs of frost. Now, there are hens in the hen coop, although in winter they live mainly in the scullery. We have fields, too, which we have claimed because there is no one else to want them. But when I was a child the orchard and the gardens were overgrown. The coop was empty. The house was dusty and unloved.

i

The high house isn’t high, really, but only higher than the land around it, so that when it was first built, before the river had been banked and the cuts made to drain the land, when the rain was heavy and the tide was up and the water spread where it wanted, the house would have been an island, almost, with only the westerly part of its land unflooded, a causeway above the waterline joining the house to the heath. And now at times it is almost an island again.

ii

In those first years, before Pauly was born, after Francesca came to live with me and father, we used to come here for our summer holiday, the three of us spreading out through the rooms of the high house, all into our different places. We were very separate. Francesca worked, up in one of the top rooms, one we use now to store apples, spread in lines across the floorboards, and potatoes in sacks. I roamed the garden, building dens in the honeysuckle which crept across the ruins of the walled garden, decorating my hair with goosegrass, making fairy umbrellas out of coltsfoot leaves. Father stayed in the kitchen. He sat in the old armchair by the French doors, reading, or he stood at the kitchen counter, chopping vegetables to make lunch. When I was tired of being by myself, I came in from the garden and trailed after him, nagging to be taken somewhere.

—Where, though, Caro?

—The pool, please.

I loved the tide pool, then. Even now, when we are so reliant on it, I regret the loss of its wildness, the way it was before Francesca restored the mill, when reeds grew down close around its edges and small creatures rustled in and out of them, going about their secret business. I loved how still it was, the way the water rose and fell, creeping rippleless up the banks, the way its surface shone when sunlight caught it – but father was afraid of me falling in, or getting caught in the mud, so I wasn’t allowed to go near it by myself.

—Oh, all right,

he said, and went to find his jacket and his boots. I waited for him in the orchard, joggling from one foot to the other, until at last he came out to me and we walked through the hedge, down the path which slopes through a sort of meadow, to where the pool is. There, he sat and watched as I swished through the grasses, taking off my shoes to feel the mud suck around my feet, searching for treasures – stones or feathers or once, miraculously, a nest of eggs, each one cracked open where its chick had hatched but otherwise intact, pale blue, speckled, near weightless in the palm of my hand. He watched me until the shadows lengthened to cover the pool entirely, until I started to shiver and yawn, and then he said,

—Home time, Caro. Chop chop.

—I don’t want to put my shoes back on.

—Leave them off, then.

I gave him my shoes to carry, and held his hand, and together we walked back to the high house, where Francesca, alone in her upstairs room, kept working.

iii

On other afternoons, father and I went to the beach to dig holes or to throw stones into the sea, the hand-sized flints that stretched like strange eggs along the tideline. Sometimes he let me bury his feet in the sand, or if it was hot enough then he took me into the sea to swim, holding me under the armpits while I splashed. When I thought I felt something touch my foot I screamed, and he laughed, and I clung to him, my arms round his neck and my legs round his waist. I wasn’t afraid of the water, then – or if I was then it was a pleasant kind of fear, the sort which sends you yelping with laughter back up the beach when a big wave comes, before you turn and run to chase it out. It was often hot, in July and August when I was a child, although not in the way that it became later, when summers lasted half the year and every day was a white sun in a pale sky. There were lots of holiday lets in the village, and by late morning the section of the beach closest to it would be laid out with people, row after row of them on their backs, or sitting with their children round them, buckets and spades scattered about, and the remnants of picnics, bottles of sun cream, sun hats, spare clothes. Francesca, back in the house, would say,

—How can they stand to enjoy it, this weather?

She didn’t have the habit that the rest of us were learning of having our minds in two places at once, of seeing two futures – that ordinary one of summer holidays and new school terms, of Christmases and birthdays and bank accounts in an endless, uneventful round, and the other one, the long and empty one we spoke about in hypotheticals, or didn’t speak about at all.

—They act as though it’s a myth to frighten them,

Francesca said,

—instead of the imminently coming end of our fucking planet,

and I knew that when she said ‘they’ she meant father, too, and me.

iv

This was when it was still the beginning of things, when we were still uncertain, and it was still possible to believe that nothing whatever was wrong, bar an unusual run of hot Julys and January storms. All summer I ran, half-naked, through the fine days, and when the weather broke, bringing rains so heavy that the water fell in long ropes through the air, I sat inside the high house and watched it from the window, marvelling at the quantity of it and the force, how it scoured what it touched, washing crisp packets out of hedges, flattening shrubs, cleaning dust – and then, next morning, it would be hot again, but the air would be filled with steam; and the sea, where the river ran into it, stained with mud.

v

We went to the high house at Christmas, too, when some years snow lay on the beach and ice washed in grey sheets down the river, and other years the grass still grew and the leaves had barely turned on their branches. We ate mushroom risotto and then poached pears, and sat by the fire which father had lit, and we opened our presents. No matter what we did, the house seemed to stay empty, with all the doors and windows shut against the cold and so many of the rooms dark, and I tried to make my voice fill up the house while father and Francesca sat on the sofa and read, but there was only one of me and I couldn’t make enough noise alone. When the time came to go back to our home in the city it was a relief, because there our lives had formed around us. At home, I knew how to be lonely without it showing. I knew how to occupy myself in my own way, in my own world, which was separate from father or from Francesca – which was private. At home, I knew how to be complete. And then, after a few years, Francesca let the high house out. A young artist lived there for a while. Francesca didn’t like her work, which she thought too comfortable,

—As though,

she said,

—there was nothing important to be thought about.

When the artist left, a group of students from a nearby agricultural college moved in, and Francesca let them pay a nominal rent in exchange for renovating the garden.

vi

All that was before Pauly was born, when there were still only three of us. Francesca was not my mother. She loved me but there was no structure to it. I loved her but I was unsure of her. We rarely touched. Father loved us both but serially – first one, and then the other. He couldn’t love us both at once because we needed such different things from him. As a three, we were not unhappy, exactly, but we weren’t happy, either – and although sometimes it seems to me, looking back, that my childhood ended when Pauly came, I can’t say that I regret it. It was too quiet, then, and I was too often alone. It is hard to be a child in isolation. You take on adulthood like a stain.

vii

I was fourteen the day Francesca brought Pauly home from the hospital. Father and I spent the morning cleaning the house, polishing and sweeping and dusting, until every room smelled of beeswax and vinegar. There was a bunch of sunflowers on the table in the hall, stood up in a water jug.

—She’ll say we shouldn’t have bought cut flowers,

I said, but father replied that just this once she’d like them anyway, which I thought, privately, seemed unlikely. Francesca had been gone a week. The birth had been difficult, father told me, when he came back from the hospital in the middle of the night for a change of clothes. The baby had been positioned awkwardly and for a long time its shoulders had been stuck trying to get free of Francesca’s pelvis, and also there had been a loop of umbilical cord round its neck which all the struggle had pulled tighter and tighter so that when at last the baby had been got free, tugged out by a pair of forceps clamped round its skull, it had been blue-grey and limp, and the doctors had taken it straight off, before Francesca and father had even heard it cry, to another part of the hospital to be wrapped in a cooling blanket in case its brain had been damaged.

—The baby is a boy,

father said,

—and we have called him Paul.

Father looked worn out. I made him cups of tea and cooked him pasta with tomato sauce whenever he came home, and I said that of course things would be fine – but to myself I thought that perhaps they would not be fine. I thought of babies in neonatal units, the photos of them I had seen in charity Christmas campaigns or on the news, their tiny bodies old-looking and plugged with wires, barely human, skin like tissue paper spread over bird bones. I thought of the baby, Paul, my half-brother, swaddled in an incubator, and I tried to think of Francesca sat beside him, waiting – but it was impossible to imagine her in such a place. I could not think of her at the mercy of doctors, reaching for a baby that she was not allowed to touch. I could not think of her afraid, but only of her saying to me, when I’d once wanted to know why I wasn’t allowed to drink juice from a carton,

—We all have to make sacrifices, Caroline. That is how things are.

No one but Francesca has ever called me Caroline.

viii

When we had finished cleaning, father and I ate lunch, and then we washed up, put everything away, swept up the crumbs. Scrubbed out all signs of ourselves. Father asked if I wanted to go with him to the hospital but I said no, because I was afraid, both of the baby and his birth bruises, and of Francesca, of what had happened to her and of its consequences – that she would either be herself or would be not herself, changed, a strange infant in her arms. Father kissed me, and then he put on his coat and went out to the car. I stood on the doorstep and watched him drive away, and, when he was quite gone, I closed the door behind him and began to wait. I went into the front room, first, where the cushions on the sofa were all undented and every book was slotted into its right place on the shelves. After that I went into the kitchen, where there were no mugs waiting to be washed, and into the bathroom, where the towel hung clean and folded and the soap sat square in its dish. In the room that Francesca shared with father, fresh sheets were tucked neatly beneath the mattress on the bed. The washing basket was empty, its usual tangle of jumpers and tights unpicked, washed and put away. Next door, the baby’s room waited, perfect, for a baby. Even my own room was clean, its carpet denuded of books and clothes, its bed made and everything swept, orderly and unfamiliar. I sat at the bottom of the stairs, watching the door, waiting at the centre of all the messless emptiness of our house, and I might have felt unwanted, then. I might have felt that I, too, had been smoothed out, as though father and Francesca had given me up to start again – but really I only felt that I was poised, en pointe. An end had come, but not a beginning, yet – and then, at last, there was the sound of the car, the key in the door. Father stood aside to let them in, Francesca with the baby in her arms, and it was as though not just my brother but both of them were newly born, their fragile skin pinked by first exposure to the sun. I stood in the hallway, feeling the whole world still about me, as Francesca held the baby out to me and said,

—Look, Caroline! This is Pauly—

and I reached out and took him from her, and time began again.

ix

Sometimes, when Francesca went for a shower, she would give me Pauly to hold, and I would watch him, his tiny curving body nestled into the crook of my elbow, his arms and legs waving gently like ropes of seaweed in an underwater current. He felt as though he were a part of me, then, and when he looked at me and I looked back, our matching eyes held wide, I thought I knew him and he knew me too – until his mouth began to seek, head turning side to side, and his coughing sobs turned into cries and brought Francesca running back.

x

Each morning, father took up residence at the toaster.

—What today, then?

—Two slices, please.

I poured coffee from the pot, one for each of us, and one for Francesca, who came downstairs in her dressing gown, her eyes puffy and face creased, saying,

—Don’t ask me how the night was. I feel like I could eat the bloody loaf.

She put the baby in his bouncy chair and sat down next to it, joggling him with her foot so that he tick-ticked up and down, waving his hands in front of his face. In the background, the radio: …fears for the eastern seaboard of the United States as storms—

—Turn that thing off, would you?

father called to me and Francesca didn’t stop me, although she frowned, said,

—Turning it off won’t make it go away—

We poured milk, passed jam. Father took his lunch out of the fridge and packed it in his bag, searched for his wallet and his keys, got ready to leave for his job at the university.

—Another day of students. When will it end—

I peeled an orange and offered it to Francesca, who took it from me, pulled it into segments and ate them, one by one, while Pauly in his chair watched her and made a sort of humming sound.

—Thank you, Caroline.

We had been reconfigured. As a three we were unbalanced, but the baby’s weight had evened out the scales. It seemed, at times, as though it were a magic trick done skilfully, so swift and smooth, and I was afraid in case, were I to learn the way that happiness was palmed, the trick would cease to work. Father, buttoning up his coat, said,

—What’s today then?

—Double maths,

I told him,

—and French. I hate French.

Francesca picked Pauly up,

—Come on, piglet,

she said to him,

—let’s get you into some clean clothes—

and she carried him away from us, back up the stairs, into the soft confines of that cocoon which his room had become.

xi

When I got home from school they were together in father and Francesca’s bed, Pauly having his nap and Francesca working, a book in one hand and her notebook open beside her. Pauly, his face pink, his breath even, was draped across her lap and I sat with them, doing my homework on the floor at the end of the bed until Pauly woke, and then Francesca and I played games with him, stacking towers of wooden blocks for him to knock into a heap, pushing toy cars so that their wheels rattled across the floorboards. He liked to be turned upside down, squealing as we took it in turns to dangle him backwards from our laps. I dropped a rubber ball and he watched it bounce down towards stillness. The phone rang. Francesca answered it, and while I sat on the floor opposite Pauly, trying to teach him to clap, I heard her say,

—They think this baby is an admission of defeat,

and then,

—They think it means that I no longer care. Or that I don’t believe in what I say—

but watching her I thought that it was not defeat at all. Rather, it was a kind of furious defiance that had led her to have a child, despite all she believed about the future – a kind of pact with the world that, having increased her stake in it, she should try to protect what she had found to love.

It is so hard to remember, now, what it felt like to live in that space between two futures, fitting our whole lives into the gap between fear and certainty – but I think that perhaps it was most like those dreams in which one struggles to wake but can’t, so that over and over again one slips back against the mattress, lets the duvet fall and shuts one’s eyes. There is a kind of organic mercy, grown deep inside us, which makes it so much easier to care about small, close things, else how could we live? As I grew up, crisis slid from distant threat to imminent probability and we tuned it out like static, we adjusted to each emergent normality and we did what we had always done – the commutes and holidays, the Friday big shops, day trips to the countryside, afternoons in the park. We did these things not out of ignorance, nor through thoughtlessness, but only because there seemed nothing else to do – and we did them as well because they were a kind of fine-grained incantation, made in flesh and time. The unexalted, tedious familiarity of our daily lives would keep us safe, we thought, and even Francesca, who saw it all so clearly – even she who would not let herself be gulled by hope – stood by the open fridge at five o’clock in the afternoon and swore because there was nothing to give the baby for his tea. We fed him fish fingers from the freezer. Father came home. Pauly had his bath, splashed the water with his fists, sucked the flannel, then cried when it was taken away to wipe him. Afterwards, consoled, he was wrapped in a towel to be dried. I kissed him on his damp and rumpled hair.

—Goodnight, Pauly.

Francesca carried him off to bed. Father made dinner and opened a bottle of wine so that a glass was poured, ready, when she came back down, blinking in the light.

—He’s asleep at last, thank Christ—

And all the while, outside, the thing that only she could look at straight: the early springs and too-long summers, the sudden, unpredictable winters that came from nowhere and brought floods or ice or wind, or didn’t come, so that there was only day after day of sticky dampness and the leaves rotting on the trees and the birds still singing in December, nesting, until the snow came at last and, having overlooked migration, they froze on the branches, and they died.

xii

Francesca, on my laptop screen, was making a speech. Pauly, not yet six months old, was asleep in a sling on her front, his head tucked in beneath her chin, his legs dangling around her waist. She said: We must recognise that we are being given a final warning–because if we fail to do so, if we fail to act, the consequences will surpass anything we have previously seen, and we will have missed our chance—

They seemed so much a pair, then, Francesca and Pauly, and as he began to take shape, his personhood unfurling like new green leaves, he grew towards her, reaching out to catch and climb. It was a joy, I found, to watch them. I loved to pick Pauly up when Francesca left the room to fetch something, or to speak on the phone, and to whisper in his ear as he began to fret, Don’t worry, Pauly, she’s coming back—

It seemed miraculous that this tiny almost-person, whose needs were so immediate, whose sense of loss at his mother’s absence was so overwhelming, might be so easily restored when Francesca came back and lifted him up onto her hip again. Then his tears would stop at once and he would glare out at the world reproachfully, knotting his fists into her shirt – but nothing lasts. At night the world seems full of edges. The moon, shining through the window, shows up the corners and the breaks. Pauly and Sal think that it is fear which wakes me, which gets me out of bed to go into the garden, to walk beside the river in the dark, but it isn’t fear, or not only. It would be so easy, in this green place, to think we had won through – that it was an act of skill or of prescience on our part which had brought us here, in place of all the others who it might have been instead. It wasn’t skill. It was only the opportunity Francesca gave to us, and the choice to use it on ourselves. In Pauly’s room, before I fall asleep, I stare at his young man’s face and try to remember what he looked like as a child, but I have forgotten. I pull the blankets over me and I match my breath to his until, at last, I fall asleep.

xiii

One afternoon, while Pauly had his nap, father and Francesca and I sat on the living-room sofa and watched an island in the mid-Pacific sink. We saw the storm arrive, the cameras picking up the rain, the swelling wind. We saw doors torn from hinges, palm trees bend and give. We watched as an ordinary piazza in a far-off seaside town came apart, its street signs snapped, lamp posts buckled, the café on the corner split open like an egg. Father said,

—At least they knew it was coming.

On the screen, a whole car flew past.

—I mean, everyone had got out already.

Francesca, face taut with fury, stood up and, going into the corner of the room, put both hands against the walls.

—That,

she said, her back to us,

—is very far from the point. And anyway,

she went on, speaking with such fierceness that I thought her words might drill holes through the lath and plaster to let her out of the room, out of our lives,

—there are always some who stay. Why not? Where else can they go? A fucking refugee camp? While the rest of the world argues about who should take responsibility for them? Yesterday they had lives, and now they’re just faces in a bloody queue.

—I know,

father said,

—I’m sorry.

—Everybody’s fucking sorry—

Next morning, after the storm had moved away, we turned on the television again and saw satellite pictures of the place where the island had been, and where there was nothing now but bare earth and a patch of ocean scummy with debris. The people who had lived there were now in temporary shelters, we were told, on the nearest major landmass, a thousand miles away from where, a week earlier, they had been at home. It was unclear how many had chosen to stay.

In the afternoon, Francesca put her laptop on the kitchen table while she made flapjacks and, sitting with my feet propped up on Pauly’s highchair, eating raisins she had spilled, I watched news footage of families hunched under tarpaulins. They looked resigned, as though they already understood what they had become a part of, and I tried to stop myself from crying because I was ashamed of my tears, which were neither compassionate, nor empathic, nor kind, but came because I was afraid, very suddenly and directly, for myself.

xiv

It was evening, and Francesca was packing a bag. Father followed her about as she went from room to room, collecting jumpers, chargers, a toothbrush.

—What about us,

he said.

—What about Pauly?

—Paul will be fine.

Francesca slipped her passport into the top pocket of her suitcase. Father said,

—He needs you.

—He has you,

Francesca answered, and she went into her study, and shut the door behind her.

Later, waiting for a taxi, kneeling down to kiss Pauly on his forehead, Francesca said,

—I’m sorry.

It wasn’t clear which of the three of us she was talking to.

—If I can help at all – if there’s anything I can do – then I have to go.

—Yes,

said father,

—of course, you do.

—I’ll be back in a few days. A week, maybe. I have to go. I have to see it for myself. There have to be witnesses.

—Yes,

said father, again.

—We can’t just turn our backs.

That night, Pauly wouldn’t sleep. He stood at his bedroom door, his face wet with tears and sweat, and howled as though he were in pain. I tried to pick him up, to comfort him, but he writhed and kicked his heels against my legs until I let him go, and so instead I sat next to him, on the brightly coloured carpet, and I whispered to him and kept on whispering,

—It’s okay, Pauly, it’s okay. It will be okay. I love you. It’s okay—

but it was nearly midnight before at last he fell asleep, exhausted, half in and half out of the doorway. I watched him until I was sure he wouldn’t wake, and then I carried him to bed. I put on my pyjamas, brushed my teeth, fetched a glass of water, and then, for comfort – his, or mine – I climbed in next to him and, with his small feet pressed against my stomach, I slept, too.

xv

In a newspaper column Francesca wrote:

As scientists we are used to remaining in one place. We tell ourselves that it is our job only to present the evidence–but such neutrality has become a fantasy. The time for it is past.

Every day father went to the university, taught classes, ran seminars. In the evening he came home and marked papers, pursuing his own research in the gaps – and so it was hard not to see Francesca’s words as personally directed, a facet of their relationship played out in public. Even then, I knew enough to wince, but there was Pauly to be looked after – and, anyway, perhaps what she had written was less an attack than it was an apology, that she should place the hypothetical, general needs of a population above the real and specific ones of her family. And, anyway, didn’t it turn out that she was right.