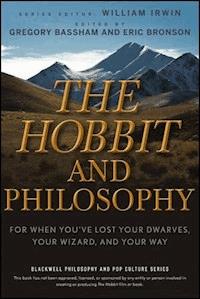

16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

A philosophical exploration of J.R.R. Tolkien's beloved classic--just in time for the December 2012 release of Peter Jackson's new film adaptation, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit is one of the best-loved fantasy books of all time and the enchanting "prequel" to The Lord of the Rings. With the help of some of history's great philosophers, this book ponders a host of deep questions raised in this timeless tale, such as: Are adventures simply "nasty, disturbing, uncomfortable things" that "make you late for dinner," or are they exciting and potentially life-changing events? What duties do friends have to one another? Should mercy be extended even to those who deserve to die? * Gives you new insights into The Hobbit's central characters, including Bilbo Baggins, Gandalf, Gollum, and Thorin and their exploits, from the Shire through Mirkwood to the Lonely Mountain * Explores key questions about The Hobbit's story and themes, including: Was the Arkenstone really Bilbo's to give? How should Smaug's treasure have been distributed? Did Thorin leave his "beautiful golden harp" at Bag-End when he headed out into the Wild? (If so, how much could we get for that on eBay?) * Draws on the insights of some of the world's deepest thinkers, from Confucius, Plato, and Aristotle to Immanuel Kant, William Blake, and contemporary American philosopher Thomas Nagel From the happy halls of Elrond's Last Homely House to Gollum's "slimy island of rock," this is a must read for longtime Tolkien fans as well as those discovering Bilbo Baggins and his adventures "there and back again" for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments: Thag You Very Buchx

Introduction: Never Laugh at Live Philosophers

Part One: Discover Your Inner Took

Chapter 1: The Adventurous Hobbit

A Hobbit’s Progress

Bilbo’s Growth in Wisdom

Bilbo’s Growth in Virtue

Chapter 2: “The Road Goes Ever On and On”: A Hobbit’s Tao

The Fellowship of the Tao

Another Way of Thinking of the Way: Seven Taoist Masters

Gold-Is-Heavy

Empty-Mind

Chapter 3: Big Hairy Feet: A Hobbit’s Guide to Enlightenment

“Not So Hasty”

Walk for a Cure

Walk This Way

Mind Your Steps

Chapter 4: Bilbo Baggins: The Cosmopolitan Hobbit

Hobbits in Kansas

An Ancient New Way to Live in the World

Dwarves as the “Other”

Everyone Wants a Mithril Coat

Learning from Other Cultures

Can We Really Live Like Bilbo?

Part Two: The Good, The Bad, and The Slimy

Chapter 5: The Glory of Bilbo Baggins

Glory in the West and Middle-Earth

Beauty First! Then Glory!

The Making and Unmaking of Hobbits

Chapter 6: Pride and Humility in The Hobbit

Virtue in Middle-Earth

Proud to Be a Hobbit

Humble Pie and Soul Food

Humble Heroes

Chapter 7: “My Precious”: Tolkien on the Perils of Possessiveness

The Social Costs of Greed

The Personal Costs of Greed

Queer Lodgings

Chapter 8: Tolkien’s Just War

War! Huh! What Is It Good For?

The Battle of Five Armies

Was Tolkien Really a Just-War Theorist?

Chapter 9: “Pretty Fair Nonsense”: Art and Beauty in The Hobbit

Tolkien and the Art for Art’s Sake Movement

“Just for the Fun of It”

“They Too May Perceive the Beauty of Eä”

“The Love of Beautiful Things”

Chapter 10: Hobbitus Ludens: Why Hobbits Like to Play and Why We Should, Too

Football, Golf, and Other Games Hobbits Play

What Play Is Not

The Goodness of Play

Adventurous Play: Bilbo’s Education

Playing with Fire: Gandalf and the Goblins

Playing by the Rules: Riddles and Ethics

Recreation and Subcreation

The Limits of Play

The Professor at Play

Part Three: Riddles and Rings

Chapter 11: “The Lord of Magic and Machines”: Tolkien on Magic and Technology

The Will to Magic

Tolkien’s Vision of Nature and the Modern World

Chapter 12: Inside The Hobbit: Bilbo Baggins and the Paradox of Fiction

Paradoxes in the Dark

Confusticate and Bebother!

Quasi-Bewutherment

Out of the Frying Pan and into the Fire?

Living with Bewutherment

Chapter 13: Philosophy in the Dark: The Hobbit and Hermeneutics

The Rules of Riddles

Bilbo’s End: Intentionalism

Riddle Me This, Professor Hirsch

Gollum and Gadamer

What’s in Bilbo’s Pocketses?

Out of the Frying Pan

Part Four: Being There and Back Again

Chapter 14: Some Hobbits Have All the Luck

Aristotle and the Riddle of Luck

Leaf by Nagel

The Good, the Bad, and the Lucky

Better to Be Lucky and Good

Chapter 15: The Consolation of Bilbo: Providence and Free Will in Middle-Earth

What Has It Got in Its Pocketses?

The Problem of Divine Foreknowledge

Freedom and the Music

Tolkien’s Boethian Solution

Chapter 16: Out of the Frying Pan: Courage and Decision Making in Wilderland

Riddles, Dilemmas, and Luck, Oh My!

By the Light of the Trolls: Expected Utility Theory

Playing Hide-and-Seek with the Wood-Elves: Conditional Probability

To Boldly Go—but Not Too Boldly

Chapter 17: There and Back Again: A Song of Innocence and Experience

There but Not Quite Back Again

Some Who Wander Are Lost, or Growing Up Is Hard to Do

Striving to Be Original, Again and Again

Back Again to the Beginning

Contributors: Our Most Excellent and Audacious Contributors

Index: The Moon Letters

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Series Editor: William Irwin

Copyright © 2012 by John Wiley & Sons. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

The Hobbit and philosophy : for when you’ve lost your dwarves, your wizard, and your way / edited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson.

pages cm.—(The Blackwell philosophy and pop culture series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-40514-7 (pbk.); ISBN 978-1-118-22019-1 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-23389-4 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-25855-2 (ebk)

1. Tolkien, J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel), 1892-1973. Hobbit. 2. Tolkien, J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel), 1892-1973—Philosophy. 3. Fantasy fiction, English—History and criticism. 4. Middle Earth (Imaginary place) 5. Philosophy in literature. I. Bassham, Gregory, 1959- editor of compilation. II. Bronson, Eric, 1971- editor of compilation.

PR6039.O32H6365 2012

823′.912—dc23

2012007299

For our halflings, Dylan, Asher, and Max

A vanimar, nai tielyar nauvar laiquë arë laurië

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thag You Very Buch

In putting together this book, we have been blessed by good luck far exceeding the usual allowance. Our warm appreciation to our long-suffering contributors for their patience in bearing with two grim-voiced and grim-faced editors; to Connie Santisteban, Hope Breeman, and the other good folks at Wiley who shepherded the book to publication; and to copyeditor Judith Antonelli for covering our tracks through the deep, dark forest. As with most of our previous collaborations, this fellowship began with a beer- and pipeweed-fueled council with series editor, Bill Irwin. We are especially grateful to Bill for encouraging our adventure in coediting not one, but two, popular culture books on Tolkien and philosophy. Two large flagons of thanks go out to Madeline and Lyndsey Karp and Greg’s students in his Faith, Fantasy, and Philosophy course at King’s College.

But our greatest debt is to our fairy wives, Aryn and Mia, and to our own hobbits—Dylan, Asher, and Max, to whom this book is dedicated. There are few earthly joys that can match reading Tolkien’s tales of Middle-earth to one’s children and seeing that spark kindle from mind to mind, like the beacons of Gondor.

INTRODUCTION

Never Laugh at Live Philosophers

Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson

In a hole in the ground there lived a man who passed a quiet, uneventful life in a community that greatly prized convention and respectability. One day, however, he left his hole and journeyed off into the Blue. His adventure, though frightening and at times painful, changed him forever. His eyes were opened, and he matured in mind and character. When he returned to his hole, his neighbors regarded him as “cracked” because they couldn’t accept that there is more to life than order and predictable routine. Although he lost his reputation, he never regretted going on the adventure that enabled him to discover his true self and to experience an exciting new world.

If this sounds familiar, it should. It’s Plato’s (ca. 428–348 BCE) “The Allegory of the Cave,” possibly the most famous there-and-back-again story ever told. Plato’s tale isn’t about hobbits or wizards, of course. It’s a parable about a man, shackled since birth in an underground prison, who ventures forth and discovers that the world is far larger, richer, and more beautiful than he had imagined. Plato hoped that the readers would learn a few lessons from the allegory, such as these: Be adventurous. Get out of your comfort zone. Admit your limitations and be open to new ideas and higher truths. Only by confronting challenges and taking risks can we grow and discover what we are capable of becoming. These lessons are essentially the same ones that J. R. R. Tolkien teaches in The Hobbit.

The Hobbit, one of the best-loved children’s books of all time and the enchanting prequel to The Lord of the Rings, raises a host of deep questions to ponder. Are adventures simply “nasty, disturbing, uncomfortable things” that “make you late for dinner,” or can they be exciting and potentially life changing? Should food and cheer and song be valued above hoarded gold? Was life better in preindustrial times when there was “less noise and more green”? Can we trust people “as kind as summer” to use powerful technologies responsibly, or should these technologies be carefully regulated or destroyed, lest they fall into the hands of the goblins and servants of the Necromancer?

What duties do friends have to one another? Should mercy be extended even to those who deserve to die? Was the Arkenstone really Bilbo’s to give? How should Smaug’s treasure have been distributed? Did Thorin leave his “beautiful golden harp” at Bag-End when he headed out into the Wild? If so, how much could we get for that on eBay? From the happy halls of Elrond’s Last Homely House to Gollum’s “slimy island of rock,” great philosophical questions are posed for old fans and new readers.

Tolkien—all praise to his wine and ale!—was an Oxford professor of medieval English, not a professional philosopher. But as recent books such as Peter Kreeft’s The Philosophy of Tolkien, Patrick Curry’s Defending Middle-Earth, and our own The Lord of the Rings and Philosophy make clear, Tolkien was a profoundly learned scholar who reflected deeply on the big questions. The story goes that while laboriously grading exams one fine summer day, the Oxford professor came across a blank piece of paper. After losing himself in thought for some time, Tolkien allegedly picked up his pen and wrote his famous opening, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

Peter Jackson—may the hair on his toes never fall out!—returns to the director’s chair for The Hobbit (2012), after taking home an Academy Award for his stellar direction of the three Lord of the Rings films (2001–2003). Hobbits may be small, but Jackson and New Line Cinema are going big, stretching the story into two movies, bringing back much of the cast from The Lord of the Rings films, and filming in 3D. After a dark and conflict-filled decade, fans of Middle-earth can finally watch Jackson’s latest installment of the greatest fantasy epic of our time.

In this book, our merry band of philosophers shares Tolkien’s enthusiasm for philosophical questions of “immense antiquity,” but we also keep our “detachable party hoods” close at hand. Above all, this is a book written for Tolkien fans by Tolkien fans. Like other volumes in the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series, it seeks to use popular culture as a hook to teach and popularize the ideas of the great thinkers.

Some of the chapters explore the philosophy of The Hobbit—the key values and big-picture assumptions that provide the moral and conceptual backdrop of the story—and others use themes from the book to illustrate various philosophical ideas. In this way, we hope to both explore some of the deeper questions in The Hobbit and also teach some powerful philosophical ideas.

Much like hobbits, our authors “have a fund of wisdom and wise sayings that men have mostly never heard of or forgotten long ago.” So pack your pipe with your best Old Toby and bring out that special bottle of Old Winyards you’ve been saving. It’s going to be quite an adventure.

PART ONE

DISCOVER YOUR INNER TOOK

Chapter 1

THE ADVENTUROUS HOBBIT

Gregory Bassham

The gem cannot be polished without friction, nor man perfected without trials.

—Confucius

The Hobbit is a tale of adventure. It is also a story of personal growth. At the beginning of the tale, Bilbo is a conventional, unadventurous, comfort-loving hobbit. As the story progresses, he grows in courage, wisdom, and self-confidence. The Hobbit is similar in this respect to The Lord of the Rings. Both are tales, J. R. R. Tolkien informs us, of the ennoblement of the humble.1 Both are stories of ordinary persons—small in the eyes of the “wise” and powerful—who accomplish great things and achieve heroic stature by accepting challenges, enduring hardships, and drawing on unsuspected strengths of character and will.

What’s the connection between an adventurous spirit and personal growth? How can challenge and risk—a willingness to leave our own safe and comfy hobbit-holes—make us stronger, happier, and more confident individuals? Let’s see what Bilbo and the great thinkers can teach us about growth and human potential.

A Hobbit’s Progress

Hobbits in general are not an adventurous folk—quite the opposite. Hobbits “love peace and quiet and good tilled earth”; have never been warlike or fought among themselves; take great delight in the simple pleasures of eating, drinking, smoking, and partying; rarely travel; and consider “queer” any hobbit who has adventures or does anything out of the ordinary.2

Bilbo is an unusual hobbit in this regard. His mother, the famous Belladonna Took, belonged to a clan, the Tooks, who were not only rich but also notorious for their love of adventure. One of Bilbo’s uncles, Isengar, was rumored to have “gone to sea” in his youth, and another uncle, Hildifons, “went off on a journey and never returned.” Bilbo’s remote ancestor, Bandobras “Bullroarer” Took, was famous in hobbit lore for knocking a goblin king’s head off with a club. The head rolled down a rabbit hole, and thus Bullroarer simultaneously won the Battle of Green Fields and invented the game of golf.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!