8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

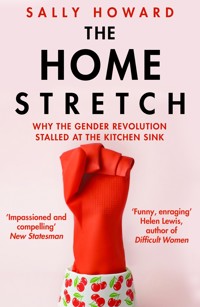

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Forty years of feminism and still women do the majority of the housework. Why? In fact, while women are making slow but steady gains on gender disparities in the workplace, at home the gap is widening - in the UK, the average heterosexual British woman puts in 12 more days of household labour per year than her male companion, while young American men are now twice as likely as their fathers to think a woman's place is in the home. And when 'having it all' so often means hiring a nanny or cleaner, is it something to aspire to? Sally Howard joins up with a cohort of feminist separatists, undertakes a day's shift with her Lithuanian cleaner, lives in a futuristic model home designed to anticipate our needs and meets latte papas and one-percent parents in this lively examination which combines history and fieldwork with her personal story. The Home Stretch is a fascinating investigation into how we got here and what the future could look like for feminism's final frontier: the domestic labour gap.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Sally Howard is a journalist specializing in gender, social affairs and responsible travel. She is a regular contributor to the Sunday Times, the Telegraph magazine, the British Medical Journal, BBC Radio Four’s From Our Own Correspondent and US feminist glossy Ms. magazine. Her first book, The Kama Sutra Diaries, was one of the Scotsman’s Travel Books of the Year for 2014. She lectures on gender and media at institutions including the University of London. She lives in London.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 byAtlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books

Copyright © Sally Howard, 2020

The moral right of Sally Howard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 78649 759 8

E-book ISBN 978 1 78649 758 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ginny and Mary;and Tim, for all you do

Contents

Introduction

1 Coming Clean

2 Battles on the Home Front, a Recent History

3 Paint it Pink and Blue: Naturalizing Gendered Chores

4 The Mother of All Reality Checks (aka the Parent Labour Trap)

5 The Domestic Backlash

6 Power, Money, Willingness to Mop

7 The Outsourced Wife

8 Mrs Robot

9 Marketing Yummy Mummy (or The New Sexed Sell)

10 A Case for the Commons (and Why Separatists Still Struggle with Who Scrubs the Loo)

11 Don’t Iron While the Strike is Hot!

Conclusion: Home Truths

Postscript

Acknowledgements

Picture Credits

Endnotes

Introduction

In the 2019 version of this introduction, I wrote of my surprise to discover that new motherhood had cast me, shredded nipples and all, up against the sexist social expectations around household labour that I, as a feminist, had sought to free myself from. I spoke of my shock, in the sleepless small hours, in discovering that although I’d entered the great experiment of reproduction with a faultlessly egalitarian male partner, I was the one, I was the ‘mum’, with whom the buck stopped. It was me – mum/me – who knew the temperature the milk had to be; who knew if we owned enough babygros in the right size and if they’d been washed. I knew what we’d feed Leo for his first meal, that it couldn’t include salt or honey, where he stood on the baby-weight percentiles and to whom we owed thank you letters for that teetering stack of pointless baby bootees. In short, the categories of work popular feminism has come to term ‘emotional labour’ and ‘the mental load’ fell, inexorably, to me.

From the point of view of the system shock that arrived a few weeks after this book’s initial release, these concerns now seem partial and quaint. The Covid pandemic has wrought a grim toll across the world, costing, as I write this, over a million lives and many more livelihoods. Men, it quickly became clear, were more likely to die of the virus, but it was women who bore the brunt of its social impact. With breathtaking speed, the pandemic ripped up dual-earner couples’ fragile pact: we can both work because there is someone else to look after the kids (and maybe clean the loo). In Spring 2020, when much of the Western world went into its first lockdown, there was no one to look after the kids; no one to school the kids; no one to supply the tens of meals a week that Britons consumed away from home before the pandemic struck. Sectors disproportionately staffed by women – retail, arts and hospitality – were shuttered, as other women who worked in ‘pink-collar’ occupations – caring, cleaning, nursing – laboured on the Covid frontline with inadequate protection or recompense.

By late spring, data began to corroborate a picture many women were already intimate with. A report from the UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies found that women working from home during lockdown were interrupted 50 percent more frequently than men, that women were combining paid work with other activities (almost always childcare) in 47 percent of their work hours and that, while fathers were contributing more to the domestic load in absolute terms (undertaking some childcare during eight hours of the day, compared with four hours in 2014/15), gendered asymmetries of effort had carried over into the new Covid era, with women putting in 60 percent more childcare and housework, undertaking these labours 13 hours a day. By September, an estimated one in four working women in the US, according to a poll of 40,000 people at 317 American firms by consultancy McKinsey & Company, were considering quitting their jobs due to the pressures of juggling home and work life during the pandemic.

And so Spring 2020 found me, fresh from penning this feminist interrogation of housework, taking on the lion’s share of childcare and housework in a heterosexual family life that had shrunk to our domestic four walls. Like many, my partner Tim and I were left to marinade in our domestic accommodations and fixes: how would our delicate balance of housework ‘work’ now nursery or grandparental childcare were out and I had to make the cold calculation of prioritising Tim’s breadwinner wage over my flimsy freelance one? Tim, stooped over an occasional table in the corner of our bedroom, wrangled corporate expectations of staff 9-5 presenteeism in a home that had become, simultaneously, two workplaces and a crèche.

It was a stark moment in which many of us realised how fragile feminist gains are. But many of us too found in this systemic crisis cause for hope. The calls of many feminists to make visible the necessity of domestic labour and carework to all of our lives were being answered with a sudden societal valorisation of the work that falls to women. Overnight, cleaners, care-home workers and nurses were our ‘Covid heroes’. ‘We’re professionals. Give us PPE and better pay,’ the chairwoman of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nicki Credland, told BBC’s Newsnight as she rejected the ‘unhelpful’ celebration of NHS nurses as ‘angels’. And there are other reasons for hope. The argument has been saliently made for the flexible and home-based working for which those with caring responsibilities have fought for decades, against workplace resistance. Home-working fathers are putting in more childcare, and might continue doing so after the pandemic recedes. The new communalism I predict at the book’s end is also tentatively coming to pass, in the rise of shared allotmenting and a street-level mutual aid revolution. Across the West, the pandemic has encouraged us to rely on our local communities, and their shared resources, to survive a challenging time. In these budding signs of new, community-rooted domestic lives we should all find cause for optimism.

*

It was during a bleak night of insomnia brought on by six months of shifting night feeds that I discovered an essay written by Judy Brady for Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine in 1971. Titled ‘I Want a Wife’,1 it spoke poetically of the invisible role women/wives/mothers perform in the smooth running of family lives. Brady opens by explaining that a newly divorced male friend is on the hunt for a brand-new wife, and it had occurred to her that she could do with a wife of her own. With a wife, she could return to her studies, become better qualified, get a new job and become financially independent, while her wife committed all of her energies to making Brady’s life as pleasant as possible.

I want a wife who knows that sometimes I need a night out by myself…

I want a wife who will take care of the details of my social life… [and] the baby-sitting arrangements…

I want a wife to keep track of the children’s doctor and dentist appointments…

I want a wife who takes care of the children when they are sick…

My wife must arrange to lose time at work and not lose her job.

This 47-year-old essay, it struck me, had barely aged. In it I heard the voices of the harried women I’d met through mothering classes who’d found themselves sidelined in the workplace after maternity leave; friends who’d been forced into freelance work to keep up with their children’s schools’ growing demands for attending concerts and fundraisers and, in the words of a North London single-mum acquaintance, ‘knocking up fucking Victoria sponges with a day’s notice’. Women who juggled these swelling domestic demands with all the finesse of a drunk unicyclist and had slowly, inexorably, begun to despise their other halves. Brady’s essay speaks to domestic labour,2 but also the smoothing and facilitating labour that women in heterosexual unions disproportionately undertake. To be Brady’s ‘wife’ is to be a sponge: wives absorb every problem, obstacle and distraction, and ensure that a husband/partner’s path to success and self-fulfilment is set in a smooth, straight line.

Around the same time, I read about the work of 1970s feminist activists Wages for Housework. In 1972, at the height of Second Wave feminism, an international collective of feminists from Italy, England and the USA gathered in Padua to give voice to women’s daily grind. The campaign that came out of that conference positioned housework as an issue of capitalist abuse. It was capitalism, they argued, that most profited from women’s unpaid labour — on their backs, on their knees — in the patriarchal home. In the language of the Marxist left, from which Wages for Housework had sprung, these activists declared women ‘double proletariats’: abused by a capitalist-patriarchal system that underpaid them in the workforce (in 1972, working women earned on average 58 per cent of the male wage*) at the same time as their labours at home were relegated to the status of ‘nonwork’, ascribed to them on the basis of the shape of their genitals and expected to be conducted out of love. Well, they said, let’s put an end to ‘cooking, smiling and fucking’3 for capital — women should organize and REVOLT! It was heady talk, and tens of thousands of women joined the cause, in the US, UK and across Europe.

Today, Wages for Housework is a curio remembered by few other than feminist historians. By the 1980s, the postmodernist turn refocused attentions in popular and academic feminism:** on gender as a social construction; on popular cultural representations of women; and, vitally, on white feminism’s erasure of the lived experiences of women of colour and the way in which oppressions through race, class and gender inform each other. The preoccupations of these 1970s socialist feminists became stuffy artefacts, relegated to history alongside symbolic bra-burning (a gesture that was always more caricatured than practised). The work the Second Wave feminists had undertaken for years on behalf of women and homemakers had become, in a bitter irony, as invisible as the labour itself.

Somehow, in the short generation from the 1970s to the 2010s, the era in which I came of age, the emancipating feminist pronouncement ‘Girls can do anything!’ was mangled into the edict ‘Women must do everything’. This was when, as Barbara Ehrenreich puts it, feminism — after a few concessions — suffered its ‘micro-defeat’ in the home.

Of course, the labour these Second Wave feminists had theorized had gone nowhere. Bottoms still needed to be wiped and toilet bowls cleaned, and the hand that pushed the sponge and thrust the brush was still, invariably, female. From the mid-1980s in the UK, as elsewhere in the rich world, it was as likely to be the hand of a lowly paid migrant woman as that of an unpaid spouse. The ‘problem’ of the gendered attribution of domestic labour was offloaded down a classed and racialized female labour line, and liberal feminism opened a new door for women: the servant’s entrance.

Many men, of course, do much more housework and childcare than they did in the 1970s. In the UK’s Office for National Statistics 2016 Time Use Survey,* British men reported putting in an average of 18 hours a week of domestic effort, including laundry, cooking and cleaning; compared to the average 1 hour and 20 minutes of a 1971 man. Yet these efforts fall far below the 36 hours a week that female Britons contribute to household chores.

British men’s scanty efforts on the home front garner them a cool five extra hours of leisure time, compared to women, each week.4 The picture is similarly lopsided elsewhere. In the US, men contribute 7 hours a week to women’s 17; French men 10 to French women’s 20; and Australian women 15 hours to an Australian male’s 5 hours. Meanwhile, women in Italy devote 24.5 hours a week to men’s 3.5, and men in Portugal manage to rouse themselves for less than 3 hours a week (to Portuguese women’s 22). Even in Sweden — where gender equality is a government project — women put in 45 minutes a day more, on average, than their male counterparts.

And these figures, of course, do not account for the many extra hours women spend on those ‘silent’ categories of domestic labour: the mental load of assuming the responsibility of running a home; chivvying unwilling partners; or the wearing emotional labour of keeping everyone happy and maintaining extended family relationships.

Delve deeper and the statistics are more baffling. After a decade of slow gains from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s, in many rich nations the domestic labour gap stopped narrowing at some point in the 1990s.* Indeed, in the US and UK, male contributions have gone into reverse, with today’s 30- and 40-something British men putting in almost two fewer hours per week of core housework (excluding care) than their similarly aged counterparts in 1998,5 and their US counterparts reducing their inputs by an hour a week.6 Clearly, the increasing entrance of women into the paid workforce, a trend that took flight in the 1980s across the West, hasn’t influenced these asymmetries in the way we had hoped. In heterosexual households where the woman is the main breadwinner, the more the woman earns, the less her partner will contribute — proportionally — to household chores.7

So what happened to the promise of egalitarian households the Second Wave feminists held so dear? Why have gains women have made in the public domain (a quadrupling of women CEOs of US Fortune 500 companies since 1995; the narrowing of the gender pay gap by 20 per cent since 1980; a global doubling of female parliamentarians since the mid-1990s8) been met with backsliding on the home front? ‘Everybody’s in favour of equal pay, but nobody’s in favour of doing the dishes,’ said activist Mary Jo Bane, of the Wellesley Women’s Research Center, in 1977. Little, apparently, has changed.

But the answer is not as simple as blaming a nation of heterosexist jerks who feel entitled to glug beer and watch Top Gear rather than scour the pans, although such jerks definitively exist. As we’ll see, the roots of this stalled feminist revolution reach deep: the stories we tell ourselves about masculinity and femininity; the gender norms that pervade our homes like the aroma of cheap fabric softener; the intergenerational patterning from our mothers and grandmothers, fathers and grandfathers. They arise from the Parent Labour Trap: the fact that economic and structural forces discipline many of us, however much we hope or struggle to avoid it, into traditional gendered roles when kids arrive on the scene. Childless young women often think these battles have been won, but — as we’ll see — the blitheness with which we celebrate feminism’s achievements masks myriad stubborn realities behind the closed doors of family homes.

In 1963’s The Feminine Mystique, American journalist Betty Friedan portrayed the quiet, pill-popping desperation of a nation of women in thrall to the post-war cult of feminine domesticity. Her book — based on a survey conducted amongst fellow alumni of the all-female Smith College — articulated the ‘problem with no name’: that the exclusively wife-and-mother role prescribed as the route to post-war feminine fulfilment was a lie and a trap. In 2020, cultural messaging no longer tells women that their sole route to feminine fulfilment is through the wiping of runny toddlers’ noses and the rustling up of soufflés for husbands commuting home from 9-to-5s. But the cult of the domestic feminine has, nevertheless, proved surprisingly plastic, metamorphosing into the cultural tropes of ‘yummy mummies’, domestic goddesses and have-it-all mums on whom falls the expectation of being ‘super’ both at work and at home, and at the same time performing the ‘aesthetic labour’ of being easy on the eye. Our survey* finds that 59 per cent of women, and 76 per cent of heterosexual women, still consider a clean and tidy home to be a marker of their self-worth. Friedan’s problem with no name, as feminist essayist Katha Pollitt puts it, has become the ‘no-problem problem’.

There are more pressing reasons to address the domestic labour gap than our pursuit of fair and harmonious households. Recent studies point to a raft of implications arising from these asymmetries, from higher anxiety levels amongst the children of rowing heterosexual couples, to the damaging effects of double-shifting on women’s physical and mental health. Moreover, the fact that women in the West earn 20 per cent less than men, for all of national governments’ attempts to shame employers into tackling the issue upstream, is in large part down to the Double Day of motherhood. The woman who leaves work because her son is sick is the woman who’s passed over for a promotion, while the man who marries sees his income and status rise. Gendered labour inequalities at home reproduce gender inequalities in the workplace, in an ever-increasing circle of rising anxiety and dwindling time. As one feminist wit puts it: ‘It’s not a glass ceiling, it’s the sticky floor, stupid.’

Feminist theory gives us new terms for the myriad invisible tasks that fall to modern women: Arlie Hochschild’s ‘emotional labour’ for the feminized work of smiling and soothing, of easing intergenerational family relationships and managing our own emotions according to social rules; ‘mental load’ for the work of taking responsibility that’s in part captured by that old formation ‘good housekeeping’, and which I like to call (wo)management.

From domestic violence to everyday sexism, the glass ceiling and systematic wartime rape, the coining of concepts is often the first step in calling attention to injustices. But — much as feminists might hope for this — we can’t simply rely on the trickle-down of feminist ideas to effect real change in our material lives. And the devaluation of the work of washing and wiping — of, more broadly, the labour of caring for the young, the ill and elderly – is something that intimately affects us all, even for those of us who have managed to escape the Double Day.

Second Wave feminism gave us the insight that household labour is invisible in two ways: as an expression of male privilege and as work. But they — we — left a job half done: our revolutionary pots half washed, our ironing pile in disarray.

Our challenge, and it’s a moral as well as a feminist one, is to bring politics back to the kitchen sink.

_______________

* Rich-world average.

** Then Women’s Studies — now, broadly, Gender Studies.

* The last available.

* In the UK the gap stopped narrowing in 1986; in the US it was 1988.

* An anonymous questionnaire of 1,081 partnered individuals between the ages of 17 and 70, in Europe, the USA, the Antipodes and South Asia. See p. 10 for methodology.

A Note on Survey Methodology

Some of the data that forms this book came from an anonymous questionnaire of 1,081 partnered individuals aged between the ages of 17 and 70 in Europe, the USA, the Antipodes and South Asia. This was, by design, a qualitative rather than quantitative study, with large text fields designed principally to gather anecdotal, rather than statistical, information about respondents’ intimate domestic experience. Although this voluntarily reported qualitative survey disproportionately attracted heterosexual mothers, I corrected for this bias, to a limited extent, by reaching out to groups that were under- or unrepresented (notably older gay males).

Despite such attempts, this survey can only be a partial and imperfect reflection of the intimate domestic realities in these global contexts at our point of time, and I make all due apologies for these shortcomings. The questions used in the questionnaire and a full description of methodology can be found online.9 Throughout, the material derived from the survey is marked in italics.

1

Coming Clean

My grandmother Mary was the first woman in her West Yorkshire village to abandon wartime tweeds for Dior’s New Look. The arrival of nipped waists and full-skirted crinolines marked more than an end to fabric rationing; Mary’s womanly silhouette embodied a cultural mood that sought to reposition Britain’s wartime ambulance drivers, shopkeepers and munitions workers in their rightful place: tending hearth and home.

Mary was a trendsetter for another reason — she was the first to own one of the ‘twin tub’ washing machines which, in their whirring, boxy white form, signalled one of technology’s answers to the perennial slog of keeping house in the 1950s. Soon, the Yorkshire-built mangle that sat by the outdoor coal scuttle disappeared, and with it the copper pot that doubled, at Christmas time, as a steamer of suet puddings, carefully wrapped in sheaths of muslin. Food rationing still had four years to run — the bananas that formed the centrepiece of Mary’s 1960s trifles were yet to arrive, and carrots still bulked up her Christmas fruit cake — but for the Greatest Generation, a brave new world had arrived on the doorstep in the form of electric carpet sweepers, skittering twin tubs and Morphy Richards electric steam irons.

It only fleetingly occurred to Mary, as she carefully pressed the turn-ups into my grandfather’s tweeds, that she missed the day-to-day conviviality of the munitions factory line in York. Life, after all, was tangibly easier for her than it had been for her mother Elsie. At Mary’s age, Elsie was struggling to maintain a household of small children at a time when husbands and sons returned wounded and shell-shocked from the First World War. One bright morning in 1921, three years after her husband Percival had returned from the Front, Elsie walked out onto the moorland surrounding the family’s Yorkshirestone farmhouse at Blackmoorfoot, slipped the cool barrel of Percival’s shotgun into her mouth, and pulled the trigger. The poacher who discovered her body would remark to a local newspaper on the shade of her hair: a glowing auburn that echoed the late-blooming heather on which she fell.

When pressed, in later years, about her mother’s death, my grandmother would softly repeat the family adage that Elsie’s was ‘a mother’s trouble’.

A mother’s trouble. I remember grappling, as a child, with this phrase, redolent as it was of things-between-women and gynaecological discomfort. It took me until adulthood to understand that my grandmother Mary had in mind two specific troubles: the episodic mental illness we’d now call postpartum depression, and the drudgery of keeping a young family fed and warm with a generation of men unable to work for a wage.

The Lost Generation’s lot on the home front was as brutal as it was on the deathly battlefields of France. Many of the young men who’d left in Kitchener’s Pals battalions for the Front — which included 1,659 men from Elsie and Percival’s small quarter of West Yorkshire — would never return home. Of those that did, many were broken by their experience: wheezing from chlorine gas attacks, haunted by the daily horror movie of nightmares and flashbacks. Amongst the young women of Elsie’s generation who were single at the outbreak of the First World War, only one in ten would marry.10 It fell to these ‘silent widows’ and ‘surplus women’ to hold domestic life together — and care for the sick and wounded — on a shoestring.

In 1921, only 6 per cent of British homes were wired for electricity. Coal-gas lighting — a feature found in 40 per cent of London working-class homes by 1937 — was a big breakthrough, putting paid to the laborious and ancient task of ‘lighting up’, but only a fraction of rural homes benefited from piped coal-gas in the 1920s. Homes such as Elsie’s made do with paraffin lamps, the filling and cleaning of which was a labour-intensive job: lamps needed to be kept half-filled to maintain a flame, and were vulnerable to being extinguished by the draughts that plagued rural dwellings. Cleaning equipment — mops made of old rags, brushes from pigs’ bristles, and birch-handled brooms — had barely changed since the 1600s, and washing up, in the era before modern surfactant detergents, was performed with soda flakes, which left hands cracked and raw. Particularly onerous was the effort to keep homes warm. Cleaning coal-fire grates, setting coal fires and disposing of staining and blackening coal-dust was a never-ending task, particularly in the regions, such as Elsie’s, that burned ash-producing, non-bituminous coal. Meanwhile, laundry day — traditionally Monday — was just that: extending through hours of backbreaking wringing and scrubbing, little aided by technology such as the ‘dolly’ (a wooden, three-legged fabric-twisting device) and ridged wooden scrubbing boards.

In her 1967 Fenland Chronicle, Sybil Marshall enumerates the labour that fell to women such as Elsie in the agricultural regions of Britain at the turn of the 20th century. Up at dawn to sweep, clean and set fires, these women were often called upon to work in the fields between their cooking, food production, washing-up, fire-setting, lighting-up and laundry duties. With menfolk relaxing at nightfall, it fell to women to prepare and clean up after the evening meal, put the children to bed, and make or mend clothes and spin yarn by candle- or lamplight. Women’s working days began when they rose and ended at bedtime. Leisure, for women, was non-existent.

In her 1982 history of housework in the British Isles, A Woman’s Work Is Never Done, Caroline Davidson notes the weighty domestic labour burden that, until the late 20th century, fell upon country women such as Elsie. Unlike city-dwellers, country women typically kept animals and cottage gardens, adding food processing to their list of chores — alongside the production from scratch of goods that could be bought readymade in the city, such as tallow or rush candles and lye, a detergent extracted from wood or plant ashes. Laundry services to ‘put out’* the weekly wash, common in cities by the 1920s, were unknown in the British countryside, and fuel was often harder to come by than in cities and suburbs, where horse-and-cart coal delivery men plied their wares.

The spectre of social attitudes will also have haunted Elsie’s daily grind. Even if the men at Blackmoorfoot had been willing to alleviate the domestic labour burden, in the 1920s the taboo of male involvement would have been a powerful inhibitor.

In Elsie’s day, the first Housework Cult held sway. The 19th century had spelled the end of the pre-industrial ‘family economy’, in which most labour was conducted in and around the family dwelling. With the arrival of industrial capitalism, work was divided into two categories: that which was undertaken for a wage and conducted outside of the home; and that which was unpaid and conducted at home. The latter became a new occupational category of nonwork — or ‘Occupation: Housewife’, as the census records termed it. Emerging as a by-product of this development and reaching its zenith in the 1880s — but persisting well into the 20th century — the Victorian Housework Cult invented the term ‘housework’ as we understand it today: a specific set of tasks ascribed to women that were carried out within the home or on its periphery, unpaid and (supposedly) discrete to the male domain of productive labour. Although men and women seldom shared housework on an equal basis, diaries from the 17th and 18th centuries talk of a climate in which men pitched in at home. The diaries of Nicholas Blundell of Little Crosby, Lancashire, written in the early 1700s, describe the author laying the Christmas table, dressing decorative flower pots for chimneys, making preserves, managing servants and keeping household accounts to make life easier for his wife Frances, who bore him two children in quick succession.

By the 1890s, however, a rigid gendered division of labour had been established in much of the West. In his 1935 memoir, Yorkshire Days and Yorkshire Ways, J. Fairfax-Blakeborough paints a picture of late-Victorian rural Yorkshire in which it was a marker of household honour that men did not lift a finger at home. Wives were expected to address their husbands as ‘master’ and serve them obsequiously – even, as Fairfax-Blakeborough describes it, within days of giving birth. Husbands compelled by character or sympathy to help out on the home front often did so in secret: Caroline Davidson notes that husbands in 1890s Manchester who were caught in the act of pitching in domestically were mocked as ‘mop rags’ and ‘diddy men’.*

The Housework Cult led to the extreme and neurotic state of affairs encapsulated in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, a strange and despotic advisory that prescribes, amongst other pointless tasks, the washing of stair bannisters daily and the zestful ‘shaking’ of curtains. Amongst the middle classes of this era, domestic femininity was frequently performed through the collection and maintenance of dust-gathering lace and knick-knacks (signalling a woman’s ability to afford and manage servants).

Similarly, for working-class women good housekeeping was performed through the propriety and outward appearance of their family’s front step. Styles of doorstep finish varied from region to region — in Salford a substance called ‘blue mould’ was popular; in Wales, chalk was in vogue; and orange-red ruddlestone found favour in the West Yorkshire region where Elsie lived. What united these women was the effort of donning their aprons and getting down on hands and knees with buckets and brushes, to scrub away the thankless muck and grime of industrial streets. In the 1950s, according to historian Virginia Nicholson,11 visitors to working-class terraces would still be greeted by the sight of crouching women scrubbing and chalking their stoops, a space, as Nicholson describes it, where working-class women found happy camaraderie. As late as the 1970s, my grandmother’s neighbour Hilda, in my mother’s recollection, got down on her knees to soap and ruddlestone her Yorkshire-stone threshold. ‘She was set on getting it to what she called a “clean fettle”,’ my mother recalls. ‘She did it into her eighties and I suppose her knees held up because she’d rub them with liniment afterwards.’

Working-class women’s step-scrubbing, in historian Robert Roberts’s interpretation, was designed to broadcast ‘the image of a spotless household into the world at large’ — a spotlessness that was intimately associated with religious and moral virtue. ‘Cleanliness is close to godliness’, the motto of the 19thcentury sanitary reformers,* was accepted wisdom, with dirt and sin the twin moral battlegrounds of the respectable home.

My grandmother Mary and her husband Thomas were brought together, in part, by a cruel coincidence. Six years after Elsie’s suicide and barely two miles east, 33-year-old Hilda Barker had knelt on the cool flagstones of her kitchen floor as her seven-year-old twins Tom and Bob ran errands for customers in the family’s grocery shop downstairs and her newborn son John, the shop pet, giggled on her sister’s hip. The same sister, with an animal scream that her nephew Thomas could still recall as an old man, discovered Hilda an hour later: her head drooping into the oven drawer of the new coal-gas range.

Thomas and Mary married 15 years after Hilda’s death and a few months after Thomas’s return from the front at El Alamein, where he’d been an army engineer. Home life during early marriage, she told me as a child as she reminisced over orange-hued photographs, was happy. Through 50 years of marriage, my grandmother kept more-or-less patient house, tolerant of Thomas’s muddy boots and expressing bright gratitude when he made her a cup of tea; and he rose at 6 a.m. to build the tower of twisted-newspaper kindle to light the coal fire that warmed their 18th-century stone cottage. Thomas served sherry at Saturday-afternoon gatherings with extended family, when they’d put wood shavings down on the floor of the ‘lean-to’ garage and dance to the strains of the new 16-inch gramophone.

Twenty-five years after her mother took delivery of that gleaming twin-tub, my mother Anne, a Home Economics teacher with a good line in sausage plaits, embraced the domestic vogues of the 1970s: the chest-freezer cookbook and the backyard chicken coop. The Home Economics syllabus at the Church of England girls’ school where she taught included ‘family egg dishes’ as well as crafting tasks such as crocheting oven gloves and hand-beading dinner-party napkin rings. At home, she baked hemp-seed biscuits with her hand-reared eggs; rustled up fine salads with the blushing tomatoes that fruited, too briefly, on our suntrap patio; filled the freezer with single portions of coq au vin; and made homemade vanilla yoghurt that my brother and I would steal from the back of the fridge, unscrewing the little yellow jar tops to guiltily eat the contents with our tongues.

Anne in the chicken coop with Hen, Holly, Sammy and Hilda, 1983

It didn’t matter that our chickens Hen, Holly, Sammy and Hilda (and their several avian successors) were cruelly torn apart, limb by limb, by suburban foxes; their carcasses melancholically strewn across box hedges and pampas grass. The coop, and the neatly serried rows of spring beans, were my mother’s bid for the Good Life. If my grandmother’s pocket advisory was Housekeeping Monthly, my mother’s was John Seymour’s Self-Sufficiency, the suburban smallholders’ bible that advised how to press cheese, spin flax and properly construct a goat coop (at a wise distance, apparently, from the caprine peril of the rhododendron bush). Anne’s ambition was her generation’s: to return to a largely imagined British Golden Age of allotments, buttered spuds and hand-reared cattle stock. Much of this misty-eyed nostalgia was, as we’ll see, a backlash to the pace of social change: to British women abandoning the kitchen for the workplace, and all of the anxieties that provoked around how — and by whom — families would be clothed and fed. Keen-eyed feminist readers won’t miss the irony of a generation who’d never had it so good in terms of domestic comforts and technology, and in which men were beginning — however half-heartedly — to pitch in on the domestic front, nostalgically harking back to the ‘natural living’ of an Edwardian era that had been, for many, back-breaking and hard.

Yet my mother hummed as she vacuumed the hessian matting around our ginger Habitat scoop chairs with her upright Electrolux, relieved that the inefficient carpet sweepers had gone the way of her great-aunt Lily’s punishing corsets. She viewed her life, as did many of her contemporaries, with mixed grace. Following a package holiday to the Tarragona resort town of Salou, my father Kenneth had started to produce Friday-night suppers of half-collapsed egg scrambles he optimistically called ‘Spanish’ omelettes. Kenneth also made a stab at the nightly washing-up, tapping Condor Ready Rubbed pipe ash into the gathering suds. He offered a then-generous three hours a week to the labours required to maintain our three-bed semi in the least posh part of Solihull. That said, my mum wouldn’t — as she tells me now — have called herself a feminist. She liked her padded bras with their cups like the Great Pyramid of Giza, and she vaguely imagined feminism might deny her the benefits of her Maybelline Great Lash mascara. Feminism was for other — metropolitan — women.

These days, women of my generation have three times as many gadgets to ease household burdens as my mother did, and five times as many as my grandmother enjoyed.12 We have gadgets to automatically vacuum overnight, or to shush a screaming baby with a mimic of her mother’s heartbeat or by rocking her according to the pitch of her wails; we have technology that controls the heating in individual rooms and warms the oven for our return from work. And it’s easy to swallow the spiel that technology is the answer to our domestic woes. For a few deranged few months of early parenthood, for example, Tim and I became obsessed with the promise of technology to help us survive our newborn’s non-stop, eardrum-punishing screams. We bought Shaun the Sheep, a bulbous ovine that glows red and plays a soundtrack of heartbeats, and, memorably, a Fisher-Price Rock ’n Play that promised ‘the perfect calming combo for your little one’ but which we rechristened the ‘vom box’. None of these gadgets stopped our newborn son from screaming, for three hours daily, at a pitch reminiscent of a beauty salon’s worth of nails being dragged across a chalkboard.

On the surface, my domestic fate is very different to that of the women who preceded me. My mother was too late, for all of her awareness of its arrival, to reap the full benefits of Second Wave feminism, which started to ripple out into the suburbs in the 1970s. However, thanks to the rallies, the activism and the sheer recalcitrance of these women, I grew up in different times: through the Thatcher years of the woman with a baby on her hip and a briefcase in her hand; through the feminism-lite of the Spice Girls and Britpop, when emancipation was restyled as being able to drink the boys under the table and reclaiming female promiscuity as empowerment. So, through my teens and much of my twenties, I naively believed that some, if not all (of course not all), of the feminist battles had been won. If not on the streets — where, as a teenager, I’d been repeatedly wolf-whistled, flashed and groped — then behind domestic closed doors, in the houses of middle-class grown-ups to which I’d graduate when I was done with swilling alcopops and falling off my patent black platform boots into the nearest roadside bush. Yes, we women were still objectified and sexualized, under-represented and underpaid. But we weren’t scrubbing the old man’s Y-fronts over the kitchen sink, were we? Or, at least — not yet being in loco maternis myself — I confidently hoped. I hazily pictured my future life-partner in a long line of progress from Neanderthal man to Homo sapiens: from my workboot-shining grandfather, via my omelette-cobbling dad, to the man I’d end up with, who was as unlikely to step out of his underpants on the bedroom floor as slap my bottom and call me ‘toots’.

Elsie and Hilda, Mary and Anne’s lived experiences are the familial recent histories of many of us in the West — women navigating the impacts of Christian cleanliness doctrines, gendered ideologies and the forces of capitalism on the private processes of the home. Many of our great-grandmothers lived hardscrabble lives, while our grandmothers performed domesticity under the shadow of the second, postwar Housework Cult and our mothers were torn between home and productive work. For those of us from non-white and working-class backgrounds, our grandmothers might also have been expected to work for a wage even as they bore the weight of the domestic load. The domestic expectations of patriarchal capitalism might have pressed more heavily on some generations, and some classes of women, but these forces are at work on all of us: disciplining us, forming ideals and inheritances against which we live our gendered home lives.

In recent years, feminists have articulated invisible forms of domestic labour that we might call the Triple Day or ‘third shift’: emotional and mental labour. Coined in 1983 in Arlie Hochschild’s book The Managed Heart, ‘emotional labour’ refers to the work that women are expected to perform in order to smooth relationships and keep the show on the road. These feminized expectations are at play in the working world, of course: feminist academic Silvia Federici calls jobs that expect emotional labour of women — smiling and flirting; complimenting clients — ‘perfume jobs’. However, it’s at home that these ‘womanly skills’ come into their own, with women worldwide working overtime to ‘make nice’: keeping kids happy, putting on a smiling face against the drudgery of day-to-day living, and keeping extended family on side.

‘Emotional labour’ is now sometimes used to mean another distinct aspect of women’s third shift: mental load, or mental labour. The concept of the mental load was neatly captured in the feminist cartoon that went viral in 2017: Fallait demander, or You Should’ve Asked. Authored by a French web designer who goes by the name ‘Emma’, it begins with a scene in which a woman arrives for dinner at her male colleague’s family home. The mother of the household bids her a cheery hello as she simultaneously looks after two warring kids, tidies up the kitchen and cooks a casserole; her husband sits down and enjoys a bottle of wine with their guest. When the pot overflows because his wife is performing three tasks simultaneously, the husband races over with an ‘Ohlala, what have you done?’

‘What have I done?’ screams the red-faced wife as their guest looks on. ‘I’ve done everything!’

‘But,’ the husband responds, ‘you should’ve asked! I would’ve helped!’

The comic struck a chord with the hundreds of thousands of women in heterosexual relationships who shared the cartoon on social media, reading in the telling cluelessness of the phrase their own daily experiences of being expected to be the micromanager of their own homes and having to apportion labour to their other half — of bearing the full mental effort of knowing what needs to be done and when.

‘I knew that I would never do ironing for my husband, and that we would share tasks such as cleaning and cooking. I didn’t anticipate that I would need to ask/remind him to do chores, though.’ Woman aged 33–45, UK

‘My dad never did any household chores. That said, my husband is unaware of what to do — I have to “coach” him!’ Woman aged 25–33, Australia

The terminology may be new, but this (wo)management work has a heritage in much earlier feminist thought. In Feeding the Family,13 first published in 1991, feminist theorist Marjorie DeVault terms the wifely labour of juggling and managing (and knocking up fucking Victoria sponges with a day’s notice) the ‘feminine production of normalcy’. Feeding and household management, in DeVault’s view, are ways in which women are schooled to express their identities. Through tasks such as planning my son’s teething meals and picking up my partner’s strewn underwear — the latter being married women’s top domestic complaint in a thread on website Mumsnet — I reaffirm both my relationship to the world and my identity as a gendered individual. I make sense of myself in a value system that I’ve internalized, and which measures my worth through the performance of care. Girls, DeVault argues, are early on recruited into these womanly domestic activities through an expectation placed upon them to be responsible and attentive. As a child, I knew if my younger brother’s nose was wiped or his homework was done (they rarely were); today, I know there’s tea and biscuits in the cupboard in case the in-laws pop round, and that a birthday card and stamps have been bought for my partner’s cousin’s son. Because if there’s no milk for the Assam or the card goes unsent, it’s me — not their blood relation — who will be judged. Through the day-in, day-out repetition of domestic activities, I ‘fix’ the meaning — to me and to the world — of what it is to be a woman.

In 1985’s The Gender Factory, which looked at the distribution of work in US households, Sarah Fenstermaker Berk similarly offers a ‘gender performance’-based explanation for the fact that, even in two-paycheque families, women consistently put in more work to maintain households than men. Berk argues that ‘gendered identity formation’ takes precedence, in both household and society, over economic efficiency or even fairness: in short, the sense that husbands and wives being ‘good’ men or women trumps a rational approach to division of household labour, even in households with egalitarian aspirations. For Berk, this work that women are expected to do to achieve ‘womanliness’, or for love, is necessarily unremitting. There’s never enough time to satisfy a (largely imagined) hunger for the productions of expert mothering: organic home-cooked food; interior decor to a hotel standard; hand-stencilled depictions of the Serengeti on your toddler’s bedroom walls. In Berk’s take, it’s these naturalized expectations — from others, from society and from ourselves — that are the real job women have to take on.

Berk’s model also makes sense of another impediment to my own ambition of setting up a truly egalitarian household: Tim’s unexamined notion of the ‘manliness’ of allotted tasks. He will cook one-pot dishes with a flourish, but will never bake. He’ll happily stroll about the park with baby, Leo’s feet bouncing in a BabyBjörn sling, yet he’s embarrassed to attend any of the proliferating baby-and-parent singing, raving and ‘sensory development’ events peopled by knackered middle-class mothers. He refuses to carry the nappy bag because ‘it looks a bit like a handbag’, but is first to volunteer to change the baby in the cramped bathroom of a London boozer. These hard-wired gendered taboos around masculine and unmasculine tasks are something we all — Tim and I included — need to interrogate (as we will in Chapter Three).

I meet Silvia Federici in the Brooklyn apartment she’s lived in for 40 years. Spring sunshine slants through the window blinds onto books and campaign materials that are piled as high as the Manhattan skyline: the material remnants of four decades of front-line feminist activism. During our two-hour chat, Federici — an elfin 70-something who dresses in top-totoe black — periodically leaps up to rootle about in the piles’ lower storeys, for an arcane document from the 1970s or a well-thumbed book. ‘No, no, ah! No…’ she says. ‘It’s here somewhere, here somewhere… But where?’

Federici is not, she says, at all surprised by my household’s domestic impasse. Then she inhales a draught of the strong black filter coffee she plies me with from her permanently bubbling stovetop pot. After half a cup, I’m so wired that my left eye has started twitching involuntarily.

‘Women, I am sorry to say it, are in a sad position,’ she explains. ‘What capitalism and patriarchy expect from women everywhere in the world is an impossibility: working for less and less pay, and also performing all of the reproductive labour. This is an impossible situation.’

The co-founder of Wages for Housework, Federici was a leading light in the feminist movement that sought to make sense of the interplay of work and capital, as understood by the left from a feminist perspective. Importantly, Federici added the dimension of reproduction to Marx’s construction of productive labour, or the work capitalism extracts from the worker to derive profit. For Federici, the subordinate status of women hung on this hidden exploitation of women by capital and patriarchy in the home.