12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

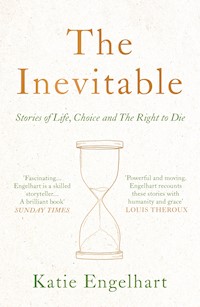

BOOK OF THE YEAR IN SPECTATOR AND TIMES 'Fascinating.... Deeply disturbing... Brilliant' Sunday Times 'Powerful and moving.' Louis Theroux Meet Adam. He's twenty-seven years old, articulate and attractive. He also wants to die. Should he be helped? And by whom? In The Inevitable, award-winning journalist Katie Engelhart explores one of our most abiding taboos: assisted dying. From Avril, the 80-year-old British woman illegally importing pentobarbital, to the Australian doctor dispensing suicide manuals online, Engelhart travels the world to hear the stories of those on the quest for a 'good death'. At once intensely troubling and profoundly moving, The Inevitable interrogates our most uncomfortable moral questions. Should a young woman facing imminent paralysis be allowed to end her life with a doctor's help? Should we be free to die painlessly before dementia takes our mind? Or to choose death over old age? A deeply reported portrait of everyday people struggling to make impossible decisions, The Inevitable sheds crucial light on what it means to flourish, live and die.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Katie Engelhart is a writer and documentary filmmaker with NBC. She previously worked as a UK-based correspondent and presenter for VICE News. She is the recipient of numerous journalism awards, including the American National Magazine Award, the Canadian National Magazine Award and the British Broadcasting Award.

First published in the United States in 2021 by St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Katie Engelhart, 2021

The moral right of Katie Engelhart to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 564 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 565 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my parents

CONTENTS

A Note on Sources

Introduction

1. Modern Medicine

2. Age

3. Body

4. Memory

5. Mind

6. Freedom

The End

Acknowledgments

A Timeline

Notes

If suicide is allowed then everything is allowed. If anything is not allowed, then suicide is not allowed.

—LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN, Notebooks,1914–1916

How can reason not reasonably detest and fear the end of reason?

—JULIAN BARNES, Nothing to Be Frightened Of, 2008

A NOTE ON SOURCES

Where indicated with an asterisk, I have used a pseudonym and sometimes changed several identifying details to protect the privacy of the person concerned. Otherwise, all names and details are real.

Introduction

Betty* said that she would go to Mexico herself. “I’m going to do it,” she told the others. Lots of people went to Tijuana, but Betty chose Tecate, a small city off Federal Highway 2 surrounded by mountains. She had read in her online suicide manual about Mexican pet stores where in-the-know foreigners could buy lethal poison. All you had to do was tell the employee at the register that your dog was very sick and needed to be put to sleep—and that you were there to buy the sleeping agent. “I’m on the case,” Betty texted her friends from outside a local shop. She was a little bit scared, but not too scared. She didn’t think the police would seriously target a woman in her seventies. “They’re not going to go after a little old lady,” she said. “And I could pull the little-old-lady cover if I had to. I could sit and cry if I had to. No problem.”

Back in Manhattan, before she left for Mexico, Betty had bought a handful of expensive-looking cosmetics bottles and printed labels to stick on the front of them: FOR SENSITIVE SKIN ONLY. The idea was that she would transfer the pet-store poison into the decoy containers before driving back over the border into California and flying home. The drugs would belong jointly to her and her two best friends. They would hold on to them quietly, in their respective Upper West Side apartments, until someone got sick. “We have a pact,” Betty said. “The first one who gets Alzheimer’s gets the Nembutal.” The fast-acting barbiturate would put the drinker to sleep quickly, but not suddenly. Once she was asleep, her breathing would likely slow over the course of fifteen or twenty minutes, before it stopped.

Betty told me this shortly after we met. It was at a wedding. I was a friend of the bride. She was the mother of the groom. We first spoke outside, on the lawn, beside an old canoe filled with melting ice and bottles of white wine. Later, we talked at her apartment, which had chandeliers in the hallways and a rheumatic wood-paneled elevator. Betty’s reading glasses hung from a cord around her neck, and she put them on and took them off and put them on again, again and again, as we spoke. I hadn’t been looking for her—we met by chance—but when I told Betty about the book I was writing, she laughed and said that she had a story for me. By the time I heard it, I had interviewed enough people to know that all across America, sick and elderly men and women are meticulously planning their final hours: sometimes with bottles from Mexican pet stores or powders from drug dealers in China or gas canisters from the Internet or help from strangers. I also knew that while most reporting about the so-called right to die ends at the margins of the law, there are other stories playing out beyond them. Away from medical offices, legislative chambers, hospital ethics committees, and polite conversation. I knew that this was where I wanted my book to begin.

It had recently occurred to Betty that she had no interest in growing very old or dying very slowly. An old friend was in his nineties and it depressed her to see him still “hanging around.” It depressed him, too. He was brittle and bored, and all his friends were dead already. And still he drifted, almost passively, almost without meaning to, from treatment to treatment. The end of life was strange that way. Betty blamed his doctors, and in turn all doctors. “Their whole education is ‘Save a life! Save a life! Save a life!’ Sometimes they forget what terrible shape people are in.” She believed that it was better to cede to the limits of medicine than to fight them.

Her own husband had died quickly enough. Seventy-five years old. Cancer. Still, he suffered. Sometimes he cried. In his final days, Betty imagined taking firm hold of a pillow and smothering him, partly because she thought that’s what he would have wanted, but also because she couldn’t bear to see him that way. In the end, he grew so agitated that doctors gave him enough painkillers to knock him out. He spent three days in a morphine-induced languor and then died. Betty and her friends agreed that they would never let themselves get to that place and also that they would never rely on a physician to help them, because who knew where the bounds of a doctor’s mercy lay?

Betty had learned about the Mexican drug from an online suicide manual, The Peaceful Pill Handbook, which was published by a fringe right-to-die group called Exit International. “You’re only going to die once,” its author said. “Why settle for anything but the best?” The handbook taught Betty that there was an alternative path. She could kill herself when she wanted to, only it wasn’t as straightforward as most people assumed, if the end goal was a death that was foolproof and quick and painless. Reading through the text, Betty learned that many people try to end their lives and fail, on the weakness of their resolution, or by the foibles of their chosen poison, weapon, severed artery, or high-rise window. Or they take a handful of painkillers and die in writhing agony. Older methods of life ending had also been rendered impractical by advances in medicine and technology, which generally made the world safer, but also made it harder to achieve an easy death. Environmental regulations on the automobile industry had lowered permissible carbon monoxide emission levels, which made it more difficult to end a life by asphyxiation in the old way: running a car in a closed garage and funneling exhaust gas in through the window. Coal gas ovens had been replaced by less lethal natural gas equivalents. First-generation sleeping pills had been phased out and replaced with medicines that weren’t as easy to overdose on. Even sympathetic doctors would have a hard time prescribing lethal pills to sick and dying patients like they used to: discreetly and quietly and with important things left off the patient’s medical charts. Betty’s book advised readers to acquire one of several drugs to hold for safekeeping and to use when the time was right.

Betty warned her friends that they would have to be careful in their planning, because even though suicide is legal, it is against the law to help someone else do it. Besides, if the wrong person found out, the women could find themselves under lockdown psychiatric watch, stripped of their belts and shoelaces and privacy, for hours or days. Interrogated and observed and accused. Betty had never broken the law before, and she didn’t particularly want to. She would have preferred to do things properly: to wait until she was just about ready to die and then ask her doctors to make it so. But physician-assisted death is not legal in New York State. And anyway, even in the US states where it is legal, for terminally ill patients, a person can’t qualify to die just because she is old and tired of living in an elderly body that she no longer wants or relates to.

As it was, she was feeling OK. She went to Pilates every week. She went to the theater. She saw interesting friends and read complicated books. But one day, all of that would end. When it did, Betty hoped that she could summon enough resolve to kill herself. Sometimes, she thought she should just pick an age and promise herself that she would not live beyond it. “There are two types of people in the world,” Betty told me, “those who want to deal with death and get some control over it, and those who don’t want to think about it. . . . I can’t not think about it.”

THE PUSH TO wrest bodily control, at the end of natural life, from the behemoth powers of Big Medicine and the state has been defined by individual stories: generally of white women whose personal end-of-life tragedies became family dramas, and then viral national dramas—and then talking points and turning points in a larger political crusade for “patient autonomy.” In the US, this modern history begins in 1975, when twenty-one-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan went to a party at a bar in New Jersey, where she reportedly chased Valium with a few gin and tonics and then passed out. At the hospital, doctors attached the young woman to a mechanical respirator, but it was too late. Karen Ann’s brain had been without oxygen for so long that it was damaged beyond repair. She was not dead, strictly speaking, but she had entered a “persistent vegetative state.” Her weight dropped from 115 pounds to less than 70. Her eyes opened and shut and moved, but not in the same direction or in tandem. She seemed to grimace, though doctors assured her family that this was nothing more than a mindless muscle spasm. Several weeks later, Joseph and Julia Quinlan asked doctors to turn off their daughter’s respirator, and the doctors refused. Hospital administrators said that removing the machine would lead to Karen Ann’s death and thus would be murder.

The Quinlans filed suit in September 1975. When they did, the fight over young Karen Ann mutated into the nationally televised Quinlan affair. Dozens of journalists packed into the crowded Morristown courtroom and held vigil outside the Quinlan family home, flooding the front door in a wash of paparazzi flashbulbs whenever anyone came or went. The body of the voiceless, featherweight girl seemed to cry out for protection, and soon a cast of would-be saviors appeared. Politicians and priests spoke of rescuing her. Self-described faith healers and prophets arrived in New Jersey, some of them promising miracles—if only they could rest their hands on the “sleeping beauty.” In daily news broadcasts, Karen Ann’s inscrutable sleep assumed the form of a fairy tale or a morality play. In court, lawyers for the family said that Karen Ann deserved to die “with grace and dignity.” On the other side, lawyers representing the hospital doctors compared the Quinlans’ petition to Nazi atrocities during the Holocaust, “like turning on the gas chamber.”

In November 1975, the Quinlans lost their case but quickly appealed to the New Jersey Supreme Court, which reversed the lower-court decision. Justices ruled that Karen Ann’s individual liberty interests were greater than the state’s interest in preserving her life, since doctors saw “no reasonable possibility” that she would get better. By the court’s logic, when doctors turned off Karen Ann’s life support, they would not be murdering her, but instead allowing her “expiration from existing natural causes.” The New Jersey justices referred to this act as “judicious neglect,” though others would call it “passive euthanasia.” Later, at Karen Ann’s funeral, a parish priest named Monsignor Thomas Trapasso gave an anguished homily. He said he prayed that the young woman’s drawn-out end would not “erode society’s concern for the worth of human life. . . . Only time will tell the full impact that Karen Ann’s life and death will have on future ethical practices.”

In 1983, twenty-five-year-old Nancy Cruzan lost control of her car in Carthage, Missouri, while driving home from her job at a nearby cheese factory. She was found facedown in a ditch, not breathing. Again, doctors declared the patient to be in a persistent vegetative state and put her on life support. Again, the woman’s parents insisted that their daughter would have preferred death to a vegetative life, and they asked for her feeding tube to be removed. Again, hospital administrators refused. And once again, the young woman lay in her hospital bed for days and months and then years: her hands and feet contorted inward at unholy angles and her body still, save for the occasional eye flutter or seizure or round of vomiting. This time, the patient’s fate was decided by the US Supreme Court, which in 1990 issued its first-ever ruling in a right-to-die case. In a 5–4 split, justices decided that any competent individual had the right to refuse any medical treatment, regardless of her prognosis or how effective a treatment might be. A patient could, for example, turn down medicine that would save her life. Also, family members and healthcare proxies could refuse treatment on behalf of an incompetent patient, as long as she had left clear evidence of her wishes. Some right-to-die advocates celebrated the decision, but for many Americans there was a creepy element to the court’s ruling; judges had established a right that many people assumed they already had and always had.

When Nancy’s feeding tube was finally withdrawn, she took twelve days to die. It was reported that her lips blistered and cracked and began to protrude. Her tongue swelled and her eyelids dried shut. Americans following her story were left to wonder whether withdrawing a machine and letting a person die of dehydration was so different from letting a doctor give a lethal injection to quickly end a patient’s life, and which was better. “Even a dog in Missouri cannot be legally starved to death,” said one reverend who traveled from Atlanta to stand outside the hospital as Nancy’s body gave way. That same year, a twenty-six-yearold named Terri Schiavo went into cardiac arrest at her Florida home and inspired yet another right-to-die battle: this one pitting the woman’s husband against her parents, with both sides claiming to speak for the unspeaking Terri, who had not left behind a legal will. Over the course of fifteen years, Terri’s feeding tube would be inserted, then withdrawn, then reinserted (on the orders of a judge), then withdrawn again, then reinserted again (on the orders of then Florida governor Jeb Bush), before finally being removed forever in 2005.

Through these women’s stories, a debate over the limits of lawful medical care transformed into a more aching conversation about fundamental rights and eventually into a campaign to take the patient autonomy movement even further. In 1994, Oregon residents passed Measure 16, making the state the first place in the world to legalize, by vote, what was then called assisted suicide, but which now, in the vocabulary of political lobbyists and patients who struggle to distance their cause from the laden s-word, is often called medical aid in dying (MAID) or physician-assisted death (PAD). After a string of legal challenges and a repeal campaign backed by nearly $2 million of Roman Catholic Church funding, the law went into effect in 1997. The Oregon Death with Dignity Act became a historic and moral turning point for the country and the world: a tilt toward utopia, or dystopia, depending on your view of things.

A year later, in 1998, an eighty-four-year-old Portland woman with metastatic breast cancer became the first person in the United States to legally die with her doctor’s help. The woman was known to the public as Helen, and when she first told her doctor that she wanted to die, he said he didn’t want to be involved. A second doctor advised her to enroll in hospice care and wrote in his notes that Helen was probably depressed. Helen found a third doctor. At her first appointment, she arrived in a wheelchair, attached to an oxygen tank. She explained that she had enjoyed living, but that each day was now worse than the day before it. Dr. Peter Reagan sent Helen to a psychiatrist, who spent ninety minutes evaluating her mood and competency before determining that in fact she showed no signs of depression. Reagan, in turn, wrote the woman three prescriptions: two for anti-nausea drugs, and the other for a barbiturate called secobarbital.

Before the Oregon law passed, Reagan told me, he had been “in enough situations where patients asked me for aid in dying. I turned it down because it wasn’t legal. I knew there was a demand and I felt sick from that demand. I felt sick that I couldn’t help people.” But other doctors, Reagan knew, had helped their patients anyway, in the hospital shadows. In a 1996 survey in Washington State, 12 percent of doctors said they had received “one or more explicit requests for physician-assisted suicide” and 4 percent had received “one or more requests for euthanasia.” A quarter of patients who made those requests were given lethal prescriptions. In a separate 1995 study of Michigan oncologists, 22 percent admitted to having participated in “assisted suicide” or “active euthanasia.” And of course, there was Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who had become his own national scandal in 1990 after he helped a fifty-four-year-old Oregon woman take her life in the back of his beat-up Volkswagen van.

The Oregon law required patients to self-administer their lethal medications, so it was Helen who raised the glass of barbiturate to her lips. It took about twenty seconds for her to swallow all the liquid. She was at home with her two children, in the evening. When it was over, she asked for some brandy, but because she wasn’t used to alcohol, she choked a little on the drink. Her daughter Beth rubbed her feet. Dr. Reagan took her small hand in his larger hand and asked how she was doing and Helen’s response to him was the last thing she said. “Tired.”

It was an inauspicious first. “It just happened,” Dr. Reagan told me. He had been a workaday family doctor in Portland. When he agreed to help Helen, he didn’t have any idea that her death would be the first. Then Helen’s story hit the papers. “While doctors, religious leaders and politicians continue to debate the ethics of allowing physicians to help terminally ill patients kill themselves,” wrote New York Times reporter Timothy Egan, “the issue took a sharp turn from the abstract today.” Afterward, Reagan’s name was leaked to reporters and he wondered what would happen to him. Would people throw rocks through his windows? Would they do worse—like they did to abortion doctors? But they did neither. Reagan continued to write prescriptions.

From the start, those opposed to physician-assisted death worried that any right to die would evolve, by tiny and coercive steps, into a duty to die—for the old, the enfeebled, and the disabled. A professor at the Oregon Health and Science University described it more bluntly: “There was a lot of fear that the elderly would be lined up in their R.V.’s at the Oregon border.” But on the other side, advocates argued that a constitutional right to life had been perverted by the exigencies of modern medicine: that it had become, for most Americans, even ones who wanted to end their lives, an enforceable duty to live.

Under the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, an eligible patient has to be terminally ill, with a prognosis of six months or less to live. Prognostication is a fuzzy science, notoriously imprecise, and so two independent physicians must be in agreement. The patient must be over eighteen years old, a resident of the state, and mentally capable at the time of her request. If her doctor suspects that her judgment is impaired, for instance, by a psychological disorder, she should be sent for a mental health evaluation. The patient also has to make two oral requests to die, separated by at least fifteen days, and provide a written request to her attending physician, signed in the presence of two witnesses. Under the law, the patient’s doctor is obliged to explain alternatives to assisted death, like pain management and hospice care, and also to request that she not end her life in a public place. The doctor will recommend that the patient notify her family members but cannot require it. At the heart of the law is the self-administration requirement; the patient needs to take the medication herself, since only assisted dying (where a patient self-administers lethal drugs, usually by drinking a powder solution) and not euthanasia (where a doctor administers the drugs, usually intravenously) is allowed.

When the Death with Dignity Act went into effect, advocates hoped that Oregon would give other states the moral impetus they needed to pass their own equivalent laws. Some proponents saw their movement as the logical continuation of other grand progressive battles: for the abolition of slavery, for women’s suffrage, for racial desegregation. Baby boomers, the theory went, had seen their parents die ugly, protracted hospital deaths and wanted another way. But the post-Oregon elation did not quite play out. In 1995, the Vatican called assisted death a “violation of the divine law.” The American Medical Association also declared itself opposed, on the grounds that “physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as a healer” and his solemn pledge to do no harm. Healing, the thinking went, precluded killing. In the years following, dozens of states debated and rejected their own Oregonstyle statutes. Doctors in Portland came to assume, as one said later, that assisted death would remain “one of those quirky Oregon things.”

In 1997—the year that scientists in Scotland unveiled a cloned sheep named Dolly and Comet Hale-Bopp flew by earth—the US Supreme Court ruled on two assisted-death cases, from Washington and New York. In both cases, justices unanimously decided not to overrule state-level bans on physician assistance in death. In doing so, they concluded that physician aid in dying was not a protected right under the US Constitution. In other words, there was no right to die, or right to die with dignity—or even, in the words of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a “generalized right to ‘commit suicide.’” Instead, the Supreme Court sent the issue back to the “laboratory of the states.” In his principal opinion, Chief Justice William Rehnquist emphasized the state’s interest “in protecting vulnerable groups—including the poor, the elderly, and disabled persons—from abuse, neglect and mistakes.” He also alluded to the slippery-slope argument that had become a backbone of opposition thinking around the world. The theory went that once a limited right to die was granted, it would be impossible to rein it in; the law would inexorably expand and expand to include ever more categories of patients. The sick but not dying. The mentally but not physically ill. The old. The paralyzed. The weak. The disabled. Eventually, critics warned, there would be abuse. Of the poor. The unwilling. The compromised. The scared. The sixteen-year-old boy with a scorching case of unrequited love. Any given principle, US Supreme Court justice Benjamin Cardozo once observed, had a “tendency . . . to expand itself to the limit of its logic.”

Elsewhere, though, legislators had different ideas about sanctity. In 1995, the Northern Territory of Australia legalized euthanasia. While the law was rescinded by the federal government just two years later, the global landscape was slowly shifting. In 1998, “suicide tourists” from around the world started dying in Switzerland, where assisted death had been decriminalized and where a new clinic, near Zurich, began accepting foreign patients. Then in 2002, both the Netherlands and Belgium legalized euthanasia. Later, they were joined by Luxembourg, making the tiny Benelux region the global hub of physician-mediated death.

Around the same time, a legal challenge in Britain failed to overturn the country’s ban on assisted dying. The case was brought by Diane Pretty, a 43-year-old from Luton with motor neurone disease. Diane said she wanted to end her life, but that she couldn’t, because she was paralyzed from the neck down. In this way, she said, her physical inability to suicide, as was her legal right, was depriving her of her human right to die with dignity. Diane, in turn, wanted her husband to kill her – and she wanted to be sure that when he did, he would not be jailed for murder. She brought her claim before a British court, and then the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. On the day she lost her final appeal, in April 2002, Diane addressed a cluster of reporters in London, through a voice simulator. “The law has taken all my rights away,” she said. A month later, she died, after days in terrible pain. She died “in the way she always feared,” the Telegraph reported.

Back in the US, it wasn’t until 2008 that Washington followed Oregon’s lead. Then came Montana (by judicial ruling, rather than legislation); Vermont; Colorado; California; Washington, DC; Hawaii; Maine; and New Jersey. The laws had different names, which made use of different euphemisms: End of Life Options Act (California), Our Care, Our Choice Act (Hawaii), Patient Choice and Control at the End of Life Act (Vermont). According to a 2017 Gallup survey, 73 percent of US adults believe that a doctor should be allowed to end a patient’s life “by some painless means,” if the patient wants it and “has a disease that cannot be cured.” That show of support, however, drops to 67 percent when people are instead asked whether doctors should be allowed to help a patient “commit suicide if the patient requests it.” Language both reflects and shapes opinion, and the s-word still carries its weight.

In Oregon, where the movement started, the numbers have remained small: around 3 out of every 1,000 deaths. In 2019, 290 patients got a lethal prescription and 188 died by ingesting lethal drugs. The vast majority have cancer, while others have heart disease, lung disease, and neurological illnesses like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease). The patients are, more often than not, white and over sixty-five and middle class, married or widowed, with some college education. They score low on measures of spirituality. Almost all have health insurance, and most are already enrolled in hospice care. They have the time and the temperament and the capital to figure out what they want and then get it. Other researchers have offered additional theories. They note that African Americans are generally less likely to access end-of-life care, including palliative and hospice care, and speculate that these same disparities and discriminations extend to aid in dying. They observe that lethal medications are expensive and aren’t always covered by insurance and so are sometimes unaffordable. They insist that certain demographic groups take better care of their elderly than others, and so presumably have fewer older people wanting to kill themselves. They chalk it all up to differences in religiosity and communal belongingness and moral values.

We do know something about what motivates patients to choose early death, in the places where aid in dying is legal. What surprised me most, looking through Oregon Health Authority data, was that most people who ask to die are reportedly not in terrible pain, or even afraid of future pain. The vast majority cite “losing autonomy” as their primary end-of-life concern. Others worry about “loss of dignity,” loss of the ability to engage in enjoyable activities, and “losing control of bodily functions.” Where pain enters the equation, it is a fear of future pain, or a wish to fend off forthcoming pain—or sometimes the here-and-now psychic pain of not knowing how much more pain will come. Will it be a good death or a bad death? The uncertainty is what lends the question its urgency. In the end, patients choose to die for more existential reasons: in response to suffering that falls outside the established borders of modern medicine.

THIS BOOK INCORPORATES medicine, law, history, and philosophy, but it is not a book of argument and it is not a comprehensive accounting of the right-to-die movement. Primarily, it is a collection of stories and conversations and ideas. My work began in London in 2015, when I was working as a journalist at VICE News. That year, the British Parliament voted on whether to legalize physician-assisted death in the country. I did some reporting on the subject and worked with a few colleagues on a documentary film. I followed the national debate, which was both vehement and predictable. Proponents spoke of “personal autonomy” and told wrenching stories about sick and dying people who were driven to end their lives, in hideous ways, because of their pain. Opponents spoke of “the sanctity of life” and warned of a lack of safeguards to protect vulnerable people. On the day of the vote, protesters gathered outside the Parliament building to scream in each other’s faces, purple-faced and bug-eyed. GIVE ME CHOICE OVER MY DEATH, read posters on the one side. BEWARE THE SLIPPERY SLOPE, DO NO HARM, read posters on the other. Later, after Parliament voted down the bill, I continued my own research, first across Britain and then in countries where assisted dying is legal: Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United States. I wanted to know what it meant to legislate a whole new kind of dying into being. It seemed so fundamental to how we understand the meaning of our lives and the social contracts we feel bound to.

When I turned my attention to reporting, I was surprised to find much less data than I had expected. In Belgium and the Netherlands, euthanasia oversight councils publish annual reports, but they reveal little about the individual people who make use of the laws. In the American states where aid in dying is legal, health departments release even less. In these places, physicians are required to turn in some amount of paperwork on each completed death, but these forms are filled out by doctors rather than by dying patients, whose self-reported thoughts and expressions are never captured by the medical system. Not every state collects much data at all, and not all of the collected data is published, because of confidentiality concerns. This leaves some researchers to mourn for all that is never known about these unusual patients—their specific geographic locations, their mental health histories, the nature of their family relationships, the size of their bank accounts. Across the world, systematic research on physician-assisted death is also scant. “There are reasons for that,” Dr. Ganzini, who has published more on the subject than almost anyone else in America, told me. “It’s hard to get it funded. It is the kind of research that, for example, the National Institutes of Health would be wary of.” I knew that if I wanted to understand these patients, I needed to find them, and then to follow them through the brief slivers of time when they were planning their deaths.

But that wasn’t all. As I learned more about US death with dignity laws – the kind that are considered, from time to time, in countries like the UK – they no longer seemed that philosophically radical. The laws, after all, apply only to dying patients who are going to die soon anyway. They speed up an inevitable process, but not by much. And they don’t change its course. As the months and years passed, I started meeting other kinds of patients: men and women who didn’t meet the criteria for physician-assisted death, even where it is legal, but who still wanted to die—for absolutely rational reasons, they said. Because they were chronically ill. Or in pain. Or old and tired, or becoming demented. Or because they didn’t want to live as long and as sick as their parents had. These people were very different from one another, but they seemed to share a common vocabulary. In our conversations they spoke of “rational suicide,” a kind of life ending that is, at least in theory, not impulsive or inspired by mental illness (what is sometimes called “despair suicide,” which is most suicides) but instead by the ostensibly cooler and more sober mathematics of cost-benefit analysis. Given everything: to die or to live?

Many people told me stories about coming up against the limits of the law and then looking for solutions outside them. And finding them. Sometimes, help came in the form of loved ones. Other times, people found relief on the Internet: in small but often highly organized clandestine groups, which some activists refer to as the “euthanasia underground.” When I first learned about these networks, I was amazed by them. But then—well, of course. Hadn’t I read about underground women’s groups that offered abortions in the years before they were legal? Didn’t I know that whenever the law falls short, people find a way? I decided to make these people the focus of my reporting and the protagonists of this book.

Over the course of four years, I spoke with hundreds of people, all over the world, who are, in various ways, involved in assisted death, both within and outside the law. I interviewed patients, doctors, nurses, researchers, dogged advocates, stalwart opponents, a tormented mother, an indignant father, and a grandmother who locked herself in the basement when I arrived to ask questions about her grandson. I connected with a shaman in the desert of New Mexico; a Mexican drug dealer who reads Lao-tzu; several elderly men and women in Britain who ordered lethal drugs on the Internet; and a former corporate executive who travels around the US teaching strangers how to take their lives with gas canisters and plastic bags. In the time we spent together, these people considered the impulse to live and the impulse to die, and the way those inclinations can bend around each other. In the end, I devoted very little attention to the experiences of politicians battling in state legislatures and religious figures who oppose assisted death on theological grounds. Those stories felt too tired, too obvious. Instead, I focused on six personal stories, which make up the six chapters of this book. Two are about doctors: one a physician in California who opened a clinic specializing in assisted death, and the other an Australian named Philip Nitschke who lost his medical license for teaching people how to “exit” at “DIY Death” seminars. Nitschke’s organization, Exit International, and his published suicide manual, The Peaceful Pill Handbook, make appearances throughout this book. The other four chapters belong to people who told me that they wanted to die because they were suffering unbearably—of, respectively, old age, chronic illness, dementia, and mental illness.

Many of the people I met had stories that were messier and more tangled than those I read in daily newspaper reports about physician-assisted dying: tidy narratives about terribly sick people in the US or Belgium who, after receiving their terminal diagnoses, made tortured but lucid choices, in direct and exclusive response to that tumor, or this lung disease, or that neurological failing. The people I met were certainly motivated to die because they were sick, but also because of mental anguish, loneliness, love, shame, long-ago traumas, or a yearning for the approval of Facebook followers. Some were driven by money, or a lack of it. The people I met were not, in other words, pure characters. They weren’t always likable or relatable, or even emotionally legible. They were not always brave in the face of death. And their suffering did not always yield meaningful lessons to impart to the world around them. Sometimes, their pain was just pointless and awful.

My reporting was not straightforward. In several cases, I knew that people had the intention to end their lives before they carried out the act—alone at home, without a doctor’s help or knowledge—and I did not intervene. This work was ethically knotty. I was often unnerved and uncertain, both as a journalist and as a human. As any reporter knows, the story changes as soon as she appears with her notebook and recorder, no matter how unassuming she is or how delicately she navigates the scene. I never wanted my presence in someone’s life to nudge her toward death. I didn’t want anyone to die for the sake of a story, or for the sake of my story. I tried to be careful. I was selective about whom I met with. When possible, I spoke with family members, friends, doctors, therapists, and caregivers. I reminded people, over and over, that they owed me nothing and that I expected nothing. They could speak with me for as long as they wanted to and then tell me to back off. If it was easier, they could just stop answering my calls. Some did, and I let them go.

Over the years, I found myself discussing this book at dinner parties and work functions and crowded bars, and then being sought out later for private confession. It seemed like everyone had a story and was starved to tell it. Why? Near strangers described terrible endings they had witnessed. Unruly. Slow. Embarrassing. Others told me about deaths that had been planned. A friend said his grandfather had hoarded cardiac medication to kill himself with. Another described how her sister had crushed pain pills to stir into an elderly aunt’s yogurt. A colleague told me that his ninety-something father had opted for a needless and risky surgery in the feverish hope that he would die on the operating table. The man was too weak to kill himself, but he hoped that he could make his doctors kill him.

What does this all mean? This hunger for absolute control—or maybe just a shred of control—at the end of life, and this revolt against the machines that sometimes sustain a spiritless version of it? It is about the desire to avoid suffering. It is about autonomy. It is also about the right to privacy and the negative right to not be interfered with. But for most of the people I met, choosing to die at a planned moment was principally about “dignity.”

Dignity, of course, is a muddy sentiment—and some philosophers take issue with the very idea of it. They argue that dignity is, at best, conceptually redundant: another way of saying respect for choice or for autonomy. Others resent its use in this particular fight. Aren’t all humans endowed with an intrinsic dignity, they ask? Isn’t everyone, by extension, dignified when they die? Proponents of medical aid in dying have absorbed the word into their catchphrase euphemism “death with dignity” and so claimed a monopoly on it, but opponents have made their own dignity appeals. “We oppose euthanasia and assisted suicide,” read the 2008 Republican Party platform in a paragraph titled “Maintaining the Sanctity and Dignity of Human Life.” For others, dignity is not found in escaping physical pain, but rather in being calm and courageous and self-restrained in the face of it. Dignity, in this view, is reflected in composure—and earned through endurance.

When I interviewed sick and dying people for this book, I sometimes asked them about dignity. In the beginning, I admit, I found myself expecting a kind of transcendent wisdom from them, as if, by virtue of being especially intimate with mortality, they would understand things in a way that I couldn’t. It wasn’t like that. A lot of people I interviewed equated dignity precisely with sphincter control. Their lives would be dignified, they said, until they shit their pants or had to have someone else wipe their ass. It was really that straightforward. It seemed that even when people had trouble defining dignity in a precise way, they knew intrinsically when something felt undignified. For them, planning death was often about avoiding indignity, something they imagined would be humiliating, degrading, futile, constraining, selfish, ugly, physically immodest, financially ruinous, burdensome, unreasonable, or untrue.

“HOW CAN I explain this? I think it’s virtually impossible for any human being, no matter how old they are, to imagine their own death,” Betty said. We were seated in her dining room, in straight-backed wooden chairs, eating fruit salad. She had just told me about the trip to Mexico and the drugs and the suicide pact. “The resurrection was the best idea to get people to sign up to Christianity that ever existed.” But Betty did not believe in resurrection. The best she could hope for, and the only thing she could plan for, was “a peaceful death,” which she hoped she could achieve by cutting short the very last stretch of her life. She would die before she became so ill or demented that she lost herself. The deep slumber of a barbiturate overdose seemed easy enough.

It was strange, Betty thought, how humans were left to suffer in the end, while dogs got to be put out of their misery with a quick shot of medicine. Strange, too, how the putting down of dogs was seen as an act of mercy. Strange to be envious of dogs! There was a slogan that Betty liked that was shared by right-to-die enthusiasts online: “I would rather die like a dog.”

1

Modern Medicine

The first thing Dr. Lonny Shavelson thought when he stepped into the room was, This is a bad room to die in. It was small and stuffy and there weren’t enough chairs. He would have to rearrange things. He would start by pulling the hospital bed away from the wall, so that anyone who wanted to touch the patient as he died would have easy access to a hand or arm or soft, uncovered foot. But first, there were loved ones to greet. They all stood stiffly by the doorway, and Lonny hugged each of them: the three grown children, the grandson, the puffy-eyed daughter-inlaw, and the stocky, silent friend. Then he sat his slight body down on the edge of the bed. “Bradshaw,” he said gently, looking down at the old man lying under the covers. Bradshaw blinked his eyes and stared vacantly at the doctor. The room smelled sour and institutional, like evaporated urine. “You don’t know who I am yet, because you’re still waking up,” Lonny said buoyantly. “Let me help you a little bit. Do you remember that I’m the doctor who is here to help you die?”

The old man blinked again. Someone had combed his gray hair back, away from his forehead, and he wore a brown cotton T-shirt over thin, age-spotted arms. “It’s the prelude to the final attraction,” Bradshaw said at last.

Lonny, who is small and slim, with a receding hairline and wire-rimmed glasses, left his Berkeley home office that morning at 9 a.m., with a canvas medicine bag in one hand and a pair of black dress shoes in the other. He always wore house slippers when he drove, for comfort, and then changed into nicer shoes when he got to the patient’s home. This would be Lonny’s ninetieth assisted death. Everyone said there was no doctor in California who did more deaths than Lonny. He would say that this had less to do with his particular allure as a physician and more to do with the fact that other doctors in California refused to do assisted deaths or were forbidden to do them by the hospitals and hospices where they worked. Sometimes, Lonny said, he got quiet phone calls from doctors at Catholic health systems. “I have a patient,” the doctors would say. “Can you help?”

Lonny drove north, through residential Berkeley, past tidy streets lined with bungalows and blossoming cherry trees, and then along unattractive stretches of highway dotted with drive-through restaurants and Chinese buffets. After a while, the urban sprawl gave way to water-soaked rice fields. Lonny took tiny sips from his water bottle and tried to memorize the names of the patient and his children. I quizzed him until they came easily. The patient was Bradshaw Perkins Jr. and he was dying of prostate cancer.

Three years earlier, when Bradshaw was living with his son Marc and his daughter-in-law Stephanie, he had tried to gas himself to death in the garage. Later Bradshaw would claim that he sat in the driver’s seat for an hour, waiting to die, but that nothing happened. He had messed something up. Marc wasn’t sure if his father had really meant to die that day. Was he for real? Was it a play for attention? “Hard to say,” Marc said. “He always claimed he was never depressed and that it wasn’t an issue. He was just tired of life.”

In the three years since, cancer had spread through Bradshaw’s body with a kind of berserk enthusiasm, from his prostate to his lungs and into his bone marrow. At the nursing home where he had once been happy enough—watching TV, eating take-out KFC, flirting with his nurses—he had grown restless, bored, and despairing of the hours before him. When Marc came to visit, he would find his father staring at the wall. Bradshaw’s body began to ache. His bowels cycled between constipation and diarrhea, so that he always felt either stuffed or hollow. Eventually, after a lifetime of refusing to take so much as an aspirin, Bradshaw gave in to the medication protocols recommended by his hospice doctors. He felt less pain on drugs, but he grew loopy and started falling when he got up to pee. His arms sprouted purple bruises and his left leg felt funny all the time. Nurses had trouble picking him up when he fell, and Bradshaw worried about hurting them. He stopped leaving his bed. In May 2018, doctors told Bradshaw that he was nearing the end and that he likely had just two or three months left to live. Marc was in the room and thought he saw his father smile. “People try to help me,” said Bradshaw. “But I think I am done needing help.”

Bradshaw told Marc that he had lived a good life, but that after eighty-nine years, the bad was worse than the good was good. He missed running. He missed fixing up cars. He missed taking his body for granted. “I want to pass,” he said.

“Whoa-kay,” said Marc. And right there, in his father’s little nursing home apartment, Marc took out his phone and Googled “assisted dying + California.” He found a page describing the California End of Life Option Act, which passed in 2015 and which legalized medical aid in dying across the state. It seemed to both men that Bradshaw met the requirements: terminal illness, close to death, mentally competent.

Bradshaw said he had already asked his nurses, twice, about speeding up his death, and that each time the nurses had said that they couldn’t talk about it because it was against their religion. When Marc called VITAS Healthcare—the national hospice chain that managed Bradshaw’s care, dispensing all the nurses and drugs and equipment that Medicare pays for when someone is within six months of death—a social worker explained that while the company respected Bradshaw’s choice, its doctors and staff members would play no part in it. VITAS had prohibited its physicians from prescribing drugs or consulting with patients in aid-indying cases, as had many other hospices in the area, along with the state’s dozens of Catholic hospitals and health systems. On the phone, Marc asked the social worker whom he should call for more information, but the social worker said she wasn’t allowed to help him with that either. (VITAS’s chief medical officer told me later, in an email, that VITAS staff can in fact “discuss and answer any questions on eligibility requirements” and can help refer patients to prescribing physicians.)

It was the hospice chaplain, Marc said, who took him aside and told him to look up Dr. Lonny Shavelson. When Marc searched Lonny’s name, he saw that the doctor ran something called Bay Area End of Life Options. The medical practice was the first of its kind in California, if not the whole country: a one-stop shop that specialized in assisted death. There were articles on the Internet that praised Lonny as a medical pioneer. Unlike other doctors, who prescribed lethal medications for patients to take on their own, Lonny or his nurse was present at every single death; it was part of their standard package, which went beyond the requirements of the law. Other articles, though, were less kind. Some criticized Lonny for running a boutique death clinic. He charged $3,000 and didn’t take insurance, and he didn’t offer refunds if people changed their minds. “Less than you pay for a funeral,” Lonny told me when I asked about his rate.

Marc did some research and found that neither Medicare nor the Department of Veterans Affairs would pay for Bradshaw’s assisted death. Under the 1997 Assisted Suicide Funding Restriction Act, Congress had, with bipartisan support, banned the use of federal funds “for the purpose of causing or assisting in the suicide, euthanasia, or mercy killing of any individual,” a move supported by then president Bill Clinton, who had pledged during his first campaign to oppose death with dignity legislation across the country. Marc didn’t care about the politics. He could pay. He sent an email to the address listed on Lonny’s website: “We would like to enlist your services in this regard.”

Bradshaw formally requested to die on January 9, 2019, starting the clock on California’s mandated fifteen-day waiting period. Afterward, Lonny’s nurse sent over the paperwork. Bradshaw had to sign a state of California form titled “Request for an Aid-in-Dying Drug to End My Life in a Humane and Dignified Manner,” pledging that he was “an adult of sound mind” who was making his request “without reservation, and without being coerced.” Bradshaw told Marc that he wanted to sign his name perfectly—every letter in its proper place—but midway through, his handwriting gave way and looped upward into a wispy scrawl.

It seemed to Lonny that if Bradshaw let the cancer take its course, it would probably kill him in a few weeks’ time. It was hard to say exactly what the death would look like, though it’s possible that he would feel some pain in the end and that hospice nurses would offer him heavy painkillers, probably morphine. On the way out, he might pass through a period of what doctors call “terminal restlessness” or “terminal agitation,” which can induce confusion, disorientation, insomnia, angry outbursts, paranoia, and hallucinations. Some dying people dream that they are underwater and trying hard to swim to the surface to tell you something, but they can’t get there. Many dream of travel. Planes, trains, buses. The metaphors that fill a dying man’s dreamscape can be callow and obvious. For others, delirium is more pleasant; they see angels on the ceilings and the walls. Benzodiazepines could help with the unrest and anxiety. Antipsychotics could ease the visions. Drugged or not, Bradshaw would likely fall into a coma. Maybe he would stay that way or maybe he would dip in and out of consciousness for a while. After a few days or weeks, he would die. The cause of death would technically be dehydration and kidney failure, but the death certificate would recognize his cancer as the underlying killer. Perhaps his children would be at his bedside, but perhaps they would have gone home for the night to get some sleep when Bradshaw took his final breath. Death isn’t always poetic. People die while nurses are adjusting their bodies in bed, to ease pressure off their bedsores. They die when they get up to pee. One hospice nurse told me that men often let go after their wives leave the room for a bite to eat.

The nursing home was painted pale yellow and it looked like a life-size dollhouse, tucked into a street of suburban bungalows in a city called Citrus Heights. The parking lot outside was full, so Lonny pulled into a space next door, which belonged to the Christ Fellowship Church. “We’ll tell them we’re just going to kill someone,” he said brightly as he changed his shoes. Marc was waiting outside, a middle-aged man with a broad frame and black rectangular glasses. He squinted at us, uneasy.

Inside Bradshaw’s room, someone had hung framed photographs on the wall: collages of children and grandchildren, close friends and their grandchildren. There was a certificate thanking Bradshaw for his military service. On the countertop were half-eaten bags of Halloween candy and half-used bottles of hand sanitizer and a plastic cowboy hat—maybe left over from some nursing home theme night. I imagined it sitting atop a nimbler, more alert Bradshaw. “Hi, sweetie,” Cheryl said, sitting at the edge of her father’s bed. She was as slender as her brother was robust, in a peach-colored sweater. “Everyone is here.” Cheryl had flown in from Maryland and Sean had come from Washington State. Marc and Stephanie had driven from nearby and had brought their son. They had all scheduled time off work for the death.

Lonny could see that Bradshaw was a more diminished man than he had been just a few days earlier. When California’s aid-in-dying law passed, opponents imagined that plucky cancer patients would soon be marching into their oncologists’ offices to demand lethal drugs, but that wasn’t what Lonny was seeing. Most of his patients were almost dead by the time they ended their lives; they were weak and a little hazy. Sometimes, this was because their primary doctors had dragged their heels—delaying the process for weeks or months. About a third of people didn’t make it through the state’s required fifteen-day waiting period because they died naturally or lost consciousness, or because they grew too weak to lift a glass of medication to their lips. Or because, when the day arrived, they were too disoriented and confused to fully consent to their own deaths. Bradshaw was teetering on the edge.

Lonny had warned the family that confusion could set in at the end. “Let’s put it this way,” he said, “almost everybody, when they get really close to dying, is demented.” Even so, he had to be convinced that Bradshaw knew what was going on. He didn’t need to know the month of the year or the name of the president, but he had to remember what he was sick with and what he had asked for—and he still had to want it. On a few occasions, Lonny said, he had made it all the way to the bedside and then called off the death because the patient was too out of it to agree to anything at all.

“What are you dying from?” Lonny asked. Then he said it again, louder.

“I’d like to know myself,” Bradshaw said.

“Dad, you have to be serious,” said Marc, and the room fell silent. Cheryl rubbed the back of Bradshaw’s sunken hand, like she was willing his mind to cohere.

I pressed my back into the small partition separating the two sections of the apartment and tried to breathe quietly. From where I stood, I could see into the closet, where a few T-shirts were hanging over a pile of plastic adult diaper packages. I could also see that Bradshaw’s hands were bent inward and that his feet looked swollen and pale, like they were waterlogged. Behind me, his grandson looked down at his phone. Bradshaw said nothing for a while and then recalled that there was something wrong with his prostate.

“OK,” Lonny said, smiling. “We have a bit of paperwork to do.”

Bradshaw groaned. “Oh my God.”

“As you can imagine, the state of California doesn’t let you die easily.” Lonny held up a document. “This little paper here is called the ‘Final Attestation.’ The state of California wants you to sign, to say that you are taking a medication that will make you die.” Bradshaw closed his eyes.

“Dad,” Marc urged. “Dad, you have to stay awake for a few minutes. . . . Daddy, you need to sign, right?”

“Dad,” said Cheryl. “Sign your name.”

Bradshaw opened his eyes and signed the form and Lonny said they were ready to begin. He warned everyone that he didn’t know how long it would take. Some patients died in twenty minutes. Others took twelve hours. He said that he had recently been tweaking his standard drug protocol, adjusting doses and delivery schedules, and that he had managed to lower the average patient dying time to just two hours. Bradshaw would start with an initial medication mixed into apple juice. Then half an hour later he would drink a cocktail of respiratory and cardiac drugs and some fentanyl. The drugs would work to kill Bradshaw in different ways. The respiratory suppressants would likely kick in first, to stop his breathing, but if they didn’t, then the high-dose cardiac medications would eventually stop his heart. Either way, it would feel the same to Bradshaw, who would fall unconscious just a few minutes after taking the final dose. New patients were always asking for “the pill,” Lonny said, but there was no magic death pill. In fact, it was surprisingly hard to kill people quickly and painlessly; the drugs weren’t designed for it and nobody taught you how to do it in medical school.

At the sink, Lonny opened a small lockbox that was filled with $700 worth of medication. I stood beside him and watched him unpack it. He pointed to a green glass bottle. “That’s the fentanyl,” he whispered. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, wasn’t part of the usual drug protocol, but Lonny had added it to the mix to see if it would speed up his patients’ deaths. He had got the idea from a New York Times article about an opioid addict who overdosed after sucking the fentanyl out of some prescription pain patches and letting the solution dissolve in his cheek. “Wow, why can’t we do that?” he had wondered.

Lonny mixed the first powdered drug into a plastic bottle of juice and passed it to Bradshaw, who drank it quickly. Marc exhaled. “You did good,” said Lonny, who noted that the time was noon.

At the bedside, everyone was teasing Bradshaw about the women he was going to kiss in heaven. “I hope he gives all the girls a kiss,” said Sean.

“Well, that’s a given,” said Marc’s wife, Stephanie, who couldn’t stop crying.