11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

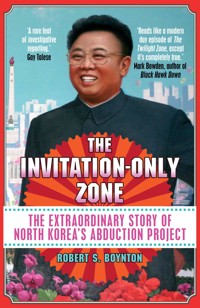

During the 1970s and early 80s, dozens - perhaps hundreds - of Japanese civilians were kidnapped by North Korean commandos and forced to live in 'Invitation Only Zones', high-security detention-centres masked as exclusive areas, on the outskirts of Pyongyang. The objective? To brainwash the abductees with the regime's ideology, and train them to spy on the state's behalf. But the project faltered; when indoctrination failed, the captives were forced to teach North Korean operatives how to pass as Japanese, to help them infiltrate hostile neighbouring nations. For years, the Japanese and North Korean authorities brushed off these disappearances, but in 2002 Kim Jong Il admitted to kidnapping thirteen citizens, returning five of them - the remaining eight were declared dead. In The Invitation Only Zone, Boynton, an investigative journalist, speaks with the abductees, nationalists and diplomats, and crab fishermen, to try and untangle both the kidnappings and the intensely complicated relations between North Korea and Japan. The result is a fierce and fascinating exploration of North Korea's mysterious machinations, and the vexed politics of Northeast Asia.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

In memory ofALICE TYSON BOYNTON(1930–2013)

CONTENTS

Map of Japan and North KoreaKey PeoplePrologue1.Welcome to the Invitation-Only Zone2.The Meiji Moment: Japan Becomes Modern3.Reunited in North Korea4.Japan and Korea’s “Common Origins”5.Adapting to North Korea6.Abduction as Statecraft7.From Emperor Hirohito to Kim Il-sung8.Developing a Cover Story9.The Repatriation Project: From Japan to North Korea10.Neighbors in the Invitation-Only Zone11.Stolen Childhoods: Megumi and Takeshi12.An American in Pyongyang13.Terror in the Air14.Kim’s Golden Eggs15.A Story Too Strange to Believe16.The Great Leader Dies, a Nation Starves17.Negotiating with Mr. X18.Kim and Koizumi in Pyongyang19.Returning Home: From North Korea to Japan20.An Extended Visit21.Abduction, Inc.22.Kaoru Hasuike at HomeEpilogueTime LineNotesSelected BibliographyIndexAcknowledgmentsKEY PEOPLE

Note: Japanese names are rendered first name/last name. Korean names are rendered last name/first name.

SHINZO ABE—Japanese prime minister from 2006 to 2007, 2012 to present

KAZUHIRO ARAKI—chairman of the Investigation Commission on Missing Japanese Probably Related to North Korea

KAYOKO ARIMOTO—mother of Keiko Arimoto

KEIKO ARIMOTO—abducted in 1983 while studying English in London

FUKIE (NÉE HAMAMOTO) CHIMURA—abducted from Obama, Japan, in 1978

YASUSHI CHIMURA—abducted from Obama, Japan, in 1978

CHOI EUN-HEE—South Korean actress and former wife of Shin Sang-ok, abducted from Hong Kong in 1978

KENJI FUJIMOTO—sushi chef who worked for Kim Jong-il, 1988–2001

TAKAKO FUKUI—girlfriend of Japanese Red Army Faction member Takahiro Konishi

TADAAKI HARA—chef abducted from Osaka, Japan, in 1980

KAORU HASUIKE—abducted from Kashiwazaki, Japan, in 1978

KATSUYA HASUIKE—daughter of Kaoru and Yukiko Hasuike

SHIGEYO HASUIKE—son of Kaoru and Yukiko Hasuike

TORU HASUIKE—older brother of Kaoru Hasuike

YUKIKO HASUIKE (NÉE OKUDO)—abducted from Kashiwazaki, Japan, in 1978

KENJI ISHIDAKA—TV Asahi producer, author of Kim Jong-il’s Abduction Command

TORU ISHIOKA—Japanese student abducted from Barcelona in 1980

BRINDA JENKINS—daughter of Charles Robert Jenkins and Hitomi Soga

CHARLES ROBERT JENKINS—U.S. Army sergeant, defected to North Korea in 1965, married abductee Hitomi Soga in 1980

MIKA JENKINS—daughter of Charles Robert Jenkins and Hitomi Soga

KIM EUN-GYONG—daughter of Megumi Yokota and Kim Yong-nam

KIM HYON-HUI—North Korean agent who bombed Korean Air Flight 858 in 1987

KIM IL-SUNG—founder and leader of North Korea from 1948 to 1994

KIM JONG-IL—leader of North Korea from 1994 to 2011

KIM YOUNG-NAM—South Korean abducted in 1978, married Megumi Yokota in 1986

JUNICHIRO KOIZUMI—prime minister of Japan from 2001 to 2006

HARUNORI KOJIMA—abductee activist

TAKAHIRO KONISHI—Japanese Red Army Faction member

EDWARD S. MORSE—American zoologist (1838–1925)

HIROKO SAITO—emigrated from Japan to North Korea, 1963

KATSUMI SATO—director, Modern Korea Institute, abductee activist (1929–2013)

YASUHIRO SHIBATA—Japanese Red Army Faction member

SHIN KWANG-SOO—North Korean secret agent

SHIN SANG-OK—South Korean film director, ex-husband of Choi Eun-hee, abducted from Hong Kong in 1978

HITOMI SOGA—abducted from Sado Island, Japan, 1978

MIYOSHI SOGA—abducted with her daughter, Hitomi, from Sado Island, Japan, 1978

TAKAMARO TAMIYA—leader of the Red Army Faction (1943–1995)

HITOSHI TANAKA—senior Japanese diplomat

TAKESHI TERAKOSHI—abducted from Shikamachi in 1963; currently lives in Pyongyang, North Korea

TOMOE TERAKOSHI—mother of Takeshi Terakoshi

RYUZO TORII—professor of anthropology, Tokyo University (1870–1953)

SHOGORO TSUBOI—professor of anthropology, Tokyo University (1863–1913)

MEGUMI YAO—wife of Yasuhiro Shibata

MEGUMI YOKOTA—thirteen-year-old schoolgirl abducted from Niigata, Japan, in 1977

SAKIE YOKOTA—mother of Megumi Yokota

SHIGERU YOKOTA—father of Megumi Yokota

THE

INVITATION- ONLY ZONE

PROLOGUE

People began disappearing from Japan’s coastal towns and cities in the fall of 1977. A security guard vacationing at a seaside resort two hundred miles northwest of Tokyo vanished in mid-September. In November, a thirteen-year-old girl walking home from badminton practice in the port town of Niigata was last seen eight hundred feet from her family’s front door. The next July two young couples, both on dates, though in different towns on Japan’s northwest coast, disappeared. One couple left behind the car they’d driven to a local make-out spot; the other abandoned the bicycles they’d ridden to the beach.

What few knew at the time was that these people were abducted by an elite unit of North Korean commandos. Japanese were not the only victims, and dozens also disappeared from other parts of Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East during the same period. In May 1978 a Thai woman living in Macau was grabbed on her way to a beauty salon. In July 1978 four Lebanese women were taken from Beirut; later that year, a Romanian artist disappeared, having been promised an exhibition in Asia. Some were lured onto airplanes by the prospect of jobs abroad; others were simply gagged, thrown into bags, and transported by boat to North Korea. Their families spent years searching for the missing, checking mortuaries, hiring private detectives and soothsayers. Only five were ever seen again.

Because the locations they were taken from were dispersed, and their numbers relatively small, almost nobody in Japan drew a connection among the incidents. A local paper slyly described one couple as having been “burned up” by their passion, the implication being that they had eloped after the woman became pregnant. Rumors about the disappearances surfaced periodically, but newspapers reported them as urban myths, akin to alien abductions. When the families of the missing went to the police, they were told that with no evidence of foul play, there was nothing to investigate. After all, thousands of people disappear from Japan every year, the police explained, dying lonely deaths or fleeing drugs, debts, or unhappy relationships. While some members of the Japanese government and police force became aware of the abductions, they avoided acknowledging them officially, which would have required them to take action. And what, after all, could be done? Japan had neither diplomatic relations with North Korea nor a military that could take unilateral action, and its mutual security treaty with the United States wouldn’t be triggered by a handful of kidnappings. And what if a Japanese official raised the issue and North Korea hid the evidence by killing the abductees? “It can’t be helped” (Shikata ga nai) is the phrase the Japanese commonly use to rationalize inaction. So, for the next quarter century, dozens of abductees were fated to languish in North Korea.

1

WELCOME TO THE INVITATION-ONLY ZONE

On the evening of July 13, 1978, Kaoru Hasuike and his girlfriend, Yukiko Okudo, rode bikes to the summer fireworks festival at the Kashiwazaki town beach. The cool night air felt good against their skin as they whisked down the winding lanes of the coastal farming village 140 miles north of Tokyo. They parked their bikes by the public library and made their way past the crowd of spectators to a remote stretch of sand. It was a new moon, and the fire-works looked spectacular against the black sky. As the first plumes rose, Kaoru noticed four men nearby. Cigarette in hand, one of them approached the couple and asked for a light. As Kaoru reached into his pocket, the four attacked, gagging and blindfolding the couple and binding their hands and legs with rubber restraints. “Keep quiet and we won’t hurt you,” one of the assailants promised. Confined to separate canvas sacks, Kaoru and Yukiko were loaded onto an inflatable raft. Peering through the sack’s netting, Kaoru caught a glimpse of the warm, bright lights of Kashiwazaki City fading into the background. An hour later he was transferred to a larger ship idling offshore. The agents forced him to swallow several pills: antibiotics to prevent his injuries from becoming infected, a sedative to put him to sleep, and medicine to relieve seasickness. When he awoke the next evening, he was in Chongjin, North Korea. Yukiko was nowhere in sight, and his captors told Kaoru she had been left behind in Japan.1

Young Kaoru (Jiji Press)

With his fashionably shaggy hair and ready smile, the twenty-year-old Kaoru Hasuike impressed those who met him as a young man who was going places. Like much of his generation in Japan, he wasn’t interested in politics and knew almost nothing about Korea, North or South. Cocky and intelligent, he was at the top of his class at Tokyo’s prestigious Chuo University. Yukiko, twenty-two, the daughter of a local rice farmer, was a beautician for Kanebo, one of Japan’s leading cosmetics companies. She and Kaoru had been dating for a year, and he planned to propose once he finished his law degree. Japan’s economy was surging ahead, and the future looked bright. He’d get a job at a corporation; they’d move from Kashiwazaki to Tokyo and build a life together. That was the plan, anyway.

The overnight train from Chongjin to Pyongyang was extremely bumpy, and by the time Kaoru arrived in the North Korean capital the next morning he was furious. “This is a violation of human rights and international law! You must return me to Japan immediately!” he shouted. His abductor watched calmly as Kaoru vented. When Kaoru saw that confrontation wasn’t working, he tried evoking sympathy. “You have to understand that my parents are in ill health,” he explained. Their condition would worsen if they worried about him. Surely his abductors could understand that?

The abductor listened to Kaoru’s tirade in silence. “You know,” he said, pausing for effect, “if you want to die, this is a good way to do it.” He spoke in the flat, matter-of-fact way of one for whom such encounters were routine. He explained to Kaoru that the reason he had been abducted was to help reunify the Korean Peninsula, the sacred duty of every North Korean citizen. After all the pain his Japanese forefathers had inflicted on Korea, the man continued, it was the least that Kaoru, who had benefited from his country’s rapacious colonial exploits, could do. Precisely how Kaoru would hasten reunification was left ambiguous, although the abductor hinted that he would train spies to pass as Japanese, and perhaps become a spy himself. The good news was that so long as Kaoru worked hard and obediently, he would eventually be returned to Japan.

The abductor saved his most astounding claim for last. Far from suffering from having been abducted, Kaoru would ultimately benefit. “You see, once the peninsula is unified under the command of General Kim Il-sung, a beautiful new era will begin,” he explained. North Korean socialism would spread throughout Asia, including Japan. “And when that glorious day comes, we Koreans will live in peace. And you will return to Japan, where your experiences here will help you secure a position at the very top of the new Japanese regime!” Kaoru couldn’t believe his ears. How could anyone make such preposterous statements?

While North Korea today is one of the poorest, most isolated nations on earth, when Kaoru was abducted in 1978, it was one of the most admired and prosperous Communist regimes in Asia. In 1960 the North’s income per capita was twice that of the South’s. Despite being nearly obliterated by American bombs during the Korean War, the industrial North had enormous advantages over agrarian South Korea, having inherited 75 percent of the peninsula’s coal, phosphate, and iron mines, and 90 percent of its electricity-generating capacity. So equipped, the North’s economy grew by 25 percent per year in the decade following the Korean War.2 In 1975 the North exported 328,000 tons of rice and corn.3 The military dictatorship in South Korea, by comparison, was a basket case, its economy so far behind that its American backers feared it would never catch up. The bitter irony for Kaoru was that 1978 was precisely the year South and North Korea traded places, the former on its way to becoming a global economic powerhouse and the latter beginning its descent into destitution and even famine. In other words, it was the last point in history when the North’s political and economic system was thought to be so self-evidently superior that its spies could snatch people off beaches, show them the glories of the North Korean revolution, and assume they would join the struggle.

Born in 1957, Kaoru Hasuike had a blissfully innocent childhood. Overlooking the Sea of Japan, Kashiwazaki was largely rural farmland at the time, and he and his older brother, Toru, would fish for carp, catfish, and snake heads in the Betsuyama River, which ran behind their house. The brothers were extremely close, and Toru’s advanced knowledge of music and fashion helped Kaoru cultivate an aura of cool, worldly sophistication. An obedient, well-behaved child, Kaoru was captain of the baseball team and a student at the top of his class. Like so many creative, bright students of his generation, he grew more rebellious and bohemian, singing rock music and wearing hole-riddled jeans. In 1974, when Kaoru moved to Tokyo to attend university, the brothers shared an apartment. One day, Kaoru, ever careless, dropped a lit cigarette on a brand-new rug. Without pausing, he simply shifted a flowerpot to cover the smoldering hole. “He shot me that ‘Aren’t I clever?’ look and lit up another cigarette,” says Toru. “Kaoru had it all figured out.”4

Now a captive and with no one to commiserate with, Kaoru was desperately lonely. Although he didn’t have a religious background, he tried praying, placing his palms together and pressing them to his eyes. This display of piety elicited ridicule from his captors, because in North Korean movies the only characters who prayed were the cowardly Japanese prisoners begging for mercy. Not even sleep provided an escape, as Kaoru’s dreams were filled with fantastical versions of his nightmarish days. “I had a recurring dream that some of my friends from back home in Kashiwazaki had been abducted and taken to North Korea, just like me,” he says. “In the dream I’d see them and say, ‘Oh no, they got you too?’”

A few months after arriving in Pyongyang, where he was kept in an apartment, Kaoru realized he was probably stuck there for the foreseeable future, the secretive regime not being in the habit of releasing witnesses to its espionage operations. He was certain that nobody in Japan knew what had happened to him, so he didn’t expect any search parties or diplomatic missions to secure his release. Escape was impossible; three “minders” monitored him twenty-four hours a day, each taking an eight-hour shift. And even if he somehow managed to slip past them, where would he go? It wasn’t as if he could count on receiving help from ordinary North Koreans, who would surely turn him in. The stories he heard about those who had tried to escape weren’t encouraging. The regime had once assigned two military units, three thousand men in all, to capture an abductee who had managed to slip away. Kaoru wondered if he might be able to get help from one of the few Western embassies in Pyongyang. Then he heard about a female detainee who was forcibly removed from an embassy where she had sought asylum—a violation of international law. Kaoru took stock of his options. He was too young to give up on life, no matter how bizarre the circumstances. “As long as I didn’t know the reason for my abduction, or what was going to happen to me, I felt that I couldn’t just die like this,” he says. But how could he survive, cut off from everyone he loved and everything he knew?

Kaoru was given access to a restricted library that held a collection of Japanese-language books about North Korea. Japan’s postwar educational system dealt superficially with the period during which it colonized Korea and much of Asia, so most of what Kaoru was learning was news to him. He was surprised to find out that North Korea had a large following of international sympathizers, many of them in Japan. He read about the wartime exploits of Kim Il-sung’s anti-Japanese insurgency, and the lengths to which ordinary Koreans had gone to resist the Japanese. “After some time, I had to admit that the people of this land had fought bravely against Japanese colonialism. I was able to rationally separate the troubled history of the Korean people from my forceful abduction,” he says.

Over and over, Kaoru’s captors told him he was in North Korea to help right the wrongs of his Japanese colonial forebears. His minders regaled him with accounts of how Japanese soldiers had raped Korean women, dragooned men into slave labor, and generally humiliated Korea’s ancient civilization. “I was horrified by what they told me. I didn’t doubt it was true, but I didn’t know what it had to do with me,” he says. Coming from the quiescent seventies generation of young Japanese, Kaoru had seldom heard history discussed with such vitriol. How had Japanese-Korean relations gotten to the point that, thirty years after the end of World War II, Koreans were so filled with hatred toward the Japanese that they talked about them as if they were a different species? How had the two cultures developed such a twisted relationship?

2

THE MEIJI MOMENT: JAPAN BECOMES MODERN

The problems between Japan and Korea began long before 1910, when the former annexed the latter into its burgeoning empire. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 set Japan on the course to modernize its economy and culture in order to avoid being colonized by the West, and the two themes of modernization (renewing oneself) and colonization (ruling another) were thereafter intertwined. Forty years later, Japan imposed upon Korea the same practices it had adopted. It used the Western pseudoscience of racial classification to legitimize its actions, arguing that Japan and Korea’s ancient racial kinship fated them to reconnect. As non-Western colonizers, the Japanese faced a dilemma: Could a classification scheme that white colonizers had deployed to distinguish themselves from the distant, darker colonized be applied to a nearby and similarly hued people? In other words, could a theory that bound Japan to Korea be construed to justify rule over it? Japan’s answer—a brew of racial reasoning and military power—enabled it to build one of the largest empires of the twentieth century, and has poisoned relations between the two cultures to this day.

Japan had largely closed itself off to the outside world for two hundred years when U.S. Navy commodore Matthew Perry navigated the Susquehanna, a black-hulled steam frigate, into Edo Bay on July 8, 1853. He carried a simple message from President Millard Fillmore: if Japan didn’t open its ports to U.S. merchant ships, Perry would return in a year, with more ships, and take Tokyo by force. In the decade before Perry appeared, the Japanese had watched with growing unease as their neighbors were subjugated by Western powers. With a modest navy and few modern weapons, it realized it had no choice but to accept Perry’s terms. “It is best that we cast our lot with them. One should realize the futility of preventing the onslaught of Western civilization,” argued the scholar Yukichi Fukuzawa in his essay “On Leaving Asia.”

The Meiji era was proclaimed on October 23, 1868, when the fifteen-year-old emperor moved his residence from the Kyoto Imperial Palace to Tokyo (“eastern capital”). Charting a starkly different path from the previous government’s policy of self-imposed isolation, the new imperial government decreed in the Charter Oath that “knowledge shall be sought throughout the world,” and set Japan on the path of studying, emulating, and in many respects surpassing nations around the globe. The Japanese of the early Meiji years were fascinated by the “new,” and would try anything as long as it was different from what came before. “Unless we totally discard everything old and adopt the new,” the novelist Natsume Soseki wrote, “it will be difficult to attain equality with Western countries.” Japan’s first minister of education urged his countrymen to intermarry with Westerners in order to improve Japanese racial stock, and proposed adopting English as the national language.1 Japan built railroads, public schools, and modern hospitals; it established a banking system, a postal network, and a modern military. With the end of the feudal system, people were for the first time free to choose their occupations, rather than follow in their fathers’ footsteps; and new industrial inventions provided many new professions for them to pursue. Children attended free public schools; and as literacy rates soared, so did the number of books and newspapers.

Japan’s fascination with the West was reciprocated. In 1876, eight million people visited the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition to view thirty thousand exhibits from thirty-five nations. The United States showcased George H. Corliss’s steam engine, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, and the Singer sewing machine. Japan’s investment in the exhibition was second only to that of the United States, and included an entire pavilion filled with elaborate bazaars and exquisitely tended gardens. Compared with Japan’s, other countries’ displays looked “commonplace, almost vulgar,” noted The Atlantic Monthly. “The Japanese collection is the first stage for those who are moved chiefly by the love of beauty or novelty in their sight-seeing. The gorgeousness of their specimens is equaled only by their exquisite delicacy.”2 Visitors praised the clean lines and simple elegance of Japanese design. Following the Centennial Exhibition, America went Japan crazy. New Englanders, with their transcendentalist philosophy and love of nature, were particularly smitten. “How marvelously does this world resemble antique Greece—not merely in its legends and in the more joyous phases of its faith, but in all its graces of art and its senses of beauty,” wrote the journalist and Japanophile Lafcadio Hearn.3

Among those attendees who became captivated by the exotic country was Edward Sylvester Morse. A zoologist who specialized in the study of shell-like marine animals known as brachiopods, Morse was spellbound by Commodore Perry’s descriptions in his Journals of the shells he had spotted along Japan’s coastline. On paper, Morse wasn’t the most academic character. Born in Portland, Maine, in 1838, he was a restless boy with the kind of intellectual curiosity and vivid imagination more suited to expeditions than to the classroom.4 When Morse was twelve, his oldest brother, Charles, died of typhoid, and the minister who led the funeral decreed that, not having been baptized, Charles would spend eternity in hell. After his death, their father, a preacher, grew more rigidly religious, denouncing Edward’s passion for science as an affront to God. Morse’s mother, however, was so enraged by the minister’s words that she vowed never again to set foot inside a church. Edward, too, became a rebel, and by the time he was seventeen, he had been expelled from four schools. Although eventually awarded several honorary degrees, he never earned one himself.

Edward Sylvester Morse (Wisconsin Historical Society)

Morse escaped the confines of life in provincial Portland by searching for shells on the Maine coast. Portland had a rich history of trade with destinations all over the world, and sailors regularly returned with strange-looking shells, some of which were sold for vast sums. Morse amassed an enormous collection of native New England specimens, which drew the attention of scholars from around the country. At age seventeen he presented a paper to the Boston Society of Natural History, which named one of his discoveries, Tympanis morsei, after him. Word of Morse’s collection spread to Harvard, where Louis Agassiz held the university’s first chair in geology and zoology. The Swiss-born Agassiz was one of the most famous scientists in the world, having made his reputation by proving that much of the globe was once covered by glaciers. A superb promoter, he convinced New England’s Brahmins to support science and, specifically, to fund the construction of the world’s largest Museum of Comparative Zoology, where he intended to display his specimens. In Morse, Agassiz found a young man with the intelligence and energy to catalogue his vast holdings; in Agassiz, Morse found a father figure who, unlike his own father, encouraged his scientific work. “There is no better man in the world,” Morse wrote of Agassiz in his journal. Paid twenty-five dollars per month, plus room and board, Morse became one of Agassiz’s assistants, an elite group, destined to become some of America’s foremost natural historians and museum directors. A classically educated European, Agassiz was as much their mentor as their employer, inducting them into the modern priesthood of science, while also urging them to study history, literature, and philosophy. Conscious that he was the only one in this group without a college degree, Morse became a diligent student, attending lectures on zoology, paleontology, ichthyology, embryology, and comparative anatomy, while also cataloguing thirty thousand specimens in his first year.

Morse arrived in Cambridge in November 1859, the month Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. A pastor’s son, Agassiz couldn’t bring himself to replace the biblical creation story with the theory of evolution, and became one of Darwin’s foremost critics. Morse read Darwin’s book with excitement but was careful not to antagonize his mentor while he considered the validity of Darwin’s revolutionary ideas. By 1873, however, he had fully embraced Darwin. “My chief care must be to avoid that ‘rigidity of mind’ that prevents one from remodeling his opinions,” he wrote. “There is nothing [more] glorious . . . than the graceful abandoning of one’s position if it be false.” He sent Darwin a paper in which he used his framework to reclassify brachiopods as worms rather than mollusks. “What a wonderful change it is to an old naturalist to have to look at these ‘shells’ as ‘worms,’” Darwin replied.

Having broken with his mentor, Morse left Harvard and discovered he was such an entertaining speaker that he could earn five thousand dollars a year lecturing on popular science. He illustrated his lectures with detailed sketches, drawing with both hands simultaneously, a bit of chalk in each.5 During a San Francisco lecture, he learned that the waters of Japan held dozens of species of brachiopods that were unknown in the United States. In the spring of 1877, Morse boarded the SS City of Tokio.

On the evening of June 18, Morse’s ship moored two miles offshore from Yokohama, and the next day he took a rickety boat to the mainland, rowed by three “immensely strong Japanese” whose “only clothing consisted of a loin cloth,” he wrote in Japan Day by Day. He was overwhelmed by the foreignness of the lively city. “About the only familiar features were the ground under our feet and the warm, bright sunshine,” he wrote. Morse brought a letter of introduction to Dr. David Murray, a Rutgers College professor of mathematics who had been appointed the superintendent of educational affairs for the Japanese Ministry of Education and charged with creating an American-style public school system from grade school through university. Although private academies existed in pre-Meiji Japan, the Sino-centric curriculum was largely restricted to the teachings of Confucius. The Japanese wanted universities comparable to the great institutions that Europe had taken centuries to build, and they wanted them now. The Ministry of Education received a third of the government’s total budget for the project, and Murray was given two years to get Tokyo University up and running.

Foreigners were forbidden from traveling outside Japan’s designated treaty ports, so the only way for Morse to explore for brachiopods was to get special permission, which he hoped Murray would help him with. To reach Murray’s office, he rode the recently completed train line eighteen miles to Tokyo University, which had welcomed its first students three weeks before. As the train approached the village of Omori, it traversed two mounds through which the tracks had been laid. A cockleshell dislodged by the digging caught Morse’s eye. “I had studied too many shell heaps on the coast of Maine not to recognize its character at once,” he wrote. It was a five-thousand-year-old Arca granosa.

Murray introduced Morse to several Japanese colleagues with whom he shared his passion for science. They found his excitement contagious, and made an astounding proposal. Would Morse establish a department of zoology and build a museum of natural history at Tokyo University? In return, they would provide him a biological laboratory, moving expenses, and a professor’s salary of five thousand dollars per year. Darwinism had arrived in Japan during a period of drastic cultural change, and they wanted a Western expert who could explain these foreign ideas.6 Morse was asked to teach a class on modern scientific methods and give a series of public lectures on Darwin. Hundreds attended the lectures, and Morse was pleased both by the enormous size of the audience and by its openness to the idea of evolution. “It was delightful to explain the Darwinian theory without running up against theological prejudice, as I often did at home,” he wrote. Not only were the Japanese not Christians, but the Meiji government was hostile to the creed, which it perceived as a threat to its authority. When Morse argued that “we should not make religion a criterion of investigating the truth of matter,” he no doubt pleased Japan’s bureaucrats and scientists alike.

With Murray’s aid, Morse returned to Omori several weeks later with his students. “I was quite frantic with delight,” he wrote. “We dug with our hands and examined the detritus that had rolled down and got a large collection of unique forms of pottery, three worked bones, and a curious baked-clay tablet.” In order to cross-date the artifacts with ancient flora, fauna, and fossils, Morse and his students used the modern method of digging one layer at a time, a technique that had never been used before in Japan.7 Morse’s book The Shell Mounds of Omori (1879) was the first published by the university’s press.

One of the most profound revolutions inspired by Darwin’s Origin of Species was in the study of early human history, as the notion of “prehistory,” the time before recorded history, led scholars to use physical remains to chart human development from “savagery” to “civilization,” a hierarchy of cultural advancement Darwin later expanded upon in The Descent of Man (1871).8 After Darwin, scholars who had searched far and wide for disparate clues to human development focused their research on chronicling the successive generations who had inhabited a single place, such as Omori. What Morse found at Omori puzzled him. Among the shells and pottery fragments were broken human bones mixed in with those of animals—not what one might find at a typical burial site. “Large fragments of the human femur, humerus, radius, ulna, lower jaw, and parietal bone, were found widely scattered in the heap. These were broken in precisely the same manner as the deer bones, either to get them into the cooking-vessel, or for the purpose of extracting the marrow,” he wrote.9 It was impossible to avoid the conclusion that the people who had once dwelled in Omori had been cannibals. Judging by the age of the bones, Morse didn’t believe the cannibals were direct ancestors of either the Japanese (whom he praised as the “most tranquil and temperate race”) or the indigenous Ainu (who were neither cannibals nor potters). Rather, he concluded, the artifacts had been produced by a pre-Japanese, pre-Ainu tribe of ancient indigenous people.

Morse’s discovery gave birth not only to modern Japanese anthropology but also to the questions that would obsess the discipline for the next seventy-five years: Who were the Japanese people’s original ancestors? Where did they come from? And how were they related to the fast-modernizing Meiji-era Japanese? Much as Western technology gave the Japanese control over their future, Darwin’s theories provided the tools with which to understand their past. Like explorers embarking on an expedition to chart a new world, anthropologists were on a quest to create a modern map of Japanese origins.

Morse’s best student was Shogoro Tsuboi, the twenty-two-year-old son of a prominent doctor. Tsuboi grasped the enormity of the revolution reshaping geology, biology, and the social sciences, and formed a study group that spent weekends excavating near Tokyo University and discussed their findings at evening salons. A cosmopolitan intellectual, Tsuboi studied in London for three years under the great anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor, who used Darwin’s system of classification to divide humanity into racial groups.10 When Tsuboi returned home, he introduced the new discipline to Japan by publishing in popular journals and lecturing widely on anthropology and evolutionary theory.

Ryuzo Torii (second from right) and Shogoro Tsuboi (right)

The Western, biological conception of race did not exist in Japan before this period,11 and Morse’s essay “Traces of an Early Race in Japan” was the first time it was applied to Japan. In pre-Meiji Japan, identity and class distinctions came from the customs, not the blood, one shared with a peer group. For millennia, Asian culture had been dominated by China, and it was believed that a country’s level of civilization was determined by how far it was from the Chinese emperor. Indeed, Korea interpreted its own proximity to China as evidence that it was more civilized than Japan. In the hands of intellectuals such as Tsuboi, race took on a more biological and scientific significance than ever before.

Tsuboi was particularly eager to use historical anthropology to investigate the origins of the Japanese. Employing Darwin’s schema, he reasoned that cultures, like species, develop unevenly, with the vigorous and adaptive jumping ahead and the isolated and recalcitrant lagging behind. He observed that European archaeologists of the day drew analogies between tools produced by Stone Age people and implements used by contemporary aborigines in New Guinea—the implication being that one could detect traces of ancient civilizations in the amber of surviving primitive cultures. If Western scholars could draw direct analogies of this sort, why couldn’t Japanese scholars do so as well? It irked him that Morse, author of the much-resented cannibal hypothesis, was credited as the founder of Japanese anthropology, and going forward Tsuboi felt it should be a strictly Japanese affair. When he became the university’s first full professor of anthropology, he removed Morse’s Omori shell mounds from the museum to make room for “far more valuable specimens” collected by Japanese researchers. Tsuboi envisioned Japanese anthropology as a self-sufficient branch of social science, with Japanese scholars studying the history of the Japanese people in Japan. “Our research materials are placed in our immediate vicinity,” he wrote. “We are living in an anthropological museum.”