11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

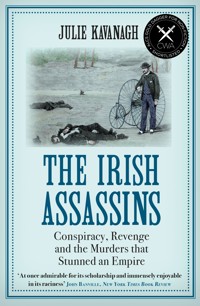

ONE OF THE TIMES' BEST HISTORY BOOKS OF 2021 'The tale of the Phoenix Park murders is not unfamiliar, but Kavanagh recounts it with a great sense of drama... Kavanagh's account reminds me of the very best of true crime.' The Times (Book of the Week) On a sunlit evening in l882, Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Burke, Chief Secretary and Undersecretary for Ireland, were ambushed and stabbed to death while strolling through Phoenix Park in Dublin. The murders were carried out by the Invincibles, a militant faction of republicans armed with specially-made surgeon's blades. They ended what should have been a turning point in Anglo-Irish relations. A new spirit of goodwill had been burgeoning between Prime Minister William Gladstone and Ireland's leader Charles Stewart Parnell, with both men forging in secret a pact to achieve peace and independence in Ireland - with the newly appointed Cavendish, Gladstone's protégé, to play an instrumental role. The impact of the Phoenix Park murders was so cataclysmic that it destroyed the pact, almost brought down the government and set in motion repercussions that would last long into the twentieth century. In a story that spans Donegal, Dublin, London, Paris, New York, Cannes and Cape Town, Julie Kavanagh thrillingly traces the crucial events that came before and after the murders. From the adulterous affair that caused Parnell's downfall to Queen Victoria's prurient obsession with the assassinations and the investigation spearheaded by the 'Irish Sherlock Holmes', culminating in a murder on the high seas, The Irish Assassins brings us intimately into this fascinating story that shaped Irish politics and engulfed an empire. This is an unputdownable book from one of our most 'compulsively readable' (Guardian) writers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for The Irish Assassins

‘A compelling blend of political history and true crime...a colourful, ambitious book...makes most other accounts of the period seem bloodless by comparison’

Sunday Business Post

‘[A] sweeping and compelling narrative of a story that more than bears retelling’

Frank Callanan, Irish Times

‘You could think of this as the prequel to Patrick Radden Keefe’s best seller Say Nothing... Although the events in these two books are set nearly a hundred years apart, they are linked by the push and pull in that country between Protestant and Catholic, between peace and violence, between independence and accord’

Amazon Editors’ Pick

‘This is one of those rare books that is superbly written, tells me something I need to know and which grips the imagination from first word to last. Julie Kavanagh has produced an engrossing account of revolutionary violence, political folly and human weakness. It is a powerful work’

Fergal Keane, BBC correspondent for Ireland

‘[A] page-turning history...This entertaining and richly detailed chronicle offers fresh insights into a conflict whose repercussions are still felt today’

Publishers Weekly

‘In The Irish Assassins, Julie Kavanagh manages the extraordinary feat of guiding the reader through the complexities of Anglo-Irish politics while building the combined tension of an electric political thriller with a tragic love story. The people are real, the events still matter today and the impact is Shakespearean’

Ralph Fiennes

Also by Julie Kavanagh

Secret Muses:

The Life of Frederick Ashton

Rudolf Nureyev:

The Life

The Girl Who Loved Camellias:

The Life and Legend of Marie Duplessis

First published in the United States of America in 2021 by Grove Atlantic

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2022 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Julie Kavanagh, 2021

The moral right of Julie Kavanagh to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 461 9

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 898 3

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For my father

CONTENTS

A Brief History

Before

ONE: The Leader

TWO: That Half-Mad Firebrand

THREE: The “Irish Soup” Thickens

FOUR: Fire Beneath the Ice

FIVE: Captain Moonlight

SIX: The Invincibles

SEVEN: Coercion-in-Cottonwool

EIGHT: Mayday

NINE: Falling Soft

TEN: Mallon’s Manhunt

ELEVEN: Concocting and “Peaching”

TWELVE:Who Is Number One?

THIRTEEN: Marwooded

FOURTEEN: An Abyss of Infamy

FIFTEEN: The Assassin’s Assassin

SIXTEEN: Irresistible Impulse

After

Author’s Note

Bibliography

Endnotes

Acknowledgments

Index

A BRIEF HISTORY

EVERY READER of this book will know about the age-old hostility between the Irish and the English, but not everyone will know how, when, and where it started. It was in 1170, to be precise, that Anglo-Normans first invaded Ireland, going on to grab the best land and introduce their own feudal system—a hierarchy of master and serf, landlord and tenant that was still in place more than seven hundred years later. Since then, the theme of violence between the two places—erupting, receding, erupting again—has never entirely disappeared. The muraled “peace walls” separating Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods in Northern Irish cities like Belfast and Derry had been prefigured in the fourteenth century by the thorny hedges and ten-foot ditches bounding “The Pale,” an area covering Dublin and its surroundings, under protection of the Crown and governed by its rules. It was considered to be a pocket of safety and civilization in marked contrast to the barbarous conditions of Irish life outside (and is the origin of the expression “beyond the pale”).

This “Us and Them” divide, “their religion” or “our religion,” intensified during the Reformation, when Protestantism replaced Roman Catholicism as the national church in England and Ireland, and Irish Catholics were seen as dangerous worshippers of the anti-faith. Henry VIII had broken ties with Rome when the pope refused to annul his first marriage and made himself supreme head of the English Church. He was also named king of Ireland, but his daughter, Queen Elizabeth, took much firmer control of their neighboring island. Fearing that her enemy—the Spanish Catholic King Philip—would use Ireland as a foothold to launch an attack on England, she decided to populate the country with loyal subjects. This involved confiscating vast quantities of land from powerful Gaelic families in the province of Munster and planting Irish estates with English and Scottish settlers.

One of the first arrivals was the great Elizabethan poet Edmund Spenser. Appointed a colonial official, he was a party to what was literally a war of extermination by the English—the 1580 suppression of a rebellion against the queen in Munster. More than six hundred Spanish and Irish soldiers were massacred; ordinary people systematically butchered; Catholic priests, hanged until “half dead,” were then decapitated, their heads fixed on poles in public places to instill fear in the native inhabitants. “So the name of an Inglysh man was made more terrible now to them than the sight of an hundryth was before,” remarked Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the queen’s ruthless military governor. The appalling famine that resulted from the merciless destruction of crops and cattle by Elizabeth’s troops left an estimated thirty thousand inhabitants dying of starvation—“anatomies of death,” who crawled along the ground because their legs were too weak to support them and feasted on carrion and carcasses they had dug out of graves. Spenser was one of the queen’s most ardent devotees, and his masterpiece, the allegorical epic The Faerie Queene, an extravagant homage to her sovereignty. And yet, his horror of what he saw in Munster is embedded in his writing: the hollow-eyed character of Despair wearing rags held together with thorns, his “raw-bone cheeks . . . shrunk into his jaws,” is the very image of the Irish famine victim.

It was as if the English felt themselves absolved from all ethical restraints when dealing with the Irish. The divine right of kings legitimized the use of force in maintaining the dominion of the sovereign, and as the insurrections of the Irish amounted to treason, Englishmen had God’s sanction to keep the rebellious natives in their thrall. Right of conquest had also validated England’s confiscation of Irish land.

*

Ultimately, in 1641, the long-suppressed Irish retaliated with a wave of horrific attacks. Queen Elizabeth’s successor, James I, had followed her policy of planting Irish estates with English and Scottish settlers and was concentrating on Ulster, the center of residual Gaelic resistance. Native resentment erupted: a County Armagh widow was captured by insurgents, who drowned five of her six children; in Portadown, one hundred English Protestants were herded from the sanctuary of a church, marched to a bridge over the River Bann, and forced into the wintry waters, where they died of exposure, drowned, or were shot by musket fire. As always, though, Britain, with its far superior military resources, had the upper hand. Retaliation for the 1641 uprising, and the reconquest of Ireland (which, following the English Civil Wars, had become the monarchy’s last chance of retaining the throne), resulted in one of the most shocking war crimes ever recorded.

In August 1649, six months after the execution of King Charles I, the parliamentarian General Oliver Cromwell decided to crush any remaining Royalist loyalty among Irish Catholics by conducting a massive campaign of ethnic cleansing. During his nine-month rampage, six hundred thousand perished, including fifteen hundred deliberately targeted civilians. Landowners, given the choice of going “to hell or to Connaught,” were forcibly driven west to the bleakest and poorest of the provinces, where they were allowed 10 percent of their original acreage. And yet, the vast majority of Cromwell’s contemporaries applauded his ruthless mission. To Irish Protestants, he was a brave deliverer who put down popery and set them free, while the celebrated English poet and parliamentarian Andrew Marvell endorsed Cromwell’s view of himself as a divine agent, regarding him as an elemental firebrand who could not have been held back. “’Tis madness to resist or blame / The force of angry Heaven’s flame,” he wrote, in “An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s Return from Ireland.”

No other figure in nine centuries of Anglo-Irish history has so starkly embodied the divide between the two nations: Ireland’s view of Cromwell as a monstrous tyrant is countered by England’s admiration of the soldier and statesman—today considered “one of the ten greatest Britons of all time”—who steered his country toward a constitutional government. A 1946 spy film, I See a Dark Stranger, gently satirizes this polarity, pairing the naïvely romantic Irish heroine (a dewy Deborah Kerr) with a British army type (Trevor Howard). He is writing a thesis in his spare time on Cromwell, explaining that the “underrated general” is a highly neglected character. “Huh! Not in Ireland!” snorts Kerr’s Bridie Quilty. “Do you know what he did to us?” Her private war against Britain has been provoked by hearing Guinness-fueled tales of Cromwell’s terrible deeds, and although she ends up marrying the Englishman, she still retains her fierce nationalist principles. On the first night of their honeymoon she storms off with her suitcase after spotting the inn sign beneath their window: “The Cromwell Arms.” Fifty years later, in much the same spirit, Irish prime minister Bertie Ahern is said to have marched out of the British foreign secretary’s office, refusing to return until a painting of “that murdering bastard” had been removed. (It was a political gaffe likened to “hanging a portrait of Eichmann before the visit of the Israeli Prime Minister.”)

*

Accounts of appalling suffering have been handed down from generation to generation, mythologized in folklore, poems, and patriotic songs. It was this historical grievance against the English—the “taunting, long-memory, back-dated, we-shall-not-forget . . . not letting bygones be bygones”—that Tony Blair decided to address when he was elected prime minister in 1997. The year marked the 150th anniversary of the Great Famine, when Ireland lost two million of its population through death or emigration—the most cataclysmic chapter of its history. The Irish had always blamed the disaster on Britain, which in the interest of protecting its economy, continued to import food from Ireland when its population were starving. Blair conceded that his country had indeed been accountable. In a message of reconciliation, read at a memorial concert by the actor Gabriel Byrne, he said, “That one million people should have died in what was then part of the richest and most powerful nation in the world is something that still causes pain. Those who governed in London at the time failed their people through standing by while a crop failure turned into a massive human tragedy.” Hailed as a landmark in Anglo-Irish relations, Blair’s admission coincided with a breakthrough in the Irish peace process—a few weeks later, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) restored its cease-fire.

*

The Great Famine had begun in 1845, when a virulent fungus, Phytophthora infestans, migrated from America to the potato fields of Ireland, Britain, and Europe, reducing entire crops to a black stinking mush. Nineteenth-century science had no remedies for such epidemic infestations, and as potatoes were the staple diet for at least half the people, the impact of the crop’s massive failure was more catastrophic in Ireland than anywhere else. “The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine,” was a typical nationalist response at the time, the accusation being that the apathy of English politicians, combined with their laissez-faire economic doctrine, had decimated the Irish peasantry. Even more incriminating was the belief that their campaign had been deliberate. The minister in charge of charitable relief, Charles Trevelyan, was demonized by the twentieth century, his much-quoted remark that “God had sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson” used as evidence by conspiracy theorists. In 1996, New York governor George Pataki ordered the Irish Famine to be included in the state’s school curriculum, saying that children were to be taught that hunger had been used by Britain as a tool of subjection, “as a means of keeping people down.” The Irish Famine/ Genocide Committee, founded in the United States a year earlier, looked into the possibility of forming an international tribunal to rule on legal accountability for the human loss.

Ordinary people’s resentment was directed not so much at the British government as at local agents, land-grabbers, and moneylenders—the avaricious “gombeen men,” who exploited the situation to their own advantage. What can be in no doubt, however, is the culpability of many Irish landlords. Regarding the removal of the poor from their estates as a prerequisite to making agricultural improvements, they used the Famine as an opportunity for mass clearances, evicting an estimated quarter of a million people. With nowhere to go, desperate tenant families built temporary shelters near their former homes, only to have them burned down or destroyed by bailiffs and hired crowbar brigades emboldened by the support of police and soldiers. In March 1846, responding in Parliament to complaints of inhumanity, the home secretary sided with the landlords, rejecting the notion that they were liable for criminal proceedings: as property owners, each had the right to do as he pleased.

*

In post-Famine Ireland, most smallholders were in arrears with their rent, and while numerous employers went out of their way to treat their workers with compassion—“Feed your family first, then give me what you can afford when times get better,” said one Bantry-based man—landlords continued to be much despised. The most prominent were often absent from their properties, the MPs in London while Parliament sat, the wealthiest moving between their various estates and delegating the management to land agents, who notoriously exploited their power over the tenants. Less prosperous owners did not have the cash to invest in improvements, and consequently, the country’s farming methods had stagnated. The umbrella term for the situation was “landlordism,” an entirely pejorative word implying abuse of authority, from rack-renting to mercilessly arbitrary evictions.

And then, in the late 1870s, when rural Ireland—especially the west—was again threatened with starvation and eviction, a radical change took place. Determined never again to make “a holocaust” of themselves, smallholders began collectively rising up and fighting for ancestral territory that was theirs by right. The Land War of 1879–82 became the greatest mass movement Ireland had ever known, a social revolution led by a messianic land activist and an inspirational new political leader whose mission to bring down feudalism was funded by what today would be millions of American dollars. For the first time in seven hundred years, Irish tenant farmers stood together to destroy the landlord system, mounting an anarchic campaign of intimidation, which the British tried to suppress with hateful new coercive measures.

By the beginning of the 1880s, the Irish land issue had reached a crisis point, occupying an astonishing nine-tenths of Britain’s political agenda. What is less known is that the first rumblings of resistance took place more than two decades earlier—not in Dublin, the hub of revolutionary fervor, but in a wild, wind-battered corner of County Donegal, in Ireland’s northwest.

BEFORE

ALL ALONG Donegal’s Bloody Foreland, the Atlantic surf was seething and hurling itself against the rocks. It was the winter of 1857, and most of the inhabitants were down on the shore—men, women, and children, braving the gale to scythe seaweed from the shingles or wade into the foaming brine to gather it in armfuls. Draping the granite boulders with slimy, reddish-brown matting, these tangles of kelp were a commodity valuable enough for the locals to risk their lives in every storm. As the breakers boomed around them, sucking up seaweed from the deep, the families went out in force to collect it—soaked to the bone and aching with windchill and exhaustion.

Less than ten miles away, in the warm glow of a gaslit, mahoganypaneled room, a Belfast journalist was enjoying a glass of punch served by a fetching young barmaid. The door opened, and Lord George Hill, the owner of the Gweedore Hotel, looked inside to ask whether there was anything he could do to make the guest more comfortable. A convivial host, Hill had opened the hotel sixteen years earlier, modeling it on a Scottish Highlands lodge to provide salmon fishing and grouse shooting for the gentry. He had been enchanted by the vast open spaces, lakes, rivers, dramatic mountains, and savage seas of Gweedore, a small Roman Catholic community in northwest Donegal, and had bought land comprising twenty-four thousand acres, intending to create a kind of oasis there. The hotel he opened offered English tourists a pampering but adventurous alternative to Cheltenham’s Promenade or the Pump Room in Bath, and with the arrival of guests as eminent as the Scottish historian and writer Thomas Carlyle, Hill could claim to be bringing metropolitan manners and culture to a place that had long been cut off from the world outside.

Situated in the northern province of Ulster—the most Protestant part of Ireland—and geographically distant from the rest of the Republic, Donegal has a unique spirit of independence. The parish of Gweedore, located in the heart of the Gaeltacht, where Irish is still the first language, is even more distinctive. It has none of the soft pastoral lushness of the south but is a remote area of blanket bog and primeval rocks, with a harsh, architectural beauty of its own. For centuries, its people had clung to the coast, struggling to make a living from land not meant to be worked, many of them living in mud hovels shared with a farm animal. Potatoes were their regular diet, and their main source of income was kelp, which they burned in kilns until the ashes could be compressed into hard blocks to be shipped to Scotland, where they were used to make iodine. Some traded in woolen goods, eggs, and corn (much of which was distilled into the illegal whiskey poteen), and it was this small local industry that Lord Hill decided to expand on a massive scale.

On the twenty-five hundred families who lived on his land, Hill launched what he called “a curious social experiment.” He found overseas buyers for Gweedore’s seafood, poultry, dairy products, and knitwear, commissioning a London firm to purchase homespun goods. He created a model farm, employing an agriculturist to introduce new methods, and miraculously reclaimed acres of spongy bog and impermeable granite to cultivate a number of different crops. He improved the roads, constructed a harbor, built bridges and mills for flax, wood, and corn, set up an icehouse to store the fish, opened a bakery, a tavern, a schoolhouse, and a general store. Not only involved with the running of the estate on a daily basis, Hill had learned enough Irish to speak to his tenants in their own language—an extraordinary departure in the context of the times. Unlike the malign stereotype, Lord Hill was a landlord of outstanding benevolence and vision. Or so it first appeared.

The Great Famine had been felt most desperately in the west (where there were even reports of cannibalism), and with ruin affecting countless estate owners, the more entrepreneurial among them had begun seeking ways to increase their revenue. One of Hill’s first innovations was to reorganize his Gweedore acreage. Until then, under an ancient form of property division known as “rundale,” arable land was held in joint tenancy by all its occupiers, who lived in clusters of houses with no fences separating their plots. It was a communistic arrangement that inevitably led to disputes, but it also forged a strong sense of solidarity. To Hill, these old ways were a barrier to any progress. He gave each smallholder his own strip of land and ordered him to demolish his house and construct a new one. This caused tremendous discontent. Not only were people asked to pay four times more rent for these rectangular “cuts,” but they were expected to build the new houses at their own expense. Worse was to come.

Seeing the commercial potential, Hill imported large numbers of Scottish sheep, accompanied by their foreign owners, to graze on his mountain pastures. Tenants whose animals previously had access to land used by their ancestors for centuries now found themselves either charged a fee for entry or fined for straying stock. This provoked the Gweedore Sheep Wars—a campaign of furious retaliation in which hundreds of imported livestock were stolen, killed, or brutally maimed.

Hill’s neighbor, a wealthy land speculator named John “Black Jack” Adair, followed his lead. Owner of the stunningly beautiful land around Lough Veagh, Adair rearranged its boundaries for the grazing of imported sheep, and in November 1860, his Scottish land steward was found beaten to death on the mountain. Holding his tenants collectively responsible, Adair decided to exact revenge. Over three days in April 1861, around two hundred rifle-carrying constables, soldiers with bayonets, and a hired crowbar brigade descended on the district. Declaring that they had legal hold, the men forced their way into every cottage and drove whole families onto the road. An entire community of 244 people was left at the mercy of relatives, friends, or the poorhouse, their possessions buried under the demolished walls and thatch of their homes. Although news of the scandal was raised in Parliament, no action was taken because Adair had broken no law. “The Crown could pardon a murderer, but could not prevent an eviction.”

In the winter of 1857, the Adair evictions were still to come, but already the landlord-tenant conflict was alarming enough to have brought the editor of the Ulsterman, Denis Holland, to Gweedore to see things for himself. His guide would be Father John Doherty, an ardent defender of tenants’ rights who had played a critical role in the sheep war by encouraging his parishioners in their anti-grazier revolt. Lately, however, the priest had decided that a more effective form of activism would be a newspaper propaganda campaign led by journalists like Holland, who were sympathetic to the cause, and could help to discredit Donegal’s despotic landlords.

*

The gale had lost none of its force when the two men, priest and journalist, set off in the morning, the sleet lashing their faces with the viciousness of a knotted cord. As they drove away from the hotel, Holland noted the picturesque cottages nearby, learning they were not inhabited by smallholders but were show homes, rented to local bureaucrats—the first sign that Hill’s philanthropy might be something of a facade. Farther afield, on the wild mountain road to Derrybeg, they passed the straight furrows of the new cuts, which Father Doherty declared to be evidence of Hill’s self-promoting destruction of the community—“a means of generating pauperism.” Here and there, scarcely distinguishable from the boulder-strewn bogland, was a stray cabin of peat sod or unmortared stone. Stopping to inspect one, they entered a single, sunken chamber and found a ragged man sitting by the fire with a sickly toddler in his arms, another child lying on a mound of turf. Simmering in a hanging pot was a brew of seaweed and foul-smelling liquid, and behind a screen, there was a mountain cow. The only furniture was a pine table and a bundle of rags in a corner serving as a couch in the day and a bed at night. Every dwelling they visited during the tour was just as abominably wretched.

Father Doherty was eager for Holland to talk to an angry tenant farmer who had been radicalized after spending seven or eight years in the United States. They headed north to the hamlet of Meenacladdy, where the rocky mountain road comes to an end. With its bleak stony beach overlooking Tory Island, and with the haunting, ashen cone of Errigal Mountain to the east, Meenacladdy was then—and still is—a place out of time. Michael Art O’Donnell and his wife, Margaret, had settled in the parish in the mid-1830s to build a house and start a family. Their first son, Patrick, was born around 1838. Daniel followed three years later, and they also had two daughters, Mary and Nancy. All went well, with O’Donnell cultivating his arable patch, until 1844, when a Dublin solicitor and property speculator, Lord John Obin Woodhouse, bought up Meenacladdy’s thousand acres, taking away the tenants’ grazing rights and sectioning off the land. “We got it out of rundale with great difficulty,” Woodhouse would later remark. “The people were so much opposed to it.”

For Michael Art O’Donnell, not being able to subdivide his property meant not providing a legacy for his sons, and he decided to emigrate. Selling his leasehold to Woodhouse’s manager for twenty pounds, he paid his way to America, settling with his family in Janesville, Pennsylvania. They were away for the Famine years and doing fairly well in the States, but a yearning for home brought them back to Meenacladdy in the mid-1850s. O’Donnell repurchased his “tenant right” to the land, only to discover that Woodhouse had quadrupled the rent, justifying this by the amount of money he had spent on improvements in the interim. “Sure if it wasn’t for burning the kelp we couldn’t pay the rent at all,” exclaimed O’Donnell. “An’ even on that the landlords want to put a tax if they can.” He uttered some angry words in Irish, which to Holland sounded like oaths, surprising him, as he’d encountered only crushed acquiescence until now. Father Doherty smiled. “I fear Mihil learned to curse a little in America,” he said.

It was hard for an outsider to understand what could have driven Michael Art O’Donnell back to the hardships of Donegal and its implacable landlord rule. His explanation was simple. He and his wife had been disturbed by the “immorality” they had seen in the States and became increasingly frightened that their children would “lose their religion.” Anti-Catholic forces in 1850s America were stronger than at any other time in its history, with roving street preachers zealously working to convert new immigrants to Protestantism. It was a decade in which enemies of Catholicism far outnumbered the Catholics themselves; churches were violated by fanatics who whipped up hatred and hysteria about “a bigoted, a persecuting and a superstitious religion.” And with most impoverished Irish immigrants gravitating toward the tenement districts of American cities, alcoholism and crime were rife. “Better for many of our people they were never born than to have emigrated from the ‘sainted isle of old’ to become murderers, robbers, swindlers and prostitutes here,” one Boston Irishman exclaimed.

So, the O’Donnells were far from alone in believing that the option of one meal a day of potatoes and seaweed in Ireland was better than the sinful temptations of American urban life. And yet, they must have known that Meenacladdy could offer their sons no future. None of the four siblings was able to read or write; the two girls could marry, but with hundreds of families in the region facing destitution, what prospects were there for the boys?

Between 1858 and 1860 hundreds of single young people began leaving Gweedore and the adjoining parish of Cloughaneely, carrying tufts of grass or lumps of turf as mementos of their homeland. The departure ritual was always the same. The night before, there would be drinking, singing, and dancing, but when daylight broke the caoine (keening) would start in earnest, its eerie sound fading as the young emigrant left the village, watched by family and friends until he or she could no longer be seen.

Sponsored by a relief fund, the teenage Dan O’Donnell emigrated to Australia; Paddy went to America—“the New Ireland across the sea”—just one of millions of anonymous immigrants driven to seek a better future. Or, at least, so he was until the name Patrick O’Donnell became infamous throughout the world—a name that still resonates in Donegal to this day.

ONE

The Leader

Twenty years later

FROM WELL before dawn on a rainy Sunday in June 1879, tenant farmers from miles around began converging on the coastal town of Westport in County Mayo. By mid-morning a procession had formed of men wearing green scarfs patterned with the Irish harp and shamrock and brandishing banners with the words ireland for the irish! serfs no longer! the land for the people! A brass band accompanied them as they made their way in a heavy downpour to a field near the town, where a crowd of about eight thousand had gathered. Taking the platform, the chairman introduced the first speaker as “the great Grattan of this age,” shrewdly predicting that, like Henry Grattan, the pioneering statesman who won new legislative freedom for Ireland in 1782, this was another Irish Protestant who would leave his mark on history.

We have here amongst us today Charles Stewart Parnell [cheers] whose high character is well known to all of you [cheers]. He left the county of Wicklow yesterday to be here today [He is welcome!] and he will leave Westport tonight to be in the British Parliament tomorrow night [cheers and a shout, “And a good man he is in it!”].

A slim, proud, inscrutable figure with fire in his eyes, Parnell had all the authority of a natural ruler, and yet, unlike the electrifying Grattan, he was no orator. His speech was plain, his voice quite soft, but his clenched fists conveyed the anger he felt about Ireland’s feudalism as forcefully as eloquent words.

You must show the landlords that you intend to hold a firm grip of your homesteads and lands [applause]. You must not allow yourselves to be dispossessed, as you were dispossessed in 1847. . . . Above all things remember that God helps him who helps himself, and that by showing such a public spirit as you have shown here today, by coming in your thousands in the face of every difficulty, you will do more to show the landlords the necessity of dealing justly with you than if you had 150 Irish members in the House of Commons [applause].

Five years earlier, Parnell could not have held this audience. He was a landlord himself, the owner of Avondale, a family estate in softly rolling County Wicklow, and never happier than when riding, hunting, shooting, or playing cricket. Three of his ancestors had been distinguished politicians, his American mother voiced blazing anti-British views, and two of his sisters were militant nationalists, but Charles did not know or care about Anglo-Irish affairs—in fact, with his aloof manner and Oxbridge accent he could easily be mistaken for an Englishman. His priority throughout his twenties had been to turn his five-thousandacre property into a paying proposition and become a progressive landowner while maintaining good relations with his tenants. If he ever set foot in Avondale’s well-stocked library, it was not to consult the texts on vital Irish issues written by his grandfather and great-uncle but to expand his own interests—geology, mining, mechanics, and country sports. The only book his favorite brother ever saw him read was William Youatt’s History, Treatment and Diseases of the Horse.

*

Sir John Parnell, Charles’s great-grandfather, a passionate supporter of Irish independence, had been a member of Grattan’s Parliament but forfeited his post as chancellor of the exchequer when he opposed the merging of Ireland with England—the 1801 Act of Union that brought Irish administration under the control of West-minster. Sir John had not engaged with the cause of Catholic political emancipation—the right to sit in Parliament—but his two sons, Henry and William, both parliamentarians, had thrown themselves into the fight (finally won in 1829 by the legendary Irish leader Daniel O’Connell).

Henry’s book on the penal laws chronicling England’s legal persecution of Irish Catholics during the eighteenth century is regarded as a classic, while William’s pamphlet An Historical Apology for the Irish Catholics was reprinted at least three times. In it, Queen Elizabeth is reviled as an oppressive and vindictive tyrant whose bigotry toward Catholics and confiscation of Irish land was the main cause of the country’s lasting discord. William’s only fictional work, Maurice and Berghetta; or, The Priest of Rahery: A Tale, is dedicated to the Catholic priesthood, and what the novel lacks in human interest is made up for in the “aching pity” of the introduction. A cry from the heart, it inveighs against the deplorable state of the Irish peasantry—a people degraded, oppressed, and forbidden any connection with the civil business of their country—and pleads for compassion from the Anglo-Irish class: “The unfeeling society in whose narrow circle they pass their time; they eat pineapples, drink champagne, shoot woodcocks, are assiduously flattered and feeling themselves very well off, forget how other people suffer.”

It was William Parnell, Charles’s grandfather, who inherited Avondale from a cousin and combined his role of country gentleman with that of politician and proselytizer—“Constantly thinking, studying, writing, talking in hope that by exertion or good fortune he might be the means of bettering [Ireland’s] condition.” His son, John Henry, Charles’s father, while also free of the usual supremacist attitudes, did not involve himself in anything other than parochial administrative affairs. He aimed simply to be a liberal and innovative landlord of Avondale and his two other Irish properties, relishing local society, proud of his position as master of the hounds, and indulging his great passion for cricket. But on a tour of the United States and Mexico, his eyes were opened to the world beyond Wicklow—an adventure that led to “the one impetuous act on the part of a generally sober and predictable young man.” This was his heady marriage in 1835 to a vivacious Washington belle, whom John Henry brought back to live with him at Avondale.

Nineteen-year-old Delia Stewart, the daughter of Admiral Charles Stewart, famous for his naval victories against Britain in 1812, can only have been impressed by the beauty of Avondale’s surroundings—the magnificent park and woodlands sloping down to a deep gorge in the winding River Avon. The house itself was comfortable, if not particularly grand, with the bleak facade common to Irish Georgian architecture—a bleakness that worsened in the incessant rain. Before long, John Henry’s new bride was feeling melancholy and isolated; she was “a flaring exotic,” accustomed to far greater freedom than young women of the Irish gentry were. Not sharing her husband’s interest in country sports, and bored by his circle, she began spending more and more time in Paris with her brother, whose Champs-Élysées apartment was a social hub of the American colony. Inevitably, the Parnells grew apart, although their marital relations must have continued, as Delia gave birth to twelve babies before the age of thirty-six (two did not survive).

Born in 1846, one of four brothers and six sisters, Charles was regarded as the household pet, his every whim indulged. He was delicate in health yet headstrong in manner, bullying his sisters and domineering even his brother John, who was four years older, mercilessly imitating his stammer so often that he started stammering himself. John and their younger sister Fanny were his constant companions, much closer to him than anyone outside the family, apart from his nurse, a firm but affectionate Englishwoman known as Mrs. Twopenny (pronounced “Tup’ny”). In line with upper-class custom of the time, Charles was sent to boarding school at the age of six or seven. With Delia mostly absent from Avondale, John Henry—wanting to find a kindly surrogate, someone “who would mother [Charles] and cure his stammering”—enlisted the help of the principal of a girls’ school in Somerset. When Charles contracted typhoid fever during his second term, she devotedly nursed her small charge back to health, but then felt it her duty to send him home. Over the next few years, he was tutored mostly at Avondale, and when his father died unexpectedly in 1859, Delia stepped in to supervise the education of the two older boys in preparation for university.

John, who was being schooled in Paris, accompanied thirteen-yearold Charles to a private cramming academy in the Cotswolds, whose regimentation contrasted harshly with their comfortable, if haphazard home life. To the masters, Charles was a reserved, edgy boy, while his fellow pupils disliked him for his arrogance and aggressiveness. Only while riding, hunting, or playing cricket did he distinguish himself, although John enviously noted that “Charley’s” adroitness on the dance floor had made him quite a catch among the local girls. Seemingly untroubled by remaining in his younger brother’s shadow, John was a kind, self-effacing youth who was nevertheless prone to occasional eruptions of the Parnell temper. Of the two, only Charles appears to have inherited elements of a much darker ancestral strain: he suffered all his life from melancholia, anxiety, sleep-walking, and night terrors that would cause him to “spring up panic-stricken out of deep sleep and try to beat off an imaginary foe.” But he would be spared the mental disintegration of two forebears—Thomas Parnell, an eighteenth-century clergyman and minor poet afflicted with manic depression, and their great-uncle Henry Parnell, whose depression spiraled into psychosis and suicide.

*

The 1860s saw the rise of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret movement formed in Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day, 1858, with the aim of overthrowing British rule by armed insurrection. In homage to the Fianna warriors of Irish mythology, the IRB’s oath-bound members became known as “Fenians,” and their crusade expanded so fast that they decided to launch a newspaper as a mouthpiece—the Irish People. Fanny Parnell, the family bluestocking, a petite, dark-haired sixteen-year-old, was swept up by this new wave of nationalism and began contributing passionately patriotic poems. Charles disapproved, refusing to accompany his sister to the paper’s offices—“the Fenian stronghold”—and making fun of her verses, just as he chided their mother for her gullible support of members of the movement, whom he suspected were vagrants, turning up at the door for handouts. “He distinctly resented the idea of being stamped as a Fenian,” John remarked, “[and] finally declared that he would leave the house if anything more was said about the Fenians.”

As it happened, Charles was not in Dublin during a frenzy of Fenianism in the fall of 1865. The British government had suppressed the Irish People and arrested its editors for high treason; Fanny and John attended every day of their trial, and the Parnell house in Temple Street was searched by police, whose suspicions had been alerted by Delia’s flamboyant complicity with the rebel cause. Charles had just started his first term at Cambridge, having been accepted by Magdalene College, a small, sporty establishment whose undergraduates were mostly rowing hearties, “sons of monied parvenus from the North of England.” He made himself unpopular from the start, disdaining student antics and furiously throwing out a group who burst into his room to carry out some prank. The teaching at Magdalene was as lax as its admissions standards, but that suited Charles, who had no academic ambitions and was described by one contemporary as “keen about nothing.”

His real education took place during university vacations. He had inherited Avondale on coming of age (John was left an estate in County Armagh), which brought him close to tenant farmers and deepened his attachment to the Irish land. He loved to spend time at a rough mountain shooting lodge, a former military barracks used to house troops involved in the suppression of the 1798 uprising. Drawing inspiration from the revolutions in France and America, this bloody fight for independence, lasting a few concentrated weeks, had disastrously rebounded, leading to the abolition of the Dublinbased Irish Parliament and opening the way for the union of the two nations. Britain’s savage crushing of the insurrection was entrenched in Irish memory, and Charles would have heard tales from his old retainers of rebel soldiers ruthlessly tortured and executed (there were at least ten thousand Irish fatalities to England’s six hundred). He is said to have taken pride in the tattered Irish Volunteer banner hanging in Avondale’s baronial hall—relic of the Grattanite movement of the 1770s and ’80s pushing for increased Irish autonomy. But it was a contemporary incident, not the discovery of history close to home, that triggered Parnell’s political awakening.

In February 1867, as preparation for a nationwide revolution, there was an abortive Fenian raid on the armory wing of England’s Chester Castle, and once again, the rising was suppressed by the British. The perpetrators were deported or imprisoned without trial, and during a Fenian ambush in Manchester to free two comrades from a police van, an officer was killed. What had been just an accident unleashed a wave of anti-Irish hysteria in England, leading to a notoriously prejudiced trial, and in November, three Irishmen—not one had fired the fatal shot—were hanged in front of at least a thousand spectators. The British government’s execution of the “Manchester Martyrs” touched off a global outpouring of protest, the ferocity of which shook Parnell into engaging with Irish history for the first time. “Driven wild” by the injustice of inflicting the death penalty on men who had not committed willful murder, he began to learn of seven centuries of Irish victimization, and what had previously been no more than a faint Anglophobia—an aversion to that almost tangible sense of superiority and entitlement in the English character—intensified into an obsession.

“These English despise us because we are Irish,” he told John. “But we must stand up to them. That’s the way to treat the Englishman—stand up to him.” Charles’s temper was easily ignited, and during his last two years at Cambridge, he was involved in many physical fights. One night, after too much sherry and champagne, he assaulted a stranger in the street, who pressed charges. In May 1869, Parnell was summoned to court, fined twenty guineas, and suspended by the university for misconduct.

He was more than happy to spend a long summer at Avondale. In addition to building sawmills to capitalize on its timber assets, he intended to quarry the hills, situated in Ireland’s ancient gold-bearing region, for mineral deposits (finding gold became a lifelong dream). Still not ready to renounce English society, Parnell continued to go to parties in Dublin, to British embassy balls in Paris, and even attended an event at Dublin Castle—the bastion of British rule—where he was seen chatting about cricket to the lord lieutenant, the Crown’s representative in Ireland. He did, however, take a stand about not returning to England. He had been rusticated, not expelled, and so was entitled to take his degree, but Cambridge had come to symbolize what he most disliked about the English, and he had no further use for their elitist institutions. Besides, the twenty-four-year-old Parnell’s horizons were still confined to his estate: his prime concerns were to focus on his landowning interests and find a bride to bring back home.

*

The Anglo-American colony in Paris was renowned as a marriage market, and Parnell’s uncle, Charles Stewart, had a particular young heiress in mind for his nephew. A lucrative match would not only help with improvements to Avondale; it would ease the financial burden of the profligate Delia, who had been left nothing in her husband’s will and whose support was a responsibility now felt acutely by her son. But if Parnell’s designs on Abigail Woods had initially been mercenary, he was also seriously smitten at first sight. The daughter of a Rhode Island art collector, she had rather a schoolmistressy face but created an aura of beauty by dressing exquisitely and imaginatively styling her blond hair. Her father had brought her along on his Grand Tour of Europe and the Middle East with the idea of introducing her to art, culture, and—more crucially—a future husband. Already feeling that she was on the shelf at twenty-one—“I am sure that if I do not marry soon, I shall never marry at all!”—Abby did not hesitate to respond to the advances of the tall, refined Charles Parnell, delightedly accompanying him on evening walks alongside other courting couples in the Bois de Boulogne. For several weeks they were inseparable, and in February 1870, when the Woodses traveled to Venice, Parnell followed them and presented Abby with a gold ring. “I am glad I came for more reasons than one,” she wrote to her mother. “I think how anxious I know you will be but I am very prudent.”

Back in Paris after a visit to Egypt, she found herself being urged to marry a titled foreigner, mostly by her father, who was determined to separate her from this nondescript young Irishman. Mrs. Woods seems to have been more open-minded about the match, and Abby frequently confided in her. “The more I think of it, the more worried I become. Just think of the letter that I should have to send!” she wrote in June, adding a few days later: “You cannot tell how perplexed I am about him.” In August, when Charles’s gold ring broke in two, it seemed like a startling presage, but he hastened to reassure her that he was “not at all superstitious” and hoped that she was not either.

Always fearful of omens (“How could you expect a country to have luck that has green for its colour?” he later demanded), Parnell was in fact appalled, and the letter from Abby that arrived soon afterward, questioning their future together, seemed all too inevitable. His insecurity showed in his angry antipathy toward potential rivals; one, an American male friend, felt impelled to caution Abby about her choice of such an offensive fiancé. “He cannot bear him. I do not wonder for [Charles] treats people so coldly and contemptuously,” she told Mrs. Woods, asking, “What can I do to get out of this?” By September, she was relying on divine guidance—clearly not in Parnell’s favor—as she then wrote calling off the engagement and sending copies of the letter to her mother and grandfather (whom she was sure would be “very much pleased that it is all over”).

By now, Abby had returned to America, and Parnell, convinced that he could permanently win her over if he confronted her face-to-face, did not think twice about following her. Arriving at the Woods family mansion in Newport, he was so affectionately welcomed by Abby that he got the impression that “things were as they had been.” One night, however, when a rakishly handsome young man came into the room, he could tell by her reaction that there was some kind of bond between them. Sure enough, Samuel Abbott, a wealthy, Harvardeducated lawyer, much approved of by her parents, would be Abby’s husband within eighteen months. What shattered Parnell was not so much the idea of losing his fiancée to another man as the reason she gave for rejecting him. She had decided not to marry him, she said, because “he was only an Irish gentleman without any particular name in public.”

*

John Parnell, then living in Alabama, was surprised to receive a telegram from Charles announcing that he was coming to see him. A year earlier, John had bought a cotton plantation in West Point and, wanting to expand the business into a fruit farm, had just planted new orchards of peach trees, which he proudly showed his brother when he arrived. Almost the first thing Charles said was, “I want you to come home with me; you have been over here long enough.” But John, excited by his new enterprise, had no intention of leaving. He felt sure he knew the reason behind his brother’s sullen, dejected manner, and finally, after being pressed, Charles “poured forth the pitiful tale.” To distract him, John took him out shooting and on tours of the great Alabama cotton factories, gristmills, coalfields, and iron mines. Commerce—and in particular mining—fascinated Charles, and he wanted to know minute details of production methods in each place they visited. Instructed in American finance by his uncle, he had already taken a stake in Virginian coalfields and intended to invest a further £3,000 to become part owner of a mine in Warrior, Alabama. He might well have pursued a career as a mining magnate, had the brothers not been involved in a serious rail accident, which left Charles unhurt but injured John so badly that he should have been killed on the spot. Charles nursed John tenderly for over a month, and sleeping together in a small hotel bed, the brothers grew closer than ever before.

On New Year’s Day, 1872, they sailed back to Ireland, John to take over the running of his County Armagh estate, Charles determined to make a name for himself. Eventually, he would admit “it was a jilting” that had driven him into politics, and if the humiliation of Abby Woods’s dismissal still stung, the timing of it could not have been better.

*

Since the spring of 1870, there had been a major advance in Irish politics with the formation of a pressure group, the Home Government Association, fiercely campaigning for freedom from British control. Behind it was a brilliant barrister and MP named Isaac Butt, who was not only fighting for legislative independence but also taking the side of tenant farmers. At last it seemed as if the Irish might make themselves felt in England’s Parliament; a new form of nationalism was emerging—a distinct change of direction that combined a respect for the Fenian tradition of physical force with a commitment to English constitutional methods.

In front of the fire at Avondale one night, the Parnell brothers had discussed the consequences of Butt’s crusade. John, having gained insight into landlord-tenant relations by managing his own estate, stressed the importance of extending the tenants’ rights system throughout Ireland. In July, the perfect opportunity presented itself. Until this moment, smallholders, the mass of the population, had faced reprisal if they did not vote according to the will of their landlords, but the passing of a momentous new bill—the Ballot Act of 1872—allowed these employees to vote in secret for the first time. “Now,” Charles said, “something can be done.”

A direct result was the spectacular success in the 1874 general election of Butt’s movement, which had been reconstituted a year earlier as an official political organization, the Home Rule Party. Although Butt was still at the helm, he was proving to be conservative and overcautious, and both Parnells questioned whether he had the mettle to break though constitutional boundaries. “Charley and myself agreed that Butt was, if not too weak a man, at any rate too unenterprising to be leader of what then appeared to be a forlorn hope.” Although neither had any experience, they decided the time had come to try to enter the political field themselves: Charles’s position as high sheriff of Wicklow ruled out his candidacy for the county, and so John stood in his place. Unsurprisingly, he finished at the bottom of the polls, as Charles did when he took part in a Dublin County by-election later that year. In a result that surprised no one, the Parnell debut had been a disaster.

“He broke down utterly,” recalled the Irish MP and lawyer A. M. Sullivan.

He faltered, he paused, went on, got confused, and pale with intense but subdued nervous anxiety, caused everyone to feel deep sympathy for him. The audience saw it all, and cheered him kindly and heartily; but many on the platform shook their heads, sagely prophesying that if ever he got to Westminster . . . he would either be a “silent member” or be known as “single-speech Parnell.”

Parnell did succeed in getting into Parliament the following year, his arrival on the Westminster benches on April 22, 1875, coinciding with a groundbreaking Irish victory. At the time, Ireland’s politicians, hugely outnumbered and treated with mild contempt by their English counterparts, had no say over their own legislation—let alone any influence on constitutional decisions. Home Rulers—with one exception, a boorish, fearless man who had no respect for Britain’s revered institutions—had resigned themselves to obeying Westminster rules. In a speech lasting a full four hours, barely comprehensible in his thick Belfast accent, Joseph Biggar deliberately blocked the day’s business, making a mockery of parliamentary procedures. Watching with admiration and amusement, Parnell realized that Biggar, a former pork butcher with a round, jovial face, had inaugurated a formidable new Irish weapon: the tactic of obstruction, which, in more sophisticated hands, could be turned into a powerful system of political warfare.

Four days later, Parnell made his maiden speech. It was short and modest, spoken with evident nervousness, but he got across what he wanted to say—that Ireland was a nation in itself, not a geographical fragment of England. For the rest of the year, Parnell remained an undistinguished spectator. He was using the time to watch and learn the rules and customs of Parliament, studying its strengths and weaknesses in order to launch an effective attack. Slowly, by voicing advanced ideas, he attracted attention of the Fenians (his sympathy for the Manchester Martyrs was hailed as “a revelation”), and by 1877, the diffident neophyte had thrust himself to the fore. He had conquered his fear of public speaking and had begun adopting Biggar’s new strategy, his calm, tactical delivery raising bumbling verbiage into a fine art. “Even a critical colleague admitted he was a beautiful fighter. He knew exactly how much the House would stand.”

It had become obvious that Parnell should be leading the Irish party; Isaac Butt was an honorable politician, a gentle, kindly soul, who “could not bear to see even his enemies wince,” but having reached his sixties, he was battle-weary and unwilling to condone the obstruction tactic of the radicals. Parnell, by comparison, had all the dynamism and effrontery of youth, and although he endorsed Butt’s formula for a successful nationalist movement—the physical-force spirit working in tandem with constitutional methods—he knew that the government would never concede to Irish aspirations unless intense pressure was applied.

All that was missing now was Parnell’s alliance with an Irish trailblazer who had made it his life’s mission to bring down feudalism. “Everything was ready, or would shortly be, for the conjunction of a great agrarian leader with the great political chief.”

*

Michael Davitt, his face furrowed, hair thinned, and eyes sunken by seven horrific years in English prisons, was exactly the same age as Parnell, but the two men’s backgrounds could not have differed more. The son of tenant farmers in Famine-stricken County Mayo, Davitt had been four years old when his family was evicted for failure to pay its rent. Michael, his father, mother, sister, and a new baby just a few days old were all thrown out onto the roadside as their cottage was set on fire. When they were turned away from Galway’s poorhouse because Sabina Davitt refused to be separated from her children, the parish priest let them take shelter in his barn, and her husband went to England to find employment. He fell ill, and during the nine months he was hospitalized, Sabina labored in the fields by day and spun flax at night to pay for his return fare. Eighteen months later, the Davitts emigrated to Lancashire, in northwest England, and nine-year-old Michael went to work in a cotton mill, ordered to operate machinery that should never have been in the hands of a child. His right arm was crushed between cogwheels, and after a home amputation, to save his life, Michael was bedridden for several months. To pass the time, his mother used to tell him stories about “the wrongs committed by England on Ireland”—the brutal evictions she had witnessed, and an account of the 1798 rebellion, vengefully crushed by British troops. These tales “so fired his youthful imagination,” his sister recalled, “that he didn’t want to listen to anything else.”

A decade later, at the age of nineteen, Davitt joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and in February 1867 led a platoon of fifty Fenians who planned to raid Chester Castle for arms. Learning in time about a tip-off to the British, Davitt managed to extricate his men without being caught, but he continued to deal in IRB weapons, and a London transaction led to his arrest for treason felony in 1870. As a result of an informer’s false testimony, he was sentenced to fifteen years penal servitude—more than twice as long as his fellow gunrunner, who was an Englishman. In atrocious conditions of the notoriously desolate Dartmoor Prison, Davitt was singled out as an Irish political inmate and given such needlessly cruel and degrading treatment that it was impossible not to develop a loathing for the system that had allowed it.

In December 1877, he was released for good conduct on a ticket-of-leave for the remaining years of his imprisonment (his weight had dropped to 122 pounds, and his six-foot height had shrunk by an inch and a half). Davitt rejoined the Irish Republican Brotherhood and six months later, on a visit to New York, came under the influence of the exiled activist John Devoy, leader of the IRB’s American sister organization, the Clan na Gael. Convinced that constitutional and revolutionary nationalism could unite in the battle for self-government and a peasant proprietary—the “New Departure of 1878”—Devoy promised Irish American support for a more aggressive parliamentary party. Under Isaac Butt, the land question had taken second place to Home Rule, but Davitt believed that only when feudalism was abolished could Ireland achieve independence.

Back home, on a visit to his native County Mayo, he was so horrified by the plight of the smallholders that he organized what turned out to be a historic public meeting. Held in Irishtown in April 1879, it was this rebellious gathering that struck the match to an incendiary new movement soon to set Ireland ablaze.

Davitt knew that if he were to build on the momentum, it was essential to involve Parnell. The Dublin press had not reported the Irishtown demonstration, but an appearance at an upcoming tenants’ rights meeting by the most influential Irishman in the House of Commons would guarantee national coverage. Parnell’s prestige would not only give the nascent land campaign an enormous boost, but it would almost certainly guarantee the backing of Irish America.

Persuading Parnell to participate in the demonstration in Westport had not been easy. As a Protestant landlord himself, Parnell feared that he would be ridiculed for siding with the tenants, and it was only after several conversations that he gave his consent. To Davitt’s grateful surprise, Parnell kept to his word, even after a virulent attack on the proposed meeting by a prominent archbishop. “This was superb. Here was a leader at last who feared no man who stood against the people, no matter what his reputation or record might be. . . . I have always considered it the most courageously wise act of his whole political career.”

The Westport crowd that day was just as indifferent to clerical opposition. Raised on memories of the Great Hunger, this was a new, tough-minded, nationalistic generation of Irishmen who refused to be swayed. Their pent-up mass power excited Parnell, who agreed to take on the role of president of Davitt’s organization. And so it was that the Land League came about, its aim to achieve security of tenure, fair rents, and freedom for tenants to become property owners themselves. In just over a year, this mighty force of radical politics and angry populace would begin ruthlessly challenging the British domination of Ireland by decimating its landlord system.

*

Bertie Hubbard was a twenty-three-year-old cub reporter reluctantly covering an Irish political convention in Buffalo, New York, when he found himself transfixed by Parnell’s magnetism onstage: “The speech was so full of sympathy and rich in reason, so convincing, so pathetic, so un-Irishlike, so charged with heart . . . that everybody was captured by his quiet, convincing eloquence. The audience was melted into a whole.”