11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

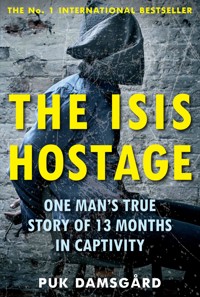

The Number One International Bestseller The dramatic story of freelance photographer Daniel Rye, who was held hostage for 13 months by ISIS, as told by an award-winning writer. In May 2013, freelance photographer Daniel Rye was captured in Syria and held prisoner by Islamic State for thirteen months, along with eighteen other hostages. The ISIS Hostage tells the dramatic and heart-breaking story of Daniel's ordeal and details the misery inflicted upon him by the British guards, which included Jihadi John. This tense and riveting account also follows Daniel's family and the nerve-wracking negotiations with his kidnappers. It traces their horrifying journey through impossible dilemmas and offers a rare glimpse into the secret world of the investigation launched to locate and free not only Daniel, but also the American journalist and fellow hostage James Foley. Written with Daniel's full cooperation and based on interviews with former fellow prisoners, jihadists and key figures who worked behind the scenes to secure his release, The ISIS Hostage reveals for the first time the torment suffered by the captives and tells a moving and terrifying story of friendship, torture and survival.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Foreword

The phone rang one afternoon at the end of May 2013. I had just returned home to Beirut after a two-week reporting trip to the Syrian city of Yabrud, which lies slightly north of Damascus. The trip had ended dramatically when the Syrian regime started sending fighter planes over the city. The bombs hit our neighbourhood and shattered the windows in the building where we lived. My photographer and I decided to leave Syria by crossing the border into Lebanon.

We were totally exhausted after working for days on end under the constant threat of danger. It wasn’t just the bombings that made us feel nervous, but also the Syrian rebels who came from the many different groups in the area. We just didn’t trust them. We knew that a French photographer was already being held captive a little further south. The mood in Yabrud had also changed considerably since I had been there a few months earlier and I was on my guard with everyone we met.

I was lying sprawled on the sofa, trying to recharge my batteries, when the call came. It was the accomplished war photographer Jan Grarup on the other end. He asked me to keep our conversation strictly confidential. I sat up as he told me that the Danish freelance photographer Daniel Rye, who had been his assistant, had been kidnapped in northern Syria.

‘Do you know anyone with contacts in the sharia courts?’ he asked.

‘No, I don’t think so – no one springs to mind,’ I replied.

According to the limited information available, a group of Islamic extremists were behind Daniel Rye’s abduction and he would apparently have to stand trial before a sharia court. However, Jan had only a few details. I felt powerless because there was nothing I could do to help. My first thoughts went to Daniel Rye’s parents. I had always worried that if anything like this should ever happen to me, my parents would be the ones to suffer the most, just sitting there waiting, with no idea where I was. It was too unbearable to contemplate.

The news of Daniel Rye’s capture was just one of several events that emphasized the fact that my profession was under serious attack. Several of my foreign colleagues had been kidnapped in Syria. It was a much-discussed subject, because the prospect terrified us. In principle, we were all potential hostage victims and this meant it was becoming increasingly difficult for us to tell the important stories of the war and to report on the tragedy unfolding in Syria.

Over the following year an increasing number of foreigners were captured. A feeling of panic was spreading through the journalist corps in the Middle East and in the closed circles where we discussed the kidnappings. People we knew were being held hostage for indefinite periods of time. When I returned to Syria in September and November 2013 and in June 2014 it was with a great deal of trepidation.

The Islamist terror organization known as ISIS set the agenda for where we could go. Even if ISIS disappeared from an area that had been under their control, their tentacles reached deep into Syrian society and souls. The armed men I met in northern Syria in June 2014 had a wild and unpredictable look in their eyes. As it turned out, my friendly driver was a former ISIS fighter. ‘But no more, Madame,’ he reassured me.

I couldn’t avoid the presence of ISIS in Baghdad, either. In spring 2014, ISIS attacked a stadium filled with several thousand people – men, women and children – who had come to a Shiite party election meeting that I was covering. When the first bomb exploded I completely lost my hearing and I hid behind a freezer in a makeshift street stall. When I saw bullets being fired wildly all around me I ran across the road, down which a suicide bomber drove his car shortly afterwards. It was a narrow escape and I felt the blast of the explosion against my back. More than forty people were killed that day. That spring the only positive news from the region was that several European hostages had been released after their ransoms had been paid, including Daniel Rye.

One evening in August 2014, while I was in a hotel room in Iraq, a video was uploaded on YouTube. It showed the murder of the American freelance journalist James Foley. He could be seen kneeling in an orange prison uniform in the Syrian Desert, at the hands of an ISIS executioner. An American colleague, whom I was supposed to meet for a beer later that evening, wrote to me that she was in total shock and we cancelled our plans. I couldn’t sleep that night. It was so utterly tragic for James Foley and his family, and it was also a brutal attack on journalism. With these new developments, it was no longer enough to prepare yourself and your loved ones for the unavoidable fact that bullets and bombs could strike when you’re covering a war.

I was now first and foremost a target; a potential and valuable political tool that could be used at will. The world was certainly no stranger to such tactics, but this was the first time, as a journalist, that the threat felt so intensely close, almost personal. Nevertheless, my greatest wish was to be able to travel to the ISIS stronghold in Raqqa and report on the Islamists and the life they had created for the civilians; I was keen to investigate them further and discover who they really were. Out of pure frustration at being so far away from the story, I seriously considered dressing in black from head to toe and travelling there with a trusted local.

Instead, I chose the next best thing. I decided to use my journalistic skills to write about what had happened to my colleagues and, through their stories, come a little closer to the core of ISIS. Daniel Rye had been a hostage along with James Foley, so I sent him a message via a mutual acquaintance, asking him if he would talk to me about his thirteen months of captivity at the hands of ISIS. He answered me on Facebook: ‘Hi Puk. My name is Daniel Rye. You’ve probably heard of me. I suffered a slight occupational hazard last year. Luckily for me, it had a happy ending.’ We met for the first time one Friday in early October 2014 at a basement restaurant in central Copenhagen. We agreed that Daniel’s story needed to be told.

The ISIS Hostage is about surviving one of the most notorious kidnappings in recent times – a hostage drama carried out by Islamic extremists, against whom much of the West is at war, including Denmark, since October 2014.

Twenty-four hostages – five women and nineteen men – from thirteen different nations ended up in the same prison in Raqqa in northern Syria. It was controlled by the terror group known as ISIS – it later changed its name to Islamic State (IS) – which has conquered and administrates large areas of Iraq and Syria. Daniel Rye was one of those hostages and, at the time of writing, he was the last prisoner to leave captivity alive. Six of his fellow prisoners were murdered while in captivity.

This book is a journalistic narrative based on countless interviews and conversations with Daniel Rye and his family, and it follows the struggle to get Daniel released from the clutches of the world’s most brutal terrorist organization. I also talked to a large number of other relevant sources: former fellow prisoners, jihadists and background contacts from around the world with extensive knowledge of the case and of the people who held Daniel Rye captive.

This story is also based on interviews with kidnapping expert and security consultant, Arthur. He led the search for both Daniel Rye and his American fellow prisoner James Foley, who ended his days in Syria. Arthur isn’t his real name; in fact, he lives a very discreet existence, which is crucial for his work in negotiating hostage releases all over the world. It isn’t in his nature to discuss his work, but he has nevertheless chosen to participate, because he believes that there is much to learn from this story. And, as he says, Daniel’s experience also shows that ‘where there’s life, there’s hope’.

This book describes the reality as experienced and remembered by Daniel Rye and the other contributors. It is told with respect for those who were murdered, those still in captivity and those who survived, as well as for their families.

Puk Damsgård

Cairo

September 2015

Happy Birthday, Jim

The plane had just taken off from Heathrow Airport and was high above the clouds when Daniel opened his wallet and took out a small piece of cardboard. He silently contemplated the white surface, studying the image of his own face sketched with thin pencil strokes. He wasn’t wearing his glasses in the drawing and he had a beard, but otherwise you could tell it was him.

He showed the picture to his travel companion, Arthur, who was sitting next to him, his long legs stretched out under the seat in front.

‘Actually, some of the stuff we did was quite enjoyable,’ said Daniel, gripping the mini-portrait tightly between his fingers. ‘We played our own homemade version of Risk and I did gymnastic exercises with the other hostages.’

The drawing was the only memento from his time held hostage by ISIS in Syria. It had been drawn by one of the other western prisoners, Pierre Torres, who had sewn it inside his sleeve and smuggled it out of captivity. Pierre was another of the lucky ones whose freedom had been successfully negotiated.

Once freed, Daniel feared the worst. The Islamic State started killing the remaining western hostages, which was the reason why, on 17 October 2014, he found himself flying over the Atlantic with Arthur on their way to New Hampshire. They were on their way to attend James Foley’s memorial.

Daniel put the drawing back in his wallet and ordered a glass of wine to accompany the predictable ‘chicken or beef’ in-flight menu. After the meal he fell asleep, his head resting on the still folded and plastic-packaged blanket he was using as a pillow. His hair was sticking up from the static electricity and his mouth hung open. He woke up five hours later, just as they were preparing to land in Boston. Outside the airport terminal he lit a cigarette in the clear autumn air and inhaled the smoke deep into his lungs. He didn’t usually smoke. In the meantime, Arthur went to pick up the keys for their rental car and they drove to their hotel on the outskirts of Boston.

The next morning they headed towards the Foley family’s home town, Rochester, New Hampshire. The eighteenth of October 2014 dawned with sparse clouds in the sky. On this day James would have been forty-one years old.

In August 2014 the American freelance journalist had lost his life in the Syrian Desert. He was the first western hostage to have his throat slit by the British ISIS fighter known in the media as ‘Jihadi John’.

Daniel had been held captive in Syria for thirteen months, spending eight of them in the company of James and other western hostages. Daniel had thought highly of James, who was always optimistic, even though he had been imprisoned since November 2012. They had had plenty of time to get to know each other and Daniel had listened to James’s anecdotes about his siblings and parents. Now he was on his way to meet them and to pay his final respects to a friendship that had started, and ended, in captivity.

The trees leaned forwards invitingly along Old Rochester Road, the narrow country road that wound its way through New England. Bright red maples stood out among the green pines, and shades of yellow, orange and brown clung to the branches like a final breath before winter fell. The scent of winter’s impending arrival mingled with the smoke from Daniel’s and Arthur’s cigarettes. Daniel scrolled through the music on his iPhone and played the melancholy song ‘Add Ends’ by the Danish band When Saints Go Machine – a song he had listened to countless times since James had been murdered.

Nestling between the trees were tall, well-kept houses and there were pumpkins carved into cheerful faces with star-shaped eyes or else frozen in menacing screams. These jack-o’-lanterns kept a vigilant watch from the lawns and driveways. Even the local grocery store was overflowing with them, almost blocking the entrance.

When they turned into the Foley family’s road, the orange changed to black. They passed a large house where a hooded skeleton guarded the door. The road curved among scattered houses and American flags that were stuck in the grass by the asphalt. The whole neighbourhood was in mourning for the tragedy that had befallen the family in the white house at the end of the road.

The large lawn at the front of the property was dense and damp, and light shone through the windows towards the driveway, where a couple of cars were parked. Daniel strode purposefully towards the front door, followed by Arthur. He knocked and entered when he heard voices. James’s parents, Diane and John Foley, greeted them as soon as they stepped across the ‘Welcome’ mat. Diane gave Daniel a long, maternal hug, her thick, dark hair brushing against his face as she held him close. She squeezed his arm and led him around the crowded kitchen to meet the family. Above the door between the kitchen and the living room were painted the words: ‘With God’s blessing spread love and laughter in this house.’ It smelled of coffee, perfume and toast.

‘Meet Daniel.’ Diane introduced him with a mixture of gratitude and pain in her voice.

After a year in captivity, Daniel had finally got the sense that he might be close to being released. James decided to send a message to his own family through Daniel, but he didn’t dare write a letter. If it were found, it would jeopardize Daniel’s release and might never reach his family. Instead, they sat next to each other in the cell and James dictated the words that Daniel repeated to himself over and over again until he could remember them in his sleep.

As soon as Daniel had been released and had arrived back in Denmark, he called Diane and repeated James’s message, word for word, over the phone. It was the only and final greeting the family received from their son in captivity. Diane wrote James’s words down to remember them.

For the memorial service she had printed out the words so that the guests and the rest of the world could read them too. The title was: ‘A Letter from Jim’. It included a note to his grandmother:

Grammy, please take your medicine, take walks and keep dancing. I plan to take you out to Margarita’s when I get home. Stay strong, because I’m going to need your help to reclaim my life.

‘Thank you, Daniel,’ said James’s grandmother in the kitchen as she gave his hand a squeeze. The slight lady with the pearl earrings wiped her eyes and looked as if she was about to collapse under the weight of her sorrow.

To his younger sister Katie, the woman with the long, smooth hair, James had said this:

Katie, I’m so very proud of you. You’re the strongest of us all! I think of you working so hard, helping people as a nurse. I am so glad we texted just before I was captured. I pray I can come to your wedding.

James’s brothers Mark, John and Michael were also standing in the kitchen. They all wore dark suits and shared the same features as James: brown eyes under wide, dark eyebrows and a broad smile. Daniel felt as if he had known them for a long time, as James had talked about them at length, because he missed them so much. Daniel also knew that the brothers had been longing for good news about their brother. His message had given them a new burst of hope for a while:

I have had good days and bad days. We are so grateful when anyone is freed, but of course yearn for our own freedom. We try to encourage each other and share strength. We are being fed better now and daily. We have tea, occasionally coffee. I have regained most of my weight lost last year […] I remember so many great family times that take me away from this prison […] I feel you especially when I pray. I pray for you to stay strong and to believe. I really feel I can touch you, even in this darkness, when I pray.

James had finally found peace from his torment and now the family was trying to find its way back from the darkness. Mark and his wife Kasey were expecting their first child.

‘His name will be James Foley,’ Kasey said proudly of her unborn son as she stood in the kitchen in slippers, caressing her belly.

The service was set to begin at 10 a.m. Everyone emptied their coffee cups and put on their shoes and coats to go to the church. Kasey kept her slippers on when the family went out to the car. Diane insisted on sitting next to Daniel in the back seat; she took his hand and held it tight, while John drove in silence towards the church.

Our Lady of the Holy Rosary Church in Rochester was packed with family and friends. In front of the altar was a picture of James Wright Foley. He was smiling his charming, lopsided grin, which by all accounts had brought him great success with women. Yellow and red flowers encircled his face, the eyes giving a sense of the affectionate troublemaker he was.

There was no coffin to put in the grave. James’s body had already been laid to rest somewhere in Syria. His family couldn’t bring themselves to look at the last image the world had seen of him: a body in an orange prison uniform lying on its stomach in the desert with the arms by its sides. On top of the body, between the shoulder blades, was the head.

Most of the media had refrained from showing the ISIS propaganda video of James’s murder. Daniel had watched it only to ensure that James was finally at peace. He had so many other images of James etched on to his brain and they flooded back to him as he sat in one of the front pews, staring straight ahead. His white shirt lit up like a moon against the dark jackets filling the church.

He thought back to one year earlier, 18 October 2013, when they had been together in captivity. Late in the evening James had casually remarked that it was his fortieth birthday. Daniel and the other prisoners had congratulated him and said they hoped his birthday would be better the following year.

Now Daniel was sitting in front of a photo of James, while Michael wept through his speech about a warm and loving big brother who had fought for a better world.

‘James died for what he believed in,’ he said.

Daniel could see James in Michael. He leaned forwards and put his elbows on his knees, his broad back shaking uncontrollably. It was the James he had known that Michael was describing to the guests; the James who always had time for others – even when they all knew that James might end up dying in captivity.

Daniel took off his glasses and sobbed towards the church floor, unable to repress a desperate wail, which came thundering out in convulsions from his stomach and along his spine. He let it all come flooding out for the first time since August, when Arthur had told him the news of James’s death. He wiped away the tears with both hands, exposing the red scars around his wrists. They were imprinted into his skin like tattooed bracelets. Daniel put on his glasses again and looked towards the altar with flushed cheeks.

‘Happy birthday, Jim,’ concluded the priest, and the congregation said a prayer for all the refugees in the world and the Syrians who were living in a bloody warzone for the third year. They finished the service by singing ‘I Am the Bread of Life’.

Outside the church, Daniel smoked another cigarette.

‘A demon has just left my body,’ he remarked to Arthur, before he screamed out loud to himself and to the autumn air: ‘James, you asshole! I miss you! Why the hell did you have to go and die?’

The family drove out to the graveyard. A flat grey headstone lay in the grass, surrounded by red maple leaves and yellow flowers. Diane put her arm around her mother’s shoulders as they stood in a semicircle and silently prayed. The clouds cleared and the sun’s rays hit the burial plot. Daniel looked at James’s headstone. It read: ‘A man for others’.

‘Look, here comes the sun. It turned out to be a bright day after all,’ commented Diane.

After the ceremony James’s family paid tribute to his life by holding a reception at the church. His former nanny remarked that he had died dressed in the bright orange colour of life, while the executioner wore the black robes of Satan. The priest, Reverend Paul, recalled one of the last evenings when he had eaten dinner with the family before James travelled to Syria.

‘I said to James that his brothers and his sister were not thrilled about his decision to travel to Syria, back into the lion’s den. “Father,” James answered. “I have to go back and tell the stories of the Syrian people. They’re living under a dictator who tramples all over them as if they were grass.”’ Reverend Paul added: ‘Here, we have food on our table, but we have no idea what the Syrian people are going through. I know that James’s mission came from the heart.’

Diane stood in the same spot for several hours, receiving condolences from the guests, who stood in a queue that wound around the entire room.

‘God bless you all,’ she whispered.

The next morning Daniel impulsively bought a sweater featuring New Hampshire’s revolutionary war motto ‘Live Free or Die’. Arthur and he also bought a couple of beers, some water and biscuits from an old lady’s convenience store and drove out to the enormous forest surrounding Lake Winnipesaukee, where James had spent time as a child.

Daniel pulled the burgundy ‘Live Free or Die’ sweater over his head and wandered with Arthur along the humid forest paths for hours, getting lost between the bare trunks and russet leaves. Daniel took a deep breath. It was just as quiet as it had been sometimes in captivity – or back in the field near his childhood home in Hedegård. He knew what it felt like to long for death rather than life. Among the tree trunks, in the clinging mud that weighed down their shoes, he shouted, ‘That’s my motto from now on, Arthur: Live Free or Die!’

The Elite Gymnast from Hedegård

Daniel clapped his hands at the audience from the stage of the Ocean theme park in Hong Kong. It was 15 July 2011 and he was dressed in a seahorse costume on a light-blue stage decorated with painted coral. Below him, he could see people with umbrellas shading themselves from the sun. Techno rhythms were booming so loudly from the speakers that parents had to shout to their children, who sat in folding chairs eating ice cream.

He looked up to where he could just make out a platform against the sky, which was at a height of twenty-five metres. He had to climb up there, jump off – and land in a three-metre deep pool. It was the climax of the show.

He pulled off the costume that fitted his body like a wetsuit and threw it away from him. The audience was enthusiastically cheering the blond, fit, tanned twenty-two-year-old Dane in his black bathing trunks, who was now beginning to climb up to the platform. Every muscle in his body was tense. This was the moment for which he had been rehearsing and waiting.

After a few weeks of performing, he had become tired of being a bouncing seahorse turning somersaults on a trampoline. He would rather be the cool, bare-chested diver, who jumped off the tower in a high dive. Daniel was a perfectionist and, even though this was just a holiday job in a Hong Kong arena, he had insisted on learning how to dive.

When he reached the platform, there was barely room for his feet. He stood on the small square, leaning against the metal behind him and clapped to get the audience going. Then he turned around and jumped out in a backward somersault.

The landing had to be precise − legs first, side by side. If he hit the surface askew or his legs were too spread out at the moment of landing, then, because of the entry speed, water would be forced up his rear end. Afterwards, it would be like he was pissing out of his backside, which he felt would be inelegant when he should be taking the applause from the audience.

The dive took him out of his comfort zone. But Daniel was an elite gymnast who had competed internationally, so it was the simplest thing in the world for him to perform moves like an Arabian Whip Double or a Stretched Whip Flick Double or a Stretched Whip Double Hip with a perfect landing.

Daniel had been competing for years in European and world championships in power tumbling, a branch of gymnastics in which gymnasts perform eight different elements on a fibre track. The dive in Hong Kong added a new height element to his physical abilities. It was frightening at first, but he soon got used to it.

During the six weeks he was working in the theme park, his attention began to be drawn towards the Middle East. In his breaks he read about the revolutions in Syria and Libya in the local English-language newspaper, the South China Morning Post. He cut out pictures of demonstrations from Syria and hung them up in the shipping container where the artists rested between shows.

The Syrians were demanding reform and these demands were being met with live ammunition and police violence. When President Bashar al-Assad refused to listen and instead deployed the military and the police against peaceful demonstrators, the protesters demanded the removal of his regime.

The seeds of the war in Syria had been sown.

· * ·

Daniel was born in Brøns, in south-west Jutland on 10 March 1989, the younger brother of Anita, who was seven years older. The family lived in a detached house where Daniel’s mother Susanne also ran a hair salon. His father was a fisherman. Susanne was meticulous with her customer’s hair, a trait which was also reflected in her insistence upon order and tidiness in the home. Daniel was just a year old when his father was diagnosed with brain cancer. One morning in early May 1992 he passed away on the sofa in the living room. His last wish was that Susanne would find a new man who could be a father to Daniel and Anita.

A few months later – and with that thought in mind – Susanne put her grief and obligations on hold for a night and went to a widows’ ball in a nearby town, where she met Kjeld, a tall, handsome man. They were married exactly one year after their first meeting on 11 September 1993 – a date which became a day of happiness in Susanne’s life. She and the children soon moved into Kjeld’s red-brick house in the village of Hedegård, close to Billund in south-central Jutland. Their new home was twenty brisk steps from the yellow house where Kjeld’s parents lived and where he himself had grown up. The couple had a daughter, whom they named Christina. Although Daniel had never known his biological father, he got a new one in Kjeld, who adopted him and Anita.

The family’s single-storey house was surrounded by fields and woodland and had a lawn covered with molehills. There were horses and cows on the neighbouring land and just up the road was the local village hall. Behind Susanne and Kjeld’s house was the big garage where Kjeld’s lorry was parked and where they celebrated special birthdays. The couple added a bay window on to the house and turned the bedroom into a hairdressing salon, where Susanne cut her customers’ hair during the day, while Kjeld made a living as a lorry driver.

Daniel passed his grandmother’s yellow-brick house on his way to Hedegård Free School, where Kjeld had also been a pupil many years earlier. It was on a narrow asphalt road with no street lights. Motorists drove fast out in the country, so Susanne sewed reflectors on to Daniel’s clothes. The neighbours smiled when he walked by and said that he looked like a Christmas tree. Susanne shushed them. If her son heard their jokes, he would rip off the reflectors.

As a youngster, Daniel loved to do somersaults and handstands. Susanne thought it was a healthy hobby and sent him to gymnastics in the neighbouring town of Give. From the floor of the hall, he soared through the air with extraordinary power and it was obvious to everyone that he had elite potential. When he got older, he dedicated himself to developing his gymnastic skills for two years at the Vesterlund sports boarding school, where he lived the disciplined life of an athlete and where, for the first time, he experienced a strange and unsettling sensation over a girl.

Her name was Signe and he loved her freckles, her reddish hair and her round, pale-blue eyes. She was the most talented girl in the school. She did the same jumps and somersaults as the boys, and Daniel noticed that she didn’t doll herself up with make-up and nail polish like the other girls. While in school they were sweethearts, but the relationship petered out afterwards when Daniel became busy with his apprenticeship as a carpenter and training with the national gymnastic team.

It became commonplace for him to be laying a roof on a house with a pain in his back and having to make regular appointments with a chiropractor, until he eventually decided to drop his apprenticeship.

‘I can always find time to become a carpenter. I can’t always be on the national team,’ was Daniel’s answer to his mother when she admonished him about not finishing what he had begun.

Instead, he made unsolicited applications to all the gymnastics schools in Denmark for a position as an instructor. A school in Vejstrup in the province of Funen snapped him up. He taught gymnastics for a year, while also building stairs and mowing lawns, between participating in competitions. He took up photography, too, inspired by the photos his coach took of him as he soared and rotated through the air. There was something in those frozen nanoseconds that fascinated him. They captured the tension in the muscles or concentration in the eyes. So he borrowed Kjeld’s SLR camera, which he took along in his bag when he went to compete in the World Championship in power tumbling in Canada in 2008. He photographed the gymnastics halls and hotel rooms; the bodies in their tight suits and the successes, sweat, somersaults and setbacks that shone out from the faces of the gymnasts. He photographed the gymnastics bubble in which he travelled around the world, and discovered that the camera was a tool he could use to explore people’s lives.

He soon took ownership of Kjeld’s camera, carrying it around with him to every competition. Later, he got in touch with his grandfather’s friend, whose son was a photojournalist. Hans Christian Jacobsen invited him to Aarhus, where he patiently looked at Daniel’s photographs of flowers and gymnastics. Afterwards, Hans Christian showed him his own photographs, which he had taken in some of the world’s most troubled regions. Daniel stared at a photo of a boy who was jumping into a lake somewhere in Kabul – shadows, light, a boy in a ray of sunshine. Hans Christian’s images sparked something in him and all Daniel could think about was getting out into the world and capturing it all with his camera. When he was twenty-one he bought his own camera, packed it in his rucksack and went off with his childhood friend Ebbe on his first trip outside the security of the gymnastics world. It was a journey that turned him upside down in a way that somersaults and back handsprings had never done.

Daniel sat several feet above the ground between the humps of a camel, looking at an expanse of sand in north-west India. The camel-driver was making the journey on foot in his long blue kurta, wearing a broad smile on his chubby face.

When they took a break during their five-day camel safari, Daniel couldn’t take his eyes off the camel-driver. The man would fetch his leather pouch from the animal and take out a few potatoes, a little fruit, some rice and spices, which he would then cook in a pot over a small fire.

‘He can make so much out of so little,’ thought Daniel and he took photos of this simple, quiet life and of the camel-driver, who was at one with the sand and the four-legged animal.

At night they slept out in the open. The stars had never shone clearer. The wild dogs howled and, during that summer of 2010, the sky seemed unusually high.

In India’s big cities the waste floated in the gutters and Daniel couldn’t always get to where he wanted, because of the cows and goats that wandered around freely and shat everywhere. The tuk-tuks sped by close to him and the air was heavy – even on the beach where the boys played football. Daniel struggled with the contrasts, as well as the overwhelming feeling that he couldn’t just escape into a gym. His travel guides were Lonely Planet and his friend Ebbe, who led him through a world of extreme wealth and extreme poverty.

Back in Denmark, Susanne could have won a world title in worrying as she followed Daniel and Ebbe’s accounts of their travels on Facebook. One mentioned that twenty Indians had been involved in a mob-fight that they had watched on a beach.

‘Mum, we’re fine! Nothing happened to us, except that we’re an experience richer,’ they wrote, while uploading regular videos from their journey. In one, Susanne and Kjeld watched Daniel do handstands on a beach, while gaping Indians stared at the unbelievably flexible white man. With a red shirt slung across his bare back, he declared casually on the video: ‘Three days ago, we arrived at Kovalam in Kerala, South India’s answer to Goa. We’ve been playing beach football and having a really, really good time.’

What they couldn’t see on the video were the changes inside Daniel. He had suddenly been torn away from his disciplined lifestyle. Now he was more often than not sleeping late, drinking beer at all times of the day and doing exactly as he pleased.

When he came home, he imagined he was back in Asia as he went through his photos and videos from the journey. He really wanted to learn the craft of photography properly, so he called Hans Christian, who suggested a photography course at the Grundtvig College in Hillerød, north of Copenhagen. Two days before the course began in January 2011, Daniel called the school.

‘How much time do you allocate to the actual photography?’ he asked. The answer was that they spent a lot of time on it.

‘Many people have followed their dreams here,’ was the message. Daniel no longer had any doubts.

The classroom door flew open. ‘What’s up, arseholes?’ shouted a loud, teasing voice.

The experienced war photographer and photojournalist Jan Grarup plodded across the floor, wearing desert boots, a white shirt and tight jeans, his fingers heavy with rings. While Jan was lecturing, Daniel stared at his role model, who had won countless international photo awards and followed his own wild path. Jan showed photos from his reporting trips and answered every question with the same answer: ‘It doesn’t matter.’

Nothing mattered – which camera you used, how to compose your pictures, how to trim them and edit them.

‘It doesn’t matter. It’s about taking your hearts and personality with you into whatever you’re doing and photographing,’ said Jan.

After the lecture, Daniel, in awe and with his heart pounding, went out on the terrace to find Jan. While they drank a cup of coffee, they discussed Daniel’s ideas about undertaking long-term photo projects – for example, following some young people in their development through a whole year of boarding school.

Daniel discovered at the college how little he knew about what was happening in the world. He would absorb as much information as possible from people who shared their love of their chosen field when they came and gave lectures. In the beginning he was unsure of himself and hid behind his camera; the praise he had become used to for his somersaults and rotations was absent from his photography teachers. He would often sit in his room, staring at his work, which he thought completely lacked talent, until one day his teacher, the art photographer Tina Enghoff, praised him for his cheerfulness, energy – and talent. In particular, she thought that Daniel inspired confidence, which would be crucial for him as a photographer to be able to get close to the people he wanted to photograph. While attending the college, Daniel became more self-assured, developed his photography skills and learned to talk to people who had interests other than gymnastics.

After finishing his photography degree Daniel started a higher education course in Aarhus, but he kept missing classes. He was spending most of his time taking photographs for The Gymnast magazine and was also in training for the 2012 World Team tryouts. He was practising the jumps and rhythmic sequences that the jury would be looking for when he and about ninety other young men gathered, hoping to be included among the chosen few. After a weekend with series, track jumps and exercises on the trampoline, the selection committee invited Daniel in for a talk with the eight judges. He was among the remaining twenty young men chosen to compete for fourteen places. The decision was long in coming, but it appeared in his inbox one day while he stared indifferently at his computer during a class.

‘Congratulations! You have been selected for the Danish Gymnastics and Athletics Association’s ninth World Team.’

Fourteen young men and fourteen young women were selected. Daniel packed his bag and took time off from his courses in order to tour with the World Team. But a chance event would change everything.

At one training session, Daniel stood contemplating the long black and white track in front of him before starting his run. As he set off, he sensed he would have difficulty making the height he needed. He tensed up in his hips and buttocks to squeeze himself through the full rotation before landing. When he landed in ‘The Grave’, as the landing spot was called, his hips were tense, where normally they should be more relaxed. The only place his body could counter the imbalance was in his legs.

Daniel jumped out of the landing and grabbed his knee. His friends shouted from the other end of the hall.

‘Oh, shit! We thought it was bad!’

‘Yes, something went,’ said Daniel, ‘but I don’t think it’s anything to worry about.’ He drove himself home to Aarhus, put ice on his knee and booked an appointment with a doctor.

‘You’ve damaged a collateral ligament and a cruciate ligament,’ the doctor said.

Daniel stared at him. ‘Does that mean that I can’t train and go on tour with the World Team?’

‘Yes, I’m afraid it does.’

Daniel burst into tears on the sofa. Then he rang Susanne and cried down the phone.

It was his final farewell to elite gymnastics.

Daniel was turned down for a course in photojournalism at the Danish School of Media and Journalism in Aarhus, but he was accepted by the University of South Wales in the United Kingdom, which had an undergraduate course in documentary photography. However, it would cost 250,000 kroner (about £26,000) for four years, which he couldn’t afford. Then he learned that Jan Grarup was looking for an assistant to help him with his photo archives – and to accompany him on a reporting trip to Somalia.

They wrote to each other over Messenger and Daniel sent some photos, including one of his high-dive in Hong Kong.

‘Do you have your passport ready?’ Jan asked.

Daniel sold his apple-green car to his parents and took the train to Copenhagen, where he alternately slept on friends’ sofas and at Jan Grarup’s place. Jan’s small office was filled with thousands of stock files, which Daniel was allowed to see. Going through the photographic records from Jan’s many years as a photographer in Africa, the Middle East and Asia was a journey of discovery into famine, disasters and conflicts, but the foreign faces came alive through his lens. Daniel gained insight into how to take photographs so that they captured a moment that stood out and told a story. He could feel Jan’s soul in the photos and how he moved with his camera.

Daniel began to look forward to the trip to Somalia.

Daniel sped through the streets of Mogadishu on the back seat of a four-wheel-drive vehicle, followed by a pickup with eight guards. They towered over the bed of the truck in their camouflage shirts, tall and thin and carrying machine guns. Daniel was travelling without Jan, who had gone off on a job and hadn’t allowed Daniel to join him. Through the car window, he saw skeletal houses that had collapsed due to bombs or were deserted and riddled by gunfire. Suddenly, in the middle of this spectral neighbourhood, he saw a football goal.

‘Stop! Can we stop here?’ he asked.

‘You’ve got fifteen minutes, max twenty,’ said the driver and Daniel jumped out with his camera over his shoulder. He knew that the Islamist militant al-Shabaab group would be able to sniff them out if they stayed too long in one place.

Children and elders in worn-out sandals were running around on the sand after a football, and when the kids saw Daniel, they ran over and passed him the ball, which he slammed into the goal. He squatted for a while with his camera in his lap to get them used to his presence. To the left of the makeshift football pitch, a bombed roof sloped down to the ground at a forty-five-degree angle and now served as a kind of viewing terrace from which people were watching the game. Daniel took photos, moving around between the players and loving the life-affirming fact that they were running about in their football jerseys amid such destruction. When his time was up, he returned to the car as agreed and they drove back to their guarded accommodation.

The photos from the football match in a bombed-out Mogadishu were part of a black-and-white series called ‘Born in War’, which he was documenting on this trip. It revealed what an incredible amount of hope he had seen in the war-torn city.

It didn’t occur to him how dangerous it was to travel around Somalia until he was back home, processing his time there. The far more experienced Jan Grarup had been responsible for their security, so Daniel hadn’t paid much attention. But it didn’t deter him. He knew more than ever that he wanted to be a photojournalist.

· * ·

Daniel had been travelling in the aftermath of a civil war in Somalia, but in the autumn of 2012 it was the Syrians who were at war with themselves. A popular revolution demanding reform had turned into a full-scale battle between armed rebels and a brutal regime. Daniel read articles and searched for images on the Internet that could give him greater insight into the conflict. He looked at photographs of bombed-out houses, lifeless babies covered in dust who had been dug out of ruins, camouflaged snipers lying in wait with Kalashnikovs, ambulances unloading the wounded at hospitals.

He couldn’t find anything to compare with his football pictures from Somalia in the coverage of the Syrian conflict. The faces in the images merged into one another and he wondered what he should photograph to make Danes more aware of the war. How could he focus people’s attention on a bloody conflict far away, where President Assad was sending bombers over Aleppo, the country’s second largest city and industrial centre, in an attempt to put down the rebellion?

The sound of the bombers had become an everyday occurrence for Syrians, just like the cluster bombs and Scud missiles that rained down on civilian areas. The rebels were fighting in different factions under the Free Syrian Army (FSA), but the opposition couldn’t agree on a common goal and infighting had arisen between several of the rebel groups, who were also committing more war crimes in response to the hardening effect of their environment.

New groups were springing up each week – some of them with a more Islamist identity than had been seen in the war thus far. One of the largest and most powerful Islamist groups was Jabhat al-Nusra, which later turned out to be the Syrian branch of the terrorist organization, al-Qaeda. Jabhat al-Nusra was growing rapidly, with the goal of ousting the Assad regime and creating a more Islamist government. The group operated under the leadership of a Syrian war veteran, who, like hundreds of other jihadists, had crossed the border between Syria and Iraq with Assad’s approval to fight the Americans in Iraq after the invasion in 2003. The self-proclaimed Emir of Jabhat al-Nusra, who went by the nom de guerre of Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, was a man the world knew very little about and who had for a long time kept the group from being directly associated with al-Qaeda. Instead, it had been created as a Syrian organization that looked after the interests of Syrians.

Jolani had been held at the US base Camp Bucca in the Basra province of southern Iraq. He had also been imprisoned for a while by the Assad regime and rumour had it that he had been crammed in with hundreds of other Islamists in Syria’s notorious torture prison in Sednaya, near Damascus.

At the beginning of the revolution in May and June 2011, President Assad granted amnesty to numerous political prisoners from Sednaya – most of them with a pronounced Islamist profile. The president was aware that the prisoners were likely to join the rebellion once they were released and would Islamicize it. This would benefit the Assad regime by supporting its narrative that the revolutionaries were ‘terrorists’, dangerous to Syria and the region as a whole. The plan worked as intended and the threat from the Islamists became a self-fulfilling prophecy, not least because the Assad regime was primarily attacking the moderate factions. As had been seen so often before in the Middle East, corrupt totalitarian regimes and militants kept each other busy and used each other in an almost symbiotic relationship.

Some of the prisoners released from Sednaya joined Jabhat al-Nusra, and in the autumn of 2012 fighters from the weaker and more secular factions of the Free Syrian Army also began to switch to the more successful Jabhat al-Nusra, where they had access to better weapons and stood in a stronger position alongside more fearless, experienced soldiers. In December 2012 Jabhat al-Nusra was added to the US list of terrorist organizations, because of the movement’s links to al-Qaeda in Iraq, but that didn’t stop its momentum in the Syrian Civil War.

In March 2013 Jabhat al-Nusra and another Islamist movement, Ahrar al-Sham, announced an offensive called ‘The Raid of the Almighty’ against the city of Raqqa in north-east Syria. Raqqa was the first provincial capital to fall quickly to the rebels. The black Jabhat al-Nusra flags flew over the city and the rebels captured the government’s administrative headquarters, where they recorded a video of the captive governor which was broadcast on the opposition-friendly channel Orient Television. The Assad regime had lost its grip on Raqqa to groups with an Islamist profile.

Meanwhile, the civilians were caught in the middle. In Aleppo wide pieces of fabric were hung across streets and alleyways to block the snipers’ view into people’s apartments. Schools were either closed or destroyed and it had become difficult to find food. The lines of fire, the battle fronts, and the regime and rebel checkpoints constantly moved around residential neighbourhoods. Those who could packed a couple of blankets, some clothes and fled.

While the civilians were fleeing, several thousand foreigners from Arab and western countries came to join the fight in Syria.

One of them was the Belgian Jejoen Bontinck.

· * ·

Jejoen’s friends had already gone to Syria. They had been recruited through the network Sharia4Belgium, which regularly contacted Jejoen to persuade him to take part in the war. He had just turned eighteen and had no girlfriend, no job and wasn’t in school, so there was nothing to prevent him from seeking adventure. In February 2013 he packed his father’s sleeping bag and told him he was going to Amsterdam with some friends.

It took less than a week for the young Belgian-Nigerian man to arrange the trip from Belgium through Turkey to the Syrian governorate of Idlib. Friends from Sharia4Belgium who were already in Syria described the route for him. Like many other fighters in Syria, he travelled through the official border crossing at Bab al-Hawa and, on 22 February, after a short drive, he arrived at a large villa in the Kafr Hamra neighbourhood, a well-to-do suburb of Aleppo, just north of the city. He didn’t know which faction he was actually joining, but he had been reunited with his friends.

The water in the villa’s pool was dark green and shallow, while the lawn around it looked like a park where the flowers and shrubs hadn’t been attended to for a long time. Jejoen was far from being the only foreigner. The grounds were huge and teeming with Dutch, Belgian and French men. When he first arrived, he worked out that there were at least sixty of them and eventually some had to be moved to another villa, because there wasn’t enough room.

Jejoen was welcomed by a man who bore the nom de guerre Abu Athir. Several of Jejoen’s friends just called him ‘sheikh’, as he was the leader of the Mujahideen Shura Council faction. Abu Athir had been hit in the leg by shrapnel and hobbled about the villa on crutches, surrounded by guards. He never carried a weapon, but left it to the European fighters to guard him as he drove around the area, either in a Jeep or a Mercedes.

There was a hierarchy in the organization and the new recruits had to work their way up and win Abu Athir’s trust before being sent to fight on the front lines. Abu Athir and his men had developed an elaborate vetting process, so recruits went to the front only when they had been tested and were clearly not working for foreign intelligence services. Newcomers were initially given the task of guarding either the villa in Kafr Hamra or Abu Athir himself when he was in meetings or sleeping.

The fighters whom Jejoen met were roughly the same age as him. Some had left their jobs or studies to fight in Syria; others were like him, with nothing to lose. When they arrived, they responded only to the warrior names they had chosen for themselves. Some of the foreign fighters already spoke Arabic and many of them established themselves in Syria by marrying locally or bringing their wives into the country. They wanted to live their life in the coming Islamic state.