Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

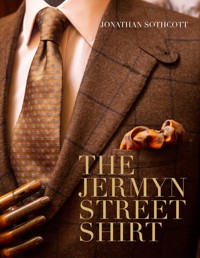

Jermyn Street in St James's, London, has been the Mecca of fine British shirtmaking for more than a century. Patrons have included Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, Roger Moore, the Beatles, Warren Beatty, Pierce Brosnan, the Prince of Wales, Sir Michael Caine and Ronald Reagan. Between them, these shirtmaking artisans have styled that most debonair of onscreen heroes, James Bond. Indeed, the Jermyn Street shirt is the ultimate in entry-level luxury menswear. For many years seen as a stuffy and elitist institution, the advent of Instagram has seen the doors to the world's finest shirtmakers blown open as tailoring enthusiasts come together to share their passion. The Jermyn Street Shirt includes a wealth of sartorial showbusiness anecdotes as well as style tips from some of the big screen's most dapper stars. With unique access to many of the makers, including Turnbull & Asser, Hilditch & Key and Budd, Jonathan Sothcott presents an expertly curated pictorial treasure trove of previously unseen ephemera, including celebrity shirt patterns and samples.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 165

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THEJERMYNSTREETSHIRT

For Jeanine – the love of my life and my perfect fit

All original photography by Rikesh Chauhan. All other photography kindly provided by the shirtmakers of Jermyn Street.

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Jonathan Sothcott, 2021

The right of Jonathan Sothcott to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 7775

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by IMAK

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

JS on Jermyn Street – My Life in Shirts

The English Shirt

Fabrics

Collars

Cuffs

Shirt Fronts, Sleeves and Pockets

The Devil is in the Detail – Dos and Don’ts!

Caring for Your Shirts

The History of Jermyn Street

The Bespoke Process

The Shirtmakers of Jermyn Street

And While You’re on Jermyn Street

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have fostered my interest in fine menswear over the years, but I’d particularly like to acknowledge three who are sadly no longer with us: the late Sir Roger Moore, not just for endless sartorial inspiration but also for introducing me to my shirtmaker, the late Frank Foster; Frank himself; and my first tailor, the late, much-missed Doug Hayward, who was as much a one-off as any of the beautiful suits he cut with such flair.

My wife Jeanine who not only appreciates my shirts (and remarked on one the first time we met) but washes and irons them too. That is true love.

My dear friend Tom Parker Bowles for such kind words in the foreword and for his unflagging support and enthusiasm both for this book and for all that I do.

Tom Chamberlain, not only for writing such an elegant introduction, but also – in his role as editor of The Rake magazine – finally giving us sartorialists the men’s magazine we’ve always wanted.

For graciously giving their time to talk to me for the book: Emma Willis, Robert Emmett, Stephen Lachter, Steve Quinn at Turnbull & Asser, Charles Seaton and Carla Bicknell at New & Lingwood, Richard Harvie at Harvie & Hudson, John Butcher and Darren Tiernan at Budd, Nick Wheeler at Charles Tyrwhitt and Steve Miller at Hilditch & Key.

Rikesh Chauhan whose stunning photography captured the elegance of Jermyn Street so effortlessly. Mark Beynon at The History Press for indulging my whim to write a book about shirts and forgiving my flagrant lack of respect for deadlines.

Billy Murray, Geoffrey and Loulou Moore, Adam Stephen Kelly, Jamie and Claire Barber, Ewan Venters, Paul Sandgrove, Terry Haste, Les Haynes, Audie Charles, Peter Brooker, Matt Spaiser, Simon Thompson, David Marlborough and Poppy Charles.

At home, Dylan, Hannah, Grace and Gabriel. And my Mum and Dad for that first Turnbull & Asser shirt.

FOREWORD

TOM PARKER BOWLES

Film producers are not, on the whole, known for their distinctive sartorial style. Sure, Robert Evans worked a particularly louche West Coast look, all cashmere polo necks and black silk shirts. David Heyman wears a well-cut suit. And Alexander Korda was never knowingly underdressed. But the vast majority could be charitably described as, at best, scruffy. At worst, a bloody mess.

Not Jonathan Sothcott. Hell, no. The first time I met him, about ten years back, was at Langan’s. I turned up looking, as ever, as if I’d had a fight with a tumble dryer. Jonathan, on the other hand, was clad in an immaculately cut double-breasted blazer (pristine white handkerchief peeping exactly an inch from his breast pocket), grey slacks with a crease so sharp it could slice garlic, bespoke Frank Foster shirt (with the plain white collar, of course), and a pair of gleaming Gucci loafers. This was Jonathan in casual mode.

Since then, and over the course of countless long and invariably merry lunches and dinners, I’ve never seen him dressed in the same thing twice. Sometimes, the jacket may be fine tweed; at others, a lightweight wool. And as the days get longer, so the pastels emerge, in linen jackets and poplin cotton shirts and the sort of white slacks that I thought only Cary Grant could pull off. He puts as much care, love and attention into his clothing as he does into producing his films.

I’m not sure if he has ever worn a T-shirt or, God forbid, a pair of tracksuit bottoms. And on the few times I’ve seen him ‘dressed down’ (two words I don’t think he uses much), there’s usually some incredibly grand overcoat, or Roger Moore-style blouson jacket. And talking of the late, great Sir Rog, you can see the influence the actor had on Jonathan’s dress. His shirts, in particular. They were great friends, and I force him to recount the same old anecdotes, time after time. They never lose their charm.

Anyway, I can’t think of a more fitting, knowledgeable or passionate guide to The Jermyn Street Shirt. God only knows how many he has, although I’m pretty certain they’re hung with colour-coded precision. There’s nothing he doesn’t know about spread versus cut-away collar, or sea island versus lightweight voile. And don’t even get him started on those cuffs. He can talk for days. But in a world where the bespoke shirt is an increasingly rare luxury, Jonathan keeps the flag flying. For British style, craftsmanship and the pure, elegant joy of a proper handmade shirt.

INTRODUCTION

TOM CHAMBERLAIN

The first bespoke shirt I ever had made was a two-fold white cotton shirt from Emma Willis. Like many people I know who have explored this particular bespoke avenue, I felt a sense of overindulgence; that bespeaking a suit can be easily justified, but what lies underneath the suit surely doesn’t need it, right? The result converted this particular agnostic into a passionate evangelist on the beneficial effects of bespoke shirts. Since then the journey has taken me through several of the different shirtmakers in Mayfair and St James’s who have met the challenge of staying relevant and living up to the expectations created by their own heritage by producing clothing that is not only adaptable to modern needs, but still conjures that intoxicating feeling that someone who has dedicated their life to a particular art has focused their energy on you. It is a precision craft that is more like shoemaking than tailoring, as the end product will have no overlay and the margin for error is effectively zero.

When Jonathan, a friend through being a reader of The Rake, asked me to write the introduction to a book on Jermyn Street shirtmakers, there was some confusion. Not that a film producer was writing this book – no, he’s an articulate, passionate, knowledgeable author for the subject. The puzzlement was simply that this was a book that has been written before, surely? Sartorial matters are one of the nation’s great exports, and Jermyn Street is the beating heart for shirts. But I was wrong. Aside from the in-house books on specific brands, there is a dearth of published books on this street as a whole, with anything already out there so softly grazing the surface that it is instantly forgettable.

It is therefore with great pleasure and privilege that I get to introduce a book that understands how rich and fertile a soil this subject matter is for telling stories. Shirts are, from a common cultural point of view, undoubtedly perceived as occupying a second-fiddle position against the suit. What this book demonstrates, by getting to grips with the field and its players, is that there is very little to support this prejudice. It elevates not only the esteem of the shirt as a work of art, but also the makers as artisans comparable with tailors, working under the roofs of brands with just as much heritage as any house on Savile Row.

Over the course of the book, as each brand’s nuance, heritage and technique is illuminated to you, Sothcott’s passion will no doubt leave you in a state of blissful indecision. For when the quality across the board is so high, the most pressing question should be: whom do I go to first?

JS ON JERMYN STREET – MY LIFE IN SHIRTS

The prospect of a book – written by me – about fine and bespoke shirts, and more specifically those made on or around Jermyn Street, has largely met with two views from friends. Some have said, ‘Fantastic, that’s a wonderful idea.’ Others have said, ‘German what? What do you mean “shirts”? Be spoken to like what?’ All have – largely kindly – agreed it is a perfect book for me to write because, despite my somewhat self-propagated public persona as the king of gangster B-movies, the truth is that that’s work and something I very much leave at the office.

Like many men of my age (I was born in 1980) my interest in menswear began with James Bond. The old saying that men want to be Bond and women want to be with him is an undoubted truth, but while Bond’s suits have been the subject of countless column inches and internet pages, his influence on men’s shirts cannot be overlooked. Growing up on the classic Sean Connery and (particularly) Roger Moore films, in my teens I aspired to the classic, understated style on display in these movies, which was jarringly at odds with the loud, often acidic colours, baggy fits and stylistic excesses of 1990s fashion. I never followed fashion or owned a pair of trainers and was doubtless something of an eccentric in my youth. Terms such as ‘old head on young shoulders’ and ‘old before his time’ would be bandied about in less than flattering contexts, but nonetheless brands such as DAKS and Aquascutum were far more appealing to me than Nike or Hugo Boss. In my school sixth form I paraded about in a DAKS double-breasted Prince of Wales check suit with a striped tie and cufflinks while my peers resentfully wore their fathers’ discarded work wear, counting down the days until they could get changed into trainers and sweatshirts. At the time, the closest I got to Jermyn Street or Savile Row was the sprawling department stores such as Army & Navy and Alders that dominated large towns. Alders in Croydon, where I regularly found myself, stocked brands such as DAKS for suits and blazers but, like most stores, no comparable shirt brands – there were a lot of soft-collared Van Heusen shirts which, while not without merit, were decidedly cheap and cheerful and certainly weren’t comparable in quality to the garments retailers expected them to sit under. It always seemed strange to me that there was still a perception that shirts were largely a complex undergarment and that only the jacket over them mattered.

In 1997 my mother bought me, as a huge indulgence, a blue Bengal striped shirt with a white collar and white double cuffs from the Turnbull & Asser concession in Harrods. It was to lead me on a journey around the shirtmakers of Jermyn Street and beyond over the next two decades. Fine shirts were my first menswear love: they were more affordable than jackets or suits and the plethora of styles and patterns made them an instant focal point for my early wardrobe. There is an old Jermyn Street saying that the suit is the frame and the shirt is the artwork and it is one that has always stuck with me. That first Turnbull & Asser shirt opened my eyes to the fact that there was a whole world beyond the Van Heusen and Savoy Taylors Guild shirts I had aspired to in my teens. The removable stays gave the collar a regal, luxurious feel. The stripes seemed that little bit more defined. The cuffs were full and rich, with plenty of soft, silky material. They felt worthy of cufflinks. It felt like a rite of passage. I had graduated. Fine shirting was not only one of the great institutions – it had its very own Mecca: Jermyn Street. And it was calling to me.

I still remember that crisp, chilly morning heading to Jermyn Street from Green Park tube for the first time, a few months later. Walking past The Ritz Hotel, I was struck by an explosion of colourful menswear in one of its windows – the Angelo Roma boutique, sadly no longer with us. Eventually I made it across St James’s and there it was – one long, beautiful street of shirts, ties and accessories. Another explosion of continental colour was provided by what was then the first menswear store on the street – Italian luxury specialist Vincci, which specialised in plush cashmeres with brass buttons in much the same style as Brioni and indeed Angelo.

Even then, at the risk of cliché it was like stepping back in time (and two decades on, even more so) – there was an air of Grace Brothers about the service in some of the shops, for sure, but not in a bad way. And there were esoteric items in some of the windows which took me by surprise even then – I can still see in my mind a lightweight (and thus entirely fashionable and unfit for purpose) checked Inverness cape in the long-closed Baron of Piccadilly, a garment I have never seen someone wear anywhere except on the silver screen. Baron was a curious place, seemingly trapped in 1979 for three decades, selling a strange mix of excellent tweeds by the likes of Magee offset by a deluge of polyester-rich ‘leisure wear’ of the sort sported by Brits on cruise ships in situation comedies. The staff were of the personable, no-nonsense school characterised by country department stores for decades and largely of the opinion that everything one tried on was ‘just the ticket’ – and in some cases they were right. It was no surprise – yet still rather sad – when it closed its doors in 2009. And, of course, I still regret not buying that Inverness cape which I’d never, ever have worn.

One of the things which most stood out on Jermyn Street was its adherence to classicalism, which simply could not be found on the high street. The ’90s were the era of the dreaded black business suit paired with matching shirts and ties, and Jermyn Street offered the counterpoint of colour and pattern to this monochromatic monstrosity. Bold stripes in reds and blues, yellows and creams to match browns and tans. Everything was thought out. How you put an outfit together could be rewarding, not just a chore. Then, as now, I always started planning my outfit with the shirt (I suspect for most men it is the suit, or at the very least the jacket) – it is the centre point of a gentleman’s ensemble, for while he may take off jacket, tie and even shoes, nobody but his most intimate acquaintances will ever see him without his shirt.

That first day, I came home with a red and white striped shirt with a white collar from Herbie Frogg – another brand lost in the mists of time. Frogg was perhaps the raciest store on the street, located at the theatre end opposite Rowleys. It housed a curious mix of Italian suits and British shirts in bolder, more modern colours than most of its neighbours and certainly didn’t conform to the fashion-backward style that defined the street. But its shirt was, for me, another triumph and, paired with a solid red tie, made me feel like I was ready to take on Wall Street. It is fair to say that, from that day on, Jermyn Street became part of my life and I have been going back ever since.

It is hard not to be intoxicated by Jermyn Street – aside from the bountiful wardrobe shopping, it offers some of the finest cigars (Davidoff), cheese (Paxton & Whitfield, whose wares waft delightfully down the street), books (Waterstones and Hatchards) and restaurants (45 Jermyn Street, Wiltons, Rowleys), and even has a theatre, the delightfully compact Jermyn Street Theatre. In the middle of the street towers Fortnum & Mason, rightfully the world’s most revered department store. There really is nowhere like Jermyn Street.

In my early twenties I wrote the film column for an arts and media magazine called The Grapevine, published and edited by British screenwriter Michael Armstrong (House of the Long Shadows, Eskimo Nell) under his Armstrong Arts banner. As part of his burgeoning empire, Michael ran drama classes and staged showcases for his students at the Jermyn Street Theatre. For me, this was the highlight of the job, not because I was particularly enamoured with the acting, but because it was an excuse to spend a day on Jermyn Street. I would often sit next to another legendary British film screenwriter – Barbarella scribe Tudor Gates (his real name), who was about as dapper as the industry allowed – and even he was baffled at my interest in collars and cuffs.

It wasn’t all great, of course. Like everyone, I was seduced by some of the cheaper options. An outfit called Crichton based in Sackville Street on the other side of Piccadilly made me four shirts for a ludicrously low price which was reflected in the fit, fabric and style – definitely a case of breaking a few eggs to learn how to make an omelette. And to be honest, this is why you have to really think about what you want from a shirt, particularly if you are having one made. Another shop, long since gone, which was in the Piccadilly Arcade, made me a shirt that the elderly proprietor hard-sold me as bespoke but which turned up with a collar so small that my 8-year-old son would have looked silly in it. Unfortunately, as with all luxury goods, shirt making does attract the odd cowboy, though thankfully less so now that the world is more joined up by the internet.

In the past two decades I like to think I have patronised most of the key players on Jermyn Street, not merely buying shirts but also ties, trousers, jackets, handkerchiefs, coats, scarves and sweaters. Having ended up as a film producer, I dress smartly because I want to and like to, not because of any expectation from my profession – indeed, my dear friend Billy Murray once said to me, ‘Jonathan, it’s no good you keep coming to set in a suit and tie because nobody believes we are making low budget movies.’ It is very rare to meet anyone in my profession who has any interest in fine British menswear. A rare exception is my friend Gary Kemp. I treasure a lunch at that venerable Jermyn Street institution Wilton’s with him, followed by a stroll along Jermyn Street and Savile Row.