Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

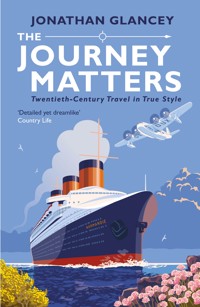

What was it really like to take the LNER's Art Deco Coronation streamliner from King's Cross to Edinburgh, to cross the Atlantic by the SS Normandie, to fly with Imperial Airways from Southampton to Singapore, to steam from Manhattan to Chicago on board the New York Central's 20th Century Limited or to dine and sleep aboard the Graf Zeppelin? In the course of The Journey Matters, Jonathan Glancey travels from the early 1930s to the turn of the century on some of what he considers to be the most truly glamorous and romantic trips he has ever dreamed of or made in real life. Each of the twenty journeys allows him to explore the history of routes taken, and the events - social and political - enveloping them. Each is the story of the machines that made these journeys possible, of those who shaped them and those, too, who travelled on them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 543

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE

JOURNEY MATTERS

By the same author

Wings Over Water

Concorde

Harrier

Giants of Steam

Spitfire: The Biography

Nagaland: A Journey to India’s Forgotten Frontier

Tornado: 21st Century Steam

Architecture: A Visual History

London: Bread and Circuses

THE

JOURNEY MATTERS

Twentieth-Century Travel in True Style

JONATHAN GLANCEY

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jonathan Glancey, 2019

The moral right of Jonathan Glancey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-416-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-417-7

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-418-4

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards

Lines from ‘Night Mail’ in W. H. Auden’s Collected Poems, copyright © 1938 by W.H. Auden, renewed 1966, reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In memory, Don Pedro

Contents

Map

Introduction

1. Londonderry to Burtonport: Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway

2. The Brill Branch: London Transport

3. Frankfurt to Rio de Janeiro: Graf Zeppelin

4. New York to Southampton: SS Normandie

5. London to Glasgow: Coronation Scot

6. Dundee to King’s Cross via Edinburgh: Coronation

7. Southampton to Singapore: Imperial Airways

8. New York to Chicago: 20th Century Limited

9. Chicago to Minneapolis: Afternoon Hiawatha

10. Bristol to Paris: Bristol 405

11. Liverpool Street to Hammersmith: Route 11

12. Massawa to Asmara: Ferrovie Eritrée

13. Birmingham to London: Midland Red

14. Milan to Rome: Il Settebello

15. The Black Mountains and Elan Valley: Jaguar Mk 2

16. London to Fort William: West Highlander

17. Tongliao to Hadashan: QJ

18. Baghdad to Basra: Toyota Land Cruiser and Chevrolet Suburban

19. Wolsztyn to Poznań: 0416 hours

20. London to Helsinki via Travemünde: Jeep Cherokee and MV Finnpartner

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Illustration Credits

Index

Introduction

Chicago O’Hare Airport, 1740 hrs, 9th April 2017

Boarded and fully booked, United Express Flight 3411 to Louisville, Kentucky, operated by Republic Airways on behalf of the United Airlines subsidiary, was at its gate ready for departure. A sky bully came on board the Embraer 170 jet and said four passengers had to give up their seats. The airline wanted these for its own staff. There were no volunteers, even when a first offer of $400 compensation was raised to $800.

In the end, four passengers were selected by computer to be bumped. Three complied, but the fourth, Dr David Dao – a 69-year-old doctor who was flying back to Kentucky to see patients the following morning – was unwilling to give up his seat. So, instead, he was wrestled from it by three baseball-capped operatives. Dragged unconscious along the aisle, his nose and two of his teeth broken, blood trickling down his face, the doctor was taken off the aircraft. Fellow passengers filmed this malevolent scene on their mobile phones. Videos would go viral on YouTube, although not before Dr Dao had managed to re-board the aircraft. This time, the wounded, concussed and evidently distraught medic was dispatched on a stretcher.

Airline staff took their hard-won seats. Flight 3411 departed O’Hare two hours late. A later press statement claimed that the airline had simply been ‘re-accommodating’ passengers, and a leaked internal email said that employees had ‘followed established procedures for dealing with situations like this’. Who could think of criticizing United’s Oscar Munoz, the very model of a modern airline CEO, with years of experience working for AT&T, Coca-Cola and Pepsi? The previous month, PRWeek magazine had named him its ‘Communicator of the Year’. He held an MBA degree from Pepperdine University, a devoutly Christian college near Malibu, California.

The following month, United flew more passengers than it had a year earlier. It posted significant gains in passenger miles flown, and recorded the fewest cancellations in its history. The airline’s share price hit an all-time high. Warren Buffett, the veteran business magnate and a major investor in airline stocks, told Fortune that although United had made a ‘terrible mistake’ over the Dao affair, the public wanted cheap seats. This meant ‘high-load factors’ and, for passengers, a ‘fair amount of discomfort’.

A gun barrel of online US commentators said, in no uncertain terms, that Dr Dao deserved every injury and humiliation that came his way. How dare he delay other passengers and obstruct an all-American corporation going about its lawful business? As for the assault on the doctor, one of his three assailants, the aviation security officer James Long, felt he had been unfairly dismissed as a result of attempts by United Airlines to placate those Americans, including President Donald Trump, who said its methods had been wrong.

Long took legal action against United Airlines and Chicago’s Department of Aviation, claiming that he had not been trained properly in the handling of out-of-line passengers. How was he to know that violence against them was inappropriate and that, in this case, he wasn’t following ‘established procedures’?

‘Drive,’ commented one online reader in response to CNN’s coverage of the story, ‘and, if you cannot, then consider flying in a cramped seat with surly airline employees treating you like animal-cargo.’

When anyone complains, they are reminded – whether by Warren Buffett or fellow travellers – that they cannot expect commercial flight to be as it was in the days of silver service, adequate legroom and well-spoken, Grace Kelly–lookalike stewardesses with impeccable manners.

What has changed is the way in which, as perceived by the majority of passengers, airlines have abandoned, along with common decency, any notion of the romance or poetry of flight. For Michael O’Leary, the never-less-than-controversial CEO of the European budget airline Ryanair, passengers are in cahoots with this change: ‘Most people just want to get from A to B. You don’t want to pay £500 for a flight. You want to spend that money on a nice hotel, apartment or restaurant… you don’t want to piss it all away at the airport or on the airline.’ Of Ryanair, he says: ‘Anyone who thinks [our] flights are some sort of bastion of sanctity where you can contemplate your navel is wrong. We already bombard you with as many in-flight announcements and trolleys as we can. Anyone who looks like sleeping, we wake them up to sell them things.’

For O’Leary, the romance of flight has long been in the grave, where it deserves to rot. ‘Air transport,’ he told BusinessWeek Online in 2002, ‘is just a glorified bus operation.’ As Alfred E. Kahn, the American economist who became known as the ‘father of airline deregulation’, had said a quarter of a century before: ‘I really don’t know one plane from the other. To me they are just marginal costs with wings.’

Robert L. Crandall, the president and CEO of American Airlines from 1985 to 1998 and a fierce critic of deregulation, called the airline industry ‘a nasty, rotten business’. And Al Gore, back when he was vice president of the United States, stated: ‘Airplane travel is nature’s way of making you look like your passport photo.’

If they (or their employers) can afford it, passengers can, of course, fly in anodyne, faux-posh first class. And yet, to echo O’Leary’s thinking, who – unless they are travelling on expenses – would want to fritter away thousands of pounds on a first-class ticket now that the very concept of ‘first class’ no longer means what it did in decades gone by?

On and off, for more than a decade, I have ridden Liverpool Street to Norwich expresses. These trains have long been busy, to the point in recent years where standard-class passengers who are paying through their noses are forced to stand for long distances. When supplementary fares were available on weekdays, I’d ‘upgrade’ to first class.

It wasn’t so many years ago that these trains offered breakfast, dinner, lunch and tea. Paper tablecloths might have replaced linen at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and silver cutlery may have been a thing of the distant past, and yet there was still something of a half-remembered air of first-class travel in these East Anglian dining cars. By the second decade of the century, the restaurant cars had gone. And so what on earth – or in Greater Anglia – was the point of first class?

When I lived in the Scottish Highlands, I’d drive south to Inverness to take the Caledonian Sleeper to London. The sleepers were time-worn, yet clean and well maintained. The Scottish stewards were cheerful. The bar car was fun, with a varying cast over the seasons of MPs and lairds, fishermen, artists and writers, doctors, lawyers, engineers, oil riggers, architects, and American and Japanese tourists. Although not first class in a contemporary ‘top celebrity VIP’ manner, the Caledonian Sleeper had the charm and elan of a less-bullish era.

But while waiting at Euston for the staff of the return Caledonian Sleeper to let waifs and strays like me on board, the best option was always to perch on a luggage trolley or lean against a column on the bare concrete platform and read. Even on the coldest winter evening, that utilitarian platform was – to me at least – more first class than the Hieronymus Bosch-style ‘First-Class Lounge’.

Many of the journeys I’ve made in Britain and around the world have been by penny-plain and matter-of-fact boats, trains, planes, taxis and hire cars. By foot and on bicycle, too. It hasn’t mattered that a train or ferry has been spartan, if the scenery, people, weather or occasion itself has been special. These, though, have been very different journeys to those made by forms of transport in which passengers are synonymous with cargo, and when our sole interest appears to be to get from A to B as cheaply and as quickly as possible.

One of my favourite books since I first read it in a public library as a child – I then bought a second-hand copy in a Brooklyn bookstore years later – is Charles Small’s Far Wheels. Published in 1955, it evokes the steam railway journeys that Small made while working for the American oil industry in the Congo (the Chemins de fer du Kivu, ‘a 60-mile narrow gauge streak of rust’), Madagascar, Mozambique, Fiji, Jamaica, the backwaters of Japan and blazing East Africa.

I have wanted every place I have been to – whether the Aleutian Islands or Zennor, Doncaster or Dimapur, Lecce or Llandrindod Wells, Zapopan or Arnos Grove – to be particular and special. Far too much twenty-first-century travel is homogenous in character. It is now possible to travel more or less around the world by more or less identical Boeing or Airbus jets from one more or less identical airport to another, to stay at the same chain hotels, and to ride the same high-speed trains on dedicated tracks – as travel by picturesque regional railways declines – and to eat identical food at the same chain restaurants while wearing the same clothes as pretty much everyone else.

I mentioned the East Anglian main line from Liverpool Street to Norwich. From 2019, its express services have been run not by individual class 90 electric locomotives and their trains of British Rail Mark 3 coaches, but by flavourless – if hopefully efficient – electric multiple units. What I’ll lament when I use these trains is not so much the fact that, in terms of rolling stock, an old order is yielding to new – all things must pass – but a further loss of a regional identity. In recent years I have been spun down this line by trains pulled by Sir John Betjeman – former Poet Laureate, champion of railway heritage and once an assistant editor at the Architectural Review – as well as ViceAdmiral Lord Nelson, Royal Anglian Regiment, Colchester Castle and Raedwald of East Anglia.

Some time in 2016, Raedwald of East Anglia – named after the seventh-century Saxon king buried in the ghost of the longship excavated at Sutton Hoo in 1939 – returned from overhaul without its nameplate. When I asked passengers waiting for an express train at Ipswich station one morning if they were sorry that Raedwald of East Anglia’s name had gone missing, most, even if friendly, looked at me blankly. No one I spoke to had noticed. Many had no idea the locomotives had names.

The stories in this book begin in the 1930s, because it was this decade that saw transport raised from a service and engineering skill to something of an art in every which way, from the design of the machines themselves to the posters, promotional films, and associated poetry, architecture and music. The 1930s are commonly thought of as the ‘Golden Age of Travel’.

But later decades offered journeys that have mattered, too. They exist today for all classes of travellers on board Japan’s latest bullet trains, which get better by the decade; for those living on the outskirts of Dresden in Germany, who are served on the way to work or school by characterful narrow-gauge steam railways; and for those who ride the 1930s trams that are still very much a part of the streetscape and civic culture of fashion-conscious Milan.

Aside from its clarion call – all journeys should be special; all journeys should truly matter – this is a book for those who want to know what journeys by the great ocean liners, airships, express trains and airliners were like in decades beyond our reach. It is a book, too, for those in search of the world’s most romantic transport byways, from the Atlantic coast of Donegal to the Red Sea port of Massawa. It shows, I hope – and despite insistent propaganda to the contrary – that not only is the journey far more than a way of getting from A to B, but that today, as it has been in the past, it can be a more rewarding experience than either the point of departure or arrival.

What was it really like to take the LNER’s Art Deco Coronation streamliner from Edinburgh to King’s Cross; to cross the Atlantic by SS Normandie; to fly with Imperial Airways from Southampton to Singapore; to steam from Manhattan to Chicago on board the New York Central’s 20th Century Limited; or to dine and sleep aboard the Graf Zeppelin airship? What did people eat and drink? What did they wear? How did they behave? What were their expectations? How safe were they? What did these journeys sound like? How did they smell? And what about washrooms and lavatories?

Recreating these journeys allows me to explore the history of routes taken and the events – social and political – enveloping them, and to find out what has happened to them since. This book contains the stories of the machines that made these journeys possible, of the people who shaped them, and of those passengers, too, who played key roles in modern history – like Le Corbusier, who flew to Rio on Graf Zeppelin to forge the transatlantic link between European and nascent Latin American Modernism.

The journeys I have written about fall within the period 1932 to 2005. I have connected them to specific dates and told their stories in the first person. The final five journeys are those I have made in real life. The 15 twentieth-century journeys are those that I have dreamed of making, and I have written them as if I had made them myself. I have often lulled myself to sleep in strange hotels, or when my mind is overactive, by imagining what it must have been like to ride the Coronation Scot from London to Glasgow in the late 1930s – from the bus, Underground or taxi ride to Euston and that terminus’s famous Doric arch and Great Hall, to the train itself. What would the food served in the restaurant car have been like, and what about my fellow passengers? What would I have seen from the train’s windows as I travelled through a countryside still farmed by horses and steam traction engines, between fleeting glimpses of smokestacks and coal yards and factories? And what of Shap Fell, free of the scourge of the M6 barging its impolite way alongside the railway; and of the arrival in pre-war Glasgow, where mighty factories built locomotives for export around the world, and shipyards, mightier still, welded and riveted the freighters – alongside opulent ocean liners – that took them there?

I cannot be sure, of course, of who exactly I would have been had I been born shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, although I have a feeling that one way or another my historic persona might well have been involved in the development of military aircraft between the wars, fought in the Second World War, and then led a busy life as the economies of the free world boomed and new technologies offered journeys to the Moon and looked to the stars.

Although certain ways of seeing the world – along with language, dress, measurements and manners – have changed since this past self rode the Coronation Scot and flew on GrafZeppelin from Germany to Brazil in the 1930s, his enthusiasms are very much my own. I have tried, as far as possible, to avoid hindsight, so that the narrator can only ever have an inkling of what the future might hold as he journeys through Europe, Asia and the Americas, during eras of both optimism and nagging fear.

My narrator shares journeys with characters drawn from my imagination. He also meets real people – I have tried to imagine what it might have been like for example to meet the American industrial artist Henry Dreyfuss on board the peerless 20th Century Limited, for instance, and I have brought historical characters onto trains and planes and airships who may or may not have been on that exact trip at that precise time. They allow me to explain more fully why certain journeys mattered technically, socially, aesthetically, commercially and politically.

There are many other journeys I have dreamed of making – and, equally, many more I have taken and plan to go on. But, if told here, they would burst the finite boundaries of a book as they raced out to all points of the compass, in plumes of steam and vapour trails, the surge of spirited machines ‘coming on cam’, and the steady pulse of ships’ engines under skies near and far.

*

NB: I use metric measurements only when an Englishman of the times would have.

ONE

Londonderry to Burtonport: Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway

4th–6th October 1932

China has been all the vogue this year. Shanghai Express, starring Marlene Dietrich, set the pace in the popular imagination, while my fellow undergraduates Alec and Archie have just returned from a summer in Manchuria, which is pretty daring of them, not least because the Japs have created a puppet state there they call Manchukuo. I learn of Alec and Archie’s adventure over a teatime meal in Soho at the Shanghai Restaurant on Greek Street. Over plates of crab fried rice and what the menu calls chup suey, washed down with a bottle of rice wine and pots of oolong tea, we wonder if any of us has been anywhere more exotic than Manchuria.

‘Well, I’m off to Burtonport tonight,’ I say.

‘Where they brew Burton beers? Sounds very exotic,’ snorts Archie.

‘No. Burtonport, a fishing village on the far Atlantic coast of Donegal, the last stop on the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway.’

Between us, we know countries as far flung as India, Ceylon and China, yet agree that surely nowhere could possibly be more exotic than Burtonport, and that I am to report back its wonders over Guinness and Jameson.

I walk up to Euston only just in time to board the Stranraer sleeper. By chance – or good luck – I have a third-class berth to myself, in a comfortable former London and North Western Railway 12-wheeled sleeping car. Even though we set off just before 8 p.m., I am fast asleep soon after the gently swaying train has passed Watford, and only wake up when we pull into Carlisle in the early hours of the morning. Keen to find out which locomotive has taken me this far, I slip my coat over my pyjamas and my bare feet into brogues, and walk between pools of lamplight and wafts of steam from the train’s heating pipes towards the bulldog silhouette of 6122 Royal Ulster Riflemen. Built five years ago at the North British Locomotive Works in Glasgow, this is one of the London Midland and Scottish Railway’s (LMS) powerful Royal Scot 4-6-0s. Her large boiler, crowned with the squattest of chimneys, gives her a truly massive, hunched-up appearance.

If he had been able to get his own way, Henry Fowler, chief mechanical engineer of the LMS would have built a longer – if only slightly leaner – class of four-cylinder compound Pacifics, based on the latest French practice, instead of the three-cylinder Royal Scots. Fowler’s Pacific, which never got beyond the drawing board, was seen by management as being too expensive a proposition, and probably a little too exotic for the conservative tastes of Derby works. The Royal Scots were built instead, and in a rush, by North British – in association with Herbert Chambers, the chief draughtsman at Derby. They might not be Pacifics – nor, I gather, as efficient as the latest French compounds – but the Royal Scots are potent and reliable machines.

As Royal Ulster Rifleman steams away to be serviced at Upperby shed, I watch a pair of smaller locomotives, coupled together, backing towards the sleeper. The train engine is 40936, a brand-new LMS 4P class compound 4-4-0 – resplendent, like Royal Ulster Rifleman, in gold-lined crimson lake paintwork. The compound’s pilot, in the same livery, is an engine new and exotic to me: 14672, a lithe and handsome 4-6-0. Her works plate tells me she was built in 1911 by North British, for the Glasgow and South Western Railway. I have to ask her driver, amused to see me on the platform at this unsocial hour, what this elegant engine is. One of Mr James Manson’s express locos, this is her last month in service. The engine is in fine shape, but the LMS is standardizing its fleet.

Unable to get back to sleep, I open the ventilator above my window to listen to the locomotives as they pound northwest from Carlisle, over the border and on through Dumfries, Castle Douglas and Newton Stewart, on the undulating line to Stranraer, 73 miles away, where we pull in at 6 a.m. The ferry across the Irish Sea to Larne is berthed right alongside us. On the platform I observe my fellow passengers. They include a sizeable contingent of what must surely be businessmen, politicians and civil servants, some hanging on to their hats and dignity as the wind scudding across Loch Ryan blows away morning cobwebs and English trilbies and bowlers. This is the shortest of the Irish Sea crossings – just 45 miles and two and a half hours – and much the favourite for those lacking sea legs.

Our ship is the handsome new Princess Margaret named after the younger daughter of the Duke and Duchess of York. I have details of her – the ferry, that is – in my bag. Here they are. Built by William Denny of Dumbarton for the LMS and launched last year, she weighs 2,523 tons and can carry 1,250 first- and third-class passengers, 236 cattle, 37 horses and a sizeable amount of cargo. I think the cattle must come from Ireland as I don’t see any boarding here at Stranraer. No horses either. Princess Margaret, I read, is powered by a pair of Parsons steam turbines producing a combined 7,462 shaft horsepower at 269 rpm. Her top speed is 21½ knots.

I make my way to the cafeteria for breakfast, as members of parliament and officer ranks of the Civil Service remain tucked discreetly behind the doors of their first-class cabins. We slip anchor at 7 o’clock – sunrise – steaming smoothly from the loch. On deck, I listen to the stern hiss of water along the sides of the ship as she cuts into the Irish Sea. At her stern, I watch water churned into furious channels of foam and spray.

I find myself inwardly singing along with Bing Crosby’s ‘Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)’, which somehow segues into Duke Ellington’s ‘It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)’. The sea certainly swings, turning decidedly choppy. I retreat to the dining room. A well-dressed, unfazed English family at the next table tucks into an ambitious breakfast. The son is engrossed, between mouthfuls of scrambled egg and bacon, by the latest copy of The Magnet, and its slightly incongruous stories of Billy Bunter on the one spread and exotic travels through the empire on the next. I can’t help noticing that the cover features an illustration of the Great Western Railway’s Cheltenham Flyer, the world’s fastest scheduled train.

His sister is reading The Girl’s Own Paper, and their mother, dressed in well-cut tweeds, lights a cigarette. On the table, she has a copy of Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons, a novel published last month that’s said to be very funny. If I hadn’t fallen asleep, my own reading for the Stranraer boat train was to have been Freeman Wills Crofts’ Sir John McGill’s Last Journey, the story of a Northern Irish industrialist murdered, apparently, on the Stranraer sleeper. A part of the attraction, for me, is that Crofts is a retired civil engineer with the NCC (Northern Counties Committee, the Northern Irish division of the LMS) turned detective fiction writer.

I very much enjoy bobbing about on water, but Stranraer and our Charlie Chaplin’s Gold Rush–style meal, our plates sliding from one side of the table to the other, are soon memories as we head into harbour at the head of Lough Larne. Out on deck, I can see gulls screaming, terns wheeling and cormorants skimming across the waters. I glimpse emerald fields over the rooftops of terraced dockside houses, as well as railway yards, cranes, warehouses and squat, glum-looking churches.

And there, on the other side of the NCC tracks for Belfast, is, to my English eyes, a wonderfully exotic sight. A purposeful 2-4-2T narrow-gauge tank engine, crimson lake liveried, is waiting at the head of a train of three corridor-connected coaches that look like the latest LMS main-line designs shrunk to fit the NCC’s narrow-gauge lines. I beetle down to this train from Princess Margaret as quickly as I can, as do those few businessmen and civil servants not heading for Belfast, and the English family.

What a fine and unexpected train this turns out to be. Aside from its compelling engine, 104 – a two-cylinder compound designed by Bowman Malcolm, locomotive superintendent of the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway and built at York Road, Belfast in 1920 – it is very smart indeed. The four-year-old carriages boast steam heating, plush upholstery, and lavatories, too.

This is the Ballymena and Larne boat train. With three stops along the 3-foot gauge line, we’re scheduled to run the 25 miles to the junction for Londonderry at Ballymena in 64 minutes. While the Cheltenham Flyer takes only a minute longer to run the 77 miles from Swindon to Paddington, the narrow-gauge Irish train is not slow considering the terrain. After easing our way around the harbour and then away from the stop at Larne Town, 104 gets quickly into her efficient compound stride. The first 12 miles of the trip prove to be an arduous climb through beautiful green farmland fringed with purple hills with gradients as steep as 1-in-36. We crest the ascent at Ballynashee, 600 feet above sea level.

Accelerating rapidly, we are now running at over 30 mph as we head south-west to Kells – and, from there, north at a clip to Ballymena, where we join the main line from Belfast to Londonderry. At Ballymena, our driver tells me that we’re lucky to have 104 on the run today. The boat train is very often in the hands of one of the ungainly Atlantic tanks built by Kitson & Co. of Leeds in 1908. Nominally more powerful than the compounds, these are prone to slipping – making something of a misery of the long climb up from Larne in wet weather, which is commonplace here, of course. One of these 4-4-2 tanks is at work shunting a string of goods wagons while we chat. The rest of the compounds run the Ballycastle to Ballymoney line further north. ‘But,’ says the driver, ‘we’d sure like them back on the Ballymena.’

I can’t help noticing that the English children waiting on the Londonderry main-line platform are eating Mars Bars, a new tuppenny chocolate bar made in a factory in Slough passed every day, at speed, by the Cheltenham Flyer. But here comes our Derry flyer heading into Ballymena station, a smart seven-coach corridor train led by a brightly polished NCC 4-4-0. This is U2 class No. 74 Dunluce Castle, one of the ‘Scotch engines’ built in 1924 by North British of Glasgow. She is clearly modelled on a Midland or LMS 2P 4-4-0, although William Kelly Wallace, locomotive engineer and civil engineer of the NCC from 1922, supervised the design. Only recently, Mr Wallace introduced colour light signalling – the first in Ireland – at Belfast York Road, the terminus from which Dunluce Castle departed earlier this morning.

The other thing I can’t help noticing is the width of the NCC track. Irish main lines adopted the 5-foot, 3-inch gauge, rather than the standard 4-foot, 8½-inch mainland gauge. I find this particularly interesting because I attended a lecture in Oxford earlier this year given by a Harvard archaeologist who has been researching the paved and grooved trackway the ancient Greeks engineered across the Isthmus of Corinth in around 600 BC. This trackway enabled ships, and perhaps even fighting triremes, to be pulled for five miles overland between the Ionian and Aegean seas, saving a great deal of time. This early form of railway was in use for 650 years, and Aristophanes refers to it in his comedy Lysistrata. The distance between the grooved tracks was exactly 5 feet, 3 inches. Irish railways have a classical pedigree.

The Londonderry train gets into a 60 mph stride before stopping at Ballymoney, where I lean out of the window to watch a pair of 3-foot-gauge S class compound 2-4-2Ts at work. Our next stop is Coleraine, where passengers can change for Portrush and the Giant’s Causeway Tramway. I would do so if I had another week in hand, but exotic Burtonport calls, and it’s still a long way off. It’s midday now as we cross the River Bann, and, as if by sleight of hand, the scenery changes from the engagingly bucolic to the stirringly romantic. It’s as if the poet Coleridge were in charge of the landscaping. Skirting the left bank of the Bann, we steam towards Castlerock and between the two tunnels – the longest in Ireland – passing below and through the former estate of the eighteenth-century Lord Bishop of Derry, the Suffolk-born Frederick Hervey, Earl of Bristol.

Between the tunnels, I stretch my neck up to see the Mussenden Temple, an exquisite classical rotunda overlooking the North Atlantic. I know from my interest in architecture that its design is based on Bramante’s Tempietto in Rome, itself based on the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, which I cycled to along the Via Appia only last year. The architect of Bristol’s Irish tempietto was most probably Michael Shanahan, who accompanied the eccentric and philanthropic earl on at least one of his many visits to Italy.

The tempietto is, in fact, a library, commissioned in 1783 as a wedding present to Bristol’s favourite cousin, Frideswide Bruce, who married Daniel Mussenden, an elderly London banker. Said to be Bristol’s lover, she died in 1785. The inscription around the building, which I know – but cannot possibly see, of course, from the train at 30 mph – reads:

Suave, mari magno turbantibus aequora ventis

e terra magnum alterius spectare laborem

[’Tis pleasant, safely to behold from shore

The troubled sailor, and hear tempests roar]

I know, from Latin classes at school, that this is a quote from Lucretius’s De Rerum Natura, but what it means here on the Atlantic coast of Ulster, I have no idea.

We canter down to the white sand beaches of Benone Strand, our track right by the rolling, white-horse ocean – I see either dolphins or porpoises revelling in the swell of the sea – and with the long looming crags of Binevenagh Mountain shadowing our progress inland.

Cutting off Mulligan Point, we lope past Bellarena station and find ourselves alongside water again, crossing a bridge over the River Roe and skirting Lough Foyle. On through farmland, we rumble over a further bridge across the River Faughan, and – following the curves of the banks of the River Foyle into Londonderry – come to a stand under the glazed roof of the NCC’s Waterside station, a sandstone building designed, my notebook tells me, by John Lanyon, a prolific railway architect and engineer. Dominated by a muscular Italianate clock tower, it opened in 1875.

Now my naivety shows. I have come this far, and without lunch, without knowing where the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway terminus is, nor the times of trains to Burtonport. I ask at the stationmaster’s office. There is an afternoon train to Burtonport, I’m told, leaving at 4.45 p.m. The Swilly’s Graving Dock terminus is a mile or more’s walk north, on the other side of the Foyle. The timetable says it arrives in Burtonport at 9.20 p.m., but what with uncertain weather and wagons to shunt on the way, it could well be a little later. As the sun sets at 7 p.m. at this time of year, I realize this will mean at least two and a half hours in gloaming and then darkness.

‘And, you should know, there’s no lighting or heating on the Swilly trains.’

This sudden Home Counties accent belongs to the well-dressed mother who, with her children, has come to Londonderry on the same trains and boat as me. ‘It’s a rather beautiful trip in the summer, but eventful at other times of year,’ she continues.

I introduce myself and ask if she and her children are off to Burtonport, too.

‘No. Creeslough. We stay at the Rosapenna Hotel. It’s where my husband insists on going whenever he’s back from India. He fishes for salmon and plays golf there to unwind, and we all like the sandy beaches nearby. The children have permission to be out of school to see their father.’

‘Army?’ I ask.

‘No. Architect. Working on New Delhi. Inaugurated last year, of course, but the work goes on. Anyway, I wouldn’t advise the afternoon Burtonport. It could well be late. We’d arrive in the dark and it’s been a long trip from Surrey for the children. The morning train leaves at 7.30, so it’d be best to stay the night here.’

If any of us was sufficiently determined, we could be in Burtonport tonight – and, all going well on the Swilly, in just a little over 24 hours from Euston.

‘I’ve booked two rooms at the Metropole on Foyle Street on the other side of the bridge. You’re welcome to have one of them. I can always share with the children.’ It’s a more-than-generous offer. ‘If you plan to wander around town, I can take your bag on to the hotel. Why not meet us for supper at seven?’

Tucking away a cheese and pickle sandwich and a strong cup of tea in Waterside station’s refreshment room, I find myself with an afternoon to spare in this busy town split in two by the dark and fast-flowing Foyle. Remembering that another of Ireland’s narrow-gauge railways, the County Donegal, runs trains from the city, I ask where the station is only to find that Victoria Road is just a few minutes’ walk south of Waterside. Looking out for a small red-brick station building, I spot a black main-line locomotive steaming slowly along with a rake of coaches on the other side of the river. This, I think, must be a Great Northern train from Dublin. What a railway mecca Derry is proving to be, with four terminuses – three within easy walking distance – served by four railways, two of them narrow-gauge.

Victoria Road is a modest yet well-designed and neatly built station, reached from the road through a sloping timber and glass-covered walkway. Its architect was James Barton, a long-lived engineer who was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, and devoted much time in his busy career plotting a railway tunnel under the Irish Sea between Larne and somewhere in Scotland. Stranraer, perhaps. If he had succeeded, trains would have run directly all the way from Belfast via Glasgow and London.

Serving two tracks, the Victoria Road platform is half enclosed by an iron, glass and timber canopy adorned with decorative mouldings and revealing stirring views along the Foyle. The County Donegal timetable promises a train to Strabane, 14½ miles and just over an hour away, at 2 p.m. I book a return ticket. And here she comes now, backing into the platform – three oil wagons and one, two, three red-and-cream eight-wheeled coaches. The locomotive is a handsome black 2-6-4T, No. 20 Raphoe, built, says the plate on her side, by Nasmyth Wilson & Co., Patricroft, Manchester, 1907.

I ask Raphoe’s driver about the locomotive and train as he oils her Walschaerts valve gear.

‘Raphoe. Well, it’s a town in Donegal with a castle and a stone circle they say is older than Stonehenge. This is a class 5 tank. She’s a darling to be sure. The oil wagons? They’re for the fishing fleet at Killybegs, the biggest fishing port in all of Ireland. We drop them off at Strabane, and another Donegal train takes them on to Killybegs itself. A long way? Seventy miles and more.’

My keenness earns me a footplate ride – but not from Victoria Road, where I would be seen by a railway official. ‘Come up at New Buildings. It’s the first stop.’

A bustle of housewives weighed down with shopping crowds into the narrow-gauge carriages, and with the wave of a flag and the shriek of a whistle, we accelerate out of the terminus and rattle along the banks of the Foyle to New Buildings, by which time Derry has disappeared from view. At the station, I’m up from my wooden seat and on Raphoe’s footplate quicker than anyone can say Jack Robinson. Luckily for me, the cab is polished and as clean as a steam locomotive can be. With steam pressure at 175 pounds per square inch and her safety valves beginning to lift, Raphoe is off again, rocking gently as we nudge over what must be 30 mph along a track sewed neatly between rolling fields and pastures.

We whistle for Desertstone Halt (‘Stops when required’), our call answered only by a brittle chorus of circling jackdaws, and trot on through countryside that appears idyllic, although I have no idea how the Depression has affected these parts. I say to the crew that Donegal is a beautiful part of the world. ‘It is indeed,’ replies Michael, the fireman, ‘but this is Tyrone. A funny thing it is, to be sure, but Donegal’s on the other side of the river. But we’ll get there by and by.’

We do. All too soon, I swap the footplate of Raphoe at Ballymagorry for a busy carriage, all chatter and laughter. Ten minutes later we rumble over the Great Northern main line from Derry to Enniskillen, cross the River Mourne and draw into Strabane under lowering clouds. What a remarkably active station it is, with a host of red tank engines in steam and trains for distant Letterkenny, Glenties, Donegal, Killybegs and Ballyshannon. The County Donegal, I’ve been told, is the most extensive narrow-gauge railway in the British Isles, with, I think, lines extending to 124½ miles – 110 of them in Donegal. The county itself is across the border in the Irish Republic, just beyond Strabane station.

I’d love to explore further, for the County Donegal is evidently an extraordinary thing, a busy rail system far removed from the lonely little railways of Wales I explored last year – and, I don’t doubt, very different from my holy grail, the Burtonport extension of the Londonderry and Lough Swilly. I have just 20 minutes to enjoy this narrow-gauge cornucopia, complete with a curious new diesel railcar growling out for Glenties, before Raphoe is whistling up passengers for the return 3.30 p.m. to Derry. Rather than oil tankers, we have four goods wagons in tow, stacked with all sorts of Donegal produce bound for Londonderry.

It’s raining as I leave Victoria Road back in Londonderry and scurry across the Carlisle Bridge, an impressive iron-framed affair from the early 1860s. It has road traffic above and railway tracks below, for the transfer of wagons between the Great Northern and NCC. On the far side of the bridge is Foyle Road station, a squat brick building with arched windows and openings, and what appear to be papal emblems on the peaks of its twin towers. I stop under the entrance arch to check my architectural notes. The station was designed in 1870 by a Mr Richard Williamson, surveyor and engineer, who had teamed up some years earlier with the Glaswegian architect Thomas Turner. In April 1874, Mr Williamson went to London to give evidence to the House of Lords on the Londonderry Port and Harbour Bill. Drenched on the Steam Packet crossing to Fleetwood in Lancashire, he developed bronchitis and died that month at Euston station’s Victoria Hotel.

Out on the platform, I’m rewarded with the cheering sight of two brightly polished black Great Northern locomotives. One is 198 – one of the mixed-traffic U class 4-4-0s built in 1915 by Beyer Peacock of Manchester – at the head of a stopping train for Enniskillen. The other, simmering quietly alone on the opposite platform, is a brand-new three-cylinder compound express passenger V class 4-4-0, No. 85 Merlin. This impressive new engine has been built for fast trains between Dublin and Belfast. Perhaps she’s here on a diplomatic mission, touring the Great Northern. Officially, she’s too big for the line. The crew must be taking tea. I step gingerly onto her footplate, noting the boiler pressure gauge’s redline of 250 pounds per square inch, the same high figure as an LMS Royal Scot.

Both Irish locomotives are designs by Colonel George Tertius Glover, locomotive engineer of the Great Northern. I’d dearly like to see more of them, especially in a colour other than black, but it’s 5 p.m. now and I must get to the Metropole and bathe before supper.

My high-ceilinged room is on the first floor of this grand classical building. A small ironwork balcony offers views up and down the teeming street. Washed and groomed, I join my friends in the dining room.

Over cutlets, I explain why I’ve come in search of Burtonport, and how Archie, Alec and I agreed that it must surely be a more exotic location than Manchuria. Mrs Moore, it turns out, is related – as are Archie and Alec – to Lord Lytton, the former governor of Bengal, who went out to Manchuria recently to report for the League of Nations on Japanese aggression there. So we have much to talk about, and even more when Mrs Moore proves to be related to Sir Edwin Lutyens, architect of New Delhi. I plan to go there next year after finals.

Mrs Moore is quite the exotic herself. She’s taken up flying lessons and says, apropos of Derry, that only this May the American aviatrix, Amelia Earhart, landed in a field at Culmore – just north of the city, on the banks of the Foyle – at the end of her record-breaking transatlantic solo flight at the controls of a high-winged Lockheed Vega 5B.

‘She was hoping for Paris, like Lindbergh,’ says Mrs Moore over a nightcap, as her children, Maude and Philip, play round after round of Snakes and Ladders. ‘Must have been low on fuel. She’d certainly have got a better meal there.’

I’m keen on airplanes, too, and plan to spend time at aerodromes once free of the groves of academe. We imagine how, one day, we’ll be able to cross the Atlantic in ‘airliners’, all cocktails and silver service, and how very slow the epic journey to Swilly will seem. We retire early, as we’ll need to be up and about early for the Burtonport train.

The hotel packs us a picnic breakfast and lunch, complete with a Bakelite Thermos flask filled with hot tea. Until 1919, a horse tram ran from Foyle Road station to the Swilly’s Graving Dock terminus. I choose to walk. The hotelier drives Mrs Moore, Maude and Philip there in a polished Austin 12. As I walk, I’m savouring the moment.

I’ve read enough about the Swilly to know that the 50-mile Burtonport extension is widely considered something of a white elephant. Opened as recently as 1903 with government help in order to provide employment in the ‘congested areas’ where poverty and large families have conspired against a decent life – the lack of which has prompted further emigration to America – its main goal and final destination was the fishing port at Burtonport. A railway would bring fresh fish to Londonderry, and on to London restaurants. The wild landscape, though, meant that there was never going to be an easy way for the line to reach the fishing port on the Atlantic coast. It makes its way across a largely uninhabited landscape, with stations sited miles from the villages they purport to serve. Over the past three decades, money has been tight, and the operation, it’s said, is run on the proverbial shoestring.

My first sight of Graving Dock terminus, under a low-hanging and drizzly sky, appears to confirm the rumour. I almost mistook it for some rundown mechanic’s workshop. Inside, its two dingy platforms are set between rough-hewn walls. Busy, though. On one platform is our train, comprising four grey compartment carriages mounted on twin bogies, with the same number of four-wheeled wagons behind them. On the other is a five-coach passenger train sitting behind a glossy black and well-proportioned 4-6-2 tank engine: No. 10, built by Kerr, Stuart & Co. of Stoke-on-Trent, the company Mr Mitchell, designer of last year’s world airspeed record-breaker, the Supermarine S.6B, was apprenticed to before taking off from Stoke to Southampton, to the sea and the skies. The train is the 7.15 to Buncrana and then Carndonagh, a seaside town on the Inishowen peninsula popular in summer.

As No. 10 steams away from the claustrophobic station, which a porter tells me was built as a goods shed in the early 1880s, Mrs Moore, Maude and Philip come down the platform looking for a first-class compartment. ‘We’re going up in the world today,’ says Mrs Moore. ‘It’s a long trip, and I was told that third class is wooden seats only.’ We peer inside the grey coaches. Third class is indeed very basic. ‘Like grooms’ quarters on a Southern Railway horsebox,’ she says.

First class boasts faded upholstery. It looks dusty.

As we weigh up the delights of these pallid carriages with their matchwood flanks, a second glossy black locomotive backs down to join our train. We all march up to see her, a magnificent 4-8-0 tender engine. It’s No. 12, built by Hudswell, Clarke & Co. of Leeds in 1905, her side rods picked out in red. We clamber aboard the train as last-minute packages and post are shut into the vans.

‘NEXT TO SAFETY’, reads a slogan on the platform timetable opposite our window, ‘PUNCTUAL RUNNING OF TRAINS IS MOST IMPORTANT’. On the dot of 7.15 a.m., we pull slowly away from Graving Dock and cross a road at the statutory 8 mph indicated by a trackside sign, where I catch sight of the railway’s extensive Pennyburn works. Sliding down the window on its leather holding strap, I lean out to gawp at one of the Swilly’s imposing 4-8-4 tank engines, said to be the most powerful locomotives at work on narrow-gauge railways in the British Isles. I must invest in a camera. I wonder how much the new 35mm Leica costs?

The driver opens up the big 4-8-0. We head across marshy country to the border post at Bridge End. We stop, but only very briefly, as if passed through with a nod and a wink. We stop again just over a mile away, to pick up post and a solitary passenger at the tiny village of Burnfoot, before threading slowly along a bank to a station set between the Skeoge and Burnfoot rivers. Inaccessible by road, this is Tooban Junction. Buncrana and Carndonagh trains heading north branch off here, while we swing south-west.

Just inland from Drongawn Lough, an Irish fjord off Lough Swilly – all deep water, swans and greylag geese – we climb a 1-in-49 grade through a deep embankment to a stop at Carrowen. My railway map of Great Britain and Northern Ireland shows gradients along the line. Mrs Moore is amused.

Along a causeway we cross one of Lough Swilly’s shallow bays before climbing again to Newtowncunningham. It’s ten past eight. We’ve averaged just under 20 mph for this first 12 miles.

With the luxury of a five-minute stop, we investigate our hamper. The strong tea is good, as are hard-boiled egg and ham sandwiches, the soda bread generously spread with creamy butter. There’s a creamery, Lagan’s, at our next stop – Sallybrook, where another wagon is attached to our train. For the next 10 minutes, we writhe north then west through salt flats and mud banks along where Lough Swilly meets the River Swilly. We pick up speed down the 1-in-50 gradient towards Letterkenny, Donegal’s largest town, bucking along at what must be 35 mph.

Here I watch a County Donegal train behind a red 2-6-4 tank engine impatient for Strabane. Maude and Philip prolong breakfast while No. 12’s tender is is topped up with water. A party of black-clad priests and seminarians joins us as another wagon is attached to our train. I know Letterkenny most of all as the place where in 1798 the Irish Revolutionary Wolfe Tone was arrested and then died in unrecorded circumstances after his failed invasion that was supported by 3,000 of Napoleon’s soldiers. The Royal Navy intercepted the French fleet at Buncrana, and that was the end of that.

I know Wolfe Tone’s name from the poem ‘September 1913’ by W. B. Yeats, which first appeared in the Irish Times and was read to us at school, 15 years later, by our English master, Mr Lawrence.

‘Can you still recite it?’ asks Mrs Moore.

What need you, being come to sense,

But fumble in a greasy till

And add the halfpence to the pence

And prayer to shivering prayer, until

You have dried the marrow from the bone?

For men were born to pray and save:

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone —

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.

And then, there’s the verse, I say, with Wolfe Tone:

Was it for this the wild geese spread

The grey wing upon every tide;

For this that all that blood was shed,

For this Edward Fitzgerald died,

And Robert Emmet and Wolfe Tone,

All that delirium of the brave?

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone —

It’s with O’Leary in the grave.

‘But what about the Swilly?’ asks Mrs Moore. ‘Tell me Romantic Ireland’s dead after we’ve passed through Barnes Gap.’

‘Indeed,’ says the heavily tweeded country doctor newly squeezed into our compartment. ‘A most romantic land, but as poor as Croesus was rich.’ He is travelling to Creeslough, 20 miles and an hour or so down the line. When I tell him I’m for Burtonport, he smiles. ‘Do you know how far Burtonport is as the crow flies?’ I say I’ll get out my map. ‘Twenty-eight miles. And how far by the Swilly? Fifty!’ He snorts. ‘A romantic railway indeed.’

‘Why so long?’ asks Philip, freed for a moment from the tyranny of his appetite.

‘There are bogs, rivers, mountains in our way,’ says the doctor. ‘We have to go around them all. It’s an Alice in Wonderland railway. And certainly romantic, although our fellow passengers might not agree, especially not when the thermometer falls, the wind gets up and the rain lashes across the bare countryside.’

Heading south-west from Letterkenny, we follow the south bank of the Swilly through woods and across flats flooded in earlier rain. We call, for small farms and their produce, at Newmills and Foxhall, before turning precipitately north, stopping at Churchill station – just 30 minutes’ brisk walk from the village, says the doctor – and climb at 1-in-50 to Kilmacrenan, 340 feet above sea level according to my map.

‘The village is at least two and a half miles away,’ says the doctor. ‘Day trippers come here from Derry and Letterkenny to visit the Holy Well at Doon and to climb the rock where the O’Connells were crowned kings in centuries gone by.’

The country ahead is rocky and increasingly bleak. We squeeze through Barnes Gap along a viaduct over a road and enter the valley of the Owencarrow. It’s as if a door has opened into a new and strange world. This, surely, is Ireland’s Wild West. We spy the towering white quartz cone of Errigal, Donegal’s highest mountain, some 15 miles to our west; and, closer, the massive bulk of the flat-topped Muckish Mountain.

The track here seems lightly laid, the gradients steep, the curves tight and sudden. So very sudden, in fact, that the line turns near enough a right angle, at 10 mph, to cross the Owencarrow River over a 15-girder viaduct, the rails falling towards this lonely structure at 1-in-50. It levels out only some two-thirds of the way across the river and then climbs again. If this seems a little perilous, perhaps that’s because it is. When gales blow, a common occurrence and something I need to be aware of on my return trip to Londonderry, the Owencarrow Viaduct is closed until the wind abates.

The Swilly can’t be too careful. Just seven years ago, carriages of the afternoon train to Burtonport pulled by No. 14, a 4-6-2 tank engine, were lifted off the track by a westerly gale gusting at 112 mph. One six-wheeler carriage performed a somersault. Its roof gave way and passengers fell into the rocky ravine, 40 feet below. Four were killed and eight injured. The fireman, John Hannigan, ran the three miles to Creeslough as fast as he could in howling wind and driving rain to fetch doctors, priests and other helping hands.

The wind is moderate this morning. Safely over the viaduct, we pull into the curved platform at Creeslough, a passing place for up and down trains, a little less than three hours after leaving Derry. Mr Moore is at the station to meet his family. We are introduced, and before the train departs he offers to make an introduction to Sir Edwin Lutyens at his office on Queen Anne’s Gate. With addresses exchanged and the whistle blowing, I steam off alone, waving goodbye to the doctor, too, as we roll away into this highland Gaeltacht, a land of pre-Celtic gods and early Christian saints who may have been one and the same local deity, then over the shorter and less daunting Faymore Viaduct and into Dunfanaghy Road, six miles from Dunfanaghy itself. We climb hard to a 474-foot summit with sweeping views across Inishbofin to Tory Island out in the Atlantic, and then on to Falcarragh station, a mere four miles from the village.

Cashelnagore, 50 minutes out of Creeslough, follows. The isolated station stands wholly surrounded by the most glorious wild landscape, at once green and rocky and ringed around by mountains. I imagine what fun it might be to be stationmaster here, as far from the madding crowd as it’s possible to be in these islands, and yet with a magical railway on one’s doorstep. We rumble on, braking hard for stray sheep crossing the line, downhill to Gweedore, where we stop for No. 12 to take on water. At Crolly we deliver materials to Morton’s carpet factory, an enterprise that – along with providing local employment – has made hand-woven carpets using local wool for Queen Victoria and King Edward VII.

The final half-hour of this long and eventful run is southwest across the Rosses, a rocky and all-but-treeless landscape of countless lakes and small bays yielding to the Atlantic. A little after 1 p.m., and on time despite warnings to the contrary, we pull into Burtonport station, sited in the port itself and very close to the sea. It’s such a small village, despite the fish sheds, that I’m half tempted to return with No. 12 on the 3.20 p.m. train. But as the rain has set in, visibility is low and the wind is picking up, I head for O’Donnell’s Hotel, where I’ll hole up for the night. I do, though, pop back down to the station with an umbrella to see No. 14, the 4-6-2 tank engine, roll in with the afternoon train.

No. 14 is an hour late. The rain-lashed carriages are barely lit by shadowy acetylene lamps. Passengers are wrapped up like members of Scott’s last Antarctic expedition. At one point, No. 14 had been in danger of running out of water. This had to be brought to the tender from a river, courtesy of a petrol-driven pump stowed in the guard’s van.

What might this trip be like in the depths of winter? Dramatic. Romantic. Wildly exotic.

*

The last trains to and from Burtonport ran on 3rd June 1940. Goods trains with a passenger carriage ran as far as Gweedore until June 1947, but the Swilly gave up the ghost completely in 1953.

There were no buyers for its well-groomed and special locomotives. No. 12 was sold for scrap in 1954, as were the giant 4-8-4 tank engines. Had the railway survived a few more years, it might well have become a focus for preservationists. Today, the ride from Londonderry to Burtonport behind No. 12 would attract enthusiasts and tourists from around the world.

The remains of the Owencarrow Viaduct can still be seen, looking like some ancient monument in a far-distant setting. O’Donnell’s bar in Burtonport is no longer a hotel. Cashelnagore station has been lovingly restored and can be rented as a holiday home. The original Rosapenna Hotel, a timber building designed and made in Sweden and shipped to Donegal, burned down in 1962. Its successor remains popular with golfing folk.

The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway survived as a bus company until 2014. County Donegal Railways trains last ran from Derry to Strabane in 1954, its locomotives painted red since the late 1930s. The entire railway closed to passengers on 31st December 1959, and to goods the following February. No. 20 Raphoe, renamed Foyle in 1937, was scrapped in 1955. Three of her class 5 siblings have been preserved statically.

Aside from a rash of ugly new housing in towns and villages throughout the county, the Donegal landscape remains romantically wild. The county has no railways today.

Londonderry, a major allied naval base in the Second World War, was raided on 15th April 1941 by a single German bomber. There were no further attacks. The Provisional IRA and other paramilitary factions made up for this during the Troubles that detonated in 1968 and were defused for the most part 30 years later, though they continue to flare up sporadically, causing death and destruction.

Long closed, the site of the Metropole Hotel is a car park, and Foyle Street has been butchered by unsympathetic development. Three of Derry’s four railway terminuses have gone. A very basic new Waterside station was opened in 1980. What survives of the Victorian Waterside station is to be redeveloped – again insensitively. Trains still run to Coleraine, Ballymena and Belfast. None stops at City of Derry Airport, despite running past it.

Trains are slower today than they were in 1938, when the North Atlantic Coast Express was booked from Belfast to Portrush – 65¼ miles – in 73 minutes. The same journey, with a change at Coleraine, takes 1 hour and 47 minutes today.

The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) V class 4-4-0 No. 85 Merlin, painted a lovely sky blue in 1934, was preserved after withdrawal from