11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

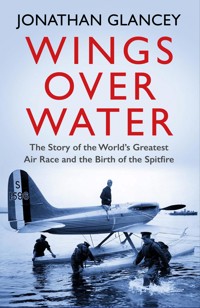

Announced in 1912, the Schneider Trophy stole the imaginations of pioneering aircraft manufacturers in America, France, Britain and Italy, as they competed in a series of air races that attracted a hugely popular following. Perhaps inevitably, the dynamism of rival engineering led to the most potent military fighters of World War Two and Reginald Mitchell's record-breaking Supermarine seaplanes morphed into the Spitfire. Wings Over Water tells the story of the Schneider air races afresh and also examines the wider politics and society of the early twentieth-century that framed the event. It is an exhilarating tale of raw adventure, public excitement and engineering genius.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

By the same author

The Journey Matters

Concorde

Harrier

Giants of Steam

Spitfire: The Biography

Nagaland: A Journey to India’s Forgotten Frontier

Tornado: 21st Century Steam

The Story of Architecture

London: Bread and Circuses

Architecture: A Visual History

Lost Buildings

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jonathan Glancey, 2020

The moral right of Jonathan Glancey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-419-1

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-420-7

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-421-4

Printed in Great Britain

Endpaper image: Supermarine S.6B © Ralph Pegram, 2020.

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Prologue

Introduction: The Wright Stuff

Part One: The Race

Chapter 1The French Connection: 1913–22

Chapter 2The Yanks are Coming: 1923–26

Chapter 3Interim

Chapter 4Winged Lions: Venice, 1927

Chapter 5Chivalrous Sportsmanship: Calshot, 1929

Chapter 6A Very Good Flight: Calshot, 1931

Part Two: The Legacy

Chapter 7The Sea Shall Not Have Them

Chapter 8All That Mighty Heart

Chapter 9A Tale of Two Designers

Chapter 10Aftermath

Chapter 11Sky Galleons

Chapter 12Seaspray

Epilogue: Each a Glimpse

Schneider Trophy Contest Results

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Index

Prologue

At lunchtime on 13 September 1931, a beautiful blue and silver seaplane blazed backwards and forwards over the Solent, a tidal channel between Southampton and the Isle of Wight. From esplanades, from the decks of ocean liners and warships, an audience a million strong watched the aircraft’s unprecedented progress as its RAF pilot, 30-year-old Flight Lieutenant John Boothman, accelerated the Supermarine S.6B monoplane to a mercurial 380 mph. Averaging 340.08 mph over the triangular 217-mile course while pulling G-force turns that brought him close to blackout, Boothman was both the fastest human in history and the winner for Britain of the coveted Schneider Trophy.

To cap Boothman’s triumph, Reginald Mitchell, the aircraft’s designer, installed a more powerful ‘sprint’ version of the Rolls-Royce R (‘R’ for Racing) engine into the wind-cheating S.6B seaplane. Thirty-one-year-old Flight Lieutenant George Stainforth flew this puissant machine on four straight runs over Southampton Water at an average speed of 407.5 mph, hitting an absolute maximum of a shade over 415 mph. No one had flown above 400 mph before. Britain’s latest airliner at the time, the four-engine Handley Page H.P.42, cruised at 100 mph.

Neither Boothman nor Stainforth, nor their colleagues in Britain’s official High Speed Flight (for a spell, T. E. Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia – in the guise of RAF Aircraftman Shaw, was a part of the team), were flying to win the racy – if slightly vulgar – Art Nouveau sculpture that was the Schneider Trophy itself, along with the generous cash prizes. No. What they were competing for was what this trophy meant: international recognition for the world’s fastest, finest and most advanced aircraft, engines, designers, manufacturers, pilots and mechanics.

Announced in 1912 by Jacques Schneider, a wealthy young French steel and armaments magnate – and passionate balloonist and pilot – the trophy stole the imaginations of pioneering aircraft manufacturers on both sides of the Atlantic. Of all the air races initiated in France from as early as 1909, the Schneider Trophy was to be the most coveted. It attracted a glamorous and hugely popular following, whether the contests were held in Monaco, the Venice Lido, the Solent or Chesapeake Bay.

Schneider’s aim had been to encourage a new generation of high-speed civil seaplanes and flying boats that, to him, made more sense than airliners flying over land and cities. In the event, his competition became a driver and celebration of speed and engineering prowess. Because the trophy would be awarded to a national team only when it had won three contests within a five-year span, its rules encouraged long-term thinking about the future of aircraft design and, as it proved, of aviation.

While, ultimately, the British team succeeded – winning the Schneider air races in 1927, 1929 and 1931 – the trophy ignited an enduring passion for sheer technological prowess that saw developments in aircraft design leap forwards.

Because it was so compelling, the Schneider Trophy became a focus not just of remarkable aircraft, daring pilots and swooning public attention, but also of fierce national rivalries. The last three races saw Italy and Britain pitted against one another. Two of the world’s finest aircraft designers – Reginald Mitchell and Mario Castoldi – worked feverishly hard to outdo one another with their exquisite Supermarine and Macchi aircraft. Rolls-Royce and Fiat aimed to produce more powerful and more reliable engines than the other. And, more than these ambitious struggles, two very different political and social systems were set against one another: democratic Britain and Fascist Italy.

Perhaps inevitably, the dynamism of rival engineering led not so much to the advanced commercial flying boats of Schneider’s imagination, but to the most potent military fighters of the Second World War. Mitchell’s record-breaking Supermarine seaplanes morphed, one way or another, into the Spitfire, while Castoldi’s seaplanes led to Italy’s highly effective Macchi C.202 and C.205 fighters.

The Schneider Trophy story is a tale of raw adventure, public excitement and engineering genius, told in a waft of petrol and oil. It is a story, too, of the ambitions of the United States, France, Britain and Italy, and of how France and the US dropped out of the race while Germany – its aircraft industry reined in by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles – was unable to compete, although Dornier made tantalizing designs for Schneider competitors for both the 1929 and 1931 races.

It is a story of mighty engines and larger-than-life characters, from James Doolittle, the barnstorming young American pilot who won the 1925 race and went on to become one of the most daring pilots and distinguished air commanders of the Second World War, to the extraordinary Lady Lucy Houston, a working-class chorus girl who (through advantageous marriages to much older men) became Britain’s richest woman, and without whom Flight Lieutenant Boothman would not have made his victorious flight in September 1931.

Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator, was one of the Schneider Trophy’s most ardent fans, watching the races as he jutted his jaw from the balconies and beaches of the exotic Hotel Excelsior on the Venice Lido. Ardent Fascist Tranquillo Zerbi, a racing car and aircraft engineer, was the brains behind the mighty Fiat AS.6 engine that, though developed too late for the 1931 race, powered the stunning, blood-red Macchi MC.72 with Warrant Officer Francesco Agello at the controls to 440.68 mph in October 1934, setting a piston-engine seaplane record yet to be broken.

Intriguingly, a problem Zerbi had with the carburetion of his AS.6 engine in 1931 was solved the following year by Francis Rodwell Banks, a British high-octane fuel specialist who worked, independently, for Rolls-Royce and Supermarine – a reminder of how, in the face of contrary politics, engineers spoke an international language of development and design, even as Fascism morphed into something very dark and dangerous indeed.

The story of the Schneider Trophy is also one of particular places – not just the contest venues themselves, but also workshops and factories including the spectacular Fiat factory at Lingotto, Turin. An expression of Futurism, a driving intellectual and cultural force behind Italian Fascism, it was here that Zerbi nurtured his prodigiously powerful engines, and cars raced around the remarkable building’s roof as if threatening to launch themselves into the Piedmont skies.

At the heart of the story, of course, are the air races themselves. How these took off. How popular they were. How publicity, the media and art promoted and embellished them. And what happened to air racing – the quest for aerial speed – to seaplanes and flying boats, and to military and civil aircraft design after Britain won the Schneider Trophy for keeps in 1931.

And, inevitably, the story is one of politics. How Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour government did its best to scupper Britain’s chances in 1931, and what this meant for the development of the Spitfire; how America’s governments lost interest in the races, helping to delay the development of effective US fighter aircraft; and how Rolls-Royce engine technology, advanced during the Schneider races, came to Uncle Sam’s rescue in the 1940s.

The last Schneider Trophy race took place nearly 90 years ago, so we can only ever see the contests with our own eyes through black-and-white images: largely grainy photographs taken by cameras too slow to catch racing aircraft, or else scratchy newsreels unable to catch the sound of what would become in the course of the races the world’s fastest and most potent single-seat aircraft. But the races were, in fact, conducted in blazes of colour, not least those of contending machines – pale blue, royal blue, Cambridge blue, gold, white, silver-grey, blood red. One aim of this book is to bring a black-and-white story, which may seem far distant to those brought up in a world of supersonic military stealth jets and jet airliners omnipresent in 30,000-foot skies, into full, high-flying colour.

*

NB: Strictly speaking, the Schneider Trophy events were contests rather than races. They were, though, called races from early on by both the press and the public. In this book, I have used the words where they feel right in context. The same applies to measurements, imperial and metric.

Officially recognized attempts at world airspeed records were made over three-kilometre courses under the direction of time-keepers representing the FAI (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale), the world governing body for air sports founded in Paris in 1905.

In all the books, archives and websites I have consulted, figures and statistics relating to individual aircraft and events – from horsepower to average speeds – tend to vary, as do dates. I have aimed at consistency, but would be interested and grateful to hear from readers citing sources on this subject.

INTRODUCTION

The Wright Stuff

On 17 December 1903, the Wright brothers made the first successful powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine. John Thomas Daniels, a member of the US Life-Saving Station in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, was there to capture the scene with the Wrights’ Gundlach Korona V glass-plate camera. It was the first time Daniels had seen a camera. Orville Wright had positioned it on a tripod immediately before he climbed into the Flyer and made history.

Thankfully, the photograph is remarkably good. Along with the aircraft in the air, piloted by Orville Wright, it shows Wilbur Wright looking on. If he had wanted to, Wilbur could easily have jogged along with the Flyer throughout its 12-second, 120-foot flight. Its average speed was 6.8 mph. The Wrights had tried to engage the US press in the story before 17 December, but there was no interest beyond local newspapers.

The Dayton Daily News covered its bare bones, while the Dayton Evening Herald printed a colourful front-page column telling of a three-mile flight under the headline ‘Dayton Boys Fly Airship’, with the sub-heading ‘Machine Makes High Speed in the Teeth of a Gale’. It was actually a fresh to strong breeze and the Flyer was as much like an airship as a stickleback is like a basking shark. At the offices of an insouciant Dayton Journal, Lorin Wright – Orville and Wilbur’s elder brother – told the story to Frank Tunison of the Associated Press, who turned him away saying the event was ‘not newsworthy’.

In any case, newspaper editors knew that a man could run at 15–20 mph, Henry Ford’s new Model A had a top speed of 28 mph, and American quarter horses grabbing the attention of sports pages across the country at least weekly could gallop at up to 50 mph. And, according to their imaginative reporters, No. 999, a high-stepping 4-4-0 locomotive of the New York Central and Hudson River Railway, had run at 112.5 mph 10 years previously between Batavia and Buffalo at the head of the Empire State Express. While the true speed would have been no more than 86 mph, even that was something to tell the folks back home about in 1893.

The reception given by European newspapers and aviation clubs to reports of the Wrights’ achievement – especially in France – was at best incredulous, at worst arrogantly dismissive. When a letter describing their achievement from the Wright brothers to Georges Besançon, editor of L’Aérophile, was published in the daily sports newspaper L’Auto at the end of November 1905, French sceptics reacted condescendingly and even aggressively. The Wrights were called bluffeurs. Ernest Archdeacon – lawyer, balloonist, glider pilot and co-founder in 1898 of the Aéro-Club de France – was particularly disdainful, even though he flew a Wright Brothers No. 3 glider. ‘The French’, he opined, ‘would make the first public demonstration of powered flight.’ On 10 February 1906, an editorial in the Paris edition of the New York Herald, a newspaper evidently detached from events in the United States, sneered, ‘The Wrights have flown or they have not flown. They possess a machine or they do not possess one. They are in fact either fliers or liars. It is difficult to fly. It’s easy to say, “We have flown.”’

Within three years, newspapers would be caught up in the story of powered flight and speed, to the extent that their sponsorship inaugurated early air races and long-distance contests – which, of course, promised sensational and popular news. Rather like Thomas declaring to his fellow apostles that he would only believe in the risen Christ when he had seen his master’s wounds and thrust his hand into his pierced side, the sceptical and proud French needed direct evidence of the Wright brothers’ ability to fly.

Wilbur arrived in France in summer 1908 with a machine that, in his expert hands, flew figures of eight above the crowds thronging the Hunaudières horse racing circuit near Le Mans. Apologies in print followed immediately afterwards – notably from Ernest Archdeacon, a doubting Thomas for whom the Wrights were now nothing less than the high priests of powered flight.

Over the following year, Wilbur made some 200 demonstration flights in France and continued his conversion of unbelievers in Italy, where he trained a new breed of military pilot. On 31 December 1908, Wright won the first International Michelin Cup, as it was soon known, taking home a bronze trophy by the French sculptor Paul Roussel depicting what looks like a Wright machine climbing into the sky, a winged spirit of victory perched on its prow bearing aloft a laurel wreath. Wright also pocketed 20,000 French francs. To win, he had to make the longest flight possible before sunset, over a 2.2-kilometre course at Le Mans laid out in the form of an isosceles triangle. Taking off at 2 p.m. he completed 56 circuits and, having landed and won, took off again to fly a further 1.5 kilometres to set a new world distance record of 124.7 kilometres (77.5 miles).

The revved-up fascination with powered flight was such that France hosted the world’s first air race, the Prix de Lagatinerie. This was held on 23 May 1909, the opening day of Port-Aviation near Juvisy-sur-Orge, 20 kilometres south of Paris. The world’s first purpose-built airfield boasted sheltered public grandstands, paid for by Baron Charles de Lagatinerie, that proved their worth when 50,000 or so people turned up on this blazingly hot day to witness the race. Charles and Bernard de Lagatinerie put up a prize of 5,000 francs for the pilot who covered 10 laps of a 1.2-kilometre course in the shortest time. Stops would be allowed. In the event of all aircraft being unable to complete the course, the prize would be awarded to the pilot who flew the longest distance.

There were nine entries, although only four showed up: three French pilots flying French Voisins, and the Austrian engineer Alfred de Pischof with a Pischof et Koechlin machine featuring three pairs of wings in tandem. This intriguing aeroplane, which Pischof designed and built with the Alsatian engineer Paul Koechlin, needed – or so it was thought – no more than a horizontally opposed 20-hp two-cylinder air-cooled engine by Dutheil and Chalmers to compete with the Voisins and their 50-hp water-cooled eight-litre Antoinette V8s.

In the event, an increasingly fractious crowd had to wait until a quarter to six in the evening before the go-ahead was given for the start of the contest. By this time, inadequately stocked bars and food stalls had run dry and empty. Even before the flying had begun, people hoping to get back to Paris on the crowded roads and trains before it got dark started to drift away from the grandstands. The day, they made clear, had been a fiasco.

Pischof was first to start. His machine refused to lift from the ground. Next came Léon Delagrange in an early-model Voisin. As he made his run, the elevator controls snapped. Delagrange ground to a halt. Up went Henri Rougier in a new Voisin. It was all looking good until a pair of spectators who had been sunning themselves in the long grass suddenly stood up as Rougier approached close to the ground. Their appearance caused him to swerve and crash. No one was hurt, but his Voisin was out of the race.

An impromptu entry by Louis Lejeune in a 12-hp Pischof et Koechlin–powered biplane of his own design followed. Lejeune scythed through the tall grass to cries of ‘la moissoneuse’ (‘the harvester’) from the crowd, his aeroplane resolutely refusing to take off. Now, Delagrange was allowed to try again in a Voisin borrowed from the airfield’s flying school. Climbing to an impressive 50 feet, he managed five laps at an average speed of 33.75 km/h (21 mph) before the engine overheated, encouraging him to land. Getting on for eight in the evening and with the weather turning, the fourth contestant, ‘F de Rue’, a pseudonym for Captain Ferdinand Ferber, chose to stay on the ground. Delagrange was declared the winner, although because he had failed to last the course, he was presented with half the prize money.

If the Port-Aviation event proved to be a bit of a joke in terms of organization, and a disappointment because there was so little flying in the course of a long day, it did show how keen the public was to come to a flying show. Many had never seen an aeroplane before. They were not there just for an entertaining day out, but also to bear witness to a new technology at work in a realm that, until now, had been exclusively that of insects, birds and gods. True, vultures in Africa might soar as high as 37,000 feet, butterflies close to 20,000 feet, locusts 15,000 feet and bats 10,000 feet; and yes, a peregrine falcon can dive at 220 mph and a dragonfly – with its ability to move its four wings independently of one another, and to rotate them forwards and backwards – can fly straight up, straight down, backwards, and can hover and turn in an instant at 30 mph. Yet humans had only just learned to power themselves into the air; and, until very recently, it had been said that this was impossible.

What was to prove truly remarkable in the following decades was the sheer pace of development in the speed, ability and reliability of aircraft. Many people alive in 1969, the year Concorde first flew and Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the Moon, remembered news of the Wright brothers and their first powered flight.

These early days of trial and error, sheer derring-do and earnest competition gave opportunities for men – and women, too – from a wide variety of backgrounds to take part in events and to fly machines that were often as dangerous as their pilots were inexperienced. Orville and Wilbur Wright, though, were safe and experienced pilots. It was typhoid fever that was to kill Wilbur in 1912 at the age of 45. He had stopped flying only the year before to concentrate on building up the Wright aircraft business. Orville last piloted an aircraft in 1914, giving up flying altogether four years later. He held the controls of an aircraft again in 1944, when a brand-new Lockheed Constellation airliner – piloted by Howard Hughes, TWA’s major shareholder, and the airline’s president Jack Frye – touched down at Wright Field on the return leg of a high-speed test flight from Burbank, California, to Washington, DC and back. Speaking from the co-pilot’s seat, Wright noted wryly that the wingspan of the 375-mph ‘Connie’ was greater than the distance of his first flight. He died the year after Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in level flight in a Bell X-1 rocket engine aircraft.

The pioneers of powered flight were excited first and foremost by the adventure of flight, and by the future possibilities it offered. Just how fast, how high and how far might an aeroplane fly? They wanted to find out, and were in a hurry to do so. Although science-fiction stories had depicted flying machines as potential instruments of death in future wars, such thoughts would have been very much at the back of the mind of young men like Léon Delagrange, Henry Farman and Gabriel Voisin.

Delagrange’s life was to be as intense and significant as it was brief. A sculptor trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, in March 1907 – at the age of 35 – he bought the first Voisin aeroplane. He did this even before it had proved capable of sustained and controlled flight in a circuit, which it did in January 1908 near Paris, with Farman (who had bought the second Voisin the previous October) in the pilot’s seat. With the help of Farman and Delagrange, Voisin – a contemporary of Delagrange’s at the École des Beaux-Arts and the creator of Europe’s first successful heavier-than-air aircraft – was on his way to becoming a major manufacturer of military aircraft during the First World War.

Having originally trained as an architect, Gabriel Voisin was to abandon aircraft production at the end of the First World War. He rued the production of Voisin bombers and the destruction they brought, by night, to towns and cities – and to enemy positions, too. Turning to cars, at which he excelled, Voisin was a man of peace again, yet one with an eye to the future. He sponsored the radical young Swiss-French architect known as Le Corbusier, including the sensational project Plan Voisin (1925), a proposal for a new high-rise quarter of Paris for 3 million people. Its construction would have spelled the erasure of the old 3rd and 4th arrondissements of the city that, sordid perhaps in the 1920s, have since been renovated and are treasured today.

‘I shall ask my readers’, wrote Le Corbusier in his description of the project,

to imagine they are walking in this new city, and have begun to acclimatise themselves to its untraditional advantages. You are under the shade of trees, vast lawns spread all round you. The air is clear and pure; there is hardly any noise. What, you cannot see where the buildings are? Look through the charmingly diapered arabesques of branches out into the sky towards those widely spaced crystal towers which soar higher than any pinnacle on earth. These translucent prisms that seem to float in the air without anchorage to the ground – flashing in summer sunshine, softly gleaming under grey winter skies, magically glittering at nightfall – are huge blocks of offices. Beneath each is an underground station. Since this City has three or four times the density of our existing cities, the distances to be traversed in it (as also the resultant fatigue) are three or four times less. For only 5–10 per cent of the surface area of its business centre is built over. That is why you find yourselves walking among spacious parks remote from the busy hum of the autostrada.

Le Corbusier’s drawings depict aircraft weaving their way above and across this sky-high, yet verdant and airy, Paris of the future. Two years earlier, in his iconoclastic polemic Vers une Architecture, Le Corbusier had shown photographs of aircraft – cars, too – juxtaposed with great buildings of the past. This was a new machine aesthetic positing new ways of building; new forms of architecture every bit as valid as those of the past. Aircraft were revolutionizing the way we saw our towns and cities, and even the world.

Le Corbusier took up this theme again in 1935 with his startling book, Aircraft. These machines were not just beautiful things liberating humanity from the mire of the earth; they allowed us to look down on the mess we had created in what Le Corbusier saw as the formlessness and squalor of cities. From this modern perspective, he opined, ‘Cities with their misery must be torn down. They must be largely destroyed and fresh cities built.’ All the while, Le Corbusier drove Voisin cars, and had his daring new white villas in and around Paris – designed for well-heeled avant-garde clients – photographed for publication with a Voisin in view.

Unintentionally, Le Corbusier appears to have been heralding a time when aircraft would rewrite the history of our cities – which, of course, is what happened when, in the Second World War, entire quarters of historic cities were destroyed, their places taken all too often by piecemeal and third-rate versions of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin.

Aviation had seemed a far more innocent preoccupation when, towards the end of 1907, Léon Delagrange was elected president of the Aéro-Club de France. The following summer, on a tour of Italy with his ash-framed Voisin aeroplane, he taught his friend Thérèse Peltier, a fellow sculptor, to fly. Her solo flight in Turin’s Military Square – 200 metres at an altitude of eight feet – made this Parisian artist the first woman pilot, though she had yet to learn how to make a turn. Peltier fully intended to pursue her new sideline career. Sportingly, Delagrange put up a prize of 1,000 francs that autumn for the first woman aviator to pilot an aeroplane for one kilometre. Peltier began training.

In January 1910, she abandoned both the contest and flying altogether. Early that month, Delagrange was killed at Croix d’Hins, Bordeaux. Newly fitted with a 50-hp seven-cylinder Gnome rotary engine, generating twice the power of its original Anzani engine, Delagrange’s Blériot XI – one of three machines he had bought in 1909 to form a display team – dived vertically into the ground from between 60 and 70 feet. A headline in the New York Press on 5 January trumpeted, ‘Delagrange’s skull crushed by fall of monoplane flying in a gusty wind’. The story underneath, one of many carried in newspapers worldwide, told of how Delagrange was mangled under the wreckage of his machine:

He had been flying in a wind that had been gusty which frequently blew at the rate of 20 miles an hour. In spite of this disadvantage, Delagrange continued and had circled the aerodrome three times when suddenly as he was turning at high speed against the wind the left wing of the monoplane broke and the other wing collapsed. The machine toppled and plunged to the ground. Delagrange was caught under the weight of the motor, which crushed his skull. Delagrange’s flight was merely preliminary to the attempt, which he was to make in the afternoon, to break Henry Farman’s record. The aviator did not have time to disengage himself from his seat.

From that inauspicious start at Port-Aviation in May 1909, Delagrange had become world-famous. He reached the zenith of his fleeting flying career less than three months before his death – not in France, however, but at Doncaster Racecourse, Yorkshire. The event, though, was organized by a Frenchman: Frantz Reichel, sports editor of Le Figaro.

A dynamic industrial town, Doncaster was famous for both the graceful high-speed locomotives – built at its Great Northern Railway works – that had taken part in the legendary Railway Races to the North of 1888 and 1895, and for its horse races, including the St Leger Stakes first run in 1776.

This being Doncaster, prizes included the Great Northern Railway Cup and the Doncaster Tradesmen Cup. Aside from Delagrange, high-profile competitors in the nine-day event included Samuel Cody, an American and former Wild West showman who was the first man to fly a powered aircraft in Britain. Cody’s mount was the Cody Flyer, which he had built the previous year as British Army Aeroplane No. 1 at the Royal Balloon Factory, Farnborough, in the hope of winning a military contract. It was not to be. In February 1909, the Aerial Navigation Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence recommended that all government funding for heavier-than-air machines should stop. Airships yes, aeroplanes no. Their development, should it be thought necessary, was best left to the private sector.

This being England, the opening day of the Doncaster event was a write-off. Down came the rain. Winds were strong enough to provoke the collapse of Captain Walter Windham’s Windham No. 3 biplane. Despite the appalling weather, the 50,000-strong crowd was in high spirits. The pilots, meanwhile, learned to wrap up in much warmer clothes than they were used to wearing when flying in France. Collars and ties were still largely de rigueur, although some competitors adopted polo necks, but heavy overcoats and flying suits were the order of the day. Flying in the Yorkshire wind and rain proved to be a chilling and trying experience.

The next day, when 20,000 additional spectators were there in the afternoon – factory workers for the most part, on their half-day off with pay packets in their pockets – Delagrange stole the show. In the morning he flew to the rescue of Cody, who was thrown from his machine after hitting soft sand while trying to avoid a course-marker pylon. In the early afternoon, Delagrange won the Doncaster Town Cup with a five-lap flight of 5.75 miles in a fraction less than 11 minutes and 26 seconds. He also wowed the crowd by starting his Blériot single-handedly, leaping into the cockpit and taking off within 40 feet seconds later.

Sunday spelled church, chapel and rest. Monday was wet and windy again, with pilots compelled to land because the rain whipped their faces. Their heads were protected not by helmets but by cloth caps or woolly hats. Newly repaired, Captain Windham’s plane collapsed again. For the 50,000-strong crowd, this would have been the live, full-colour version of the grainy, fast-motion black-and-white film we watched over and again as schoolchildren, showing one venerable aeroplane after another shaking itself apart as it attempted to fly. The Doncaster crowd must have laughed at the self-destructing Windham biplane, just as we did at the improbable Edwardian aircraft that seemed guaranteed to do pretty much anything other than take off and fly.

Captain Windham was, in fact, a serious figure in early British aviation. He flew the first passenger flight in Asia – India, December 1910 – and, among his many other achievements involving automobiles and aeroplanes, in 1911 he launched the world’s first official airmail service with a 13-minute flight from the polo field at Allahabad to Naini station on the Calcutta to Bombay railway. The aeroplane, carrying 6,500 letters including one to King George V, was a Sommer machine, designed in France and built under licence by Humber in England. The French pilot, 23-year-old Henri Pequet, who had trained with Gabriel Voisin, had travelled to India by ship with a team and six aircraft from the Humber Motor Company to demonstrate the aeroplanes, at Captain Windham’s behest, at the United Provinces Industrial and Agricultural Exhibition in Allahabad. Here, as at Doncaster, Anglo-French collaboration was on adventurous and gentlemanly display.

There were at least two more notable events at Doncaster. On Wednesday, 20 October, Roger Sommer flew his Farman at night under the light of the Moon. The following Tuesday, the last day of the Yorkshire meet, Delagrange claimed an unofficial world speed record of 49.9 mph. Perhaps he would have managed that tantalizing last 0.1 mph, but after his third lap he was simply too cold to fly any further, let alone faster.

Despite the weather, the event was considered to have been a success by its organizers, by most of those who took part, and by many of the 170,000 people who had made their way to the Doncaster Racecourse to watch these newfangled aeroplanes fly. Unfortunately, internal politics left the story with a sour ending. Because the meeting had been held independently and without approval from the Aero Club of Great Britain (renamed the Royal Aero Club in 1910), which had organized its own simultaneous event at Blackpool, Delagrange and three other French pilots were banned from taking part in any contests held under FAI rules (founded in 1905, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale remains the governing body for air sports) for the rest of the year. Powered flight was not quite six years old, yet international regulations were already closing in, if not exactly clipping its wings.

Because it had attracted the cream of Europe’s racing pilots – French and British alike – the Doncaster meet trumped both the Aero Club’s Blackpool event and the Grande Quinzaine de Paris meet held at Port-Aviation. The latter was a hugely ambitious event stretched out over a fortnight. To make up for the fiasco of the first Port-Aviation event, the Parisian organizers enlarged the grandstands, provided parking areas and amply supplied the restaurants, as well as establishing a post and telegraph office to relay news. As the crowd was expected to be enormous, the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans (PO) announced special trains from Paris running every four minutes to Savigny-sur-Orge, the nearest railway station to the airfield. With the French president, Armand Fallières, due to visit on 14 October, gendarmes on horseback with the 27th Dragoons and the 31st Infantry Regiment were there to maintain order.

Forty-three aircraft were entered, although just six pilots completed a lap of the course and much of the flying was by greenhorns and so decidedly patchy. On Monday, 18 October, Guy Blanck, a novice pilot who bought a Blériot for the event even before he had learned to fly, crashed into one of the grandstands without any attempt to cut his engine as he swerved towards it. Standing by the fence, a woman named Madame Féraud was, as the illustrated sports magazine La Vie au Grand Air reported, ‘literally stripped by the propeller and had her left thigh and calf cut to the bone’. When Mme Féraud sued Blanck and the event’s organizers for 100,000 francs, her attempt backfired. The following June, a Parisian court decreed that as there were no rules for safety at airfields and that aviation was a dangerous activity, Blanck and his fellow defendants were not guilty of culpable negligence. Mme Féraud was ordered to pay the legal costs of the case.

The show’s star pilot, although he was eager to get away as soon as possible to Blackpool to take part in the Aero Club of Great Britain event, was Hubert Latham. Wealthy, daring and studiously insouciant, Latham had set a European nonstop flight record – one hour and seven minutes – with an Antoinette IV monoplane in May. One of the very best of early flying machines, the Antoinette proved sufficiently stable in the air for Latham to take both hands off the ‘steering wheel’ as he opened a silver cigarette case, lit up and smoked through his ivory holder. This may well have been the first intentional hands-free flight.

Like many – but by no means all – early aviators, Latham was a young man of independent means. His mother’s family were French bankers; his father’s English merchant venturers who had settled in Le Havre in the 1820s. Educated, for a spell, at Balliol College, Oxford, in 1905 the multilingual Hubert went on to fly a balloon across the Channel by night with his cousin Jacques Faure, competed in power boat races with an Antoinette motor yacht at that year’s Monaco Regatta, and led an expedition to Abyssinia the following year on behalf of the French National History Museum, to carry out surveys for the French Colonial Office. For this confident pioneer pilot, flying was, perhaps, little more than une part de gâteau.

In July 1909, Latham had attempted to cross the English Channel, both times ditching in the sea when his engine faltered – becoming, by default perhaps, the first pilot to land successfully on water. When asked on returning to Calais, by Harry Harper of the Daily Mail, if he was discouraged by his failure, Latham replied, ‘Not in the very least… A little accident to a motor, what is that? Accidents happen to bicycles, to horses, even to bath-chairs… We have a machine that can go on land, in the air, and in the water. It runs. It flies. It swims. It is a triumph!’

In August, Latham set a world altitude record of 155 metres (509 feet), flying an Antoinette IV at Reims. October’s Port-Aviation event, however, was not to be his finest hour. On Sunday, 10 October, the roads were jammed as an estimated 300,000 people attempted to travel down from Paris to Juvisysur-Orge. Latham felt forced to walk the last few miles. When he got to the airfield, the brand-new Antoinette VII he was posted to fly was unready. Three days later, strong winds and a misfiring engine prompted Latham to make an emergency landing, damaging his machine as he touched down on one wheel and buckling a wing. Back in the air again the following day and with President Fallières watching, Latham was forced to land prematurely again, after just half a lap.

Several more minor accidents interrupted the show. Nevertheless, despite a paucity of actual flying, as well as strong winds, crowded roads, a total failure on the part of the PO to run sufficient and adequate trains to anything like a realistic timetable, and a wildly overambitious programme, it was looked on as a popular event, if not a critical success.

The crowning glory of the meeting was something wholly unexpected. The gist of it is happily and urgently conveyed in a cable sent to the New York Times by the paper’s reporter on the ground:

OVER EIFFEL TOWER IN WRIGHT BIPLANE; Count de Lambert Flies from Juvisy to Paris, 15 Miles, and Back Again. WRIGHT WITNESSES FEAT Calls It the Finest Flight Yet – Lambert Says He Reached a Height of 1,300 Feet.

Charles de Lambert took off from Port-Aviation at 4.37 p.m. on Monday, 18 October, in his Wright machine. Wilbur Wright’s first French student-pilot, Count de Lambert was a confident flyer who had confided his audacious plan that day to just two of his friends. At Juvisy there was concern that de Lambert had vanished. Had he crashed? Far from it. The count had flown on to Paris, where he circled the Eiffel Tower and, it seems, climbed 300 feet above it, before heading back to Port-Aviation where he landed to thunderous applause at 5.25 p.m.

But while the public was thrilled, aviation experts were unsure how to respond. Orville Wright considered de Lambert’s exploit to be a dangerous stunt. The British weekly The Aero commented ‘like the Channel flight, it will be done again and again, and unless stopped by legislation, someone will be killed at it, but de Lambert is and remains forever the first man to do it. Therefore, all honour and glory to his performance, though he deserves permanent disqualification from all future competitions for having done it.’

The ‘Channel flight’ had caught the public’s imagination that summer. In October 1908, the Daily Mail announced a prize of £500 (at least £50,000 in 2020 money) for the pilot of the first powered flight across the English Channel before the end of the year. The French press said it was impossible, while Punch offered £10,000 for the first flight to Mars.

The British newspaper was surely asking too much of aircraft makers when it gave them two months to meet the challenge, but when the prize money was doubled for 1909, the race was on. For Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the Daily Mail, aviation was the most exciting phenomenon of the era. It promised to sell not just thousands or even hundreds of thousands, but millions of newspapers.

Founded by Northcliffe, then Alfred Harmsworth, in 1896, the defiantly populist Daily Mail saw its circulation rise to over a million within six years. By the time the Wright brothers made their epochal flight in December 1903, it was the world’s biggest-selling newspaper. Flight offered the Mail’s readers the kind of thrills and spills that would be superseded a century on by shopping, house prices and celebrity culture. And because by their very nature aeroplanes and air competitions were quick – ‘here today, gone this afternoon’ events, skimming through the public consciousness – they were a perfect fit for the fast-paced and youthful newspaper.

Lord Northcliffe let his editor, Thomas Marlowe, know exactly what he thought of the Daily Mail’s readers: ‘No good printing long articles. People won’t read them. They can’t fix their attention for more than a short time. Unless there is some piece of news that grips them strongly. Then they will devour the same stuff over and over again.’

Get them hooked on flight. Sponsor headline-fodder competitions. Print racy articles. Repeat in ever more exciting ways. Sweep up readers. Please advertisers. Make a fortune.

Louis Blériot, the French aircraft maker and pilot who claimed the prize on 25 July 1909, became an instant celebrity when – after a hair-raising flight from Sangatte near Calais lasting 36½ minutes, made without a compass in strong wind and deteriorating weather – he arrived at Dover Castle. Charles Fontaine of Le Matin was the first to meet him, much to the chagrin of the Daily Mail’s correspondent who, assuming Blériot would land elsewhere, had to dash by car to reach Northfall Meadow by the castle. Blériot had not been to Dover before and had been unsure where to land. Fontaine had selected a favourable spot and waved a large Tricolour to mark it as his fellow Frenchman came into view.

The news spread very quickly indeed, not least because the Marconi Company had established a cross-Channel radio link with stations at Cap Blanc-Nez in Sangatte, and on the roof of Dover’s Lord Warden Hotel. For Blériot, already a successful engineer and businessman – he had patented the first practical automobile headlamps, selling them from a Paris showroom – came fame followed by considerable wealth. By the end of the year, he had taken orders for a hundred aeroplanes, establishing himself as a major manufacturer. Buyers were inevitably impressed with the Blériot XI monoplane’s ability to cross a body of particularly demanding water from one country to another. And they were equally attracted to the arrangement of Blériot’s aircraft. These were monoplanes that, starting with the Blériot VIII of 1908, featured hand-operated joysticks and foot-operated rudder controls. This meant that they were easier and more natural to handle in the air than rival machines. The Blériot XI was also fitted with a strong and aerodynamic laminated-walnut propeller made by Lucien Chauvière, together with an equally sophisticated and reliable three-cylinder, 25-hp, three-litre engine by Alessandro Anzani, an Italian engineer settled in France.

The following month, in August 1909, Blériot took part in the Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne. Held in Reims, this was the world’s first international aviation meet. A grand and lavish event sponsored by champagne makers, featuring a 600-seat restaurant, a temporary railway station, 38 entries (23 of which flew) and a galaxy of cash prizes, the Grande Semaine received half a million visitors – among them David Lloyd George, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Lloyd George was an early champion of powered flight. Eight years on from Reims, and by now wartime prime minister, he celebrated what he saw as the noble role played by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Its aircraft were helping to end slaughter in the trenches. ‘The heavens are their battlefield’, the lyrical Welsh politician proclaimed. ‘They are the cavalry of the clouds. High above the squalor and the mud.’ In 1918, Lloyd George was responsible for the formation of a Royal Air Force (RAF) independent of the British Army and Royal Navy. His first President of the Air Council, the RAF’s governing body, was Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere – younger brother of Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, and co-founder of the Daily Mail.

Although Blériot won the Prix du Tour de Piste at Reims for the fastest single lap in his Type XII monoplane, flying at 76.95 km/h (47.8 mph), the celebrated pilot crashed on the last day, his machine bursting into flames. Blériot walked away from the accident, as did most early pilots from theirs, because his and most other early aircraft were light, and the speed and the height at which they flew were low. The French pilot would have been more concerned at coming second in a new, Americansponsored, contest the day before.

This was the first Gordon Bennett Trophy, an eponymous prize donated by the newspaper tycoon. It was the event that aviators, aircraft makers, bookmakers, organizers and the crowd were to take most notice of at the time. James Gordon Bennett Jr was an adventurous New Yorker whose father had made him editor of the sensationalist New York Herald in 1866. It was Gordon Bennett who financed Henry Morton Stanley’s presumptive and successful search for Dr Livingstone in Africa, and an ill-fated American expedition by ship to the North Pole. As the crew of the unfortunate USS Jeannette starved to death in and around the Bering Strait, circulation of the New York Herald soared.

Ever restless, Bennett, a Civil War Union Navy veteran, had competed in the first transatlantic yacht race in 1866, and won. His scandalous and racy behaviour in polite New York society – triggering the well-known British phrase ‘Gordon Bennett’ (another way of saying ‘gor’blimey’ or ‘bloody hell’) – caused Bennett’s move to Paris, where he launched the forerunner of the International Herald Tribune. Back in the States, his enthusiasm for polo, tennis, ballooning and automobiles encouraged him to announce a plethora of Gordon Bennett Cups in different disciplines. By 1909, and resident in Paris again, he became caught up in the newfangled craze for flying. His new trophy was, however, different from those to date. Entry would be by national teams rather than individuals. It set the tone and pace of aviation competitions for several years to come.

For the first contest, Louis Blériot, flying one of his own aircraft, had teamed up with Eugène Lefebvre, flying a French-built Wright Model A, and Hubert Latham in an Antoinette VII. George Cockburn, piloting a French Farman III, represented Great Britain. Glenn Curtiss was the one and only American pilot, his mount an aeroplane of his own design, the Curtiss No. 2, fitted with a 63-hp water-cooled V8 engine. Teams from Italy and Austria failed to materialize. The rules of the competition meant that the next contest would be flown in the winning team’s country, and the trophy would go permanently to the team that won the contest three times in succession.

Glenn Curtiss won the first Gordon Bennett Trophy contest at an average speed of 75.3 km/h (46.8 mph). He was named ‘Champion Air Racer of the World’. Blériot came second, only seconds behind the American whose ‘Reims Racer’ was a more manoeuvrable machine than the Blériot XII. Latham came in third and Lefebvre fourth. Cockburn was unplaced: on his first lap he flew into a haystack. After the event, Curtiss took off on a tour of Italy where, aside from winning prizes, he took Gabriele d’Annunzio for a brief spin in the air. Wilbur Wright had flown with the acclaimed poet the previous year. These fearless Americans and their aeroplanes were to have a powerful and lasting effect on D’Annunzio’s psyche.

Signing up for the Italian Air Force in the First World War, and by this time in his early fifties, D’Annunzio proved to be a daring military pilot. In August 1918, commanding 87th Squadron ‘La Serenissima’, he led 11 fast and serenely competent Ansaldo SVA biplanes on a return flight of more than 1,100 kilometres (700 miles) from Due Carrare, near Venice, to Vienna, dropping tens of thousands of green, white and red propaganda leaflets on the enemy city. Written by D’Annunzio, these warnings to the citizens of Vienna were in the form of orotund and provocative prose:

On this August morning, while the fourth year of your desperate convulsion comes to an end and luminously begins the year of our full power, suddenly there appears the three-colour wing as an indication of the destiny that is turning…

On the wind of victory that rises from freedom’s rivers, we didn’t come except for the joy of the daring, we didn’t come except to prove what we could venture and do whenever we want, in an hour of our choice.

As no one had translated the maestro’s lines into German, these may well have been ineffectual. Not so the leaflets dropped together with D’Annunzio’s and written by Ugo Ojetti, the respected journalist and wartime Royal Commissioner for Propaganda on the Enemy. This text was translated into German. In English, it reads:

VIENNESE!

Learn to know the Italians.

We are flying over Vienna; we could drop tons of bombs. All we are dropping on you is a greeting of three colours: the three colours of liberty…

VIENNESE!

You are famous for being intelligent. But why have you put on the Prussian uniform? By now, you see, the whole world has turned against you.

You want to continue the war? Continue it; it’s your suicide. What do you hope for? The decisive victory promised to you by the Prussian generals? Their decisive victory is like the bread of Ukraine: You die waiting for it.

D’Annunzio was to become an inspiration for Benito Mussolini and his Italian Fascist movement, for whom high-speed powered flight and the urgent pulse of new technology were as important to Italy’s twentieth-century renaissance as the revival of Roman architecture and city-making. Back in 1909–10, however, daring young pilots would not have known how the often awkward and dangerous aircraft they flew would shape political movements and war over the next 10 momentous years.

When Glenn Curtiss took part in the first US air meet, held at Dominguez Field, Los Angeles, in January 1910 – where he raised the world airspeed record to 55 mph – one of its main sponsors, Henry Huntington, the railroad and streetcar magnate, looked on unaware that within a few short decades the trains of the long-distance US railroads his family had built would be trounced by airliners capable of crossing the continent in a matter of hours rather than days.

Although hazardous and often frustrating for competitors, early air meets could be high-spirited events. On 4 November 1909, John Moore-Brabazon, the first English pilot to fly a powered aircraft in England, took a piglet dubbed Icarus the Second into the air with him to prove that pigs could fly. The following summer, Moore-Brabazon’s wife persuaded him to give up flying after his close friend Charles Rolls, of Rolls-Royce fame, was killed when the tailplane of his Wright machine broke off during an aerial display at Hengistbury Airfield, near Bournemouth.

Moore-Brabazon was to fly again, however, as a decorated pilot during the First World War. Appointed Minister of Aircraft Production by Winston Churchill in 1941, he resigned the following year after publicly expressing his hope that Germany and Russia would destroy one another. He went on to chair the Brabazon Committee focused on the development of the postwar British aircraft industry, and was closely involved in the development of the giant Bristol Brabazon airliner. In later life, he was president of the Royal Aero Club.

In the days of Edwardian flight, Moore-Brabazon had been one of those dashing and seemingly carefree young men whose exploits were to be recreated in Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines; Or, How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 Hours 11 Minutes, a 1965 film set in 1910. Directed by Ken Annakin, who had worked with the RAF Film Unit during the Second World War, it tells the story of a £10,000 prize offered by the fictional Daily Post, and starred a cornucopia of reliable British actors and comics, among them Sarah Miles, Terry-Thomas, James Fox, Robert Morley, Eric Sykes, Benny Hill, Tony Hancock, Flora Robson, Fred Emney, John Le Mesurier, Willie Rushton and Cicely Courtneidge. In 1910, Courtneidge had played lead role in The Arcadians, a hugely popular musical comedy, at London’s Shaftesbury Theatre. Doubtless some of the real-life young flyers would have gone to see her in that entertaining piece.