9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

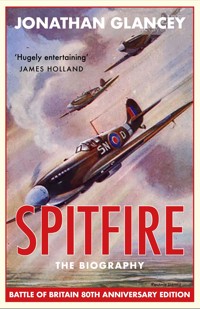

Updated edition to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain. It is difficult to overestimate the excitement that accompanied the birth of the Spitfire. An aircraft imbued with balletic grace and extraordinary versatility, it was powered by a piston engine and a propeller, yet came tantalisingly close to breaking the sound barrier. First flown in 1936, the Spitfire soon came to symbolize Britain's defiance of Nazi Germany in the summer of 1940. Spitfire: The Biography is a celebration of a great British invention, of the men and women who flew it and supported its development, and of the industry that manufactured both the aircraft and the Rolls-Royce engines that powered it. It is also about the ways in which the sight, sound and fury of this lithe and legendary fighter continue to stir the public imagination worldwide more than eighty years on.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

SPITFIRE

Jonathan Glancey is well known as the former architecture and design correspondent of the Guardian and Independent newspapers. A frequent broadcaster, his books include Wings Over Water, The Journey Matters, Concorde, Harrier, Giants of Steam, Spitfire: The Biography, Nagaland: A Journey to India’s Forgotten Frontier, Tornado: 21st Century Steam, The Story of Architecture and London: Bread and Circuses.

‘Hugely entertaining, Spitfire is told with the passion and style that this most iconic of aircraft deserves.’ James Holland

‘A drama that cannot help take wing. The elements still excite the imagination and raise the heart.’ Tom Fort, Sunday Telegraph

‘Eclectic and entertaining’ Patrick Bishop, Literary Review

‘Stylishly written and entertainingly told, Spitfire is a real treasure-trove of fascinating anecdote... A wonderful book.’ Rowland White

‘Elegant and meticulously researched... an authoritative and comprehensive tribute to a unique aircraft.’ Adrian Swire, Spectator

‘Superbly readable’ Giles Whittell, The Times

By the same author

Wings Over WaterThe Journey MattersConcordeHarrierGiants of SteamSpitfire: The BiographyNagaland: A Journey to India’s Forgotten FrontierTornado: 21st Century SteamThe Story of ArchitectureLost Buildings

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This updated paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright ©Jonathan Glancey 2006, 2020

The moral right of Jonathan Glancey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Pbk ISBN: 978-1-83895-069-9

E-book ISBN: 978-0-85789-510-3

All technical drawings by Mark Rolfe © Mark Rolfe Technical Art

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Altlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

I can hardly better the dedication Alfred Price made in his excellent Spitfire: A Complete Fighting History ‘to the men and women who transposed the Spitfire – a mere fabrication of aluminium alloy, steel, rubber, Perspex and a few other things – into the centrepiece of an epic without parallel in the history of aviation’.

And in loving memory of my father.

CONTENTS

List of illustrations

Introduction

I Of Monoplanes and Men

II The Thin Blue Line

III Survival of the Fittest

IV The Long Goodbye

V First among Equals

VI The Spitfire Spirit

Epilogue

Postscript to the 2020 edition: Ad Astra

Technical Specifications

Select bibliography

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Pages

2. A restored Spitfire Mk I. Copyright 2006, Herbie Knott/Rex Features.

7. The author’s mother and father. Author’s collection.

21. R. J. Mitchell. Getty Images (2680725).

25. A Supermarine S 6B seaplane. The Flight Collection (11567).

44. The Spitfire prototype, K5054. The Flight Collection (12902s).

52. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding escorts King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. Imperial War Museum (CH1458).

66. Gun camera footage taken from a Spitfire Mk I. Imperial War Museum (CH1830).

69. Robert Stanford Tuck. Imperial War Museum (CH1681).

74. A Spitfire Mk IA of 19 Squadron. Imperial War Museum (CH1458).

82. Air Transport Auxiliary pilot Diana Barnato-Walker. By permission of Diana Barnato-Walker.

87. Joan Lisle.

90. A trainee pilot takes off in a Spitfire Mk II. Imperial War Museum (CH6452).

93. Flight Sergeant James Hyde. Imperial War Museum (CH11978).

105.Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park. Imperial War Museum (CM3513).

121. Spitfire Mk VIIIs of 136 Squadron. Imperial War Museum (CF682).

130. The black Spitfire Mk IX. Getty Images (52693336).

135. A Seafire Mk 47 of 800 Squadron.

145. A Spitfire PR XIX.

148. The first Griffon-engined Spitfire Mk XIVE. Imperial War Museum (EMOS1348).

153. Adolf Galland. Imperial War Museum (HU4128).

169. A line-up of Italian Macchi MC 202s.

173. A restored Japanese Mitsubishi A6M3 Zero. Brian Lockett.

181. A Russian Lavochkin La-7.

198. A poster for The First of the Few, released in the US as Spitfire. RKO Radio Pictures Inc/Photofest.

205. Advertisement for the ‘Dan Dare’ cartoon in The Eagle. Colin Frewin Associates.

210. An Airfix 1/48 Spitfire Mk VB. Author’s collection.

213. A PR Mk XI Spitfire. Imperial War Museum (EMOS1325).

218. A restored Spitfire Mk IX. Copyright 2006, Herbie Knott/Rex Features.

INTRODUCTION

‘IT’S the sort of bloody silly name they would give it.’ R. J. Mitchell, inventor of the Spitfire, the most famous, best-loved and most beautiful of all fighter aircraft, was not exactly impressed by the tricksy appellation some cove flying a desk in Whitehall is said to have come up with for his prototype Supermarine Type 300 monoplane. The aircraft answering to Air Ministry specification F.37/34 had, in fact, been named by Sir Robert McClean, chairman of Vickers, the company that had bought the Supermarine Aviation Works, after his young daughter Anna, a right little ‘spitfire’. As for Merlin, the name given to the magnificent 1,000-hp Rolls-Royce V12 aero-engine that powered the Spitfire, this had been a wonderfully apt choice by Rolls-Royce itself. The Merlin proved to be the stuff of mechanical wizardry and, as the loudly beating heart of the stunning little fighter aircraft that soared into British skies against Hitler’s Luftwaffe in 1940, it was a significant part of the spell, and more than a flash of the sorcery, that led to the Nazis’ Götterdämmerung in 1945.

Rolls-Royce had actually named what was to become its most famous aero-engine not after the Arthurian wizard but after the falcon the Americans know, rather prosaically, as the pigeon hawk, and the British, more poetically, as the merlin. Rolls-Royce had a policy of naming its engines after birds of prey – the Eagle, Kestrel, Peregrine, Griffon and Vulture were all installed with varying degrees of success in RAF aircraft. The Merlin, though, was a perfect match from the very start for Mitchell’s promising little fighter. The avian merlin is a raptor with thin, pointed wings that allow it to dive at startling speed. The Spitfire’s famously thin wing enabled it too to dive at very great speeds, so much so that in 1943 one of Mitchell’s sensational machines was not so very far from breaking the sound barrier. Not that a piston-engined aircraft ever has achieved this; it took the custom-designed and rocket-powered Bell X-l, ‘Glamorous Glennis’, to do the job in October 1947 with Captain Charles ‘Chuck’ Yeager at the controls. During the Second World War, Yeager had flown the North American P-51D Mustang, a superb American fighter powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin, built under licence by Packard in Detroit. It was also the stuff of aeroindustrial sorcery.

A restored Spitfire Mk I rolls above the Seven Sisters Cliffs, Friston, West Sussex, in 1988.

The fastest falcon of all, the peregrine, can reach a speed of up to around 200 mph in a headlong dive in pursuit of its prey. The Victorian Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins evoked the flight of a smaller but no less mercurial raptor, the kestrel, in an exhilarating, tonguetripping poem, ‘The Windhover’:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, kingdom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing, As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

When I first read those words, dedicated by the poet to ‘Christ Our Lord’, I was a schoolboy at what I thought of as a Catholic Stalag Luft. I was fascinated by birds and in love with aircraft and the idea of flight, and I thought of Hopkins’s falcon as a Spitfire scything through the air, ‘off forth on swing as a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend’. It was as if Hopkins had actually seen a Spitfire, another kind of saviour, in flight – although if he had, he would surely have described the sound of the Merlin engine that accompanies the flight of this most dangerously exquisite mechanical bird of prey. The Merlin’s voice is all thunder and lightning, a deep, pulsing roar overlain with the throaty whistle of its supercharger.

‘Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! spout, rain!’ Even in this line from Shakespeare’s King Lear (Act 3, scene 2) that I happened to alight upon at much the same time as I flew on mind’s wings with Hopkins’s falcon, I could hear the basso profundo thrum of a Merlin and the blazing sight and chattering sound of Browning .303 machine-guns, or the pom-pom thud of Hispano 20-mm cannon, raining revenge from the wings of a fighter that really did spit fire.

Of course, for any English schoolboy of my generation who could assemble 1/72 scale Airfix Spitfires – a squadron of them, in fact, lovingly painted and detailed, complete with oil leaks from their glossy black Merlins – and do so without spreading strands of Britfix 77 glue and telltale fingerprints across their Lilliputian windscreens, there was another poem, that those who loved aircraft, yet pretended not to care a fig for literature, knew by heart:

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long delirious, burning blue,

I’ve topped the windswept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or even eagle flew –

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

In this poem, ‘High Flight’, the flight of the Spitfire is rhapsodically evoked. It was written by Pilot Officer John Gillespie Magee Jr, an American Spitfire pilot, born in Shanghai, who crossed the Canadian border illegally in 1941, while still a freshman at Yale, to serve with the Royal Canadian Air Force in England. ‘An aeroplane,’ he wrote home while undergoing basic training in Canada, ‘is not to us a weapon of war, but a flash of silver slanting the skies; the hum of a deep-voiced motor; a feeling of dizziness; it is speed and ecstasy.’ Of his flying, his instructor noted, ‘Patches of brilliance; tendency to over-confidence.’

Magee flew a Spitfire Mk V with the RCAF’s 412 Squadron from Dibgy, Lincolnshire, from 30 June 1941. In early September, he wrote to his parents, after a high-altitude test flight, ‘I am enclosing a verse I wrote the other day. It started at 30,000 feet, and was finished soon after I landed. I thought it might interest you.’ On the back of the letter was ‘High Flight’, written on 3 September, exactly two years after Great Britain had declared war on Germany. On 11 December 1941, three days after the United States entered the war, Magee was killed in a flying accident close to RAF Tangmere. A farmer saw his Spitfire drop from the sky, and watched as Magee bailed out. His parachute failed to open. His grave is in the quiet churchyard of Holy Cross, Scopwick, Lincolnshire. In icily precise lettering, a white military tombstone reminds us that he was just nineteen years old.

‘The Windhover’, Lear raving, Magee’s ‘High Flight’: these loops and rolls of words all fuse and fly together in the delirious blue of the imagination to shape a portrait of the Spitfire, a winged minion of death chevying on air-built thoroughfares, one of the finest aircraft yet designed. A man of matter-of-fact sensibilities, Mitchell himself would have turned on his heel and walked out of the drawing shop rather than listen to any of this florid, literary hyperbole; yet the Spitfire was a brilliant name, at once lyrical and charismatic. Deadly accurate, too.

Mitchell preferred the name ‘Shrew’, which proves that perhaps he really did have no ear for poetry. Supermarine Shrew sounds plain wrong, even though in Elizabethan England shrill and shrewish women were often called ‘spitfires’. The shrew itself is a truly voracious predator – but short-lived. The pygmy shrew, the fiercest of the breed, burns itself up in an orgy of hunting to stay alive; it rarely soldiers on beyond fifteen months before giving up its tiny ghost. Many Spitfires, along with their young and inexperienced pilots, were destroyed within a day or two of going into battle. The record went to a Spitfire Mk I, X4110, which was delivered to 602 Squadron, West Hampnett, near Chichester, on 18 August 1940: within two hours it was being flown in anger by Flight Lieutenant J. Dunlop-Urie and jumped by Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Dunlop-Urie survived a crash landing; X4110 was written off. Very few Spitfires were to survive all six years of the Second World War. Those that did included the very first delivered to an RAF squadron in 1938. Yet even when short-lived, a Spitfire was always more than a shrew.

I cannot remember a time when Spitfires did not play some part in my life. My Uncle Jack, a Wellington man – bomber, not school – was shot down and killed over Klagenfurt, Austria, in 1944, flying on a mission with 70 Squadron from Foggia on the Adriatic coast of Italy. My father had clearly loved his younger brother and so, I suppose, this was in part why he, like so many others who had friends and relatives killed in the Second World War, was not particularly keen to talk about combat. My father’s blue RAF jacket hung in the furthest recesses of a capacious bedroom wardrobe. His medals, a little tarnished, lay unceremoniously in a pewter cigarette box. In my parents’ bedroom, there was a lovely wedding portrait of them, taken in 1940 – my father in uniform, my mother with an RAF wing brooch pinning the top of her blouse. There were battered, green-painted steel models of Spitfires and Hurricanes, and of enemy fighters and bombers, used for identification and training purposes, in a dark and cobwebbed shoe-cupboard. The only tales my father liked to tell of those days were of his times towards the end of the war in the jungles of Burma, and in the Naga Hills, of the writhing body of a poisonous snake he mistook for a showerhose when he had suds rather than the sun in his eyes, or of how beautiful the Buddhist temples of Rangoon were. I liked the silk pilot’s maps he would have carried in a pocket, and the guide to surviving a crash in the jungle. The advice on what to do if he had met a tiger was nicely to the point: pray.

The author’s mother and father, then an officer cadet, at the time of their engagement.

There were dog-eared boxes on a shelf at the top of a cupboard stuffed with wonderfully crisp black-and-white reconnaissance photographs, taken at little more than tree height from the noses of Beaufighters and the bellies of Spitfires. Many featured temples, not because these were potential RAF targets, but because they acted as turning points for aircraft and, I like to think, simply because they were beautiful to look at, as if someone, centuries ago, had decided to turn the sun into architecture. So, although as a boy I walked stiff-legged behind Douglas Bader, who found this funny, although I knew my Stalags and my Spitfires inside out – even the firing order of the Merlin’s twelve cylinders, starting with 1A, followed by 6B and ending with 2B after 5A – although I had mastered every last detail of all the fighter aircraft that flew in the Second World War, although I had devoured Guy Gibson’s Enemy Coast Ahead, Pierre Clostermann’s The Big Show, P. R. Reid’s Escape from Colditz, The Cockleshell Heroes by C. E. Lucas Phillips, and countless other wartime epics, I was to remain frustrated, all too aware that fighting talk among the adults I knew was taboo. Combat could only be exercised in black tar playgrounds when we played British vs Germans and Spitfires vs Messerschmitts, coming in to land, after furious, dakka-dakka machine-gun fire, only when the school bell clanged and we were grounded by arithmetic, spelling, rulers across the backs of legs and religious instruction.

My Uncle Reg, a major blown up in Libya on service with the Eighth Army and with a hole in his head you could place your index finger in, told me that only those who ‘fought from the cookhouse’ banged on about ‘action’ – and killing. In RAF terminology, he meant those who ‘flew desks’. None of this matters much; what does matter is that, although I adored Spitfires from primary school age, I never really thought of what it must have been like to have killed in one, even though I must have drawn hundreds of Spitfires blazing away at Stukas and Messerschmitts on the pages of my school exercise books; nor what it would have been like to have had someone trying to kill me.

The mortal reality of aerial combat remained the stuff of boys’ comics read on floors, among a tangle of dogs, head held in cupped hands. There was Paddy Payne, Warrior of the Skies, in the Lion. I pored over his adventures even before I could read. The scripts, I learned much later on, were by a chap called Mark Ross; they were chock-full of classic wartime comic-book phrases such as ‘Achtung! Spitfeur!’, ‘Teufel!’, ‘For you, Herr Payne, the war is over’, ‘Cop a load of this, Fritz’ and ‘Ach! The fortunes of war’, along with a hamperful of ‘goshes’ and ‘crikeys’ amid guttural, sausage-eating exclamations of ‘Gott im Himmel!’ and ‘Donner und Blitzen!’. As for the drawings, by Joe Colquhoun, who had also drawn the original ‘Roy of the Rovers’ strips in the Tiger, these were both accurate and exciting. They included, as best I can remember, various marks of Spitfires, including Fleet Air Arm Seafires and, rather surprisingly, Spitfire floatplanes, only a handful of which were ever built. They even had Squadron Leader Payne threatened by such Nazi exotica as the Bachem Ba 349 Natter (Viper), a tiny rocket-powered interceptor that was meant, in theory, to have shot up into formations of Allied bombers at a truly astonishing rate of climb. It let loose its twenty-four rockets, and then rammed one of the enemy aircraft in a final gesture of defiance as the pilot ejected his way to safety in what little remained of Nazi Germany in the spring of 1945.

Paddy Payne, of course, gave the Natter short shrift in what, I suppose, must have been a late-model, Griffon-engined Spitfire. Payne’s Second World War was to continue for thirteen years in the pages of the Lion – more than twice as long as the real war and far longer than my interest in reading his adventures. In that time, he must have shot down pretty much the entire Luftwaffe. No wonder the Germans of the liberal and democratic Bundesrepublik were upset; no wonder they said the British were still obsessed by the war.

As I grew up, so my love for the Spitfire evolved, just as the machine itself was to do between 1936 and 1947. As I spread my wings, so the Spitfire flew with me. When I first went to France as a schoolboy, now in love with architecture of every era, and under my own steam – in fact, on the last of the Chapelon Pacific locomotives running from Calais Maritime to Abbeville on the way to Paris – a Spitfire Mk IX flew overhead. The sight encouraged me to read again the memoirs of the French ace Pierre Clostermann (thirty-three kills claimed), this time, haltingly, in the original. Years later, when I travelled as a student to India, to Burma, the Naga Hills and beyond, I met men who had flown or serviced Spitfires. When I first went to see the extraordinary concrete architecture created by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, the new capital of East Punjab, I found a Spitfire Mk XVIII in retirement at the local Punjab Engineering College. Later still, I learned to fly and eventually progressed from Tiger Moths to the cockpit of a Spitfire Mk VIII. I cannot really add anything to the praise that has been heaped upon the Spitfire; it is truly an aircraft the pilot wears like a second skin. I have driven many fine sports cars of all periods, yet none comes remotely close to the precision of a Spitfire. It scythes through the air like the sharpest imaginable blade. It pulls on the heartstrings even as it concentrates the mind. It is a mechanical spirit of ecstasy, the very sensation of flight.

The Spitfire stays with me. What I have learned in recent years is sketched through the pages of this book. When I was a small boy, I thought that the Spitfire was flown exclusively by decent British chaps of my father’s generation and social set, men who drove wire-wheeled MGs with black labradors in the passenger seat, along with a few plucky Poles thrown in for good measure. Since then, I have learned that Spitfires were flown by both men and women, not just from across Britain, its Commonwealth, Empire and class spectrums, but by Czechs, Russians and Americans too. Indian Sikhs in turbans flew them. Black West Indians. A Navajo Indian. After the Second World War, rival Spitfires were flown in anger by Israelis, Syrians and Egyptians. French Spitfire pilots strafed guerrillas in French Indo-China; RAF Spitfire pilots did the same in Malaysia.

Spitfires flew under the flags of many nations: Australia, Belgium, Burma, Canada, the People’s Republic of China, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Egypt, France, Greece, Holland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the Soviet Union, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, the United States and Yugoslavia. Perhaps fittingly, the last time a Spitfire flew in military service was in England in 1963, when a Mk XIX, the fastest of all the Spitfire marks, was pitted in a mock dog-fight against a frontline RAF Lightning jet-fighter capable of Mach 2. It had seemed possible at the time that the Lightning might be sent to Indonesia, where it would fly against P-51D Mustangs. The RAF felt that its fighter pilots needed to know what it might be like if they came up against one of these still potent Second World War veterans. The Spitfire was the nearest thing the RAF had to a Mustang. It acquitted itself remarkably well.

I have talked to those involved with the Spitfire in one way or another over the course of four decades. I think I know enough about the aircraft themselves (although any corrections to this book, which cannot pretend to be definitive, are welcome), and yet there is always more to learn about the men and women who together wove the tale of this magnificent machine. This, in any case, is really their story, not mine. And, of course, the story of that remarkable fabrication of aluminium alloy, steel, Perspex and rubber.

CHAPTER I

OF MONOPLANES AND MEN

WAS the Spitfire a work of art? It is a perennially fascinating question, even if of little interest to military experts or historians, and its answer is inseparable from the neverending debate as to which was the better fighter, the Spitfire or the Messerschmitt Bf 109. The Bf 109, some would claim, was the superior wartime machine because it was easier, and so cheaper, to build than the Spitfire. A kit of parts that slotted and bolted together in precise, factory-like fashion, the German fighter was also simpler to service and maintain. It was, therefore, the more truly industrial machine – not so elegantly formed or finely crafted as the British Spitfire, but an instrument of death better suited, perhaps, to a machine-age war in which command of the air was essential to victory. In fact, the Spitfire’s unstated artistry counted against it.

As it was, both aircraft were developed and manufactured throughout the Second World War: altogether, some 31,000 Bf 109s were built and some 22,000 Spitfires. Both were highly successful, but in the end the RAF was on the winning side and so the argument was always going to be academic. In reality, there had not been much between the performance of these rival fighters, although development of the Bf 109 finally tailed off as the Allies squeezed into submission both Nazi Germany and what had been, until remarkably late in the conflict, its astonishingly productive war machine, driven by the architect-turned-armaments minister Albert Speer. As much as anything else, it was the quality of pilots that made the difference.

A Spitfire was a superb fighter, but even some of its best pilots, from a purely aeronautic point of view, were poor shots and so unable to make the most effective use of this finely honed weapon of war. The top-ranking Spitfire pilot measured in terms of number of kills made during the Second World War was Johnnie Johnson, who shot down thirty-eight enemy aircraft. The leading Luftwaffe aces, with most of their kills made through the gunsights of Bf 109s, were Erich Hartmann (352), Gerhard Barkhorn (301) and Gunther Rall (275). Despite this huge discrepancy between the scores of British and German aces, this did not reflect on the relative efficacy of their aircraft. Where RAF pilots were recalled for rest, training and fresh assignments, their Luftwaffe counterparts were expected to fly until they died, or the war was won. They also flew, especially in the first two years of the Russian campaign, against an inexperienced enemy yet to be equipped with either the commanders it needed or the right sort of aircraft. Flying against the RAF was a very different proposition, although even then German aces ruled the roost until well into the Battle of Britain.

Spitfire and Messerschmitt were certainly products of two very different industrial cultures. Where the Bf 109 was undoubtedly a practical, economical and workmanlike piece of design, the Spitfire emerged from a culture famous for producing lithe, good-looking and even sensual machinery. The Spitfire, then, was a thing of complex compound curves, of wings blended gracefully into a smoothly lined fuselage requiring a great deal of hand-finishing. In fact, the Spitfire was considered to be so difficult and expensive to build that the Air Ministry very nearly cancelled orders for it as late as May 1940. But the Spitfire flew as beautifully as its catwalk looks suggested it would. Its elegant elliptical wings – which meant that, in general, it could be mistaken for no other aircraft – may well have been expensive and tricky to make, yet their slim and effectively swept-back profile enabled the aircraft to turn tight circles and, as engines became ever more powerful, to dive and to fly still faster and to meet the ever-increasing demands of the war in the air.

Ultimately, the Spitfire proved capable of further development than the Bf 109, and it continued into production well into 1947. The very last Spitfire to be produced – the F 24 – weighed half as much again as the first machines, could climb twice as quickly, had a top speed 25 per cent higher and could pack a much greater punch with its four 20-mm cannon and, if required, rockets and 500-lb bombs. These end-of-line Spitfires are fine-looking machines, although they are clearly tougher and less overtly crafted or, dare I say it, artistic than either Mitchell’s prototype or the Battle of Britain’s legendary Mk Is.

Mitchell, of course, would have dismissed any reference to art or artistry in the design of the Spitfire as stuff and nonsense. He saw himself as an entirely practical fellow, and the aesthetic of his fighter purely the product of the functional requirements, mathematics and aerodynamics that governed its form. Beverley Shenstone, the young Canadian aerodynamicist who worked closely with Mitchell on the design of the prototype, recalled: ‘I once remember discussing the wing shape with him, and he said, jokingly, “I don’t give a bugger whether it’s elliptical or not, so long as it covers the guns.’“

Did Mitchell protest too much? At school he had been good at art, while his younger brother Billy was very good indeed. Billy set up his own business designing patterns for Royal Crown Derby, Minton, Spode and other leading companies in the English ceramic industry centred on Stoke-on-Trent. Stoke had been one of the crucibles of the Industrial Revolution, and it was where art and industry were fused together for the first time to create what was known as industrial art and what we know as industrial, or product, design.

Reginald Joseph Mitchell was brought up in a world of art, artistry, machines and smoking chimneys. One of five children, he was born on 20 May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, near Stoke-on-Trent, in a house flanking what is now the busy A34 trunk road. The Reginald Mitchell Primary School is just down the road from Number 115. Reginald’s parents, Herbert Mitchell, a Yorkshireman, and Elizabeth Brain, were both successful and well-respected teachers. Herbert later set up a printing business and the family moved to 87 Chaplin Road, Normacott, a terraced house in a suburb of Longton. Today, the ground floor is home to Tony’s hairdressing salon.

Mitchell was already making model gliders from strips of wood and glued paper when the Wright Brothers made their first powered flight from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. He was gripped by the idea of flight and yet when he left Hanley High School he began an engineering apprenticeship with Kerr Stuart, a local firm of locomotive builders that had moved from Glasgow to Stoke-on-Trent in 1892. In some ways, Kerr Stuart seemed an odd choice for a young man with a flair for art as well as maths; the locomotives made by the company were prosaic machines built to standard designs and sold ‘off the shelf’, mostly to narrow-gauge railways around the world. Some, like the ‘Wren’ 0-4-0 saddle tank, were very small indeed, weighing less than Stephenson’s Rocket of 1829, and few Kerr Stuart locomotives would have been much, if at all, faster than that famous Regency flyer. Examples of the kind of Kerr Stuart locomotives Mitchell would have been familiar with can be seen working today on narrow-gauge railways including the Talyllyn in North Wales, the Great Whipsnade Railway at the Bedfordshire zoo, and the Sandstone Steam Railway in South Africa. Modest machines, they have nevertheless travelled as extensively as Spitfires, if rather more slowly.

If Mitchell had been apprenticed to Kerr Stuart just a few years earlier, his path would have crossed that of Tom Coleman, another highly practical engineer with excellent maths and an artistic bent, the latter something he, too, would vigorously deny all his life. It is to Coleman we owe the splendid ‘Princess Coronation’-class Pacifics of 1937, designed under the direction of William Stanier, Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London Midland and Scottish Railway. Stanier was away inspecting locomotives in India during the genesis of these magnificent machines, yet they were to prove the most powerful (3,333 ihp) and, at 114 mph, the second-fastest class of British steam locomotives on record. They combined a restrained beauty and nobility of line that was very much down to Coleman, who was also directly responsible for their heroic performance, economic working, reliability and popularity among crews, maintenance staff, railway management and travelling public alike. Like Mitchell, Coleman was an essentially shy and self-effacing chap, a team player in an enterprise he always saw as much bigger than himself.

I mention Coleman because he came from the same social and engineering culture as Mitchell. These were men who knew, as if by instinct, how to draw a beautiful line, but would have denied that their machines were works of art in any sense, not even accidentally. And yet both achieved feats of engineering design that were to stir hearts and imaginations. They are, too, a part of the same breed as those who went on to design such exquisitely beautiful machines as Concorde; official research on the development of a revolutionary supersonic airliner began just two years after the last, subsonic, piston-engined Spitfire retired from regular duties with the RAF in 1954, and indeed the Spitfire had played its part in some of the earliest research into supersonic flight.

Although it is easier to imagine the young Mitchell at work on the design of high-speed railway flyers rather than narrow-gauge plodders, the lightness of Kerr Stuart locomotives may well have appealed to him; in any case, his sights were set high above narrow-gauge rails and very firmly on aircraft, and flight. While working in the drawing office at Kerr Stuart, he pursued a higher education, studying engineering, mechanics and advanced mathematics at night school. At home, he used what spare time he had to work at his own lathe in an effort to master practical engineering skills.

Mitchell’s industry paid off. At the age of just twenty-two, he was taken on at the Supermarine Aviation Works. This had been founded on the site of a former coal wharf on the River Itchen at Woolston, Southampton, in 1913 by Noel Pemberton-Billing, a yacht dealer, and his friend Hubert Scott-Paine, to build seaplanes. Pemberton-Billing was a racy character. He lived on his three-masted schooner moored in the Itchen. Of the money he put up to found Supermarine, £500 had come from a wager; Pemberton-Billing had bet that he could gain his Royal Aero Club certificate, or flying licence, within twenty-four hours of first sitting at the controls of an aircraft. He won. In 1914, as a reserve officer in the Navy, he helped to organize a daring bombing raid by British naval aircraft on German Zeppelin sheds on the shore of Lake Constance. Pemberton-Billing was elected a Member of Parliament, and to avoid a clash of interests with his business affairs – something hard to imagine today – he handed Supermarine over to the equally restless Scott-Paine.

It was Scott-Paine who hired Mitchell, and Scott-Paine who was to get Supermarine involved in the famous Schneider Trophy air races. He moved on, in the mid-1920s, to form British Power Boats, where he was to design and build the highly successful Type 2 HSL air-sea rescue boats, first launched in 1937. ‘Flown’ by RAF crew, these 63-foot boats were powered by Napier Sea Lion aeroengines and had a top speed of thirty-six knots. They served with distinction throughout the Second World War and were used in the first British Commando raids against naval targets in Germanoccupied France. Spitfire pilots would have every reason to be grateful to Scott-Paine. In hiring Mitchell, he got them up into the air; by producing the Type 2 HSL, he brought them home safely when they fell from the sky, and into the drink.

Within three years of arriving in Southampton, and by now married to Florence Dayson, a headmistress from back home in Stoke, Mitchell, or ‘RJ’ as he was known at Supermarine, became the company’s Chief Engineer. Between 1920 and 1936 he designed twenty-four different machines ranging from light aircraft and fighters to huge flying boats and bombers. Not all of these went into production, but they show the range of his aerial ambition, and the depths of his skill as a designer. With this prodigious and prolific talent at the drawing board, Supermarine was to remain profitable throughout the great economic depression that was to sink so many businesses in the years following the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Mitchell’s genius as a designer and engineer was to think for himself, in his own time, while listening to everyone around him. He would not have fitted easily into the structure of a modern company where crushingly boring meetings, inane management jargon, market research, focus groups and corporate culture are all-important. He was, in any case, rather shy, with a bit of a stammer, and, perhaps as a result, notoriously blunt. He needed time by himself for thinking, walking, sailing, shooting or playing golf, or just sitting in a deckchair listening to birds sing in his garden. Although he was one of those men of whom obituaries say ‘he did not suffer fools gladly’, Mitchell – ‘Mitch’ to his test pilots – was respectful and loyal. He gave talented colleagues their head. He listened intently to what the most junior fitter had to say. And he said a most emphatic ‘No’ to Vickers Aviation (Vickers-Armstrong from 1938), the company that bought out Supermarine in 1928, when it tried to foist its own chief designer on his team. That designer was Barnes Wallis, who went on to shape the Vickers Wellington bomber, invent the bouncing bomb of Dambusters fame and, later, to pioneer the swing-wing technology that produced the distinctive supersonic F-111 bomber for the United States Air Force in 1967. That Mitchell could dismiss such obvious talent, and get away with it, says much about both the quiet force of his personality, and how highly he was regarded by the desk-jockeys of the mighty Vickers corporation.

R. J. Mitchell at a Schneider Cup dinner in Southampton in 1931.

Many of his more prosaic aircraft might surprise those who know Mitchell only for the Spitfire. The highly successful Supermarine Southampton and Stranraer flying boats were, for example, very much workaday machines. Rather ungainly-looking biplanes, they flew low, slowly and well, around the world. The Southampton, rather resembling a survivor drawn from the embers of the First World War, flew with the RAF from 1925 to 1936, while its successor, the only slightly sleeker Stranraer, performed with the RAF and RCAF throughout the Second World War. My great aunt Flo and her gun-toting mercenary partner Mervin, who had shot his, and her, way out of Japanese-occupied Singapore and who settled in Vancouver after the Second World War, recalled flying Queen Charlotte Airlines’ Stranraers along the coast of British Columbia.

These flying boats represent one very important aspect of Mitchell’s work: safety. He was one of the very few aircraft designers who learned to fly, and this showed in the way his aircraft handled both on the ground and in the sky. Fast and deadly though it was, a Spitfire was a very safe aircraft to fly – and easy too. Many Second World War pilots were to be grateful to Mitchell, not just for the Spitfire they chased the enemy with, but also for his tough little Supermarine Walrus amphibian, first flown in 1936; one of these would often be there to rescue them when they were forced to bail out over water or ditch into the sea. Walrus biplanes flew, with their top speed of just 145 mph at 4,750 feet, trouble-free throughout the Second World War. Even the Walrus, though, could be flown with surprising brio. Flight Lieutenant George Pickering, Supermarine’s test pilot, made a point of looping the loop in new Walruses floated out from the factory. He liked to start his loops from as low as 300 feet: Mitchell, with a little help from his pilots, was truly a wizard of flight.