Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

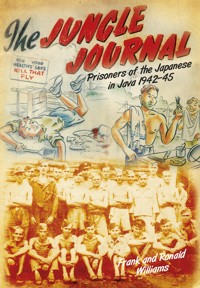

This is the story of a young Royal Artillery officer, Lieutenant Ronald Williams, who was held as a prisoner of war in the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies from 1942–45. It is a true account of the alternate horror and banality of daily life, and the humour that helped the men survive the beatings, deprivation and death of comrades. Told through the diary and papers of Williams and others, Jungle Journal includes many cartoons and poems produced by the prisoners, as well as extracts from the original Jungle Journal, a newspaper created by the men under the noses of their guards. Ronald Williams was the 'editor' of this potentially fatal 'publication'. Jungle Journal describes the survival of hope even in desperate straits, and is a testament to those men whose courage and fortitude were tested to the limit under the tropical sun.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 412

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Java, a most beautiful and enchanting island, witnessed unspeakable horrors against both man and beast during the Japanese military occupation, 1942–45.’

Ron Williams, 1946

Dedication

This small volume is dedicated to those men and women, from all services and walks of life, and of all nationalities, who maintained their pride with great courage, while captives of the Japanese in the Far East, from 1941–1945.1

Please note that sections in italics, throughout the following text, are comments by Frank Williams.

Note

1 For the Japanese the dates are 2602-05, according to their calendar.

This book is dedicated to my mother, Margaret, now in her mid-nineties, who had to endure four years of early marriage (November 1941 to October 1945) without my father, Ronald. For nearly sixteen months, she did not know if he was dead or alive in the Far East. She was only fifty years of age when he died and never remarried. Margaret joined the Japanese Labour Camps Survivors’ Association to help keep the plight of civilians and service members who had been in the Far East under Japanese rule in the media and political spotlight. Eventually, the British Government paid some reparations for the hardships suffered. Unfortunately, the Japanese remain in denial of war atrocities committed by their military, against many nationalities, from 1930 to 1945.

All royalties earned from the sale of this book are shared between Help for Heroes and the Java FEPOW Club 42.

Acknowledgements

The publishers and I would like to thank Richard Reardon-Smith, Peter Williams, Karen Williams, Margaret Williams, Ann and Sandra Williams, Barrie and Jan Williams, the late Brynmor Davies, Richard, Roger and Liz Thomas especially; the Imperial War Museum (IWM), particularly Roderick Suddaby (FEPOW expert); The Java 42 Club with considerable help from Lesley Clarke, Margaret Martin and Bill Marshall; Kathleen Booth (daughter of Gunner Harry Hamer) for manuscript corrections and her invaluable assistance with personal details through her encyclopaedic knowledge of the 77th HAA Regiment; Mrs Adèle Barclay for permission to reproduce illustrations from The Jungle Journal; the National Archive, Kew; the Artillery Association, Woolwich; Western Mail newspapers; COFEPOW Association; De Pen Gun newspaper; and Raymonde ‘Nikki’ Sullivan.

My father also wished to thank the following for their help when he was writing his original manuscript:

I wish to extend my sincere appreciation to Charles Holdsworth, who collaborated with me in the production of magazines in prison camps and supplied the artistic illustrations for this book. I would also like to thank Jean Teerink for the information embodied in the article ‘Life in a Women’s Internment Camp on Java’. To the men, British, Commonwealth, Dutch and American, who supplied drawings and inspiration – you will always be in my thoughts, particularly those who did not make it back to freedom.

The Netherlands newspaper De Pen Gun provided material for the article ‘When a Dark Night Descended on the Dutch East Indies’. For the chapter on the history of Java, I am indebted to a book entitled Ons Zonneland by A.J. Krafft, M.J. Overweel and M.J. Offringa, published by J.B. Wolters ‘Uitgevers-Maatschappij’, of Groningen and Batavia. This was a constant companion to me during my time in captivity which helped me to learn Dutch and discover the intriguing history of the Dutch East Indies. I found useful references from the Encyclopaedia Britannica and for the short historical sketch I consulted The Lights of Singapore by Roland Bradell, published by Metheun and Co. Ltd.

I express my sincere gratitude to all.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Major General Morgan Llewellyn

Introduction

Part I: ‘Under the Poached Egg’

1 Diary of the 77th’s ‘Hell on Paradise Island’

2 My Time in Japanese POW Camps around West Java

3 Records of Violations against POWs in 1945 and POW deaths 1942–45

4 Authentic Anecdotes and Insights gathered by Ronald Williams from POW Camps on Java

5 Verses in Captivity, 1942–45

6 End of the Nightmare and the Journey Home

Part II: Appendices

1 Volunteering for Military Service

2 A Dark Night Descends over the Dutch East Indies

3 Camp Journals Produced in Captivity, 1942-45

The Jungle Journal Part 1: Editorials and Captivity

The Jungle Journal Part 2: The Camp Life of the POW

The Jungle Journal Part 3: Humour and Recreation

4 Alleged Japanese Atrocities Committed on Java and on the Java Sea in 1942

5 One Came Back Home

6 Christmas Day and the Monkey (1943)

7 The Nippon Times

8 Life in a Women’s Internment Camp on Java

9 The Island of Java

10 Correspondence and POW Mail

11 History of the 77th Welsh HAA Regiment, Royal Artillery (TA)

Epilogue

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Foreword by Major General Morgan Llewellyn

On 25 October 1945, Ronald Williams wrote that he was ‘seriously considering publishing a book about his experiences in captivity’. Now, after more than half a century, his son Frank has brought this book to fruition. Frank has done this with great skill, weaving his father’s own writings into a narrative that deserves to be widely read. Not only does Ronald write about a theatre of the Second World War that has, undeservedly, been neglected by historians, but he does so with great perception, sensitivity, and often with a hint of humour which could only survive in a man who possessed an honourable and courageous nature. This book tells his story from the moment he volunteered for service in the Royal Artillery Regiment of the Territorial Army until he was eventually released from military service in 1946.

The book takes the reader on the long journey to the Far East, where Ronald gives his own graphic account of the fierce attempt to defend the island of Java from the Japanese – against the odds – and gives us a unique insight into the humiliation of surrender and the horrors, depravation and cruelty of life in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. However, there are lighter moments with Ronald’s involvement, as editor, in the production of a camp magazine, The Jungle Journal. His story ends with the defeat of the Japanese and his return home at the end of the war.

For me the story is particularly poignant as my father was chairman of a company that grew rubber and coffee in Java and Sumatra. Ten years after the end of the war I, too, went to serve in the Far East and was to return on one of the troopships, the Dunera, which formed part of the convoy in which Ronald sailed from the Clyde. For a short time, at the end of the Malayan emergency, I lived in the Selarang Barracks where, Ronald recounts, prisoners of war were forced to sign oaths of good behaviour by the Japanese.

All young people at school who are studying the Second World War as part of the National Curriculum should read this book. It tells of an important theatre of war and a human experience that should never be forgotten.

There is an immense amount to be learned from it. Aspects of this forgotten war will, no doubt, seem strange to young people today. However, some of Ronald Williams’ experiences of action and fortitude will, no doubt, have been echoed in recent years, albeit in widely differing circumstances, by those fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. This shows how the human spirit can transcend even the harshest and most demoralising of conditions and rise to acts of compassion and creativity.

Ronald Williams is self-effacing about the quality of his own poetry that is included in this book. I am no literary critic when it comes to poetry, but I find that his verses move me because they are an uninhibited expression of the ever-changing emotions of prison camp life. They show that even in degrading camp conditions there survives nobility which demands admiration. His poetry reflects the intensity of his friendships, his patriotism and his faith; qualities which are much needed in today’s world.

His son, Frank, is to be congratulated on bringing his father’s legacy into the public domain and the book is commended to all who share Ronald Williams’ values.

Major General the Revd Morgan Llewellyn, CB, OBE, DL,

General Officer Commanding Wales, 1987–1990

Introduction

It is over forty years since my father died, aged 58 years. He died from a heart attack, in part because of the effects of smoking (a habit he picked up during the war years), but it was also due to the long-term debility he suffered through privation, disease and malnutrition from over three and a half years’ incarceration in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps in Java.

Premature death rates amongst ex-FEPOWs (Far East Prisoners of War) were four times greater than other Second World War Allied POWs, those held by the Germans and Italians, and war veterans.2

My father documents in his papers, passed on to me by my mother on the 60th anniversary of VJ (Victory against the Japanese) Day, that it would have been his intention to publish them on his retirement. He spoke very little of his own immediate prisoner of war experiences to family and friends, a common trait amongst ex-FEPOWs.

I remember, when I was young, a close friend and ex-POW colleague of my father, ‘Mossie’ Simon, would visit and they would engage in long conversation about old times behind closed doors. My father also kept in close contact with four fellow Australian POWs, part of ‘Sparrow’ Force captured on Timor and transported to Java: George Gunn, ‘Scotchie’ Morrison, Don Junor and Ray Vincent. They remained close friends until my father’s premature death.

After my father’s death, my mother wrote on a number of occasions to the Australians, seeking insight into what had happened on Java, but they said, ‘Don’t ask!’ The Australians did state that Ronald was one of the most popular of the Allied junior officers because he placed other prisoners’ welfare above his own. It seems probable that he would have been beaten up by camp guards for sticking up for his men. This would have been a humiliating experience for a former schoolboy boxing champion and a man who always believed in fair play but who could not retaliate on pain of death.

Fellow POW Arthur Holt (ex-RAF) wrote in a citation for my father:

I have known in days of privation, and suffering, the strength of his [Lieutenant Williams’] steadying influence. All those ‘other ranks’ who, like myself, had the good fortune to know Mr Williams, and those were numerous, will testify to his unfailing efforts to make their lot a more comfortable one, to his remarkable sense of humour when it was most needed, and to his utter unselfishness which commended him to all with whom he came into contact. A man’s true character quickly came to the fore in those dark days.

My father mentioned to me that fellow internee Laurens van der Post, the well-known South African novelist, put the matter of dealing with the Japanese (Jap or Nip for short) and Koreans very succinctly: ‘It is one of the hardest things in prison life: the strain caused by being continually in the power of people who are only half sane and live in a twilight of reason and humanity.’3

Ronald said that he did not suffer from the ‘Rip Van Winkle’ effect of waking up from a dream, which many ex-POWs were supposed to have experienced; his experiences remained vivid, although he chose to talk little about Java until a short time before he died. It has recently come to light that returning FEPOWs were told by RAPWI (Recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees) officials that discussing their POW experiences with family and friends was inadvisable and there was general discouragement by the authorities to mention anything regarding the ‘Japanese experience’. The reason given was that such discussions would be detrimental to the mental healing process. In my view, however, this was a deliberate attempt to avoid embarrassing the post-war Japanese Government and to suppress the apportioning of blame for the calamitous Allied Far East military campaign during 1941-42. Ronald felt that FEPOWs were an embarrassment to the Allied authorities due to the abject failure of the 1942 campaign in the Far East.

Ronald felt fortunate to have remained on Java throughout his captivity as many of his friends who were drafted to other South East Asian islands and the Japanese mainland had died on their transport ships (usually sunk by Allied planes and submarines because of the Japanese refusal to put any recognition marks on their boats indicating the presence of POWs and wounded). Others had to undertake inhuman work in places like Siam (now Thailand), Burma and Japan. Many died from this experience.

He survived a number of serious illnesses during captivity. He told my mother that during times of ill-health his men would drag him out on a work detail, prop him up in the shade with a hoe, and do his work for him (Allied junior officers were responsible for work details and increasingly forced to undertake manual work). They also gave him extra food. Without this help, he said, he would have perished either ‘naturally’ or through the thrust of a camp guard’s bayonet.

On 7 December 1941, Ronald had left Gourock Docks, Glasgow, aboard the troop ship Empress of Australia, the very same day Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese. He was expecting to be fighting the Germans in the Middle East, but ended up fighting the perpetrators of this notorious act.

After capture, he was not heard from again until news came through from New Zealand to Burnie, Tasmania and finally Pretoria, South Africa, in June 1943 that his name, family address and a simple message had been broadcast on Tokyo Radio on 23 April 1943.

He did not receive any mail from my mother until May 1944 (although he had received two notes from his father, Frank Sr, in 1943); then followed a deluge of mail, some three years old. Prisoner mail went on a circuitous route via Japan and was viewed by various Japanese censors. This process alone could take nine months to a year!

Following the Japanese surrender in 1945, the POWs were not ‘out of the woods’. There was a risk that the POWs would be massacred by their former guards, or by the hostile Indonesian nationalists. This did happen in some camps but, fortunately, not in my father’s camp, where some of the Japanese guards remained armed to protect their former charges.

There had been instructions from the Japanese High Command in Tokyo to eliminate all evidence of Allied Prisoners of War. The plan had been to poison the civilian prisoners and bayonet the POWs, then burn their bodies or bury them in mass graves. This was known as the ‘Final Disposition’ and did occur on some of the islands. This strategy was designed to allow Japanese soldiers to return immediately to Japan to repel any Allied invasion and remove all evidence of the countless atrocities that had been committed in the Far East. The atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima subverted these directives.

Ronald wrote a great deal of poetry whilst in captivity and two Dutch books, En eeuwig zingen de Bosshen, by Dr Annie Posthumus, with a distinct Javanese cover design, and Ons Zonneland, were my father’s constant companions during captivity and contained much of his written work, drawings and pressed flowers. He also organised a camp journal, The Jungle Journal – although production was often interrupted by camp guards confiscating pens and paper. Some of this material, which has recently come to light in the Imperial War Museum, is included in this book, which is, partly, based on a combination of handwritten material and a typed manuscript my father was intending to publish. The remainder I have compiled from archival material, newspaper articles, family letters, other personal accounts, and archive material from the Imperial War Museum that covers the period from Ronald joining the Royal Artillery in 1939 to his homecoming in 1945.

My father returned home in late October 1945. My mother’s description was of a barely recognisable, emaciated man with severely cropped hair, yellowish skin, sunken eyes and dreadful teeth (due to severe gum disease, Ronald lost his teeth in his early forties although he had good healthy teeth and gums prior to the Java POW experience). He weighed only a little over seven stones, just over half his normal body weight. Considering he had been well fed since release, his physical state was still appalling. Many released FEPOWs believed that their stomachs had shrunk, due to years of starvation, and they could not rapidly build up their body weight. My mother said that his appearance turned heads in public for several months and he never recovered the self-confidence and self-esteem he had prior to going to Java. For a number of years after the war he had nightmares and he became anxious if left on his own for more than a few minutes.

This book is a unique record of a forgotten part of the war, which helps paint a picture of what Japanese prison camps in west Java were like. No official Allied military records survived the Java campaign and personal records are sparse, although Lieutenant Colonel (Lt Col) H.R. Humphries, Commander of the 77th Artillery Regiment, did manage to keep some records of events on Java on six pieces of rice paper, which he kept in a wooden box (a transcript of which can be found in the National Archives at Kew). The Japanese burnt all archives of POW camps and often silenced, permanently, any witnesses to their atrocities.

Unlike Ronald, who said he would be happy to shake a Japanese person’s hand, many men who survived being Japanese POWs maintained a deep hatred of their former oppressors. However, Ronald would not purchase post-war Japanese merchandise as he felt this would be his best form of protest. He was deeply disappointed that many bad Japanese and Koreans were never brought to war crimes trials. He would have been dismayed that the Japanese royal family and government ministers continued to pay homage at the Yasukuni Shinto shrine, Tokyo, which subsequently contained the remains of many ‘Class A’ Japanese war criminals.

It has been alleged that, in 1949, the US Government deliberately curtailed Japanese war crimes investigations, as the trail was leading directly to Emperor Hirohito.4 Thus, many cases of Japanese brutality, cannibalism, prisoner experimentation for bio-warfare, and mass sexual slavery have remained uninvestigated and unchallenged to this day. There has been no hunt for Japanese war criminals, which is in stark contrast to the clamour for finding Nazi war criminals by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre.

Frank Williams

Notes

2Australian Medical Journal, 1989

3A Bar of Shadow, 1954

4 In 1971 Hirohito was made a Knight of the Garter by the British Government, much to the consternation and protest of many ex-FEPOWs. I am relieved that my father was no longer alive to witness this extraordinary event.

Part I: ‘Under the Poached Egg’

By Ronald Williams (Unwelcome ‘Guest’ of the Imperial Japanese Army on Java, 1942–1945)

The Japanese flag was often referred to, for obvious reasons, as a ‘poached egg’ and the POWs were the ‘toast’ for over three and a half years! Illustration by Charles Holdsworth

[This was to be the original title of Ron Williams’ book which he was planning to write on return from Java. He contacted many old friends after the war to help fund its publication, but this proved ultimately too difficult. His later ambition was to produce the book on his retirement but this was not to be, due to his premature death.]

1: Diary of the 77th’s ‘Hell on Paradise Island’

Beginnings

On 5 December 1941, I was on a train to Gourock Docks, on the Clyde, with my regiment and later that day, as my diary notes, ‘took a ship’s tender to a converted ocean-going liner, the Empress of Australia’. This was to be our troopship for the next couple of months. We were part of the Convoy WS (William Sail) 14, which included the Warwick Castle (a converted Union ship), the Empress of Asia (later sunk in Singapore harbour), and Dunera, all troopships, and Pretoria and Troilus (later a stalwart in Malta convoys) carrying heavy equipment. [The 77th Artillery Regiment was 1,007 strong on departure.]

We had been joined by Light Anti-Aircraft Regiments the 21st, 48th, and 79th and accompanied by a Royal Naval escort. After we were under way, news was coming through that the Japanese had attacked the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and also bombed Singapore and Hong Kong. We had no idea at this time that the Japanese would be our enemy in less than two months, as we were expecting to be joining General (Gen.) Auchinleck’s forces in the Middle East. [Sixteen warships were sunk or severely damaged in the bombing of Pearl Harbor, including four battleships, 188 aircraft were destroyed and 2,400 Americans were killed and 1,178 injured.]

Royal Artillery cap badge. Illustration by Sgt J.D. Bligh of 239 Bty.

Empress of Australia was a very comfortable troop ship. [Empress of Australia carried 239 and 241 Battery (Bty) and Warwick Castle carried 240 Battery. The Regimental HQ was split between the two ships.] We had good meals and plenty of time and space for relaxation, but then, several days out to sea, we came under attack from German bombers. There were no direct hits but transporter Pretoria, while avoiding the bombing, began shifting cargo and started listing. We subsequently learned that a great deal of damage to vehicles and heavy equipment had occurred on board the Pretoria – ‘bad luck for us, but lucky German bombers!’ In fact, damage to some of our equipment did cause us significant problems later, on Java. [Lt Col Humphries reported that he had complained about the handling and loading of fragile equipment at Gourock, by the Royal Engineers (RE). Heavy equipment had been placed on fragile equipment and colour markings for each gun unit had not been adhered to, either by the RE or ship’s tender operators.]

Vigilance was required out at sea as further bombing was anticipated. We underwent weapons training and operated guns on rotation. The ships practised anti-submarine manoeuvres from time to time and lookouts were posted for submarines and surface magnetic mines. I relaxed by writing, mainly poems and short stories, and by getting my men to provide cartoons and drawings.

Our original ‘mystery’ destination, we were informed, would be Basra, in the Persian Gulf, where we were to protect the docks and railhead. We had a brief stop in Freetown, Sierra Leone, to refuel and take on provisions (a very hot Christmas Day!), before a good break in Cape Town, South Africa between New Year’s Eve and 4 January 1942.

I had to keep an eye on some of our boys who were being offered a ‘king’s ransom’ to work in the gold mines. Many of the 77th were from mining areas, particularly the Rhondda valley. Spirits were very high at the time and we were just looking forward to giving ‘Jerry’ payback for their imperialistic menace in the Middle East and most of Europe.

On setting sail from South Africa things began to change – there were strong rumours that our convoy would be heading into the Indian Ocean as the Japanese had advanced through Malaya and the Philippines at an alarming rate, with the battleship Prince of Wales and consort vessel Repulse having been sunk (on 10 December 1941). The destination was to be somewhere in British South East Asia – this venture would be an interesting experience since we were all geared up for desert, rather than tropical, warfare!

We learned that our old chums of 242 Bty were to head for Basra, but the rest of us were to go to the Far East. The convoy split east of the Cape – we were likely to be heading for the ‘Fortress City’, Singapore. This was in fact the destination for part of 241 Bty. We learned subsequently that we were on our way to the Dutch East Indies ‘Spice Islands’ – Japanese here we come!

At that time, although Pearl Harbor and the rapid advance in the Philippines and Malaya were recognised, we were led to believe that the Japanese would run out of steam owing to lack of equipment, air support and the presence of a great many conscripted troops. Our morale remained high and we anticipated stopping the Japanese advance. Unfortunately, the Allies seriously underestimated the fighting ability of the enlisted Japanese soldier.

On 3 February we entered the Sunda Strait, west of Java and south of Sumatra, accompanied by HMS Exeter and the Dutch cruiser Java. We docked at Rotterdam wharf, Tandjong Priok, Batavia (later called Djakarta), west Java, part of the Dutch East Indies. A Japanese reconnaissance plane had already spotted our convoy and shortly afterwards we were subjected to a period of moderately heavy bombing from Japanese planes coming from Celebes and southern Borneo. The ship’s anti-aircraft guns opened up on the bombers and, as we were concerned for the men and equipment, delayed disembarkation until the bombing ceased. [Humphries’ records indicate that 239 Bty disembarked at 1900 hrs on 3 February under Major (Maj.) Leslie Gibson and 240 and 241 Btys disembarked at 0600 hrs on the 4 February and entrained to Soerabaja .]

Early next day, on 4 February, the men and some equipment moved off the ships. I was partly responsible for helping organise gun battery emplacements around the port of Batavia. 239 Bty was to stay in Batavia while the rest of the regiment was to travel east to the main Dutch naval base at Soerabaja (later called Surabaya). [Humphries records that air raid alarms were frequent at the port, which disrupted the moving of equipment off the ships. It took seven days to completely unload and organise stores and equipment.]

It was apparent that Soerabaja was suffering heavy bombing, with the eastern Allied airfields at Madion and Malang subject to intense daily bombing. Unfortunately, some of our equipment was either incomplete or damaged and in need of repair, particularly the gun springs, some of the range finders and gun transporters. This was the inevitable consequence of the convoy splitting in the Indian Ocean and the bombing.

We stayed at the Dutch KNIL (Koninklijk Nederlansch Indish Leger), Royal Dutch East Indies Army Cornelius barracks, Batavia. Brigadier (Brig.) Hervey Sitwell, an artilleryman, arrived to be our C-in-C. Arrangements were made for the transfer of 240 and 241 Btys and the Regimental HQ, including our own commanding officer, the monocled and gatered Lt Col H.R. Humphries (affectionately known as ‘HRH’ or ‘Col Bob’), with his faithful shooting-stick, to Soerabaja on a fast troop train. Problems were encountered with the heavy gun transfer by train, owing to overhead obstructions.

5 February

The bulk of the officers and NCOs went on the train to Soerabaja, while the guns and heavy equipment went by road, a good 500 miles on not very good quality roads. Some units of other regiments have been transferred by ship to Sumatra, Bali and Timor to protect ports and airfields. Vehicles heading for Soerabaja required green netting to conceal the desert camouflage!

6 February

In the early hours of this morning (at about 0245 hrs) a major disaster struck. The train carrying the 77th officers and NCOs was in a head-on smash with a stationary train carrying munitions and fuel on a single line at Lahwang, near Malang. It was probably an accident due to brake failure, though some suspect sabotage as the stationary train’s driver was missing and the area was known to be rife with Japanese collaborators. There are also likely to be Japanese agents on the island, as the Japanese had free access to Java up to the declaration of war.

It is reported that thirty men were killed (five officers and a large number of NCOs) and up to one hundred injured (forty-three seriously), including my best friend, Medical Officer Captain (Capt.) John W. Goronwy, (RAMC), who suffered a broken jaw and arm, and also Flight Liuetenant (Flt Lt) Dawson, another medic. A Section of 241 Bty suffered the highest number of casualties. Killed were Capt. H.M. MacMillan, and Lieutenants (Lt) J.K. Ainsley, W.L. Black, J.A. Boxall, J.H. Stoodley, and D.P. Cox (who died later from his wounds). Stoodley, Black, Boxall and Ainsley were all good friends and likely to have been together at the time of the accident. Gunner (Gnr) Harry Hamer commented about the rail crash:

Amongst the debris lying around,

T’was death and mutilation we found.

The number of victims was very large;

T’was a question of accident or sabotage?

Through all sorts of storms in life I’ve been,

And I have witnessed its seamier lights,

But never again in all my life,

Do I want to witness such ghastly sights.

[There are no official records recording deaths and injuries from this accident although Humphries records that ten coaches were badly damaged, with the first four completely wrecked. Twenty-one died at the scene: five officers and sixteen ORs (other ranks). Forty-three were wounded: three officers and forty ORs with 241 Bty taking the brunt. Brig. R.J. Lewendon wrote in the Journal of the Royal Artillery (1981) that thirty men of the 77th RA died as the result of the accident and 100 were injured. Fifty gunners from the 6th HAA (Heavy Anti-Aircraft) were transferred to the 77th following the rail crash.]

Unfortunately, my fellow Battery Sergeant Major (BSM), Ken (wyn) Street, was also killed. As a result of this tragedy, I’ve been commissioned to second lieutenant and set to be posted to Soerabaja to help replace killed and injured officers.

7 February

I continue to help organise the artillery defence of Tandjong Priok with the Dutch KNIL. Unfortunately, no proper replacement parts can be found for damaged and missing gun counter-balance springs so we’ve requested the REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) make suitable improvisations. We’ve heard that Soerabaja (Sidotapo) has been taking a real pounding. (It was later confirmed that fifty-one artillery men had been killed and fifty injured). [The Regimental HQ was established at Tandjong Priok railway station.]

9 February

The bombing has intensified. We blasted away with partial success, though I do not know how many aircraft we actually shot down.

10 February

I’ve received orders that I will finally be proceeding to Soerabaja to replace the lost and injured officers of 240 Bty. I am to be the OC (officer-in-command) of the convoy to take replacement artillerymen by road. We’ve been warned about saboteurs and to keep a close watch on vehicles at night. In addition, Japanese fighter planes are hitting road convoy vehicles. Although the jungle canopy has proved very helpful as extra camouflage, the Japanese do seem to be aware of the movement of our road convoy!

11 & 12 February

There’s been a lull in the bombing (it was later confirmed that the Japanese were concentrating on the capture of Palembang in southern Sumatra, so air attacks decreased significantly on Java for the next four days). GHQ (General Head Quarters) confirmed the decision for me to transfer to Soerabaja. Many evacuees are arriving from Singapore and Sumatra to Tandjong Priok – these are mainly civilians and RAF personnel, but, unfortunately, with no useful equipment.

I proceeded to Soerabaja, a journey of over two days by road, and arrived there late afternoon. Fortunately, we did not come under attack and there was no overheating of vehicles – another concern for lorry convoys. [According to Humphries, at 0900 hrs on 12 February the main guns and heavy equipment left Batavia for Soerabaja under the command of Capt. J. Mellor (RAOC). Lt Col Humphries and his adjutant flew to Soerabaja after supervising the despatch.BSMRonald Williams was promoted to 2/Lt and transferred to 240 Bty. Sgt [Sergeant] Cecil West and Sgt Adrian Davies were promoted to 2/Lts, 241 Bty; Lance Bombardier (L/Bdr) Frederick Fawcett promoted to 2/Lt, 240 Bty.]

13 February

Capt. G. Smyth took the remainder of the convoy to Soerabaja (small fast vehicles).

15 February

More bad news – we’ve heard that Singapore has fallen and Palembang (southern Sumatra) has also been captured. This places Java in a precarious position. A fresh wave of bombing on Soerabaja has commenced; things are beginning to look ominous.

16 February

I was transferred, by motor launch, with a small party of artillery-men, to Kamal, near Bangkalan, Madoera Island, east of Soerobaja. The island contains KNIL batteries and a secret radio station. Japanese attacks are expected imminently on Bali and Timor. [According to Humphries’ records, Right Troop of 240 Bty was to occupy a site on Madoera Island. Two 3.7-inch guns were transferred on 20 February and two further heavy guns on 21 February.]

[There is no further information about Ronald’s activities till 28 February. However, he wrote a play, One Came Back Home, a small extract of which follows as Appendix 6 in Part II, which gives a flavour of what might have been happening on Madoera Island.

Madoera had a Dutch artillery battery (12 x 78mm guns), and a secret radio station. It was also a forward observation post for the detection of a likely Japanese invasion by sea from the east of Java.

Although the Japanese had used paratroopers for invading some of the East Indies islands, Java was considered to be unsuitable for a major paratrooper landing, with the exception of the airfields, due to dense jungle and volcanoes. Seaborne invasion was thought most likely, coming from the west, east and south. The north coast, ultimately a major invasion point, was considered less likely owing to poor roads and jungle obstacles – but this, in fact, proved to be no obstruction to the Japanese invasion.

17 February

The Japanese Naval Force was heading for Bali, through the Makassar Strait. Allied submarines should have been a major force in combating the Japanese invaders but were unfamiliar with local waters and, in fact, USS Sea Wolf ran aground. Torpedoes fired by Allied submarines largely missed their intended targets and Allied B-17 bombers scored few direct hits on Japanese naval vessels.

18 February

The Japanese invaded the island of Bali. Unfortunately, Dutch troops left the airfield intact and as a consequence there were increased enemy bombing sorties over Java. The ill-fated Battle of Badoeng Strait commenced. (This is well documented in naval warfare history.) The 77th Artillery in Soerabaja shot down five or six enemy aircraft on this day and escaping Allied artillerymen arrived from southern Sumatra, minus their guns!

19 February

Fresh and heavy bombing recommenced on Soerabaja, from southern Sumatra and Bali. There was dog fighting over Java, reminiscent of the Battle of Britain. The Allies lost seventy-five aeroplanes. Air defences were becoming very thin and ground defences were under severe pressure. Radio silence was maintained on Madoera for the Battle of Badoeng Strait.

Unfortunately, tactical errors by Rear Admiral Karel Doorman’s ships led to severe setbacks. The use of close-range artillery was ineffective and Dutch destroyers, employing searchlights at night, lost any element of surprise.

Unlike the Allies, the Japanese had been well trained for night fighting. Ideally, some Allied warships should have been kept in reserve, and repaired, for the anticipated Battle of Java Sea, which may have tipped the balance back in the Allied fleets’ favour. There were no aircraft carriers available and, therefore, deployment of aircraft proved difficult.

20 February

The Battle of Badoeng Strait was effectively lost by the Allies. All airfields supplying Java were now in enemy hands. There were Japanese landings on Timor.

21 February

An Allied naval force left Batavia to head for Soerabaja. The De Ruyter and Java (Dutch light cruisers) and Houston (US heavy cruiser) joined the Eastern Strike Force in Soerabaja.

22 February

Overall military command was handed over to the Dutch East Indies’ Army chief, Gen. Hein ter Poorten. Churchill had communicated to Wavell to fight on – but no reinforcements would be forthcoming, as these would be sent to Burma and India. Churchill signals, ‘I send you and all ranks of the British forces who have stayed behind in Java my best wishes for success and honour in the great fight that confronts you. Every day gained is precious and I know that you will do everything humanly possible to prolong the battle.’ General ter Poorten stated that it was ‘better to die standing than live on your knees.’

The records of Lt Col Humphries state that Brig. Hervey Sitwel, commanding the 16th AA Brigade, when inspected the gun sites in Soerabaja. 240 Bty, on Madoera Island, saw them shoot down two enemy aircraft.

23 February

ABDACOM (American, British, Dutch and Australian Command), formed at the Washington DC Conference in December 1941, was dissolved and Wavell headed for New Delhi on 1 January to set up command in Java at Lembang. Brig. Sitwell was promoted to major general and became general officer commanding (GOC) of all British forces.

24 February

A number of senior Allied officers left Java for India and Australia. A large Japanese naval force was reported to be heading through the strait of Makassar towards Java. West and east Java were reasonably well defended, but most of the north of the island was undefended. Gen. Sitwell felt that forces should be concentrated in the west, east and south to delay the enemy invasion as long as possible.

Unfortunately, there were a large number of military non-combatants, mainly RAF, on Java and time was considered much too short to train them for combat. The Dutch were being heavily relied upon for communications but these were becoming increasingly fragmented across Java.

A further concern was the use of a wide variety of ammunition calibre for light weapons (each nationality had different calibre ammunition), which produced considerable problems in re-supply. Gen. Sitwell moved some of the LAA (Light Anti-Aircraft) Btys from Soerabaja to defend the airfields of Malang and Madion.

240 and 241 Btys stayed in Soerabaja. Batavia received a heavy bombing raid with six Japanese raiders shot down.

25 February

Rear Admiral Doorman set sail from the Dutch Royal Naval base of Soerabaja, and Dutch Admiral C.E.L. Helfrich sent HMS Exeter, Perth (Australian Navy), Jupiter, Electra, and Encounter (British destroyers) from Batavia to join Doorman. A sweep of the sea area north of Java took place and a Japanese convoy was sighted near Bawean Island.

26 February

Admiral Doorman intercepted Japanese troop carriers with limited success, causing damage and slowing their progress. In addition, American bombers destroyed some troopships and a US submarine destroyed the Japanese radio station on Bawean.

Churchill wired Admiral Maltby (Senior British Naval Commander) to continue fighting for as long as possible: ‘Every day gained in the defence of Java is precious.’

Humphries’ records state that AA Brigade HQ ordered that 77th HAA Regimental HQ and 240 Bty proceed to defend Tjilatjap, in the south, leaving 241 Bty to defend Soerabaja under Dutch command. Most of 240 Bty left Soerabaja at 1130 hrs on the 26 February and arrived in Tjilatjap on 1 March.

27 February

This day was probably the turning point of the defence of Java, as the Battle of Java Sea commenced. (The Java Sea battle is reviewed in Part II, chapter 2.) There were major Allied losses. The Dutch cruisers, De Ruyter (Flagship), with Rear Admiral Doorman, Java and Kortenaer were sunk, as were the British destroyers Electra and Jupiter. Houston (‘the galloping ghost of the Java coast’) and Perth (Australian Navy) managed to return to Tandjong Priok and the battle cruiser Exeter was badly damaged.

Later there was heated debate as to why the battle had gone so badly wrong for the Allies – some of the main reasons identified were the following:

•The Japanese had mostly modern warships with accurate long lance oxygen-driven torpedoes, which they used to great effect.

•The Japanese were also a more efficient fighting force and outnumbered the Allies.

•The Allies had incompatible communication systems and were a disparate group of warships.

•Many of the Allied ships had previously been damaged and remained un-repaired.

•The Allied men were extremely weary.

•There was almost a total lack of air cover for the Allies by this time and poor air reconnaissance.

•The Allies had no aircraft carrier; USS Langley had been sunk earlier.

•There were increasing fuel shortages.

Despite all of this, it was felt the Japanese invasion had been delayed by two days as a result of this sea battle and some felt that the two weeks the Japanese took to overrun Java prevented intended Japanese landings on northern Australia.

28 February

I returned from Madoera to Soerabaja. There have been orders to move 240 Bty to Tjilatjap, south Java, to defend the main port and airfield. The Japanese commence landings in the west and north. However, before moving artillery from Soerabaja it accounted for at least sixteen enemy aircraft. The plan is to leave 241 Bty, 131st US Field Artillery (Texan National Guard) and the Australian Pioneer Corps to defend Soerabaja and the airfield at Malang. Right Troop has set off for Tjilatjap

[Humphries: there were problems moving equipment and heavy guns off Madoera Island. Maj. L. Street visited to try and sort it out but could not obtain suitable transport. Later Maj. Gerald Gaskell and Capt. Fobber (Dutch Liaison Officer) managed to obtain two reasonable sized barges.]

Unfortunately, HMS Exeter, whilst escaping from Soerabaja, has been sunk. Destroyers, HMS Encounter and USS Pope suffered a similar fate. A strong Japanese force, with light tanks, landed at Ereten Wetan near Soebang, north Java, and make rapid headway inland.

1 March

RHQ, 240 Bty arrived at the port of Tjilatjap. The Japanese have landed at Kragan, on the north-west coast; there was still some air defence from Madioen, but unfortunately, Kalidjati airfield has been captured (with heavy losses for 48th LAA Regiment and 6th HAA Regiment, Royal Artillery). Also, on this inauspicious day, Houston and Perth were sunk by Japanese destroyers after entering the Sunda Strait and running into a major Japanese invasion force off Batavia.

2 March

Right Troop of 77th HAA arrived at Tjilatjap. We’ve learned that some of 241 Bty were cut off by the Japanese invasion of Soerabaja and have been captured. Roads to Tjilatjap are now seriously congested with fleeing colonials and other civilians. The convoy suffered some damage from air attacks. So far we have not met any opposition on land.

3 March

We rapidly set up defensive gun positions. Right Troop, 240 Bty deployed three 3.7-inch guns on a creek west of Tjilatjap (No. 3 gun-site). The gun-sites immediately came under attack from Japanese bombers and fighters. 239 Bty was moved from Batavia to defend the Bandoeng district. (The Japanese also attacked the Australian mainland at Broome, a north-west Australian port, destroying all Allied military aircraft and flying boats containing civilian escapees from Java.)

4 March

All hell has broken out! One main defensive position is a large football field north of the docks and here there was major action, with waves of attacks from Japanese dive-bombers with low-level bombing and Zero/Zeke fighters strafing the gun-sites with machine-gun fire. The port also came under fire from naval bombardment, with many ships being damaged or sunk. One of our gun emplacements (four guns) took a direct hit. An estimated ninety [Humphries’ report puts the figure at 150!] Japanese medium and light bombers and fighters were attacking us. We shot down in excess of fifteen enemy aircraft and damaged others. The brave Bren gunners did a sterling job in keeping the Jap Zeroes at bay, a number of whom lost their lives and others were seriously injured in the process. The docks have also been heavily bombed.

5 March

We are all bloody exhausted! Further heavy aerial bombardment has continued from planes and ships, though we’ve again had reasonable success in shooting down aircraft, about the same numbers as yesterday. We’ve heard that Batavia has been over-run. There were three major invasion points on Java, west, north, and east of the island (at Merak, Ereten Wetan and Kragan), by the Japanese 16th Army under Gen. Imamura. All ships in Tjilatjap harbour have been sunk.

It appears that there was little resistance in the north, where the airfields were quickly over-run, although there was brave defence of Kalidjati airfield by British soldiers and RAF men, resulting in most of the airmen being killed in action.

[Research by Brig. R.J. Lewendon, on behalf of the Royal Artillery Institution, indicates that during the period 3–5 March, twenty-six Japanese planes were definitely destroyed and thirteen probably destroyed by British artillery fire.]

6 March

We are dog-tired. The Japanese continue to advance rapidly. There have been problems with the Dutch Army abandoning useful equipment and failing to destroy both guns and trucks, which then fell into Japanese hands, so we were ordered by Gen. Sitwell to destroy or disable all our heavy equipment. We successfully spiked (exploding and splitting gun barrels) all our big guns and smashed instruments – a sad sight! We are still fighting with Bren guns mounted on any tripod that could be constructed. It appears that we are heading for Tasikmalaja airfield, to fight on with light weapons. Things are looking ominous!

Lt Col H.R. Humphries had a major altercation with the local Dutch commander at Wangon crossroads (a small town between Tjilatjap and Purwokerto), where we ran into the Dutch force moving up from Tjilatjap. ‘Col Bob’ tried to persuade the Dutch commander (probably Maj. Gen. Pierre A. Cox) to join forces, but it was clear the Dutch were not keen to fight on, as they thought the situation had become hopeless. (‘Col Bob’ later wrote that his entire regiment was adequately armed with light automatics, Thompson machine guns, and rifles and could have rendered an excellent account of themselves should any opposition be encountered. However, despite repeated efforts, the Dutch commander could not be persuaded to join forces, saying he had ‘no orders’ to fight on). [According to Humphries, the Wangon crossroads incident happened on 7 March. Despite their ‘adequate’ arms, Ronald said that the only time he actually used his service revolver during his time on Java was to put down a seriously injured horse! Although he and a number of his battery did take turns at firing ‘pot-shots’ at low-flying Jap aircraft with Bren guns to display continuing resistance.]

7 March

We’ve learned that the Dutch are on the point of capitulation, as the Japs now occupy Tjilatjap and Lembang, thus blocking the final escape route from Java. (Dr Hubertus van Mook, the head of government on Java, and some of his cabinet, just managed to escape to Australia. Van Mook set up a government in exile in Adelaide. He complained bitterly about the lack of Allied help on Java.) It seems to be a case of just heading for the mountains, Tjakadjang, to continue fighting.

There was a radio broadcast from Gen. ter Poorten, stating all Allied resistance was to cease. Our top brass are not happy with this and Maltby is keen for continued guerrilla-style warfare. However, the options are not great for us, as we’d need to rely on the local Javanese for support. We are seen as part of the increasingly disliked Dutch colonial set-up and the Japanese already have a terrible reputation for killing civilians when they are known to be supportive of any sustained enemy resistance. There are also too many Allied military non-combatants (the RAF referred to them as ‘penguins’ if they were non-flyers). There are also Japanese informants and spies on the island. If the Dutch and Javanese do not fight on, then our position will become untenable.

8 March

The Dutch have formally surrendered (Tjarda van Starkenborgh, the Island’s Governor General, to Gen. Hitoshi Imamura) at Kalidjati. At 1000 hrs, we ended up in Garoet, in the middle of Java, among rubber plantations. (This would become the main assembly point for prisoners of war before being sent, via rail or truck, to internment camps in Batavia.) [Humphries: At 1200 hrs a rear guard, comprising three officers and fifty men, was posted to hold the road until 239 Bty arrived. This was withdrawn once the capitulation order came through. All light weapons destroyed (LMGs and sub-MGs).]

9 March

At 1430 hrs Admiral Maltby and Maj. Gen. Hervey Sitwell surrendered to the Japanese commander at Bandoeng. Apparently the Japanese had threatened to flatten Batavia if the Allies failed to unconditionally surrender. There was little evidence of Japanese soldiers in our area at this time.

The regiment went to Tjisompet through mountain roads.

10 March

[Humphries: Some men had made a break for it, causing a great deal of consternation. The situation was retrieved by Maj. F. Baddely, RA, before any Japanese reprisals could take place.]

11 March

We were given orders to stack all weapons and ammunition for inspection (many weapons were rendered useless by their owners, in defiance of surrender terms, so that they would be of no value to the enemy) and be prepared for a big roundup. Battery unit diaries, codebooks, maps, etc., were destroyed. We had to set up a perimeter area, although there is still reasonable freedom of movement, providing a white armband is worn.

We are billeted in estate buildings and lorries on a Dutch rubber plantation at Tjisompet, near Garoet.

The occasional pair of Imperial Japanese Army soldiers appear, menacingly waving their rifles with fixed bayonets and sometimes hit and slap people for little or no reason. (This was our first indication of what was to come. Japanese soldiers were regularly beaten by their superiors. These soldiers viewed prisoners of war as subordinates and fair game for similar treatment.)

On a plantation in Java,

Far away from England’s shore,

We lead a life of peace and quiet

After this stress of war.

When we were gathered together,

We learned the Glorious 77th

Had lost a Battery and a half

From its total strength of three.