Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

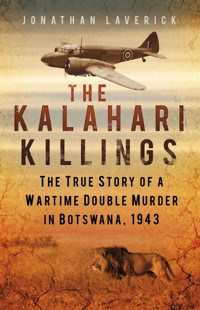

On 4 October 1943, two trainee RAF pilots, Walter Adamson and Gordon Edwards, took off from Kumalo in Zimbabwe. Some time later they were forced to land in Botswana. They climbed out unscathed, left a note, and disappeared. What happened next would entail ethno-archaeological investigation, a sensational murder trial with worldwide media coverage – and an astonishing outcome – that led to a profound change in the lives of the Tyua Bush people. The airmen had been murdered by bullet and axe – but why? Twai Twai Molele, the leader of the group of eight killers charged, was known to be a witchdoctor and a bottle allegedly containing human fat was found in his possession … Following the trial the Tyuas' guns were confiscated and their ageless, nomadic hunting life began to die out. The murders offered an excuse for British-protected cattle farmers to remove them from their lands. Reopening this extraordinary case, Jonathan Laverick reviews the evidence to uncover the true story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Introduction

Part 1 – Training

England, 1940

Bechuanaland, 1940

Scotland, 1941

Bechuanaland, 1941

Russia, 1941

Bechuanaland, 1941

Egypt, 1942

Bechuanaland, 1943

Rhodesia, 1943

Part 2 – Missing

RAF Induna

RAF Kumalo

Final Flight

Part 3 – Search

Overdue

Missing

Part 4 – Trial

Lobatsi

Monday 25 September

Tuesday 26 September

Wednesday 27 September

Thursday 28 September

Friday 29 September

Summary of the Case for the Prosecution

Summary of the Case for the Defence: Kelly

Summary of the Case for the Defence: Fraenkel

Judgement

Part 5 – Aftermath

The Royal Air Force

‘A Striking Example of British Justice’

Talifang

The Edwards Family

‘The Ten Thousand Men’

Part 6 – Postscript

Tshekedi Khama’s Downfall and Seretse’s Rise

Impact on the Bushmen

Twai Twai

The Ten Thousand: Rre Molatlhwe

RATG

Gordon’s Fiancée

The Hurricane of the Lake

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

I first came across this story when researching the history of a Tiger Moth owned by one of the parents of a student of mine, here in Botswana. The little de Havilland trainer was important because a brief internet search led to the story of the murder of an RAF pilot by giraffe-eating Bushmen after crashing his Tiger Moth. It was a bizarre tale that had all the elements of a good book, even if, as I was to find out, most of it was wrong.

Hooked, I started to dig deeper and quickly found that multiple versions of the same tale existed, but the details changed with each new version I unearthed. Indeed, Tony Park’s novel African Sky opens with a pair of Bushmen murdering a Harvard pilot in Bechuanaland. Fortunately, my search coincided with that of Chris Watkins in England, who was building his family tree. He had had a great uncle ‘that had flown Spitfires in the war’, but when he applied for Gordon Edwards’ records he found that he had been killed while training in Rhodesia. More research on his part discovered that Gordon had in fact been the centre of one of the strangest murder cases in African history. Not only that, but the story had been the subject of an academic paper by an American professor.

Robert Hitchcock is one of the world’s leading authorities on indigenous peoples, especially the San of southern Africa. In 1975, however, he was a young researcher who had too much time on his hands during his stays in Gaborone, the capital of Botswana. He spent this free time in the Botswana National Archives looking into issues that involved Bushmen. One file that caught his imagination was that of Rex v. Twai Twai Molele et al. as it included a lot of information, including diagrams, on how the Tyua group of Bushmen had lived and hunted in the early parts of the twentieth century. This formed the basis for his paper entitled ‘Kuacaca: An Early Case of Ethnoarcheology in the Northern Kalahari’.The file also told the story of the fate of Gordon Edwards and his co-pilot, Walter Adamson.

Having made contact with Chris and Bob, the next step was to visit the national archives in Botswana to see whether the court documents were available. The good news was the case notes existed still, but the bad news was that they were in the process of being moved when I first applied to see them. While waiting for them to be found, I started going through files only loosely connected to the case and I found a lot more information about how nearly 10,000 men from Botswana had volunteered to fight in the Second World War. The aftermath of the trial was also discussed in detail, as it came close to causing a major diplomatic incident, if not a minor war of its own.

When the court documents surfaced, all 240 pages of them, I was amazed by what I found. Having lived in Botswana for sixteen years and enjoyed its friendly, easy-going atmosphere, it was hard to match the casual brutality of the alleged murders with my experience of the country. It was also hard to believe that the High Court in sleepy Lobatse was once the focus for the world’s press, with the story of the murders appearing in newspapers all over the Empire. That coverage was itself a testament to the curiousness of the case. The fact that the trial got such extensive attention while Allied troops were still fighting their way through Europe was another indicator of the sensational nature of the killings.

Contact with various ORAFS (Old Rhodesian Air Force Sods) added detail to the Rhodesian Air Training Group’s role in teaching nearly 10,000 pilots from across the Empire during the Second World War, while a visit to the RAF Museum’s reading room gave access to the training syllabi and a range of log-books that belonged to Gordon Edwards’ contemporaries. The National Archives at Kew added the London side of the story as well as more newspaper coverage from the era. Tracking down suitable photographs also took up some considerable, but thoroughly enjoyable, time.

Finally, a visit to Bulawayo and the airfield Gordon had last taken off from, and a trip to the salt pans in northern Botswana where he lost his life, completed my research. My only disappointment was being unable to trace any surviving members of Walter Adamson’s family, the other pilot who was killed. Perhaps the publication of this book will lead to further information becoming available.

I would like to thank the following, in no particular order, for their help and assistance during the production of this book. Joanna Poweska, my wife, for her undying support and encouragement. Robert Hitchcock for his endless knowledge and his willingness to share his research to an amazing extent. Chris Watkins and the Edwards family for their enthusiasm for the project, along with the time and information they donated. Tony Park, for sharing his sources so quickly, The National Archives of Botswana and The National Archives of the United Kingdom, two institutions that could not be any more different in terms of size and technology, but which are both full of the most interesting documents and are staffed by the most helpful people in the world, something appreciated by nervous first-time visitors. To those who were willing to share photographs, often from departed loved ones, usually only asking for credit for fathers or grandfathers, I am especially grateful. The late Eddy Norris certainly deserves a mention. Finally, to all those that take the time to maintain websites that commemorate those that made such big sacrifices during the Second World War, a big thank you, both for sharing information so easily, but also for keeping alive the memories of those who barely made it out of their teens over seventy years on.

Incidentally, the Tiger Moth that started this story was an ex-Indian Air Force machine. If I had found that out sooner, this would have been a very short book.

A Note on Language

Setswana is not the easiest of languages to learn and I would not wish the reader to lose too much enjoyment from its overuse. However, the following explanations may be of some use.

The plural is usually given by Ba and singular by Mo. So the people of Botswana are Batswana, the people of the Ngwato tribe are Bangwato. A single Batswana is a Motswana. Dummela is the usual greeting, almost always followed by Rra or Mma (sir/madam).

In the text I refer to Tswana kings and chiefs and these can be considered interchangeable. The Setswana word Kgosi certainly implies royal blood, but the British administration tended to use ‘chief’ for reasons that were then obvious.

The Bushmen go by a variety of names and the reasons for this are explained later. The word ‘Bushman’ did at one point go out of favour, but many Bushmen find the alternatives no friendlier. The Setswana term Sarwa is used in some parts, with Mosarwa being singular and Basarwa plural. Other common alternatives are San or Khoi-San. The major problem with all of these terms is that they are often used as a catch-all phrase to describe often quite different groups of people.

Place names are given as those at the time of the incidents described, so Botswana is usually described as the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

TRAINING

ENGLAND, 1940

On 23 May 1940, a Miles Magister skimmed its way toward Calais at very low level on a desperate rescue mission, its escort of two Spitfires slightly above and behind, the cold waves of the English Channel barely a couple of feet below.

The two-seat trainer was on its way to pick up the commanding officer of 74 Squadron who had found himself marooned in France in the middle of a huge and chaotic retreat. His own Spitfire had been forced down hours earlier by a Messerschmitt Bf 109, as his squadron tried to protect the British troops heading for the small port town of Dunkirk. Experienced pilots were so valuable to the Royal Air Force at this point that the order for his recovery had come from the very top of 11 Group.

Leatheart, the pilot of the Magister, made a textbook landing, and picked up his passenger before opening his throttle wide. The trainer picked up speed, bounced and was airborne. Instantly there was the rat-a-tat-tat of machine-gun bullets hitting the small plane. Leatheart cut the engine and slammed his craft back down to earth as a 109 flashed past. As the German climbed past, smoke billowed from its engine before it rolled over and dived into the sea with an almighty splash. Another 109 hit the ground inside the airfield perimeter as Leatheart and his shaken senior passenger threw themselves hurriedly into a rather muddy ditch. A Messerschmitt roared down out of the clouds with a Spitfire on its tail before the gloom swallowed both of them again. In the distance an explosion marked the end of the last 109. After waiting for five minutes, the Magister set off again to deliver its valuable cargo to RAF Hornchurch.

A Miles Magister, as flown by Leatheart on his daring mission to rescue his CO. (Doug Claydon/New Dawn images)

Al Deere was the pilot of one of the escorting Spitfires that claimed two of the 109s and he was a perfect example of the reach of the British Empire. A New Zealander who had joined the RAF three years before, he had only been flying Spitfires for five months, but he was already becoming something of a star.

Deere was fortunate to have made it even this far in his flying career, lucky not to have been killed in an air crash two years earlier. A keen amateur boxer, he had been selected to join the RAF team that was going to tour South Africa. Fortunately for him, his flight training took precedence and he remained in England. Fortunate because, after competing in Bulawayo, one of the three South African Air Force Airspeed Envoys carrying the team back to Pretoria disappeared amid heavy cloud over the Limpopo River that marked the border with Bechuanaland. After an intensive search, the wreckage and bodies of the six crew and passengers were found just inside the protectorate at Balemo. The accident claimed a final victim when one of the Bechuanaland Protectorate policemen, who was part of the search party, cut himself badly during the search. The officer, Dennis Reilly, developed gangrene and died not long afterward.

Within a week of the daring Dunkirk rescue flight, Deere himself was shot down over Belgium by a German bomber he was attacking and had to make his way home on foot via the evacuations at Dunkirk. This cannot have been an easy journey because at the time the RAF was not popular with the army, who felt the air force was not doing enough to protect the troops on the beaches and feelings were running high, to say the least.

Al Deere was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), along with the other two rescue pilots, on 12 June 1940 with his citation making mention of the fact that he had already, even before the Battle of Britain started, shot down five enemy aircraft. Despite writing off nine aircraft, either crashed or shot down, Al Deere finished his career in the RAF as an Air Commodore in 1967, having added a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and a bar to his DFC.

Perhaps it was the heroics of Deere, and others like him, that encouraged a 19-year-old Welshman by the name of Gordon Edwards to join the RAF. The lure of excitement and adventure must have been tempting to the blue-eyed, brown-haired, lanky teenager who was about to start a career as a clerk in the small town of Porth in Glamorganshire.

Gordon Edwards was born on 25 April 1921 in the small village of Ynyshir and he was the pride and joy of his mother, Sarah. Ynyshir, on the Taff Valley Railway, consisted of little more than a square of miners’ cottages. Nestled in the Rhondda Valley, it was a typical of the colliery settlements that had sprung up on previously sparsely populated agricultural land. Despite its small size, the village boasted several churches of various dominations, but Gordon’s English mother took him to Porth to have him baptised into the Church of England.

Originally from Birmingham, Sarah Edwards had moved to South Wales with her Scottish husband. However, the union was not a happy one and Gordon was brought up by his mother in the small village of Pontylclun, farther down the valley towards Cardiff. This small hamlet had consisted of only four or five households before the coming of the South Wales Railway in 1851, which opened up commercial opportunities for mining, and by the end of that decade there was a flourishing colliery and iron mine in operation. This drew workers from far afield, particularly from Cornwall where the tin-mining industry was in terminal decline. By the turn of the century it had developed into a small, but bustling, working-class industrial town boasting both rugby and football clubs. As well as mining, there were various light industries, including a brewery producing several hundred barrels of beer a week to quench the thirst of the miners.

Despite separating from her volatile husband, Sarah never divorced, and brought up Gordon and his elder sister, Muriel, alone. At the same time she looked after her widowed father who lived with the young family, creating what must have been a tightly knit unit. Certainly Sarah developed a reputation of being a strong-willed and tough woman, typical perhaps of many such women in mining villages up and down the country. Despite the presence of her father, nobody was left in any doubt that she was the head of the household.

Sarah’s brother had followed her to Wales from Birmingham and was working as a chauffeur at the nearby Miskin Manor. Although claims of a manor at the site went back nearly a thousand years, the current building dated to 1864 when David Williams built the large Tudor-style mansion. According to local legend, the Williams family had made significant money from South African gold, as well as having interests in the regional iron ore mines.

Gordon was a tall but thin young boy who was protected by his mother, who considered him too frail for a future in the mines. Indeed, Sarah Edwards considered the local schools too tough for her favourite child and a combination of her will power and Gordon’s academic ability saw him win a place at Cowbridge Grammar School, where he appears to have done well. His mother’s pride was immense, especially as she was well aware of the fact that her own education had ended at the age of 10. Despite his mother’s fears, Gordon obviously got caught up in some youthful scrapes as his later service records mention a scar below his right eye, two scars on the back of the scalp, as well as further scarring to both knees.

During his time at school, Sarah decided to move the family to Miskin. This move suited Gordon as he could join the Miskin Manor Cricket Club. During school holidays he played in the youth team alongside Glyn Williams, the heir to the Williams fortune. This fortune was obviously quite significant as the manor had been rebuilt after a serious fire in 1922 without too much interruption. By the end of his schooling, Gordon got the occasional game for the senior team. This was quite an achievement as the small village team had developed an impressive reputation, despite its limited facilities. Gordon would have changed, and for that matter taken lunch and tea, in tented facilities while taking on special guest teams, including Glamorgan County. The scorers had slightly better accommodation, being homed in an old toll house that had once stood at the entrance to Pontyclun. The cost of the relocation had been met in full by Sir Rhys Williams. It is clear that Gordon had a passion for the game, while his mother no doubt appreciated the fact that cricket matched her goals for her son, much more than football or rugby would have done. The make-up of the pre-war Miskin team is socially interesting, comprised as it was of miners’ sons, a police sergeant and the heir to a mining fortune who had just finished his schooling at Eton. Dai Hammond made several centuries for Miskin before being called up for Nottinghamshire.

By the time Gordon left school, his sister was already married with a daughter of her own. Gordon became very close to her in-laws and extremely fond of his niece, Rosalind. Tall and handsome, his dark hair setting off his blue eyes, the young Welshman was blossoming. Yet by the time of his eighteenth birthday, it was clear that the storm clouds were gathering and that the world would soon be plunged into a conflict that would dwarf the Great War of his parents’ generation.

Three weeks after Dunkirk, Gordon found himself at the RAF recruitment centre at Uxbridge, having travelled to London without telling his mother. In fact, he had had a service medical a week earlier and had been declared Category II, which ruled out any idea of being a pilot. The next eight weeks saw him shuttled between various processing centres while the Air Force decided what to do with the young Welshman. This gave Gordon several opportunities to visit home and give Sarah time to get used to the idea. It can be assumed, that after her initial shock, his mother did not share Gordon’s disappointment at being kept on the ground. With the Battle of Britain underway and pilots being lost or, worse in many eyes, burnt unrecognisably, ground crew must have looked a safer option to Mrs Edwards.

Eventually, towards the end of September, Gordon was sent to No. 6 School of Technical Training at RAF Hednesford. This camp was situated seven miles outside of Stafford and was a relatively new facility, having only being completed the previous year. It was a huge site, with its own hospital, post office, cinema, two firing ranges and three churches, but it had no runway and consequently no airworthy aircraft. It was intended to be a short sharp shock of an introduction into service life, with discipline forming a large part of this. Marching, drills, physical exercise and general ‘square bashing’ were combined with education. In Gordon’s case this was mechanical, learning the basics of how to service, maintain and fix the latest technological masterpieces that formed the Royal Air Force’s front line. Many of his instructors were graduates of RAF Halton, home of the original apprentice airmen scheme. This training centre had been set up by Hugh Trenchard in the 1920s to ensure a supply of highly trained ground crew and enjoyed a remarkable reputation, its alumni being universally known as ‘Trenchard’s brats’.

Although Hednesford was new and had good amenities, accommodation was still basic. Gordon would have shared a large wooden hut with nineteen other raw recruits, something of a shock for a young man who had been considered too frail for his local school. This certainly was something of a coming of age. He would have met men from all over the UK and Gordon would have learned to make friends quickly. The village of Hednesford was within walking distance and the local pubs would have played their part in this male bonding.

After four months intensive training, Gordon Edwards left the Technical School as a qualified mechanic. In addition, he would have had a better understanding of RAF traditions.

BECHUANALAND, 1940

A small dot moved slowly across the huge metallic blue dome that formed the roof to the Kalahari Desert. The modern aeroplane, thousands of feet above the sand, merely served to emphasise the unchanging land known locally as the Kgalagadi or ‘The Great Thirstland’. A country similar in size to France, Bechuanaland was home to less than 250,000 people in 1940 and the landscape gave clues as to why this was so. The vast Kalahari covered nearly four-fifths of the protectorate, with rain being limited to the devilishly hot summer months that ran from October to April. Only in the top western corner did the magnificent inland delta of the Okavango give any relief from the stunted bush that dotted the rest of the country.

Bechuanaland had always been something of an outlier in the British Empire, and visitors often left its barren land with the feeling that it had remained a separate country largely because nobody wanted it. This was especially true of anybody who came during the harsh dry season, when visiting British officials would look on in wonder at how any of the thousands of cattle could survive such conditions. This impression of ‘unwantedness’ was wide of the mark, however, and the story of how it became that rarest thing, a British Protectorate, is a fascinating one.

The Tsodilo Hills that mark the far north-western corner of the country had been inhabited for at least 19,000 years, with evidence left in caves by generations of the original inhabitants. These were the San, the Baswara, the Khoi or simply the Bushmen, and for the next 17,000 years they were the sole guardians of the land, but the next two millennia would see them forced into the harshest parts of the country or become little more than serfs and all but written out of history.

Often thought of as hunter-gatherers, these first inhabitants had, by the second century AD, started to keep livestock, definitely sheep and probably cattle, and some groups started to live in settled villages. While hunting and gathering of wild food formed an important part of life, it was now a supplement to their livestock and crop growing. Knowledge of pot-making seems to have arrived at the same time as the domestic animals, and it is probable that these had arrived through trade with people from East Africa.

Perhaps following on from this trade, Bantu-speaking people started to trickle down both sides of the Kalahari around AD 300, bringing with them knowledge of iron working. Originally from the Cameroon region of West Africa, these black Africans had spread to the Great Lakes area and it was probably here that they acquired the knowledge of millet and sorghum, and possibly gained cattle too. Others had travelled down the west coast and probably relied more on goats. Few in number, they appear to have had peaceful relations with the already present Khoisan, trading and inter-marrying. There also seems to have been borrowing from each other’s beliefs and customs as the Bantu continued to spread south, into what is now South Africa.

The start of the second millennium saw a rise of competing Bantu chiefdoms. These involved various cattle-herding peoples who would supplement their food with meat gained from hunting. One major group settled around the Serowe area, with a capital at Toutswe Hill that supported kraals of cattle and goats in surrounding villages. The Toutswe would hunt into the Kalahari to the west and trade with the growing civilisations to the east. Shells from the distant Indian Ocean were used as currency in these early transactions, and these found their way all around the Kalahari region.

The Toutswe were eventually conquered by their trading partners, the Mapungubwe, sometime in the thirteenth century, but while Toutswe was abandoned, other villages survived. The Mapungubwe themselves would be soon incorporated into Great Zimbabwe, a civilization made rich by their control of the Shashe gold trade. Great Zimbabwe and its successor, the Batua state, controlled not only the gold trade but also salt from the great Makgadikgadi Pans. When this empire collapsed, the Batua people in Botswana became known as the Kalanga and inhabited the north-east of the country.

The scene was then set for the rise of the Tswana. By the seventeenth century the Sotho or Tswana people stretched from the Transvaal in modern South Africa to the current Namibian border. These descendants from the early eastern stream of Bantu settlers were now formed into related cattle keeping clans. As land was overgrazed they would move on to better pastures, eventually bringing them to south-eastern Botswana. These clans, tribes or merafe shared customs and a belief system based on a creator god, Modimo. Other lesser gods were spirits of their earliest ancestors. They also had a class-based system, led by the Kgosi, or chief, and the royal family. People from other Batswana tribes who had joined the merafe were next, followed by people from non-Batswana clans. The Khoisan were known for the first time as Basarwa and these were never admitted to the merafe. Instead, they were often treated as slaves, forced to work in the fields or to herd cattle for little reward. These groups varied in size, but the largest probably had around 10,000 members by around 1800. Despite this, the Batswana had little political or military might.

Difaqane is the name given to the disaster that befell the Batswana next. Literally meaning ‘hordes of people’ it might not be a perfect description, but it does give an impression of the chaos it brought. The causes of this dislocation were many, but all of them put inward pressure on the Batswana tribes. The slave trade was flourishing, and Maputo and Delagoa Bay on the east coast had become major centres in the trade of humans. There was money to be made and African chiefs were encouraged to raid each other for slaves, being armed by Europeans to do so. These raids also meant that crops and cattle were stolen. Griqua bandits raided the area just to the south of Botswana, often selling their slaves to white farmers.

Far to the south, Shaka Zulu’s reign caused panic in the tribes above his expanding empire. Many of these fled north and north-westwards, some travelling as far as Tanzania before settling. On their journey they raided Batswana settlements for food and cattle. Worse was to follow, as Mzilikazi broke away from Shaka’s rule with 300 warriors. On his way to the Magaliesburg Mountains, to the west of where Pretoria would be built, he collected a veritable horde of people. He cleared his new land of any potential enemies, including many Batswana. From here, Mzilikazi sent out raiding parties for both cattle and people. The Batswana clans could not cope with these constant raids and many broke into smaller groups and moved further into what would become Botswana. The whole region was full of small wandering bands of people, looking for food and safety.

The expansion of Dutch-speaking white farmers, the Boers, up from the Cape, avoiding British rule, was an additional pressure on the peoples of southern Africa. Believing in their God-given right to the land, some pushed as far as the Transvaal, settling on what appeared to be empty land. In fact, the region they chose had until recently been the home to Batswana before Mzilikazi had chased them away. Mzilikazi soon learned of the arrival of the Boers and sent two of his regiments to deal with them. Despite losing their cattle, by circling their wagons the farmers managed to survive this first attack. Relieved by a new party of Boers, the farmers went on the attack, aided by a significant party of Batswana warriors. The Batswana were officially there to help the white men recover their cattle but there must have been an element of revenge for them. Mzilikazi was being harried by Zulus to the south and a steadily increasing number of Boers to the east. He decided to make a move north, terrorising eastern Botswana as he passed through.

This disruption lasted for nearly fifty years, but by 1840 the Tswana kingdoms of the Ngwaketse, Kwena and Ngwato were in place to form the beginnings of a new state. These had been formed by chiefs gathering up their people, who had been spread far and wide by the troubles, and by incorporating smaller merafe. After the Difaqane the Kgosi realised that the only way to protect themselves from outside influences was to be well armed. The trade of ivory paid for guns, which allowed for more successful hunting. Soon the great elephant herds around the Orange and Molopo Rivers had been destroyed. This hunting moved gradually northwards, until there was no big game left in the southern half of Botswana. This growing trade route, which also saw fur and ostrich feathers make their way down wagon routes to the Cape Colony more than 1,000 miles away, also attracted missionaries. These included the famous Doctor David Livingstone. He was responsible for the conversion of King Sechele I, chief of the Kwena in Molepolele, although Christianity struggled to catch on with his tribesmen. Livingstone was also responsible for the first church and school to be built in Botswana, at Koboleng, not far from the current capital, Gaborone. These were destroyed by Boer farmers after they had fallen out with their recent Tswana allies.

A little further north, a German missionary by the name of Heinrich Schulenburg worked to convert members of the Ngwato at their capital, Shoshong. In his second year he carried out his first nine baptisms, which included Khama and Khamane, two sons of the king, Sekgoma. When the London Missionary Society (LMS) replaced the German in 1862, the two boys were enrolled in the school run by Elizabeth Price. Khama’s popularity and easy disposition were noted and he would become a star LMS pupil in more ways than one. However, political interference by the LMS almost cost him his birthright. The missionaries were frustrated that the king, Sekgoma, refused to convert and did not want to upset his ancestors by ending tribal traditions, such as initiations for young men and bride price for women. This, along with Khama’s marriage to a Christian, drove a rift between the king and his heir. With LMS help, Sekgoma was dethroned and a Christian outsider imposed; however, all this succeeded in achieving was the reconciliation between father and son, and together they soon had Sekgoma back on the throne. The peace did not last long and Khama took his followers to Serowe and from there launched an attack on his father. Within a month Khama was King Khama III.

With Shoshong becoming less fertile and suffering from unreliable water supplies, the Bangwato relocated to Khama’s new stronghold of Serowe. From here Khama became widely known as an enlightened leader, introducing new Western technology such as wagons and ox-drawn ploughs. He also stuck with his Christian faith, cracking down on initiation services and traditional beliefs as well as prohibiting alcohol from his territories. The LMS became the state church, with Khama banning other missionaries and the construction of competing churches.

Just as stability was restored, Khama was faced with two new problems in the form of competing Europeans. Germans were encroaching from German South-West Africa (modern Namibia), while Boers were making constant raids from the south-east, partly with an eye to possible gold fields. Khama appealed to the British who considered the Tswana as allies against the Boers, and a protectorate was declared in 1880. This initially encompassed the lands as far north as Khama’s kingdom before being extended to the Chobe River five years later, finalising the borders of Bechuanland. Somewhat amazingly, the newest country in the Empire was soon the scene of Britain’s first use of military air power when a balloon regiment was sent to help counter Boer raids in 1883.

Khama and his headmen around 1882. (Council for World Mission archive, SOAS Library – CWM/LMS/Africa Photographs Box 6 file 42 25)

The new country was still under threat though, this time from a megalomaniac Englishman. Cecil Rhodes was already using the road through Bechuanaland to reach Zimbabwe, soon to be Rhodesia, and had his eye on the empty spaces of the Kalahari. The LMS helped organise a direct appeal to the British people by shipping the three most important chiefs, Sechele I, Khama III and Bathoen I, to the UK. Here, assisted by W.C. Willoughby of the LMS, the three kings toured the country and caused quite a stir, as can be imagined. With public opinion on their side they returned home with a rare victory for Africans. Rhodes and the British South African Company had to settle for only land rights to build a railway through the eastern side of the country to Bulawayo.

Despite many Batswana fighting with the British in the Anglo-Boer war, the British Government maintained an arm’s length approach to the protectorate. With the formation of South Africa in 1910, the British promised that the three High Commission Territories, Bechuanaland, Lesotho and Swaziland, would one day be handed over to the Union. This terrified the Batswana chiefs, who had first-hand experience of how the Boers treated Africans. With the rise of Hertzog, and an increasingly racist Boer regime in the south, the British secretary of state for the colonies made a visit to the three territories in the mid-1920s. He left in no doubt of the view of the Batswana chiefs. Bechuanaland maintained popular support in the UK Parliament, despite the cost of an admittedly tiny administration, and a promise of consultation before any decision was made. Relationships between the administration and the chiefs were generally good, although the fact that the administrative capital was Mafeking, over the border in South Africa, gives some idea of how important the British considered the territory.

Khama III ruled until his death at 87 in 1923 when he was succeeded by his son Sekgoma II. Unfortunately, the new king survived in the post only a little over a year, leaving an infant called Seretse as heir. Given the new king’s age it was decided that Seretse’s uncle Tshekedi should act as regent – a decision that would have far reaching consequences.

SCOTLAND, 1941

A Hurricane flopped onto the grass runway and taxied in towards a waiting group of pilots, but they ignored its engine’s dying coughs as they gazed upwards in unison at the graceful shape approaching. They had waited a long time for this moment, and had been joined in their vigil by most of the ground crew. With a flick of its elliptical wing the newcomer rolled over and dived towards the airfield, sending the onlookers scattering in all directions. Loops and rolls followed before a perfect three-point landing saw the first of a new breed join 111 Squadron. The Supermarine Spitfire had arrived and Gordon Edwards was as excited as anybody else on the Scottish airfield.