9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

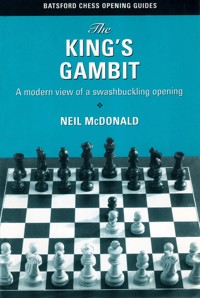

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The King's Gambit is the most daring and dangerous opening. White throws caution to the wind, and Black must know what he is doing to avoid early defeat. The King's Gambit was all the rage in the 19th century, but has an enduring popularity throughout the chess world. Remarkably, it is once more the focus of the top grandmaster attention, for example when Nigel Short played it three times in a row against the world's best at the Madrid 1997 tournament.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 333

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

1 e4 e5 2 f4

The King’s Gambit

BATSFORD CHESS OPENING GUIDES

Other titles in this series include:

07134 8456 X

Budapest Gambit

Bogdan Lalić

07134 8218 4

Complete Najdorf:Modern Lines

John Nunn & Joe Gallagher

07134 8467 5

Queen’s Gambit Accepted

Chris Ward

07134 8471 3

Spanish Exchange

Andrew Kinsman

For further details of Batsford Chess titles, please write to Sales and Marketing,

BT Batsford,

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd,

43 Great Ormond Street,

London WC1N 3HZ

or visit www.pavilionbooks.com

Batsford Chess Opening Guides

The King’s Gambit

Neil McDonald

CONTENTS

Bibliography

Introduction

Part One. King’s Gambit Accepted (2...exf4)

1 Fischer Defence (3 ♘f3 d6)

2 Kieseritzky Gambit (3 ♘f3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 ♘e5)

3 Other Gambits after 3 ♘f3 g5 and 3...♘c6

4 Cunningham Defence (3 ♘f3 ♗e7)

5 Modern Defence (3 ♘f3 d5)

6 Bishop and Mason Gambits (3 ♗c4 and 3 ♘c3)

Part Two. King’s Gambit Declined

7 Nimzowitsch Counter-Gambit (2...d5 3 exd5 c6)

8 Falkbeer Counter-Gambit (2...d5 3 exd5 e4)

9 Classical Variation (2...♗c5)

Part Three. Odds and Ends

10 Second and Third Move Alternatives for Black

Index of Games

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Winning with the King’s Gambit, Joe Gallagher (Batsford 1992)

Encyclopaedia of Chess Openings (ECO), 2nd edition (Chess Informator 1981)

King’s Gambit, Korchnoi and Zak (Batsford 1986)

Play the King’s Gambit, Estrin and Glaskov (Pergamon 1982)

The Romantic King’s Gambit in Games and Analysis, Santasiere and Smith (Chess Digest 1992)

Das angenommene Königsgambit, Bangiev (Schach-Profi-Verlag 1996)

Developments in the King’s Gambit 1980-88, Bangiev (Quadrant Marketing Ltd, London 1989)

Modern Chess Openings Encyclopaedia, edited by Kalinichenko (Andreyevski Flag, Moscow 1994)

The Gambit, M.Yudovich (Planeta Publishers, Moscow 1989)

Periodicals

Informator

New In Chess Yearbook

British Chess Magazine (BCM)

Chess Monthly

Magazine Articles

The King’s Bishop Gambit, Stephen Berry, Chess Monthly, November/December 1981

Play the King’s Bishop Gambit!, Tim Wall, British Chess Magazine, May 1997

Video

An Aggressive Repertoire for White in the King’s Gambit, Andrew Martin, Grandmaster Video 1995

INTRODUCTION

In the 19th century the art of defence was little understood. Hence, enterprising but unsound gambits often enjoyed great success. In those halcyon days for the King’s Gambit, boldness and attacking flair were more important than rigorous analytical exactitude. The King’s Gambit proved the perfect weapon for the romantic player: White would push aside the black e-pawn with 2 f4! and then overrun the centre, aiming to launch a rapid attack and slay the black pieces in their beds.

Nowadays, after a century of improvements in technique and the accumulation of theory by trial and error, things are somewhat different. Black players have learnt how to defend and any impetuous lunge by the white pieces will be beaten off with terrible losses to the attacker.

Even in the King’s Gambit, therefore, White is no longer trying to attack at all costs. He has had to adapt his approach and look for moves with a solid positional foundation, just as he does in other openings. As often as not, his strategy consists of stifling Black’s activity and then winning in an endgame thanks to his superior pawn structure. Here is an example of this in action.

This position is taken from the game Illescas-Nunn, which is given in the notes to Game 45 in Chapter 7. White has the better pawn structure (four against two on the queenside) and any endgame should be very good for him. On the other hand, Black has dynamic middlegame chances, as all his pieces are very active. White found a way to force an endgame here with 13 ♕e1! ♖e8 14 ♕h4! ♕xh4 (more or less forced) 15 ♘xh4. There followed 15...♘e3 16 ♗xe3 ♖xe3 17 ♖ae1 ♖xe1 18 ♖xe1 and White’s queenside pawns were much more valuable than Black’s ineffectual clump on the kingside. Furthermore, Black has not the slightest counterplay. It is no surprise that White won after another 22 moves.

There was no brilliant sacrificial attack in this game, yet White succeeded in defeating a top-class grandmaster. Here is another example, taken from Game 15 in Chapter 2.

Despite the fact that he is a pawn down, White’s chances would be no worse in an endgame. After all, he has control of the excellent f4-square and could aim to exploit the holes in the black kingside, which is looking disjointed. However, as Tartakower remarked ‘before the endgame the gods have placed the middlegame’. White is behind in development and in the game Black exploited this to launch an attack on the white king after 10♘d2 ♖e8 11 ♘xe4 ♖xe4+ 12 ♔f2 c5! etc., when White was soon overwhelmed.

This conflict between Black’s activity and White’s better structure is central to the modern approach to the King’s Gambit.

This position was reached in Short-Shirov, Madrid 1997, after White’s ninth move (see Chapter 2, Game 8). White has established the ideal pawn centre, while Black has doubled f-pawns. Therefore, statically speaking, White is better. However, Shirov has correctly judged that his active pieces are more important than White’s superior pawn structure. Black has a lead in development and can use this to demolish the white centre. The game continued 9...♕e7! 10 ♘c3 ♗d7 11 ♗f3 0-0-0 12 a3?! ♘xe4! and White’s proud centre was ruined, as 13 ♗xe4 f5 regains the piece with advantage. Shirov quickly followed up this positional breakthrough with a decisive attack. The time factor was of crucial importance here: in the ‘arms race’ to bring up the reserves White lagged too far behind.

So what is Black’s best defence to the King’s Gambit? Three general approaches are possible:

a) take the pawn and hold on to it, at least temporarily, with...g7-g5.

b) play...d7-d5 to counterattack.

c) decline the pawn in quiet fashion.

Of these options, the last one is the least promising. White shouldn’t be allowed to carry out such a key strategical advance as f2-f4 without encountering some form of resistance. Black normally ends up in a slightly inferior, though solid, position. Nevertheless, undemonstrative responses remain popular, mainly for practical reasons: there is less theory to learn than in the main line.

Option b) is under a cloud at the moment. Although defences based on ...d7-d5 allow Black free and rapid development of his pieces, often his inferior pawn structure comes to haunt him later in the game.

That leaves option a), 2...exf4. This is undoubtedly the most challenging move after which play becomes highly complex. As will be seen in Chapters 1 and 2, White has no clear theoretical route to an advantage after 2...exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 or 3...g5, while the variations in Chapter 3 have a poor standing for White. Black should therefore bravely snatch the f-pawn.

However, one should not forget the Bishop’s Gambit 3 ♗c4. Fischer favoured this move and at the time of writing it has been successfully adopted by Short and Ivanchuk (see Chapter 6). Furthermore, when I told David Bronstein I was writing a book on the King’s Gambit, he replied ‘You want to play the King’s Gambit? Well, Black can draw after 3 ♘f3. Play 3 ♗c4 if you want to win!’ However, as a word of warning we should remember the words of a great World Champion who grew up in the glorious age of the King’s Gambit: ‘By what right does White, in an absolutely even position, such as after move one, when both sides have advanced 1 e4, sacrifice a pawn, whose recapture is quite uncertain, and open up his kingside to attack? And then follow up this policy by leaving the check of the black queen open? None whatever!’ Emanuel Lasker, Common Sense In Chess, 1896. A hundred years on, the jury is still out!

Neil McDonaldFebruary 1998

CHAPTER ONE

Fischer Defence (3 ♘f3 d6)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6

‘This loss (against Spassky at Mar Del Plata 1960) spurred me to look for a “refutation” of the King’s Gambit... the right move is 3...d6!’ – Bobby Fischer, My Sixty Memorable Games.

It is ironic that Fischer, who hardly ever played 1...e5 as Black and only adopted the King’s Gambit in a handful of games (always with 3 ♗c4), should have discovered one of Black’s most effective defences. Or perhaps we should say rediscovered, as 3...d6 was advocated by Stamma way back in 1745, but subsequently ignored. This neglect is puzzling. Why wasn’t the strength of 3...d6 appreciated in the heyday of the King’s Gambit by Anderssen, Morphy and others? We can either conclude that even in the field of ‘romantic’ chess modern players are way ahead of the old masters, or point to the creativity of a genius able to find new ideas in familiar settings. After all, who would look for an improvement on move three of any opening?

The idea behind 3...d6 is simple. In essence, Black wants a Kieseritzky Gambit (Chapter 2) without allowing White to play ♘e5. If after 4 d4 g5 White plays 5 ♗c4, Black can enter the Hanstein Gambit with 5...♗g7 (or the Philidor after a subsequent 6 h4 h6). The Hanstein seems favourable for Black since he has a very solid kingside pawn structure. It is better for White to strike at the black pawn structure immediately with 5 h4!, as he also does in the Kieseritzky. Although after 5...g4 6 ♘g1, White’s knight has been forced to undevelop itself, Black has had to disrupt his kingside structure with...g5-g4. The strange looking position after 6 ♘g1 is the subject of Games 1-4, while 6 ♘g5 is seen in Game 5.

Instead of 4 d4, White can try 4 ♗c4, when Black responds 4...h6, hoping for 5 d4 g5 etc., when he reaches the favourable Hanstein. However, White can try to cross Black’s plans with either 5 d3 (Game 6) or 5 h4 (Game 7).

Game 1

Short-Akopian

Madrid 1997

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 d4 g5 5h4!

The best move. White undermines the black pawn structure before Black has the chance of solidifying it with ...h7-h6 and...♗g7. The resulting position may or may not be good for White, but one thing is clear: if he delays even a move, e.g. with 5 ♗c4, then Black will definitely have good chances after 5...♗g7 6 h4 h6 etc. (see Chapter 3, Games 19 and 20).

5...g4 6 ♘g1

The Allgaier-related 6 ♘g5?! is examined in Game 5.

6...♗h6

If Black’s last move was forced, here he is spoilt for choice. Alternatives include 6...♕f6 (Game 3, which may transpose to the present game) and 6...f5 (Game 4). Two other moves should also be mentioned:

a) 6...f3. This was popular once, but perhaps Black has been frightened off by the move 7 ♗g5! This is one of the many new ideas that Gallagher pioneered and then publicised in his Winning with the King’s Gambit. After 7...♗e7 8 ♕d2 h6 (8...f6 9 ♗h6! ♘xh6 10 ♕xh6 was good for White in Gallagher-Bode, Bad Wörishofen 1991) 9 ♗xe7 fxg2 (Black has to interpose this move as 9...♘xe7 10 gxf3 is bad for him) 10 ♗xg2 ♘xe7 11 ♘c3 ♘g6 12 ♕f2 White had good compensation for the pawn in Gallagher-Ziatdinov, Lenk 1991. We have the typical disjointed black kingside to contrast with White’s solid centre.

b) 6...♘f6. Instead of defending the f4-pawn, Black counterattacks against the e4-pawn. After 7 ♗xf4 ♘xe4 8 ♗d3 d5 (Black tried to make do without pawn moves in Hebden-Borm, Orange 1987, but was in deep trouble after 8...♕e7 9 ♘e2 ♗g7 10 0-0 0-0 11 ♗xe4! ♕xe4 12 ♘bc3 ♕c6 13 ♕d2 d5 [now he has to move a pawn to prevent 14 ♗h6] 14 ♘g3 etc. Another way to bolster the knight is 8...f5, but White had a good endgame after 9 ♘e2 ♗g7 10 ♗xe4 fxe4 11 ♗g5 ♗f6 12 ♘bc3 ♗xg5 13 hxg5 ♕xg5 14 ♘xe4 ♕e3 15 ♘f6+ ♔d8 16 ♕d2 ♕xd2+ 17 ♔xd2 ♘c6 18 ♖af1 ♘e7 19 ♖xh7 etc. in Hebden-Psakhis, Moscow 1986) 9 ♗xe4 dxe4 10 ♘c3 ♗g7 11 ♘ge2 0-0 12 ♕d2 f5 13 0-0-0 ♘c6 14 h5 a6, Yakovich-Zuhovitsky, Rostov 1988, and now Bangiev thinks that White is better after 15 h6.

7 ♘c3 c6

Here three other moves are possible:

a) 7...♘f6 aims to start an immediate attack on White’s centre after 8 ♘ge2 d5!? Then the game Christoffel-Morgado, Correspondence 1995, continued 9 e5?! ♘h5 10 g3 ♘c6 11 ♗g2 ♘e7 12 ♗xf4 ♗xf4 13 ♘xf4 ♘xf4 14 gxf4 c6 15 ♕e2 h5 and Black had a small advantage in view of his control of the important f5-square. Gallagher suggests that White’s play can be improved with the more dynamic 9 ♗xf4!? ♗xf4 10 ♘xf4 dxe4 11 ♗c4!, looking for an attack down the weakened f-file. After 11...♘c6! (Black must attack d4, not just to win a pawn but also to exchange queens) 12 0-0 ♕xd4+ 13 ♕xd4 ♘xd4 14 ♘fd5 ♘xd5 15 ♘xd5 ♘e6 16 ♘f6+ ♔e7 17 ♖ae1 Gallagher concludes that White has more than enough for his pawns. Indeed, he should regain them both over the next couple of moves whilst retaining a positional advantage.

b) 7...♘c6 is Black’s second option. Now 8 ♗b5 a6 9 ♗xc6+ bxc6 10 ♕d3 ♕f6 11 ♗d2 ♘e7 12 0-0-0 was unclear in Bangiev-Pashaian, Correspondence 1987. The critical move is 8 ♘ge2, which leads to the sharp variation 8... f3 9 ♘f4 f2+! 10 ♔xf2 g3+ 11 ♔xg3 ♘f6. Black has sacrificed his f- and g-pawns to expose the white king in similar fashion to the 5...d6 variation of the Kieseritzky (see Chapter 2, Games 8-10). This position has been analysed extensively by Gallagher, whose main line runs 12 ♗e2 ♖g8+ 13 ♔f2 ♘g4+ 14 ♗xg4 ♗xg4 15 ♕d3 ♗g7 16 ♗e3 ♕d7 17 ♘cd5 0-0-0 18 b4 ♖de8 19 b5 ♘d8 20 c4 ♘e6, and now 21 c5 dxc5 22 dxc5 ♗xa1 23 ♖xa1 ♘xf4 24 ♗xf4 gives White compensation for the exchange.

c) 7...♗e6 was tried in Gallagher-Hübner, Biel 1991. Now instead of 8 ♕d3 a6! 9 ♗d2 ♘c6, which looked good for Black in the game, Gallagher suggests 8 ♘ge2, when 8...♕f6 9 g3 fxg3 10 ♘xg3 ♗xc1 11 ♖xc1 ♕f4 is not too different from the position reached in Games 1 and 2.

8 ♘ge2 ♕f6 9 g3 fxg3 10 ♘xg3 ♗xc1 11 ♖xc1 ♕h6?

After this White achieves easy development. The correct 11...♕f4, which prevents White’s smooth buildup by attacking the knight on g3, is examined in the next game.

12 ♗d3! ♕e3+ 13 ♘ce2 ♘e7 14 ♕d2!

This game demonstrates that the King’s Gambit often offers White good endgame chances, even when he is a pawn down.

14...♕xd2+ 15♔xd2 d5?

It is never a good idea to open the centre when you are underdeveloped. White now regains his pawn while maintaining his positional advantages. It was better to dig in with 15...♗e6, e.g. 16 c4 ♘a6 or 16...c5.

16 ♖ce1 ♗e6

If 16...dxe4 17 ♘xe4 the threat of 18 ♘d6+ is very disruptive.

17♘f4 0-0

Giving back the pawn, as 17...dxe4 18 ♖xe4 leads to disaster on the e-file.

18 exd5 ♘xd5 19 ♘xe6 fxe6 20 ♖xe6

White regains his pawn with excellent chances. He has more space in the centre, a lead in development and the opportunity to attack the sickly black g-pawn, which, although passed, is well blockaded and difficult to support.

20...♘d7 21 ♘f5

It was even better to play 21 ♗f5 according to Short, when after 21...♘7f6 22 c4 ♘b6 23 ♔d3 White is in complete control.

21...♔h8 22 ♖f1 ♖ae8 23 ♖xe8 ♖xe8 24 c4 ♘5f6 25 ♘g3 c5

A typical King’s Gambit situation has arisen. The black kingside pawns are inert, while the white centre is mobile and strong. Therefore Akopian concedes a protected passed pawn, hoping to entice the knight from the excellent blockade square on g3 and so activate the g-pawn. The alternative was to wait passively while White increased his space advantage with b2-b4 etc.

26 d5 ♔g7 27 ♘f5+ ♔h8 28 ♘d6 ♖f8 29 ♖e1 g3 30 ♗f5 ♘b6 31 b3 ♘e8 32 ♘xb7 ♘g7 33 ♗h3 ♖f4 34 ♘xc5 ♖xh4 35 ♗g2 ♖h2 36 ♖e2 ♘f5 37 ♗e4 ♘d6 38 ♗f3 ♖h6 39 ♘e6 ♖f6 40 ♗g2 ♘d7 41 c5 ♘f7 42 d6 ♘fe5 43 ♗d5 ♖f5 44 c6 ♘b6 45 ♗g2 ♖f2 46 ♖xf2 gxf2 47 ♔e2 1-0

Game 2

Fedorov-Pinter

Pula 1997

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 d4 g5 5 h4 g4 6 ♘g1 ♗h6 7 ♘c3 c6 8 ♘ge2 ♕f6 9 g3 fxg3 10 ♘xg3 ♗xc1 11 ♖xc1 ♕f4!

An attempt to disrupt the build up of White’s position. The attack on the knight means that White has no time for ♗d3 as played in the game above.

12♘ce2♕e3 13 c4?!

White finds an ingenious way to expel the queen. Nevertheless, the endgame with 13 ♕d2 ♕xd2+ 14 ♔xd2 seems a better approach.

13...♘e7 14♖c3 ♕h6 15 ♗g2

White could still have played for an endgame with 15 ♕d2. However, 15...♕xd2+ 16 ♔xd2 c5! 17 ♗g2 ♘bc6 looks better for Black. Why is this endgame worse for White than in Short-Akopian above? The point is that White has played c2-c4 here, which means that Black’s counterblow ...c6-c5! cannot be met with c2-c3, maintaining control of the central dark squares. The white centre is thus split after the inevitable d4xc5 and the e5-square becomes a strong outpost for a black knight. White is correct to seek a middlegame attack in the game.

15...0-0

Here 15...c5 is the natural positional move, undermining White’s centre. But the crucial question is: can White overwhelm his opponent before he can develop his pieces? It seems that the answer is yes after 16 ♖d3! ♘bc6 17 dxc5 dxc5 18 ♖d6. For example, 18...♗e6 (18...♕e3 19 ♘f1! wins the queen, while 18...♕g7 19 ♘h5 ♕xb2 20 ♘f6+ ♔f8 21 0-0 gives White a big attack) 19 ♘f5! ♕f6 20 ♖xe6! fxe6 21 ♘d6+ ♔d7 22 e5! ♕g6 23 ♘f4 ♕g8 24 ♘xb7+ ♔c8 25 ♘xc5 ♕d8 26 ♕d6 with a very strong attack.

16 0-0 ♘g6?

Here 16...c5! was the most challenging move. As far as I can see Black then has good chances, e.g. 17 dxc5 dxc5 18 ♖d3 ♘bc6 19 ♖d6 ♕xh4!? Of course, the position remains very complicated and there could be a knockout blow concealed among the thickets of variations.

17♖f6

Now, in view of the threat h4-h5, White wins the important d6-pawn, after which he can always claim positional compensation for the pawn deficit.

17...♕xh4 18 ♖xd6 c5

Too late!

19 ♘f5 ♕g5 20 ♖d5

After 20 ♖g3!?, 20...h5 looks okay for Black, but not 20...♘c6 21 ♖xg4! nor 20...♗xf5? 21 exf5 ♕xf5 22 ♗xb7 ♘d7 23 ♖d5! ♕e6 24 ♗xa8 ♖xa8 25 ♘f4!! ♘xf4? 26 ♕xg4+ and White will be the exchange up in the endgame.

20...cxd4 21 ♖g3 ♕f6 22 ♖xg4 ♗f3 23 ♘f4 ♗xd5 24 ♘xd5 ♕e5 25 ♖g5 ♔h8 26 ♖h5 ♘d7

There was a draw by repetition after 26...♖e8 27 ♘fe7 ♕g7 28 ♘f5 ♕e5.

27 ♕f3

A last winning try. White could have forced a draw with 27 ♖xh7+ ♔xh7 28 ♕h5+ ♔g8 29 ♘h6+ ♔h7 30 ♘f5+ ♔g8 31 ♘h6+.

27...♖fe8 28 ♘h6 ♕g7 29 ♘xf7+ ♔g8 30 ♘h6+ ♔h8 31 ♘f7+ ½-½

White has to force the draw in view of the material situation.

Game 3

Gallagher-G.Flear

Lenk 1992

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 d4 g5 5 h4 g4 6 ♘g1 ♕f6 7 ♘c3 ♘e7

After 7...c6 8 ♘ge2 ♗h6 play will transpose to the two games above. Gallagher points out that the attempt to refute 7...c6 with 8 e5 falters after 8...dxe5 9 ♘e4 ♕e7 10 dxe5 ♕xe5 11 ♕e2 ♗e7 12 ♗d2 ♘f6! Meanwhile, Bangiev recommends 7...c6 8 ♘ge2 ♘h6, but this is either a brainstorm or a misprint.

8 ♘ge2 ♗h6 9 ♕d2!?

Note this idea only works after ...♘e7. If you put the knight back on g8 and play...c7-c6 instead, then 9 ♕d2?? loses a piece after 9...f3.

Gallagher actually prefers 9 ♕d3 here. Play could go 9...a6 (to play ...♘bc6 without allowing ♘b5) 10 ♗d2 ♘bc6 11 0-0-0 ♗d7 when a critical position is reached:

This idea received a practical test in the game Russell-Beaton, Scotland 1994 (through a different move order beginning 8 ♕d3!?). Unfortunately, White blundered immediately with 12 ♘d5?, when he had nothing for his pawn after 12...♘xd5 13 exd5 ♘e7 14 ♘c3 0-0-0 etc. The key variation is the calm 12 ♔b1 0-0-0 13 ♗c1, when John Shaw gives 13...f3 as unclear, while 13...♖he8 14 g3 f3 15 ♘f4 is Bangiev’s choice. But doesn’t Black have an excellent position after, say, 15...♕h8 and 16...f5 here?

9...♘bc6 10♘b5!

The only way to exploit the queen’s absence from d8 is to attack c7. After 10 g3 ♗g7! 11 d5 fxg3! 12 ♘xg3 (White cannot allow 12...♕f2+ and 13...g2) 12...♘d4 13 ♗g2 ♘f3+ 14 ♗xf3 ♕xf3 15 ♘ce2 ♗e5 Black was winning in Bangiev-Figer, Correspondence 1987.

10...♔d8 11 d5

This looks horribly anti-positional, as it gives up the e5-square to the black knight. Bangiev recommends 11 e5!, which leads to a highly contentious position after 11...♕f5 12 exd6 ♘d5 13 dxc7+ ♔d7.

The Russian Master claims that White is better in the complications. However, according to Gallagher ‘Bangiev didn’t suggest a way to beat off the black attack. I can’t see anything resembling a White advantage.’ Who is right? In a book published after Gallagher’s comments, Bangiev comes up with the goods: 14 ♘g3!? Somewhat surprisingly, this seems good for White! For example:

a) 14...♕e6+ 15 ♗e2 ♖e8 (15...♘e3 16 d5! ♕xd5 17 ♕xd5+ ♘xd5 18 ♗xg4+) 16 0-0 fxg3 17 ♕xh6 ♕xh6 18 ♗xg4+ ♕e6 19 ♖xf7+ ♖e7 20 ♗xe6+ ♔xe6 21 ♖xe7+ ♘dxe7 22 ♗g5 ♔d7 23 ♖e1 when White has three pawns for the piece and a dangerous initiative since the black queenside is buried.

b) 14...♖e8+ 15 ♔d1 ♕e6 (15...♘e3+ 16 ♕xe3!) 16 ♗d3 ♘e3+ 17 ♕xe3! fxe3 18 ♗f5 e2+ 19 ♔e1 ♗xc1 20 ♖xc1 a6 21 ♗xe6+ fxe6 22 ♘c3 ♘xd4 23 ♘cxe2 ♘xe2 24 ♔xe2 ♔xc7. Here the weak black pawns on e6 and g4 give White a positional advantage (analysis by Bangiev).

Judging from this, 11 e5 seems to be a much better try than 11 d5.

11...♘e5 12♘xf4

In a later game Gallagher improved with 12 ♕c3 c6 (forced) 13 dxc6 ♘7xc6 14 ♗d2.

see following diagram

Black now tried 14...f3 and was soon overwhelmed: 15 0-0-0! fxe2 16 ♗xe2 ♔e7 (if 16...a6 17 ♖hf1 ♕e6 18 ♘xd6 and White has an enduring attack for his piece; maybe 16...♗d7 is best) 17 ♖hf1 ♕g6 18 h5! ♕xh5 (if 18...♕e6 19 ♘c7 ♕xa2 20 ♗xh6 and Black’s king faces an attack from all White’s pieces) 19 ♖h1 ♗xd2+ 20 ♕xd2 ♕g6 21 ♖h6! ♖d8 22 ♖xg6 hxg6 23 ♘c7 ♗e6 24 ♘xa8 ♖xa8 25 ♕xd6+ ♔e8 26 ♗b5 ♖c8 27 ♕xe5 1-0 Gallagher-Fontaine, Bern Open 1994.

This seems very convincing, but 14...a6!? would have been a much tougher defence. Then Black would win after 15 ♘xd6 ♕xd6 16 0-0-0 ♗d7 17 ♗xf4 ♗xf4+ 18 ♘xf4 ♕b4 etc., so White has to try 15 ♘bd4. With the knight chased from b5, 15...f3! is now safe, e.g. 16 ♗xh6 (after 16 0-0-0 fxe2 17 ♗xe2 ♗d7 White has little to show for his piece ) 16...f2+ 17 ♔d1 ♕xh6 and Black is much better.

12...a6 13♘d4 g3!

White has regained his pawn but is in serious trouble due to the pin on f4. Flear’s excellent move prevents White from supporting the pinned knight with g2-g3.

14 ♘de2 ♖g8 15 ♕d4 ♗g4 16 ♗e3 ♗xe2 17 ♘xe2 ♘f3+! 18 gxf3 ♕xf3 19 ♗xh6 ♕xh1 20 ♗g5 g2 21 ♔f2 ♖xg5

Instead of giving back the exchange, the computer program Fritz prefers to win another one with 21...h6. Now a bishop retreat from g5 allows 22...g1♕ with a winning attack, so 22 ♗xg2 (22 ♗f6 ♕h2! 23 ♔e3 ♖g3+ 24 ♔d2 g1♕ wins) 22...♕xa1 23 ♗f6 ♕xa2 24 e5 ♕a5 and the white attack will fail, with huge losses.

22 hxg5 gxf1♕+ 23 ♖xf1 ♕h4+ 24 ♘g3 ♔d7 25 ♕f6 ♖g8 26 ♖h1 ♕xg5 27 ♕xg5 ♖xg5 28 ♖xh7 ♔e8 ½-½

White seems to be a little better here after 29 ♘h5.

Game 4

Hector-Leko

Copenhagen 1995

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 d4 g5 5 h4 g4 6 ♘g1 f5

An imaginative idea. White hasn’t yet got any pieces in play, so Black feels that he has time to strike at his opponent’s centre and dispose of the strong e-pawn. It looks risky to remove the remaining pawn cover from Black’s king, but hasn’t White done the same thing with 2 f4? Furthermore, White’s play is hardly above criticism. In the first six moves he has developed and then undeveloped his knight, and moved his rook’s pawn two squares. This hardly accords with the precepts of classical chess, which require rapid and harmonious development of the pieces.

7 ♘c3

Here 7 ♗xf4 fxe4 8 ♘c3 ♘f6 transposes to the main game.

An important tactical point is the fact that 7 exf5? fails to 7..♕e7+. For example, 8 ♗e2 ♗xf5 9 ♘c3 (if 9 ♗xf4 ♕e4!) 9...♗h6 10 ♘d5 ♕e4 11 ♘xc7+ ♔d7 and Black wins (Raetsky). Or if 8 ♕e2 ♗xf5 9 ♗xf4 ♗xc2! and White has hardly any compensation for the pawn. It is a pity that 8 ♘e2 doesn’t seem to work after 8...f3, e.g. 9 ♗g5 fxe2 10 ♗xe2 ♘f6 11 0-0 ♗g7 12 ♗b5+ ♔d8! or 9 gxf3 gxf3 10 ♖h3 fxe2 11 ♗xe2 ♗h6!? In neither case does White have enough play for a piece.

7...♘f6 8 ♗xf4

The critical move. In Shevchenko-Raetsky, Russia 1992, White played the careless 8 ♕e2? and after 8...♗h6 9 exf5+ ♔f7! Black suddenly had an overwhelming lead in development. White was swept away in impressive style: 10 ♕f2 ♖e8+ 11 ♔d1 g3 12 ♕f3 ♗xf5 13 ♗c4+ ♔g7 14 ♘ge2 ♗g4 15 ♕xb7 d5! 16 ♗d3 (if 16 ♕xa8 dxc4 17 ♕xa7 ♘c6 followed by 18...♘xd4 crashes through) 16...♘e4! (completing the strategy began with 6...f5; Black has absolute control of e4) 17 ♕xa8 (if 17 ♗xe4 dxe4 18 ♕xa8 ♕xd4+ 19 ♗d2 f3! – Raetsky) 17...♘f2+ 18 ♔e1 ♘xh119 ♕xd5 ♕xh4 20 ♗c4 ♔h8 21 ♕f7 ♗h5 22 ♕xc7 ♘f2 23 ♔f1 ♕h1+ 24 ♘g1 ♘g4 0-1, as 25 ♘ce2 ♘h2+ 26 ♔e1 ♕xg1+ is more than flesh can stand. White played the whole game without his queen’s rook or bishop.

8...fxe4 9 ♕d2

White has also tried 9 ♕e2 d5 10 ♗e5, when Bangiev recommends 10...c6! 11 ♘d1 ♘bd7 12 ♘e3 ♘xe5 13 dxe5 ♘d7 14 ♕xg4 ♕a5+ 15 c3 ♘xe5 16 ♕h5+ ♘f7 as clearly good for Black.

At the time of writing, theory has yet to decide on the strongest response to 7...f5. Nevertheless, I would suggest that 9 d5 ought to be considered. I like the idea of preventing Black consolidating his centre with 9...d5. In his annotations to the Hector game, Leko gives 9 d5 a question mark, claiming that Black is a little better after 9...♗g7 10 h5 0-0 11 h6 ♗h8 12 ♕d2 ♕e8. However, instead of pushing the f-pawn White can mobilise his pieces, e.g. 9...♗g7 10 ♕d2 0-0 11 ♘ge2, planning moves like 0-0-0, ♘d4 and ♗c4.

9...d5 10 ♗e5?!

White’s position begins to fall apart after this. According to Leko, White should have played 10 ♘b5 ♘a6 11 ♘c3 c6 12 ♗xa6 bxa6 13 ♘ge2 with unclear play. However, since Black can force a draw by repetition with 11...♘b8, this recommendation is hardly inspiring. White doesn’t play the King’s Gambit to agree a draw after 11 or 12 moves!

10...c6 11 ♘ge2 ♗e6 12 ♘f4

If 12 ♕g5 ♘bd7 13 ♘f4 ♕e7! 14 ♘h5 ♘xh5! 15 ♗xh8 ♘g3 16 ♖g1 ♕xg5 17 hxg5 ♗e7 gives Black excellent play for the exchange – Leko.

12...♗f7 13 ♘d1 ♘bd7 14 ♘e3 ♘xe5 15 dxe5 ♕c7!

This simple move refutes White’s attack by pinning the e-pawn and preparing...0-0-0. Since the e-pawn is fatally weak, White will soon be two pawns down without any real compensation.

16 ♕c3 0-0-0 17 0-0-0 ♘h5 18 ♘e2 ♗h6 19 ♔b1 ♗xe3 20 ♕xe3 ♔b8 21 ♕g5 ♖hg8 22 ♕f5 ♗g6 23 ♕g5 ♖de8 24 ♕xg4 ♕xe5 25 ♕g5 ♕xg5 26 hxg5 ♖e5 27 g4 ♘g7 28 ♘f4 ♘e6 0-1

Game 5

Morozevich-Kasparov

Paris (rapidplay) 1995

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 d4 g5 5 h4 g4 6 ♘g5

White plays in enterprising style, hoping to bamboozle the World Champion with a rarely seen sacrificial line. Since this was a rapidplay game, such an approach makes some sense.

6...h6

An interesting moment. According to Fischer it is better to play 6...f6!, when 7 ♘h3 gxh3 8 ♕h5+ ♔d7 9 ♗xf4 ♕e8! 10 ♕f3 ♔d8 leaves White with little for the piece. Another possibility given by ECO is 7 ♗xf4 fxg5 8 ♗xg5 ♗e7 9 ♕d2 ♗e6! 10 ♘c3 ♘d7 and again Black should be able to defend successfully. This opinion is supported by Gallagher. Why did Kasparov avoid 6...f6 then? Perhaps he was afraid of an improvement or perhaps he had simply forgotten the theoretical refutation.

7 ♘xf7 ♔xf7 8 ♗xf4 ♗g7 9 ♗c4+ ♔e8

White now has a favourable version of the Allgaier Gambit, since normally after 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 ♘g5 h6 6 ♘xf7 ♔xf7 7 ♗c4+ Black responds 7...d5! (or if 7 d4, then 7...f3! 8 ♗c4+ d5). The point is that Black usually gives up the d-pawn to speed up his development. In the game Black has already played...d7-d6, so he would be a tempo down if he were to revert to...d6-d5 after ♗c4+.

It is also worth comparing the sacrifice here with the line 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 ♘e5 d6 6 ♘xf7?, as played in Schlechter-Maroczy, Vienna 1903. (This is real coffee-house chess. I have a book on Schlechter that is full of fine positional games. Yet in those days nobody was immune from the outlandish sacrifices which seem ridiculous to modern eyes.) After 6...♔xf7 7 ♗c4+ ♔e8 Black was clearly better. In the Kasparov game we have reached a similar position with the moves d2-d4 and...h7-h6 thrown in. This should help White. Or does it? The move...h7-h6 prevents ♗g5 in some lines and, as we shall see, h7 proves a good square for the black rook...

10 0-0??

Very stereotyped. The white king will prove to be a target on the kingside. It was better to play 10 ♘c3, intending 11 ♕d2, 12 0-0-0 etc. (if...♘c6 then ♗e3) with an enduring initiative which would have offered fair chances in a rapid game. If this plan fails then the whole variation is simply bad for White.

10...♘c6 11 ♗e3

White might as well play 11 c3, as the coming incursion on the f-file leads nowhere.

11...♕xh4!

A good defensive move, vacating d8 for the king, and a strong attacking move, threatening 12...g3.

12♖f7 ♖h7!

Another dual-purpose move. Black defends the bishop and threatens 13...♗xd4! 14 ♖xh7? ♗xe3+ and mate on f2.

13 e5 ♘a5

This beats off the attack with frightful losses. It is no wonder that the attack fails: not only has White sacrificed a piece, but the queenside rook and knight may as well be any place but on the board.

14 ♗d3 ♔xf7 15 ♕f1+ ♔e7 16 ♗xh7 ♗e6 17 ♘d2 ♖f8 18 exd6+ cxd6 19 ♕e2 ♔d8 20 c3 ♘e7 21 ♖e1 ♗c4!

Of course capturing twice on c4 now leaves el en prise. The game move allows a mercifully quick finish.

22 ♗f2 ♖xf2 23 ♕xf2 g3 0-1

Mate on h2 or loss of the queen follows.

Game 6

Gallagher-Kuzmin

Biel 1995

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 ♗c4 h6 5 d3

This is Gallagher’s pet idea. White strengthens his centre and keeps d4 free for his king’s knight (this may sound bizarre but all is soon revealed!). After the alternative 5 d4, play could transpose to a Hanstein with 5...g5 etc. (see Chapter 3, Game 20). Since the Hanstein looks suspect for White, this is another reason to consider 5 d3. However, the analysis below also gives 5 d3 a thumbs down, so the conclusion seems to be that 4 ♗c4 is inaccurate: 4 d4 is the only decent try.

5...g5 6 g3 g4

Four other moves are possible:

a) 6...fxg3 7 hxg3 ♗g7 looks dangerous for Black after the sacrifice 8 ♘xg5 hxg5 9 ♖xh8 ♗xh8 10 ♕h5 ♕f6 11 ♘c3. However, White has still has to prove the win after, say, 11...♔f8!? 12 ♘d5 ♕e5!? or 12 ♗xg5 ♕g6!

b) 6...♗h3 was played in Gallagher-Lane, Hastings 1990, when 7 ♘d4?! d5! 8 exd5 ♗g7 led to obscure play. Gallagher suggests that 7 ♕d2 was better, preventing ...♗g2 and intending to capture on f4 (the immediate 7 gxf4 is less good, as 7...g4 8 ♘d4 ♕h4+ looks annoying; whereas after 7 ♕d2 Black’s check on h4 can be answered by ♕f2).

c) 6...♘c6 7 gxf4 g4 (if 7...♗g4 Gallagher suggests 8 c3, hoping for 8...gxf4 9 ♗xf4 ♘e5? 10 ♗xe5 and 11 ♗xf7+ winning) 8 ♘g1 ♕h4+ 9 ♔f1 f5! (much more dynamic than 9...♘f6 10 ♔g2 ♘h5 11 ♘c3 g3 12 ♕e1 ♖g8 13 h3 with advantage to White, as given by Gallagher; note that 12...♘xf4+ 13 ♗xf4 ♕xf4 14 ♘d5 is bad for Black, as is 13...♘xf4+ for the same reason)

see following diagram

10 ♘c3 ♘f6 11 ♔g2 fxe4 12 dxe4 ♗d7 13 h3? (following the plan outlined in the last bracket, but here it is inappropriate; 13 ♗e3, intending 14 ♕e1, looks better, when White may have the advantage) 13...♘h5! 14 hxg4 ♕g3+ 15 ♔f1 ♘xf4 16 ♕f3 (the queen exchange saves White from immediate collapse, but he has two weak pawns on e4 and g4 and a hole on e5, whereas Black only has one weakness on h6; nevertheless, he uses his slight lead in development to avoid the worst) 16...♕xf3+ 17 ♘xf3 ♘g6 18 g5 (liquidating one of his weak pawns) 18...6g4 19 ♗e2 0-0-0!? (on this move or the last Black could have played ...h6xg5, but Beliavsky chooses a dynamic pawn sacrifice) 20 gxh6 ♗e7 with unclear play which eventually led to a draw in Belotti-Beliavsky, Reggio Emilia 1995/96.

d) 6...♗g7 7 c3? ♘c6! (ruling out 8 ♘d4) 8 ♘a3 ♗e6 9 ♕b3 ♕d7 10 gxf4 ♗xc4 11 ♕xc4 (if 11 ♘xc4 d5!) 0-0-0 12 ♗d2 (McDonald-Morris, Douai 1992) and now Black should have played 12...♕h3! 13 ♖f1 d5! with a big advantage as 14 exd5? ♖e8+ 15 ♔f2 g4 wins for Black. Critical was 7 gxf4! g4 8 ♘g1 ♕h4+ 9 ♔f1 and we have option c) above but with the black bishop on g7 rather than the knight on c6. Perhaps Black should try 9...f5, as 9...♘f6 10 ♔g2 ♘h5 11 ♘c3 g3 12 ♕e1 ♖g8 13 h3 is good for White (if 13...♘xf4+ 14 ♗xf4 ♕xf4 15 ♘d5 etc.).

7 ♘d4 f3 8 c3

Gallagher suggests the alternative plan of 8 ♗e3, ♘c3, ♕d2 and 0-0-0 in his book.

8...♘c6!

This is Kuzmin’s improvement. Rather than prevent the white knight going to d4 with 6...♗g7 or 6...♘c6, Black attacks it when it reaches this square. Black has tried two other moves:

a) 8...♗g7?! (actually the move order was 7...♗g7 8 c3 f3) 9 ♕b3 ♕d7 (forced because if 9...♕e7 10 ♘f5! ♗xf5 11 ♕xb7 wins) 10 ♗f4 ♘c6 (too late) 11 ♘f5 ♗e5 12 ♘d2 and White had good play for the pawn in Gallagher-G.Flear, Paris 1990.

b) 8...♘d7!? is an improvement on Flear’s 8...♗g7, played by... his wife! The knight heads for e5, which is a more efficient way of defending f7 from attack by ♕b3 than 9...♕d7 in the previous variation. The game McDonald-C.Flear, Hastings 1995, continued 9 ♘a3 ♘e5 10 ♗f4 ♘xc4 11 ♘xc4 ♘e7! (and now the other knight heads for e5!) 12 ♕a4+ ♗d7 13 ♕b3 ♘g6 14 ♗e3 ♘e5 15 0-0-0 ♖b8? (too passive; 15...♗g7 is fine for Black) 16 ♘xe5 dxe5 17 ♘f5! (now White has good chances) 17...♗xf5?? 18 ♕b5+! (a deadly zwischenzug) 18...♕d7 19 ♕xe5+ ♗e6 20 ♕xh8 h5 21 ♗c5 and Black resigned. Despite the unfortunate outcome, Black’s opening idea seems good.

9 ♘a3?!

Here 9 ♘xc6 bxc6 would be positional capitulation, so White should try 9 ♕a4, when Kuzmin analyses 9...♗d7 10 ♕b3 ♘e5 11 ♕xb7 ♘xc4 12 dxc4 ♗g7 as slightly better for Black.

9...♘xd4 10 cxd4 ♗g7

White’s centre is dislocated and will inevitably crumble. Therefore, Gallagher goes for a do or die attack.

11 ♕b3 ♕e7 12 ♗f4 c6

Not 12...♗xd4? 13 ♗xf7+ ♕xf7 14 ♕a4+ ♗d7 15 ♕xd4 etc.

13♕b4

Playing for traps as 13 d5 ♘f6 14 dxc6 bxc6 is bad.

13...a5!

Kuzmin avoids the draw with 13...d5? 14 ♗d6 ♕g5 (14...♕e6?! is risky: 15 ♗xd5 cxd5 16 ♘b5 etc. ) 15 ♗f4 ♕e7 etc.

14♕b6

If 14 ♕xd6 ♕xd6 15 ♗xd6 b5 16 ♗b3 a4 17 ♗c2 ♗xd4 and wins (Kuzmin).

14...d5 15♗xd5

The only chance, as 15 ♗b3 ♖a6 16 ♕c7 ♕xc7 17 ♗xc7 ♗xd4 is hopeless.

15...♖a6!

The last difficult move. On the other hand, 15...cxd5? 16 ♘b5 would have given White a dangerous attack.

16 ♕b3 cxd5 17 ♘b5 ♕b4+

The exchange of queens kills off White’s initiative.

18 ♕xb4 axb4 19 ♘c7+ ♔d8 20 ♘xa6 bxa6

The dust has cleared and Black has a decisive material advantage.

21 e5 ♘e7 22 ♖c1 ♗e6 23 h3 gxh3 24 ♔f2 ♔d7 25 ♔xf3 ♘c6 26 g4 ♘xd4+ 27 ♔e3 ♘c6 28 d4 f6 29 exf6 ♗xf6 30 ♖xh3 ♗xg4 31 ♖xh6 ♗xd4+ 32 ♔d3 ♖xh6 33 ♗xh6 ♗xb2 34 ♖f1 ♗e6 35 ♗d2 a5 36 ♖h1 ♗f5+ 37 ♔e3 ♔d6 38 ♖h6+ ♔c5 0-1

Game 7

C.Chandler-Howard

Correspondence 1977

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 d6 4 ♗c4 h6

An interesting alternative idea here is 4...♗e7!?, as played in McDonald-Skembris, Cannes 1993. After 5 0-0 ♘f6 6 d3 d5 7 exd5 ♘xd5 8 ♗xd5 ♕xd5 9 ♗xf4 0-0 White had a minuscule advantage. In effect, Black has played a Cunningham Defence but avoided the normal problem after 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 ♘f3 ♗e7 4 ♗c4 ♘f6 of 5 e5!, chasing his knight from the centre. The drawback is that he is a tempo down on the line 5 d3 d5 6 exd5 ♘xd5 7 ♗xd5 ♕xd5 8 ♗xf4. However, 5 d3 is hardly an ultra-sharp move, so it seems that Black can afford this liberty.

5 h4

Attacking the ghost of the pawn on g5.

5...♘f6

Instead Black could go hunting for more pawns with 5...♗e7 6 ♘c3 (a more solid approach is 6 d4 ♗g4 7 ♗xf4 ♗xh4+ 8 g3) 6...♗g4 7 d4 ♗xh4+ 8 ♔f1 g5. However, according to an article in Chess Monthly, January 1976, 9 ♕d3 then gives White sufficient play, e.g. 9...♗xf3 (more or less forced, as 9...♗g3 10 ♘xg5 ♕xg5 11 ♕xg3 fxg3 12 ♗xg5 is best avoided) 10 ♕xf3. White has chances in view of his lead in development, his two bishops and the awkward position of the bishop on h4.

6 ♘c3 ♗g4

Another sharp possibility is 6...♗e7 7 d3 ♘h5 8 ♘e5 dxe5 9 ♕xh5 0-0 10 g3!?, planning to answer 10...fxg3 with 11 ♗xh6. However, the best move is probably 6...♘c6!, as played in McDonald-G.Flear, Hastings 1992/93.

see following diagram

After 7 d4 ♘h5 Black was ready to complete his development with ...♗e7, ...♗g4 and ...0-0, so White should do something fast.

The sacrifice 8 ♘e5 doesn’t look particularly brilliant after 8...dxe5 9 ♕xh5 g6 and 10...♘xd4. I also didn’t like the look of 8 ♘e2 ♕f6 or 8 ♘d5 ♘g3 9 ♖g1 g5 etc. Therefore, I tried the unusual looking move 8 d5!? ♘e7 9 ♘d4 ♘g3 10 ♖h2, when I was happily contemplating 11 ♗xf4 next move, or if 10...♘g6 then 11 h5 ♘e5 12 ♗b5+ followed by ♗xf4. However, Flear found a brilliant move which shows up all the weaknesses created by 8 d5: 10...g5!! 11 hxg5 ♘g6. Black has returned the extra pawn to keep hold of f4. 10...g5 has also cleared the diagonal a1-h8 for the dark-squared bishop, which White has weakened with d4-d5. The e5-square is now firmly in Black’s hands and is a central outpost for a black knight or bishop. The game continued 12 ♗b5+ ♗d7 13 ♗xd7+ ♕xd7 14 gxh6 ♗xh6 15 ♘f3 and now the simple 15...0-0-0, planning 16...♖de8 etc., attacking e4, is good for Black. The white king is a long way from the safety of the queenside. In the game Black tried the premature 15...f5, when 16 exf5 ♕xf5 17 ♕d3! was unclear.

7 d4 ♘h5 8 ♘e5!

Breaking the pin in some style. Of course 8...♗xd1 9 ♗xf7+ ♔e7 10 ♘d5 is mate.

8...dxe5 9 ♕xg4 ♘f6