Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

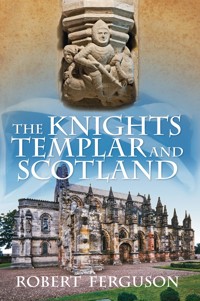

Places and books like Rosslyn Chapel and The Da Vinci Code have focused attention on Scotland's Knights Templar. Who they were and what they did has been touched upon, but never properly explored until now. They were close advisors to Scotland's early kings; they were major property owners and respected landlords in a harsh and unforgiving time; and they were secretive and arrogant. But did they really flee from France to Scotland just prior to their arrest in 1307? Did they fight with Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn in 1314? And how did the Templars continue on after Bannockburn? In The Knights Templar and Scotland Robert Ferguson intertwines Templar and Scottish history, from the foundation of the order in the early twelfth century right up to the present day. Including a comparison of the arrest of the Templars in France with the Templar Inquisition at Holyrood, and an examination of the part they played at Bannockburn, this is an essential book for anyone with an interest in the history of the Knights Templar.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Peggy, and to Shari and Tim

First published in 2010, 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Robert Ferguson, 2010, 2011

The right of Robert Ferguson, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6977 5

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6978 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

1 The Knights Templar of Jerusalem

2 Balantrodoch: The Life of the Templars

3 Templar Life, Rights and Privileges

4 The Excommunication of Robert the Bruce

5 The Templars’ Arrests

6 The Templars’ Flight to Scotland

7 Scotland’s Templar Inquisition

8 The Knights Templar and the Battle of Bannockburn

9 Rosslyn Chapel: A Templar Legacy?

10 The Templars after Bannockburn

11 The Modern Scottish Knights Templar

Appendix: Could there have been Templars at Bannockburn?

Bibliography

About the Author

Illustrations

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First I would like to thank the staff at the National Archives of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland. For an American who was foraging around looking for ancient documents and old books, their help was invaluable.

J. Connall Bell and Patricia Tennyson Bell are to be thanked for providing me with the motivation to begin writing this book. Along this line, special thanks go to John Flemming, a Scot whose opinion about the Templars being at Bannockburn was, and is, unequivocal.

In Scotland, special thanks go to Stuart Morris of Balgonie for providing a link between the past and the present. I cannot thank George Stewart enough for putting the current Scottish Templar Orders in perspective. Ron Sinclair and Bill Hunter provided me with their generous help in connecting me with sources of information about the current Templar community and about Alexander Deuchar. Also, thanks go to John Ritchie who provided me with an initial connection with the Milit Templi Scotia.

On the practical side, I would like to thank Victoria Kibler who proofed and edited my manuscript. Thanks also go to Jonathon Kibler-McCabe, who speaks fluent Gaelic, and to Bronwyn Jones who translated works originally in French that went back to the eighteenth century. The Appendix could not have been written without the help of Don Bentley, a Professor Emeritus, Pomona College, who specialises in statistics.

The help of Simon Hamlet of The History Press in guiding me through the initial process was invaluable, as was that of Robin Harries. Special thanks go to Abigail Wood, my editor, who converted the language of a lawyer and the format of a legal brief to a very readable book. And, finally, there is my wife Peggy, who put up with me when I was cloistered in the study, and who motivated me when I needed encouragement to continue.

PREFACE

At the bottom of the letterhead stationary for the Ordo Supremus Militaris Templi Hierosolymitani, Grand Priory of the Scots, is the phrase:

Scotland – The Unbroken Templar Link.

This book had its beginning when I asked the Grand Bailiff if that phrase was true, and where could I find the information to back it up? His answer was yes, the statement was true, but no, he did not know exactly where the information could be found. This prompted my naive reply, ‘I’ll find out’, thinking the answer was simple and that it could be the subject for an article in the Priory’s newsletter.

What started as a simple question turned into a major project that has required over three years of research and writing. It quickly became apparent that over the last hundred years, little has been written about the Knights Templar in Scotland. This was particularly true for the period from 1314, the year of the Battle of Bannockburn, to the early 1960s. During this period, there were various antidotal references and a lot of speculation, but I could find no easily referenced historical facts. This raised the question, if a substantial amount of effort is going to be required to answer my first question, why not write a book?

Another reason for this book is a statement from my good friend John Fleming, a Scot who now lives in southern California, but still returns to Scotland for a couple of months each summer. When I mentioned I was writing a book about the Templars and Scotland, he replied, ‘Oh, you mean at Bannockburn.’

I was surprised and asked, ‘What do you mean? Do you know about them?’

‘Of course,’ he answered. ‘Everybody does.’

‘But how?’ I asked. ‘Nothing has been written.’

‘It’s just passed down,’ he said. ‘Everyone knows the Templars were at Bannockburn. You hear about it.’

In line with John’s statement, I thought the best place to begin the quest was with the oft-asked question, were the Knights Templar present at the Battle of Bannockburn? But the Battle of Bannockburn happened two years after the formal dissolution of the Templars, and seven years after King Philip IV of France issued the warrants for their arrest on 13 October 1307. From this, it became clear that before Bannockburn could be analyzed, it was necessary to research the history of the Knights Templar in Scotland from the time of their arrival in 1127, until their arrest and dissolution. But an understanding of Scotland’s Templar history required a good general knowledge of who and what the Templars were. There were no Templar battles in Scotland. In Scotland the Templars were monks, recruiters, landlords and businessmen. So, in order to insure that all the readers have a basic knowledge of the Templars, the book begins by describing these aspects of Templar life, followed by their battles and activities in Palestine.

Most of what is written concerning the Knights Templar in Scotland consists of articles written in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I found that these tend to be anecdotal, concentrate on the detail of particular events, and do not provide a description that leads to an understanding of the lives of the medieval Knights Templar. After several readings of the available materials, it became apparent that the information about who and what the Templars were in Scotland revolved around their headquarters, Balantrodoch, and the management of their hundreds of properties that existed throughout Scotland.

Why did the Templars come to Scotland? The answer to this question lies, to a great extent, in the excommunication in 1304 of the Scottish king, Robert the Bruce. This event is significant not only in explaining the flight of the Knights Templar to Scotland, but in explaining their reasons for staying there. Clement V was Pope when the French King Philip IV ordered their arrest, and it was Clement V who formally dissolved the Knights Templar. As significant as this event is, there is little modern discussion of it. Most historians give it no more than a few sentences. While the reason for the excommunication may be well known, I could not find a consistent version of the events leading up to it. In Chapter 4 I outline a number of the various versions.

Until the Battle of Bannockburn, most of what occurred in Scotland is tied to what happened first in Europe. In order that the reader might understand the Templars’ flight to Scotland, I recount the events that led to the Templars’ arrest in Chapter 5.

There has been much speculation on the question of whether the Templars actually fled from France prior to their arrests, and whether they went to Scotland. While there is no direct evidence that they did, the circumstantial evidence is overwhelming. It begins with the recently disclosed fact that the Templars’ second in command, Hugh de Pairaud, knew of the coming arrests and told his brothers. Then, not only were the Templars safe in Scotland, but Scotland provided a place where they could continue living as both monks and warriors. I have divided this subject into two parts. Chapter 6 describes the Templars’ flight, and the Appendix analyzes whether a sufficient number of qualified Templars would have been available to assist Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn.

In France, the Templars were subject to trial by King Philip IV, and an inquisition by Pope Clement V. They were threatened with, and in some cases suffered, unspeakable torture. This applied to not only the knights, but also to the hundreds of sergeants and others involved with the Order. In Scotland there were arrests, and there was an inquisition, of sorts. But as I describe in Chapter 7, it primarily involved the Templars’ attitude and ended up being much ado about nothing.

Were the Templars present at the Battle of Bannockburn? Most Knights Templar who are Scots, or are of Scottish ancestry, believe, like my friend John Fleming, that without question the answer is ‘yes’. The belief for many is absolute. But is it historically provable? Is there any unequivocal, historical evidence to back up the belief? The answer is that there is little or none. But as to whether or not there is circumstantial evidence that is more than speculation, the answer is yes, there is. Chapter 8 describes the events leading up to the Battle of Bannockburn, and the probable presence of the Knights Templar. When I viewed the events and circumstances leading up to the battle, I developed an entirely new theory about the Templars’ role in it.

Rosslyn Chapel has been described as being closely associated with the Knights Templar. Was it? Or was it simply an extraordinary collegiate chapel that was used by the Saint Clair (Sinclair) family for worship and burials? Is the symbolism tied to the Templar myths and mysticism? Or is it simply representative of the time? In Chapter 9, ‘Rosslyn Chapel: a Templar Legacy?’ I discuss these and other points.

This brings up the initial question, is there an unbroken Templar link in Scotland? What happened to the Knights Templar after the Battle of Bannockburn? After their formal dissolution, how were the Templars in Scotland involved with the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem (the Hospitallers)? Were there periods when the Templars went into decline? Did they disappear to the outside world? The answers do not appear to be a part of what we accept as recorded history. After three years of research, the answers to these and several other questions begin to come together in Chapter 10. Also, there may be secret histories in the files of the Templar Orders in Scotland that are considered too controversial for release. Or they may simply be inconsistent with known facts and recorded history. I do not know all the answers, but Chapter 10 contains some of them. It and Chapter 8 are written with the hope that they open avenues for further exploration and disclosure.

Chapter 11, ‘The Modern Scottish Knights Templar’, is an overview of today’s Templar Orders in Scotland. Thanks to the internet, anyone can go online and look up the websites for most of the modern Templar organizations. But I have found that a background and history exists for a number of the modern international and Scottish Orders that is not online. In terms of Scotland, the Templars are in the midst of a strong revival.

1

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR OF JERUSALEM

Who were the Knights Templar? What were they? These questions are particularly important in the context of Scotland because in Scotland their purpose was purely economic, and their only engagements were Bannockburn and the battles that led up to it. But still, in Scotland the Templars had a purpose, and no less a mystique than the mystique that existed in France and Palestine. To that end, this chapter describes who the Templars were and what they did. It is not meant to be exhaustive. For this, there are several books listed in the Bibliography.

If the Templars fled to Scotland after their arrest in France, would they have been inclined to stay there? The answer to this question is found in the description of how the Templars lived, and what aspects of their lifestyle in Europe and Palestine were consistent with their life in Scotland. There is also the question of whether the Templars were present at the Battle of Bannockburn. Would the Templars have remained in a fighting mode for eight years?

The Knights Templar are often described as ‘warrior-monks’. Most authors emphasize the Templars’ battles, with some discussion of their extensive commercial and banking activities. But there is little discussion about a Templar Knight’s daily life, or how he lived as a monk. Because Scotland involved no Templar battles, and was exclusively a commercial center devoted to raising money, a more complete picture of the Templars is essential.

The Order began as the Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, and ultimately became the Ordo Supremus Militaris Templi Hierosolymitane, the Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem, or the Knights Templar. It was formed in 1119 by Hughes de Payens and Godfrey of Saint Omer to defend Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land during their pilgrimages to Jerusalem. 1 The Order was made up of knights and other nobles who took the vows of a monk. It became the world’s most effective fighting force and first multinational conglomerate.

The Order was formed as a result of the First Crusade that ended in 1099 with the capture of Palestine (known to Europeans as ‘Outremer’, the land beyond the sea) and the city of Jerusalem. With the capture of Jerusalem came a flood of pilgrims from Europe to visit the Holy Land. There were an immense number of pilgrims and their need for protection was the catalyst for the formation of the Knights Templar.

The Templars’ primary founder, Hughes de Payens, was a knight who came from the village of Payens in the province of Champagne on the left bank of the River Seine in northern France. He was a vassal of, and owed his allegiance to, Hugh, the Count de Champagne. The Templars originally consisted of nine knights: Hughes de Payens, Godfroi de St Omer, Roral, Gundemar, Godfrey Bisol, Payens de Montidier, Archambaud de St Aman, Andrew de Monthar and the Count of Provence.2 The number of knights remained essentially the same for nine years. The only known change was the addition of Hugh, Count de Champagne, in 1226. He was a powerful noble who brought a great deal of credibility to the early Templars. The Templars’ purpose was to assist and protect the pilgrims as they traveled from Mediterranean ports, usually Jaffa or Tyre, to Jerusalem, and from there to the other holy places in Palestine. This need existed because the Christians held the cities and holy places, but could not control the routes in between. As a result, the routes were constantly under threat by marauders, thieves and the people who had been dispossessed of their homes as a result of the First Crusade.

Housing for the original knights was unusual. Initially they had none. But at Hughes de Payens’ request, Baldwin I of Jerusalem permitted the Templars to live in a wing of his palace over the catacombs of the former Temple of Solomon. It is not known how the original nine Templars, who lived in poverty and relied on handouts for food and clothing, were able to protect travelers and stay alive in Outremer for nine years. First, disease was a significant problem for Europeans who traveled to Palestine. Then there is the question of how only nine knights could protect thousands of pilgrims and themselves, and stay alive against the Arabs who continued to fight as bands of mounted armed outlaws.

It is believed by many that the Templars’ primary purpose during the first nine years was excavation in the catacombs beneath the ruins of the Temple of Solomon.3 What was found is a matter of great discussion, debate and dispute. There are various suppositions. They range from the Holy Grail, to the Ark of the Covenant, to an immense amount of precious metals and jewels, to the scrolls of Jesus’ brother James the Just, to evidence of a marriage between Jesus of Nazareth and Mary Magdalene, 4 to nothing at all. Some of the theories do appear to have a historical basis. Early in Templar history (apparently within the first nine years), Hughes de Payens is said to have written that ‘although Christendom seemed to have forgotten them [the Templars], God had not, and the fact that their work was in secret would win them a greater reward from God.’5 But there is no evidence that indicates why the Templars’ work was in secret, or what their work was.

The evidence that does exist simply confirms that the Templars explored the catacombs under the Temple of Solomon. In the latter part of the nineteenth century Lieutenant Charles Warren of the Royal Engineers was part of a team that conducted an excavation of the catacombs. Among a number of discoveries, Lieutenant Warren found a variety of Templar artifacts, including a spur, the remains of a lance, a small Templar cross and the major part of a Templar sword. These artifacts are now in Scotland and are part of a private collection owned by Robert Brydon, a Templar historian and archivist.

Much has been written about the Templars’ battles, their victories, and defeats. Likewise, much was also written about their downfall, the charges that were ultimately brought against the Templars in 1307, and their trials for heresy.6 But little has been written about just who they were, how they lived, their organization, or whether they continued to exist in Scotland after they were officially suppressed and disbanded in 1312 by Pope Clement V. The Templars lived a life that conditioned them to be organized and devout. Their duties involved not only fighting in battles, but living an austere life that focused on the preservation of their Order, their traditions and their property.

To understand the Templars one must first look at what knights generally were, and what they were not. In the Middle Ages, knights were not looked upon favorably. As succinctly put by Peter Partner in The Knights Templar and their Myth:

Far from idealizing chivalry, religious leaders usually represented knightly life as lawless, licentious, and bloody. The Clergy were absolutely forbidden to shed blood, and to combine the life of an active soldier, killing and plundering like any other soldier, with the life of a monk, was to go against a fundamental principle.7

But this description did not apply to the Templars. The Templars’ mentor, Abbot Bernard de Clairvaux, who ultimately became Saint Bernard, and who is depicted in a fifteenth-century painting shown in Figure 1, was strident in his belief in the Templars, and was eloquent in his expression. This is illustrated in his essay ‘In Praise of the New Knighthood’, which he wrote in the early 1130s to Hughes de Payens. In modern terminology, it was a masterful sales tool for recruiting knights, and soliciting support and gifts. The following quotes are examples:

The new order of knights is one that is unknown by the ages. They fight two wars, one against adversaries of flesh and blood, and another against a spiritual army of wickedness in the heavens.

[…]

Truly, his is a fearless knight and completely secure. While his body is properly armed for these circumstances, his soul is also clothed with the armour of faith. On all sides surely his is well armed; he fears neither demons nor men. Truly does he not fear death, but instead he longs for death. Why should he have a fear for life or for death, when in Christ is to live, and to die is to gain? He stands faithfully and with confidence in the service of Christ; he greatly desires for release and to be with Christ, the latter certainly a more gracious thing.

[…]

Even more amazing is that they can be gentle like a lamb, or ferocious like a lion. I do not know whether I should address them as monks or as knights, perhaps they should be recognised as both. But as monks they have gentleness, and as knights military fortitude.8

As the Order evolved, the Templars were ultimately governed by a detailed set of regulations, appropriately named the ‘Rule’. What caused the Rule to be written is a matter of dispute. According to Malcolm Barber, the guiding hand was Saint Bernard, but the actual wording of the Rule was a ‘fairly exhaustive process of committee discussion’.9 This view is disputed by Lynn Picket and Clive Prince who contend that ‘Bernard actually wrote the Templars’ Rule – which was based on that of the Cistercians …’10

Regardless of how the Rule was written, it absolutely controlled the life of a Templar Knight, whether he was fighting in the east or involved in commerce in the west. Under the Rule, a Templar’s lifestyle was beyond austere. He lived as a monk who cropped his hair, let his beard grow and, to avoid temptations of the flesh and to be ready when needed, he always slept clothed.11 The Templar Knight ate meat only three times a week.12 He spent a great deal of his time in silence.13 There was no gossip or small talk.14 The knight lived in a dormitory-like building and was allowed no privacy. He could not use or own locks. If he received a letter it had to be read to him out loud in the presence of the Master15 or possibly a chaplain.

While the Templars did not have the powers and sanctity of the priesthood, each day when he was not in battle, which was most of the time, he performed the six liturgical prayers. This occurred every day of a knight’s life. The normal Templar’s day began early at 4 a.m. with the day’s first liturgical prayer, Matins. The Templar brothers would recite thirteen Paternosters (Lord’s Prayers) and prayers to Our Lady. They would then tend to their horses and equipment. This was followed by Prime at 6 a.m. which included more prayers and Mass. Then at 11.30 came Sext and the reciting of additional Paternosters and prayers to Our Lady.

After Sext came the afternoon meal, which was eaten in silence. At 2.30 came Nones and more prayers. Then Vespers at 6 p.m. was followed by the evening meal. The sixth and final liturgical prayer was sung at Compline, after which the Templar Knight would attend to his horses and then retire.16

In between the times for prayer and meals, the primary tasks for the Templar Knight in Outremer were tending to his horses and arms, and keeping ready for battle. Each knight also worked in the fields and filled in where needed with other simple tasks. The Templars were not permitted to, and never did, remain idle. This routine was followed day in and day out. It did not vary. It applied to all Templars, including knights and sergeants, and all those who abandoned secular life and chose the communal life of the Templars.17 Once one became accustomed to the routine it became part of the Templar’s life, whether he be a knight, sergeant, chaplain or a committed menial worker. The routine was followed in Outremer and in all parts of Europe and the British Isles. The level of commitment is demonstrated by the amount of torture that the French king had to exert, or threaten, before he could begin to extract confessions after the knights’ arrests.

On the battlefield the Knights Templar were not only superlative horsemen who constantly trained to perfect tight formations, but were fearless, and dedicated to victory over the Saracens. To this end, they were not permitted to retreat unless the odds against them were at least three to one. In some cases the Templars did not retreat until their forces were outnumbered six to one. Even then, they could not leave the field unless ordered to do so. Surrender was useless because the Templars could not use their funds for ransom. As a result, Templars taken in battle were either traded or, more often, summarily executed.18 After 1229, when the Templars became an organized fighting force, with up to four horses per knight, a squire and excellent armament, the average lifespan of a Templar Knight who chose to remain in Outremer was about five years.

Even before the adoption of the Rule, each Templar Knight took vows of absolute poverty, chastity and obedience before Warmund of Picquigny, Patriarch of Jerusalem.19 Surprisingly, only two of the three vows were incorporated into the Rule. Poverty was assumed. The applicable Rules and practices were severe:

Chastity was a very important vow. In the charges brought by King Philip IV of France, sexual deviancy was almost a theme. Yet the writers and commentators are uniform in their opinion that there was little if any lewd or untoward conduct among the Templars. What faults there were lay in the areas of secrecy and avarice which is discussed in later chapters. Chastity was codified in the Rule, article 71, which states:

We believe it to be a dangerous thing for any religious to look too much upon the face of woman. For this reason none of you may presume to kiss a woman, be it widow, young girl, mother, sister, aunt or any other; and henceforth the Knighthood of Jesus Christ should avoid at all cost the embraces of women, by which men have perished many times, so that they may remain eternally before the face of God with a pure conscience and sure life.

Obedience was absolute. It was codified in the Rule at article 39, which states that:

For nothing is dearer to Jesus Christ than obedience. For as soon as something is commanded by the Master or by him to whom the master has given the authority, it should be done without delay as though Christ himself had commanded it.

While there is no specific article in the Rule which commands poverty, the specifics of how a Templar Knight lived left no alternative. Poverty is recognized in the Rule at article 58, which deals with tithes which could be received on behalf of the Order. It states:

You now have abandoned the pleasant riches of this world, we believe you to have willingly subjected yourselves to poverty; therefore we are resolved that you who live the communal life may receive tithes.

Even though the Templar brothers in Scotland were involved only in real estate, commerce and money markets, the Templar Knights lived by the Rule and it was strictly enforced.20

THE TEMPLAR HIERARCHY

Every large organization has its bureaucracy. This was as true in the Middle Ages as it is today and the Order was no exception. The Templars not only had a bureaucratic hierarchy, it had specific job descrip-tions. These primarily evolved between 1129–1160 when the Templars established what today would be called an organization chart or its organizational ‘hierarchy’. The hierarchy demonstrates that some things never change. Not even in 800 years. The Templars’ organization chart looks just like many seen today.

The Templars’ organizational hierarchy was used, to some extent, in Scotland. Some of the offices were the same, others were unique to Scotland. But an understanding of how the Templar organization worked in general, provides a basis for understanding how it was adjusted to accommodate the conditions in Scotland.

The organizational hierarchy was logically codified in the portion of the Rule known as the Hierarchical Statutes. Each of the offices is described separately and listed in sequence, the higher offices first.

Grand Master: The Master of the Temple of Jerusalem was the ultimate leader of the Knights Templar. Although his powers were extensive and his authority in battle absolute, the Rule expressly required that the major internal decisions had to be approved by a Council of Knights, of which the Master was a member, with one vote.21

Seneschal: The Seneschal was second in command to the Grand Master and had the Grand Master’s full authority in his absence. As the Grand Master’s ‘right-hand man’ he carried the beauseant or piebald, the Templars’ black and white banner with the white above and the black below.22

Marshal: The Marshal was third in command. He was in charge of all arms and animals used in battle. He was also responsible for the distribution of gifts, alms and booty. In the absence of the Master and the Seneschal, the Marshal was the supreme military commander.23

Commander (Grand Marshal/Prior) of the Kingdom of Jerusalem/Grand Treasurer: He was the commander for the province of Jerusalem and was the treasurer for the entire Order.24

Commander (Master) of the City of Jerusalem: He ran the city and continued the original task of the Knights Templar: protecting pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. There was a Master for each country who ruled over the commanderies and preceptories in each respective country, such as France, Germany, Italy, Spain and England. The Templars in Scotland were ruled by the Commander or Preceptor at Balantrodoch who reported to the Master in London.25

Draper: The Draper was the quartermaster. He was in charge of clothes and bed linen.26

Turcopolier: The Turcopolier was the light cavalry commander who developed several battle formations. As described in Chapter 10, one of these is said to have been used by Scottish knights in Spain against the Moors when they were attempting to take the heart of Robert the Bruce to Outremer.

The Rule describes the commanders and sergeants who were responsible for the localized units, specifically the local properties of the Templars, forts, farms, and estates which were called ‘houses’. These were governed by Commanders of the Houses who reported to the Provincial Master or Grand Prior. England and Scotland were not separated and were governed by a Master of the Temple in London. Scotland was governed by a Commander or Preceptor at Balantrodoch just south of Edinburgh, which is described in detail in the next chapter.

Specific levels or classes in the Templar brothers existed. For example:

A knight was noble before he joined the Order. He did not become a knight by joining. Upon joining the Order he surrendered his property, if he had any, took monastic vows and became a monk. He wore a white mantle with a red eight-pointed cross.27

An associate was a noble who joined the Order for limited periods of time or a fixed term.28 For example, a married man would become involved for a while. Another might join the Order for a particular crusade. After his term was up, he would return home to his family and estate.

A sergeant (or esquire) was a younger, lightly armed troop and/or a squire to a knight. He was required to be a free man to be qualified to join. He wore the red eight-pointed cross on a brown or black mantle. He was not allowed to wear a white mantle.29 At the inquisition of the Templars in Scotland, only two knights were questioned; the majority of the brothers in Scotland were undoubtedly sergeants whose job it was to conduct the overall management of the Templar properties. None were arrested, and the records show that they simply went on as before.

A Templar chaplain replaced and was separate from the church or diocesan authority. The chaplain conducted all of the Templars’ various religious services and ceremonies. He answered only to the Pope.30

Craftsmen and menials were the manual laborers, artisans and domestic servants who are said to have been the largest group of Templar personnel. They performed the day-to-day work.31 The elite of this group were the stonemasons.

In Scotland the most numerous group were the baillis who may have played a significant role in the Templars’ continued existence in Scotland after their formal dissolution. An individual baillis would manage a larger estate or house. Others would manage a number of smaller properties. None were arrested during the inquisition in Scotland. They and their successors continued to manage the Templar properties in Scotland for several hundred years.

WARRIORS AND ENTREPRENEURS

The Templars’ roles as warriors and entrepreneurs began in 1229 after the Council of Troyes. In late 1227 or early 1228 Hughes de Payens left Palestine and returned to France, where he began an earnest campaign to solicit gifts and gain recruits. He met with the kings and nobility of France, and then traveled to Normandy where he met with Henry I, the King of England, who gave him ‘his blessing and great treasures’. Henry I then sent him off to raise funds and to recruit additional knights from England and Scotland.32 Before and at the Council of Troyes, Hughes de Payens had a long dialogue with Abbot Bernard de Clairvaux, which ended with the Abbot’s full support. As a result, the Templars established a strong foothold in France, England and Scotland.33 Ultimately, the Templars acquired land in Outremer, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Germany. ‘If the brothers in the Holy Land were the spearhead, those in Europe were the shaft, supplying arms and armor, men, money, horses and food.’34

The Templars ultimately formed the predecessor to what is today’s multinational conglomerate.35 They owned churches, forts, farms and extensive landholdings throughout Europe and Outremer. They became very skilled in farming, particularly on barely profitable land, because nobles often donated land that was not economical for them to farm themselves. Another area in which the Templars excelled was stonemasonry; there was a specific rule that expressly permitted masons to wear gloves, when all the other brothers, except chaplains, could not.36

The Templars also owned a substantial fleet of ships. Because of their military ability and reputation, they were able to safely move goods and money. They controlled the Atlantic coast from their port at La Rochelle, the Mediterranean from Marseilles, and the east from Acre in Outremer. They were multinational bankers who held money and wealth on deposit for monarchs and nobles, and also loaned them substantial amounts. The Knights Templar invented the letter of credit. These originated with travelers depositing money in London or Paris, and then drawing the equivalent in a different currency at their destination in the east. This, of course, generated a fee. The practice was quickly incorporated into the practices of secular bankers. While the Church prohibited the charging of interest, the Templars and other bankers could charge fees and levy penalties.

Another area where the Templars were self-contained was in healthcare.37 The Rule is very specific about providing care and consideration to brothers who became sick.38 They had their own hospitals, 39 physicians and surgeons. The Templars could provide excellent healthcare because they had become intimately familiar with near eastern medicine which was substantially superior to the primitive methods used in Europe. They are even believed to have had an understanding of antibiotics.40 If a Templar contracted leprosy, which was not uncommon, he was given the option of transferring to the Order of St Lazarus.41

It is more exciting to write about the Templars’ battles, and to depict the Templars primarily as warriors. But warriors spend a great deal of time in between battles, and the knights of the Knights Templar were no exception. They spent the majority of their time performing maintenance on their weapons, caring for their livestock, tending to their agriculture and banking. On a daily basis, the knights were monks and they lived communally. Each was provided according to his need. No one knight was elevated above another.42 They not only said grace at each meal, 43 but they read from the Holy Scripture.44 They celebrated nineteen feast days.45 They had specific rules for attendance at chapel, 46 and on Fridays the knights ate only Lenten food, which was eaten collectively.47 In the evening, each day ended with prayers.48 And so it went, every day for approximately 183 years between the Council of Troyes in 1129 and the Templars’ formal dissolution in 1312, from England and Scotland, across Europe to Outremer. This represents a significant amount of structure and tradition. To attempt to end the Templars’ long conditioned lifestyle on a particular day, such as the day of the Templar arrests on Friday 13 October 1307, or with the stroke of a pen by Pope Clement V on 3 April 1312 when he signed the decree dissolving the Templars, would be next to impossible.

THE HISTORY OF THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR

The Templars may have originated in 1118, when Hughes de Payens and eight other knights began protecting pilgrims traveling in the Holy Land, but their chronicled history begins in 1128 after the Council of Troyes. It was then that the Templars began their defence of the Holy Land, and they led its occupation for 162 years.

The Council of Troyes took place in the cathedral at Troyes on 13 January 1128, St Hilary’s day. It is near to both the towns of Payens (now ‘Payns’) and Clairvaux in northern France. We know exactly what happened at the council because the proceedings were recorded by John Michael, who Bernard de Clairvaux chose to be the council’s scribe. The council was presided over by Matthew du Remois, Cardinal-Bishop of Albano, the papal legate. Hughes de Payens was accompanied by the Templars’ co-founder, Godfrey de Saint-Omar, and four other original Templars, Roland Geoffroi Bisot, Payen de Montdidier and Archambaud de St Aman.49 The cathedral was full of members of church hierarchy in their ornate clerical garb, and richly clad nobles. The Templars wore closely cropped hair, bushy beards and old, tattered clothes.

Hughes de Payens was the primary speaker at the council. His speech described the Templars’ life, hardship, and purpose in Outremer. It ended with a plea for formal support from the Church, rules to live by, funds and recruits. The requests were approved by the Abbot Bernard de Clairvaux, and were accepted by all those who were present. Church acceptance was gained by the approval of Pope Honorius II. The rules to live by were detailed and harsh. They were achieved by the adoption of the original seventy-two articles of the ‘Rule’ of the Temple, which is also known as the ‘Latin Rule’ or the ‘Primitive Rule’.50 Funds and recruits came in as Hughes de Payens toured Europe and the British Isles.