Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

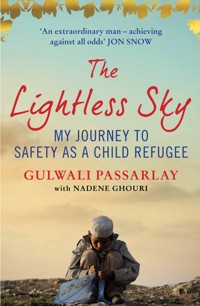

The boy who fled Afghanistan and endured a terrifying journey in the hands of people smugglers is now a young man intent on changing the world. His story is a deeply harrowing and incredibly inspiring tale of our times. 'To risk my life had to mean something. Otherwise what was it all for?' Gulwali Passarlay was sent away from Afghanistan at the age of twelve, after his father was killed in a gun battle with the US Army. Smuggled into Iran, Gulwali began a twelvemonth odyssey across Europe, spending time in prisons, suffering hunger, making a terrifying journey across the Mediterranean in a tiny boat, and enduring a desolate month in the camp at Calais. Somehow he survived, and made it to Britain, no longer an innocent child but still a young boy alone. In Britain he was fostered, sent to a good school, won a place at a top university, and was chosen to carry the Olympic torch in 2012. Gulwali wants to tell his story - to bring to life the plight of the thousands of men, women and children who are making this perilous journey every day. One boy's experience is the central story of our times. This memoir celebrates the triumph of courage and determination over adversity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 596

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LIGHTLESS SKY

My Journey to Safetyas a Child Refugee

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2015by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2019 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Gulwali Passarlay, 2015

The moral right of Gulwali Passarlay and Nadene Ghourito be identified as the authors of this work has been assertedby them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Map copyright © Jamie Whyte, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 178 6497154E-book ISBN: 978 178 2398462

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my Mother.

And for the 60 million refugees and internallydisplaced people who are out there somewhere inthe world today, risking their lives to reach safety.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Map: Gulwali’s Journey. Credit: Jamie Whyte

Images

1: Gulwali, aged 8, selling tailor supplies

2: Gulwali, aged 10, and his younger brother Nasir in Afghanistan

3: Laghman Province, Afghanistan. Credit: Naveed Yousafzai

4: Gulwali, aged 10, with his family in Afghanistan

5: Gulwali’s Afghan passport photo, 2008

6: Gulwali with his foster father, Sean

7: Gulwali’s proudest moment so far: carrying the Olympic torch in 2012. Credit: Capture the Event

THE LIGHTLESS SKY

My Journey to Safetyas a Child Refugee

PROLOGUE

Before I died, I contemplated how drowning would feel.

It was clear to me now; this was how I would go: away from my mother’s warmth, my father’s strength and my family’s love. The white waves were going to devour me, swallow me whole in their terrifying jaws and cast my young body aside to drift down into the cold, black depths.

‘Morya, Morya,’ I screamed, imploring my mother to come and snatch up her twelve-year-old son and lift him to safety.

The journey was supposed to be the beginning of my life, not the end of it.

I have heard somewhere that drowning is a peaceful death. Whoever said that hasn’t watched grown men soil themselves with fear aboard an overcrowded, broken-down boat in the middle of a raging Mediterranean storm.

We’d eaten what little food and water the captain had on the boat within the first few hours. That had been more than a day ago. Now, fear, nausea and human filth were the only things in abundance. Hope had sunk some time during the endless night, dragging courage down with it. Despair filled my pockets like stones.

When we had set sail from Turkey, the white-haired Kurdish smuggler had promised we would reach Greece in a couple of hours. The man worked for a powerful, national-level agent, one of the shadowy businessmen who own and control the trade flow of desperate migrants moving through their countries. Money exchanges hands and deals are struck through a series of regional agents and local middle men. A powerful agent might have several junior agents and hundreds of local-level smugglers, drivers and guides in his employ, dealing with hundreds or even thousands of migrants and refugees at any time.

Yet, despite the Kurdish man’s promises, it had been two days since we had set sail and we were still at sea.

On the morning of the second day, far out to sea, the captain changed the boat’s flag from Turkish to Greek. This should have been a good sign, but something felt wrong. If we were in Greek waters, why hadn’t we docked yet?

Everyone guessed that something had gone awry and the majority of the men, many of whom were locked below in the hull, began to panic. These were the men who had been first to board, the ones who had shoved weaker men aside so that they might be guaranteed a place on the boat. As they had got on, the captain had instructed them to go below. How could they have known that they would then be locked in behind a metal door? They hadn’t expected to be trapped in a floating coffin, and had been screaming half the night, desperate to get out. I thanked the Creator I wasn’t in there with them.

I had been one of the last to get on and I had been worried that I wouldn’t get a space. By the time I was aboard, the hull had been already full and I was placed on the open deck – a lucky stroke of fate. As the only child on the boat, my chances of survival weren’t great even at the best of times, but at least being on the open top deck allowed me a fighting chance.

There was no toilet anywhere on board. Men had soiled their clothes; others urinated into empty water bottles – some even saving the yellow liquid to drink. Desperation can be a great motivator. A foul mix of sea water, urine and faeces constantly lapped at our feet and, even in the open air, the stench burned my nose. Added to this, my bottom ached from sleeping and sitting on the hard wooden bench that ran around the edge of the deck. It was impossible to snatch more than a couple of minutes’ sleep at a time. We were wedged so tightly together the only way to sleep was sitting up.

Hamid, a youth in his early twenties I had met just six days earlier, as we had hidden in a forest waiting for this boat journey, was sitting next to me. We took it in turns to rest our heads on each other’s shoulders. My only other friend, Mehran, was one of the unfortunates trapped below deck. During the nights I heard him screaming in terror: ‘Allah, please help us. Allah.’

The only reprieve came on the second night, when the captain allowed me and Hamid to go on to the roof of the boat. I don’t know why I was chosen – maybe he felt a bit sorry for me because I was a small boy travelling alone.

Big waves rocked the boat incessantly, but being high up felt safer, somehow. It was such a relief to get fresh air and to be able to stretch my arms and legs, but at the same time I was terrifyingly conscious that even the slightest wrong movement could see me topple over the side and into the waves. I had no idea how to swim: if I fell in I’d be dead. I didn’t expect that anyone would jump in to save me.

By dawn of our third day at sea our captain had become extremely agitated, constantly shouting into his radio in Turkish. I suppose he knew we couldn’t stay out there for much longer without food or water.

I overheard a couple of the passengers, both Afghans like me, discussing whether it made sense to take control of the boat.

‘Let’s attack him and tie him up,’ said one.

His friend shook his head. ‘You fool. Who would get us into Greece if we did?’

The second man was right.

Like it or not, we were at the captain’s, and the sea’s, mercy.

By this point, I was beginning to feel delirious from lack of food and fresh water, and had started to hallucinate. My throat was so parched with thirst I was unable to breathe through my dry mouth. I kept thinking how nice it would be in Greece – just to wash my body, and not stink of piss and vomit. It sounds so stupid but rather than food, I began to fantasize about new clothes and how good they would feel on clean skin.

I was too focused on trying to stay alive to think much about the family I had left behind. Remembering them made me so unbearably sad, especially when I thought about my thirteen-year-old older brother, Hazrat. We had fled Afghanistan together, in fear for our lives, but he had been ripped away from me by the smugglers just days after we’d escaped.

It helped to try and focus on my mother’s steely determination and imagine her voice urging me not to give up: ‘Be safe, and do not come back.’ They had been her last words to me and my brother before she had sent us both away to find sanctuary in strange lands. She had done it to try and save our lives, to help us escape from men who had wanted us dead.

But so many times I wished she hadn’t.

Sometime in the afternoon of the third day, the engine started to choke and splutter, and then it cut out completely. The captain pretended for a while that everything was OK, but as time wore on he became even angrier, sweating and swearing as he tried to restart the ancient diesel motor. Eventually he got on to his radio again and started shouting at someone, this time in a language I didn’t recognize.

Finally, after one particularly heated conversation, he asked a Turkish speaker to translate to us all.

‘They are sending a new boat to get you. Don’t worry.’

The captain smiled around at us all, displaying black, decaying teeth, but the look in his eyes gave the truth away, filling me with intense dread. Not all of us were going to survive, of this I was certain. I felt rage swell inside me at the slippery lies that had come so easily from him.

My fears were confirmed when the weather worsened. Curling tails of wind whipped the waves into frenzy, wailing like demonic beasts.

‘Morya, Morya. I want Morya.’ I screamed for my mother, the mother who was far away in Afghanistan. I was a lost little boy, about to meet his death in a cold, foreign sea.

Before getting on this boat, I had never even seen the sea before; the only knowledge I had had of it was from pictures in school text books. The reality was beyond the wildest reaches of my imagination. For me, those waves were truly the entrance to the gates of hell.

I managed to get into a higher position – on the roof of the wheel house. The move gave me air and space, but now each rushing wave swung me back and forth like a rag doll. My skinny fingers gripped the railings, my knuckles white and bloodless.

After a couple of hours of this, the boat began taking in water. Everyone started screaming, the people trapped below frantically pummelling at the locked door with fists and shoes.

‘We are going to drown, let us out. For God’s sake, let us out. We will die here.’

The captain waved a pistol and fired in the air, but no one paid him any attention. It seemed sure that the boat would overturn.

For a brief, strange moment I was calm, resigned: ‘So, Gulwali, this is how you will die.’ I imagined it – drowning – in explicit detail: the clean coolness of the water as darkness closed overhead, my life starting to flash before my eyes: my grandparents’ wizened, wise faces; me at four years of age tending sheep by a mountain brook; walking proudly beside my father through the bazaar, him with his doctor’s microscope tucked underneath his arm; sheltering from the baking sun under the grape vines with my brothers; the scent of hot steam as I helped to iron the clothes in my family’s tailor shop; my mother’s humming as she swept the yard.

No.

I wasn’t giving up.

I had been travelling for almost a year. In that time, any childhood innocence had long since left me. I had suffered unspeakable indignities and dangers, watched men get beaten to a pulp, jumped from a speeding train, been left to suffocate for days on end in boiling-hot trucks, trekked over treacherous, mountainous border crossings, been imprisoned twice, and had bullets fired at me by border guards. There had rarely been a day when I hadn’t witnessed man’s inhumanity to man.

But, if I’d made it this far, I could make it now. A survival instinct deep within me spurred me on. I didn’t want to die, not here, not like this, not gasping and choking for breath in the cold depths of the sea. How would anyone find my body?

My mother’s face flashed before me again. ‘It’s not safe for you here, Gulwali. I’m sending you away for your own safety.’

How would she feel if she could see me now? Would she ever know what had happened to me?

That thought was enough to give me strength. I knew the captain had lied to us again – there was no other boat coming to get us, and this one was sinking fast. There was no way I was going to follow his orders to stay down and hide.

I searched in my bag and pulled out the red shirt I’d managed to buy in Istanbul, the one I was saving to wear as celebration for getting to Greece. I started waving and screaming: ‘Help, help. Somebody help us.’

I hadn’t realized it, but the captain was behind me. As I turned, he kicked me full in the face, sending me tumbling down to the deck and almost over the side. Dazed and in agony, I clung on to the railing for dear life. The boat rocked back and forth but still I held my hand as high I could, waving my shirt. The captain came for me again. I think he may have intended to push me overboard but by then others had followed my lead and had started screaming for help too, waving whatever they could to attract attention.

The boat gave a heavy belch and the bow dropped deeply into the water. Everyone screamed again and tried to move to the stern; I was still dazed from the captain’s kick so could only try to protect myself from the stampeding legs.

The boat was finished, it was obvious. With a sickening wheeze, the stern settled heavily in the water too.

Now, we truly were sinking.

I closed my eyes and began to pray.

CHAPTER ONE

‘I found you in a box floating down the river.’

I eyed my grandmother suspiciously.

Her deep brown eyes danced mischievously, set within a face that was deeply lined and etched by a lifetime’s toil in the harsh Afghan sun.

I was four years old, and had just asked the classic question of where I’d come from. ‘You are joking with me, Zhoola Abhai.’

Calling her ‘old mother’ always made her smile.

‘Why would an old woman lie? I found you in the river, and I made you mine.’ With that she gave a toothless chuckle and wrapped me in her strong arms – the one place in all the world where I felt most safe, loved and content. I was my grandparents’ second grandchild, born after my older brother, but I felt like I was their favourite, with a very special place in their hearts.

We are from the Pashtun tribe, which is known for both its loyalty and its fierceness. Home was the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar, the most populated province in Afghanistan, and also a place of vast deserts and towering mountains. It is also a very traditional place, where local power structures run along feudal and tribal lines.

I was born in 1994, just as the Taliban government took control of Afghanistan. For many Afghans, and for my family, the ultra-conservative Taliban were a good thing. They were seen as bringing peace and security to a country that for over fifteen years had suffered a Russian invasion, followed by a brutal civil war.

For much of their marriage, my grandparents had lived in a refugee camp in the north-western Pakistani city of Peshawar. The refugee camp was also where my parents had met and been married. By the time I was born, Afghanistan was not at war, and relatively stable under Taliban rule.

My earliest memory is of being four years old and running with my grandfather’s sheep high in the mountains. Grandfather, or Zoor aba (‘old father’), as I called him in my native language of Pashtu, was a nomadic farmer and shepherd. He was a short man, made taller by the traditional grey turban he always wore. His hazel-flecked green eyes shone with a vital energy that belied his years.

Each spring he walked his flock of thickly fleeced sheep and spiral-horned cattle to the furthest reaches of the mountains in search of fresh and fertile pasture. My grandparents’ home, a traditional tent made from wooden poles and embroidered cloth, went with them. Two donkeys carried the tent on their backs, along with the drums of cooking oil, sacks of rice, and the flour my grandmother needed to bake naan bread.

I would watch transfixed as my grandmother spread and kneaded sticky dough along a flat rock before baking it over the embers of an open fire. She cooked on a single metal pan which hung from chains slung over some branches balanced over the fire. I loved helping her gather armfuls of wild nettles which she boiled to make a delicately scented, delicious soup. I don’t know how she did it, but everything she created in that pan tasted of pure heaven to a constantly hungry little boy like me.

Every year, as the leaves began to turn into autumn’s colours, they would head back down to lower ground, making sure to return to civilization before the harsh snows of winter descended and trapped them on the mountains’ slopes. There they joined the rest of their family, their six children and assorted grandchildren, in the rambling house that was home to our entire extended family. Our house then was a very simple but lovely, single-storey stone-built structure perched above a clear, flowing river.

I was my grandparents’ shadow so I was thrilled when, aged three, they took me with them the next time they returned to the mountains. Their youngest daughter, my auntie, Khosala (‘happy’), was also with us. She was fifteen and like a big sister to me.

For the next three and a half years I shared my grandparents’ nomadic lifestyle, at night falling soundly asleep beneath a vast, star-filled mountain sky, safely tucked up inside the tent nestled between the pair of them.

Grandfather loved his family with a fierce passion, and laughter came easily to both him and my grandmother. I don’t think I ever saw him angry. One time I accidentally almost took his eye out with a catapult. Blood was streaming down his cheek from where my badly aimed flying rock had cut it. It must have really hurt but he didn’t chastise me. Instead, with characteristic humour, he managed to make a joke of it: ‘Good shot, Gulwali.’

My grandmother was sturdily built and bigger than my grandfather. She was definitely the boss, but I could see they adored each other. Love isn’t something people really discuss in Afghanistan. Families arrange marriage matches according to social structure, tribal structure or even to facilitate business deals; no one expects or even wants to be in love. You just do as your parents demand and make a marriage work the best you can – you have to, because divorce is culturally so very shameful that it is practically forbidden.

It was explained to me once – by my grandfather – that a woman is too flighty and unsure of her own mind to understand the consequences of leaving her marriage. Besides, who would look after her if she did? I knew only of one woman whose husband had divorced her. She’d been taken in by her brother but this was a great embarassment and shame to their family. She had been lucky that he had accepted her and hadn’t turned her away on to the streets.

My grandparents would never have dreamt of breaking up, even if they could have done. They had married when she was fifteen and he eighteen, meeting for the first time on the day of their wedding, as is still often the norm. But anyone could see that their years together had given the pair a special bond.

By the time I was five I was already a skilled shepherd, able to shear off a fleece all on my own. I recognized every animal individually and loved how they knew the sound of my whistle. I particularly enjoyed watching my grandfather’s two sheepdogs working. One was a large, thick-headed beast and the other a small, wiry terrier-type dog. They would run rings around the flock, corralling them into order. And when the local vet, a man who traversed the furthest reaches of the mountains to service his clients, came to treat the sheep, I remember thinking how brilliant it might be to be a vet myself when I grew up. I was fascinated by him and the various implements he used.

It was about as wonderfully simple and rural a life as you can possibly imagine.

In winter, I would be so proud of coming back down into town with Grandfather by my side. We carried with us precious bounty from the mountains: wild fruits, honey, and koch – a type of thick, unpasteurized butter that we would spread thickly on freshly baked naan for breakfast. And Grandfather would always take me to the bustling bazaar, where he would trade his wares for supplies of rice or a new farming implement. Everything was plentiful.

Coming back down to the family home meant I got to see my parents and siblings, too. Although I loved being with the sheep, I did miss my parents. And, of course, they’d missed me too, so I was very spoilt when I came home.

As is the custom within our tribe, my parents were distantly related: my mother was my paternal grandfather’s niece, his sister’s daughter. My mother was fifteen and my father twenty when they married in the refugee camp to which my grandparents had fled after the 1979 Russian invasion of Afghanistan. During the fifteen or so long years of occupation and the civil war that followed, it is estimated that some 1.5 million people – a third of Afghanistan’s population – died, and a similar number became refugees.

In the midst of all this chaos, my grandfather had somehow scrimped and struggled enough to ensure that my father, his eldest son, became the first man in the family to receive a higher education by studying to become a doctor. This caused a huge sense of family pride, and was something which really made my grandparents role-models for us all. They were the moral heart of our family.

My father’s brothers, my two middle uncles, were also successes. They were both tailors who ran a large and profitable workshop in the bazaar. The fourth and youngest uncle, Lala, wasn’t around as often. He had a senior role within the Taliban. He used to come to visit us, bringing Taliban soldiers with him. I thought he was cool and exuded power. I knew he was an important man but didn’t really understand why or exactly what it was he did.

My mother’s parents had stayed living in Pakistan, so at that time I didn’t know them very well. My mother was one of twelve daughters. Her father was a very educated man – a mullah – and he had educated his daughters, something that was quite unusual among Pashtuns in those days. My mother was the only woman in our entire household who could read.

I think my parents were happy together: they certainly seemed it. But in Afghanistan a child knows better than to discuss or ask these things. There are certain boundaries you do not cross. I did once ask my grandmother if she liked my grandfather. She just laughed and replied: ‘I think he was the one who liked me.’ As innocent as it sounds, in our conservative community that was quite a risky thing to say, even for an old lady.

My parents had three boys by then: myself; my brother Hazrat, who was a year older than I was; and Noor, who was a year younger. Hazrat and Noor were very close, and used to pick on me a little bit. I was jealous of their little world of private jokes and unspoken communication. I think I was a bit of a loner, possibly because I was used to the solitude of the shepherding life.

My life changed completely when I was six, when my father and his three brothers ordered my grandparents back home. They worried the pair were getting too old for the nomadic life and wanted them to stay closer to the family so that they could be better looked after. There was also the matter of family honour: my father’s profession as a doctor meant he was a highly respected man in our strictly conservative community. It didn’t look good within the rigid mores of our tribal society to have the father of such a man living like a poor kochi, or nomad. Such was my father’s standing, in fact, that my brothers and I were rarely referred to by outsiders by our names: we were known as ‘the sons of the doctor’. Even Grandfather was known as ‘father of the doctor’.

Both my grandparents loved their life, so were deeply resistant to the idea at first, but in the end they gave in. Grandfather sold his entire flock of sheep – more than 200 strong – for a combination of cash and a shiny new red tractor. The whole extended family – parents, two uncles with their wives, my father’s unmarried sister Auntie Khosala, grandparents, myself and siblings – then moved to a new house in the district of Hisarak. This house was another single-storey building, made of mud and thatch, with lots of rooms running off a central, communal kitchen. Each night we ate together sitting on the floor, a bounty of food – usually rice, meat, naan and spinach – spread out on a large tablecloth in the centre of the room. It was a happy home, full of chatter and noise. I still loved the company of my grandparents and insisted on sleeping in their room.

My mother, as the senior wife, managed the running of the home, while my uncle’s wives, junior in both age and position, did the majority of the cooking and cleaning. Her outer nature, like most Afghan women, was steely and unemotional, and it was no wonder. Most women work from dawn until dusk doing housework. Washing is done by hand, while wood and fresh water must be collected daily. There is always bread to be baked and hot tea to be freshly brewed before husbands and children awake in the morning. It’s also a land where two out of five Afghan children die before their fifth birthday, so it is easier not to show too much love to children. A year after Noor was born, my parents had twin boys, who sadly both died within a few days of their birth.

But love is hard to hide when it’s a part of your very being, as it was for my mother. Under that commanding exterior, her survival mask, I often saw her gentle side – the way she would fuss over me when mending a scrape or bruise, her worry when one of us was ill, her obvious pride when recalling our accomplishments to a visitor or one of my aunts. She had a very deep voice for a woman but was tall and elegant, with a long nose and round, brown eyes. People said I looked like her. She smiled rarely, except for the secret grins that flashed across her features when I was naughty or did something funny. She was tough because she had to be but, underneath, there was an unmistakable warmness. Her family meant everything to her.

Culturally, it was a great shame to allow your women outside in case they were seen by other men, so my mother and aunts rarely left the house. On the rare occasions they did, they were completely covered by a burqa – as was the rule under the Taliban government. Inside the house they wore long shawls to cover their hair. It would have been seen as very bad for anyone outside of the immediate family, even a male cousin, to see their heads uncovered, even in the house.

I was an extremely pious child, and this was a rule I took upon myself to enforce: ‘The wrath of Allah will be upon you – go and cover your head,’ I used to say to my aunties. The young wives worked hard all day baking naan bread, and cooking over the open fire. If I wasn’t playing with my brothers or cousins, I often sat with them in the kitchen, bossing them around and ordering them to bring me tea. When my uncles were away, I would often refuse to let them walk to collect firewood, visit people or attend family weddings. I saw this as protecting the family honour. I would make a big show of insisting on collecting the wood for them so they didn’t have to: ‘Why do you need to go outside?’ I would say. ‘You are the queens of this house.’ This was something I’d heard my uncles say many times. As was another saying in Pashtu: ‘Khor yor ghor’, which was the two places for a woman: home or grave. Sometimes I would wake my aunts in the middle of the night to bring food for a newly arrived guest – my father’s profession meant people looking for help would turn up at our house at all times of the night and day.

My father was much more relaxed with the women than his brothers were, but I think I must have absorbed more of my uncle’s stricter attitudes. I was a bratty child, and I enjoyed exerting my power over my aunts. I know they loved me but I think I must have really got on their nerves at times. And if they complained about my behaviour, my uncles would tell them to be quiet and to obey me. It was not the best way to keep a child’s ego in check, but this was how it was done. In our conservative culture, males have all the power, even little boys.

The only time I got seriously told off for picking on my aunts was by my mother. One of my uncle’s wives couldn’t have children, and this was a source of consternation to the whole family. ‘If you don’t get a baby soon, I will get my uncle a new wife,’ I rudely said to her one day. The poor woman cried. My mother was absolutely furious with me and made me go and apologize at once. My aunt hugged me and I remember realizing I’d said something really mean, even though I didn’t understand the severity of it at the time. It took nine years for her to get pregnant, but she went on to have six daughters.

Another of my aunts, my father’s sister, Meena, married a man who lived outside the district. This was a really big deal because it was the first time anyone in the family had married outside the tribe, and people were not happy about it.

Auntie Khosala was next to be married. She and I had a special bond because of all the time we’d spent together in the mountains, and I felt sad for her because although she couldn’t read – she was naturally very smart – the man she married, her first cousin, was not only illiterate but obviously thick. But the match had been arranged when she was a baby: my grandmother had been pregnant at the same time as the wife of Grandfather’s brother, and when the babies were born within days of each other, my grandfather and his brother had decreed that the two infants would marry when they were older. Within our culture these things are not said lightly; once said, they cannot be unsaid, and must go on to happen.

Aside from being a farmer’s wife, my grandmother was also a traditional midwife. Pashtun men do not like to take their wives to a doctor – it’s considered extremely shameful if anyone, especially a man, puts his hands on your wife. But the Taliban government had banned female doctors from practising. In those circumstances, it was not surprising that since coming back from the mountains, my grandmother’s skills had been in great demand.

I often went with her to attend the births, but it was not something I enjoyed. I would be left to sit outside, helping to look after the family’s children or talking to the woman’s husband. Sometimes, if the family was poor, their house only had one room, so I would be forced to sit in the corner as the woman screamed and bled.

Childbirth horrified me. The labour could go on for hours. I would sit quietly, childishly willing and wishing the woman would get on and push the stupid thing out so we could go home.

My grandmother knew I was squeamish about the whole thing so she teased me mercilessly: ‘Did you see all that blood, Gulwali? Did you look, you naughty child?’

‘No, I did NOT.’

‘Ahhh, you lie to me.’ She’d give me a toothless grin and rub her fingers through my hair.

‘Get off me. You were touching those women.’

That only made her cackle more as she grabbed me in a bear hug, wiping her hands all over my head as I squealed with horror.

Some men would have forbidden her from her midwifery work, especially because it often meant being out on the streets at all hours. But Grandfather was very proud of her and liked to joke about the hundreds of babies she’d ‘given birth’ to.

My family owned various shops in the bazaar, including the tailor’s workshop run by my two middle uncles, and my father’s doctor’s surgery. Along the flat roofs ran a network of vines laden with fat grapes, which we sold commercially. We also had many fields out of town that grew wheat and different vegetables; at busy harvest times, we employed as many as 100 men locally. And before the Taliban took over and banned it, my grandfather had also farmed opium and cannabis – something that was entirely usual for Afghan farmers.

In warm weather, the whole town would become burningly hot, and the brown sandy dust of the town’s desert landscape got everywhere, stinging eyes and blocking noses. My mother and aunts would fight a losing battle to keep it outside the house, seemingly spending all day sweeping with a stiff broom, or banging rugs against the walls to keep them clean. Their efforts were futile. The sand collected in little piles in the corners of the rooms, on door frames, behind chairs, and covered windowsills. And with the dusty sand came all manner of insects and bugs: dangerous scorpions, and the little black ants which, in particular, fascinated me. I loved to watch them mobilize into lines of activity and scurry towards the kitchen. Of course, keeping ants out of the rice stores was another lost battle. Whenever I heard my mother let out a long groan as she opened one of the earthenware containers which kept the grains cool, I chuckled because I knew how funny her angry face would be as she scowled at the infestation of ant invaders in our dinner-to-be.

Aged six, after my grandparents’ nomadic activities were curtailed, I was enrolled in the same local school that my brothers already attended. I literally had to be dragged there on my first day by one of my uncles, as I yelled all the while: ‘I’m not going. I don’t want to go.’ I wanted to go back to the mountains and run with the sheep, not be stuck in a classroom. But I soon settled in and became a very studious, hard-working pupil.

The most fun we had at school was in winter, when we had to fix the roof of our classroom. The building had been badly damaged in the war so none of the rooms had ceilings. In the summer that wasn’t a problem, but in winter each class was dispatched to cut down trees and help drag them back to make a temporary roof. I loved it.

In Afghanistan, children aren’t mollycoddled; they are expected to pitch in and work alongside the adults. Before mosque each morning there were duties in the fields: cutting hay for the cows, watering the crops, harvesting the vegetables, collecting firewood and jerry cans full of water from the nearby well. All the kids went, even the two newest additions to our family, my little sisters, Taja and Razia. As female education was banned by the Taliban government, during the day they helped my mother and aunts with the cooking and cleaning. In our culture, it’s seen as important that girls learn these duties from a very young age, so that by the time they are married they know how to manage the running of a household. They also learned how to sew and embroider, as well as Quranic studies. After those chores, we went to the local mosque to pray, before getting ready for school.

We didn’t really play outside on the street; the kids who played out were seen as the bad kids. My parents thought it showed bad manners and a lazy attitude. So, after walking home from school, my brothers used to hang out in the grape vines, making sure nobody tried to help themselves.

I preferred spending time with the tailor uncles. I was fascinated by the whirr of the sewing machines and the folds of the differently coloured woven cottons and wool they used to make shalwar kameez, the traditional, loose-fitting tunic and trousers worn by Afghan men. At times of celebration, they were overrun with orders, and my uncles would be at the shop day and night sewing wildly to get everything finished. I used to help by cutting out the fabrics and dealing with the customers.

They were very proud of me when I devised my own system of numbering and organization, so that when people came to get their clothes I knew, among the hundreds of garments, where everything was. I took joy in the order and neatness of my system: to me, it was a little world of my own – a way of bringing a sense of order. A long day spent helping them checking off my lists and hanging the clothes ready for the next day was one of my biggest pleasures. By then, I knew I definitely wanted to become a tailor too. I was very enterprising – I even had my own little after-school stall outside their workshop, which sold threads and buttons.

The journey to and from school took us right past my father’s surgery, so occasionally Hazrat, Noor and I would pop in to say hello to him. I used to sweep the floor for him or go and fill a jug with fresh water from the modern pump near the governor’s house. I always felt sorry for him working so hard in his packed surgery, so I wanted to make sure he had fresh, cool water to drink.

In the early mornings, my father would do his rounds in the local hospital. Treating malaria, the mosquito-borne disease which blighted the local area, was his specialism. For the rest of the day he ran his surgery, and people came from miles around for him to treat their ailments.

His surgery was full of strange-looking equipment. I recall a little wooden box which used to store his dentistry tools – I remember watching in horrified fascination as he pulled a patient’s head back and used metal pliers to prise out a rotten tooth. Whether it was stitching a wound, healing a snake or scorpion bite or setting a broken limb, my father’s face was always a mask of studious concentration.

My father’s most precious piece of kit was his microscope, a very rare thing in those days. It was too valuable to leave in the surgery so, at night, he used to carry it home under his arm, covered with a black cloth to keep it free from dust. He was immensely popular, and couldn’t walk through the bazaar without people wanting to shake his hand or offer him gifts of fruit or sweets.

Sometimes, when the surgery was quiet, he used to sit outside in the sun on a wood-framed bench with a seat of knotted string, and chat with his friends or argue about politics. I used to love listening as he and his friends debated the ills of the world and would sit quietly, cross-legged on the ground, taking it all in.

I got the sense that he was a good man, a generous one. He had two big books in his office detailing the people to whom he had loaned money, and he never turned anyone anyway if they needed medicine and couldn’t pay. The ledgers were very big – clearly, a lot of people owed him money.

The most intimate times I spent with my father were during the night, when patients who had walked from outlying villages with a medical emergency banged on our gate, hoping to be seen by him. To treat them he would have to take them to the surgery where his bandages and medicines were stored. In those days, electricity was scarce and only came via a generator, something we limited to using three or four hours a day. As my father helped the patient, I would walk ahead carrying a lantern to help light our path through the darkness. I felt of great consequence as I stepped through the pitch-black streets holding the lamp aloft. It was a source of pride to me to ensure that no one stepped into a puddle or twisted their ankle in a pothole.

One of my most treasured memories was when my grandfather ran away with me. My father had told me off for reasons I can’t remember – I must have done something very naughty indeed, because my father rarely chastised me. My grandfather got really cross with my father, scooped me up into his arms and set off into the mountains.

‘You don’t deserve this boy. He’s coming with me.’

In reality, I was a convenient excuse for the wily old man to get away for a few days. He had wanted to go on a trip to search for lapis lazuli, the blue semi-precious stone that is one of Afghanistan’s most precious natural resources. But he knew that there was no way his sons would approve, so engineering a fight with my father over me had given him a convenient way out.

He and I had a truly wonderful week playing truant and searching for the stones. When we came back, my misdemeanours had been long forgotten – Grandfather was the one in trouble this time.

It was to be my last happy memory before my whole world changed for ever.

CHAPTER TWO

Even before the arrival of the Taliban, my family were religiously and culturally conservative in their outlook. We lived by Pashtunwali – the strict rules every Pashtun must abide by. The codes primarily govern social etiquette, such as how to treat a guest. Courage is a big part of the Pashtun code too, as is loyalty, and honouring your family and your women. No one writes it down for you – there’s no book to learn it from; it’s just a way of life that you are born into, which has remained unchanged for centuries. And, like all Pashtuns, I accepted them unquestioningly. They were – and still are – a source of cultural pride.

The Taliban government also saw it as their duty to keep the peace on the streets. My father told me that before the Taliban came to power, towards the end of the civil war, women and young girls were frequently raped if they went outside, while houses were robbed and children kidnapped and held for ransom. He said the country had been in ruins, but that the Taliban had returned order.

The Taliban position was simple: strong social controls and Sharia law was the true path to both peace and God. To me and the male members of my family this made perfect sense, because it wasn’t really so different from Pashtunwali.

No one asked the women for their views, however – they didn’t get to have a say in these kinds of political matters. But I think the whole family was in unity. We all understood our different roles within the household.

I was aware that not everyone agreed with this, however. A very few of my friends at school told me their parents feared the Taliban and thought they were bad people. They said they were taking our country in the wrong direction and preventing development. They also said that they abused women.

When I heard this, it made me angry. My uncle, Lala, was a very senior Taliban, so how could they possibly be bad? And yet their rules certainly were strict – men’s beards had to be a certain length and they had to wear traditional, baggy clothes at all times, while women had to wear the burqa so their faces couldn’t be seen, and soft-soled shoes so they couldn’t be heard. In addition, you had to pray at fixed times of the day, and if you were seen on the streets or caught working when you should be praying, it was deemed a crime.

Fridays are the main day of prayer in Islam. When the mosque loudspeakers blasted out the hauntingly beautiful call to prayer, everyone in the whole town would stop whatever they were doing and go straight to mosque. The Taliban had a special team, called the Vice and Virtue Committee, who made sure everyone obeyed. They wore black turbans and patrolled the streets in four-wheel drives, pulling over and leaping out of the vehicle if they saw something amiss.

One sunny Monday afternoon we were in the tailor shop when we heard a big commotion outside. A man stuck his head through the shop door, his face ablaze with excitement: ‘Come on. Twenty lashes.’

My uncles quickly locked up the shop and urged me to follow them to the bazaar. A large crowd had already gathered at the scene: two men in black turbans stood over a kneeling man, who was naked from the waist up.

‘Speak. Admit your crime,’ said one of the turbans.

The man said nothing.

‘Speak.’ The turban smacked the back of the man’s head.

‘I—’

‘Louder.’

The man mumbled something, but it was impossible to hear it over the hum of the crowd.

The turban turned to the crowd with a smirk. ‘This man did not attend prayer on Friday. He was found inside his home.’

The crowd jeered at this seemingly obscene crime.

‘Do you have an excuse?’

This time the man looked up and spoke loudly. ‘My wife was sick. I couldn’t leave her. I thought she was dying.’

At this, both turbans roared with laughter. The crowd followed suit.

The second turban spoke this time, his voice ringing out as clear as a bell: ‘The Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan gives the sentence of twenty lashes with justice to this man for his crime. May this sentence be an example for anyone else thinking of committing such a crime. Anyone who goes beyond the limits of God’s law and against His rules, let it be known this will be their fate.’

He lifted a thin reed high into the air.

‘By Allah the most merciful, you have been sentenced to a fitting punishment for your crime.’

As he brought the reed down on the man’s back with a loud swish, the crowd roared and cheered.

The turban hit the man again and again and again.

By the time it was over, their victim had crumpled into a heap, his back a bloody mess. I don’t know if anyone helped him or if they took him to prison after that, because my two uncles said it was time to get back to the shop.

Five minutes later, the sewing machines whirred into life and I was back to hanging clothes as if nothing had happened.

Many times after that I saw people get lashed. I once saw an old man beaten with a wire cable because his beard was too short: the black turbans would grab a beard with their hands to measure it – if the person measuring it had big hands and you had a wispy beard, then it was unlucky for you. Other times they gave out smaller punishments, such as painting someone’s face black and marching them around, encouraging people to abuse them.

I suppose it sounds shocking, but this was all I knew. I had been taught by Uncle Lala that the Taliban only punished someone when they broke the law, so in my child’s mind if someone was suffering this way they must have deserved it.

But one incident will always haunt me.

Grandfather and I were with a friend of his on our way to visit some relatives in a different district. We had stopped for chai, tea, in a small town. As we sat outside the tearoom, we watched several men begin walking and running in one direction. My grandfather stopped a man to ask what was happening.

‘Justice, my friend. Justice.’

Curious to see what was happening, we followed. At the edge of the village, scores of men had gathered in a large clearing. Some of them were shouting, ‘Allah akbhar. Praise be to God,’ while others were whooping with joy.

At first I thought it must be some kind of sporting event – maybe a dog- or cock-fight. I strained my head to see what they were looking at, and my grandfather’s friend lifted me on to his shoulders.

I saw a woman. She was covered in a burqa with a black blindfold tied around her eyes. Her hands were tied behind her back with rope.

A man next to her – I guessed a Taliban official from the Justice Department – raised his hand. The crowd went silent. ‘This woman is a dirty woman. She is an adulteress, a whore.’

The crowd roared insults at her.

‘The Islamic Emirates of Afghanistan gives the sentence of death to this woman for her crime. May this sentence be an example. She has been condemned to death by stoning. Let it begin.’

At that, he placed his hand on the woman’s shoulder, almost tenderly, and walked her towards a dug-out area of earth. He took her arm and helped her get into it, so that she was standing in it, up to her waist. She didn’t try to resist.

It was then that I noticed the rocks, sitting in a pile to the front of the crowd.

The Talib walked to the pile and picked up a large stone. He waved it above his head like a trophy. ‘By Allah the most merciful, you have been sentenced to a fitting punishment for your crime.’

He walked back towards her, until he was a couple of feet away.

Then he threw the stone hard, so that it smashed against her head.

The crowd went wild. All at once men began picking up the rocks and throwing them at the woman. At first, she didn’t seem to move, even as they hit her, but then one little rock caught the back of her head sharply, and she began to try to wriggle her way out of the pit. But as she did so, another hail of stones and rocks caught her and she fell backwards. After that, it was a bit of a blur for me, just a hail of rocks and a lot of shouting.

The whole thing only took a couple of minutes.

I don’t think I really understood what I was seeing. The noise, the excitement of the crowd, the calm silence of my grandfather and his friend – I didn’t enjoy it, but I didn’t cry either. As I sat on the shoulders of Grandpa’s friend, I looked around and saw other boys my age on shoulders too. Their expressions were blank but their eyes were confused, mirroring my own.

With hindsight, I can see what barbarity this was. But it has to be put into context. The country was recovering from a war in which brutality had known no bounds. Millions of people had been killed, thousands of women raped and children slaughtered. There had been a complete breakdown of law and order with no national governance. Their mantra was this: ‘If you don’t accept peace or our rules, we will force it on you.’

My grandfather called life under the Taliban: ‘The best of times we are living in.’ Given that he’d lived most of his life in the insanity of war, I don’t think it is too surprising that he and many other Afghans felt this way.

But, as is ever the case in the geopolitics of my country, we were about to get out of the frying pan and into the fire.

CHAPTER THREE

I was seven years old.

I remember running between the kitchen and the guest house, my mother handing me pots of tea to take to the assorted tribal elders and Taliban fighters who had amassed in our home. The air was thick with tension and heavy with discussion.

‘We didn’t have anything to do with it, so why should we bow down to the imperialists?’

‘Bin Laden is our guest. Pashtunwali must prevail.’

‘Our great country will never cede to this pressure.’

A Saudi man called Bin Laden, who Uncle Lala told me was a great freedom fighter, had attacked America. TV was banned under the Taliban so we didn’t see any images of it, but the radio had been broadcasting non-stop news about it. Thousands of people had died in the attacks. They said people had been jumping from windows to escape. I had been told that Americans were infidels who didn’t follow Islam but as I listened to these stories, I felt sad at the news and thinking about the families of the people who had died. Given my family history of living in refugee camps, I think I had an innate understanding that, wherever they were from, all people suffered in war and conflict.

Now, just days after the attack, the US was angry with Afghanistan, blaming us for it. This was because the Taliban were refusing to bow to American pressure and hand over Bin Laden, who was said to be sheltering in Tora Bora, a place only a couple of hours’ drive away from where we lived. The US had threatened to attack if they didn’t hand him over, but the Taliban refused because, under the rules of Pashtunwali, he was our guest, and a guest is under the protection of the host.

There was a swell of patriotism. No one really believed America’s threats, mostly because everyone knew the Taliban had had nothing to do with the attack themselves, and we assumed the Americans accepted that too.

But, it turned out, this wasn’t a view shared or understood by the world. Within days the US, supported by European countries, had invaded my country, and the Taliban began to retreat.

When it started, we could see US fighter jets overhead. For a day or so they only circled the skies, not doing anything. Taliban troops were everywhere, and lots of local people were volunteering to fight with them.

My father was expecting the worst and was busy trying to amass extra medical supplies. He had also ordered my mother to pack bags and food and prepare to take us children to the shelter of a nearby bunker. There were several concrete bunkers on the outskirts of town, a legacy of the civil war.

The following day, the US began to bomb Tora Bora. We could hear the sound but it was far enough away for us not to be at direct risk. Within days, however, bombs rained from the sky directly overhead.

It was terrifying.

It was never clear exactly where the planes would come from. We would hear the screech of Taliban anti-aircraft missiles attacking them as they approached, then there would be the sound of deafening, terrifying explosions. The whole ground used to shake with the force of the bombing. After each bombardment we would come outside for air and look up at the trails of smoke the B52 bombers left behind in the sky.

Pretty much every type of bomb except nuclear bombs rained down on my country. Even today, children are born with diseases and deformities caused by the toxic effects of that time, something that makes me very angry.

The children and aunts huddled in the bomb shelter with other families. Uncle Lala was the regional commander for the Taliban, leading the fight against the invaders. My father stayed in the hospital, treating the hundreds of wounded. My grandfather insisted on staying in the house to stop it being looted. I was proud of them all, for different reasons, but I was most worried about my father. I feared the bombs might hit the hospital.

I longed to run to the solace of my mountain paradise, but it wasn’t safe. Fighting echoed across the hills. It seemed the whole of Afghanistan was under attack, and for days we couldn’t sleep. I thought it was only a matter of time before our bunker hiding place was discovered.

I expected to die at any moment.

It was only later that I learned that the area around our home had been the last frontline; Uncle Lala had been one of the last local commanders of the Taliban to hold his position against the US-led coalition forces. We were told that his courage allowed busloads of fighters to escape Kabul into neighbouring Pakistan; in my childish eyes, this made him something of a hero. Soon after that final battle, he fled the country himself, and we didn’t know where he had gone. I feared he’d been caught and killed, but we had no way of knowing.

For us, life then began under occupation. Suddenly, US troops were everywhere, convoys of armoured vehicles speeding down the road. The first time I saw Western troops on the ground, I was so scared of their big guns. They looked like something from another planet. From a safe distance, my brothers and I would throw stones at them.

After a while, seeing them became normal.

The pressure and political turmoil impacted on all of us. My father took the decision for the family to leave the district and go back to the neighbouring district where he had been born. Things were slightly safer there.