Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The pub has been at the heart of English life for centuries, evolving from elegant coaching houses and humble alehouses through Victorian backstreet beerhouses and 'fine, flaring' gin palaces to the drinking establishments of the twenty-first century. In this new and revised edition, historian Paul Jennings takes us on a fascinating journey over three centuries of pub life. Set within the wider context of social change, Jennings delves into the lives of the customers who frequented them, as well as those of the men and women who ran them, and takes a closer look at their architecture and interior design. The Local has been brought up to date to record both the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic on English pubs and what it tells us about pubs' continuing importance to English people.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 464

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Felicity

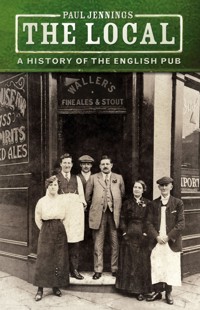

Cover illustration: Mine hosts and staff outside the Black Swan in Thornton Road, Bradford, c.1915. From left to right are barmaid, barman and waiter, landlord Arthur Gray, landlady Sarah and a neighbouring shopkeeper. (Author)

First published 2007

This edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Paul Jennings, 2007, 2011, 2021

The right of Paul Jennings to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9783 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

About the Author

Prefaces and Acknowledgements

1 Introduction: What is a Pub?

2 The Evolution of the Public House 1700 –1830

3 The Public House and Society 1700 –1830

4 Free Trade in Beer 1830 –1869

5 The Licensed Trade 1830 –1869

6 Running a Pub

7 Customers and their World

8 Policing the Pub

9 Politics and the Pub

10 The First World War and the Pub

11 Improved Pubs and Locals 1920 –1960

12 Conclusion: Modern Times

Reference Notes

Note on Sources and Further Reading

About the Author

Paul Jennings taught history for thirty years in university adult education, during which time he has written, lectured and broadcast on the pub and the broader history of drink. He has written several books and articles, including A History of Drink and the English, 1500–2000 (Routledge, 2016). Born and brought up in Bradford, where he also later worked, he now lives in Harrogate with Felicity and their sons Albert and Frank.

Prefaces and Acknowledgements

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

The years since the publication of the revised paperback edition of this book in 2011 continued to be difficult for the pub. The start of 2020 then brought a massive challenge to the institution with the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s response to it. Once again, the fate of the pub, coupled with assertions of its vital importance to the national life, was the subject of intense public interest and discussion. In these discussions I have shared, although sadly not in pubs, having visited only one in the year from March 2020. The implications of the response to the pandemic will undoubtedly be felt for years to come in ways that no historian would be rash enough to attempt to predict. For this third edition, I have revisited my conclusions of 2010 in the light of the decade’s developments; I have not provided a detailed history of the pandemic. I have also made minor corrections and amendments to the text and updated the section on sources and further reading. I thank Rebecca Newton of The History Press for supporting this new edition.

Harrogate, March 2021

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

The three years since this book was published have been difficult times indeed for the pub. By mid-2009 the trade body, the British Beer and Pub Association, was reporting the closure of some fifty-two pubs every week throughout the United Kingdom. In total, in the three years 2007–2009, getting on for 6,000 ceased trading. Many reasons have been put forward for this: the recession, rising costs, the price of beer, cheaper supermarket drink, the policies of pub companies and the 2007 smoking ban among them. But the decline of the pub in the national life is a phenomenon of long standing, based in a great variety of economic, social and cultural changes; and yet at the same time it remains a vital institution in that life. For these two reasons an understanding of its history is essential, which this book seeks to provide. For this paperback reprint I have made a small number of minor corrections and revisions and updated the Note on Sources. Thanks also finally to Jo de Vries at The History Press.

Harrogate, September 2010

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

This book is the product of over twenty years of researching and thinking about the history of the pub and drink. The greater part of that work has inevitably been in libraries and archives. But it has been informed too by my observations working in a pub for some years in the Lake District and helping out in an Irish bar on New York’s Eighth Avenue, as well as from a customer’s point of view. Those observations may have taken in some depressing places and some dispiriting behaviour, but the pub has also provided me with real pleasure. I recall fondly, for example, the Castle Hotel in Oldham Street, Manchester, the Albert Hotel in Keighley or the Princess Louise in Holborn, three very different establishments. It is this protean institution that I have sought to portray. I have approached it in a scholarly way, but I have also tried to write for a wider readership interested in this essential part of the country’s history.

Over the years of research I have incurred many debts. More particularly for this book I should like to thank the staff of the J.B. Priestley Library of the University of Bradford; the Brotherton Library of the University of Leeds; the Local Studies Library at Bradford Central Library; the Bradford and Wakefield branches of the West Yorkshire Archive Service; the East Riding Archives at Beverley; the North Yorkshire Record Office at Northallerton; the Lancashire Record Office at Preston; and Southampton Archive Services. For photographic assistance I should like to thank James Smith, and for drawing the map and plans of pub interiors William Sutherland RIBA. I thank David Gutzke for the copy of his unpublished paper on women publicans. Students on my Drink and Society course at the University of Bradford have offered many useful thoughts on the subject. For commenting on all or part of the work in progress I thank John Chartres, David Fahey, Louise Jackson, Pete Rushton, Dave Russell, George Sheeran and Andrew Whittingham. Any errors or shortcomings in the book are of course entirely my responsibility. Thanks also to Sophie Bradshaw and Lisa Mitchell at Tempus.

Harrogate, February 2007

1

Introduction: What is a Pub?

What is a pub? For George Orwell the perfect pub, embodied in the mythical Moon Under Water, was a place whose ‘whole architecture and fittings are uncompromisingly Victorian’. As he evoked it: ‘The grained woodwork, the ornamental mirrors behind the bar, the cast-iron fireplaces, the florid ceiling stained dark yellow by tobacco-smoke, the stuffed bull’s head over the mantelpiece – everything has the solid comfortable ugliness of the nineteenth century.’1 The essence of the pub was similarly located in the Victorian period in a trio of books published either side of the Second World War: Maurice Gorham’s The Local and Back to the Local and, written with H. McG. Dunnett, Inside the Pub. In the latter work it became the ‘English pub tradition’, having evolved through the centuries to be a living art form. It comprised both the ‘plain interior with modest embellishments’ in the pubs of villages and country towns and the ‘fantastic, exotic scene’ of the urban saloon or gin palace.2 To the question – what is a pub – this became a common response in the post-war years, as the country experienced the quickening changes of a more affluent society. For architectural historian Mark Girouard, writing in the early 1970s, Victorian pubs had ‘been much and rightly admired’ and it was their ‘splendours’ which he wished to document before the ‘tiny fragment’ which survived was itself lost. Christopher Hutt, later national chairman of the Campaign for Real Ale, fearing at that time the death of the English pub, looked more to the plainer interior in bemoaning the impact of modernisation. For him: ‘Luxurious soft furnishings replace the wooden seats, wall-to-wall carpeting covers those worn-out old tiles, the ornate mirror and the dart-board make way for a set of tasteful hunting prints.’3 For all these writers the Victorian pub was a thing to treasure: it was the pub.

Yet for other writers, like Thomas Burke, with several works on the subject in the 1920s and 1930s, this pub was an ‘uncouth thing’, as pub was an ‘uncouth word’. For him the gin palace was a ‘flaring, roaring, gilt-and-plate glass abomination’, a standardised thing, devoid of individuality. For him, as for many others, it was the inn and the old-fashioned tavern, as they had developed into the early nineteenth century, which were the true geniuses of the public house. Thus for A.E. Richardson, who published in 1934 The Old Inns of England, Victoria’s reign, far from being the quintessence of the pub, witnessed ‘a long eclipse of the tradition of innkeeping in this country, and wherever the germ of the new industrialism developed, the old houses were generally replaced by the reeking, flaring gin-palaces of the nineteenth century’. Theirs is a Dickensian vision, as it greeted Pickwick at the Saracen’s Head in the old innkeeping town of Towcester:

The candles were brought, the fire was stirred up, and a fresh log of wood thrown on. In ten minutes’ time a waiter was laying the cloth for dinner, the curtains were drawn, the fire was blazing brightly, and every thing looked (as every thing always does in all decent English inns) as if the travellers had been expected and their comforts prepared, for days beforehand.4

It was this ideal of the hospitality of the traditional inn, which drew those from the end of the nineteenth century and through the inter-war years who wished to ‘improve’ the pub’s Victorian debasement. Architect Basil Oliver in this way looked to the Renaissance of the English Public House transforming ‘the blatant vulgarity of the declining Gin Palace’ or the ‘evil-smelling fly-infested Victorian “pub”’ into ‘their clean wholesome successors of today’.5

Whether writing of the inn or the pub, three shared themes stand out in works such as these. One is of a sense of loss. The Victorians felt it, surveying the massive changes of their times, and the old inns and the coaching days were a favourite subject of local antiquarians. A typical example is William Scruton, devoting to it a chapter of his characteristically titled Pen and Pencil Pictures of Old Bradford, published in 1890. As he put it: ‘In contrasting the old hostelries of Bradford of fifty years ago, with the dramshops of to-day, it is impossible to resist a feeling of regret at the change which has been brought about.’ It was not in the gin palace that ‘good-fellowship’ was to be found, or rest and refreshment for the traveller. As he put it: ‘Truly, the “march of civilisation” has not in this respect, brought with it an improvement on the past.’6 The equally marked changes of the twentieth century evoked a similar response. As Maurice Gorham expressed it in his aptly titled chapter ‘Obituary’ as he went Back to the Local in 1949: ‘For those of us who feel sad whenever a pub vanishes, this is a sad life. Progress, reconstruction, town-planning, war, all have one thing in common: the pubs go down before them like poppies under the scythe.’ He even experienced his own Dickensian moment:

I grieved particularly for the White Hart in Lexington Street, for it was a little quiet neglected house, with the door swinging on a strap and a step down to the bar, where I always felt that Bill Sikes might at any moment spring up from the deal tables with his white dog at his heels.7

As urban redevelopment really got under way from the late 1950s, similar sentiments were expressed. When the Victorian Society’s Birmingham Group surveyed the city’s Victorian pubs in the mid-1970s, for example, it found that the highway engineers and the planners had between them destroyed ‘many good pubs’. And what they had missed, interior designers were then transforming out of all recognition. Looking back at the survey and subsequent developments in a 1983 publication by SAVE Britain’s Heritage and the Campaign for Real Ale, Alan Crawford put it: ‘The Victorians had a secret of good pub design which has somehow got lost.’8 The theme of loss intensified across the new millennium with the seemingly relentless closure of pubs. A three-part BBC documentary, whose making was interrupted by COVID-19, stated this bluntly in its title: ‘Saving Britain’s Pubs …’

To the theme of loss we may add that of Englishness. Thomas Burke began his volume by declaring that: ‘To write of the English inn is almost to write of England itself … as familiar in the national consciousness as the oak and the ash and the village green and the church spire.’ Expressing unchanged sentiments half a century later, a popular portrait of The English Pub observed: ‘The pub is an institution unique to England, and there is nothing more English.’9 But just as the inn was linked to that Englishness felt to be embodied in the past and the rural, so here the urban pub was also seen as expressive of the national genius. Thus a 1928 essay on the London public house found its Englishness in the domesticity of its welcome, the solidity of its architecture and the happiness and contentment of its customers. But the pub was more than just an expression of those qualities, it was ‘the true temple of the English genius’ – the poetic spirit so essentially a part of the English character.10

The third theme has been the idea of the pub as the hub of the community – the local. Although pubs had served this function for centuries, as an idea this too was articulated during the inter-war years as a variety of social, cultural and economic changes affected the pub. It was confirmed by the vital role which the pub played as a social centre during the Second World War. But in the post-war period it has remained central to ideas of what the pub is. This is true for those who fear the pub’s decline. Thus the CAMRA newspaper What’s Brewing headlined its ‘Pub in 2000’ conference as: ‘The battle is on to save Britain’s locals.’ But it is shared too by the industry. Pub company Punch Taverns, with over 9,200 pubs across the United Kingdom by 2006, categorised this ‘portfolio’ under nine headings, four of which used the term as in basic, mid market, city and upmarket locals.11 And of course with the Rovers Return, the Queen Victoria and the Woolpack, the nation’s popular soap operas have placed a local at their very centre.

The public house has thus occupied a central place in the nation’s imagination, expressing its very identity. It is worth exploring its history for that reason alone. But clearly not everyone has had in mind the same thing. This in turn reflects the reality that we are looking at an extremely heterogeneous institution. For when we speak of the ‘pub’, we are speaking of something which only became generally known by that name quite late in the nineteenth century. Into its creation went a great variety of drinking places – inns, taverns, alehouses, gin shops, beerhouses and others. And even as ‘pub’ became finally commonly applied to them, it still covered an astonishing variety of establishments, from city gin palaces to basic back-street boozers, from railway hotels to rural inns. And more than that, it is possible to see each pub as possessing its own individuality, formed from its architecture and interior design, the types of drink and sometimes food on offer, the publican and his staff and the varied mix of customers and their favoured pursuits. As Mass Observation replied at the end of the 1930s, in its detailed and invaluable study of the pub, in answer to the question – what is a pub – no typical pub in fact existed.12

Charting the history of the pub then is a complex task. It is an institution which has always been evolving. Moreover, it has done so in response to changes in the wider society and its development cannot be understood without reference to them. The subject demands to be approached from a variety of perspectives: economic, social, cultural, political, legal and architectural. Further, its study is inseparable from the history of the consumption of alcohol, upon which other perspectives have also been utilised, such as those from anthropology and psychology. In my approach to the subject I have tried to learn from all of them. I have also been mindful of attempts to present more overarching interpretations of drinking or of drinking places. In relation to the latter, one strand of explanation has been to link the modern drinking establishment to the emergence of capitalist society in, for example, its increasing demarcation of the dividing line between the worlds of work and play inherent in the capitalist work ethic.13 Another has been to bring a feminist perspective ‘to construct a view of the gender relations of pubs’ and portray it as a ‘male domain of recreational public drinking’, enjoyed at the expense of women. As Germaine Greer expressed it in The Female Eunuch: ‘Women don’t nip down to the local.’14 How that world of male domination has changed will be another area to be explored.

My approach has also been informed by looking at the experience of other countries. If the pub is so English, what is it about English society which has produced it and the way people use it, in contrast to say the French café or the American saloon? Within the British Isles too Ireland and Scotland have had contrasting drink histories and their pubs were quite distinct from their English counterparts.15 Whilst I focus on the English experience, I am also mindful of the importance of local and regional variation within the country. This is true, for example, of the very basic question of the numbers of pubs in relation to population, with marked differences between towns, or of the nature of pubs in so many differing communities: rural, dockland, mining and so on.

In writing this history I am drawing upon the work of many scholars. But it is also the product of my own researches in a wide range of sources, some of which were written up in my earlier case study of the pub in the northern industrial city of Bradford.16 It is also, inevitably, provisional. There are many questions which merit further study and I hope at least that I have provided a helpful framework for future work on the subject. The book’s succeeding chapters are structured as follows. Beginning in the late seventeenth century, when the term ‘public house’ comes into use, I chart in chapters two to five the evolution of England’s varied drinking places up to the 1860s. It is at this point that the ‘pub’ as a recognised entity emerges. Chapters six to nine then focus on the pub in what we might loosely think of as its Victorian heyday. They look at the institution itself in all its aspects – buildings, publicans and customers, at the question of how society sought to police it and at how it was subject to a variety of political pressures. The next two chapters then take in the important effects of the First World War, the story of the pub in the inter-war years and the experience of another war. The final chapter concludes with a survey of later twentieth- and early twenty-first century developments to the COVID-19 pandemic and an assessment of the place of the pub in the contemporary national life.

2

The Evolution of the Public House 1700 –1830

Historically, there were three main types of establishment for the sale of alcoholic drink: the inn, tavern and alehouse. All three dated back to the medieval period and were the designations used in a government survey of 1577, which provides the first detailed information we have on drinking places.1 The term ‘public house’ only came into general use in the late seventeenth century. Its precise origin is unclear, but it seems likely that it derived simply from a contraction of ‘public alehouse’, as this form was also employed.2 The use of public house was, however, not confined to alehouses. Celia Fiennes, touring the country in 1697, was disappointed not to find accommodation – an essential inn service – at a ‘Publick house’ at Brandesburton in the East Riding of Yorkshire, ‘it being a sad poore thatch’d place and only 2 or 3 sorry Ale-houses’.3 The term was also used at this time in a statute requiring standard measures for the sale of ale and beer addressed to innkeepers, alehouse keepers, victuallers and keepers of any ‘publick house’.4 Similarly, in the 1720s Daniel Defoe distinguished ‘inns and publick-houses’, but also paired ‘inns, and ale-houses’ under a more general description of ‘publick houses of any sort’.5 The term, it would seem, was thus used in an overlapping way for inns and more substantial alehouses, and in an inclusive way to cover all types of establishment.

The use of public house in those ways certainly increased over the course of the eighteenth century. This is clear, for example, from the numerous references in newspapers, the production of which expanded greatly in this period. It is also possible to chart its usage over time in the published proceedings of trials at the Old Bailey, which contain hundreds of references to drinking places.6 Whilst both sources show public house coming into general use, the older forms continued to be employed. The diaries of John Byng (later Viscount Torrington), which record his travels throughout England and Wales in the 1780s and 1790s, clearly illustrate both this and the overlapping nature of usage. He refers to the same establishment alternately as an inn or public house, but he also does the same with alehouse in describing, for example, the George at Market Harborough as an ‘alehouse inn’. Although this might seem on the face of it to be terminologically confusing, in Byng’s mind it clearly corresponds to a hierarchy of establishments. Thus, in his typically acerbic way, he opines that ‘the best Cambridge inn wou’d form but a bad Oxford alehouse’, or that at Stafford: ‘All the inns … are merely alehouses.’7 To begin our survey then, it makes sense to introduce the three original types: inn, tavern and alehouse, before examining in more detail the nature of this hierarchy.

The inn was defined, both in everyday practice and in law, by its primary purpose: the service of travellers. For this reason inns were not included in the legislation of 1552 which required alehouses to be licensed by magistrates. The fact, however, that they too sold ale led to its being extended to them.8 This did not remove the distinction between the two types. The position was summed up in the following way by the authoritative guide for eighteenth-century magistrates: ‘Every inn is not an alehouse, nor every alehouse an inn: but if an inn uses common selling of ale, it is then also an alehouse; and if an alehouse lodges and entertains travellers, it is also an inn.’9 Upon innkeepers the law placed obligations to receive travellers and to safeguard their goods; failure so to do made them liable for damages.10 Performing these functions, inns developed during the later Middle Ages, gradually replacing the hospitality provided for the growing numbers of travellers at monasteries or in the houses of the nobility. By 1577, an estimate based on the survey of that year suggests there were around 3,600 inns. This total in turn may more or less have doubled, to between 6,000 and 7,000 inns, by the close of the seventeenth century.11 At that date, for the nineteenth-century historian Thomas Babington Macaulay in his famous survey of the social scene, ‘England abounded with excellent inns of every rank’.12 A more mixed picture is conveyed by travellers’ tales, as they will. Samuel Pepys, for example, at the George, Salisbury, on the way to Bristol in June 1668, enjoyed the ‘silk bed and very good diet’, but complained about the horses provided and later bemoaned ‘the reckoning which was so exorbitant’. Later on the journey, at a little inn at Chitterne, he reports the beds were good but ‘we lousy’.13 Although standards clearly might vary, there is no doubt that inns were essential for travellers.

The tavern also dated back to the Middle Ages as a specialist establishment for the sale of wine.14 Its distinctive role was recognised in statute in 1553 when the sale of wine was restricted to a permitted number of taverns in specified towns. Although this law appears to have been limited in its effect, since the survey of 1577 reported more than the permitted numbers, the separate administration of wine licensing was maintained: they were either granted by the Crown or enjoyed as a right by freemen of the London Vintners’ Company.15 At the close of the seventeenth century they retained their specialised function as generally rather more upmarket purveyors of wine and food. Pepys was a great frequenter of taverns. In April 1663 we find him enjoying ‘Ho Bryan’ at the Royal Oak Tavern in Lombard Street, and in February 1668 at the Bear Tavern in Drury Lane, ‘an excellent ordinary after the French manner’, that is with the courses served separately. Once again, however, standards varied. At the Three Cranes Tavern, Old Bailey, in January 1662, in the ‘best’ room of the house, a wedding party found itself crammed, according to Pepys, ‘in such a narrow dogghole … that it made me loathe my company and victuals; and a sorry poor dinner it was too’.16 The Three Cranes was a tavern of long standing, deriving its name, it has been suggested, from the three lifting cranes which unloaded casks of wine from boats into the warehouse of the Vintners’ Company above London Bridge. It was usually represented pictorially on its sign by the feathered variety.17 Although it is not possible to give a national figure for taverns, London, with its far greater concentration of people and wealth, undoubtedly had the most. A survey by William Maitland in the 1730s gave a figure of 447 taverns, compared with 207 inns.18

Vastly outnumbering inns and taverns were the alehouses. They were common by the early fourteenth century in town and country. Based on the survey of 1577, estimates of between 20,000 and 24,000 alehouses for the country as a whole have been made.19 From 1552 they required a licence from the magistracy. This also extended to what were called tipling (or tippling) houses. Although the Act itself does not clarify what distinguished the two, and in practice they may have been synonymous, it seems likely that tiplers simply sold drink. In 1594 the tiplers of York were reminded by the city’s corporation that they were not allowed to brew. Similarly, at a licensing session in the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1723 the tiplers were distinguished from the brewsters. In any event, except in the archaic language of the licensing system, where it was still in use, for example, in 1786 in the East Riding, the term as applied to a drinking place had largely disappeared by the beginning of the eighteenth century. It did continue to be used to denote prolonged or habitual drinking, again to be found in statute, and for much longer of course as ‘tipple’ – a generic term for strong drink.20

Arriving at a total of alehouses at the close of the seventeenth century is not easy. Contemporary estimates exist, but the only precise figures we have are Excise statistics of those victuallers who brewed their own beer, which includes innkeepers and of course excludes all those supplied by common brewers, brewing that is for general sale. Over the period 1700 to 1704, there were on average per year nearly 44,000 brewing victuallers. Based on an estimate that one-third of the alehouse keepers did not brew their own beer, Peter Clark suggests a total figure of as many as 58,000 alehouses. This works out at one for every 90 of the country’s inhabitants, which is comparable with the figure Maitland gave for the capital in the 1730s of 5,975 alehouses, or one for every 100 of its citizens.21 These thousands of alehouses had developed as the basic, everyday social drinking place of the lower orders. By the later seventeenth century, however, many of them were aspiring to greater respectability and in this way making the transition to public house.22 Thus we find Pepys also frequenting alehouses, for example with his wife, or with companions enjoying music from harp and violin. But there were clearly for him degrees of alehouse. He noted of the Gridiron in September 1661: ‘the little blind alehouse in Shoe Lane … a place I am ashamed to be seen to go into.’ And the previous November necessity clearly drove him: ‘being very much troubled with a sudden loosenesse, I went into a little alehouse at the end of Ratcliffe and did give a groat for a pot of ale and there I did shit.’23

We thus return to my suggestion of a hierarchy of drinking places. There were distinct types, but there was also overlap between those types and differentiation within them. Further, the types themselves, the element of overlap and the differentiation were all in turn subject to change through the eighteenth and into the nineteenth centuries. At the top of this hierarchy were the great inns of England’s major towns, whose dominating presence and imposing exteriors were often remarked upon by contemporaries. Defoe noted that Doncaster, on the Great North Road, was ‘very full of great Inns’, or that the George at Northampton looked ‘more like a Palace than an Inn’. Based on this and similar comments, and on the evidence of the building and rebuilding of inns, Peter Borsay characterised them as ‘the true palazzi of the English Augustan town’, key features of an urban Renaissance.24 Building and rebuilding went on throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although it is impossible to give precise overall figures for the process, numerous individual examples might be given. I will take just two from Yorkshire, early and later in the period. In Ripon, a cathedral and market town boasting, Defoe thought, ‘the finest and most beautiful square that is to be seen of its kind in England’, the Unicorn, which dated back at least to the early seventeenth century, was rebuilt and extended to the rear in the mid-1740s. In the town’s Georgian transformation a number of other inns were also opened or rebuilt. At Beverley, the county town of the East Riding, the Blue Bell was rebuilt in 1794, raising it from two to three storeys, adorned with portico and balcony and renamed more grandly the Beverley Arms.25

The Beverley Arms later also adopted the title of ‘hotel’. The use of that term would seem to date from the late 1760s, adopting for added distinction a French word that covered mansions as well as inns. The huge York House Hotel was built at Bath at this time and became its premier establishment. The first landlord of the Hotel at Exeter, which opened in about 1770, Peter Berlon, was himself of French origin. Of the ‘new hotel’ in Birmingham, John Byng expressed himself ‘much pleased with our entertainment’, contrasting it with ‘the bad inns in the old town’. A nice example, finally, of the overlapping and changing use of names comes from Margate, with an advertisement of 1775 for the New Inn, Tavern and Hotel.26 The use of hotel to designate larger establishments particularly devoted to the provision of accommodation gradually became more common. In the Yorkshire spa town of Harrogate, as in other watering or seaside places, we find by the 1820s its adoption by older inns, like the Crown, Dragon, Granby, Queen’s Head or White Hart Hotels, and its use with the proprietor’s name, as at Gascoigne’s or Hattersley’s Hotels. Even as late as this it perhaps retained some novelty, as one still finds places called simply the Hotel, like the one kept by Sarah Greaves in Briggate, Leeds, although the commercial directory which listed it did so under a heading of Hotels, Inns, Taverns and Public Houses.27

In addition to this process of building new inns and rebuilding or improving old ones, alehouses were also being upgraded to perform more inn functions. One estimate puts the number of such upgrades over this period at perhaps seven to ten thousand.28 Licensing magistrates began to insist on the provision of stabling and suitable lodgings, and more generally the improvement in housing and the rising expectations of customers worked to effect this change. Evidence from a sample of probate inventories covering Kent, London and Leicestershire from 1660 to 1750 suggests a significant advance in the number of rooms compared with the first half of the seventeenth century. The valuations of properties after fires provide further support for this. Eight alehouses destroyed at Blandford Forum, Dorset in 1731 were valued at £134 each. Whilst some were small, like the little thatched house just four and a half yards square worth £36, the majority were more substantial. The Black Horse, part thatched and part tiled, with a ground area of ten square yards plus stable and brewhouse, was worth in all £205.29 Later evidence confirms alike the improvement and the hierarchy of establishments. Looking at the West Riding market and textile town of Bradford, a rate book of 1805 lists twenty-six inns and public houses, of which the seven principal inns were of an annual value of £40 or over, forming one quarter of all property in the town so valued. Over half had a value of £20 or above, with just five smaller houses valued at between £5 and £9. A much larger database of policy values for 2,295 publicans from the 1770s and 1780s, derived from the Sun and Royal Exchange insurance companies, shows an enormous range of values. Around half of the businesses lay in the range £100–500, but 20 per cent reached £1,000 or more. Those in the top quartile ranked alongside medium-sized cotton or worsted spinning mills. This, according to John Chartres, who compiled the database, placed ‘innkeeping pretty high in the business hierarchy of the later eighteenth century’.30

We can see the hierarchy too when we look at the design and internal layout of inns and public houses. Looking at the larger inns first, two types of plan have been identified, both in use from its medieval origins. There was the courtyard plan in which the central yard was enclosed by two or more storeys of public and private rooms, sometimes galleried to give independent access to them. This plan was dominant in London, economising as it did on space on the major thoroughfares, with great inns like the Bull and Mouth (Figure 1) or the Belle Sauvage striking exemplars, but was found too in provincial towns, as at the New Inn at Gloucester.31 More numerous, however, was the block, or gatehouse, plan in which the main rooms were to the front facing the street and the yard was to the rear, often accessed from a lane behind the inn in addition to the entrance from the street. The innkeeping town of Stony Stratford, on the London to Chester road in Buckinghamshire, had several designed this way along its High Street, with long yards to the parallel back lane.32

Apart from the distinctive galleried inns, however, there was little to distinguish the inn or public house from ordinary houses of similar size (Figure 2). One thing that did was their sign, and indeed the phrase – ‘the sign of the …’ – was commonly used to refer to them. Medieval legal requirements for the display of signs would appear to have lapsed by this time, as magistrates were advised that one was ‘not essential to an inn’, but an ‘evidence of it’.33 Naturally though, one was almost universally displayed. They took four basic forms. Most simply, the name of the house was painted on a wooden board fixed to the wall. This might be accompanied, or replaced, by its pictorial representation. Pepys drank at the Mother Redcap in Holloway, whose sign showed ‘a woman with Cakes in one hand and a pot of ale in the other’. These signs might be the work of journeyman painters, like the Mayfield, Sussex schoolmaster Walter Gale, who painted them along with other odd jobs, but artists like John Crome, William Hogarth and George Morland also turned their hands to them. More elaborate were projecting signs, some spectacularly so. The German Carl Moritz, visiting in 1782, was ‘much astonished’ on the Dartford to London road ‘at the great signboards hanging on beams across the street, from one house to another’. Fourth, the name of the house might be given three-dimensional representation, as the carved signs for the Three Kings and the Three Crowns in London’s Lambeth Hill, or most notably the massive sign for the Bull and Mouth.34

Whilst the signs might be reduced to four essential types, the immense variety of public-house names defies easy categorisation, although Larwood and Hotten’s classic nineteenth-century work on the subject came up with fifteen, and the reader is referred to that and other works on the subject.35 Many were in widespread use: the familiar Angels, King’s Heads, Red Lions, Rose and Crowns, Royal Oaks and others. Patriotism was a common inspiration, not only in numerous allusions to royalty, but also in the commemoration of military and naval heroes, from the now less well-known Granby, Wolfe or Rodney to the universal Nelson and Wellington. Those emblems of national pride – horse and cattle flesh – provided a further dimension of patriotism. The celebrated Yorkshire Bay, for example, gave its name to no fewer than seven York public houses by the 1820s, or the Durham Ox, which for six years from 1801 toured England and Scotland in a specially designed carriage drawing crowds of admirers.36 It is those names with local significance which are perhaps the most interesting. In the 1820s Sheffield thus had its Cutler’s Inn and Cutlers’ Arms and the Old Grindstone; Whitby its Fishing Smack and the Greenland Fishery; Hull the Baltic Tavern and the rather charming Jack on a Cruise and Jack’s Return; and on the opposite coast, Liverpool had its New York Tavern, five Livers and no fewer than twenty Ships.37

The interiors of inns and public houses naturally also varied with the scale of the establishment. The grandest had rooms to match their status. The principal house in Exeter, the New Inn, was rebuilt after the Restoration and embellished with its famous Apollo Room. Its elaborate ceiling displayed the royal arms and those of the See of Exeter and important county families. The George at Northampton at this time boasted forty-one rooms. Most of them were distinguished with individual names: the King’s and Queen’s Heads, Globe, Mermaid, Mitre and Rose rooms among them. At Lancaster, the King’s Arms, the most important of the town’s inns, had in the late 1680s fourteen bedrooms plus special rooms for permanent residents. Their names included the Fox, Greyhound, Half Moon, Mermaid, Swan and Sun. Seventeenth-century Hertfordshire inns had for public rooms a hall and/or parlours, plus named bedrooms. As premises became more substantial through the eighteenth century, this practice seems to have become common. In Kendal, the Royal Oak in 1743 had Green and Red rooms, Far, Middle and First parlours, and in addition a ‘Coffy House’ and ‘Billyard Room’.38 Many alehouses, however, remained small, with probably just two drinking rooms in most town houses by the mid-eighteenth century. This is the pattern commonly met with in London when they feature in the Old Bailey proceedings: a parlour/private room and a tap room, or just kitchen and tap room. This was the arrangement, for example, at the Two Brewers in Vine Street on Saffron Hill in 1764, where a woman was served in the kitchen by the fire. The domestic nature of many establishments may also be seen at the Bull and Butcher in Smithfield in 1767, with the landlady on washday hanging wet washing on the horse in the tap room.39 But even the largest houses had their tap room, or tap, which was sometimes run separately from the main establishment, as we find John Clarkson, for example, in 1755 looking after the tap at the Four Swans, a coaching inn in Bishopsgate Street. This arrangement was also referred to as a tap house, as at the Saracen’s Head, an inn in Friday Street, in 1735. And, further, tap house was also used for those premises attached to breweries, like the Angel tap house in Whitechapel, where we find the brewery staff drinking in 1745. This term too seems to have developed a more general application. The working-class radical Samuel Bamford, on his way from Macclesfield to Leek in 1820, had breakfast at a ‘neat little tap-house’. And in a nice example of yet more variety of terms, he also described it as a ‘pleasant little hostel’, evoking a medieval alternative to inn.40

Whatever the scale of the establishment, another common feature was the bar. This had been in use for some time. An inventory of 1627 records one at the King’s Head Tavern in Leadenhall Street, and Pepys noted the ‘barr’ at the Dolphin Tavern in Tower Street in 1660. At this time it was a separate office and store for drinks and valuables, although it is sometimes described as in the tap room. This was the case, for example, at the Rising Sun in Covent Garden in 1765, where a silver cup which was used to mix rum and water was kept in a cupboard in the bar.41 Its modern form, where the customer is served across a counter, developed with the growth of specialist spirit shops from the 1780s, to be examined below. Another feature of the bar, in both its old and new forms, which became common from the turn of the century, was the beer engine. Patented by Joseph Bramah in 1797, its use, though not under his patent, quickly spread. In busy town public houses it was quick and efficient and did away with the need to bring beer up from the cellar. They were advertised in Leeds, for example, by 1801, but within four years we find one installed in a rural Hertfordshire alehouse, the Rose and Crown at Tewin.42 The prominent pump handles of the beer engine were thus quickly established as a characteristic feature of the public-house interior.

Other fixtures and fittings also varied with the establishment. The grandest inns could be luxurious. In the mid-eighteenth century many of the rooms at the Red Lion at Northampton were lined with hangings and pictures and in three of its principal ones there were nearly ninety yards of tapestry. Furniture included Japanese tea tables and Virginia chairs.43 But most public- and alehouses were becoming more or less comfortably furnished. In the tap room were chairs, or benches, and settles and deal tables on a bare, sanded floor. Some rooms had boxes, or booths to sit in, like the original taverns. We find this, for example, in 1752 at a London public house, the Coach and Horses in Swan Alley, Coleman Street, which also had a settle and table before the fire. In parlours there were perhaps carpets and, as in the 1780s at another London house, the King’s Arms in Arundel Street off the Strand, stuffed leather benches fixed to the walls and mahogany tables, in what was described as ‘a very superior public house parlour’. Decorative features like mirrors, pictures, clocks and barometers were increasingly found.44 Nevertheless, there was a huge range of comfort, and there continued to exist fairly basic establishments. Thus, for example, a traveller to the Lake District in 1821 enjoyed the ‘delightfully situated’ Lowwood Hotel overlooking Windermere, with its ‘elegant upper room’ furnished with piano and organ. But he also enjoyed an overnight stay in an inn ‘of the old school’ in the remote Kentmere valley. There, the floor of the main room was ‘bespread with tubs, pans, chairs, tables, piggins, dishes, tins and other equipage of a farmer’s kitchen’, and wash-hand basin or a looking glass ‘seemed luxuries unknown to the unsophisticated natives’. Similarly, in the country near South Cave in the East Riding of Yorkshire, Robert Sharp, a local teacher, called in March 1829 at the Malt Shovel, ‘a real hedge Alehouse’. In its one room the fireplace had no chimney piece, and the fixtures included a tin can ‘used for airing the Ale of such customers who chose that indulgence’ and ‘a collection of old black tobacco pipes’, which the landlady assured him were ‘superior to clean ones’.45

Here, with the hedge alehouse, we reach the base of our hierarchy, where we also find places referred to as pot houses. Although an early reference of 1724 is to a Hermitage pot house in London, described as ‘large and well accustomed’, it clearly was used generally for a small, basic alehouse. In Leeds, in December 1772, the landlord of what the newspaper described as a little pot house fell down the cellar steps going to get a pint of ale. Edward Jackson, the vicar of Colton, north of Ulverston, had to make do with a ‘paltry pot house’ in Langdale in June of 1775. Rather less sniffily, another clergyman, Parson Woodforde, enjoyed porter with his brother and ‘some jolly Tars’ at a ‘Pot-House on the Quay’ at Yarmouth in May 1790. But these too could be comfortable enough. Towards the end of our period here, Samuel Bamford found excellent lodgings ‘at a respectable-looking little pot-house’ in Leicester, and at Redbourn in Bedfordshire, a ‘delicious repast’ at a ‘very humble pot-house’.46 Later usage seems to have become more self-consciously literary and archaic. Both Dickens in Barnaby Rudge and Thomas Hardy in the Mayor of Casterbridge use it in this way, to describe respectively a man ‘reeking of pot-house odours’, and an old woman behaving badly against the church wall, in a constable’s words, ‘as if ’twere no more than a pot-house!’47

The variety of drinking establishments is not yet exhausted, however, and we must return first to the tavern, which we saw Pepys frequenting as a specialised place for the sale of wine and food. As a distinct type they continued to trade well into the eighteenth century. Samuel Johnson and James Boswell used the Mitre Tavern in Fleet Street, which the latter described in 1763 as ‘an orthodox tavern’. Johnson himself, in his famous encomium, confirms that: ‘No, Sir; there is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn.’ At Bath in 1769, the Old Queen’s Head Tavern and Eating House advertised its daily ‘genteel ordinary’ at two o’clock.48 Outside the capital, however, their numbers remained small. At Norwich, for example, a commercial directory of 1783 listed just four taverns separately from the inns, including the Three Cranes, the derivation of whose name we saw earlier.49 It was of course open to the keepers of inns, or indeed alehouses, to take out wine licences, and in this way the distinction might become blurred. Defoe noted the vintner who kept the King’s Arms Inn at Dorking in Surrey, but at Bramber in Sussex, where the chief house was described by him as a tavern, he wrote of the proprietor as ‘the vintner, or ale-house-keeper rather, for he hardly deserv’d the name of vintner’. Similarly, in London in 1740, the Black Boy in Saint Catherine’s was described by its proprietor as ‘both a Tavern and an Alehouse’.50

Thus the tavern began on the one hand to lose its distinctive status, and on the other, the fact that they were not subject to the requirement of a justices’ licence contributed to their association with vice. This was not entirely new. Pepys had used taverns for sexual encounters on several occasions, enjoying, for example, claret and a ‘tumble’ with Doll Lane at the Swan in Westminster in November 1666. Boswell too might relish the intellectual cut and thrust with Johnson and others at the Mitre, but he also tells us of having sex with two women whom he paid with a bottle of sherry in a private room at the Shakespeare’s Head, a tavern in Covent Garden.51 Within a few years of this transaction, magistrate Sir John Fielding was inveighing against the ‘brothels and irregular taverns’, for which Covent Garden was a prime location. Prostitutes, he alleged, appeared ‘at the windows of such taverns in an indecent manner for lewd purposes’. Nor was this confined to the capital: in dockyard towns like Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth the proprietors traded under wine licences. The parliamentary committee to which Fielding gave this evidence resolved that their grant be restrained. This was not effected until 1792, however, when the sale of wine was placed under the jurisdiction of the justices.52 This did not wholly resolve the problem. It was claimed in 1816 by the chief magistrate of Bow Street, Sir Nathaniel Conant, that some old wine licences were still being renewed to houses he described as ‘a higher kind of hotels, kept for the reception of men and women, for purposes which one cannot be blind to’. Furthermore, the rights of the Vintners’ Company had been preserved in 1792 and premises continued to trade under its authority throughout the century.53 Their numbers were, however, insignificant and the word ‘tavern’, rather belying this notoriety, was used generally as another term for, or as part of the name of, an ordinary public house. Commercial directories in their listings distinguished inns from taverns and public houses, but also classified together hotels, inns and taverns, or hotels, inns, taverns and public houses. Within the lists, as at Liverpool in 1824, for example, we find (appropriately) the Irish, New York and North Wales Taverns.54

The coffee house should be noted here, as they occupied a similar social position to that of the tavern in the earlier phase of its existence. They were of course specialist establishments for the sale of coffee, which dated from the middle of the seventeenth century. They were important meeting places for professional, commercial, literary and scientific men. The most famous coffee house is probably that kept by Edward Lloyd, whose City premises, with its booths like those of taverns, was used by marine underwriters and who began to publish his shipping list as early as 1692.55 Maitland’s survey counted 551 coffee houses in London in the 1730s, where their greatest concentration was to be found.56 They adopted names like taverns or inns, above all the Turk’s Head, from the origins of the habit, and they also performed other inn/tavern functions, including the sale of drink. Boswell noted coffee houses selling alcohol, as in April 1763 ‘at the great Piazza Coffee-house, where we had some negus and solaced our existences’. Parson Woodforde, on a visit to the capital in April 1775, ate and slept at the best-known Turk’s Head Coffee House in the Strand.57 By the later eighteenth century the distinctive nature of the coffee house was thus being subsumed into those of the inn or public house. In the Norwich directory of 1783, of three coffee houses listed one was in fact an inn – the Angel in the Market Place. Commercial directories generally listed them with inns and public houses. Those of Baines for Lancashire and Yorkshire did so in the large towns like Hull, York or Liverpool. Inns and public houses also incorporated coffee rooms in their premises, as we saw at the Royal Oak in Kendal by 1743. The coffee house was also fragmenting socially upwards into the private world of the gentlemen’s club, and downwards to a more working-class clientele as coffee became cheaper.58 All-night coffee shops illegally selling spirits and resorted to by people of the ‘worst description of both sexes’ were described to the parliamentary committees looking at the policing of the capital in the mid-1810s. But there were respectable coffee-shop keepers who provided food, particularly breakfast, and also supplied newspapers and magazines. They were as yet few in number, however, and much greater expansion followed further price reduction in the budget of 1825. By 1840 there were nearly 1,800 coffee shops in London.59

The growth in the consumption of spirits caused our final change to the drinking scene. Spirits had been available for public drinking certainly by the mid-seventeenth century. Pepys in March 1660 was taken to an unspecified place in Drury Lane ‘where we drank a great deal of strong water’, and in September 1667 called at the Old Swan ‘for a glass of strong water’.60 The market for spirits remained small, however, until the last quarter of the century, and prior to 1689, when war intervened, consisted mostly of imported French brandy. But from this time onwards British spirits, in effect gin, became: ‘the principal dynamic element in the home market for drink’.61 After 1689 the amount of officially imported spirits (other than smuggled that is) collapsed, and did not exceed the late 1680s figure until the 1760s. In contrast, British spirits excised for sale rose from just over half a million gallons on average per year in 1684–9 to almost three times that by the first decade of the new century, and continued to grow overall to the 1740s, reaching an annual average of over seven million gallons. The estimated share of the drink market taken by spirits rose from 5 per cent in 1700 to over a fifth in 1745.62 For this remarkable growth Parliament was partly responsible by opening up both the distilling trade and the retail sale of spirits. Although sale had in fact at first been limited to those houses licensed by the justices, this had been almost immediately repealed for proving a hindrance to another of Parliament’s aims – the support of agriculture.63

The existing drink establishments naturally took to selling spirits. Surveys of London in 1726 and 1736 showed that about half the spirit retailers were established publicans.64 They were very popular made into punch (mixed with hot water or milk and flavoured with sugar, lemons and spices), and both coffee houses and specialised punch houses sold it from about the turn of the century. Ned Ward, the ‘London Spy’, records the company drinking punch at a coffee house at this time and in 1763 Boswell drank three, three-penny bowls at Ashley’s punch house. The proceedings of the Old Bailey make frequent reference to the drinking of punch.65