Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

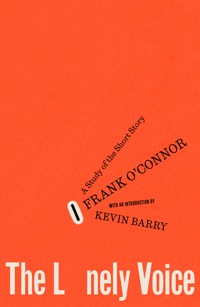

Frank O'Connor was one of the twentieth century's greatest short story writers, and one of Ireland's greatest authors. Lilliput Press are now delighted to continue our publishing of O'Connor's writing by bringing his seminal work on the art of the short story back into print. The Lonely Voice is the definitive work of Irish non-fiction on the art of writing short fiction, and has long been held up as one of the greatest works in global literature on the short form. We are delighted to bring The Lonely Voice back into print with a brand new introduction by Kevin Barry, internationally recognised as one of Ireland's greatests short story writers, whose work - like O'Connor's before him - appears frequently in the New Yorker. Barry engages and parrys with O'Connor's writing, bringing about a meeting of great Irish short story writers from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and bringing this foundational piece of Irish writing to a new generation. The ideal companion to works such as George Saunders A Swim in a Pond in the Rain or John Yorke's Into the Woods: How Stories Work and Why we Tell Them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Frank O’Connor (the pseudonym of Michael O’Donovan) was born in Cork, Ireland, in 1903. He is generally acknowledged as one of the greatest short story writers of the twentieth century, and he was also a novelist and translator of Irish poetry. He wrote his first collection of stories, Guests of the Nation, after being interned during the War of Independence. O’Connor had been an assistant to IRA leader Michael Collins, about whom he later wrote the biography The Big Fellow. He was managing director of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin from 1937–39, before moving to the United States to live off and on from 1952, where he taught at Harvard and Stanford, and wrote stories for The New Yorker magazine among other outlets. He died in Dublin in 1966.

Kevin Barry is the author of four novels and three story collections. His awards include the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, the Goldsmiths Prize, the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award and the Lannan Foundation Literary Award. His stories and essays have appeared in the New Yorker, Granta and elsewhere. His novel, Night Boat to Tangier, was an Irish number one bestseller, was longlisted for the Booker Prize and named one of the Top Ten Books of the Year by the New York Times. He also works as a playwright and screenwriter, and he lives in County Sligo, Ireland.

The Lonely Voice

FRANK O’CONNOR

A Study of the Short Story

Introduction by Kevin Barry

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 1963 by The World Publishing Company

This edition first published 2025 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road,

Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7,

Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © The Estate of Frank O’Connor, 1962

Introduction © Kevin Barry, 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher. Two chapters of this work first appeared in the Kenyon Review before publication.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 84351 924 9

eBook ISBN 978 1 84351 934 8

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro and NY Irvin by Compuscript

Printed and bound in Czechia by Finidr

CONTENTS

Introduction

Author’s Introduction

Hamlet and Quixote

Country Matters

The Slave’s Son

You and Who Else?

Work in Progress

An Author in Search of a Subject

The Writer Who Rode Away

A Clean Well-Lighted Place

The Price of Freedom

The Romanticism of Violence

The Girl at the Gaol Gate

Epilogue

‘The eternal silence of those infinite spaces terrifies me.’

—PASCAL

INTRODUCTION

Kevin Barry

A short story moves like a shadow, a dark presence glimpsed at the corner of the writer’s eye as it passes by, fleetly and silently, but it carries with it a great certainty of feeling – you know at once that it’s a short story. As a writer of stories, you are almost never ready for this lovely and unsettling moment, for the quick passing shade of inspiration, but you know that you must attend to the story at once or it will be gone forever.

Held in the palm of the scholar’s hand for critical inspection, a short story has precisely the weight of a shadow, too – if it works, its success is almost always mysterious, unguessable; if it fails, it can be hard to say exactly where, or why. The book held in your hands will often contradict or act as exception to these rules. In this graceful and unageing study of the form, Frank O’Connor brings into the light all the acumen and attention to nuance gathered in his lifetime’s dedication to the writing and reading of short stories, and in the book’s many insightful moments he helps to illuminate the shadows.

The most persistent of the notions conjured in this book is O’Connor’s famous thesis that a good short story almost always concerns ‘a submerged population group’, a description he himself accepted as ungainly, but any dedicated reader in the form will hear the ring of truth about it. To such groups instanced by O’Connor – Turgenev’s serfs, Sherwood Anderson’s Ohioan provincials, Joyce’s drab Catholic clerks – we can add those who can be identified in the contemporary story, George Saunders’s minimum-wage theme park workers, say, or Jhumpu Lahiri’s expats in Rome. If the novel was to concern itself chiefly with society, the story was to be of the outlaw or the stand-off from society or of those cast aside. The animating spirit that passes through all of these groups is that of our great human loneliness.

O’Connor’s demeanour on these pages in a kind of withering way beguiles us. He has the air of an arch schoolmaster when he skilfully dissects Hemingway, suggesting with a pinched expression that the clean, well-lighted place exposed in Papa’s version of the short story might have represented a triumph of mere technique over any mastery of subject, that Hemingway’s, in fact, was a technique designed to avoid a great subject, that in effect he was all mouth and no trousers. But O’Connor never takes down a story writer of any reputation without first explicating their approach to the art and praising, where found, their innovations.

He is not always a loveable schoolmaster. Often a contrarian note comes across the page seemingly for the sake of it, or maybe to rile an adversary, as when he suggests that in some regards Leskov ‘is the truer artist’ than Chekhov. Of course, who is to say that he is wrong – there are not so many of us reading Leskov on the buses home these days. It is a melancholy aspect of reading this collection, actually, that it transports us to a seemingly more learnéd and clearly a better-read and altogether a more serious-minded era – there is an aura of proper contemplation about this work that gives a calmness and weight to its critical deliberations, no matter that you might disagree with them, and such an aura is unimaginable in our current frazzled and hot-fried state.

The essays in this collection were delivered as a course of lectures at Stanford University in 1961 and there is a palpable sense of O’Connor revelling grandly in the attention and the Californian light. He likes to season his discourse with peppery asides and gossipy extras, and the reader can easily imagine the ghost of a fatal Corkonian smile rising on O’Connor’s features when he airily dismisses the advice offered to him by Liam O’Flaherty, that if he wanted to write short stories, he should really be able to describe a hen crossing the road.

To his credit in this collection, O’Connor seems happiest when he homes in on those short stories that give the sense of inevitability and perfection. One such is Mary Lavin’s ‘Frail Vessel’, which contrasts the fate of two sisters, one who takes a marriage of convenience, the other a love match, and O’Connor delights in the way they measure their subsequent triumphs and failures, the constantly unfolding ironies of the story. Again to his credit, he was among the first to place the work of Lavin at the vanguard of the Irish effort in the short story. He is much less generous when it comes to the stories of the masterful New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, accusing her of all sorts of sentimentality and brassiness and in such a blithe and off-hand way that we suspect a wilful misread.

Even if we don’t always agree with its lofty judgements or sardonic asides, there is the sense in The Lonely Voice of a sparky and pugnacious intelligence. There is a sense, too, of O’Connor lining up the big shots – Joyce, Maupassant, Gogol, Woolf, Babel – and taking them on, one by one, Cork against the world. He was raised on Blarney Street as plain Michael O’Donovan, and the special air that wafts across such streets informs the natives that they are as good as anybody, and that their opinions are worth as much. Corkonians are perhaps the Italians of Ireland, or more precisely the Neapolitans – in the prideful hold of the shoulders and the haughty elevation of snout there is posed always a single question: who’s better than us? O’Connor, his keen mind operating on the engine of this born confidence, couldn’t be more of a Corkonian if he tried.

Of course to even mention Cork brings to mind the way the writer made it carnate in his own memorable short fiction. What gives The Lonely Voice its pitch of authority is our knowledge that O’Connor speaks and writes as a great practitioner of the form. There are very few stories written now that have the intensity and indelible atmosphere of ‘Guests of the Nation’, or the great charge of antic life and energy in a story like ‘The Mad Lomasneys’. He was absolutely a natural in the form, he was designed for it, and he brings that natural feel or nous to bear when he surveys the great names at work in the short story. Witness the way he shows how Turgenev, in a story like ‘Old Portraits’, disguises the deep artfulness of his style with a casual, reminiscent note – it takes a lot of craft and a lot of drafts to make a story read so lightly, so easily, but this sense of lightness and casual intimacy is, in fact, a trap set for the reader, luring her into the unbearable poignancy of the story’s closing stretches.

O’Connor is always adept when it comes to assessing style in the great story writers – he approaches the basic unit of the English language sentence as a kind of writerly DNA, and looks at how it both confines the writer and can set them free. He’s fascinated by James Joyce, a story writer who abandoned the form, and O’Connor recognizes that it’s the ambition in Joyce’s intricate stylistic designs that prompted him to jump ship – of course, there is also the fact that the last story Joyce wrote was ‘The Dead’, and it might have been difficult to see a path forward from there. O’Connor also suspected that Joyce was attempting to run away from the particular ‘submerged population group’ he grew up in – dowdy lower-middle-class Dublin Catholics – and such an escape, as soon as it was made good, would be fatal for the short story writer in him, and so it proved.

The deluded notion that the short story is a kind of apprentice form for the novel is given a shrift as short as it deserves in these eloquent pages. O’Connor rightly points out that the story has much more in common with the play than it does with the novel, with story and play both demanding an immediacy and a sense of direct action, while the novel can waft past like a perfectly pleasant summer breeze. He is perceptive when he points out the attributes that allowed Chekhov to bring both the story and the play into new territory – he recognizes that it was Chekhov’s mastery of the commercial short story, written for penny-ha’penny periodicals and, simultaneously, of the music hall sketch that gave him the necessary technical skills, or the chops in our contemporary idiom, to start playing with the form of both short stories and plays, and actually to break down some of the stale old forms they had settled into and let them breathe again. Such insights are sprinkled with a sense of casual largesse on every page of The Lonely Voice, and what a necessary and welcome resurrection this new edition represents.

AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION

“By the Hokies, there was a man in this place one time by the name of Ned Sullivan, and a queer thing happened him late one night and he coming up the Valley Road from Durlas.”

That is how, even in my own lifetime, stories began. In its earlier phases storytelling, like poetry and drama, was a public art, though unimportant beside them because of its lack of a rigorous technique. But the short story, like the novel, is a modern art form; that is to say, it represents, better than poetry or drama, our own attitude to life.

No more than the novel does it begin with “By the hokies.” The technique which both have acquired was the product of a critical, scientific age, and we recognize the merits of a short story much as we recognize the merits of a novel—in terms of plausibility. By this I do not mean mere verisimilitude—that we can get from a newspaper report—but an ideal action worked out in terms of verisimilitude. As we shall see, there are dozens of ways of expressing verisimilitude—as many perhaps as there are great writers—but no way of explaining its absence, no way of saying, “At this point the character’s behavior becomes completely inexplicable.” Almost from its beginnings the short story, like the novel, abandoned the devices of a public art in which the storyteller assumed the mass assent of an audience to his wildest improvisations—“and a queer thing happened him late one night.” It began, and continues to function, as a private art intended to satisfy the standards of the individual, solitary, critical reader.

Yet, even from its beginnings, the short story has functioned in a quite different way from the novel, and, however difficult it may be to describe the difference, describing it is the critic’s principal business.

“We all came out from under Gogol’s ‘Overcoat’” is a familiar saying of Turgenev, and though it applies to Russian rather than European fiction, it has also a general truth.

Read now, and by itself, “The Overcoat” does not appear so very impressive. All the things Gogol has done in it have been done frequently since his day, and sometimes done better. But if we read it again in its historical context, closing our minds so far as we can to all the short stories it gave rise to, we can see that Turgenev was not exaggerating. We have all come out from under Gogol’s “Overcoat.”

It is the story of a poor copying clerk, a nonentity mocked by his colleagues. His old overcoat has become so threadbare that even his drunken tailor refuses to patch it further since there is no longer any place in it where a patch would hold. Akakey Akakeivitch, the copying clerk, is terrified at the prospect of such unprecedented expenditure. As a result of a few minor fortunate circumstances, he finds himself able to buy a new coat, and for a day or two this makes a new man of him, for after all, in real life he is not much more than an overcoat.

Then he is robbed of it. He goes to the Chief of Police, a bribe-taker who gives him no satisfaction, and to an Important Personage who merely abuses and threatens him. Insult piled on injury is too much for him and he goes home and dies. The story ends with a whimsical description of his ghost’s search for justice, which, once more, to a poor copying clerk has never meant much more than a warm overcoat.

There the story ends, and when one forgets all that came after it, like Chekhov’s “Death of a Civil Servant,” one realizes that it is like nothing in the world of literature before it. It uses the old rhetorical device of the mock-heroic, but uses it to create a new form that is neither satiric nor heroic, but something in between—something that perhaps finally transcends both. So far as I know, it is the first appearance in fiction of the Little Man, which may define what I mean by the short story better than any terms I may later use about it. Everything about Akakey Akakeivitch, from his absurd name to his absurd job, is on the same level of mediocrity, and yet his absurdity is somehow transfigured by Gogol.

Only when the jokes were too unbearable, when they jolted his arm and prevented him from going on with his work, he would bring out: “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?” and there was something strange in the words and in the voice in which they were uttered. There was a note in it of something that roused compassion, so that one young man, new to the office, who, following the example of the rest, had allowed himself to mock at him, suddenly stopped as though cut to the heart, and from that day forth, everything was as it were changed and appeared in a different light to him. Some unnatural force seemed to thrust him away from the companions with whom he had become acquainted, accepting them as well-bred, polished people. And long afterwards, at moments of the greatest gaiety, the figure of the humble little clerk with a bald patch on his head rose before him with his heart-rending words “Leave me alone! Why do you insult me?” and in those heartrending words he heard others: “I am your brother.” And the poor young man hid his face in his hands, and many times afterwards in his life he shuddered, seeing how much inhumanity there is in man, how much savage brutality lies hidden under refined, cultured politeness, and my God! even in a man whom the world accepts as a gentleman and a man of honour.

One has only to read that passage carefully to see that without it scores of stories by Turgenev, by Maupassant, by Chekhov, by Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce could never have been written. If one wanted an alternative description of what the short story means, one could hardly find better than that single half-sentence, “and from that day forth, everything was as it were changed and appeared in a different light to him.” If one wanted an alternative title for this work, one might choose “I Am Your Brother.” What Gogol has done so boldly and brilliantly is to take the mock-heroic character, the absurd little copying clerk, and impose his image over that of the crucified Jesus, so that even while we laugh we are filled with horror at the resemblance.

Now, this is something that the novel cannot do. For some reason that I can only guess at, the novel is bound to be a process of identification between the reader and the character. One could not make a novel out of a copying clerk with a name like Akakey Akakeivitch who merely needed a new overcoat any more than one could make one out of a child called Tommy Tompkins whose penny had gone down a drain. One character at least in any novel must represent the reader in some aspect of his own conception of himself—as the Wild Boy, the Rebel, the Dreamer, the Misunderstood Idealist—and this process of identification invariably leads to some concept of normality and to some relationship—hostile or friendly—with society as a whole. People are abnormal insofar as they frustrate the efforts of such a character to exist in what he regards as a normal universe, normal insofar as they support him. There is not only the Hero, there is also the Semi-Hero and the Demi–Semi-Hero. I should almost go so far as to say that without the concept of a normal society—the novel is impossible. I know there are examples of the novel that seem to contradict this, but in general I should say that it is perfectly true. The President of the Immortals is called in only when society has made a thorough mess of the job.

But in “The Overcoat” this is not true, nor is it true of most of the stories I shall have to consider. There is no character here with whom the reader can identify himself, unless it is that nameless horrified figure who represents the author. There is no form of society to which any character in it could possibly attach himself and regard as normal. In discussions of the modern novel we have come to talk of it as the novel without a hero. In fact, the short story has never had a hero.

What it has instead is a submerged population group—a bad phrase which I have had to use for want of a better. That submerged population changes its character from writer to writer, from generation to generation. It may be Gogol’s officials, Turgenev’s serfs, Maupassant’s prostitutes, Chekhov’s doctors and teachers, Sherwood Anderson’s provincials, always dreaming of escape.

“Even though I die, I will in some way keep defeat from you,” she cried, and so deep was her determination that her whole body shook. Her eyes glowed and she clenched her fists. “If I am dead and see him becoming a meaningless drab figure like myself, I will come back,” she declared. “I ask God now to give me that privilege. I will take any blow that may fall if but this my boy be allowed to express something for us both.” Pausing uncertainly, the woman stared about the boy’s room. “And do not let him become smart and successful either,” she added vaguely.

This is Sherwood Anderson, and Anderson writing badly for him, but it could be almost any short-story writer. What has the heroine tried to escape from? What does she want her son to escape from? “Defeat”—what does that mean? Here it does not mean mere material, squalor, though this is often characteristic of the submerged population groups. Ultimately it seems to mean defeat inflicted by a society that has no sign posts, a society that offers no goals and no answers. The submerged population is not submerged entirely by material considerations; it can also be submerged by the absence of spiritual ones, as in the priests and spoiled priests of J. F. Powers’s American stories.

Always in the short story there is this sense of outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society, superimposed sometimes on symbolic figures whom they caricature and echo—Christ, Socrates, Moses. It is not for nothing that there are famous short stories called “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” and “A Lear of the Steppes” and—in reverse—one called “An Akoulina of the Irish Midlands.” As a result there is in the short story at its most characteristic something we do not often find in the novel—an intense awareness of human loneliness. Indeed, it might be truer to say that while we often read a familiar novel again for companionship, we approach the short story in a very different mood. It is more akin to the mood of Pascal’s saying: Le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis m’effraie.

I have admitted that I do not profess to understand the idea fully: it is too vast for a writer with no critical or historical training to explore by his own inner light, but there are too many indications of its general truth for me to ignore it altogether. When I first dealt with it I had merely noticed the peculiar geographical distribution of the novel and the short story. For some reason Czarist Russia and modern America seemed to be able to produce both great novels and great short stories, while England, which might be called without exaggeration the homeland of the novel, showed up badly when it came to the short story. On the other hand my own country, which had failed to produce a single novelist, had produced four or five storytellers who seemed to me to be first-rate.

I traced these differences very tentatively, but—on the whole, as I now think, correctly—to a difference in the national attitude toward society. In America as in Czarist Russia one might describe the intellectual’s attitude to society as “It may work,” in England as “It must work,” and in Ireland as “It can’t work.” A young American of our own time or a young Russian of Turgenev’s might look forward with a certain amount of cynicism to a measure of success and influence; nothing but bad luck could prevent a young Englishman’s achieving it, even today; while a young Irishman can still expect nothing but incomprehension, ridicule, and injustice. Which is exactly what the author of Dubliners got.

The reader will have noticed that I left out France, of which I know little, and Germany, which does not seem to have distinguished itself in fiction. But since those days I have seen fresh evidence accumulating that there was some truth in the distinctions I made. I have seen the Irish crowded out by Indian storytellers, and there are plenty of indications that they in their turn, having become respectable, are being outwritten by West Indians like Samuel Selvon.

Clearly, the novel and the short story, though they derive from the same sources, derive in a quite different way, and are distinct literary forms; and the difference is not so much formal (though, as we shall see, there are plenty of formal differences) as ideological. I am not, of course, suggesting that for the future the short story can be written only by Eskimos and American Indians: without going so far afield, we have plenty of submerged population groups. I am suggesting strongly that we can see in it an attitude of mind that is attracted by submerged population groups, whatever these may be at any given time—tramps, artists, lonely idealists, dreamers, and spoiled priests. The novel can still adhere to the classical concept of civilized society, of man as an animal who lives in a community, as in Jane Austen and Trollope it obviously does; but the short story remains by its very nature remote from the community—romantic, individualistic, and intransigent.

But formally as well the short story differs from the novel. At its crudest you can express the difference merely by saying that the short story is short. It is not necessarily true, but as a generalization it will do well enough. If the novelist takes a character of any interest and sets him up in opposition to society, and then, as a result of the conflict between them, allows his character either to master society or to be mastered by it, he has done all that can reasonably be expected of him. In this the element of Time is his greatest asset; the chronological development of character or incident is essential form as we see it in life, and the novelist flouts it at his own peril.

For the short-story writer there is no such thing as essential form. Because his frame of reference can never be the totality of a human life, he must be forever selecting the point at which he can approach it, and each selection he makes contains the possibility of a new form as well as the possibility of a complete fiasco. I have illustrated this element of choice by reference to a poem of Browning’s. Almost any one of his great dramatic lyrics is a novel in itself but caught in a single moment of peculiar significance—Lippo Lippi arrested as he slinks back to his monastery in the early morning, Andrea Del Sarto as he resigns himself to the part of a complaisant lover, the Bishop dying in St. Praxed’s. But since a whole lifetime must be crowded into a few minutes, those minutes must be carefully chosen indeed and lit by an unearthly glow, one that enables us to distinguish present, past, and future as though they were all contemporaneous. Instead of a novel of five hundred pages about the Duke of Ferrara, his first and second wives and the peculiar death of the first, we get fifty-odd lines in which the Duke, negotiating a second marriage, describes his first, and the very opening lines make our blood run cold:

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive.

This is not the essential form that life gives us; it is organic form, something that springs from a single detail and embraces past, present, and future. In some book on Parnell there is a horrible story about the death of Parnell’s child by Kitty O’Shea, his mistress, when he wandered frantically about the house like a ghost, while Willie O’Shea, the complaisant husband, gracefully received the condolences of visitors. When you read that, it should be unnecessary to read the whole sordid story of Parnell’s romance and its tragic ending. The tragedy is there, if only one had a Browning or a Turgenev to write it. In the standard composition that the individual life presents, the storyteller must always be looking for new compositions that enable him to suggest the totality of the old one.

Accordingly, the storyteller differs from the novelist in this: he must be much more of a writer, much more of an artist—perhaps I should add, considering the examples I have chosen, more of a dramatist. For that, too, I suspect, has something to do with it. One savage story of J. D. Salinger’s, “Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes,” echoes that scene in Parnell’s life in a startling way. A deceived husband, whose wife is out late, rings up his best friend, without suspecting that the wife is in the best friend’s bed. The best friend consoles him in a rough-and-ready way, and finally the deceived husband, a decent man who is ashamed of his own outburst, rings again to say that the wife has come home, though she is still in bed with her lover.

Now, a man can be a very great novelist as I believe Trollope was, and yet be a very inferior writer. I am not sure but that I prefer the novelist to be an inferior dramatist; I am not sure that a novel could stand the impact of a scene such as that I have quoted from Parnell’s life, or J. D. Salinger’s story. But I cannot think of a great storyteller who was also an inferior writer, unless perhaps Sherwood Anderson, nor of any at all who did not have the sense of theater.

This is anything but the recommendation that it may seem, because it is only too easy for a short-story writer to become a little too much of an artist. Hemingway, for instance, has so studied the artful approach to the significant moment that we sometimes end up with too much significance and too little information. I have tried to illustrate this from “Hills Like White Elephants.” If one thinks of this as a novel one sees it as the love story of a man and a woman which begins to break down when the man, afraid of responsibility, persuades the woman to agree to an abortion which she believes to be wrong. The development is easy enough to work out in terms of the novel. He is an American, she perhaps an Englishwoman. Possibly he has responsibilities already—a wife and children elsewhere, for instance. She may have had some sort of moral upbringing, and perhaps in contemplating the birth of the child she is influenced by the expectation that her family and friends will stand by her in her ordeal.

Hemingway, like Browning in “My Last Duchess,” chooses one brief episode from this long and involved story, and shows us the lovers at a wayside station on the Continent, between one train and the next, as it were, symbolically divorced from their normal surroundings and friends. In this setting they make a decision which has already begun to affect their past life and will certainly affect their future. We know that the man is American, but that is all we are told about him. We can guess the woman is not American, and that is all we are told about her. The light is focused fiercely on that one single decision about the abortion. It is the abortion, the whole abortion, and nothing but the abortion. We, too, are compelled to make ourselves judges of the decision, but on an abstract level. Clearly, if we knew that the man had responsibilities elsewhere, we should be a little more sympathetic to him. If, on the other hand, we knew that he had no other responsibilities, we should be even less sympathetic to him than we are. On the other hand, we should understand the woman better if we knew whether she didn’t want the abortion because she thought it wrong or because she thought it might loosen her control of the man. The light is admirably focused but it is too blinding; we cannot see into the shadows as we do in “My Last Duchess.”

She had

A heart—how shall I say?—too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

And so I should say Hemingway’s story is brilliant but thin. Our moral judgment has been stimulated, but our moral imagination has not been stirred, as it is stirred in “The Lady With the Toy Dog” in which we are given all the information at the disposal of the author which would enable us to make up our minds about the behavior of his pair of lovers. The comparative artlessness of the novel does permit the author to give unrestricted range to his feelings occasionally—to sing; and even minor novelists often sing loud and clear for several chapters at a time, but in the short story, for all its lyrical resources, the singing note is frequently absent.

That is the significance of the difference between the conte and the nouvelle which one sees even in Turgenev, the first of the great storytellers I have studied. Essentially the difference depends upon precisely how much information the writer feels he must give the reader to enable the moral imagination to function. Hemingway does not give the reader enough. When that wise mother Mme. Maupassant complained that her son, Guy, started his stories too soon and without sufficient preparation, she was making the same sort of complaint.

But the conte as Maupassant and even the early Chekhov sometimes wrote it is too rudimentary a form for a writer to go very far wrong in; it is rarely more than an anecdote, a nouvelle stripped of most of its detail. On the other hand the form of the conte illustrated in “My Last Duchess” and “Hills Like White Elephants” is exceedingly complicated, and dozens of storytellers have gone astray in its mazes. There are three necessary elements in a story— exposition, development, and drama. Exposition we may illustrate as “John Fortescue was a solicitor in the little town of X”; development as “One day Mrs. Fortescue told him she was about to leave him for another man”; and drama as “You will do nothing of the kind,” he said.

In the dramatized conte the storyteller has to combine exposition and development, and sometimes the drama shows a pronounced tendency to collapse under the mere weight of the intruded exposition— “As a solicitor I can tell you you will do nothing of the kind,” John Fortescue said. The extraordinary brilliance of “Hills Like White Elephants” comes from the skill with which Hemingway has excluded unnecessary exposition; its weakness, as I have suggested, from the fact that much of the exposition is not unnecessary at all. Turgenev probably invented the dramatized conte, but if he did, he soon realized its dangers because in his later stories, even brief ones like “Old Portraits,” he fell back on the nouvelle.

The ideal, of course, is to give the reader precisely enough information, and in this again the short story differs from the novel, because no convention of length ever seems to affect the novelist’s power to tell us all we need to know. No such convention of length seems to apply to the short story at all. Maupassant often began too soon because he had to finish within two thousand words, and O’Flaherty sometimes leaves us with the impression that his stories have either gone on too long or not long enough. Neither Babel’s stories nor Chekhov’s leave us with that impression. Babel can sometimes finish a story in less than a thousand words, Chekhov can draw one out to eighty times the length.