4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

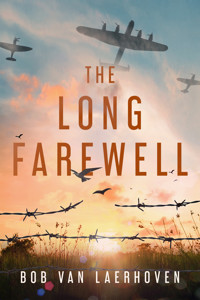

GOLD BOOK LITERARY TITAN AWARD 2025

FINALIST, AMERICAN WRITING AWARDS 2025

A young man with an Oedipus complex in 1930s Dresden, Hermann Becht loses himself in the social and political motives of his time.

His father is in the SS, his mother is Belarusian, and his girlfriend is Jewish. After a brutal clash with his father, Hermann and his mother flee to Paris. Swept along by a maelstrom of events, Hermann ends up as a spy for the British in the Polish extermination camp Treblinka.

The trauma of what he sees in this realm of death intensifies his pessimistic outlook on humanity. In Switzerland, the famous psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung tries to free Hermann of his frightening schizophrenia, but fails to unravel the power of the young man’s emotions, especially his intense hate for his father.

What follows is a tragic chain of events, leading to Hermann’s ultimate revenge on his father: the apocalyptic bombing of Dresden.

THE LONG FAREWELL is an unforgettable exploration of fascism’s lure and the roots of the Holocaust. More than ever, the novel is a mirror for our modern times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

THE LONG FAREWELL

BOB VAN LAERHOVEN

CONTENTS

Note: Military ranks are rendered as below

I. - 1934 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

II. - 1937 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

III. - 1938 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

IV. - 1940 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

V. - 1941 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

VI. - 1943 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

VII. - 1944 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

VIII. - January 1945 -

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

About the Author

Translated from the Dutch by Vernon Pearce

Copyright © 2025 Bob Van Laerhoven

Layout design and Copyright © 2025 by Next Chapter

Published 2025 by Next Chapter

Edited by Carly Rheilan

Cover art by Lordan June Pinote

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

For Carly, her editing powers worked wonders for this hard-to-write novel.

NOTE: MILITARY RANKS ARE RENDERED AS BELOW

Reichsführer – Commander or Himmler

Scharführer – Squad Leader

Obersturmführer – Senior Storm Leader

Obersturmbannführer – Lieutenant Colonel

Sturmbannführer – Second Lieutenant

Hauptsturmführer – Captain

Gruppenführer – Group Leader

ObergruppenFührer – Senior Group Leader

SS – SS

SD – Security Service

- 1934 -

1

“… a genuine peace, founded not on the olive-branch waving of weepy lament, rather on the triumphant sword of a master race that will make the world subservient to the building of a higher culture.”

Marina Nesdrova had an uncomfortable feeling of déjà vu during Hitler’s address. She had heard those self-same arguments fanatically and confidently expressed when she was a young girl in Russia. She knew where such words led.

Hitler’s breaking voice, his tinny Austrian accent, the way he pressed his lips together after the crowd’s hysterical cheering and stroked that ludicrous tear from his eye, arousing her anger and disbelief. She cast an unobtrusive glance sideways. Hans was intently staring at his idol and almost imperceptibly nodding. Her husband’s brown uniform seemed too large for him, though it fitted his slender form like a glove.

Marina was undecided as to which was the worst: the hysterical voice of that little man whose head jerked about like a cockerel and stuck his chest out at every burst of applause or the marching music played in preparation for the Nazi leader’s arrival. She was disgusted at the pompous banners with their ridiculous runic symbols, which hung above the trees of Brühl’s Terrace. And at Hitler executing his St. Vitus’s dance on the platform opposite the breathtakingly beautiful Cathedral.

At that moment, as though he had been reading her thoughts, the statesman shouted, “Mark my words, fellow citizens: you cannot be a good Christian and a good German simultaneously!”

Marina clenched her teeth. This man was influential; his puny exterior was purely deceptive. She closed her eyes, and the white plains of Stanoviche surfaced in her mind like a threatening image of future events.

She quickly glanced to one side and noticed Hans peering at her from the corner of his eye. He blames me for not listening closely; he blames me for being a Catholic, a Belarusian, a melancholy creature, a useless mother; lately, he’s been blaming me for being alive.

Marina Nesdrova had come to Dresden in 1919 as a refugee from the Russian revolution. She had converted to Catholicism then, and now, fourteen years later, she professed its orthodoxy all the more fanatically: after all, Catholicism preached the easy remission of sins. Her husband Hans Becht had once adhered to Protestantism; now it was Hitler. Like that man up there, he is obsessed with ancient, bloodthirsty Teuton gods.

Marina briefly glanced right at her son Hermann. Lately, he had been the only one to come into her bedroom when she was suffering one of her bad days: lying in bed overwhelmed by an icy fear, with a pain inside her that could only be a harbinger of death. Alcohol was the only thing that helped at such times, and with the bottle close at hand, she would lie and wait for it all to pass. She neglected housework and family. Hans no longer even bothered to pretend to be concerned and slept downstairs. Despair and self-reproach chained her to the bed, and no one offered any ounce of solace except her son, who would occasionally come and sit beside her on the bed, silent, but sometimes caressing her hair. She couldn’t respond. She could only stare blankly into the void. Once in a while, he would play a record for her; there were times when Tchaikovsky provided some succor.

But Hermann was fifteen and would soon dismiss his mother as a gloomy old woman. Before long, he would be joining the Hitler Youth and blowing the bugle for that maniac who stood like a tiny doll on his immense podium. And if Hans succeeded in his long-held dream of gaining access into the ranks of the SS, then Hermann, as the son of such a distinguished man, would be sent to an elite camp to be trained as a future member of the black order.

To the right of Hitler rose the silhouette of the Zwinger Palace. This choice of venue probably harked back to the glory bestowed on the palace by Saxon rulers, a glory Hitler wanted to see reflected on the whole of Germany. In Marina’s eyes, however, his brown figure sank into nothingness against the architectural splendor of the backdrop. He’s a pear: his hips are broader than his shoulders, and his jodhpurs make his legs look even shorter than they are.

She sensed the rapture flowing from the crowd towards Hitler and streaming back to them, apparently intensified. This isn’t normal. I’m imagining things. Or else I fail to understand. After all, can I be the only one amongst thousands who doesn’t feel the rapture?

At that moment, Hitler’s voice broke. His body swayed jerkily from left to right as he shouted, “Do you not feel my love for you? Well, now, I feel your love too, and this makes me, and every one of you, stronger than anything on earth!”

The response was a deafening howl. Swastika flags were raised high, drums rolled. Hitler bent his torso backward and went to stand a couple of meters away from the microphone with hands on his waist, lips compressed, wiggling about on his toes, practically dancing round the microphone. The crowd gave the salute. Marina’s arm rose as well – there was no choice, that much she had learned – but she noticed that Hermann’s salute was also apathetically given. He was looking at the band, not at the Führer.

Marina also noticed a furious glance from Hans; his eyes flashed a message she couldn’t decipher. Hans hadn’t lost his good looks. Although he was slowly becoming bald, his remaining hair was curly and blond, and his face escaped the fleshy look typical of Germans. Hans had a full, soft mouth and lovely long eye-lashes. In civilian clothes, he looked smart. His movements were vivacious and elegant yet seemingly deliberate. She stretched her hand out more forcefully, trying to radiate the same sentiment as the rest of the crowd: the kind of pious devotion that belonged at a Christmas dinner.

A waiter, she thought. I, a woman from a worthy old family, have a former waiter for a husband, and now he distrusts me. She suppressed the recollection that in 1919, this maître d’ from the Alte Meister restaurant had proved the sole way out for a Belarusian singer in a mediocre band.

2

I long to forget, but my heart refuses to. How often have I tried to write this down, constantly searching for a fresh way to put into words the thing that poisons my life? Fourteen years ago, before we left Staroviche, Matj told me that politics was our curse. It is a curse that now turns against me almost laughably: Hans is so deeply bewitched by the racist mumbo-jumbo of his idol that he is beginning to suspect me of having Jewish blood in my veins. The Germans don’t realize that if they only go back far enough, they’ll find that the whole of Central Europe has Jewish blood. I have nothing I can say to counter his suspicions; I can’t offer conclusive evidence that I am free of Jewish blood. Such relatives of mine as the Soviets failed to murder live far away. Ironically enough, this has one advantage: at least I cannot be called a communist as well as a Jewess. But I do slow down his career in the SA: he’s been telling me this for years now. My non-Aryan descent is an impediment for him. Whenever he says this, I reply, like a litany, that my father stemmed from old Russian stock and was even Tsar Nicholas II’s court composer for a while. When I said this yesterday, he gave an utterly insane reply, affecting a pensive look and half turning away: “I’m told that Jews make good musicians.”

I was left speechless and could only shake my head. I no longer recognize him. He used to be elegant and well-mannered. I could watch him for hours. Now he fancies he’s the Teutonic wolfman Hitler keeps blabbering about. And I fear the wolfman is smelling blood.

The Germans have found a name for the target of their bloodlust: Jew. True or false doesn’t matter here – that’s what it’s come to. His friends give him the same sideways glances that he gives me: Hans Becht is married to a Belarusian. She can hardly be a Commie – but Jewish… any frightened Belarusian could be a Jew. Hans, my husband, has been sniffing suspiciously all around me and has passed his verdict: I reek of fear.

I cannot even determine whether Hermann is my ally in this domestic conflict. I give him his piano lessons, but he resembles his father in the Hitler Youth uniform that he dons on Sundays. As a maître d’ Hans looked stylish; his livery lent him dignity, but in his SA uniform, he is shapeless. And the same applies to his son, my son.

Hermann is mine; he is Hans’s too, but to what extent is he also himself? He has dark, curly hair from me, hands from my father, and beautiful eyes from Hans. He is an enigma. He gives the impression of listlessness but tries to get out of the house as often as possible. In that respect, he also resembles Hans. At least I know that Hans is fully occupied and preparing for his transfer to the SS, but I know nothing about what Hermann is up to. Which of the two is the worst?

When my husband does spend a little time at home, all I hear about is his latest hobbyhorse, the SS, the elite. He says the SA’s time has passed; the future belongs to the SS. Some people love it in a uniform; the more overblown the get-up, the better they feel. Perhaps Hans is like this, and the black tunics make him yearn to join the SS. He’s so tenacious and crafty that he’ll somehow manage to get into that uniform and those thin black leather gloves, but in the meantime, his son is wandering through the streets of Dresden and staying away from home after school. When I ask where he hangs out he replies: with friends. He practices Hitler Youth activities with them: field games and war games. Or so he says. I have never set eyes on those friends of his. But Hermann is fifteen and a child no longer. The men of this house grind me to pulp, crush me flat as a pancake.

What goes on in their head is a mystery to me.

It’s Saturday afternoon. When Hermann was a toddler, we often went to Dresden Heath. I can still hear his peals of laughter. On all fours, Hans would let him ride piggyback or climb a tree to impress him. Hans was an agile, self-assured climber who reveled in his son’s admiring glances. I jokingly suggested he remove his shirt and trousers one summer day to look like Tarzan. When he did so, he looked all pale and skinny, but to me, he was handsome.

Nowadays, Saturday afternoons mean an empty home and memories. Maybe Hermann and Hans don’t have those anymore; they have not been on good terms lately. Hermann is short, and his hair is dark – not what his father expected. And I think that Hermann sees his father differently, too. They communicate formally, distantly, without bothering to hide their mutual indifference.

There is enmity in this house. Shapeless and festering so far, not entirely surfacing, but undoubtedly present. It is poisoning us all, with Nazism at its source. At times, I catch a glimpse of my husband as I once thought I knew him – for example, in the evenings or when he is tired. But that uniform is like a magician’s cloak, turning him into a wolfman.

3

The water splashed upwards as the pebble skimmed over its surface, then sank. Carla Kienholz picked up another. “I can do better than that,” she said, stroking curls from her face. Carla wore a dark frock with a white collar and was perspiring, though it was somewhat cooler by the pond of the Grosser Garten. She glanced at Hermann, and he nodded. She threw the pebble. The sun joined the game as if a glittering water snake were drawing a trail through the water.

“Good at it, aren’t you!” said Hermann. He had met Carla less than two months ago as she sat in the park with a sketchbook, drawing the swans on the stream. She didn’t use the precise, detailed style Hermann had learned; instead, she sketched in vague stripes and shadings, graceful, smooth, yet lifelike. He had asked if she might be willing to teach him; at school, he was particularly good at drawing the valiant figures of Germanic heroes.

Carla was animated when she talked about her father, who was an artist. “My father is a friend of Hitler’s,” she had said when they parted after their first encounter. “They were at art school together.” She was less forthcoming about her mother, a scion of a wealthy family. “Mother says she’s a clairvoyant, but I have doubts.”

Hermann had not replied.

After glancing critically at where the pebble had finally sunk, Carla turned round. “Weren’t you supposed to go to the Hitler Youth meeting?”

“I had no mind to.”

“Sooner or later, someone will tell your father.” Hermann shrugged his shoulders. “My dad is painting Hitler’s portrait,” she pursued. “It’s going to be four meters high and three meters wide.”

“My dad wants to join the SS. He’s some bigwig even now. I hardly ever get to see him these days.” It was the first time Hermann had spoken to her about his father.

Carla turned round and grabbed yet another pebble. From her movements, he could see that she was cross. Carla Kienholz had a broad face, with long curly hair and dark eyebrows that lent her a domineering look. She was far removed from that blond, pigtailed girl in the Nazi League of German Girls, who smiled self-confidently with a swastika-adorned collection box in the poster at school, with its caption, Help build Youth Hostels and Homes. It struck him that she somewhat resembled the Jewess in Streicher’s The Poisonous Mushroom, a children’s book that he had been given at school; its message was a warning that Jews can be hard to tell from Gentiles, just as it is challenging to tell poisonous toadstools from edible mushrooms. But at least Carla’s nose wasn’t fat and ugly like the Jewess, but snub and tip-tilted.

Hermann hadn’t so far been to Carla’s home. Neither had she asked for his address. It wasn’t fitting for a girl with such prominent parents.

“Father says that I, too, will have to join the SS later on,” Hermann continued,” so that I can all the better serve our Führer who is making Germany great again. Did your father come and listen to the Führer’s speech last week? Did he talk to him, perhaps?”

“My dad even travels to Berlin to see him.”

“My mother hates Hitler,” said Hermann tonelessly, sitting down. “But she isn’t German. Want to hear a secret?”

She sat down beside him and pouted her lips. She nodded. “I peep into her diary. She writes in it almost daily.”

“Is she Jewish?” Carla Kienholz asked gravely.

“Well, well,” came Stefan Reisner’s voice behind them. “Hermann Becht promises to attend the meeting but prefers to waste his time with filthy Jewish pigs.”

Hermann glanced round. Stefan Reisner, as usual, looked self-assured in his Hitler-Youth uniform. Shirt, tie, belted shorts, socks, shoes – everything about him was tidy. His cap tilted at the prescribed 45-degree angle, and the runic symbol on his left sleeve radiated force. A few boys in the same uniform stood next to him, sneering. Hermann didn’t know them all, but Stefan he knew all too well: he was his form’s loud-mouth, full of his father being a member of the SS. The year before, his class tutor, a woman in her forties with a flat hairdo and an amiable attitude towards her pupils, had told them breathtaking stories about Greek gods. Stefan Reisner had stood up and, in a well-rehearsed tone, said: “We no longer wish to listen to those stories of yours about non-German gods.” And he had stiffly sat down again. A strained silence followed. Frau Bargeld looked long at Stefan Reisner, grabbed her grammar, and began her regular lesson. At the rear of the class, someone had started laughing, and everyone burst out in hysterical guffaws while Frau Bargeld, with her back towards them, wrote words on the blackboard without turning round. Hermann, too, had laughed.

“She’s no Jewess,” said Hermann. “Her mother descends from a rich German family.”

“She’s as Jewish as your mother,” said Stefan in the same stiff tone he had adopted towards Frau Bargeld. “But you, at least, are in the Hitler Youth, although you neglect your duties. As for her, she’s nothing whatsoever.”

Carla jumped up; unnoticed, she had picked up a branch and now, with all her might, hit Stefan on the head with it. Stefan flung his arms up and toppled backward to the ground. It was all over before anyone had realized it. Carla faced the three other boys, holding the stick in front of her. Tears were running down her cheeks. Hermann scrambled to his feet. Two of the boys pulled Stefan upright. He showed an ugly cut above the left eye, and his face cramped with pain.

“Get out of here, you bastards!” screamed Carla, her voice cracking. She brandished her stick like the lion tamer Hermann had once seen swinging a chair during a circus performance in the Old Town. The boys turned tail, dragging Stefan Reisner along with them. Carla threw the branch down and covered her eyes with her hands. Hermann watched the boys trot off.

“I must go home,” he said, wanting to run after Stefan to demonstrate his allegiance to them.

“I wish I had never been born,” Carla said, sitting down and enfolding her knees with her arms.

“Is it true that you are Jewish?” Hermann ventured. For a while, there was silence.

“There’s a land somewhere, I’m certain there is,” Carla replied, “where people don’t laugh at each other. Where one can jump into a pond without any clothes on, just like that, and keep floating along.”

Hermann Becht saw that the boys had vanished and wondered what she might look like without clothes. He stood still; his hands reached down to cover his abdomen.

4

“And mind, you look shocked and distinctly show your disapproval,” said Hans Becht. He had difficulty knotting his SA-tie. “The Führer is bound to be favorably impressed.”

Marina nervously tucked the tie into place herself. “Will he say a few words to you?”

“I’ll take care of that. Just see to it that you keep in the background.”

“And I’m not allowed to speak to him?”

Again, that look out of the corner of his eye. “It’s better not to.”

Hermann listlessly gnawed at his pencil; instead of concentrating on his sums, he eavesdropped on the conversation. He’d realized long ago that he became invisible to his parents by sitting immobile and bending over a textbook. He considered it essential to monitor such conversational fragments: his mother’s diary, which he didn’t entirely understand, and his father's talk about nothing except Germany’s glorious future. Often, both parents would behave unpredictably, which had its dangerous side. Listening in could thus help him adapt.

“But look, don’t you think I might be able to tell Hitler something of interest? After all, the art of painting does attract him. The expressionists are…”

“That’s enough,” Hans sharply interrupted her. “I don’t want to hear no more about it.”

Listening to these kinds of private exchanges often also spelled frustration; it made him feel even more endangered.

“We ought to have left Hermann with the neighbors,” said Marina, putting her coat on. “If anything should happen…”

“Rubbish! He’s nearly fifteen and old enough to look after himself. Shouldering a bit of responsibility is the shortest road to steadfastness. Don’t forget, Hermann, bed at nine.”

Hermann looked up from his arithmetic and nodded. Father seldom raised his voice when speaking to him, but the end of each sentence seemed to hold a veiled threat. At times, just before bed, he would think for a moment of the past, but it was becoming increasingly difficult to recall the man his father used to be. Hans joined the SA when Hermann was eight years old, and since that day, all he had ever talked about was virility, bravery, heroics, duty, and work.

That is why Hermann still donned his Hitler Youth uniform on Saturday mornings, though lately, he had spent most mornings taking Carla to the Grosse Garten, only attending the field games and indoctrination sessions just often enough to avoid suspicion.

He smelled his mother’s eau de Cologne as she kissed him. “Stefan Reisner hit me on the playground today,” he said when his parents were standing by the door. “His father is in the SS, and now he fancies he can do whatever he likes.”

“You must hit him right back, young fellow,” said Hans. “Don’t they teach you that in the Hitler-Youth?” Hermann looked at his father’s shoulders. With his uniform on, they seemed quite a bit wider. “What’s more,” Hans Becht said, “that boy’s dad isn’t one jot better than me.” He swiveled round and vanished through the doorway.

His mother threw him a comforting glance before following. Hermann was irritated. After all, he was no longer a child. He listened to the departing car and closed his arithmetic book.

On the sideboard lay a brochure. On the cover, a black triangle is topped by a white apex and surrounded by a red circle: DEGENERATE ART: Exhibition of Bolshevik ‘Cultural Documents’ and Jewish subversive activities. 28 June 1934, Dresden.

Hermann opened the brochure: paintings of persons with deformed limbs, of a head distorted out of all proportion, of a World War veteran from 1918, of a negro’s head with swollen lips. There were also prints of physically and mentally abnormal people: a baby with water on the brain and a deformed right eye, a practically bald woman wearing a feral smile, another woman with insane-looking eyes, enormous pendulous breasts, and a tiny flat-topped cranium.

Hermann slammed the brochure shut. He glanced at the mirror next to the sideboard, grabbed his jacket, and left the house. He carefully slipped the back door key into his pocket.

5

Hermann Becht gazed upwards as he arrived at Carla’s house in M. D. Poppelmans Street. In a city famous for its buildings, this one stood out. All the houses of the Wilsdruffer quarter were old and stately – after all, it was part of the Old Town – but the one Carla inhabited had something more to offer: the elegance of incipient decay. It had a poorly maintained magnificence, like a gentleman in a ceremonial dress with wine stains on his collar. Hermann rang. He could smell freshly baked bread through the open lattice window in the door. A man opened the door. He was short, and his shoulders glimmered; under a leather apron, his torso was bare. His abundant light-grey hair was clipped at the temples, and his face was still youngish.

He looks slightly scared, thought Hermann.

“Yes?”

“I am Hermann Becht,” said Hermann softly. “Is Carla in, Sir?”

“She is.” The man retreated a step. Hermann entered the hall. A door opened at the back, revealing Carla. “Hermann!” she said, “have you come to help with my homework? Let’s go up to my room.” She beckoned to him and went up the staircase. Hermann hesitated, glanced at Carla’s father, saw no sign of disapproval, and followed Carla upstairs. “Are you allowed to do this?” he asked in a low voice. He felt he was expected to speak in a whisper, just like in church, where he had to accompany his mother every Sunday.

6

Hitler’s mouth hung half open. Dressed in the lackluster uniform with its riding-breeches and knee-high boots, he was absent-mindedly sticking his stomach out. He stood there like an embarrassed schoolboy, left arm dangling and holding his cap, right hand clenched into an impotent fist. Goebbels, a rat sporting a broad smile, his glistening, black-haired head never still for a second, was wearing a light overcoat with twin rows of buttons. He stood a few paces in front of the Führer and glanced backward, smiling. His smug face showed the adoration of a form’s top pupil eyeing his beloved teacher.

Marina looked across Hans’s shoulder. He was attempting to edge closer to the Führer.

She noticed how Hitler’s eyes were blinking nervously. This event is something he cannot control by uniforms and steel.

SA-chief Röhm was the first to leave the group standing behind Hitler. Oozing boredom, he approached one of Erich Heckel’s paintings and stopped in front of it, hands clasped behind his back. Marina saw the massive neck beneath the military cap.

Fat neck and boots, I see too many of them. I live amongst uniforms.

Marina tried to concentrate on the paintings. She liked expressionists; their vision was gloomy and threatening but, at the same time, contained a sensitivity that attracted her. The Aryan artistic ideal so dear to Hitler: she had it seen in “Art in the Third Reich.” She found its ostentatiousness static and ludicrous.

At long last, Hans managed to get into conversation with the Führer. She saw him point out specific details on the canvasses. Hitler was nodding, glancing almost timidly at him. A waiter was carrying drinks around. Hitler took nothing, and neither did Hans, but Röhm helped himself with an authoritative gesture. Goebbels lifted his glass from the tray while bent forward as if intending to sniff the drinks.

Marina thought of Hermann. She felt he was the only person who amounted to any refuge in her life: his introspective silence was a sign of steadfastness and common sense to her. It was a pity that there have been too few opportunities to talk with him for the past year. There had been so many obstacles; her doubts and the momentum of Hans’s career had made strangers of them. She suddenly felt a violent longing to get away from this mockery of an exhibition, to go home and discuss all these matters with her son. She would explain why his father had changed so much, why she was suffering so intensely. If she told him what had happened in her life when she was scarcely older than he was now, he might perhaps come to understand her.

7

“That’s right,” said Carla. She stood by the window of her room, averting her face but with her head proudly held high. “I lied. My dad is a Jew. He has relatives in Palestine. But my mother is wealthy.”

Hermann certainly wouldn’t have minded owning a handsome room like this one. Its high stuccoed ceiling and the elegant furniture caught his fancy. “So your father doesn’t paint Hitler?”

“No, he doesn’t, Hitler Youth boy.”

“That’s fine with me. Their entire setup is ridiculous. The strongest lead the show there, not the cleverest.”

“I don’t believe you. Your father is in the SA.”

Hermann started. “You haven’t told your dad about that, have you?”

Carla shook her head, denying her hold over him, and threw him a brief, almost mocking glance.

“I hope you didn’t tell him my dad wants to join the SS?”

“Oh no, that I didn’t do either.”

“You must never tell him. Promise?”

“And why not?” She had a cunning look on her face – she knew all too well why not.

He looked around the room; already, he felt at home there. “I mightn’t be allowed back if you did.”

“I’m reading a book,” she said as if she had been considering something. “About a Jew who hates Society, possibly also himself. I’m confused; it’s not an easy read, but I’m trying.”

“Couldn’t we read it together?”

She smiled. “It’s called ‘Prairie Wolf.’If only that were my name.”

8

Röhm and Hitler stood beside each other: the boar and the fox. Marina could think of no better comparison. Röhm squared up before the Führer, almost touching him, his entire demeanor exuding swagger and conviction. Marina discreetly edged a bit closer, pretending to examine the paintings. She listened with eyes averted, just as her son often did.

“It’s only normal, Adolf!” said Röhm, one of the few to address Hitler so familiarly. “Germany will not be saved by those damned aristocrats, a bunch of reactionaries, the blessed Reichswehr. What Germany needs is the men of the SA, the front-line troops! With the SA under my command, you can prove to the armed forces that you are far from powerless. But in that case, the SA can no longer be treated like dirt. The Army must recognize us!”

“I have spoken to Major-General von Blomberg,” Hitler replied softly. “My dear Ernst, what you ask is impossible. I can nominate you Minister without portfolio, but the Reichswehr will never stand for being outstripped by the SA.”

“There are two million of us!” said Röhm. He bent even closer to Hitler and placed both hands on his hips. “And only one hundred thousand in the Reichswehr.”

“You will have to be patient, my dear Ernst.” Hitler’s voice was as amiable as before. “You know what those Prussian generals are like. They would have difficulty accepting an outsider like you as their leader.” His tone became as sweet as honey. “In any case, we have come here to experience first hand, with our senses, the true extent of Bolshevik and Jewish aberrations. And these, my dear Chief of Staff, go further than your own if the reports I have lately been getting about you are anything to go by.”

Hitler turned on his heel and left these words hanging in the air. Marina took a couple of steps sideways. Hans had told her that Röhm was a homosexual, a disgrace for the entire SA. Marina walked towards the next painting and saw Hans conversing with a group of SA-officers, his eyes directed at Röhm.

Soon afterward, Hitler departed. The waiters making the rounds with beer and wine were kept busy. Röhm joined the little group. His complexion was scarlet; the scar above his nose and right cheek shone wanly. Hans was standing next to him. Marina tried to gather the gist of the conversation by watching Hans’ face, but her husband had put his SA cap on, so she could barely distinguish his features. A few drinks later, Röhm noisily took his leave, slightly unstable and accompanied by his closest adjutants.

Immediately, Hans came towards her. His face looked taut and vacant; she knew he wouldn’t let anything slip.

But as they drove homewards, he remarked, grimly clasping the steering-wheel: “D’you know what he said, what the fellow had the nerve to say? Here are his very words; I shall never forget them: ‘that ridiculous corporal can drop dead for all I care, him with his stupid babbling. Hitler is a traitor; the SA has made an important man of him, and now he wants to liquidate us. But I will not be squeezed into a corner just like that; he’ll soon know how much power I have!’ This is literally what he said.”

She hadn’t seen him that excited for ages. “ls that so?” she replied.

“Don’t you understand?” he snapped with a violent jerk of his head. “If Hitler knew about this, it would spell the immediate end of Röhm, even of the entire SA, I’d bet on it. I was right. The Führer has great plans for the SS, and the SA stands in their way. He’s ever such a clever statesman, Marina!”

Hans stopped the car when they arrived home but left the engine running. “No need for you to stay up – it’s likely to get late,” he said.

Nodding, she descended. Hans was so impatient to drive off that he shifted into first gear without decluttering properly. The gearbox screeched; the car joltingly moved off.

I know where he’s going. I married a traitor. He’s off to denounce his chief, a man given to foolish pronouncements when drunk. What does someone like that do with a wife he has no further use for?

She looked toward the river Elbe’s right-hand bank. Hitler was staying at the resort hotel “Der Weisse Hirsch,” less than ten minutes away from their home.

9

Hermann ran through the Old Town’s dark streets, his heart leaping in his chest. She had kissed him. It hadn’t been as wonderful as boys were whispering at school: she had breathed a mouthful of warm air into him, and her tongue had been dry.

A little later, he grew breathless but kept on running. In Ahenberger Street, two SA-men, by the light of a lantern, were pasting placards all over the windows of three Jewish shops: GERMANS! DEFEND YOURSELVES! DON’T BUY FROM JEWS!

Hermann slowed his pace as he approached them. The two SA-men, one with a cap on and the other wearing a swastika-armband, fixed him. The one with the cap was a bull-necked fellow with a square chin. “Lookee here,” he said, “a Jewboy. Going inside, by any chance, lad? To notify your father, perhaps, and ask him to step outside? Well, I’ll tell you something. He won’t be coming outside, that funk, ‘cos we’d beat the living daylights out of him!”

He had gradually raised his voice, ending up shouting, and came ever closer. Hermann turned away and ran off. Behind him, he heard the men laugh. Hermann bolted through a few streets at random, still looking over his shoulder. When the pain in his chest became too intense, he stood still, finding himself in Bremer Street. “My dad’s in the SA, you stupid bastards,” he murmured to himself, panting. “And before long, when he’s in the SS, he’ll have you hanged.”

He took a deep breath; another ten minutes of running lay ahead. If his parents happened to be back, there would be hell to pay. He concluded that the quickest way home was along Magdeburger Street and flitted on. The street was brightly lit by a huge bonfire burning before the public library. People were standing around it in a circle, and sheets of paper floated above the flames like fairytale bats. Hermann had no intention of withdrawing; the fire attracted him. He saw how SA-men and students tore books apart, laughing as they did so.

“Hey, youngster,” called one of the students. His eyes flashed with an unholy gleam in the firelight; he was short of a front tooth, which lent a sinister aspect to his face. “Shouldn’t you be in bed? Or have you come to help us burn all these books propagating un-German ideas?”

“My father’s in the SA,” stammered Hermann.

“That’s the style, young fellow,” said one of the SA members, a jovial-looking fatty carrying an armful of paper. “Come here; our youth must assist in cleaning up Germany!” He thrust a few books into Hermann’s hands. “Come on, lad, throw them into the fire!”

Hermann glanced at the volumes in his hands. Thomas Mann, he noticed, and also ‘Prairie Wolf’ by Hermann Hesse. “This one too?” he asked.

“Oh, my boy,” said the SA-man, “all books are worthless except the one the Führer wrote, aren’t they? We live in Germany, which is dedicated to action!” He pushed Hermann in the back; the boy ran towards the fire and dumped the load in. Cheers rose. People leaped forward, throwing sheets of paper into the air, slowly descending onto the flames. High-spirited shouts drowned the crackling of the fire. Hermann stayed where he was, staring into the blaze until pushed aside by a bespectacled student who was scarcely able to lug his pile of paper about.

Quickly, he ran off, looking round from time to time. “Prairie Wolf,” he muttered to himself. “Now, who would want a name like that? And it was boring, anyway. She’s probably just as crazy as her mother. I’ll have to watch out for myself.”

Carla, a grave look in her eyes, had told him earlier that evening to behave quite normally towards her mother, even if she acted strangely.