Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

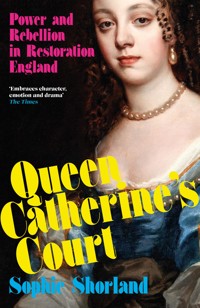

'A good story, embracing character, emotion and drama... refreshing.' THE TIMES 'A splendidly sympathetic and sparky portrait... Wittily written and rich in detail' Miranda Seymour Catherine of Braganza - Boring? Plain? Ineffectual? Think again. Charles II's wife was a trouser-wearing tastemaker who introduced tea drinking, popularised card games and championed baroque fashion and art. Her salon culture was infamous for its parties, theatricals and frequent trips to the pub. A Catholic queen in a strictly Anglican country, she was the diplomatic bridge between an unstable Britain and the European mainland, and carefully navigated the treacherous political landscape of Restoration England. In this illuminating portrait historian Sophie Shorland brings Catherine vividly to life for the first time, revealing a woman who defied the limitations imposed upon her to have a profound impact on the world around her. Previously published as The Lost Queen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 466

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘[An] often delightful biography . . . [Shorland] writes with the confidence of a much more experienced author. She has thankfully discarded the rigid conventions of academia in favour of telling a good story, embracing character, emotion and drama. Her often lighthearted manner is for the most part refreshing, especially given a story so bleak.’ The Times

‘Sophie Shorland’s Queen Catherine’s Court is wonderfully rich in the 17th century details of lives, loves, politics and power, in England and in Europe. The book rightly challenges ideas about the wife of Charles II and his treatment of her. We’ve too easily preferred the gossip of the merry monarch’s mistresses over this remarkable woman showing dignified courage and tenacity in the face of constant threats to her position.’ Suzie Edge, author of Mortal Monarchs

‘What a wonderful subject Sophie Shorland has picked. It’s for far too long that Charles II’s Portuguese queen has been neglected or misrepresented. Shorland connects her to our own times in a splendidly sympathetic and sparky portrait, filled with unexpected images of a courageous woman who wasn’t afraid to create her own circle and defend her beliefs at an English court dominated by her husband’s mistresses. Wittily written and rich in detail.’ Miranda Seymour, author of I Used to Live Here Once

‘Another neglected Early Modern woman finally gets the biography she deserves! Shorland’s is a confident, cosmopolitan and always accessible life of the queen consort who brought England nothing less than the first toeholds of a truly global empire, and the habit of tea-drinking.’ Ophelia Field, author of The Favourite

‘Between these covers we rediscover a lost queen, having now emerged from the shadow of her husband, Charles II. She stands before us as never before, complex, astute and fully realised, all thanks to Shorland’s sensitive and robust retelling of her life. “Let Bonfires blaze” indeed, for here, finally, is the long-awaited history of Catherine of Braganza.’ Anthony Delaney, HistoryHit presenter and author of Queer Georgians

‘A lively and long-awaited biography of one of Britain’s most underrated queens.’ Linda Porter, author of Mistresses

‘This lively, fascinating book retrieves an overlooked queen from a historical siding and restores her to the centre of European politics and Charles II’s London.’ Suzannah Lipscomb, award-winning historian and broadcaster, and author of What is History, Now?

‘What we get is a vivid picture of how, as queen consort, Catherine bore the rebuffs she received politically and socially among certain factions of the court, and how she ultimately rose to become a prominent figure in her own right . . . It succeeds in its aim of restoring Catherine to her rightful place at the centre of Restoration history.’ History Today

‘Gorgeously written with visual descriptions that are so clear that they can be painted on canvas. The level of engagement that the writing provides would make this book a blockbuster movie, filled with sparkling characters fighting for the top spot in the Royal Court.’ World History Encyclopedia

‘An enthralling and vivid portrait of Queen Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II, that reveals her forgotten place in history.’ Smithsonian, ‘The Ten Best History Books of 2024’

First published in Great Britain in 2024 as The Lost Queen by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Sophie Shorland, 2024

The moral right of Sophie Shorland to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, storedin a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

The picture acknowledgements on pp.317-19 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-640-0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland.

www.arccompliance.com

For everyone living forgotten lives

Contents

Key Characters

Prologue

1 Assassination, Education and an Accidental War

2 A Play for the Throne

3 The Bridegroom Hunt

4 Marriage and the Mistress

5 Fashion and Frivolity

6 Plague, Fire and New York City

7 Divorce

8 Plots True and False

9 The Queen Dowager

10 Return and Regency

Epilogue

Endnotes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Index

Key Characters

Afonso VI – King of Portugal, Catherine’s brother

Anne Stuart, Duchess of York – Catherine’s sister-in-law, daughter of Edward Hyde

Anne Stuart – James II and Anne’s daughter; later Queen Anne

Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury – politician, prominent antagonist of Catherine and James II

Barbara Palmer, Countess of Castlemaine – Charles II’s principal mistress in the first half of his reign

Charles II – King of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1660 to 1685

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon – Lord Chancellor, Charles II’s chief adviser

Frances Stuart, Duchess of Richmond – Catherine’s close friend, distant connection of the royal family

Francisco de Melo e Torres, Marquês de Sande – Portuguese ambassador to England, Catherine’s godfather

Henriette-Anne, Duchess of Orléans – Charles II’s youngest sister; later sister-in-law to Louis XIV

Henry Hyde – politician, involved in a legal wrangle with Catherine; later 2nd Earl of Clarendon

James Crofts, Duke of Monmouth – Charles II’s eldest illegitimate child

James Stuart, Duke of York – Charles II’s brother and heir to the throne; later James II

João IV – King of Portugal, Catherine’s father

Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth – Charles II’s principal mistress in the second half of his reign

Luisa de Guzmán – Queen of Portugal, Catherine’s mother

Maria Sophia of Neuburg – Queen of Portugal, wife of Pedro II

Marie Françoise of Savoy – Queen of Portugal, wife of both Afonso VI and then Pedro II

Mary Beatrice of Modena – James Duke of York’s second wife

Mary Stuart – James II and Anne’s daughter; later Mary II, Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland

Pedro II – King of Portugal, Catherine’s youngest brother

William of Orange – Mary Stuart’s husband and cousin; later William III of England and William II of Scotland

Prologue

WHEN QUEEN CATHERINE of Braganza entered London for the first time in May 1662, knots of people formed in the city’s twisting medieval streets, jostling to catch sight of their new queen. It was overwhelming and hot, and she stood stiffly, looking a little like a doll. She didn’t speak a word of English, but nobody minded that. An effusion of terrible but joyous poetry followed in her wake, celebrating her recent marriage to Charles II, himself newly restored as king after the tumult of the Civil War and then Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate.

Catherine would be England’s Restoration queen. Although the Restoration is frequently ignored in favour of its more famous relative, the Tudors, the period is generally associated with hedonism, flirtation, silks, heavy drinking and finally the human embodiment of all these things: the Merry Monarch Charles II himself. It has given us the poetry of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, whose favourite rhyming couplet involved ‘arse’ and ‘tarse’ (penis). It was a time of great scientific discovery, of invention and the relatively early days of colonialism. Following the killjoy Parliamentarian era and the Protectorate, Charles’s reign has usually been associated with fun, at least onstage and screen. The return of the Royalists unleashed female actors onstage for the first time, wearing scandalously tight breeches or hiking their skirts up to reveal a shocking amount of leg. Dancing and Christmas were allowed again. Of course, history is always more complicated than that. Opera actually flourished in Cromwell’s reign. But we will leave the nuances of this debate for another book.

What concerns us is a shadowy figure at the edge of this hedonistic tale of the Restoration. She was present at a meeting with famous architect Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London had destroyed the city. She was observing the sky just as Isaac Newton was trying to work out Earth’s place in the solar system and how exactly meteors worked. In one way or another she was present for every great event of Charles’s reign. But in history she has remained a spectre in the background. Her story has effectively been lost.

For the last 350 years or so, the very few mentions of Catherine have placed her reputation at rock bottom. She has been characterised as an unintelligent, cheated-on wife who had very little impact on the world. As her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography casually states: ‘Catherine had not been unwilling to fulfil her role as the British queen consort but circumstances conspired to make her success unlikely. Her “ordinary mind” and lack of beauty and sophistication disappointed her court, and while she came to love her husband, who for his part welcomed her non-interference in politics and praised her goodness, his mistresses were the bane of her life, and her childlessness the cause of great misery.’1 Other accounts have gone further, branding her reign a failure thanks to her childlessness.

The definitive biography of her life, while much more sympathetic, has not helped matters. Written by Lillias Campbell Davidson and published in 1928, it has a distinctive early-twentieth-century feel in enumerating Catherine’s virtues: ‘Catherine lived in her husband’s court as Lot lived in Sodom. She did justly, and loved mercy, and walked humbly with her God in the midst of a seething corruption and iniquity only equalled, perhaps, in the history of Imperial Rome. She loved righteousness and her fellows, and, above all, the one man who won her heart on the day of her marriage, and kept it till the grave shut over her. She was one of the purest women who ever shared the throne of England.’2

How boring! A hundred years later, purity and humility are not very fashionable virtues for a woman, and this version of Catherine seems like a rather embarrassing chapter in our current telling of history, one that is being rewritten to include strong women who forged their own paths. Campbell Davidson’s description skates over Catherine’s love of parties, fun and gambling. She smiled far too much. She dressed all her ladies in matching costumes, played with cross-dressing and scandalised the prudish by displaying her slim ankles.

I first became interested in Catherine of Braganza as a historical woman when visiting the National Portrait Gallery, its rows of kings and queens predictably grave and unsmiling. That is, until I reached the portraits of Charles II and Catherine. Not only is Charles half smirking back at the viewer, he is surrounded by portraits of women – his mistresses – shining in satin and gazing seductively out from their frames. I knew enough of history to know that other kings had had mistresses who had been powerful and influential, so why were they not pictured? Why was Charles singled out and Catherine – by extension – obscured?

It is often forgotten that, while her husband had plenty of lovers, Catherine was still the queen. Throughout history, she has been compared unfavourably with her husband’s mistresses, the real women who ran the show. In the last century, there have been at least four books written about the mistresses, with two in the last decade.3 Catherine has also been blamed for Charles’s sexual licentiousness, as though a man having an affair is somehow his wife’s fault. Her Wikipedia entry tells us that ‘Catherine’s personal charms were not potent enough to wean Charles away from the society of his mistresses.’4 If only she had been more beautiful, more charming, more clever and more worldly, perhaps he would not have strayed.

Compared with any constitutional monarch in the UK today, Catherine had unfathomable levels of power. She had immense spending capacity, alongside influence as a diplomat and patron of the arts. She was a taste-maker, popularising tea, for example, which was to become a feature of life that is still closely associated with English national identity. She commissioned art and music, turning English tastes towards the baroque, then a highly avant-garde new style yet to be fully adopted in England. Many an eighteenth-century church would probably be missing its curlicues or golden cherubs without her. If we think of the fun and the hedonism of the Restoration, it is impossible to remove Catherine’s presence. The organiser of countless parties, theatricals and trips to one watering hole or another, she developed her own distinctive salon culture.

Catherine took her role as a diplomat very seriously, regularly corresponding with other heads of state, the King of France, Louis XIV, responding to her missives in a sprawling, extravagant hand that reflects the man himself. Indeed, throughout Europe at the time, the art of diplomacy was often seen as a queen’s primary function. Many of the diplomatic visits that took place during Charles’s reign were conducted in Catherine’s rooms, and it was a sign of favour if Charles asked a visitor to kiss the queen’s hands. She was an active participant in these important diplomatic exchanges. In fact, her very arrival in England was a diplomatic act, hurling England into war with Spain.

Throughout her childhood and the first eight years of her reign in Britain, Portugal was fighting a fierce war with Spain for independence. Rather than – as historians tell us – Catherine and Charles II’s marriage being immediately disliked by the English because of her Catholicism,5 her arrival in England was heralded as a union of two oppressed powers. In the vein of ‘the enemy of our enemy is our friend’, Catherine’s anti-Spanish associations vastly outweighed her Catholicism, one poet crying, ‘Let Bonfires blaze, and Bels out loud Ring’ at the coming of Queen Catherine.6

Furthermore, her dowry brought the first Indian possession into British hands, as well as the important port of Tangier. She is the woman after whom Queens in New York is named, and there remain several streets in London named after her. She found positions for her friends and supporters in both the English and Portuguese courts, and would later become regent of Portugal, ushering in a new era of Anglo-Lusitanian alliance that still exists today.

It is convenient – and suits our modern version of monogamy – to see the relationship between Catherine and her husband’s mistresses as one based on rivalry. But the reality is far more complicated. Charles’s mistresses were often friends of the queen, and they spent a great deal of time together. Barbara Palmer, Countess of Castlemaine, perhaps the most influential of the mistresses, copied Catherine in having her portrait painted as Catherine of Alexandria, the queen’s namesake. It has been assumed that this was a deliberate insult to Catherine, showing off Barbara’s superior charms in the same posture, but if we look more closely at the historical record, we see a whole spate of such pictures, mostly from Catherine’s supporters and as a compliment to her. Could their relationship in fact have been one of both collaboration and competition, containing a range of complex human emotions?

Rather than portraying her as either pitiable or pure, a new and more complex picture of the real woman emerges. Catherine was plagued by fits of depression throughout her life. As a dedicated hypochondriac, she loved to self-medicate, but she was also great fun, laughing and talking too much and too enthusiastically. Visitors to court were shocked by this informal woman who showed too many teeth. She was mostly uninterested in English politics, but cared passionately about Portugal, doing everything she could to preserve its independence. She was not a great social reformer, but she advocated for more liberties for women, and left money in her will to free slaves.

This biography attempts to show Catherine neither as a saint nor a sinner, but rather as a woman of her time, living in an era of immense scientific, global and social change, who had a profound impact on the world around her. All the reasons why she has so far been largely forgotten by history – her wonky teeth, her fits of depression and the odd bout of social awkwardness – in fact make her a hugely relatable figure to us today, when we accept the imperfect and the difficult life.

1

Assassination, Education and an Accidental War

THE SIGNAL WAS a pistol shot. As the sound rang out, a group of conspirators stormed Lisbon’s Ribeira Palace, the seat of power and the home of the viceroy. It was an incredibly risky enterprise; the few conspirators were pitted against the might of the Hapsburgs, the most powerful dynasty Europe had ever seen. They demanded both an end to Spanish rule and a new king. The new king they called for was a shy man who had spent most of his life buried in the countryside and had no experience of politics. His name was João, Duke of Braganza.

João’s daughter Catherine was two years old when the revolution began. She was not born Infanta (Princess) of Portugal, but into the risky business of would-be royalty and imminent civil war. Her childhood was one of plots, assassins and the whispered legend of a hidden king who would come forth to solve the nation’s ills. While she may not have been born an infanta, however, she was a daughter of Portugal’s wealthiest and most powerful aristocratic house. The Braganzas were responsible for around 80,000 vassals and owned over a third of Portugal’s land.1 They were also royalty, with a significant claim to the throne.

To understand the Braganza claim, we need to travel a little in time and space. A visitor to northern Morocco in 1578 would have observed two armies camped on either side of the Loukkos River, at Alcácer Quibir: King Sebastian of Portugal with his ally the deposed Sultan Abu Abdallah Mohammed II on one side, facing the current Sultan of Morocco, Abd Al-Malik I, on the other. They were lining up to fight a battle that was only ever going to end one way. Sebastian had ignored warnings about taking an army to the heart of Morocco, and the Portuguese were doomed: his force of 24,000 troops faced Al-Malik’s army of 50,000.2 It was a slaughter. All three kings would die in the ensuing battle, known in memoriam as the Battle of the Three Kings.

Since no one had seen the young, impetuous King Sebastian die at Alcácer Quibir, and no clearly identifiable body was found, four fake Sebastians emerged in the years following the battle, all claiming to be the lost king and capitalising on the popular belief that he could not really be dead. In Portugal today, ‘Sebastianism’ still has mythological power: one of his titles is ‘Sebastian the Asleep’, and it is believed that, at a time of great national need, he will emerge from wherever he is sleeping to fight for his country once more.3 At birth, his astrologer had predicted that Sebastian would have dark hair and would enjoy the company of women, concluding that the presence of Venus in the Eleventh House signified multiple sons.4 The astrologer was wrong on all counts. Sebastian had light hair, no wife and no issue. After his death, only his cantankerous elderly uncle, the Cardinal Henrique, remained as the clear heir to the ruling Portuguese House of Aviz.

As a servant of the Church, Henrique could have no legitimate children, and the Pope refused to release him from his vows of celibacy. The cardinal’s death in 1580 inevitably led to a succession crisis for the Portuguese crown, for which Sebastian unfortunately stayed asleep. There were three contenders for the throne, all grandchildren of Manuel I, Sebastian’s great-grandfather: the illegitimate António, Prior of Crato; King Philip II of Spain; and finally Catarina, Duchess of Braganza. With the resources of the world’s greatest empire behind him, Philip II emerged the winner and Portugal became part of the Hapsburg Empire.

King Philip was descended from Manuel’s daughter, while the Duchess of Braganza was descended from his son, Duarte. As Portuguese succession prioritised the male line, it was technically Catarina who had the greater claim to the throne. She had an international reputation as ‘a Couragious and very Witty Princess, well skill’d in the Greek and Latin tongues, as also in the Mathematicks and other curious Sciences, which she carefully instructed her Children in’.5 They were an educated, cosmopolitan family, and as the wife of the wealthiest nobleman in Portugal, Catarina would have been able to afford the very best tutors for her children, including Catherine’s grandfather, Teodósio.

Teodósio was a page and favourite of the much-mythologised King Sebastian, who took the ten-year-old with him on campaign to Morocco. When the fighting at Alcácer Quibir began to get dangerous, he sent the boy behind the lines. This was not acceptable to Teodósio, who stole a horse and charged recklessly into the heart of the ill-fated battle. He was taken prisoner, but on hearing of his valour, the new Sultan of Morocco, Ahmad al-Mansur, released him without ransom, a high compliment for the boy’s incautious bravery.6 Luckily for Philip II, Teodósio was uninterested in the throne of Portugal, and faithfully served the new king as he had Sebastian. He was rewarded with even more lands to add to the vast Braganza patrimony.

It was on these huge estates that Catherine was born, between eight and nine in the evening on 25 November 1638, St Catherine’s Day. It was a fortuitous date in the Catholic calendar. St Catherine had been a princess and scholar, one of the three ‘holy maids’ who provided protection against sudden death, and whose voice was heard by Joan of Arc. Catherine would identify with her namesake throughout her life.

The third child of João and Luisa, she was baptised just over a fortnight after her birth in the opulent chapel of her family home, the Vila Viçosa. Its monolithic foundations had been laid by her ancestor Duke Jaim I, who wanted to live in something a little more modern than the draughty fourteenth-century castle that still stands today. Everything about the Vila Viçosa celebrated the wealth and power of the Braganza dynasty, from the huge square outside, designed to gather crowds and make the palace look even grander, to its tapestries, its lacquered cabinets imported from Asia, and its hundreds of intricately painted azulejos (tiles). For the first few years of her life, Catherine grew up in this vast structure, looking out over silver-green olive groves and the reddish bark of cork oak.

The family remained in countryside retirement rather than enjoying the bustle of Lisbon for two reasons. The first was that their claim to the throne of Portugal meant that they were a constant threat to Spanish rule merely by existing. The second was a character trait that helped João and his family survive many tumultuous years of politics and intrigue: the Duke of Braganza was a naturally cautious, retiring man. He was not particularly flamboyant and did not have a taste for power.7 His greatest pleasures were music, reading and the life of the mind.

Music was a family tradition that Catherine too would inherit, along with the Braganzas’ intense spiritual life. In his will, João’s father, Teodósio, had written, ‘I remind my son, the Duke, that the best thing I leave him in this house is my Chapel,’ and instructed him to maintain the chaplains and musicians within as one of the chief cares of his life.8 In a move relatable to teenagers and their frustrated parents everywhere, he forced João to continue with his music when as a boy he rebelled against lessons and wanted to give it up. Despite this flicker of early reluctance, music was to become one of the chief passions of João’s life.9 Some of his compositions are still played today; we may owe the tune of ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful’ to him. He was a virtuoso of polyphony, experimenting with six voices, and also wrote technically on the subject. Catherine’s childhood was filled with excellent and experimental music, something that continued to fascinate her later in life. Like her father, she was interested in anyone, regardless of rank, who could create beautiful sounds, and never tired of her musicians.

When the English poet and musician Richard Flecknoe visited Lisbon in 1648, João ‘no sooner understood of my arrival, but he sent for me to Court’. They had two or three hours ‘tryal of my skill’, and João apparently greatly exceeded Flecknoe, especially when it came to composing music. However, he was well pleased, and gave Flecknoe permission to see him as often as he liked. Returning the flattery, Flecknoe wrote some very bad poetry about Lisbon and its environs, stressing the marvellous surroundings and – to him – exotic fruits such as ‘Silk animating Mulberies’ and ‘Pomegranads’.10 The rhymes get considerably worse towards the end of the poem, finishing with the dubious combination ‘Hesperides ’ and ‘Alcinous’es ’. This inspired forcing of language led to considerable fame for Flecknoe, though not of the type he dreamed of, with the better-known and better-respected poet John Dryden calling him ‘Through all the realms of Non-sense, absolute’.11

Besides music, João’s other great love was hunting, and a French visitor attributed his unassailable good health to this form of physical exercise, riding out for long days on the trail of spotted fallow deer or long-toothed wild boar. João was of average height and slightly stocky, with brown hair neither light nor dark, and pale eyes.12 Perhaps his most distinguishing feature was his dramatically curling brown moustache. He liked to dress all in black with gold buttons and braid; in the seventeenth century, wearing black was a sign of wealth as well as sobriety, since the garments had to be dyed multiple times for the colour to look anything other than a nondescript grey, and washing quickly faded the garment.13

Catherine’s mother, Luisa de Guzmán, was artistic like her husband, but enjoyed painting over music, using a trowel to apply thick oil paints to canvas.14 She was a gifted linguist, picking up languages easily, including Portuguese (she was Spanish), and her education was humanist, although highly focused on religion.15 Her youthful 1632 portrait (when she was 20) shows an oval face with rosy cheeks, dramatic black eyebrows and an intense gaze. Like João, she seems to have favoured expensive and fashionable black, enlivened with delicate white lace and deep pink ribbons. Together they were a power couple. It had made sense for one of the richest families of Spain to marry the richest of Portugal. And the Guzmán fortunes were vast: when Luisa’s grandfather inherited his lands, over 400 folio pages (the biggest size of paper then available) were needed to record all his properties.16

However, their marriage was by no means a foregone conclusion. João’s father, Teodósio, was looking further afield for a bride, and had fixed on Maria Catarina Farnese, the daughter of the Duke of Parma.17 Ambitious for his son and his dynasty, Teodósio required a lady with both dowry and international connections. He may also have been seeking to bolster the Braganza claim to the throne, since Maria Catarina was a cousin of sorts, descended from João’s grandmother’s elder sister. However, João was rejected by Maria Catarina and her family, and when his father died in 1630, he was still unmarried. He was now the grand old age of twenty-six, and the question of an heir to carry on the dynasty was becoming urgent.18 Unsure of where to look, and aware of the importance of marriage, he wrote to close family friend Francisco de Melo, then resident at the Spanish court, asking him for advice.*

De Melo was loyal to his Spanish master, the Count-Duke Olivares. Effectively the prime minister for the entire Hapsburg Empire, Olivares was almost as large in stature as he was in personality. Ruthless, dynamic and willing to work himself to exhaustion, he was unafraid of unpleasant tasks. And he needed to be – the empire spanned continents, from New Spain in the Americas to the Philippines in Asia, and much of Europe. All papers requiring King Philip IV’s signature went through Olivares first.19 Spain’s policy in Portugal was geared towards greater Iberian union, attempting to neutralise any threat of Portuguese independence. And thanks to his claim to the throne, João was one of the greatest symbols of that independence. His marriage was a delicate matter for Olivares. How could he turn this problem into an advantage for Spain? To promote unity, Olivares had long been trying to arrange Spanish–Portuguese matches. What better than for João to be similarly tied to Spain? He instructed de Melo to recommend one of Spain’s wealthiest and best-connected maidens as a bride, Olivares’ own relative Luisa de Guzmán, of the House of Medina Sidonia.

De Melo duly wrote to João that ‘The Count-Duke informed me he would be pleased if Your Excellency would make this marriage to reunite the two largest houses in Spain’ (referring to Portugal and Spain as one, and to a past match between the houses of Medina Sidonia and Braganza). United, de Melo argued, they could carry out the ‘service and maintenance of Spain’.20 Ironically for the future leader of an independence movement, these arguments found favour with João, and he agreed to the match. Luisa, it was assumed, would do what was good for Spain, and for the Guzmáns as a family. She would act as a diplomat and mediator, as countless other barely remembered women in history had done. Little did anyone know that she had been brought up to think of ambition as the greatest aristocratic virtue. She would prove to be the dynamic force behind her husband’s political career, propelling the Braganza dynasty from dukes to kings.

For now, João had ticked off that most important of tasks for a feudal lord: securing the future of the dynasty. To celebrate his betrothal, he ordered two hundred torches to be lit, an extraordinary extravagance of fuel, while the whole village of Vila Viçosa was filled with shouts of approval and festivities.21

In the cool of the autumn of 1633, when Luisa had just turned twenty and João was twenty-nine, the couple were married by proxy on the Spanish side of the border, in the ancient city of Badajoz, its encircling walls and labyrinthine fortress seeming to rise from the rock. Luisa travelled to Portugal as a married woman, despite not yet having met her husband. It must have been an anxious time for her, but she was made of stern stuff. Apparently her ambitious father’s parting words were: ‘Go, daughter, very happy, for you are not going to be a duchess, but a queen.’22 There were many such legends surrounding her. Another was that on the day of her baptism, a Moorish guest announced that the little girl would live one day to be a queen.23 Although both prophecies are almost certainly later imaginings, they speak to the legend that Luisa was to become for Portugal. It was a symbolic moment for the whole Iberian peninsula as the dark-eyed young woman crossed the waters of the Río Caya into her new home and her new country.

João and Luisa finally met at a second marriage ceremony on 13 January 1632, at the fortress-like Our Lady of the Assumption Cathedral in the town of Elvas – this time on the Portuguese side of the border. Dusk was just beginning to fall, tinting the butter-yellow stones of the cathedral a deeper orange. Both bride and groom were determined to make a good first impression. João was dressed in an almond-coloured velvet overdress ornamented with gold braid, a gold choker, and a hat glittering with diamonds. Not to be outdone, Luisa wore an enormous diamond necklace and a green dress showcasing her family’s wealth, partly through the great quantity of unnecessary material employed in the dress’s sleeves; there were four of them, cut open to reveal a taffeta lining, embroidered with flowers of silver thread and decorated with yet more diamonds.24

The marriage seems to have been a happy one. Luisa adapted to her new life as though she had been born in Lisbon, and quickly learned Portuguese, as well as the customs of the country.25 She had a persuasive tongue and ‘an insinuating way’ that ‘drew all mens hearts . . . and had by her extraordinary Application and Carriage gained an absolute Ascendant over her Husband, who never undertook anything of moment without her Advice’.26 Their peace was only disturbed when João’s brother Duarte had an affair with one of Luisa’s ladies-of-honour, shocking the religious and deeply conservative duchess. The irresponsible Duarte was sent away from the palace, only for João himself to embark on an affair with a travelling actress.27 However, this was short-lived and more socially acceptable by the standards of the time, since it did not involve any of Luisa’s ladies. Women were expected to accept their husband’s dalliances, as long as it did not interfere in their domestic sphere. Essentially, it was more acceptable for an aristocratic man to have a discreet affair with a lower-status woman.

While overseeing the vast ducal interests and pursuing their artistic pleasures in the countryside – João at his music and Luisa at her easel – the young couple were firmly on track to secure the dynasty. This was not without its heartbreak, however. Like her mother before her, Luisa was plagued by miscarriages. But in 1634, she carried a baby to term. They called him Teodósio, after his grandfather, and in the spirit of goodwill invited the wayward Duarte back to the fold, making him Teodósio’s godfather.28 A girl they named Joana came close on her brother’s heels in 1635, followed by Catherine in 1638. Two further children, Manuel and Ana, tragically died when they were hours old.

The main differences between João and Luisa seem to have been in ambition and decision-making. While Luisa knew what she wanted and was quick to side with one cause or another, João was more careful. This often served him well, as many problems find their own inevitable solution if left to time. Luisa was intelligent and decisive, well aware of the risks of the political game that the family would soon be playing, and the undercurrents of dissent circulating through Portugal. As Duchess of Braganza and claimant to the throne of Portugal, she famously announced, ‘Better queen for one day, than duchess all my life.’29

__________________

* De Melo was a trustworthy pair of hands. The whole family would prove invaluable to the Braganza dynasty, and Francisco, Catherine’s godfather, would be particularly important in her life and reign.

2

A Play for the Throne

POPULAR DISSENT IN Portugal had been brewing against Spain for longer than João had been alive. Besides questions of national identity, much of the dispute revolved around money. During the early honeymoon days of Iberian union, a new river route to Spain had been proposed. Greater wealth and trade opportunities seemed to be on their way. The Portuguese also gained access to New Spain, a vast territory spanning from California and Florida to southern Mexico and the Philippines, and to the Spanish silver there, mostly mined in terrible conditions using coerced labour. However, as the Spanish economy stuttered, so too did Portugal’s. The Hapsburgs were constantly fighting wars of one kind or another on multiple fronts. As fast as the silver was mined, it was spent again – on luxuries, foreign mercenaries and arms. No industry was fostered within Spain or Portugal. A vast influx of Central American silver led to an inflation crisis across Europe, since more money was being put into circulation without more goods being produced, leading to a price spiral.

The latest conflict was the bitterly destructive Thirty Years War, which raged through Europe from 1618 to 1648, decimating its population and resources. Spain was seriously in need of money, and Olivares looked to Portugal to raise it.

Used to relatively light taxation, the Portuguese protested at tax rises, coming as they did on top of a run of bad harvests. Farmers resented the Spanish for taking food from their mouths, and the provincial gentry resented them for taking their power. Traders were dissatisfied too: thanks to Spain’s long-running conflict with the Netherlands, they could not bargain freely with the Dutch, a huge, very wealthy market and one of their most important trading partners. Portugal’s position as an effectively Spanish nation made them fair game for Dutch and British incursions into their ships and territories in Brazil and Asia.1 The country simmered with resentment.

In 1637, large-scale disturbances broke out in Évora, southern Portugal, and like a spark to tinder, riots ignited throughout the south. Increasingly, the protests were not just about money, but about the very idea of being ruled from Spain. Popular dissent swirled, with a sepia-tinted version of Portugal’s glorious past revivified. People fantasised about how much better, how much richer Portugal would be if only they weren’t under the Spanish yoke.2 Influential was a semi-messianic text written by a lowly cobbler from Beira Alta, in the south. His mystical writings foresaw a new age for Portugal, after an encoberto, or hidden king, came forth to liberate his people. It was stirring stuff, imagining through metaphors like the pruning of vines how the country would be cleansed and remade. Other prophecies circulated seductively, telling of old hermits seeing a line of kings, or threescore years of chastisement for the Portuguese, followed by God’s mercy. Spain had been ruling them for close to sixty years.3

And who was the encoberto likely to be? There were few claimants to the throne, other than our very own João. However, at this point, he was not very interested in claiming it. He was offered the crown by the rebels but turned it down. Did he not want it, or did he feel that it wasn’t the right time?4 French power-broker Cardinal Richelieu, forever wishing to get one over on Spain, even contemplated supporting illegitimate heirs to the throne, since João seemed so uninterested. Inside Portugal, other noblemen or even a republic were discussed.5 But it was difficult to ignore João – the Braganzas were the biggest landowning family in the country, and roughly a third of the vassals, or peasantry, owed allegiance to him as their feudal lord. He was needed if any rebellion was to be successful.6

Although the riots were eventually suppressed by Castilian troops, they were an important turning point, proving to any would-be revolutionary that Portuguese independence had almost universal popular support.

In an attempt to secure João’s loyalty to Spain and prevent any attempt at independence, Olivares made him commander of Portugal’s royal forces. João accepted in 1638, albeit with every appearance of reluctance, and began touring the country, looking suitably kingly and doing exactly the opposite of what Olivares intended. He was finally out of his countryside obscurity, wielding power and beginning to look like a viable king. The Portuguese leapt on the idea, believing that this man might be ‘the incarnation of Hope’.7 Rumours began to circulate that João was indeed the encoberto, as had been foretold.8 It seems rather a stretch, since he was always quite plainly in sight as the likeliest heir to the throne, but it made an excellent piece of propaganda, and of such tales kings are made. A contemporary account records that he had become such a threat that Olivares attempted to kidnap him and smuggle him safely to Spain, first on a ship that was to pretend to need succour from a storm, and then by Spaniards stationed at various coastal forts. However, luck and João’s large entourage foiled every attempt. The duke continued to gain in popularity as he made his tour of Portugal’s defences.9

As tensions simmered in Portugal, long-held dissent in Catalonia finally boiled over. In the first week of May 1640, the ringing of church bells summoned armed, well-organised revolt against Castilian overlordship. The French, sensing blood in a financially weakened Spain, supported Catalonia. When the call went out for the Portuguese to join the Spanish army being gathered to put down the revolt, and also support beleaguered Spanish forces in Italy, word spread that this was a clever trap to crush Catalonian and Portuguese dissent simultaneously. It was feared that, while the Portuguese nobility were out of the country fighting, Spain would enact its ‘cruel design’, crushing Portugal without the organised resistance the nobles might have offered.10 Something must be done to counteract any such dastardly scheme. But what?

Again the answer was independence, and again came the question: who would be the next ruler of Portugal? Still the obvious answer was João, but, despite his newly regal status, in June 1640 he again refused to accept the crown from a small group of conspirators.11 He knew that he only had one chance: if he allowed himself to be crowned king of Portugal, or even publicly supported rebellion of any kind, it could mean death for himself, his family and the whole Braganza line. The Spanish could not allow them to live if they showed any sign of mutiny.

When asked by conspirators whether, if push came to shove and they founded a republic, he would support the republic or Spain, João replied that he had ‘decided to never go against the common sentiment of the kingdom’.12 This was promising.

The story goes that Luisa provided the final impetus. She told her prevaricating husband, ‘if thou goest to Madrid thou runnest the hazard of losing thy head. If thou acceptest the throne thou runnest the same hazard. If thou must perish, better die nobly at home than basely abroad.’13 However, even this was not enough to convince him. So she brought the family into it, saying to him on Catherine’s second birthday, ‘This day our friends are assembled to celebrate the anniversary of the birth of our little Catherine, and who knows but this new guest may have been sent to certify you that it is the will of Heaven to invest you with that crown of which you have long been unjustly deprived by Spain. For my part, I regard it as a happy presage that he comes on such a day.’14

As the final nail in the coffin of persuasion, she brought in their daughter for some emotional blackmail. Getting Catherine to kiss her father, she asked, ‘How can you find it in your heart to refuse to confer on this child the rank of a king’s daughter?’15

In October 1640, João told the rebel faction that he would accept the kingdom of Portugal. It might have been Luisa’s reasoning that persuaded him: Portugal was boiling over, and, as the best candidate to be king, he must either go with the times or be executed by one great power or another.

The conspirators acted, converging on the Ribeira Palace separately, some by horse and some concealing their arms in litters normally used to carry nobles between merriments.16 There was remarkably little bloodshed, the Castilian troops stationed in the capital surrendering when they saw the way the wind was blowing. The viceroy, Philip IV’s cousin Margaret of Savoy, was left unharmed, fleeing to a convent, although her deeply unpopular secretary, Miguel de Vasconcelos, was hunted down.

Described as ‘a man Composed of Pride, Cruelty and Covetousness, knowing no moderation but in excess’, who ‘gave birth to hatreds & enmities among the Great ones of the Realm’, Vasconcelos had unfortunately become a scapegoat for all of Spain’s crimes.17 There are different versions of his death, but the most popular tells how the rebels found him cowering in a cupboard, trying to cover himself with a stack of papers.18 His bloodied body was defenestrated, thrown to the crowd below, a visible sign that the regime had changed.19 The mob ‘ran like Madmen to express Living Sentiments of Revenge upon his dead and senseless Corps, vaunting who could invent the newest wayes of disgrace and scorn, till at length almost wearied with their inhumane sport, they left it in the Street so mangled, that it did not seem to have the least resemblance of a Man’.20

Bonfires were lit throughout Lisbon, the citizens cheering their new monarch and crying for joy as horsemen rode around the city calling out proclamations in the name of King John IV. As one disconsolate Spaniard put it, ‘John IV was very happy, since his kingdom cost him no more than a bonfire, and Philip IV much otherwise, who had been stripped of so sure a crown only by acclamations and illuminations.’21 It was seen as quite remarkable how fast, how comprehensive and how bloodless the revolution had been. But would it hold?

Spain categorically did not accept this handover of power. The two nations were now at war. Should the full weight of the Spanish juggernaut turn on Portugal, they were likely to be crushed. Luckily for them, Spain was tied up with rebellion in Catalonia, war with France and the Thirty Years War, which would rage across the continent for another eight years.

João was now King of Portugal. Luisa had reached the height of her ambition: she was finally queen. And Catherine had the new title – and the new status – of infanta.

The Braganza family quickly decamped to Lisbon, two-year-old Catherine in tow, alongside her elder siblings Teodósio, five, and Joana, six. She would have been too young to remember the move, although her brother and sister may have recounted it to her. Couriers were dispatched by sea to the far corners of the Portuguese Empire, from Brazil to Tangier to China, with news of the coup. It was widely accepted and even acclaimed throughout the territories, except where Hapsburg control and military might were at their strongest. Accordingly, Ceuta remained with Spain, but Tangier and all the other territories went with Portugal.

The Portuguese parliament, the Cortes, had the power to decide on the succession, and were called in 1641 to approve the choice of João as ruler. They did so with gusto.

His rule was helped hugely by the popular backing for the Braganza coup. State bureaucracy, magistrates and minor clergy were all strongly in favour, and during the long war for Portuguese independence, the povo, or people, continued to support João, whose piety appealed to their traditional attitudes. Without the povo, independence would most likely have failed, since they provided the foot soldiers, the food and the taxes with which war was waged. They also suffered as their fields and houses were burned, their cattle stolen and many of their number killed.22

The monarchs of Portugal had no crowning ceremony. Instead, they held a stately exchange of promises: the monarch swore to serve God and Portugal, while the people, through their representatives, swore loyalty to the monarch. Six years into his reign, in 1646, João introduced his own twist on the classic ceremony of acclamation, dedicating his kingdom to Mary, Our Lady of the Conception, and having her crowned as queen. This pious and humble relationship became an important feature of the Braganza monarchy: no monarch again wore a crown, and in images the crown sat on a nearby table.23

Luisa acted as the power behind the throne, having ‘a goodly presence’ and ‘more of the Majestick in her’ than her husband.24 However, João did enjoy sitting in Portugal’s high court, and gained a reputation as a just king. His title – handed down to history – is ‘the Restorer’, for his role in Portuguese independence.

Now that Catherine was an infanta, her life inevitably changed. Court life in Lisbon was old-fashioned and rather stuffy by contemporary European standards. In a portrait painted when she was around five years old, she stands stiffly, fan in one hand, grasping the back of a chair with the other. Dark-eyed, with delicately arched brows, she looks directly at the viewer, her stance that of a little adult. Her body is swathed in black velvet, sleeves cut open to show the fine linen beneath, and her shoulders are covered in a lace wrap. Her chubby cheeks are the only feature that mark her as a young child rather than a court lady. Portraits of her elder siblings are equally stiff, projecting an iconographic quality that emphasises their status rather than their distinct personalities.25

It was lucky the family was so rich, since the Braganzas had to bring their own furniture to Lisbon, as well as subsidise the war effort. The Ribeira Palace, on the shores of the sprawling Tagus – the river that was the source of Lisbon’s wealth – was a vast edifice, added to under Philip’s rule. Other than the lack of marble, it was very similar to the Vila Viçosa: a huge, symmetrical building, its many windows reflecting the sky and the river, fronted by an enormous square where festivities and ceremonies took place.

Though the palace itself was architecturally unexciting, the interiors of Lisbon drew the eye. As the Venetian ambassadors recorded: ‘Lisbon doesn’t possess any nobleman’s or bourgeois palace that deserves attention; the buildings are merely very big without any worthy particularity, except for the way in which the Portuguese decorate them, so that they become truly magnificent, with the chambers lined in winter with satins, damasks, and with the finest tapestries.’26

Visitors also noted the city’s cosmopolitan nature, with different cultures doing strange things like eating bananas. There were many slaves, alongside also free Moorish traders, Ethiopian Christians (Ethiopia and Portugal had a special relationship, the kings of Portugal petitioning for Ethiopian Christianity to be recognised by the Pope), and blonde English and Dutch traders, all mingling with native Portuguese and Moors still present after the Reconquista of the peninsula.27

Catherine lived a very sheltered life. It is perhaps a slight exaggeration, but when she arrived in England, one eyewitness claimed that ‘she hath hardly been ten times out of the palace in her life’, being ‘bred hugely retired’.28 We know little about her childhood, beyond the fact that her mother watched over her education carefully. It was a style of education that was, by Luisa’s own admission, ‘more useful than pleasant’, with little time for frivolity and much time devoted to religion.29 Catherine at least turned out more literate than her younger brothers, Afonso and Pedro, neither of whom had much time for writing – it’s possible they could barely sign their names. This is an indictment rather than a triumph of Luisa’s parenting style. In not allowing tutors and insisting on educating the children herself, she was taking helicopter parenting to a new level. It led the boys to rebel whenever they could, while Catherine coped by just going along with whatever was asked of her.

Since Castilian influence was still very strong in Portugal, and Luisa was Spanish, many of the texts Catherine studied and the ‘high’ culture she consumed would have been Castilian. However, the reading deemed appropriate for young women was mainly religious; satire and comedy might have bred loose morals.30 Partly thanks to Luisa, Catherine spoke Spanish fluently. In her letters, she also displays at least a smattering of French and Italian, and she picked up English after a few years in the country, though she didn’t learn any Germanic language until she was in her twenties. She and her mother had a very close relationship, Luisa keeping careful watch over all aspects of her upbringing.

In a letter written to Catherine soon after she left Lisbon in 1662, Luisa signed herself ‘your mother who only idolises you’. Her expressions of love are constant, addressing her daughter as ‘My Catalina’, or ‘My daughter and all my love’, and declaring herself ‘your mother who adores you’.31 We do not have the letters from Catherine to her mother, most likely because of the earthquake-fire-tsunami combination that shattered Lisbon in 1755, but we do know that she loved her mother deeply. Of her younger brothers, Pedro, born in 1648, seems to have been her favourite, much preferred to the awkward Afonso, who had been born in 1643.

The great ceremonials that marked Catherine’s childhood were saints’ days and religious holidays like Corpus Christi, a spring festival celebrating the transubstantiation of Christ’s body into bread and his blood into wine during the Mass. A wafer would be carried through the streets, showcasing Christ’s sacrifice of his body for the world, and in Portugal this grew into one of the biggest processions in Europe, Lisbon’s guilds competing with one another for the grandest procession and the most impressive figures of giants or dragons. Buildings and hastily erected platforms were garlanded with flowers and tapestries, while the smoke from fireworks filled the air.32

Another occasion for celebration and pageantry was the king’s birthday, when his courtiers lined up to kiss his hands in a ceremony called the beija-mão. It was a formal statement of the relationship between king and courtier, confirming João as the source of power and patronage. The same ritual happened every year without fail, performed with punctuality and gusto. For an infanta of Portugal, the court was a predictable space, with nothing to shock or challenge her beyond the normal trials of growing up. Her father’s affairs were discreet, with no mistresses flaunting their power at court. He only had one illegitimate child that we know of, and she was educated far from her half-siblings; they might not even have known about her. Their mother certainly did not believe in noticing such things.

However, even sheltered in the luxurious Ribeira Palace, the life of any member of the ruling family always held the potential for danger, and the future of the Braganza dynasty was far from assured. There was a reason João had wanted to remain in countryside retirement making music.

In August 1641, the first threat to the new regime was discovered. Rather awkwardly for the Braganzas’ reputation for piety, the central conspirator was the pro-Castilian Archbishop of Braga, who had plotted to assassinate João, set fire to the Portuguese fleet and then storm Luisa’s apartments, returning the country to Spanish rule. There are competing tales as to how the plot came to João’s attention, the wildest being that the conspirators employed a Bohemian messenger to carry letters about the rebels’ plans to Spain. One of João’s spies met the Bohemian on the road and, immediately suspecting the poor man, got him drunk, stabbed him and stole the letters. It would have been an incredibly cold-blooded act, and the Bohemian must have been acting in a remarkably suspicious manner. More likely one of the plotters betrayed the affair.

Either way, such an escape, hot on the heels of his miraculously bloodless coup, could only boost João’s reputation for being specially protected by God. A contemporary marvelled, ‘if Heaven had not protected him, there had been but a short space betwixt the Birth and the Grave of his Sovereignty’.33