Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

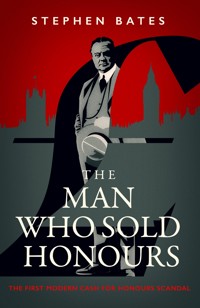

Paying for a peerage - an illegal practice - feels like a very modern form of corruption, one that both the Labour and Conservative parties have been happy to indulge in at times during the early twenty-first century. Except, of course, it was happening almost a century ago. Meet Maundy Gregory, actor, journalist, publishing proprietor, conman, embezzler, MI5 spy - and the man you went to see if you had the money to pay for a peerage in the post-First World War years. Cutting a dash across high society of the 1920s - he was in attendance at the wedding of the future George VI - the immaculately oiled and overdressed Gregory would happily pockets thousands for playing Mr Fixit for wannabe knights and lords, and swell the coffers of Lloyd George's Liberal Party to millions of pounds. Business was brisk, and business was brazen. Visitors to his lavish office on Parliament Street, with a direct line to 'Number 10', would be wined and dined and, after paying up, leave satisfied that they would be next on the list for a knighthood or barony. Nothing could be guaranteed, of course, and it was a strictly no refunds business. But Gregory was also suspected of being something else, to add to his impressive list of accomplishments: a murderer. As the political winds changed, the debts mounted up and the walls closed in around him, he somehow managed to inherit his mistress's not inconsiderable savings when she scribbled a new will on the back of a menu and was suddenly taken ill ... In The Man Who Sold Honours, Stephen Bates lifts the lid on the truth about this long-forgotten character who remains the only person ever to be successfully prosecuted under the sale of honours act of 1925. A powerful preview of the scandals to come in Britain in recent years, this is the story of the original honours tout - a riches-to-rags tale of greed, corruption and murder in the interwar years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK in 2025 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-183773-027-8 eBook: 978-183773-207-4

Text copyright © 2025 Stephen Bates The author has asserted his moral rights.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make acknowledgement on future editions if notified.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India

Printed and bound in the UK

Appointed GPSR EU Representative: Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218 Address: Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, Tallinn, Estonia Contact Details: [email protected], +358 40 500 3575

CONTENTS

Introduction: The Man in the Brown and Yellow Taxi

1.A Land Fit for Heroes

2.Bum Cheeks

3.Mayfair and Town Topics

4.The Chief at War

5.Squiffy and The Goat

6.The Man who Won the War

7.The Honours Tout

8.Honours Abounding

9.An Insult to the Crown

10.Indispensable No More

11.An Act for the Prevention of Abuses

12.The Ambassador Club

13.A Death in the Family

14.Nemesis

15.The Whole Story

16.Monsieur de Gregoire

17.Cash for Honours

Bibliography

Endnotes

INTRODUCTION: THE MAN IN THE BROWN AND YELLOW TAXI

One of the most noted figures in the distinguished pageant of Whitehall.

DAILY EXPRESS, 22 FEBRUARY 1933

Arthur John Peter Michael Maundy Gregory was many things in his life: an actor, teacher, a theatre manager, a newspaper editor, blackmailer, a police informant, a self-proclaimed spy master, a club owner, a hotelier, a prisoner, a bankrupt and an exile, and some of the claims made by and about him were even true. It was lucky he had so many Christian names to cover his multiple identities. But what he was chiefly, memorably and most profitably was an honours tout.

He sold knighthoods and baronetcies for money, and he was rather successful at it. Maundy Gregory indeed may well have sold more honours over a longer period than anyone else has ever done, before or since. Moreover, he was an equal opportunities tout: selling for both the Liberal and Tory parties until the law caught up with him – and only him in the hundred years since the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act of 1925 has been on the statute book. After that he sold papal and other foreign honours instead.

In the years immediately after the First World War, those wealthy and vain enough to wish to add a knighthood to their name could pay a visit to a discreet townhouse at 38 Parliament Street, almost directly opposite the entrance to Downing Street and only a few paces down Whitehall from Parliament itself. They would enter through glass panelled double doors with the words The Whitehall Gazette – Gregory’s paper – picked out in gold lettering. There they would be met by a uniformed usher wearing a livery so very similar to that worn at the time by House of Commons messengers, right down to the brass buttons, that they could be mistaken for their counterparts. They would be escorted upstairs to a waiting room, whose sepulchral calm was enhanced by stained glass windows, before a buzzer would sound and they would be summoned into the presence in the next room of the man who could make their wishes come true.

Maundy Gregory would be sitting on a large red leather upholstered armchair, behind an enormous desk upon which were several telephones and telephone consoles with switches – this at a period when many companies still had no telephones at all – and bell pushes, an array of small coloured electric lights, a Morse tapper key to summon his secretary and a series of red dispatch boxes looking exactly like those government ministries used. On the walls around the room were portraits of the crowned heads – and recently deposed heads – of Europe, all of whom he claimed to know personally. On a side table were signed photographs in silver frames, among them the Duke of York – the future George VI – at whose marriage to Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923 Gregory had been an usher. Next to it was another picture of a famous figure, the Tory politician and former Lord Chancellor Lord Birkenhead – F.E. Smith as he was – who quietly borrowed money from the man he called the Cheerful Giver to subsidise his drinking and gambling debts and underwrite his young mistress, Miss Mona Dunn.

Gregory himself would rise graciously to greet the supplicant. He was slightly below medium height, a little on the portly side, his hair neatly pomaded and parted in the middle. His dress was immaculate – likely a three-piece, purple-shaded suit and a wing-collar to his shirt – and his shoes were highly polished. Around his neck hung a ribbon to which a monocle was attached.

His manner was confiding and softly spoken, almost obsequious, and, as the conversation continued, it was likely that he would, apparently absent-mindedly, pull a large heart-shaped, rose-coloured diamond that was allegedly once the possession of Catherine the Great from his waistcoat pocket and fondle it between his fingers.

The conversation would be desultory, but names would be dropped. Occasionally, the telephone might ring, and he would excuse himself to answer it, confiding that it was ‘Number Ten’ on the line, without admitting that he himself lived at Number Ten, though Hyde Park Terrace, not Downing Street. Ben Pengelly, Gregory’s accountant, suggested that the address had been chosen specifically for that reason.

An anonymous Daily Express correspondent wrote admiringly of Gregory: ‘One met him at Ascot and at the first nights of West End plays whose stars were frequently his intimate friends. One saw him again in Whitehall entering his palatial offices between Scotland Yard and the prime minister’s residence in Downing Street. His distinguished presence would catch the eye at once. The diamond watch chain displayed on a suit of subtle purple was in keeping with his aristocratic features … those who were privileged to visit these offices were always struck by the grave atmosphere of decorum.’1

Getting down to business, Gregory was sure he could help his visitor. The man would likely explain that of course he did not want an honour for himself, but it would please his wife. Gregory would probably intimate that he had heard very good things about the man’s patriotism and sterling business achievements and how he would be only too pleased to be of service. Of course, these things did not come cheap, unfortunately. Wheels needed to be greased to ensure that the name would make it onto the next honours list in a few months’ time, or at the very least the one after that. The normal tariff for a knighthood was £10,000, a baronetcy would be somewhat more: £40,000 because the title could be passed on to one’s heirs and successors.2 Neither gave a right to sit in the House of Lords – peerages were more expensive again at £50,000 – but putting ‘Sir’ in front of one’s name and ‘Lady’ for the wife back at home was not to be sneezed at. The purpose of the sale of titles was to raise money, particularly for the Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s political fund: perhaps those willing to buy a title were not too choosy where their money went. If they were, they could always go to a Conservative honours tout like Harry Shaw.

And, of course, part of the consideration went to Maundy Gregory himself. In the early 1920s, it has been estimated that he was making £30,000 a year in commission,3 six times the salary of a senior cabinet minister of the period. It enabled a comfortable lifestyle, a large apartment in St. John’s Wood (later to become the Abbey Road studios) before moving to the property overlooking the north side of Hyde Park, and, not least, a distinctive brown and yellow taxi and its driver, Tom Bramley. Gregory claimed that the cab was his own, though this seems doubtful since it could not be a licensed taxi and yet employed solely for his personal use, but Bramley did receive a salary. It was useful, he said, for zipping through the London traffic and for escaping from would-be Bolshevik assassins: it even had a peephole cut in the back so he could see if they were being followed. It was not clear why he thought such a taxi would not stand out or be easily spotted in the bustle of London’s black cabs by any terrorist who wanted to bump him off. Probably none did.

Maundy Gregory’s self-image as someone who knew everyone and had easy access to the rich and influential while still operating discreetly in the shadows was one that he obviously liked. He could call up anyone he wanted: dukes and duchesses, exiled kings, the Lord Chancellor himself, government ministers and MPs, the Dean of Westminster Abbey or West End stage stars, and they would take his call. It all fed his ego, and it was no wonder his staff called him the Chief to his face: just the same as the newspaper tycoon, Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the Daily Mail and The Times, was known to his employees at the same time. Naturally, Gregory called his office the Chancellery. It was, said Colin Coote, then a young Liberal MP who wrote articles for Gregory’s newspaper, but much later became editor of The Daily Telegraph, like ‘a cross between Downing Street and MI5’.

Coote left a recollection of his first meeting with Gregory and his modus operandi in his memoirs. It came about probably in 1919 or ’20: ‘I received one day a letter on imposing notepaper headed The Whitehall Gazette asking me to call on the editor and signed “J. Maundy Gregory” … The word “editor” had an irresistible attraction. I called … and was ushered into the presence of an impeccably dressed personage who could not by any possibility live up to his trousers, but who possessed a kind of ingratiating flamboyance. He laid it on with a trowel. “It was always useful for brilliant young politicians to get publicity … if I paid him fifty guineas he would produce a cartoon of me which would be the sensation of Westminster!”

‘I did not need to be told the answer to that one. I said that I had not got fifty guineas but if he would pay me that sum I would write him an article which would be the sensation of the periodicals. This tickled him; to my astonishment he agreed; and to my even greater astonishment he paid. I soon saw that the magazine was a cover for something. Nobody could flaunt so many appurtenances of wealth, including a fountain pen with a twenty-two-carat nib half an inch broad, a taxi perpetually engaged and an infinite capacity for champagne on the profits of a rag like that.’4 A £50 fee then would have been immensely generous for a freelance article – as would its equivalent of more than £2,350 today.

Maundy Gregory would arise late in the morning at his apartment, dress fastidiously – always important to make a good impression – have breakfast served by his housekeeper, Mrs Kate Wells, and then leave quietly through a back entrance where the taxi would be waiting. It was his practice always to leave and arrive unseen, via the garden. A succession of different routes to Whitehall was followed every day, just in case. Maybe the brown and yellow cab would rattle along Oxford Street and down to Whitehall, or else past Marble Arch and Buckingham Palace, along Birdcage Walk to Parliament Square for him to be dropped off at the back of his office. On days when he was not lunching or entertaining in the evening, often at the club he owned, the Ambassador in Conduit Street, Mayfair, Gregory might stay late at work, writing an article for his newspaper The Whitehall Gazette and St. James’s Review or interviewing more clients. On occasions like that, a red light would shine from the office window to indicate that he was not to be disturbed. Would-be supplicants could see it if they stood on the street corner opposite.

Gerald Macmillan, who wrote a biography of Gregory in the 1950s, stated that: ‘His figure might be against him but now that money was no object he set out to clothe and decorate it as best to distract attention from its essential meanness … to many he gave the impression of being too perfectly dressed and of an opulence rather too pretentious, such as would be expected of a nouveau riche.’ He goes on to itemise the highly polished boots, high wing collar, long cuffs and silk tie, gold and jewelled cufflinks and tie pins, never the same set worn two days in a row, gold rings on his fingers and a fresh orchid in his button-hole every day.5

Gregory said – and for once there is no reason to doubt it – that he drank champagne every day, though he once told a dinner guest that he customarily dunked a piece of toast in the glass first to get rid of the bubbles, which seems a rather déclassé thing to do especially as he served vintage Krug.

Gregory’s charm, however, did not work on everyone. The former Scotland Yard detective Superintendent Arthur Askew was still alive when Tom Cullen, author of Maundy Gregory: Purveyor of Honours, interviewed him in the early 1970s. Askew had investigated Gregory in the 1930s, sometime after his prime, into his connection to a possible murder, and he did not like him at all. ‘I have met many villains in my lifetime but none whom I distrusted more than Maundy Gregory,’ he told Cullen. ‘There was an air of the bogus about him. He was too well-dressed, used too much oil on his hair, wore too many rings – one, a green scarab ring had belonged to Oscar Wilde, or so he said. I said to myself: “Hello, here’s a crook, if ever I saw one.”’6

1. A LAND FIT FOR HEROES

What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.

LLOYD GEORGE, SPEECH AT WOLVERHAMPTON, 23 NOVEMBER 1918

What sort of Britain did Maundy Gregory look out upon as his taxi carried him around Belgravia, Westminster and the West End? In the first years after the war, he might well have seen troubling scenes of unrest. The Great War had not only killed 880,000 British service personnel – 6 per cent of the adult population and one in eight of those in the military – and wounded 1.6 million, many grievously for life. But the war’s ending caused a much wider social and economic dislocation. Four million men were discharged and looking for work, three million munitions workers and others engaged in the war effort were now without jobs: 11 per cent of the workforce was unemployed in 1920 and mostly living in abject poverty in squalid conditions.1

Tens of thousands of families were mourning their fathers, brothers, sons and fiancés. The 1921 Census would reveal 109 adult women for every 100 men. The politicians had promised everyone a better life: a ‘land fit for heroes’ would be built, jobs and rates of pay would be restored. But it was not as easy as that.

The latter stages of the war had been accompanied by the worldwide influenza pandemic, the erroneously named Spanish flu, which killed a further 228,000 in Britain, many of them young. It came in waves through 1918 and 1919, infection spreading through the military and to their families, unhindered by a government whose attention was elsewhere and overstretched medical facilities which were unready and, in any case, ill-equipped to deal with the virus. Vaccination was not a possibility, and transmission was not well understood. There were not even enough grave diggers to bury the dead or horses to lead the hearses, and bodies remained unburied for days. It was a cruel and fearful time on top of everything else.2

The mood of anger, grief and disappointment had bubbled up almost as soon as the Armistice had been signed in November 1918. When King George V, mounted and in full dress uniform, inspected a parade of 15,000 wounded soldiers who had already been demobilised in Hyde Park a couple of weeks later, the Prince of Wales – later Edward VIII – said he detected ‘a sullen unresponsiveness’ in the crowd. There were cries of ‘Where is this land fit for heroes?’, and they pushed forward towards the King and crowded round him in gestures not of anger but appeal. It was a tense moment, only a year of so since Czar Nicholas II, the King’s cousin, had been overthrown in the Russian Revolution and less than six months since he and his entire family had been executed by the Bolsheviks. The King rode back to Buckingham Palace from Hyde Park and remarked phlegmatically: ‘Those men were in a funny temper.’ His son, by contrast, wrote: ‘It dawned on me that the country was discontented and disillusioned.’3

That discontent did not manifest itself in revolution as in Russia – as Maundy Gregory and many others obviously feared – but it did produce strikes and demonstrations in the docks, on the railways, among bakers and even, most alarmingly, in the Metropolitan and Liverpool police forces whose pay rates had fallen lower than factory workers and even street sweepers. The strikes were brought off by large pay increases: police pay doubled; and also by speeding up demobilisation, reducing the Army from 3,500,000 to 900,000. Attempts to form trade unions for police and troops were banned by legislation, and the drives to create militant veterans’ groups such as the National Union of Ex-Servicemen were headed off and the organisations replaced by the avowedly non-political British Legion. In any case, most servicemen were not interested in fomenting revolution: they just wanted to get home to their families and resume their old jobs and lives. In the end, the only uprising was in Ireland and the only terrorist incident in England was the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, on his own front doorstep in Eaton Place by two English-born Irishmen, one of whom was hampered in his attempt to escape because he had lost a leg while serving on the Western Front.4

What was more consequential in the longer term were changed social attitudes following the war and the attempted reimposition of an Edwardian social hierarchy. There were drastic economic changes during and after the war for the landowning and aristocratic classes, and many of them found themselves considerably worse off than they had been before the conflict. Those living off investments, as most did, found their incomes eaten away by inflation, and taxes remained much higher than earlier to pay off the war debts: one study suggests that an average estate’s taxes which took 4 per cent of its income in 1914, absorbed 25 per cent by 1919. An agricultural slump reduced incomes further, and many landed families had lost their sons and heirs during the war. The young subalterns, who had led their men over the top on the Western Front, suffered proportionately worse than the ranks of enlisted men. The overall death rate of all troops during the war has been calculated at 11.5 per cent, but of officers who had been educated at Oxbridge in the four years before the start of the war, the comparable statistics were 29 per cent of Oxonians and 26 per cent of those who had been at Cambridge, bearing in mind that almost all of them had become officers (only 3 per cent of the 1,000 Balliol men who joined up served in the ranks.) Approximately 19 per cent of peers under the age of 50 who served were killed.5

It has been estimated that a quarter of all the land in Britain changed hands in the four years between 1918 and 1922.6 The old, landed families were not exactly dying out, but they were not flourishing and were retreating from the shires to their townhouses in London. In their place, in the seats of power at Westminster, would come the men who Stanley Baldwin famously described in 1918 as ‘a lot of hard-faced men who look as if they had done very well out of the war’.7

The affluent class expanded as a result of the war. In the words of the historian Gerard DeGroot:

‘If we include in the upper class those with the means to mimic its ways, we can see how the class expanded during the war. A significant number of men made vast fortunes. Lloyd George’s tendency to draft business leaders into politics gave them the essential ingredient of service to the state which had always distinguished members of the upper class … the composition of the upper class changed, but its essential nature, its position in society and its power remained fundamentally intact.’8

That, of course, was where the sale of honours came in.

The war had other consequences. There was an expansion of middle-class, white-collar jobs, from 12 to 22 per cent of the work force between 1911 and 1921. Such workers were drawn from the section of the population who had volunteered most enthusiastically to join up and had suffered consequently more heavy casualties. Now that the war was ended, to personal and family grief was added a sense of resentment that their status was being reduced and disregarded. The same thing happened to the millions of young women who had volunteered for war work but then found themselves out of jobs when the men came back.

The old pre-war social deference had been eroded in the trenches and would not be restored. As Arthur Gleason, an American journalist, recorded: ‘An old Oxford friend said sadly to me: “Ten years ago when I came into a crowded bus, a working man would rise and touch his cap and give me his seat. I am sorry to see that spirit dying out.”’ Deference might have been slowly expiring, but the old social order remained unchallenged.

Shortages of officers as the war ground on led to the promotion of men from the middle classes to fill the gaps: grammar schoolboys and non-university men replacing all those higher-class subalterns who had been killed. To ensure they did not get above themselves, such men were given the demeaning status of ‘temporary gentlemen’. They were, according to the war poet Wilfred Owen when he wrote home to his mother, ‘privates and sergeants in masquerade’, which was rich considering he himself was the son of a Shropshire station master and had been educated at the Birkenhead Institute. Alfred Burrage, an author of cheap fiction who had been educated at a minor public school, was also dismissive: ‘Judging by the manners and accents … they were nearly all “Smiffs”, late of Little Buggington Grammar School who had been “clurks” in civil life.’

After the war, the ‘Smiffs’ found they were expected to revert to their old status as non-gentlemen: they had only been promoted on sufferance. ‘I try hard to remind myself that the three stars which I now wear are only the temporary marks of proficiency that the war will in ending wipe out and that I will step back into that drab old life,’ wrote one captain, who had been a pre-war salesman. Another added: ‘We have got to wipe this “war record” clear off our minds, drop the “captain” and “lieutenant” … and regard ourselves as fit young civilians who have had a “jolly fine holiday” for four years.’9 Nevertheless, it seems many did retain their wartime ranks to prove that they had once been officers and gentlemen. Think drunken Captain Grimes, one of the schoolmasters in Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall,first published in 1928, though Grimes of course also claimed to have been an Old Harrovian – there were numerous other examples, too, in fiction and in real life.

Almost perversely, as if to rub in the temporary nature of gentlemanly status, those who had been officers found they received neither rehabilitation nor training to reintegrate into civilian life, nor were they entitled to unemployment compensation, or to use a labour exchange to seek work. ‘When it is borne in mind that in a very large number of cases this class of officer did not ask for a commission but was nominated by his commanding officer the fact that he should be worse treated on discharge than if he had remained in the ranks seems almost impossible to defend,’10 wrote one researcher.

Many temporary gentlemen must have found themselves in the same position as George Coppard, who was unemployed after leaving the army aged only 21. Coppard had enlisted at the age of sixteen in 1914, served as a machine gunner on the Western Front for much of the war, and would have been promoted to sergeant had he not been seriously wounded. He wrote in his memoirs 50 years later: ‘Although an expert machine gunner, I was a numbskull so far as any trade or craft was concerned. Lloyd George and company had been full of big talk about making the country fit for heroes to live in, but it was just so much hot air. No practical steps were taken to rehabilitate the broad mass of demobbed men and I joined the queues for jobs as messengers, window cleaners and scullions. It was a complete letdown for thousands like me … there were no jobs for the heroes who haunted the billiard halls as I did … it was a common sight in London to see ex-officers with barrel organs, endeavouring to earn a living as beggars.’11

About a quarter of those returning to civilian life had disabilities for which pensions of up to 25 shillings a week were payable (£1.25 in modern parlance, equivalent to £58 a week in notional spending power), with an extra 2/6d for each dependent child (approximately £5.80) – but recipients had to be severely disabled to qualify for this: those with single missing limbs received less, and those with not immediately visible injuries such as shell shock (now known more widely as PTSD: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) did not qualify at all. The size of such pensions also depended on the rank of the claimant and the generosity of the board making the award, conscious that the rules erred on the side of cruelty. Wounds, mental or physical, which emerged after the war generally did not count and women who married injured former servicemen were not entitled to widows’ pensions if he subsequently died from his wounds: it being held that they ought to have known better than to marry a wounded soldier at the time.

Such living conditions were a world away from the hard-faced men who had done well out of the war, the men to whom Maundy Gregory was selling honours for sums that would have taken a lifetime to earn for the people on the street. Some of these would-be honourands were men who were not even temporarily gentlemen: they just had money to spare. Gregory himself had had what the veterans would have called a cushy billet in England, though he had at least joined up. Did he ever think of the war’s victims as Tom Bramley steered his taxi through the streets of central London each morning, past men wearing their medals as they played their barrel organs on the corners of Oxford Street and Piccadilly, or the disabled ex-servicemen who were steering their bath chairs down Whitehall? The money he was accumulating for the Prime Minister’s political campaigns was going precisely to telling voters like them that the land was indeed fit for heroes.

2. BUM CHEEKS

His well-known red carnation buttonhole and a smile that will not wear off are personal hallmarks which conceal a disconcerting shrewdness.

CHARACTER SKETCH, PROBABLY WRITTEN BY GREGORY HIMSELF, INWHAT’S ONMAGAZINE, SEPTEMBER 1907

Gregory always claimed, somewhat improbably, to have been descended from a line of at least eight English kings that stretched back to William the Conqueror on his mother’s side and even had a four-foot long scroll to justify his lineage, compiled by the College of Heralds and signed by Garter King of Arms. The pedigree apparently took in both John of Gaunt and Harry Percy, who rebelled against Gaunt’s son Henry IV and died at the battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. Indeed, Gregory’s mother, Ursula, did have aristocratic connections, being a cousin of the Vernon family whose recent scion Robert Vernon had been elevated to the peerage as Lord Lyvedon in 1858.1 She was the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel George Wynell Mayow of the 4th Dragoon Guards, who had survived the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava.

Hers was clearly a more distinguished family than that of her husband, the Rev. Francis Maundy Gregory, who became vicar of St. Michael’s parish church in the middle of Southampton in 1870 and remained there until his death nearly thirty years later. It was, however, scarcely a rich parish and the stipend of £183 a year was low for such a benefice. The church, right in the middle of the Old Town, near to the docks, still dominates the landscape with its 165-foot high steeple, the top of which was added during Gregory’s incumbency. By the late nineteenth century, the building had been renovated, but the arrival of a High Church Tractarian Anglican vicar, appointed by the Lord Chancellor with scant regard to the decidedly low church character of the parish, was a source of considerable controversy.

It was only two decades since the church vestry had petitioned Queen Victoria to put down the pretensions of the Pope and remove clergy who would destroy the great principles of the Reformation, but the new priest not only wore vestments at services and a black cassock and Canterbury cap2 when walking round the parish but also introduced papistical practices in church such as holy days of obligation. In the doctrinal furore of the Victorian Church, this was heretical stuff and some priests even went to jail for reintroducing the old traditions. The Southampton Times in September 1870 noted disapprovingly that Gregory had turned his back towards the congregation in reciting the Apostles’ Creed at services, preached in a white surplice and ‘contrary to all precedent here’ pronounced the benediction from the communion rail. Gregory was met with whispers of disapproval, heckled in the street and threatened with violence, but gradually seems to have won at least some of his parishioners round with his sincerity and pastoral care.

What Ursula Maundy Gregory thought of her husband’s calling is hard to say. She had left an agreeable family estate at Old Park, Devizes in Wiltshire to marry an impoverished clergyman and live in a rough, rowdy and unwelcoming town centre parish. There, she gave birth to four sons: the eldest, Michael, died of acute bronchitis aged nine in 1882; another son, Edward, was born in 1875; Arthur came along on 1 July 1877 to be followed by Stephen two years later. If not wealthy, their father’s stipend still allowed for the employment of a maid and cook and to have the boys educated at a local private day school.3

Banister Court in the Southampton suburbs was a large Georgian villa in substantial grounds which had been leased as a school for the sons of merchant navy officers in 1867 and clearly took a muscular attitude to games and physical development which would be suitable for their future careers at sea. Admiral Jellicoe, the future Commander of the Fleet during the First World War, was an old boy. Such a regimen does not seem to have suited young Arthur at all. He had no interest in games or their effect on the ‘spirited part of a boy’s nature being turned to good whereas it would otherwise expend itself in evil’, in the words of its headmaster Christopher Ellaby. Consequently, the young Gregory appears to have been bullied and was nicknamed ‘Bum Cheeks’, in reference to his rubicund, hamster-like facial features, and ‘Pope Lover’ because of his father’s reputation.4

The school did, however, bestow one long friendship in the shape of another local vicar’s son called Harold Davidson, a diminutive figure, who, inevitably, was nicknamed Jumbo, and who would grow up to be one of the most notorious, though irresistibly comic, figures of the 1930s. It was indeed an extraordinary coincidence that one small school should produce two such men at the same time. Davidson went on to graduate from Oxford, be ordained and become for many years the rector of the Norfolk coastal village of Stiffkey, from where he was ousted and defrocked in the early 1930s for alleged immorality to the evident entertainment of the newspaper-reading public. For many years he had deserted the parish every week to catch the train down to London and befriend showgirls, sex workers and waitresses in order to rescue them from the danger of immorality, before returning to his parish briefly only on Sundays to conduct services. Davidson liked to think of himself as the prostitutes’ padre and inevitably fell foul of the local squirearchy, his naivety (and probable chastity) no protection from the majesty of the Church of England and the prurience of the national press. After being defrocked he would turn to preaching from the inside of a barrel on Blackpool pier and come to a sticky end in 1937 in the jaws of an elderly circus lion named Freddie, who he somehow annoyed while preaching as a modern Daniel from inside his cage at a showground in Skegness. He likely trod on the lion’s tail. The classical Christian martyrdom it was said at the time.

That was all many years away in the mid-1890s, when Gregory and Davidson bonded over a joint love of the theatre, though the latter was eventually removed to complete his studies at Whitgift School in Croydon. Davidson, who sounds like the more charismatic performer, used his enthusiasm as a drawing room entertainer, performing comic songs and routines at supper parties successfully enough to fund his degree at Exeter College, Oxford. Gregory followed him to the university in 1895 as a non-collegiate student,5 apparently to tread in his father’s footsteps towards ordination, but abandoned his degree course in 1899, two terms short of his final examinations, following the death of the Rev. Gregory.

Whether the church ever really appealed as an occupation seems doubtful, but the theatrical element certainly did. He was already emulating Davidson as an after-dinner entertainer while at Oxford, and started writing plays there, one of which is said to have upset his father in his dying months. It was called Self-Condemned and was about a priest who rejects the church and its rituals, hypocrisies, falsehoods and fallibilities, which would have been distressing enough for the Rev. Gregory but was worsened by the fact that his son apparently borrowed his vestments and the church’s sacramental ornaments and artefacts without bothering to ask permission first.6

Self-Condemned was sufficiently well thought of, by Gregory at least, to go on tour, though it went down less well with Northern working-class audiences. The money then ran out and the actors had to make their own ways home. His father’s bequest of a little over £3,300 was not enough to sustain his widow and three now grown-up sons: Ursula ended up in a home for ‘matrons’ or, more strictly, the impoverished widows of former clergymen at Morley College in the cathedral close at Winchester where she lived well into the 1930s, apparently unvisited by her son who could presumably have afforded to set her up in more affluent accommodation if he had wanted to do so. Of the other sons, Edward was an accountant who briefly and unhappily worked with his brother in his theatrical business and Stephen emigrated to Canada and served in the Army during both the Boer and First World Wars, rising from the ranks to become an officer.

Arthur threw in his lot with the theatrical profession, starting with the drawing room entertainments, including comic monologues, readings from Dickens, songs, turns at the piano and as ‘Signor Gregorio, ventriloquist and his talking dolls’. And it was in doing this that he got his first big break, which came when he met and befriended a family called Loraine who lived at Yew Tree Cottage at Lyndhurst in the New Forest, a dozen miles outside Southampton.

The Loraines had theatrical connections: the three daughters of the family, Ida, Vivien and Florence, were all stage struck, but more importantly they were related to a professional actor-manager called Harry Loraine and his son, Robert, who was already starring as a leading man in the West End, despite being only eighteen months older than Gregory. Apart from appearing in Shakespeare and Strindberg productions, Robert would go on to star as Jack Tanner in the first London production of Shaw’s Man and Superman – the Don Juan role – in 1905. He had also gone out to South Africa as a volunteer to fight the Boers, temporarily giving up his stage career, and he would later become a pioneer aviator, the first man to fly between Britain and Ireland in 1910 in a Farman III biplane.

There may be a hint that the Loraines in Lyndhurst were quite keen to get rid of the importunate young Gregory, since he kept borrowing money from them and neglecting to pay it back. They were only small loans of a few shillings but mounted up until one of the daughters accompanied him to the shops and pretended that she had no money, so he had to stump up. Gregory was known in the family as ‘Oh, Mabel’ after one of his performance catchphrases.7 It was also perhaps a comment on his character. If that was the tactic it does not seem to have taught the young man a lesson: in later years those who loaned him money rarely got it back. As one of his subordinates said in 1933, ‘Once we get money, we never return it.’

Probably through Harry Loraine, Gregory got taken on by the Ben Greet Players, a touring company, in 1900, which was no mean break because Greet was one of the leading actor managers of the day, specialising in the classical repertoire, from Shakespeare to melodramas, and pioneering open air theatre productions: he would be knighted in 1929 for his work in schools. Despite this and an early part as a comic butler in a play called The Brixton Burglary, Gregory did not stay with Greet for long. He claimed later to have toured under eighteen different managements, seemingly in five years, since he then became the manager of the Prince of Wales Theatre, a burlesque and pantomime house in Southampton, but that didn’t last long either.

By 1903, he had set himself up as an agent for would-be dramatists, though that was a struggle, too, and he was soon back on the stage working for an Irish-American manager called William Wallace Kelly, playing the wily Prince Talleyrand in a play called A Royal Divorce by the Irish dramatist William Gorman Wills about the Emperor Napoleon’s love life. If Talleyrand did not give him insights into deviousness and double-dealing, then Kelly certainly seems to have done so with his talent for hustling and self-promotion. Apparently, Kelly would plaster the towns where the show was being presented with posters telling the audience to choose sides between the Empress Josephine (played by Mrs Kelly, the actress Edith Cole) and her rival Marie-Louise, Bonaparte’s mistress and second wife, resulting in cheers from audiences for Josephine and boos for the unfortunate actress playing Marie-Louise. Cullen says that Kelly was an early master of the Madison Avenue advertising technique of ‘selling the sizzle, not the steak’.8 Nonetheless, Gregory’s engagement lasted only six months, and he left, perhaps after a disagreement. But probably he had learned some useful non-theatrical lessons for the future.

Gregory was certainly hustling as he went from company to company, cast to cast, playing small character parts as the companies he was engaged by and the venues they toured grew bigger. From small seaside resorts to larger city venues in Birmingham, Manchester and then the suburban London circuit such as the Duchess Theatre, Balham, and the Grand at Woolwich. In June 1903, his mother’s cousin, Percy Vernon, the third Baron Lyveden, who was himself an actor (having dropped his first name, Courtenay), secured Gregory an interview with one of the most prestigious of the touring troupes, the Frank Benson company. Frank Benson was a name to conjure with, partly for the modesty of his own acting ability but much more importantly for his enthusiastic commitment to tour Shakespeare around the country and particularly at Stratford-upon-Avon, where his company’s summer residencies made them a predecessor of the Royal Shakespeare Company. Many former Bensonians went on over the years to become stars in their own right, including Isadora Duncan, Henry Ainley, Harcourt Williams and Nigel Playfair. While there may only be an apocryphal basis for the stories that Benson, a keen sportsman and former Oxford blue himself, liked to recruit actors who were good cricketers and rugby players9 to boost the company’s off duty teams, that could not have been the reason for Gregory’s recruitment. He seems anyway by now to have decided that management rather than acting was more lucrative, and he was appointed manager for the Benson northern company at the steady salary of £5 a week, responsible for organising the venues and paying wages and expenses for the cast around the Lancashire and Yorkshire circuit.

That lasted for about three years until he was suspected by members of the company of misappropriating money. Benson sent Bill Savery, his assistant general manager who had actually hired Gregory, north to Birkenhead to see what was going on. Benson’s biographer reported what happened next: ‘He found that Gregory, a natural poseur, had rented for an office an empty room next door to the theatre. There “to give a good impression”, he explained airily, he had distributed about the room ten letter baskets. Although as Savery knew well, he received a salary of five pounds a week, he had a buttonhole, a rose or an orchid, sent up daily by train from Covent Garden. A cabman in a shiny silk hat would meet the buttonhole at the station, carry it back to Gregory and drive him in full evening dress to the theatre where he had reserved the best box. Arriving a little late, Gregory would sit and scrutinise the company – a habit detested by all and especially by one member to whom he proposed marriage three or four times a week. Except for this window dressing, repeated wherever he went, Gregory had nothing to show but disorder. His accounts were in a mess, his writing was unreadable.’10 The outcome, of course, was that he was dismissed at once.

Gregory was probably lucky to escape prosecution. As it was, he shamelessly promoted his involvement with the Bensonites the following year. A profile of him in What’s On magazine in September 1907, which he probably wrote himself, brazenly asserted: ‘For some years Mr Maundy Gregory was prominently associated with the Bensonian management and was instrumental … in developing the Benson company into four companies … His well-known red carnation buttonhole and a smile that will not wear off are personal hallmarks, which conceal a disconcerting shrewdness.’11

He was making a habit of skating close to the wind, but he could not be faulted in self-promotion. An article in The Era newspaper earlier that year showed that William Wallace Kelly’s example had not been wasted on him, now he had become an agent: ‘Mr Maundy Gregory is a firm believer in the hustling principle and thinks nothing of dictating in the train 40 or 50 letters to his American manager, who types them all on the journey. He frequently travels the length of England for half an hour’s interview with someone and then gets straight on the train again for another journey which may possibly last through the night.’

The agency for dramatists, operating out of Gregory’s small flat at Burleigh Mansions in St. Martin’s Lane off Charing Cross Road, was in fact not going terribly well. He wore a shirt with a detachable cellulose collar which could be wiped clean, pinned back to the shirt and secured with a bow tie when he was expecting clients. The ‘American manager’ was actually a nineteen-year-old youth named J. Rowland Sales, who Gregory used to get to tap on a broken Underwood typewriter noisily in the bedroom next to the sitting room to give the impression of frenzied activity when there were visitors. Sales was interviewed by Cullen shortly before his death in 1972 and told him how he had answered an advertisement for a manager in The Era and been interviewed in the flat: ‘I remember thinking to myself, oh dear, this is rather dingy for a man of such importance … whenever he was expecting important visitors, potential angels to back his shows or actors he was considering for parts, the stage had to be set to impress them, with cut flowers on the table and so forth.’ Sales told Cullen that Gregory promised him a salary of £5 a week, but he rarely saw more than £3.

Eventually, things seemed to be going better for him as an impresario in conjunction with his brother, Edward. At Christmas 1907, they staged the pantomime Little Red Riding Hood at the Lyceum, Ipswich. It was a big show with a cast of 60 and was billed as ‘The Largest Pantomime Ever Travelled’. Its star was a young girl billed as Barbara Alleyne (her real name was Elise Barbara Alleyne Barrett): ‘the smallest solo dancer in Europe’ playing Baby Innocence in a ballet sequence, and the only problem was that she was too young to be on the stage. The Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act of 1889 forbade youngsters under the age of eleven from appearing in circuses or shows for which admission was charged, and Barbara’s age, eight, quickly came to the notice of the local police. ‘Maundy Gregory knew the law as well as anyone,’ Barbara Benjamin, by then in her mid-seventies, told Cullen at her home in St John’s Wood a decade or so before her death in 1983. ‘But he assured my parents that everything would be all right. I was the hit of the show and got rave notices in the local papers, Unfortunately, this brought my tender years to the notice of the police.’

Gregory was fined £5 by the local magistrates (‘Winsome Barbara … shed tears of anger and disappointment,’ claimed the East Anglian Daily Times)and the show moved on to Peterborough, where Gregory, anxious about the money he had invested in the pantomime, again used Barbara, this time singing from a box by the side of the stage rather than acting or dancing on it. But if he thought that would get round the law, he was mistaken. The police stepped in, and Barbara’s mother withdrew her from the show.

Far from waiting until she was eleven, however, the following Christmas, Barbara, by now nine, got an even bigger billing in a West End play at His Majesty’s Theatre put on by the famous actor manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree. It was called Pinkie and the Fairies,and Barbara was to perform alongside Ellen Terry, one of the biggest stars in the country. This was too big an opportunity for Barbara’s family to miss and, so, to get round the law, they used her older sister’s birth certificate and changed her name to Elise Craven. She was a huge hit: ‘a marvel of Terpsichorean training and cool self-possession,’ said The Era, ‘The Child who earns £100 a week’ headlined another paper.

Maundy Gregory spotted it, however, and decided to engage in a little blackmail, because he knew how old she really was. Barbara Benjamin told Tom Cullen that Gregory’s then secretary, a woman called Audrey Jekyll, called on her mother ostensibly to warn her that the little girl’s welfare was a concern. ‘For a certain consideration – I don’t recall what the exact amount was – she was prepared to forget that I was under-age and using a forged birth certificate. After a stormy passage Miss Jekyll left the house empty-handed, for my mother was a very astute woman.’ Mrs Barrett was prepared to play that game, too: ‘What she did was threaten to expose Maundy Gregory if anything was said about my age. There was no doubt in her mind that the blackmail scheme had originated with Gregory who had put Miss Jekyll up to the whole unsavoury business.’

Gregory must have been desperate for money even to try such a scheme, but it would have been about then that he fell in once more with Harold Davidson, the vicar of Stiffkey, who apart from his mission to rescue fallen actresses and waitresses in the West End had also become chaplain of the Actors’ Church Union, based at St. Paul’s, the actors’ church in Covent Garden, in 1906. As such, he had a wide circle of contacts, aristocratic, ecclesiastical (the Bishop of London had conducted his wedding to his wife Molly) and theatrical, and he advised his friend how to make contacts with potential investors for his shows on his own account.

Mr Sales told Cullen that he came to know Davidson very well. Gregory always insisted that he was eccentric and naïve, not a sexual predator or abuser. ‘Believe me he was entirely innocent of any immorality with those girls he was accused of consorting with. He only wanted to help them. He was the most generous and kind-hearted man I ever met. We would walk into the Lyons Corner House [then a well-known chain of tea shops] in the Strand and right away Davidson would accost some pretty waitress with: “What is a lovely girl like you doing here? With your looks you should be on the stage.” He meant it. He got many of these girls walk-on parts by badgering the theatrical producers.’12 Sales said he also took some of them back to stay at the vicarage in Stiffkey, proof that Molly knew all about his activities in London.

Davidson’s strategy to boost Gregory’s career was to pick up a telephone and call Wyndham’s Theatre, asking for a box to be reserved for him that evening because the well-known theatrical producer would be entertaining the Duchess of Somerset.13 When Gregory protested that he did not even know the Duchess, Davidson told him: ‘You will, my boy, you will. Like all the aristocracy, she’s simply mad about the theatre … if you want to attract investors it’s important that you be seen in such company.’

The result of such networking was the launch of a company called Combine Attractions Syndicate, in which Gregory was managing director and Davidson was its main fundraiser and promoter, and the object was to import stage hits from the US to tour the British provincial theatre circuit. The first project was to have been a play called Cleopatra by the 27-year-old British dramatist Reginald Kennedy-Cox, which would have featured the glamorous young starlet and Gaiety Girl Ruby Miller in the title role, but that never got off the ground.

Gregory then turned to a revival of a popular Victorian comic opera called Dorothy and persuaded a matinee idol with the distinctly unromantic name of Charles Hayden Coffin to star in the production, though other commitments meant he could only do so for a limited period. The original production had run for three years following its premiere in 1886 – the longest in West End history to that point, far exceeding the contemporary Gilbert and Sullivan operas – and its signature song, Queen of My Heart,