Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

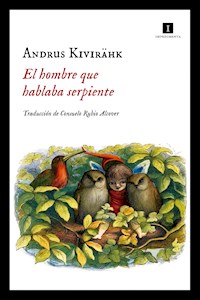

Unfortunately people and tribes degenerate. They lose their teeth, forget their language, until finally they're bending meekly on the fields and cutting straw with a scythe. Leemut, a young boy growing up in the forest, is content living with his hunter-gatherer family. But when incomprehensible outsiders arrive aboard ships and settle nearby, with an intriguing new religion, the forest begins to empty - people are moving to the village and breaking their backs tilling fields to make bread. Meanwhile, Leemut and the last forest-dwelling humans refuse to adapt: with bare-bottomed primates and their love of ancient traditions, promiscuous bears, and a single giant louse, they live in shacks, keep wolves, and speak to snakes. Told with moving and satirical prose, The Man Who Spoke Snakish is a fiercely imaginative allegory about a boy, and a nation, standing on the brink of dramatic change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 652

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

The Man Who Spoke Snakish

Andrus Kivirähk

Translated by Christopher Moseley

First published in the United States of America in 2015 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © Andrus Kivirähk, 2007

Translation copyright © Christopher Moseley, 2015

The moral right of Andrus Kivirähk to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Christopher Moseley to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

This book has been published with permission of Le Tripode, 16 rue Charlemagne 75004 Paris, France. The book was first published in Estonia by Eesti Keele Shihtasutus under the title Mees, kes teadis ussisõnu.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 539 5

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 960 7

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Back Cover

One

he forest has been left empty. These days you hardly meet anyone, apart from the dung beetles, of course. Nothing seems to affect them; they go on humming and buzzing, just as before. They fly to suck blood or bite, or perhaps climb absurdly on your leg if you get in their way, and scurry hither and thither until you wipe them off or flick them away. Their world is just as it was—but it won’t stay that way. The bell will toll even for the dung beetles! Of course I won’t see that day; no one will. But one day that hour will strike. I know that quite certainly.

I don’t go out much anymore, only about once a week do I go above ground. I go to the well; I fetch water. I wash myself and my companion; I scrub his hot body. It uses a lot of water—I have to go to the well several times a day—but it rarely happens that I meet anyone on the path that I might chat to. Not often a human, anyway; a couple of times I’ve met a buck or a boar. They’ve become timid. They’re even afraid of my scent. If I hiss, they stiffen on the spot, glare at me stupidly, but they never come close. They stare as if at a miracle of nature—a human who knows the language of Snakish. This drives them into even greater terror. They would like to butt me into the bushes, give me a wound in the legs, and run as far as possible from this strange freak—but they daren’t. The words forbid it. I hiss at them again, louder this time. With a gruff command I force them to come to me. The beasts low despondently, dragging themselves reluctantly in my direction. I could take pity on them and let them go, but what for? Inside me there is a strange hatred toward the newcomers who don’t know the old ways and just gambol through the forest, as if it had been created at the dawn of time just for them to loll about in. So I hiss a third time, and this time my words are as strong as a quagmire from which it’s impossible to escape. The crazed animals rush toward me as if shot from a bow, while all their innards burst with unbearable tension. They are torn apart, like the tearing of trousers that are too tight, and their intestines spill out onto the grass. It’s disgusting to see, and I get no pleasure from it, but nevertheless I can never let my powers go untested. It’s not my fault that these beasts have forgotten the words of snakes that my ancestors used to teach them.

One time it went differently, however. I was just coming back from the well, a heavy skinful of water on my shoulder, when all at once I saw a big deer on my path. I instantly hissed some simple words, already feeling scorn for the deer’s plight. But the deer didn’t flinch when it heard long-forgotten words of command issuing unexpectedly from the mouth of a man-child. In fact he lowered his head and came up to me, got down on his knees and submissively offered his neck, just as in the old days, when we used to get our food this way—by calling the deer to be killed. How often as a little boy I had seen my mother getting winter provisions for our family in this way! She would select the most suitable cow from the big herd of deer, call her over, and then lightly slit the throat of the submissive animal, hissing snake-words at her. A fully grown deer cow would last us a whole winter. How ridiculous the villagers’ foolish hunting seemed compared to our simple way of getting food. They would spend hours chasing one deer, firing many arrows haphazardly into the bushes, and then afterward, often as not, going home empty-handed and disappointed. All you needed to get a deer to submit to you were a few words! Words that I had just used. A big strong deer was lying at my feet, just waiting. I could have killed it with a single movement of my hand. But I didn’t.

Instead I took the waterskin off my shoulder and offered the deer a drink. He lapped it meekly. He was an old bull, quite old. He must have been; otherwise he would not have remembered how a deer should behave when called by a human. He would have struggled and grappled, tried to get to the treetops, perhaps using his teeth, even as the ancient force of the words drew him to me; he would have come to me like a fool, whereas now he came to me like a king. No matter that he was coming to be slaughtered. Even that is a skill to be learned. Is there anything humiliating about submitting yourself to age-old laws and customs? Not in my opinion. We never killed a single deer for fun. What fun is there to be had in that? We needed to eat, there was a word that would get food for you, and the deer knew that word and obeyed it. What is humiliating is to forget everything, like those young boars and bucks, who take fright when they hear the words. Or the villagers, who would go out in their dozens just to catch one deer. It is stupidity that is humiliating, not wisdom.

I gave the deer a drink and stroked his head and he rubbed his muzzle against my jacket. So the old world had not completely vanished after all. As long as I’m alive, as long as that old deer is alive, Snakish will still be known and remembered around these parts.

I let the deer go. May he live long. And remember.

What I was actually going to tell a story about was the funeral of Manivald. I was six years old at the time. I had never seen Manivald with my own eyes, because he didn’t live in the forest, but by the sea. To this day I don’t actually know why Uncle Vootele took me with him to the funeral. There were no other children there. My friend Pärtel wasn’t there, nor was Hiie. But Hiie had definitely been born by then; she was only a year younger than me. Why didn’t Tambet and Mall take her with them? It was after all for them just a pleasant occasion—not in the sense that they had anything against Manivald or that his death would bring them pleasure. No, far from it. Tambet respected Manivald very much; I clearly remember what he said at the funeral pyre: “Men like that are not born anymore.” He was right; they weren’t. In fact no men at all were being born anymore, at least not in our district. I was the last; a couple of months before me there was Pärtel; a year later Tambet and Mall had Hiie. She wasn’t a man; she was a girl. After Hiie, only weasels and hares were born in the forest.

Of course Tambet didn’t know that at the time, nor did he want to. He always believed that the old times would come again, and so on. He couldn’t believe otherwise; that’s the kind of man he was, strongly loyal to all the ways and customs. Every week he would go to the sacred grove and tie colored strips of cloth to a linden tree, believing he was making a sacrifice to the nature spirits. Ülgas, the Sage of the Grove, was his best friend. Actually, the word “friend” isn’t right; Tambet wouldn’t have called him his friend. That would have seemed the height of boorishness to the sage. He was great and holy, and had to be respected, not befriended.

Naturally Ülgas was also at Manivald’s funeral. How could he not be? He was the one who had to light the funeral pyre and accompany the soul of the departed to the spirit world. He did this at annoying length: he sang, he beat a drum, he burned some mushrooms and straw. That was how the dead had been cremated from age to age; that was what had to be done. That is why I say that that funeral was very much to Tambet’s taste. He liked all sorts of rituals. As long as things were done the way his forefathers had done them, Tambet was happy.

Afterward, I felt terribly sad; I remember it clearly. I didn’t know Manivald at all, so I couldn’t have been grieving; all the same, I was just gazing around me. At first it was exciting to see the dead man’s wrinkled face with its long beard—and quite gruesome too, because I’d never seen a dead person before. The sage’s incantations and conjurations went on so long that in the end it was no longer either exciting or terrifying. I would just as soon have run away—to the seashore, since I’d never been there before. I was a child of the forest. But Uncle Vootele kept me there, whispering in my ear that soon they’d be lighting the pyre. At first it was impressive, and I did want to see the fire, especially how it burns a man up. What would come out of him? What kind of bones did he have? I stayed on the spot, but Ülgas the Sage carried on with his never-ending observances and in the end I was half dead with boredom. It wouldn’t even have interested me if Uncle Vootele had promised to flay the corpse before burning; I just wanted to go home. I yawned audibly, and Tambet glared at me with his goggle-eyes and growled, “Quiet, boy, you’re at a funeral! Listen to the sage!”

“Go on, run around!” Uncle Vootele whispered to me. I ran to the seashore and jumped into the waves fully clothed; then I played with the sand, until I looked like a lump of mud. Then I noticed that the bonfire was already burning, and I ran back to the fire at top speed, but there was no sign left of Manivald. The flames were so big they rose up to the stars.

“How filthy you are!” said Uncle Vootele, trying to wipe me clean with his sleeve. Again I met Tambet’s fierce gaze, because obviously it wasn’t the done thing to behave at funerals as I was, and Tambet was always very particular about observing the rules.

I didn’t care about Tambet, because he wasn’t my father or uncle, just a neighbor who was fierce but didn’t have any power over me. I tugged at Uncle Vootele’s beard and demanded, “Who was Manivald? Why did he live by the sea? Why didn’t he live in the forest like us?”

“His home was by the sea,” replied Uncle Vootele. “Manivald was an old, wise man. The oldest of us all. He had even seen the Frog of the North.”

“Who was the Frog of the North?” I asked.

“The Frog of the North is a great snake, the biggest of all, much bigger than the king of the snakes. He is as big as a forest and he can fly. He has enormous wings. When he rises in the air, he covers the sun and the moon. In ancient times he used to rise often in the sky and devour all our enemies who came to that shore in their boats. And after he had devoured them, we took their possessions. So we were rich and powerful. We were feared, because no one got out alive from that coast. They also knew that we were rich, and their greed overcame their fear. More and more boats sailed to our shore to steal our treasures, and the Frog of the North killed them all.”

“I want to see the Frog of the North too,” I said.

“I’m afraid you can’t anymore,” sighed Uncle Vootele. “The Frog of the North is asleep and we can’t wake him up. There are too few of us.”

“One day we will!” said Tambet. “Don’t talk like that, Vootele! What kind of defeatist nonsense is that? Mark my words. We will see the day when the Frog of the North rises in the sky and eats up all the paltry iron men and village rats!”

“You’re talking nonsense,” said Uncle Vootele. “How is that supposed to happen, when you know very well that it would take at least ten thousand men to wake up the Frog of the North? Only when ten thousand men together say the snake-words will the Frog of the North wake up from his secret nest and rise up under the sky. Where are those ten thousand? We can’t even get ten together!”

“You must not give in!” hissed Tambet. “Look at Manivald. He was always hopeful and did his duty every day! Every time he noticed a ship on the horizon, he would set a dry stump alight, to announce to everyone: ‘It’s time for the Frog of the North to wake!’ Year after year he did that, even though no one had answered his call for ages, and the alien boats would land and the iron men came ashore with impunity. But he didn’t smite with his fist. He just went on pulling up stumps and drying them out, lighting them up and waiting—just waiting! He was waiting for the Frog of the North to come in power to the forest once again, as in the good old days!”

“He will never come again,” said Uncle Vootele gloomily.

“I want to see him,” I insisted. “I want to see the Frog of the North!”

“You won’t,” said Uncle Vootele.

“Is he dead?” I asked.

“No, he will never die,” my uncle said. “He’s asleep. I just don’t know where. No one knows.”

Disappointed, I fell silent. The story of the Frog of the North was interesting, but it had a bad ending. What was the use of miraculous things one can never see? Tambet and my uncle carried on arguing while I traipsed back to the seashore. I walked along the beach; it was beautiful and sandy, and here and there large uprooted stumps lay around. They must have been the same ones that the departed and now-immolated Manivald had been drying—to light as beacons that no one heeded. Beside one of the stumps there was a man crouching. It was Meeme. I had never seen him walking, only stretched out under some bush, as if he were a leaf of a tree, carried by the wind from place to place. He was always munching on some fly agaric and always offered some to me too, but I never accepted it, because my mother wouldn’t let me.

This time too, Meeme was on his side beside the stump and again I hadn’t seen when and how he had come. I promised myself that one day I would yet find out what that man looked like standing on two legs and how he moved around at all—upright like a human or on all fours like an animal, or sliding along like a snake. I went closer to Meeme and saw to my surprise that this time he wasn’t eating fly agaric, but sipping some sort of drink from a skin.

“Ahh!” He was just wiping his mouth when I crouched down beside him and sniffed the strange odor wafting from the skin. “It’s wine. Much better than fly agaric, thanks be to those foreigners and their bit of common sense. The mushroom used to make you drink lots of water, but this here quenches your thirst and makes you drunk at the same time. Great stuff! I’ll think I’ll stick with it. Want some?”

“No,” I said. True, my mother hadn’t forbidden me to drink wine, but I could guess that since Meeme offered it, it couldn’t be any better than the fly agaric. “Where do you get skins like that?” I’d never seen anything like it in the forest.

“From the monks and the other foreigners,” replied Meeme. “You just have to smash their heads in—and the skin is yours.” He went on drinking. “Tasty little drink, there’s no denying it. That silly Tambet can yell and squeal all he likes, but the foreigners’ tipple is better than ours.”

“So what was Tambet yelling and squealing about?” I asked.

“Ah, he won’t allow us to have anything to do with the foreigners or even try their things,” said Meeme dismissively. “I did say that it wasn’t I that touched that monk, it was my ax, but he’s still twitching. Well, what if I don’t want to carry on eating fly agaric? I mean this stuff’s much better and goes to your head quicker too … A man has to be flexible, not stiff like this stump here. But that’s what we’re like these days. What use has being stiff been to us? Like the last flies before the winter, we drone our way slowly through the forest, until we slouch into the moss and die.”

I didn’t understand any more of his talk and I got up to go back to my uncle. “Wait, boy!” Meeme stopped me. “I wanted to give you something.”

I started shaking my head vigorously, for I knew that now he would produce some fly agaric or wine or some other disgusting thing.

“Wait, I said!”

“Mother won’t let me!”

“Hold your tongue! Your mother doesn’t even know what I want to give you. Here, take it! I don’t have anything to do with it. Hang it around your neck.”

Meeme thrust into my palm a little leather bag, which seemed to have something small yet heavy inside it.

“What’s in here?” I asked.

“In there? Well, there’s a ring in there.”

I untied the mouth of the bag. Indeed there was a ring in it. A silver ring, with a big red stone. I tried it on, but the ring was too big for my tiny fingers.

“Carry it in the bag. And hang the bag around your neck.”

I put the ring back in the bag. It was made of a strange kind of leather! As thin as a leaf, and if you let it out of your hand, the wind would carry it straight away. But then, a precious ring should have a fine little nest.

“Thank you!” I said, terribly happy. “It’s a really pretty ring!” Meeme laughed.

“You’re welcome, boy,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s beautiful or ugly, but it’s useful. Keep it nicely in the bag like I told you.”

I ran back to the bonfire. Manivald had been burned up by now, only his ashes still smoldered. I showed the ring to Uncle Vootele, and he examined it long and thoroughly.

“It’s a precious thing,” he said at length. “Made in a foreign land and probably reached our shores at one time along with the men of iron. I wouldn’t be surprised if the first owner of this ring was a victim of the Frog of the North. I don’t understand why Meeme chose you to give it to. He could well have sent it to your sister, Salme. What will you do, boy, with an expensive piece of jewelry like that in the forest?”

“I certainly won’t give it to Salme!” I cried, offended.

“No, don’t. Meeme never does anything for no reason. If he gave you the ring, there must be a need for it. Right now I don’t understand his plan, but that doesn’t matter. It’ll all be clear one day. Let’s go home now.”

“Yes, let’s,” I agreed, and realized how sleepy I was. Uncle Vootele lifted me onto a wolf’s back and we went home through the nocturnal forest. Behind us lay the embers of the fire and the sea, no longer watched over by anyone.

Two

n fact I was born in the village, not in the forest. It was my father who decided to move to the village. Everybody was moving, well, almost everybody, and my parents were among the last. That was probably on my mother’s account, because she didn’t like village life; she wasn’t interested in farming and she never ate bread.

“It was slops,” she used to say to me. “You know, Leemet, I don’t believe anybody actually likes it. This bread eating is really just showing off. They want to appear terribly fine and to live like foreigners. But a nice fresh haunch of deer is quite another thing. Now come on and eat, dear child! Who did I roast these joints for?”

My father was obviously of a different opinion. He wanted to be a modern person, and a modern person should live in a village, under the open sky and the sun, not in a murky forest. He should grow rye, work all summer like some filthy ant, so that in autumn he could look important and gobble bread like the foreigners. A modern person was supposed to have a scythe at home, so that in autumn he could stoop down and cut the grain on the ground; he had to have a quern on which to grind the grains, huffing and puffing. Uncle Vootele told me how my father—when he was still living in the forest—would just about explode with irritation and envy when he thought about the interesting life the villagers were leading and the impressive tools they had.

“We must hurry up and move to the village!” he had shouted. “Life is passing us by! These days all normal people live under the open sky, not in the bushes! I want to sow and reap too, as they do everywhere in the developed world! Why should I be any worse? Just look at the iron men and the monks; you can see straight away that they’re a hundred years ahead of us! We must make every effort to catch up with them!”

And so he took my mother to live in the village; they built themselves a little cottage and my father learned to sow and reap and got himself a scythe and a quern. He started going to church and learning German, so he could understand the speech of the iron men and learn even better and more fashionable tricks from them. He ate bread and, smacking his lips, praised its goodness, and as he learned to make proper barley gruel, there was no end to his enthusiasm and pride.

“It tasted like vomit,” my mother confessed to me, but my father ate barley gruel three times a day, screwing up his face a bit, while claiming that it was a particularly dainty dish, for you had to develop a taste. “Not like our hunks of meat, which any fool can gobble, but a proper European food for people with finer tastes!” he would say. “Not too rich, not too fatty, but sort of lean and light. But nourishing! A food for kings!”

When I was born, my father advised that I should be fed only on barley gruel, because his child “has to have the best.” And he got me a sickle, so that as soon as my legs could carry me I would go stooping in the fields with him. “Of course a scythe is a precious thing, and you might think there’s no sense in putting it into a tiny tot’s hands, but I don’t agree with that attitude. Our child ought to get used to modern tools from the start,” he said proudly. “In the future we won’t get by without a scythe, so let him learn the great art of reaping rye straight away!”

All this was related to me by Uncle Vootele. I don’t remember my father. And my mother didn’t like talking about him; every time he came up she would become uneasy and change the subject. She must have blamed herself for my father’s death, and I suppose she was guilty. My mother was bored in the village; she didn’t care for work in the fields, and while my father was striding out to go sowing, my mother was wandering around the old familiar forests, and she got acquainted with a bear. What happened next seems to be quite clear; it’s such a familiar story. Few women can resist a bear; they’re so big, soft, helpless, and furry. And besides that, bears are born seducers, and terribly attracted to human females, so they wouldn’t let slip an opportunity to make their way up to a woman and growl in her ear. In the old days, when most of our people still lived in the forest, there were endless cases of bears becoming women’s lovers, trysts that would ultimately end in the man discovering the couple and sending the brown beast packing.

The bear started visiting us, always when my father was toiling in the field. He was a very friendly animal; my sister, Salme, who is five years older than me, remembers him and has told me that the bear always brought her honey. Like all bears at that time, this bear knew how to talk a little, since bears are the cleverest of animals, of course excepting snakes, the brothers of humans. True, bears couldn’t say much, and their conversation wasn’t very smart—but how smart do you have to be to talk to your lover? At least they could chat nicely about everyday matters.

Of course, everything’s changed now. A couple of times, when carrying water from the spring, I’ve seen bears and shouted a few words of greeting to them. They’ve stared at me with stupid faces and taken off with a crackle into the bushes. That whole stratum of culture they possessed down the long centuries in their dealings with men and snakes has been dissipated in such a short time, and bears have become ordinary animals. Like ourselves. Apart from me, who now knows the snake-words? The world has gone downhill, and even the water from the spring tastes bitter.

But never mind that. In those days, in my childhood, bears were still able to exchange ideas with humans. We were never friends; we considered bears too far below us for that. Ultimately we were the ones they pawed with their honey-paws and pulled at, out of primitive stupidity. In their way they were the pupils of humans, for we were their superiors. And of course we knew the lustfulness of bears, and that incomprehensible attraction that our women felt for them. That was why every man looked on them with a slight suspicion: “That fat furry bundle of love won’t get my woman …” Too often they would find bear fur in their beds.

But things were even worse for my father. He didn’t find only bear fur in the bed; he also found a whole bear. In itself that mightn’t have been so bad; he should have just given the bear a good hiss and the creature, caught in the act, would have slunk off in shame to the forest. But my father had started to forget Snakish, because he didn’t need to speak it in the village, and besides, he didn’t think much of the snake-words, believing that a scythe and a quern would serve him a whole lot better. So when he saw the bear in his own bed, he mumbled some words of German, whereupon the bear—confused by the incomprehensible words, and annoyed at being caught in flagrante—bit his head off.

Naturally he regretted it straight away, because bears are generally not bloodthirsty animals, unlike for example wolves, who will serve humans, carrying them on their backs and allowing themselves to be milked—though only under the influence of the Snakish words. A wolf really is a fairly dangerous domestic animal, but since there is no tastier milk to be had from anyone in the forest, one reconciles oneself to its sullenness, especially as the Snakish words render it as meek as a titmouse. But a bear is a creature with sense. The bear had killed my father in desperation, and since the murder was committed in the heat of passion, he punished himself on the spot and bit his own tool off.

Then my mother and the castrated bear burned my father’s body, and the bear fled deep into the forest, vowing to my mother that they would never meet again. Apparently this was a suitable solution for my mother because, as I said, she felt terribly guilty and her love for the bear ended abruptly. For the rest of her life she couldn’t stand bears, would hiss as soon as she saw them, and in this way she retreated from her former life. This hatred of hers later brought much confusion to our family, and strife too, but I will speak of that later, at the right time.

After my father’s death, my mother saw no reason to stay in the village; she strapped me on her back, took my sister by the hand, and moved back to the forest. Her brother, my uncle Vootele, was still living there, and he took us into his care, helped us to build a hut, and gave us two young wolves, so we would always have fresh milk. Although she was still shocked by my father’s death, she breathed more easily, because she had never wanted to leave the forest. This was where she felt at ease, and she didn’t care a bit that she wasn’t living like the iron men or that there wasn’t a single scythe in the house. In our mother’s home we no longer ate bread, but there were always piles of deer and goat meat.

I wasn’t even one year old when we moved back to the forest. So I knew nothing of the village or the life there; I grew up in the forest and it was my only home. We had a nice hut deep in the woods, where I lived with my mother and sister, and Uncle Vootele’s cave was nearby. In those days the forest was not yet bereft of people. Moving around, you would be bound to meet others—old women milking their wolves in front of their huts, or long-bearded old men, chatting away crudely with the vipers.

There were fewer younger people and their numbers kept decreasing, so that more and more often you would come across an abandoned dwelling. Those huts were vanishing into the undergrowth, ownerless wolves were running around, and the older people said that once you’ve let it go, it’s not really a life for anyone anymore. They were especially distressed that children were not being born anymore, which was quite natural. Who was around to bear them when all the young people were moving to the village? I too went to look at the village, peering from the edge of the forest, not daring to go any closer. Everything there was so different, and a lot smarter too I thought. There was plenty of sunlight and open space, the houses under the open sky seemed a lot nicer to me than our hovel, half-buried in the spruce trees, and in every home I could see big numbers of children scurrying around.

This made me very jealous, for I had few playmates. My sister, Salme, didn’t care much for me. She was five years older, and a girl besides; she had her own things to do. Luckily there was Pärtel, and I ran around with him. And then there was Hiie, Tambet’s daughter, but again she was too small, tottering around her home on stiff legs and falling over every now and then on her bum. She was no company for me at first, and anyway I didn’t like going over to Tambet’s place. I may have been young and stupid but I did understand that Tambet couldn’t stand me. He would always snort and hiss when he saw me, and once, when Pärtel and I were coming from berry picking and, out of the goodness of my heart, I offered a strawberry to Hiie, who was squatting on the grass, Tambet yelled from inside the house: “Hiie, come away from there! We don’t take anything from the village people!”

He could never forgive my family for once leaving the forest, and he stubbornly persisted in regarding me and Salme as villagers. At the sacred grove he always scowled at us with obvious disdain, as if he were offended that stinking village mongrels like us would push our way into such an important place. And I only went to the grove under duress, because I didn’t like the way Ülgas the Sage anointed the trees with hare’s blood. Hares were such dear creatures; I couldn’t understand how anyone could kill them just to sprinkle on the tree roots. I was afraid of Ülgas, although in appearance he wasn’t so horrible; he had a kindly, grandfatherly face, and was good to children. Sometimes he would visit us and talk about all sorts of fairies and about how children in particular should show great respect to them, and bring a sacrifice to the water-sprite before washing at the spring, and then another after emptying the water bucket. And when you want to bathe in a river, you should bring a few sacrifices, if you don’t want the water-sprite to drown you.

“What sacrifices should they be?” I asked, and Ülgas the Sage explained, laughing affably, that the best thing to take is a frog, cutting it alive from the head lengthwise and throwing it into the spring or river. Then the sprite is satisfied.

“Why are those sprites so cruel?” I asked, frightened, because torturing a frog like that seemed horrible to me. “Why do they want blood all the time?”

“What rubbish you talk! Sprites aren’t cruel,” said Ülgas, admonishing me. “Fairies are simply the rulers of the waters and the trees, and we should obey their orders and do their bidding; that has always been our custom.”

Then he patted me on the cheek, telling me by all means to come back to the grove soon—”because those who don’t visit the grove will be torn apart by the dogs”—and left. But I was torn by terror and hesitation, because I just couldn’t cut a live frog in half. I bathed very rarely and as close to the shore as possible, so I could scramble out of the water before the bloodthirsty water-sprite, without the propitiation of a frog-corpse, would leap at me on the shore. Even when I did go to the sacred grove, I always felt uncomfortable, looking around everywhere for those horrible dogs that lived there and kept watch, according to Ülgas, but all I met was the withering gaze of Tambet, who no doubt took offense that a “villager” like me was gazing around a sacred place, instead of concentrating on the conjurings of the Sage of the Grove.

Being thought of as a villager didn’t really worry me, because, as I said, I liked the village. I was always pressing my mother to know why we moved away from there and asking if we could go back—if not for good, then at least for a while. Of course my mother wouldn’t agree, and tried to explain to me how nice it was in the forest, and how tedious and hard the life of the village people was.

“They eat bread and barley gruel there,” she would say, clearly wanting to scare me, but I couldn’t remember the taste of either of them, and the words didn’t provoke any disgust in me. On the contrary, those unknown foods sounded alluring; I would have liked to try them. And I told my mother so.

“I want bread and barley gruel!”

“Ah, you don’t know how horrible they are. We’ve got plenty of roast meat! Come and take some, boy! Believe me, it’s a hundred times nicer.”

I didn’t believe her. Roast meat I ate every day; it was ordinary food, with nothing mysterious about it.

“I want bread and barley gruel!” I insisted.

“Leemet, stop talking nonsense now! You don’t even know what you’re saying. You don’t need any bread. You just think you want it, but actually you’d spit it straight out. Bread is as dry as moss; it gets stuck in your mouth. Look, I’ve got owls’ eggs here!”

Owls’ eggs were my favorite, and at the sight of them I stopped whining and set about sucking the eggs empty. Salme came into the room, saw me, and screamed that our mother was spoiling me. She wanted to drink owls’ eggs too!

“But of course, Salme,” said my mother. “I’ve put aside eggs for you. You each get just as many.”

Then Salme grabbed her own eggs, sat down next to me, and we competed with each other. And I no longer thought of bread or barley gruel.

Three

uite naturally, however, a few owls’ eggs couldn’t kill my curiosity for long, and the very next day I was roaming on the edge of the forest, looking greedily toward the village. My friend Pärtel was with me, and it was he who finally said, “Why are we watching from so far away? Let’s sneak a bit closer.”

The suggestion seemed extremely dangerous; the very thought of it made my heart race. Nor did Pärtel look all that brave; he looked at me with an expression that expected me to shake my head and refuse; his words had indicated his dread. I didn’t shake my head; I just said, “Let’s go then.”

As I said it, I had the feeling that I was expected to jump into some dark forest lake. We went a couple of steps and stopped, hesitating; I looked at Pärtel and saw that my friend’s face was as white as a sheet.

“Shall we go on?” he asked.

“I guess so.”

So we did. It was horrible. The first house was already quite close, but luckily no one appeared. Pärtel and I hadn’t agreed how far we would go. As far as the house? And then—should we take a look in the doorway? We surely wouldn’t dare to. Tears overcame me; I would have liked to run headlong back into the forest, but since my friend was walking beside me, it wouldn’t do to look so scared. Pärtel must have been thinking the same thing, because I heard him whimpering now and then. And yet, as if bewitched, we kept inching forward, step by step.

Then a girl came out of the house, about our age. We came to a stop. If some adult had appeared before us, we probably would have made off back to the forest with a loud cry, but there was no need to flee because of a girl of our own age. She didn’t seem very dangerous, even if she was a village child. Nevertheless we were very cautious, staring at her and not going any closer.

The girl looked back at us. She didn’t seem to feel any fear.

“Did you come from the forest?” she asked.

We nodded.

“Have you come to live in the village?”

“No,” replied Pärtel, and I saw my chance to do a bit of bragging, informing her that I had already lived in the village, but moved away.

“Why did you go back to the forest?” The girl was amazed. “Nobody goes back to the forest; they all come from the forest to the village. They’re fools that live in the forest.”

“You’re a fool yourself,” I said.

“No I’m not; you are. Everyone says only fools live in the forest. Look what you’re wearing! Skins! Awful! Like an animal.”

We compared our own clothing with the village girl’s, and we had to admit that the girl was right; our wolf and goat skins really were a lot uglier than hers, and hung off us like bags. The girl, on the other hand, was wearing a long, slim shirt, which was nothing like an animal skin; it was thin, light, and moved in the wind.

“What kind of skin is that?” asked Pärtel.

“It isn’t skin; it’s cloth,” replied the girl. “It’s woven.”

That word meant nothing to us. The girl burst out laughing.

“You don’t know what weaving is?” she shrieked. “Have you even seen a loom? A spinning wheel? Come inside. I’ll show you.”

This invitation was both frightening and alluring. Pärtel and I looked at each other, and we decided that we ought to take the risk. These things with strange names ought to be seen. And whatever that girl might do to us, there were two of us after all. That is, unless she had allies inside …

“Who else is in there?” I asked.

“No one else. I’m alone at home; the others are all making hay.”

That too was an incomprehensible thing, but we didn’t want to appear too stupid, so we nodded as if we understood what “making hay” meant. Our hearts were in our throats as we went inside.

It was an amazing experience. All the strange contraptions that filled the room were a feast for the eyes. We stood as if thunderstruck, and didn’t dare sit down or move. The girl, on the other hand, felt right at home and was delighted to show off in front of us.

“Well, there’s a spinning wheel for you!” she said, patting one of the queerest objects I’ve ever seen in my life. “You spin yarn on it. I can already do it. Want me to show you?”

We mumbled something. The girl sat down at the spinning wheel and immediately a strange gadget started turning and whirring. Pärtel sighed with excitement.

“Mighty!” he muttered.

“You like it?” the girl inquired proudly. “Okay, I can’t do any more spinning just now.” She got up. “What else can I show you? Look, this is a bread shovel.”

The bread shovel, too, made a deep impression on us.

“But what’s that?” I asked, pointing to a cross shape hanging on the wall, to which was attached a human figure.

“That is Jesus Christ, our God,” someone answered. It wasn’t the girl; it was a man’s voice. Pärtel and I were as startled as mice and wanted to rush out the door, but our way was barred.

“Don’t run away!” said the voice. “No need to tremble like that. You’re from the forest, aren’t you? Calm down, now, boys. Nobody means you any harm.”

“This is my father,” said the girl. “What’s wrong with you? Why are you afraid?”

Timidly we eyed the man who had stepped into the room. He was tall, and looked very grand with his golden hair and beard. To our eyes he was also enviably well dressed, wearing the same sort of light-colored shirt as his daughter, the same furry breeches, and around his neck the same figure on a cross that I had seen on the wall.

“Tell me, are there still many people living in the forest?” he asked. “Please do tell your parents to give up their benighted ways! All the sensible people are moving now from the forest to the village. In this day and age it’s silly to go on living in some dark thicket, doing without all the benefits of modern science. It’s pathetic to think of those poor people who still carry on a miserable existence in caves, while others are living in castles and palaces! Why do our folk have to be the last? We want to enjoy the same pleasures that other folk do! Tell that to your fathers and mothers. If they won’t think of themselves, then they ought to show some pity for their children. What will become of you if you don’t learn to talk German and serve Jesus?”

We couldn’t utter a word in response, but strange words like “castles” and “palaces” made our hearts tremble. They must surely be finer things than spinning wheels and bread shovels. We would have liked to see them! We should really talk our parents into letting us spend at least some time in the village, just to look at all these marvels.

“What are your names?” asked the man.

We mumbled our names. The man patted us on the shoulders.

“Pärtel and Leemet—those are heathen names. When you come to live in the village, you’ll be christened, and you’ll get names from the Bible. For instance, my name used to be Vambola, but for many years now I’ve had the name Johannes. And my daughter’s name is Magdaleena. Isn’t that beautiful? Names from the Bible are all beautiful. The whole world uses them, the fine boys and pretty girls from all the great peoples. Us too—the Estonians. The wise man does as other wise men do, and doesn’t just run around berserk like some piglet let out of a pen.”

Johannes patted us on the shoulder once more and led us into the yard.

“Now go home and talk to your parents. And come back soon. All Estonians have to come out of the dark forest, into the sun and the open wind, because those winds carry the wisdom of distant lands to us. I’m an elder of this village. I’ll be expecting you. And Magdaleena will be expecting you too; it would be nice to play with you and go to church on Sunday to pray to God. Till we meet again, farewell, boys! May God protect you!”

Obviously something was troubling Pärtel; he opened his mouth a few times, but didn’t dare utter a sound. Finally, when we really did turn to leave, he couldn’t contain his question any longer: “What is that long stick in your hand? And all those spikes in it!”

“It’s a rake!” replied Johannes with a smile. “When you come to live in the village, you can have one of these!”

Pärtel’s face broke into a smile of joy. We ran into the forest.

For a little while we ran together, then we each scurried off to our own homes. I rushed into the shack, as if someone were chasing me, in the certain knowledge that now I would make it clear to my mother: life in the village was much more interesting than in the forest.

Mother wasn’t at home. Nor was Salme. Only Uncle Vootele was sitting in a corner, nibbling on some dried meat.

“What happened to you?” he asked. “Your face is on fire.”

“I went to the village,” I replied and told him rapidly, gabbling, and sometimes losing my voice with excitement, about everything I had seen in Johannes’s house.

Uncle Vootele did not change his expression on hearing all these marvels, even though I drew a rake for him on the wall with a piece of charcoal.

“I’ve seen a rake, yes,” he said. “It’s no use to us here.”

This seemed to me unbelievably stupid and old-fashioned. How? If something as crazily exciting as a rake has been invented, then it’s definitely of use! Magdaleena’s father Johannes is using it, after all!

“He might really need it, because you can scrape hay together with a rake,” explained Uncle Vootele. But they need to cultivate hay so that their animals won’t die of hunger in winter. We don’t have that problem. Our deer and goats can fend for themselves in winter; they look for their own food in the forest. But the villagers’ animals don’t go out in winter. They’re afraid of the cold and anyway they’re so stupid that they might get lost in the forest and the villagers would never find them again. They don’t know Snakish, so they can’t summon living beings to them. That’s why they keep their animals all winter penned in and feed them with the hay they’ve gone to great trouble to collect in the summer. You see that’s why the villagers need that ridiculous rake, but we get by very well without it.”

“But what about the spinning wheel!” The wheel had left a more powerful impression on me than the rake. All those skeins and wheels and other whirring fiddly bits were to my mind so magnificent that it wasn’t possible to describe it in words.

Uncle smiled.

“Children like toys like that,” he said. “But we don’t need a spinning wheel either, because an animal skin is a hundred times warmer and more comfortable than woven cloth. The villagers simply can’t get hold of animal skins, because they don’t remember Snakish anymore, and all the lynxes and wolves run off into the bushes away from them, or, otherwise, attack them and eat them up.”

“Then they had a cross, and on it was a human figure, and Johannes the village elder said it was a god whose name is Jesus Christ,” I said. Uncle had to understand for once just what inspiring things there were in the village!

Uncle Vootele just shrugged.

“One person believes in sprites and visits the sacred grove, and another believes in Jesus and goes to the church. It’s just a matter of fashion. There’s no use in getting involved with just one god; they’re more like brooches or pearls, just for decoration. For hanging around your neck, or for playing with.”

I was offended at my uncle, for flinging mud at all my marvels like that, so I didn’t start talking about the bread shovel. Uncle would certainly have said something foul about it—something about us not eating bread anyway. I kept quiet, glowering at him.

Uncle smirked.

“Don’t get angry. I do understand that when you see for the first time how the villagers live all that flapdoodle turns a kid’s head. Not only a kid—a grown-up too. Look how many of them have moved from the forest to the village. Including your own father—he used to talk about how fine and nice it was to live in the village, his eyes glowing like a wildcat’s. The village drives you crazy, because they have so many peculiar gadgets there. But you’ve got to understand that all these things have been dreamed up for only one reason: they’ve forgotten the Snakish words.”

“I don’t understand Snakish either,” I faltered.

“No, you don’t, but you’re going to start learning it. You’re a big enough boy now. And it’s not easy, and that’s why many people today can’t be bothered with it, and they’d rather invent all sorts of scythes and rakes. That’s a lot easier. When your head isn’t working, your muscles do. But you’re going to start on it. That’s what I think. I’ll teach you myself.”

Four

n the old days, they say, it was quite natural for a child to learn the Snakish words. In those days there must have been more skilled masters, and even some who didn’t get all the hidden subtleties of the language—but even they got by in everyday life. All people knew Snakish, which was taught in days of yore to our ancestors by ancient Snakish kings.

By the time I was born, everything had changed. Older people were still using some Snakish, but there were few really wise ones among them—and then the younger generation no longer took the trouble to learn the difficult language at all. Snakish words are not simple; the human ear can hardly catch all those hairline differences that distinguish one hiss from another, giving an entirely different meaning to what you say. Likewise, human language is impossibly clumsy and inflexible, and all the hisses sound quite alike at first. You have to start learning the Snakish words with the kind of practice you take with a language. You have to train the muscles from day to day, to make your tongue as nimble and clever as a snake’s. At first it’s pretty annoying, and so it’s no wonder that many forest people found the effort too much, and preferred to move to the village, where it was much more interesting and you didn’t need Snakish.

Moreover, there weren’t any real teachers left. The retreat from Snakish had started several generations ago, and even our parents were only able to use the commonest and simplest of all the Snakish words, such as the word that calls a deer or an elk to you so you can slit his throat, or the word to calm a raging wolf, as well as the usual chitchat, about the weather and things like that, that you might have with a passing adder. Stronger words hadn’t come in for much use for a long time, because to hiss the strongest words—to get any result out of them—would need several thousand men at once, and there hadn’t been that many in the forest for ages. And so many Snakish words had fallen into desuetude, and recently no one had bothered to learn even the simplest ones, because as I say they didn’t stick in your mind easily—and why go to the trouble, when you could get behind a plow and work your muscles?

So I was in quite an extraordinary situation, as Uncle Vootele knew all the Snakish words—no doubt the only person in the forest who did. Only from him could I learn all the subtleties of this language. And Uncle Vootele was a merciless teacher. My otherwise so kindly uncle suddenly became very gruff when it came to a lesson in Snakish. “You simply have to learn them!” he declared curtly, and forced me over and over again to repeat the most complex hisses, so that by the evening my tongue ached as if someone had been twisting it all day. When Mother came with a haunch of venison, my head shook in fear. Just the thought that my poor tongue had to chew and swallow, in addition to all the twistings of the day, filled my mouth with a horrible pain. Mother was in despair, and asked Uncle Vootele not to exhaust me so much and to start by teaching me just the simplest hisses, but Uncle Vootele wouldn’t agree.

“No, Linda,” he told my mother. “I’ll teach Leemet the Snakish words so well that he won’t know anymore whether he’s a human or a snake. Only I speak this language as well as our people have from the dawn of time, and one day, when I die, Leemet will be the one who won’t let the Snakish words fade into oblivion. Maybe he’ll manage to train up his own successor, like his own son, and so this language won’t die out.”

“Oh, you’re as stubborn and cruel as our father!” sighed Mother, and made a chamomile compress for my injured tongue.

“Was Granddad cruel, then?” I mumbled, with the compress between my teeth.

“Terribly cruel,” replied Mother. “Of course, not to us—he loved us. At least I think so—but many years have passed since he died, and I was only a little girl then.”

“So why did he die?” I persisted. I had never heard anything about my grandfather before, and only now I came to the surprising conclusion that quite naturally my father and mother couldn’t have just fallen out of the sky; they must have had parents. But why had they never talked about them?

“The iron men killed him,” said Mother. And Uncle Vootele added, “They drowned him. They chopped his legs off and threw him in the sea.”

“What about my other grandfather?” I demanded. “I must have had two grandfathers!”

“The iron men killed him too,” said Uncle Vootele. It was in a big battle, which happened long before you were born. Our men went out bravely to fight with the iron men, but they were smashed to smithereens. Their swords were too short and their spears too weak. But of course that shouldn’t have mattered, because our people’s weapons have never been swords and spears, but the Frog of the North. If we’d managed to wake the Frog of the North, he would have swallowed up the iron men at a stroke. But there were too few of us; many of our people had gone to live in the village and didn’t come to our aid when they were asked. And even if they had come, they wouldn’t have been of help, because they no longer remembered the Snakish words, and the Frog of the North only rises up when thousands call on him. So there was nothing left for our men but to try to fight against the iron men with their own weapons, but that has always been a hopeless task. Foreign things never bring anyone good fortune. The men were cut down and the women, including your grandmothers, brought up their children and died of melancholy.”

“Our father, of course, wasn’t killed in battle,” Mother corrected him. “No one would dare go near him, because he had poison teeth.”

“What do you mean, poison teeth?”

“Like an adder’s,” explained Uncle Vootele. “Our ancient forefathers all had fangs, but as time passed and they forgot Snakish, their poisonous fangs disappeared. In the last hundred years very few of them have had them, and now I don’t know anybody who has them, but our father did, and he bit his enemies without mercy. The iron men were terribly afraid of him and fled for their lives when Father flashed his fangs at them.”

“So how was he captured?”

“They brought a stone-throwing machine,” sighed Mother. “And started firing rocks at him. Finally they got him and stunned him. Then the iron men tied him up, with whoops of joy, cut off his legs, and threw him into the sea.”