Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

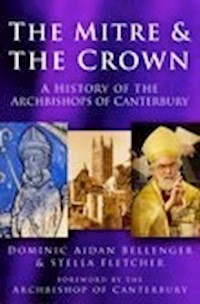

From St Augustine in the sixth century to Rowan Williams in the twenty-first, the archbishops of Canterbury have provided leadership for the English Church. Those called to the office have included saints and scholars, men of faith and men of action. More than a hundred archbishops of Canterbury have offered spiritual leadership and political influence, whether in co-operation with the secular power or as its critics. Royal dynasties have come and gone, but the succession of the Canterbury primates has provided a remarkably continuous thread running through the history of England. The Mitre and the Crown draws upon a wealth of recent scholarly literature to relate the story of the archbishops against a backdrop of more than fourteen centuries of English ecclesiastical history. It examines the social and cultural experiences that shaped the holders of the archiepiscopal office, together with the personal talents they brought to the service of both Church and State.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE MITRE & THE CROWN

THE MITRE & THE CROWN

A HISTORY OF THE ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY

DOMINIC AIDAN BELLENGER & STELLA FLETCHER

First published in 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Dominic Aidan Bellenger and Stella Fletcher, 2005, 2013

The right of Dominic Aidan Bellenger and Stella Fletcher to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9495 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Foreword by His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury

Acknowledgements

Archbishops of Canterbury and archbishops-elect

Introduction

1 597–1070: Conversion and Consolidation

2 1070–1270: Ecclesia Anglicana Reformata

3 1270–1486: From Mendicants to Princes

4 1486–1660: Canterbury between Rome and Geneva

5 1660–1848: Ecclesia Anglicana Instaurata

6 1848–2005: Gain and Loss

Appendix 1: English and Welsh dioceses held by prelates who became or who had been archbishops of Canterbury

Appendix 2: Tombs and memorials

Notes

Bibliography

FOREWORD

One of the most distinguished Anglican scholars of the twentieth century, Dom Gregory Dix, wrote some sixty years ago of the way in which the bishop’s office in England had varied over the centuries – from the ‘tribal wizard’ of Anglo-Saxon days to the gentleman-politician of the eighteenth century and the reforming headmaster of the Victorian age. He had no great opinion of the bishops of his own era, it must be said. But his perception is an acute one: the reality of episcopal ministry may be pretty continuous, but its embodiments have been wildly diverse. And what goes for bishops in general is emphatically true for the primates of all England.

The modern incumbent has to balance the urgencies of mission and witness in England with the increasingly complex needs of a worldwide network – as well as still struggling to maintain the heart of the work as a pastor to the parishes of east Kent. But the study of the office’s history, so comprehensively and elegantly set out in these pages, is a good defence against nostalgia for past glories. There may be an unregenerate flicker of mourning for the long-lost days when the job was regarded by at least some governments as an appropriate semi-retirement for prelates of failing strength and faculties. But being at the centre of British politics has always been a somewhat risky enterprise, and no contemporary primate is likely to feel much regret that his chances of a violent end at the hands of monarchs or rebels or invaders are a bit reduced.

Yet that history of involvement with the institutions of this society leaves its mark – not only on the office but on the society. England cannot be understood historically without understanding how and why the Church contributed to its very identity – while at the same time returning constantly to the vexed theme of how that Church defined itself as something more than a chaplaincy to the governing elite. The history of the archbishops is not only one of involvement with the nation’s institutions but one of argument and critical engagement – from Becket to Sancroft to William Temple’s extraordinary role in creating something of the consensus on which postwar welfarism could grow.

This admirable book does what any good piece of church history should: it concentrates our minds upon the strange mixture of solidarity and distance that always characterises the Church’s relation with the specific social worlds in which it finds itself. The questions that arise from trying to understand that mixture are among the most theologically serious that there are. This is therefore a deeply worthwhile study, and I hope that it will do its job in stimulating those deeper questions – as well as fascinating and instructing its readers.

Rowan Cantuar

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

When James Whistler was obliged under cross-examination to defend the asking price of 200 guineas for his Nocturne in Black and Gold: the Falling Rocket, a work ‘knocked off’ in a couple of days, he maintained that the figure was asked ‘for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime’. In a similar fashion, our first collaboration, Princes of the Church: a History of the English Cardinals (2001), was ‘knocked off’ quite briskly, but built upon the knowledge of two lifetimes. Research was little more than an exercise in filling in the gaps. Our readers proved to be far kinder to the book than Ruskin was to Whistler and the Falling Rocket, and their generous response duly resulted in the notion that we might like to produce a comparable volume about the archbishops of Canterbury. This time, though, the gaps in our knowledge were much wider, both chronologically and geographically. We were, for instance, more familiar with the churches and palaces of Rome than with those of Kent or Surrey. For the present book, therefore, we have found it necessary to seek advice and information, and are pleased to acknowledge the assistance so readily and cheerfully given by Cressida Annesley (Canterbury Cathedral Archives), Alexandra Berington, Brenda Bolton, Joy Cooper (at Abergwili), John Crook, Alan Crosby, Claire Cross, Alan Foster (at Farnworth), Anne and George Holmes, Doreen Holyoak (at Higham Ferrers), Jeanne and Bruce Males (at Addington), John McManners, Denise Mead (at Croydon), Angela Moore (Flintshire Record Office), Edward Norman, Daniel Rees, Jonathan Riley-Smith, Michael Riordan (St John’s College, Oxford), Deborah Saunders (Centre for Kentish Studies) and Richard Sharp. More mundane but no less valuable help has been provided by Sue Corke, Charles Fitzgerald-Lombard, Brenda and Frank Fletcher, Carolyn and Steve Gordon, Marjory Holt and Melissa Mahon. Particular thanks must go to Clare Brown, assistant archivist at Lambeth Palace, for guiding us so skilfully through the resources of Lambeth Palace Library and for introducing us to Archbishop Laud’s tortoise. The scale of the present work means that we have inevitably skimmed surfaces, most particularly with regard to those archbishops who doubled up as cardinals and have been treated at greater length in Princes of the Church. We hope that the result is sufficient to remind readers of the rich traditions embodied by the archbishop of Canterbury as heir to the monk Dunstan, the reformer Lanfranc, the theologian Anselm, and the martyr Becket, as well as to more recent defenders of ecclesiastical liberties against lay encroachment, episcopacy against Dissent, and Christianity itself against secularism. We are delighted that the weight of so much tradition has not prevented Archbishop Rowan Williams from contributing the foreword to this book.

Stella FletcherDominic Aidan Bellenger

ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY AND ARCHBISHOPS-ELECT

In most cases the first date refers to the year of consecration or enthronement, rather than that of election. Archbishops-elect appear in italics. Adapted from P. Collinson, N. Ramsay and M. Sparks, A History of Canterbury Cathedral, Oxford, 1995, pp. 563–4.

Augustine

597–604x9

Laurence

604x9–619

Mellitus

619–624

Justus

624x31–653

Honorius

627x31–653

Deusdedit

655–664

Wigheard

666/7–668

Theodore

668–690

Berhtwald

692–731

Tatwine

731–734

Nothhelm

735–739

Cuthbert

740–760

Bregowine

761–764

Jænberht

765–792

Æthelheard

792–805

Wulfred

805–832

?Feologild

832

Ceolnoth

833–870

Æthelred

870–888

Plegmund

890–923

Athelm

923x5–926

Wulfhelm

926–941

Oda

941–958

Ælfsige

958–959

Byrhthelm

959

Dunstan

959–988

Æthelgar

988–990

Sigeric

990–994

Ælfric

995–1005

Ælfheah (Alphege)

1006–1012

Lyfing

1013–1020

Æthelnoth

1020–1038

Eadsige

1038–1050

Robert of Jumièges

1051–1052

Stigand

1052–1070

Lanfranc

1070–1089

Anselm

1093–1109

Ralph d’Escures

1114–1122

William of Corbeil

1123–1136

Theobald

1139–1161

Thomas Becket

1162–1170

Richard of Dover

1174–1184

Baldwin

1185–1190

Reginald FitzJocelin

1191

Hubert Walter

1193–1205

Reginald

1205–1206

John de Gray

1205–1206

Stephen Langton

1207–1228

Walter de Eynesham

1228–1229

Richard le Grant (Wethershed)

1229–1231

Ralph Neville

1231

John of Sittingbourne

1232

John Blund

1232

Edmund Rich (Edmund of Abingdon)

1234–1240

Boniface of Savoy

1245–1270

Adam Chillenden

1270–1272

Robert Kilwardby

1273–1278

Robert Burnell

1278

John Pecham

1279–1292

Robert Winchelsey

1294–1313

Thomas Cobham

1313

Walter Reynolds

1313–1327

Simon Mepham

1328–1333

John Stratford

1333–1348

John Offord

1348–1349

Thomas Bradwardine

1349

Simon Islip

1349–1366

Simon Langham

1366–1368

William Whittlesey

1368–1374

Simon Sudbury

1375–1381

William Courtenay

1381–1396

Thomas Arundel

1396–1397

Roger Walden

1397–1399

Thomas Arundel (restored)

1399–1414

Henry Chichele

1414–1443

John Stafford

1443–1452

John Kemp

1452–1454

Thomas Bourchier

1454–1486

John Morton

1486–1500

Thomas Langton

1501

Henry Deane

1501–1503

William Warham

1503–1532

Thomas Cranmer

1533–1553

Reginald Pole

1556–1558

Matthew Parker

1559–1575

Edmund Grindal

1576–1583

John Whitgift

1583–1604

Richard Bancroft

1604–1610

George Abbot

1611–1633

William Laud

1633–1645

William Juxon

1660–1663

Gilbert Sheldon

1663–1677

William Sancroft

1678–1690

John Tillotson

1691–1694

Thomas Tenison

1695–1715

William Wake

1716–1737

John Potter

1737–1747

Thomas Herring

1747–1757

Matthew Hutton

1757–1758

Thomas Secker

1758–1768

Frederick Cornwallis

1768–1783

John Moore

1783–1805

Charles Manners Sutton

1805–1828

William Howley

1828–1848

John Bird Sumner

1848–1862

Charles Thomas Longley

1862–1868

Archibald Campbell Tait

1868–1882

Edward White Benson

1883–1896

Frederick Temple

1896–1902

Randall Thomas Davidson

1903–1928

Cosmo Gordon Lang

1928–1942

William Temple

1942–1944

Geoffrey Fisher

1945–1961

Michael Ramsey

1961–1974

Donald Coggan

1974–1980

Robert Runcie

1980–1991

George Carey

1991–2002

Rowan Williams

2002–

INTRODUCTION

They have been reviled and ridiculed, suspended and sequestered, impeached and imprisoned, deprived and degraded, exiled and excommunicated. They have met violent deaths by order of the Crown and of Parliament, and at the hands of revolting peasants, opportunistic knights and drunken Danes. Only the drunken Danes were not even nominally Christians. Apart from the more gory episodes, many archbishops of Canterbury have suffered daily martyrdoms in their witness to the Christian faith, and yet their office has survived – with a break in the mid-seventeenth century – for over 1,400 years. The archbishopric is older than the English nation, let alone the monarchy, and has endured the vicissitudes of both ecclesiastical and secular history. It has survived military and ideological invasions, and revolutions in Church and State. Royal dynasties have come and gone, but the archbishops of Canterbury have been there to crown monarchs, both before and since the creation of the Established Church. Survival was only possible with adaptation to changing circumstances. When status was determined by wealth and ownership of land, the archbishops were important landowners in south-east England, with a string of manors across Kent and Surrey; but when that socio-economic phase passed, they relinquished their estates and received instead a clerical stipend set at a suitably lordly rate. Britain’s ancien régime came to an orderly conclusion, but the archbishops of Canterbury nevertheless retained their position within the ruling elite. The nature of their jurisdiction – or jurisdictions – has evolved over the centuries and can be charted in the rise and fall of diocesan, provincial and legatine courts. To select just three examples, the Court of Arches1 survives from the thirteenth century, the Court of Audience disappeared in the seventeenth, and the court of High Commission was created in the aftermath of the sixteenth-century break with Rome, but abolished by the Long Parliament in 1640-1.2 The geographical area under the archbishop’s jurisdiction has also been subject to change: at diocesan level this can be illustrated by the temporary addition of Calais to the Canterbury diocese between 1375 and 1558; at provincial level it can be traced in the threat posed by the short-lived province of Lichfield in the eighth century, and also through the suppression and creation of dioceses on numerous occasions.

The earliest holders of the see of Canterbury were appointed by the pope and travelled to Rome to receive confirmation of that appointment in person. As a symbol of his metropolitan status – exercising authority over the various dioceses of which his province was composed3 – the archbishop received a pallium from the pope. This circular band of white wool, embroidered with black silk crosses, is worn over liturgical vestments and has pendants hanging to the front and back. In the Anglo-Saxon world, in particular, the pallium was charged with great power. The authority of the pope lay in the bones of Peter, a power extended to the bishop through the pallium. It is placed on or near St Peter’s tomb before being conferred, thus bringing the touch of Peter himself and becoming a relic of the apostle. When archbishops of Canterbury ceased to visit the papal court in person, the pallium was sent to them in England. That practice ceased in the sixteenth century, though the symbolic value of the pallium was retained in the Anglican archbishops’ coats-of-arms. In pre-Reformation Canterbury the monks of Christ Church formed the cathedral chapter and claimed the right to elect the archbishop, who was their nominal abbot; the bishops of the province of Canterbury also claimed the same right. In practice the monks were bound by the wishes of the king, and were not free to elect anyone until they had obtained from him a congé d’élire (‘permission to elect’). Freedom of episcopal election from lay involvement was at the head of Magna Carta in 1215, but the assertion of this right had little impact on royal intervention, which itself came into conflict with the pope’s claim to provide bishops to vacant sees and not merely confirm capitular elections. The appointment of Archbishop Simon Mepham illustrates the complexity and the length of the process: on 11 December 1327 he was elected by the Canterbury chapter; royal assent was signified on 2 January 1328; papal confirmation followed on 25 May and consecration by Pope John XXII at Avignon on 5 June; the temporalities (estates) of the see were ‘restored’ to him on 19 June; he was finally enthroned at Canterbury on 22 January 1329. From the death of Archbishop Walter Reynolds on 16 November 1327 the entire process had taken nearly fourteen months.

When, from the sixteenth century onwards, reference was no longer made to Rome the appointment procedure was considerably shortened. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it fell to the prime minister to select the bishops of the Church of England.4 Any number of swift appointments could be cited, but that of John Bird Sumner may be taken as typical: Archbishop William Howley died on 11 February 1848; Lord John Russell selected Sumner, the bishop of Chester, and his appointment was officially confirmed at St Mary-le-Bow on 10 March. Sumner’s enthronement at Canterbury followed on 28 April, just eleven weeks after Howley’s death. Since 1976 the powers of appointment have been vested in the Crown Appointments Commission and the dynamics of patronage have been replaced by those of bureaucracy. The Vacancy-in-See Commission appoints the four-member Crown Appointments Commission, which shortlists candidates and forwards two names to the prime minister who, in turn, commends one name to the monarch. Only then do the dean and chapter of Canterbury – heirs to the monks of Christ Church – elect the name with which they have been provided. From the announcement in January 2002 of Archbishop George Carey’s intention to resign to the enthronement of Archbishop Rowan Williams on 27 February 2003 was a period of over thirteen months: closer to fourteenth- than to nineteenth-century practice.

Although St Augustine of Canterbury enjoyed metropolitan status, received the pallium from Pope Gregory the Great and created suffragan bishops of London and Rochester, the first holder of the see of Canterbury to be styled ‘archbishop’ was Theodore of Tarsus, nearly a century after Augustine’s arrival in Kent in 597. Theodore’s successor Berhtwald was the first archbishop of Canterbury to be specifically designated ‘primate’, which literally means ‘holder of the first see’ (prima sedes).5 A primate holds authority not only over the bishops of his own province but also over several provinces and metropolitans, rather like exarchs in the Eastern Church. Primates exist by privilege rather than by right. This ecclesiastical oneupmanship, which acknowledged the archbishop of Lyon as primate of the Gauls, and those of Esztergom and Toledo as primates of Hungary and Spain respectively, has largely dwindled into a matter of historic interest in the Roman Catholic world, leaving concern with the position and powers of primates to the Church of England and the Anglican Communion. As metropolitans of the northern province, the archbishops of York were also primates, and disputes about precedence became a recurring feature of English church history. One particularly virulent outbreak occurred in the twelfth century between William of Corbeil and Archbishop Thurstan of York, in consequence of which the accord of Winchester (1127) made the subtle distinction between the archbishop of York as ‘primate of England’ and Canterbury as ‘primate of all England’. In 1874 there was talk of Archbishop Tait achieving a higher status yet. When the second Lambeth Conference visited Canterbury he addressed the assembled bishops from the throne of St Augustine, the marble chair, and appeared to some as orbis Britannici Pontifex or even as Papa alterius orbis, a true pope of empire.6 At the beginning of the twenty-first century, in relation to the question of authority that besets the Church of England and the Anglican Communion, The Times can still ask, ‘Do Anglicans need a pope?’

One archbishop who rather thought they did was Edward White Benson in the late nineteenth century. However circumscribed his ecclesiastical powers in reality, Benson could be in no doubt of his social standing, as Debrett’s Peerage assured him that he was

the first peer of England next to the Royal Family, preceding not only all Dukes, but all the great officers of the Crown. The Bishop of London is his provincial Dean, the Bishop of Lincoln his Chancellor and the Bishop of Rochester his Chaplain. ‘It belongs to him to crown the King’, and the Sovereign and his or her Consort, wherever they may be located, are speciales domestici parochiani Arch. Cant. (parishioners of the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury). The Archbishop is entitled to the prefix of ‘Your Grace’ and styles himself ‘By Divine Providence Lord Archbishop of Canterbury’.8

To this admirably clear statement of his position, it may be added that the archbishop is formally addressed as ‘The Most Reverend and Right Honourable the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury’, a combination that recognises both his clerical status and his position as a peer of the realm. He signs himself ‘Cantuar’, a shortened form of the Latin for ‘Canterbury’.

The primate of all England presides over a Church wedded to the State and exercises a primacy of honour among the leaders of the worldwide Anglican Communion, but he still traces his ecclesiastical ancestry back to St Augustine, the missionary monk sent to bring the English people into the Roman Church at the end of the sixth century. No archbishop was more conscious of this than Matthew Parker, the man appointed in 1559 to put the Elizabethan Settlement into practice. While more zealous reformers sought to sever all connections with anything that smacked of ‘popery’, Parker emphasised the importance of continuity between the pre- and post-Reformation English Church, and did so through the compilation of a history of the archbishops of Canterbury: De antiquitate Britannicae ecclesiae et privilegiis ecclesiae Cantuariensis cum archiepiscopus eiusdem (1572). It is a work of antiquarian scholarship typical of its time and can serve as an English parallel to the lives of popes and cardinals compiled by Girolamo Garimberti and Alfonso Chacón in the same period.9 Parker followed the story through from St Augustine to his own immediate predecessor, Reginald Pole, and carefully enumerated a total of sixty-nine archbishops. His list does not include Ælfsige and Byrhthelm in the tenth century or Roger Walden in the fourteenth, all of whom are counted in the official Church of England list that makes Rowan Williams the 104th holder of the office.10 At the same time, Parker does recognise the archbishops-elect Reginald FitzJocelin and John Offord, in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries respectively. These discrepancies almost cancel out one another: if Parker’s list is brought up to date, there have been 103 archbishops of Canterbury in total, rather than 104. On the other hand, the number rises to as many as 117 if all the archbishops-elect are included in the calculation; it declines to a maximum of eighty-three for anyone who refuses to recognise Anglican Orders.

Historiographically, Parker’s successor was Walter Farquhar Hook, a long-serving vicar of Leeds in the mid-nineteenth century, who took violently against what he regarded as the ‘Romish’ practices of E.B. Pusey in the neighbouring parish of St Saviour. From 1859 Hook was dean of Chichester and his twelve-volume Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury (1860-76) began to appear the following year. It is a monumental work, with much attention devoted to somewhat surprising details. Hook was a self-confessed enemy of ‘Romanism’, an admission that must be borne in mind when reading his heavily laboured account. Considerably more accessible is A.E. McKilliam’s one-volume history of the archbishops up to Randall Davidson, A Chronicle of the Archbishops of Canterbury (1913), replete as it is with anecdotes and biographical details. Edward Carpenter’s Cantuar: the Archbishops in their Office first appeared in 1971 and has been through three editions, the most recent (1997) with a new introduction and lively additional chapter by Adrian Hastings. Carpenter was a ‘modern churchman’, dean of Westminster from 1974 to 1985, and the biographer of Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher; Hastings was on the liberal wing of Roman Catholicism. Cantuar is heavily weighted towards the Anglican period in the history of the archbishops, which gives the present authors scope to appreciate the pre- and post-Reformation periods as parts of a unified whole. When Carpenter produced his first edition, the Church of England was still bolstered by all the certainties of Establishment. Establishment remains, but in just a generation or so the ‘certainties’ have effectively disappeared, providing a considerably more challenging environment in which the archbishop of Canterbury endeavours to preach the Christian message of love and forgiveness, hope and reconciliation.

With over a hundred principal players and an extensive supporting cast of popes and monarchs, bishops and nobles, statesmen, families and friends, the present volume cannot provide more than a fairly impressionistic account of each archbishop and his career. Its format does, however, permit the tracing of four intertwined strands through fourteen centuries. The strongest of these, binding together all six chapters, is that provided by the relationship between Church and State, a relationship that began with Augustine’s mission to King Æthelberht of Kent in 597. As a single English kingdom evolved, so the primacy of Canterbury became a reality, confirmed by the archbishop’s part in the coronation rite. The post-Conquest period, from the time of Lanfranc in the eleventh century to that of Boniface of Savoy in the thirteenth, witnessed the full spectrum of Church-Crown relations. These ranged from Lanfranc’s restructuring of the English Church and close co-operation with the Conqueror through to the violent conclusion of Henry II’s feud with Thomas Becket. In the period covered by the third chapter, competing papal and royal claims to appoint candidates to vacant benefices were interspersed with bouts of conflict between pope and king over clerical taxation. With the Avignon popes enjoying the support of England’s French enemies and the post-Avignon papacy seriously weakened by schism, many of the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century archbishops of Canterbury found it expedient to distance themselves from Rome and become loyal servants of the Crown. Simon Sudbury and Henry Chichele provide prime examples of this policy. Chapter four takes the Canterbury saga from Cardinal Morton in the late fifteenth century to William Laud in the seventeenth; in so doing it seeks to emphasise continuity in the service of the archbishops to the Tudor and early Stuart monarchs, whether or not those monarchs acknowledged papal supremacy. The emergence of the Church of England as the ecclesiastical arm of the State redefined the archbishop’s position, so that he became that pillar of the Establishment described in Debrett. During the Anglican centuries there have been differences of opinion over individual pieces of legislation and unimaginative newspaper headlines about ‘turbulent priests’ speaking out against particular government policies. However, since the restoration of episcopacy in 1660, the most serious breach between the primate and either the Crown or Parliament was as long ago as the deprivation of Archbishop Sancroft in 1690. Royal coats-of-arms displayed prominently in churches continue to provide ample visual evidence of the Church of England’s Established status, but of greater relevance in the present context are the pairs of churchwardens’ staffs of office found in Anglican parish churches, topped as they are by miniature mitres and crowns.

As references to papal authority indicate, the history of even so English an institution as the Canterbury archbishopric cannot easily be told in isolation from the wider world. Stifling insularity is avoided in the present account by weaving in the second of our four strands, that of the archbishops’ international role, whether in the context of pre-Reformation Christendom, post-Reformation imperialism, or in the world of scholarship unconstrained by national boundaries. Scholarship brings us to the third strand, that of literary and material remains: the archbishops as writers, collectors of books, builders and restorers of churches and palaces, and occupants of tombs. In each of these capacities, their contributions must necessarily be accounted for in only the briefest of terms, but their publications and building projects can at least serve as convenient indices of their vision of the Church and understanding of their mission.

The fourth strand deals with the ‘anatomy of leadership’ and accounts for the experience that individuals brought to the office of archbishop in terms of their geographical and social background, their education and the networks of contacts they acquired prior to holding senior office. For the pre-Conquest period this is more or less confined to a tentative exploration of the monastic world to which so many of the archbishops belonged, even before becoming abbots of Christ Church. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, monastic networks gradually gave way to university ones, based on the Oxford-Paris axis. Oxford remained the intellectual home of the fourteenth-and fifteenth-century primates, among whom there developed a marked consciousness of whether or not they were born into England’s ruling elite. The early modern period witnessed the eclipse of the Oxford canon lawyers, the rise to episcopal prominence of Cambridge theologians and then the return of Oxonians with heightened theological awareness, a sequence otherwise known as the English Reformation. Among the post-Restoration archbishops, from Juxon to Howley, university-based networks remained significant, but episcopal careers were in large measure determined by the patronage of the aristocratic elite. Dynasticism of the ecclesiastical variety comes to the fore in the history of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century archbishops of Canterbury, the privileged world of the Taits, Davidsons, Bensons and Temples only gradually giving way to the more suburban milieu of Runcie, Carey and Williams. Archbishop Williams makes headlines as do few other church leaders today, and this presents a useful opportunity to explore and reflect on the careers of his predecessors, the princes and the statesmen, the exiles and the martyrs.

1

597-1070: CONVERSION AND CONSOLIDATION

Anglo-Saxon England was steadily transformed by the consolidation of its new Christian identity. Opportunities for artistic and technical expression provided by the Church furnished an exquisite series of works of art and maintained a spiritual integrity which defied the Viking raiders and illuminated what was never really such a ‘dark’ age. At an historical and cultural level, arguably the greatest innovation introduced by Christianity was the art of reading and writing, essential for the dissemination of the Word, and resulting in the production of those written records from which the past may be partially reconstructed. The story these records tell is of an increasingly unified people in which the ecclesiastical structure of metropolitan and bishop gradually encompassed and redrew the frontiers of the highly competitive English kingdoms. The Christian Church created a new national identity and, beyond that, an awakening to an inheritance of faith associated with the Roman Empire and an enticing world of cities and civilisation. The establishment of the see of Canterbury was central to bringing the English people, who lived towards the edge of the known world, into close, creative and lasting relations with the other provinces of Christendom. The Channel was not so much a barrier between England and continental Europe as a means of access to ports which, like all roads, ultimately led to Rome.

Christianity had made its mark in Britain since at least the third century, as can be seen in remaining fragments which incorporate such characteristically Christian images as the chi-rho symbol. A Kentish example of this early Christian art can be found in the wall paintings of the Roman villa at Lullingstone near Eynsford. In addition to the archaeological evidence, written records provide tantalising hints at an original diocesan structure from which a delegation of British bishops, those of York, London and Caerleon-on-Usk, was sent to the Council of Arles in 314, an assembly called by the first Christian emperor, Constantine (d. 337), to counter the Donatist heresy. A century later, in 410, the imperial authorities abdicated responsibility for Britain’s defences, leading to the settlement of southern and eastern parts of the island by Angles, Saxons and Jutes from what is now Denmark and northern Germany. Christianity may well have become practically invisible in south-east Britain, but further west the native authorities stabilised their position in the late fifth century and remained in close contact with the Mediterranean world until the middle of the following century. The Celtic Church, for all its cultural singularity, remained thoroughly Roman in creed and origin; it was less an independent phenomenon and more that branch of the Universal Church which happened to exist in Celtic-speaking Britain. Irish monasticism, ascetic and wandering, flourished in the sixth century and, shortly before Augustine’s arrival in England, the Hibernian monk Columbanus began his series of great continental monastic foundations, including Luxeuil (590), near Vesoul, and Bobbio (612), some 40 miles inland from Genoa. Among the correspondents of Columbanus was Pope Gregory the Great (590-604).1

Pope Gregory is remembered as the apostle of the English and the founder of the archbishopric at Canterbury. Bede celebrated him thus:

We can and should by rights call him our apostle, for though he held the most important see in the world and was head of churches which had long been converted to the true faith, yet he made our nation, till then enslaved to idols, into a church of Christ, so that we can use the Apostle’s words about him: ‘If he is not yet an apostle to others, yet at least he is one to us, for we are the seal of his apostleship in the Lord’.2

In the wider Church his name became renowned as the last of the four Latin Doctors, joining Ambrose (d. 397), Jerome (d. 420) and Augustine of Hippo (d. 430) as interpreters of the faith. Gregory was born into an aristocratic Roman family with two recent popes as kin. Following a classical education he served for some years (c. 572–4) in the important civic office of praefectus urbi, prefect of the city, before rejecting worldly wealth and embracing the monastic life, transforming his residence on Rome’s Caelian Hill into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Andrew. The city of Rome was in long-term decline, caused in no small measure by Constantine fixing his capital at Byzantium – Constantinople – in 330. By Gregory’s time imperial rule in Italy was mediated through the exarch of Ravenna, leaving the popes to rule Rome by default. In 579 Gregory was sent to Constantinople by Pope Pelagius II (579–90) as part of a united effort between Rome and Constantinople to counter the encroachment of German Lombard power in Italy. He stayed there until 585 and met Leander of Seville (c. 550–600), whose conversations inspired Gregory’s great book of biblical scholarship, the Moralia, a commentary on the book of Job. He returned to Rome as secretary to Pope Pelagius and, on his patron’s death in 590, was himself elected to the papal office. However great his worldly success and skill in human affairs, Gregory’s aspirations remained focused on personal sanctification and citizenship of the heavenly Jerusalem. He was convinced that the day of judgement was close at hand and that, as supreme pontiff, he had an urgent obligation to preach the Gospel to the ends of the world. His surviving writings, which include some 850 letters as well as the Liber regulae pastoralis (Book of Pastoral Care, c. 591), written for all those who exercise the cure of souls, are replete with pastoral sensitivity and an awareness of the urgency of the task. It is within this context that the mission to the English makes most sense.

Gregory’s first biographer, a monk of Whitby who wrote about a century after the pope’s death, was the first to record the story about Gregory encountering the English boys in the Roman slave market. The ‘Non Angli, sed angeli’ anecdote is also recorded by Bede. Both authors place the incident long before Gregory became pope, suggesting a long gestation for his English mission plan. In 596 he sent a party of forty missionaries from Rome to the court of King Æthelberht of Kent (d. 616x18), where the queen, Bertha, was a great-granddaughter of Clovis (d. 511), the first Christian king of the Franks. As Clovis had been in part converted by his Burgundian wife Clotilde (d. 545), so Bertha and her Frankish chaplain, Bishop Liudhard (d. c. 603), were harbingers of Christianity in Kent. Thus ‘an English king who wanted to become a Christian and a pope with an overwhelming desire to save the world’ became linked through ‘the Frankish royal court, provider of information and later, through the bishops, of practical help’ for the nascent English Church.3

Gregory’s chosen instrument was Augustine, a Roman monk who was serving in 596 as prior of Gregory’s monastery in Rome. Little is known about his background or personality other than Gregory’s commendation of his knowledge of Scripture in a letter of 601 to Æthelberht and the evidence of some understandable faintheartedness in responding to Gregory’s invitation to embark on such an ambitious mission. As Bede relates, Augustine landed in Thanet, that portion of north-east Kent separated from the rest by the River Stour (or ‘Wantsum’, as Bede names it), and sought out Æthelberht, whose capital was at Canterbury, formerly the Roman town of Durovernum Cantiacorum. Canterbury had been deserted in the fifth century, but began to function again as an urban centre in the sixth and seventh centuries. When Augustine arrived its most conspicuous building was the Roman theatre, an eminently suitable tribal meeting-place. Æthelberht’s Kentish kingdom was enjoying a temporary pre-eminence in Britain for, in spite of being one of the smaller tribal realms, Æthelberht exercised some measure of overlordship over the other kingdoms south of the Humber. Kent also enjoyed a gateway status, exploiting the trade routes that ran to London from the French and Frisian ports. In the encounter between Augustine and the Kentish king, the conversion of Æthelberht himself was crucial: ‘if the conversion of the king could be secured, then that of his nobility and their retainers was virtually assured’.4 This objective had been achieved by 601, in which year Gregory dispatched a supplementary group of missionaries led by Abbot Mellitus and including Paulinus, the future bishop of York.

Augustine’s success in converting Æthelberht did not help him in his attempt to come to terms with the existing Christian priests and people in Britain. The missionary’s agenda contained efforts to restore a lost province to the Roman Church and to build in England a new Rome. Gregory flattered Æthelberht in his letters, casting him as a new Constantine and Bertha as a new Helena. Canterbury, barbaric and dilapidated, slowly came back to life, transforming itself (in Bede’s rather overstated phrase) ‘into the metropolis of [Æthelberht’s] empire’. Royal power and influence duly ensured that Christianity gradually permeated northwards from Canterbury with new bishoprics at Rochester and London (from 604) forming the nucleus of an expanding Church. Mellitus was the first bishop of London and another Roman missionary, Justus, that of Rochester. Gregory the Great planned his English Church with twin metropolitan centres at London and York, cities which had gained distinction as centres of Roman civic government and military organisation respectively, and which remained strategically important. There were to be twelve bishoprics in each of the two provinces. Augustine himself failed even to reach London and the patronage of Æthelberht ensured that Canterbury duly became England’s ecclesiastical centre.

The Anglo-Saxon centuries are represented in Canterbury’s archaeological record by a deep layer of dark earth. While Roman stone structures, not least the city walls, survived, the wooden buildings of the Anglo-Saxon period have not. The street pattern, on the other hand, is almost entirely Anglo-Saxon, the Roman gridiron having been rejected. Within the walls, in the north-east quarter of the city, Æthelberht provided an existing church for Augustine’s use. This became Augustine’s cathedral, served by monks and dedicated to the Holy Saviour, Our Lord and God, Jesus Christ. Its dedication as Christ Church has survived throughout its entire history. As adapted by Augustine, it is thought to have been a building of simple design, consisting of a nave and apsidal sanctuary.5 Close to Christ Church but outside the city wall, lay the land donated by Æthelberht for a second monastic foundation, dedicated to Sts Peter and Paul, the patrons of Rome, reminding us of the pleasure Bede expressed when he noted how closely Canterbury’s customs accorded with those of Rome. This second foundation later became St Augustine’s Abbey, named in honour of its founder, and was designed to act as a mausoleum for both kings and archbishops. Royal mausolea provided architectural opportunities for dynastic display and, in the case of Christian monarchs, for clear affirmations of their commitment to Christianity. The burial church endowed by Clovis outside the walls of Paris was a case in point. Reflecting the dual significance of Christ Church as locus of the archiepiscopal cathedra and St Augustine’s as the burial place of canonised archbishops, the hagiographer Goscelin of Saint-Bertin (d. after 1107) stated ‘there he rules, here he dwells’. St Augustine’s, thoroughly ruined at the Dissolution, has been excavated to reveal the various levels of its building from the seventh century onwards. The first burial places of the kings and early archbishops are visible and marked. The new shrine area, where Augustine and his successors were translated in 1091, has entirely disappeared. Within a century of the twin foundations, though, the seeds were sown of centuries-long discord between the archbishop, who was effectively abbot of Christ Church, and the community at St Augustine’s, for a papal privilege granted by Pope Agatho (678–81) gave the monks of St Augustine’s exemption from all but papal authority and the freedom to elect their own abbot. At the time it seemed like an honour for a singularly successful monastery, but the long-term consequence was to create a monastery exempt from the archbishop’s jurisdiction just yards from his own cathedral.

Augustine’s English career was relatively brief, for he died between 604 and 609, but it established the themes which can be traced through the lives of his successors up to the Norman Conquest. At the most fundamental level, the archbishops’ position was firmly tied to the fluctuating fortunes of the English kings and kingdoms. External forces were highly varied, ranging from the devastation caused by Viking raiders to the considerably more benign influence of the distant popes, without whose confirmation an archbishop-elect could not exercise authority. Even in Augustine’s lifetime, the foundations of an English episcopal framework were laid; the evolution of that episcopal system can be traced through the careers of his successors. At its heart lay the city of Canterbury and its two great monastic houses, with both of which the archbishops remained intimately connected. Like Augustine, many of the archbishops were themselves monks and their careers cast important light on the nature of English monastic history. First, though, something must be said about the relatively limited number of written sources through which each of these threads can be traced.

The first nine holders of the see of Canterbury – from Augustine to the election of Tatwine – together with its first unconfirmed and unconsecrated archbishop-elect, Wigheard, were memorialised by Bede the Venerable. The archbishops’ modern historian is inevitably struck by the contrast between the thoroughness of Bede’s coverage of the 130 years or so after the arrival of Augustine in Canterbury and the relative paucity of information about the archbishops who lived during the following two centuries. It is only post-Bede that serious doubts arise about the identities of the archbishops and their personal histories. Bede was an early member of the Wearmouth monastery founded in 674 by Benedict Biscop and subsequently, from 682, a founder member of Biscop’s house at Jarrow. While his mental world was seemingly boundless, his relatively limited physical travels took him only as far as York. Biscop, by contrast, was an inveterate traveller, visiting Rome five times, and it was his library that made possible Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (completed 731). For Canterbury material he owed most to Albinus, abbot of Sts Peter and Paul (St Augustine’s), his ‘principal authority and helper, a man of universal learning’ (like Bede himself) who collated the Canterbury sources and was very helpful on Roman documentation. Although Bede’s narrative provides much of our information about the English Church of his time, his native Northumbria inevitably emerges in sharper focus. Similarly, although Gregory the Great in distant Rome is presented as the hero of the second book of the Ecclesiastical History, Robert Markus reminds us that Bede’s writings, with their strong emphasis on wonders and miracle stories, display ‘an emblematic picture of the tensions between the continental model of the Christian Church, organised on a territorial basis with bishops in charge of dioceses, and a British model, monastic and charismatic in its emphasis.’6

The miraculous was indeed central to the history of the early archbishops of Canterbury, all of whom attracted cults based on their tombs. It was only with the confused conditions of the ninth century that these localised cults grew more obscure and that it became an option for an archbishop not to be recognised as a saint. In the centuries after Bede, the tradition of writing saints’ lives, and even of setting them in their historical context, was not quite lost, but the disappearance of libraries and the secularisation of property which followed the Viking raids made it a tenuous line of literary descent. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the single most important source for the history of England in that period, provides some chronological framework, but it was not until the eleventh century that the archbishops of Canterbury received more detailed biographical attention. The Latin lives of the monastic reformers like Dunstan, whose life was recorded by ‘B’ and Adalhard, were supplemented by a group of writers who breathed new life into the great men of Canterbury. Goscelin began his monastic life in the Benedictine house of Saint-Bertin at Saint-Omer, but travelled in southern and central England from 1058 and settled at St Augustine’s, Canterbury, from 1090. Goscelin was a skilled hagiographer and a passionate defender of Canterbury’s authority over York, which had had its own archbishop since 735. Osbern (d. c. 1072) produced accessible lives of Archbishops Ælfheah (Alphege) and Dunstan. Although most directly associated with the epoch-making life of his contemporary Anselm, Eadmer (d. c. 1128) also wrote widely on the English saints. William of Malmesbury (d. c. 1143) was the author of important histories of the English nation and the English Church, and neglected no opportunity to discuss the native saints or to further their cults.

Augustine’s four immediate successors were not only buried in what became St Augustine’s and honoured as saints; they were all Italian monks who arrived in England in the missionary waves of 597 and 601. Laurence had been sent back to Rome as Augustine’s intermediary, but returned to England in time to be named by Augustine as his successor. Bede passes sketchily over the pontificate of Laurence until the death of King Æthelberht in 616 or 618 and the succession of the pagan Eadbald. An anti-Christian reaction overwhelmed the fledgling Church. Bishops Mellitus of London and Justus of Rochester fled into exile and Laurence was on the verge of following their example when he saw himself in a dream being flogged by St Peter for his cowardice and resolved to stay in Kent. According to Bede, the crisis soon passed and Eadbald converted to Christianity. The miraculous looms no less large in the Northumbrian’s coverage of the five-year pontificate of Mellitus, who came to the primacy with missionary experience among the East Saxons of his London diocese and diplomatic experience as Laurence’s envoy to Rome. Bede prefers to concentrate on the story of how a devastating fire spread through the city of Canterbury and raged close to the church of the Four Crowned Martyrs. Mellitus was old and infirm but requested his attendants to carry him to this place, where he prayed that the city might be delivered from the flames. The wind thereupon changed direction and the conflagration was quelled. Justus (d. 627), the fourth archbishop of Canterbury, had been bishop of Rochester since 604, so clearly ranked next to Mellitus in seniority. Although the date has been disputed, the consecration of their missionary colleague Paulinus as bishop of York has traditionally been placed in 625, making it likely that Justus was his consecrator and therefore the episcopal godfather of the Northumbrian Church. When Justus died in 627, Paulinus was left as the only bishop in the whole of England. It therefore fell to him to consecrate Honorius (d. 653), another of Gregory’s Roman monks, as the fifth archbishop of Canterbury.

Bede’s attention was understandably distracted from Canterbury by the baptism of King Edwin (d. 633) of Northumbria at Easter 627, a somewhat delayed consequence of his marriage with the Christian princess Æthelberga of Kent (d. 675). Northumbria had become a single kingdom with the coalition of the rivals Deira (between the Humber and the Tees) and Bernicia (between the Tees and the Firth of Forth). It reached the peak of its power in the middle of the seventh century under Edwin and his nephew Oswy (d. 670). The only power they could not vanquish was that of Mercia, under the leadership of King Penda (d. 655). Although Bede insists that Penda was not overtly hostile towards Christianity, which was accepted by his son Paeda as a condition of marriage with a Northumbrian princess, it was only after Penda’s death that the Mercians embraced the Christian faith. While Northumbria experienced a monastic and cultural golden age in the seventh and eighth centuries, epitomised by the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 696–8), Mercia was militarily ascendant. By c. 800 the Mercian kingdom controlled not only the whole of central England as far as Offa’s Dyke to the west and a line between the Mersey and the Humber to the north, but also the former kingdoms of the East Angles, East Saxons, South Saxons and Kent. The death of Æthelred II in 762 and the short reign of Eadberht II marked the effective end of the Kentish ruling dynasty and the Mercian king Offa (d. 796) was in control of the former kingdom by 765. Mercian supremacy was short-lived and Kent was annexed by the next ascendant kingdom, Wessex, in c. 825. The archbishops of Canterbury worked with whichever power happened to be dominant in the region: they were all Christian. The Norwegian Vikings, on the other hand, did not accept Christianity until the tenth century and began raiding towns and monasteries along the British coast from 793 onwards. The Danes were still largely pagan until the later ninth century and were predominant in raids on the coastline of eastern England. Canterbury was sacked in c. 851. Northumbria, East Anglia and a large part of Mercia fell to the Scandinavian invaders. By 876 York had become the capital of a Danish kingdom, covering most of Deira, while Bernicia remained in native hands with Bamburgh as its capital. The West Saxons, led by Alfred the Great from 871 until his death in 899, put up tougher resistance, preventing the complete conquest of the island and laying the foundations for the united kingdom of the English. The defeat of Erik Bloodaxe in 954 marked the expulsion of the invaders from Deira, Lindsey and East Anglia, though Viking raids and widespread disorder resumed later in the century. Edgar of Mercia and Northumbria became the first king of a united English kingdom in 959. For a while, tenth-century Canterbury ceased to be vulnerable to attack and benefited from the relative stability of Anglo-Saxon government, while the archbishops could concentrate on their pastoral commitments. The Danes returned and duly invaded most of England, Cnut the Great (d. 1035) incorporating it into his short-lived empire around the shores of the North Sea. This time, the invaders were fellow Christians, just as they were in 1066, after the reign of the English king Edward the Confessor.

When the ecclesiastical map of southern Britain is superimposed on that of the fluctuating native kingdoms and the waves of invaders and settlers from overseas, the role of the archbishops of Canterbury naturally appears to be more prominent. In the seventh century it was Honorius who sent the Burgundian missionary Felix (d. 647) to convert the East Angles and become their bishop. His see was fixed on the coast at Dunwich, which remained a bishopric until the late ninth century. Honorius was less involved in the evangelisation of the West Saxons, which was entrusted to Birinus by Pope Honorius I (625–38). In 634 Birinus established his cathedra at Dorchester-on-Thames, near Oxford, but Wessex soon acquired bishops at Winchester (from 660) and Sherborne (c. 705), and Dorchester fell under Mercian rule. In 644 Archbishop Honorius made English ecclesiastical history by consecrating Ithamar as bishop of Rochester, the first native Englishman to attain episcopal status. The first English archbishop of Canterbury was Honorius’s immediate successor, a West Saxon called Frithowine or Frithona, who took the name Deusdedit and was consecrated by Ithamar on 12 March 655. The events of Deusdedit’s pontificate are largely obscured by the prominence accorded by Bede to the Synod of Whitby, summoned by King Oswy of Northumbria in 664 to iron out the discrepancies between the Celtic practices emanating from Ireland and Iona, on the one hand, and those of Rome, which reached his realm via Canterbury and York, on the other. The ‘Roman’ delegation was led by Bishop Agilbert of Wessex and Abbot Wilfrid (d. 709) of Ripon, rather than a direct representative of Canterbury, but it nevertheless persuaded Oswy to choose Roman practices, most notably the dating of Easter, over those of the marginalised Celtic Church.7 Wilfrid’s reward was the bishopric of York, his consecration taking place in Frankish territory and by Frankish bishops because he considered the Celtic bishops to be in schism.

Deusdedit died soon after the synod, but a potential successor could not be found for some time. The chosen candidate was Wigheard, a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury. Bede relates that the kings of Northumbria and Kent jointly decided to send Wigheard to Rome to receive consecration from the pope, though the delay and the Roman mission also suggest that Wigheard’s position among his fellow bishops may not have been too secure. Wigheard died in Rome and Pope Vitalian (657–72) selected his replacement. The pope’s first choice was Hadrian the African, an abbot in Italy and a scholar celebrated for his knowledge of monastic and church discipline. Hadrian rejected the offer but recommended instead Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek monk of relatively advanced years. It was 669 before Theodore reached England, where he found the Church in need of effective leadership, not least because plague had removed a number of bishops. Never before had Canterbury experienced so protracted a vacancy. Although aged sixty-five at the time of his appointment, Theodore proved to be an energetic and farsighted prelate, whose activities are known to us from Bede. He began with a thorough visitation designed to sort out anomalies. By 672 a sufficient degree of order had been restored for Theodore to call and preside over the first general synod of the English Church. As if to underline the geographical inconvenience of Canterbury for anything but access to the coast, this was held at Hertford on 24 September 672 or 673. This was not only the first all-English ecclesiastical council; it was the first all-English assembly of any kind. Theodore’s main task was to secure geographically fixed sees for the English tribal kingdoms, whose borders fluctuated under political pressure. It was agreed that bishops should not intervene in the affairs of other dioceses and an order of precedence among bishops, based on practice found elsewhere in the Church, was established. York was not yet a separate province, so Theodore was perfectly able to interfere in its affairs, dividing it into three dioceses and incurring the ire of Bishop Wilfrid, who went to Rome to appeal to the pope. To ensure the continuity of synodical practice, provision was made for further councils to be held at an intriguingly unidentifiable place called Clovesho (or Clofesho), somewhere in the Mercian sphere of influence. Another council certainly met at Hatfield in 679, but that was concerned with doctrinal matters and declared its rejection of the short-lived Monothelite heresy. Theodore has sometimes been credited with too much – the creation of the parish system as we now know it, for example – but his quest for unification of the disparate elements of the English Church was so successful that Bede was able to conclude that ‘the English churches made more spiritual progress during his archbishopric than ever before’.