11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

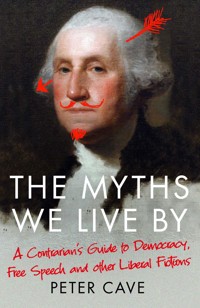

In this witty and mischievous book, philosopher Peter Cave dissects the most controversial disputes today and uses philosophical argument to reveal that many issues are less straightforward than we'd like to believe. Leaving no sacred cow standing, Cave uses ingenious stories and examples to challenge our most strongly held assumptions. Is democracy inherently a good thing? What is the basis of so-called human rights? Is discrimination always bad? Are we morally obliged to accept refugees? In an age of identity politics and so-called 'fake news', this book is an essential resource for reinvigorating genuine public debate - and an entertaining challenge to accepted wisdom.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

THE MYTHS WE LIVE BY

‘Lively… Cave forces his readers to interrogate cherished beliefs and see how many of the principles enshrined in public life are not only inconsistent but incoherent, even paradoxical.’

The Herald

‘At its best, The Myths We Live By resembles a lively tutorial, with the genial Professor Cave challenging readers’ prejudices… Useful and educational.’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘An elegant and erudite exposé of the hypocrisies and evasions that infect the social and political thinking of our times.’

John Cottingham,Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, Reading University

‘Britain’s wittiest philosopher.’

Raymond Tallis, bestselling author ofThe Kingdom of Infinite Space

PETER CAVE lectures in philosophy for New York University (London) and the Open University. He is the author of numerous articles – some academic and serious, others humorous – and several philosophy books, including the bestseller Can a Robot Be Human? He has scripted and presented philosophy programmes for BBC Radio 4 and often appears in the media, taking part in public debates on matters of ethics, religion and politics.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2020

Copyright © Peter Cave, 2019

The moral right of Peter Cave to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 522 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 521 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

DEDICATED TO

those many victims of liberal and democratic myths – including those victims who think they are no victims at all

CONTENTS

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Prologue: On hiding what we know

1 What’s so good about democracy?

2 How democracy lies

3 Freedom and discrimination: burqas, bikinis and Anonymous

4 Should we want what we want?

5 Lives and luck: can Miss Fortuna be tamed?

6 The Land of Justice

7 Plucking the goose: what’s so bad about taxation?

8 ‘This land is our land’

9 Community identity: nationalism and cosmopolitanism

10 What’s so good about equal representation?

11 Human duties – oops – human rights

12 Free speech: the Tower of Babel; the Serpent of Silence

13 Regrets, apologies and past abuses

14 ‘Because I’m a woman’: trans identities

15 Happy Land

Epilogue: In denial

Notes and References

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Most people would rather die than think – and that is what they do.

Bertrand Russell

This book is not for the fainthearted; well, it is not for those who prefer to be untroubled by thinking, whether or not that preference outweighs their preference for life. It is not for the fainthearted because it asks readers – all of us, be we left, right, centre or nowhere – to reflect on our societies’ realities and ideals. It urges us all to open our minds instead of tricking ourselves with self-deceiving comforts, easy platitudes or by simply ‘looking away’. The thinking mind needs more than sighs of ‘never mind’.

Think of Covid-19. Suppose the virus ravaged only the poorest in the world; suppose it left untouched earnings of major corporations; suppose it caused minimal disruption to those reasonably well off and did not hamper the travels and luxury consumptions of the wealthy. Would there be so much concern for controlling it? Would there be urgent searches for vaccinations and treatments? Suppositions to one side, contrast the vast resources deployed to provide numerous luxuries for those who can afford them with the fewer resources devoted to the provision of clean water and basic health care to the world’s poorest. Ideals of human dignity – and also of liberty, rights and democracy – are easily distorted by the huge discrepancies in wealth and power.

Since this book was first published, the tricking and distortions of our lived reality – and of our gleaming ideals – are all the more in evidence. Here are two arenas of trickery recently in expansion. They relate to governments in both the United States and the United Kingdom and hence relate to the political ‘right’. Were governments of different persuasions in power, other troubling examples would probably be on offer.

First, consider democracy. In the UK, as a result of the 2019 general election, Boris Johnson’s Conservative premiership was refreshed with a large majority. That electoral success occurred despite numerous well-attested examples of Johnson not speaking the truth. Those examples were, earlier on, highlighted by many Conservative politicians as demonstrating him unfit to be prime minister, yet many of those politicians subsequently provided him with unquestioning support. Memory loss has advantages – self-serving, political advantages.

In that 2019 election period, there were the usual unjust distortions caused by the UK’s first-past-the-post voting system as well as those resulting from some people being unable to register to vote, some registered voters being deterred from voting, and the distribution of misinformation to various targeted groups. ‘Fake news’ was supplemented by the fakery of what we may now term ‘no news’. As well as refusing to release an independent report on any Russian involvement in UK politics, Johnson avoided various hard-hitting interviews, preferring instead to answer robust questions such as, ‘And what shampoo do you use, Prime Minister?’

The ‘no news’ agenda continues with government ministers declining invitations to take part in certain flagship political interviews. ‘No one was available for comment from the government’ has become an oft-repeated mantra. In some cases, because the government has refused to put up ministers, broadcasters, in the name of balance, have withdrawn invitations to the opposition’s shadow ministers. Thus, the trumpeting of democratic governments being ‘held to account’ is increasingly mythical, increasingly illusory.

Secondly, consider international law and human rights. The United States’ Republican President Trump, early in January 2020, ordered a drone strike to bring about the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani when visiting Iraq. The strike also killed nine people around him; their deaths, ‘collateral damage’, were quickly forgotten. Soleimani was head of Iran’s elite Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force; he was responsible for some terrorist acts, much suffering and many murders. There was, though, no evidence of his posing an immediate threat to the United States or its allies. The killing – most legal experts accept – contravened international law, was itself a terrorist act and maybe a war crime. It also generated an Iranian response, leading to jittery Iranian forces mistakenly shooting down a civilian airline; nearly two hundred innocent passengers were killed. Thus it is that outrages lead to outrages.

Drawing attention to that international violation by the United States is not to defend the Iranian regime. Neither within nor outside that regime does it receive any serious acclaim as a shining example of liberalism and democracy. Contrast with the United States: the US is ever keen to polish itself with liberal and democratic credentials, seeing itself as a fine respecter of international law. Few believe that Trump’s keenness for the assassination had nothing to do with his running for re-election in 2020 and his need to appear strong on US security. Trump’s ‘killing success’ may remind us of Osama bin Laden’s assassination being used by the Democrat President Obama to help his 2012 re-election. Some may recall how a certain Donald Trump of 2012 objected to Obama basking in his ‘killing success’; as Trump insisted, the Navy SEALs, not Obama, killed bin Laden.

In late 2018, Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered – a gruesome murder – while in Saudi’s Istanbul consulate. The United States and European democracies expressed outrage. Later, in 2019, the United Nations Special Rapporteur concluded that Khashoggi was the victim of an extrajudicial killing for which the Saudi Arabian state was responsible; there was credible evidence that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and other high-level officials were individually liable. Unsurprisingly, our liberal democracies have allowed the matter to slide into the dusty pages of last year’s news reports. Memory loss, once again, is politically convenient.

There are many instances of how respect for international law by liberal democracies is somewhat mythical. In March 2020, the High Court in London found that Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Dubai’s ruler – horse-racing friend of Queen Elizabeth II – kidnapped his two grown-up daughters, Sheikha Latifa Al Maktoum and Sheikha Shamsa Al Maktoum. Shamsa has not been seen for over a decade. At the time of Shamsa’s kidnapping – she was grabbed when in Cambridge, nearly twenty years ago – the British governmental authorities apparently ensured that further police investigations did not take place. It is not an outrageously unjustified prediction that, after a while, British relations with Dubai and the Sheikh will be as close as ever, despite the High Court judgement.

Of course, all is not well in countries that are miles away from what we in Western liberal democracies would deem liberal and democratic. Most notable examples are the ways of the Chinese authorities. Reflect on their initial response when Dr Li Wenliang of Wuhan Hospital alerted medical colleagues, in December 2019, to the dangers of Covid-19. Had Dr Li not been silenced and the authorities acted more swiftly, it is just possible that the virus would not have spread worldwide, causing considerable disruption and so many deaths, including Dr Li’s. Putting matters in perspective, though, the number of deaths and predicted deaths from the virus may be very small compared with those that occur annually through poverty.

Of course – again – we could reflect on many other examples of dubieties in our liberal democracies and not just those relating to the UK and America. Other democracies, from Australia to Israel to France, have political corruptions that tarnish their democratic credentials or undermine their commitments to human rights.

Returning to the UK, not so long ago there were investigations into links between individuals suffering cuts in welfare benefits and subsequent suicides. Curiously, some of those reports were destroyed by the government, citing data protection legislation, despite data protection authorities denying that such destruction was required. In 2020, there were court hearings concerning Julian Assange’s WikiLeaks, with the United States demanding Assange’s extradition. During those hearings, it became increasingly apparent that Assange had been mistreated both while imprisoned and while in court. In 2019, independent United Nations human rights experts expressed concerns over his treatment, yet the UK, apparently, shrugged them off.

Political debate, in some arenas, is under greater pressure. In both the UK and the US, criticism of Israeli policies towards the Palestinians is often rewarded by accusations of ‘antisemitism’. When the criticisms are by Jewish groups, the groups tend to be disparaged as ‘fringe’ and dismissed. In both the UK and the US, the term ‘transphobic’ is rather readily showered upon people who doubt whether, for example, biological males can rightly be women, grounded solely in self-certification, and receiving all the rights of biological women. As well as obvious dangers of ‘tyranny by the majority’, liberal democracies face dangers of tyranny by certain minorities.

Political debate is increasingly devalued. When Prime Minister Johnson and President Trump make claims that are manifestly untrue, they seem to be accepted by many – including the Prime Minister and President – as par for the course and to be laughed off. ‘Who cares? So what?’ mark their attitudes. That does not bode well for democracy and the importance of people’s participation.

The above are examples of how, in practice, respect for democracy, for human rights, free speech and liberty are under attack. Witness in the UK how the feeling is being created that the BBC, public broadcaster much praised worldwide over the decades, must be commercialized or more or less abandoned. Witness the increases in ‘no-platforming’ of those who would challenge certain currently preferred views on gender, race or cases of ‘historical abuse’.

The arguments in this book take us much further, though – into realizing that we are not even clear over what constitutes the ideals of democracy, human rights, liberty and so forth. We know, vaguely, the rightful direction for those ideals but lack a reliable compass and lack awareness of how far to go. We need to think, question and debate, considerably more than we do – instead of carelessly shrugging our shoulders, with sighs of ‘never mind’ as leaders smile and bluster while deploying ‘fake news’ or ‘no news’. That is why I opened this preface with Bertrand Russell’s wry despair at how many people resist thinking – a despair that Russell was not the first to express.

Russell (1872–1970) was an eminent philosopher, logician and political activist; he argued for social reform, sexual liberation and was active in peace protests, the latter leading to his being sent to prison – three times. The first imprisonment was his reward for protesting during the First World War against conscription. With Russell’s aristocratic connections – he was 3rd Earl Russell, his grandfather having been prime minister, Lord John Russell – the then Home Secretary authorized his transfer to prison hospital with the provision of pen and paper, so he could continue writing his Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy. He secured that privilege via advantages of class; such privileges these days are more often grounded in wealth, silver tongues of barristers – or defendants’ practice in use of walking frames.

Let me use Russell’s life to highlight three important lessons. First, we should not dismiss what people say because they are poor or lacking in formal education; and we should not dismiss what people say because they are aristocratic, wealthy or ‘experts’. We should look at the reasoning and values expressed – whether the values are, for example, of self-interested greed or compassion for others.

Further – and here is the second lesson – Russell’s public protests as president of the CND (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), later of the Committee of 100, should remind us that, contrary to declarations by those in power, extra-parliamentary protests – Russell and others sitting in London’s Trafalgar Square, refusing to move – are not undemocratic. They are sometimes the only way in which injustices and dangers can receive recognition. In 1851, Lord Campbell proclaimed in Britain’s House of Lords, ‘There is an estate in the realm more powerful than either your Lordship or the other House of Parliament – and that is the country solicitors.’ Global corporations, ‘the market’ and market manipulators – yes, assisted by embedded legal structures for property ownership – form today’s most powerful estate.

Let us remember today’s most powerful estate, if inclined to mockery or condemnation of organizations such as Extinction Rebellion or of leaders such as Greta Thunberg when they are engaged in protests. Of course, that does not mean that we ought always to be uncritical of such movements; the movements and their leaders may at times come over as possessed of a religious ‘greener than thou’ fervour, viewing mention of any values other than green as the work of sinners who need to be shown the light.

A third lesson from Russell’s life is that he changed his mind. John Maynard Keynes famously said, ‘When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, Sir?’ Russell certainly changed his mind. Both Keynes and Russell, I am sure, would recognize that we may rightly change our minds, even when the facts have not changed.

Thinking, reflecting, musing, may lead us to look at matters afresh, becoming aware of previous prejudices or false assumptions. In this work’s prologue, I tell of farmyard geese arguing over which sauce will go best with them once they are cooked and ready to be eaten. With no change in the facts, the geese may one day come to see how they could be discussing a far more fundamental matter – how to flee their unfortunate fate. This book, I hope, will at least encourage us to delve into the realities and ideals of our liberal democracies and possibly even help us to flee some of the many distortions, inconsistencies and deceptions by which we live.

Allow me to add an observation from Ludwig Wittgenstein to those by Russell and Keynes. When at Cambridge, all three were much involved with each other’s thoughts in the ‘moral sciences’ that then covered moral philosophy, logic and political economy. Wittgenstein recommended that when two philosophers meet, they should say to each other, ‘Take your time.’

This book is meant for those who prefer to think than to die. It is meant for those who are prepared to change their minds. This book – a book on certain topics within the ‘moral sciences’ – requires that, in thinking about these matters, we ‘take our time’.

PROLOGUE

On hiding what we know

Perseus wore a magic cap that the monsters he hunted down might not see him. We draw the magic cap down over eyes and ears as a make-believe that there are no monsters.

Karl Marx

This is a book about political and public hypocrisy or, more generously, political and public myths. These myths are espoused by many politicians, judges, captains of industry, commentators, religious leaders – the great and the good – and, more generally, by much of the population of our liberal democracies. They are myths by which they and we live. They are myths embraced by many with an unquestioning and unbridled enthusiasm.

Picture the following farm. The geese are arguing imaginatively, and with gravitas, over which sauce will go best with them once they are cooked and ready to be eaten. We may easily agree that they could be discussing a far more fundamental matter – how to flee their unfortunate fate – but that discussion is not on the agenda – well, not in this version of the tale. Perhaps they are so deceived that they fail even to grasp the possibility of escape. Perhaps a myth holds them captive, the myth that to be eaten is how things ought to be.

The myths of our liberal societies hold us captive; they also captivate. They relate to how things are, according to some; they also relate to how well things could be, according to others. The myths apply to certain ideals as much as to what is maintained to be the reality. They are metaphorical monsters – monstrous myths that need to be openly acknowledged, confronted, exposed, if there is to be any chance of slaying. Here are a few examples.

‘We are all equal before the law’ is a mantra much cloaked in praise, yet we know that its mouthing is of a myth. Some are, so to speak, more equal than others – namely, those who can afford the most talented attorneys, solicitors, barristers. That, of course, ignores a further injustice: namely, how many, many people cannot afford even to gain access to the law – to the courts; to justice. In 1215 King John of England issued the first Magna Carta, the Great Charter; it and subsequent versions are admired internationally as shining examples of first steps towards citizens’ rights. British politicians celebrate such rights, bask in their glory. Clauses 39 and 40 of the 1215 Charter, all those centuries ago, forbade the sale of justice and insisted upon due legal process – yet, week after week, practices of the British and American legal systems, government policies and wealth inequalities undermine the operation of such clauses, ensuring that the shining glory of rights is deeply tarnished.

Both the political left and political right extol aspiration, ambition and realizing talents; they are curiously quiet on how they rely on millions to be in employments that few deem aspirational: street cleaners, sewage workers, slaughterers in abattoirs – the list could go on. Talk of equal opportunities continues to be fashionable, yet the ideal is as mysterious as the reality is distant.

Liberty, freedom – here the terms are used interchangeably – is much lauded in liberal democracies. Singing its virtues, businesses, particularly with the political right in support, worship free markets, curiously forgetting that we need money to enter those markets. Millions of people lack the money; hence they lack the freedom. Free markets do not thereby make people free; on the contrary, they can be oppressive, luring people into wanting what they cannot have or getting what they would be better off without.

Governments promoting freedom conveniently forget the adage that freedom for the pike is death for the minnows. Freedom for the wealthy to own vast private estates has meant that millions of people have had their liberty to roam much curtailed. Unfettered freedom for property developers can fragment local communities, replacing them with towers of luxurious apartments, owned not as homes but as investments; some locals remain, their sky views blocked, their green spaces destroyed, while others are moved to distant parts, maybe trekking back daily to work. Of course, untrammelled freedom for certain minnows is not that great either because others find themselves terrorized by gangs – by small shoals – of the alienated, alienated from society through hopelessness and that mysterious nonsense of ‘equal opportunities for all’.

In many instances, related to those above, principal claims by our leading politicians, corporate executives, commentators et al. are manifestations of straightforward hypocrisy. They know what the truth is, yet they would have us believe otherwise. With a wave at a certain US president elected in 2016, they are, we may say, ‘trumpists’. Trumpism with regard to truth has been manifested for centuries. ‘Alternative facts’ are nothing new – save, maybe, for the trumpeting of them as, in some way, entertaining. It should not, though, be entertaining to hear governments’ proclamations of their respect for all human life, while promoting arms fairs and approving the export of rocket launchers and other military equipment and expertise to the Middle East with devastating consequences for millions of innocent civilians.

The intentions of politicians, intellectuals and others are, in some cases, noble; they deceive people as a stimulus, in the hope of achieving a better world. In 2010, to secure support for his Affordable Care Act (‘Obamacare’) that would help millions of Americans, United States President Barack Obama lied, saying that, under the Act, ‘If you like your health care plan, you will be able to keep your health care plan. Period.’ Obama was relying on public ignorance; his aim, in this instance, was the public good. Often, though, politicians deceive voters just to secure their own power. In Britain’s 2010 general election, the Conservative Party forcibly impressed on the electorate that the then Labour government was in some way responsible for the 2008 global financial crisis and for earlier ‘not fixing the roof when the sun was shining’. The party neglected to mention that it had supported Labour’s earlier spending plans, had furthermore called for greater financial deregulation and would no doubt also have had no option but to bail out the banks when the crisis hit.

The cases immediately mentioned are deceptions relating to particular events. The focus of this book is the set of deceptions, often self-deceptions, concerning the pervasive myths which ground our liberal democracies. Do we, for example, have any clear idea of what, ideally, a free society would be like? When our political leaders, our bishops, imams and rabbis, speak of all human life deserving respect and dignity, does that mean that we ought to forgo our numerous luxuries, diverting funds, for example, to ensure the provision of clean water in those inhabited areas where it is currently absent?

What I have written here is sometimes provocative; sometimes it is playful. Often behind the words there is a certain anger – contempt, indignation – towards many of our leaders for what they get away with, be they politically left or right, be they religious, atheist or in between, when piously mouthing their commitments to justice, equality and liberty. In challenging our liberal democracies, I am not implying support for those many, many states that manifestly are neither liberal nor democratic.

Of course, I am far from alone in urging that we face the truth and see the myths for what they are. My numerous letters in newspapers – from, so to speak, ‘Shocked of Soho’ – are little stingings, balloon puncturings, in the hope of waking people up, of opening eyes. Eyes, though, remain closed; we all, much of the time, sleepwalk even in our waking lives, manifesting varying depths of slumber.

This book is a sustained attempt at making us face our deceptions regarding cherished values of liberal democracies. Its heart is philosophical reasoning. Philosophical reasoning pushes concepts to their limits, taking arguments to their conclusions, not shying away from unwelcomed outcomes. The reasoning seeks out consistencies and inconsistencies in our actions and feelings, our ‘real-life’ transactions and what we declare to uphold as right. With the appeal to consistency and the exposure of inconsistencies – with incongruities between what we say that we value and what our actions show – the forthcoming chapters call us to challenge the silver tongues of our political, social and business leaders. The sentiments of this book could – indeed, should – lead some politicians, captains of industry, merchants of ideas and ideals, to feel at least a little guilty at their deceits and possibly own up. The sentiments, arguments and reflections may even encourage our leaders to go a little way towards making amends.

For some readers, this book may lead to the reflection, ‘Well, we knew that all along.’ Even to elicit such observations, if explicitly and reflectively acknowledged, may help people to seek to change things – for the better – though that better, as already noted, also guides us into a land of make-believe if we are not careful.

‘All things conspire,’ wrote Hippocrates of Kos, an ancient Greek philosopher. Lovers of ‘neo-liberalism’ glorify individual liberty; that typically goes hand in hand with the insistence that self-interest is people’s primary motivation, which leads to praise for the right to private ownership of capital – as much as people can get – and that takes us to the claim that the social order is best served through laissez-faire, through ‘free’ markets. Here, then, we shall see how ideas on liberty conspire with those of equality which lead into justice, then on to humanity, discriminations and solidarity, and back to liberty. Thus, diverse themes are woven throughout the chapters, appearing in one, then reappearing later in another, with new connections. The chapters and their contents may therefore have been arranged differently; there is no magic in reading from cover to cover rather than dipping within. By the way, in what follows, I use ‘United Kingdom’, ‘Britain’ and ‘Great Britain’ interchangeably, save where I note in Chapter 9 how the terms cover different nationalities.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are famously known for The Communist Manifesto, but it is Marx’s Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1867) that provides the heading of this Prologue. In their 1846 The German Ideology, they criticized philosophers for ignoring how things are:

In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven. That is to say, we do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men…

In contrast to Marx and Engels – though in their spirit – I examine what is said, to show how distant it is from reality, and also often from sense. I seek to remove the magic cap that covers both the reality and the ideal. I shed some darkness with the aim of shedding light.

1

What’s so good about democracy?

It seemed a great idea at the time. Being a democrat and liberal, I joined the Good Ship Democracy for a Mediterranean cruise. It possessed vast attractions for me, not least because my fellow passengers would, no doubt, be of my persuasion: all for democracy, for equal rights, for free speech.

Trouble started when the crew noticed that there were storms to the East and rocks to the West. ‘Which way should we steer – or should we turn back?’ they asked.

Foolish as I am, I assumed that the ship would deploy the services of a captain or pilot with expertise and knowledge of the Mediterranean seas, storms and safe harbours. The crew explained the error of my thinking. On the Good Ship Democracy, it transpired, we needed to vote on such matters, on all such matters.

‘But I have no idea which is the best way to go, which is the best way to vote,’ I complained, feeling a little irritated – and, yes, very worried. Other passengers joined in, agreeing that voting in this context was a silly and dangerous procedure. Others, though – the travelling know-it-alls – had no doubts, waving away our complaints. ‘We know what it is best to do,’ they insisted. It was a pity that those with such certainty disagreed with each other over what exactly that was. What exactly was the best thing to do?

The crew told us not to fret. Before we voted, we would be provided with charts, weather forecasts and instruction guides on how to assess those charts and forecasts. That struck us as making some sense: we could then evaluate the conditions and vote accordingly. That did indeed strike us as making good sense, until we realized that different sailors were providing us with conflicting data and very different readings of the data; in fact, much of the data seemed as baffling to the sailors as to us. Further, it soon became clear that some of us were pretty gullible or careless in reasoning; and some sailors were far more silver-tongued than others. The old hands wined and dined us, eager to persuade us of their expertise; others, it transpired, had personal reasons for what they advocated: some were wanting to turn back because missing the comforts of lovers left at home; others wanted to press on regardless, in expectation of adventurous romances to come.

The voyage continued in this way – or, rather zigzagging ways – as more decisions were required, more votes taken, with little consistency of approach manifested by our votes. How we envied other cruises that seemed to know exactly how to go and where to go.

Our Good Ship Democracy would still be meandering across the seas, save for the rocks that it struck. We abandoned ship, with some emergency helicopters coming to our rescue, manned by the military. Fortunately, we were not asked which way to fly to reach the shore.

The vignette above has at heart a fundamental criticism of democracy, as expressed by Socrates in Plato’s dialogue, Republic. The dialogue was written around 380 BC in ancient Athens, being the first substantial and enduringly influential text of political philosophy. Surely, we need experts – philosophers, indeed – to assess the best way for a society to run; Plato referred to those individuals as ‘Guardians’ of the ideal society, of the Republic. Even with the charts provided when on board Good Ship Democracy, few of us could have made sensible judgements. Even if the electorate is well-informed, there are many doubts about how competent most members are in assessing economic likelihoods, social justice and international relations – even in assessing their own best interests. In any case, if there is a right answer, why go through the ritual of voting and why take the risk of assuming that the majority vote reaches that answer?

‘Ah,’ it is replied to Plato, ‘no doubt we need experts for the means, explaining the different means to an end; but, in contrast to deliberating about means, we surely should all have a say in what sort of society we want, what we are aiming to achieve and what we are prepared to countenance to secure those aims. There is no “the” right answer for there is a plurality of ways of living.’

It is true that most of us cannot work out economic and social implications of a variety of different policies; experts, though, can often tell us what is likely to happen as a result of certain policies, the risks involved and how society would develop for the different groups within. We can then vote on the basis of which policies overall we prefer: that is where the democratic vote of the majority justifiably comes to the fore.

Plato would disagree. Plato’s approach would have not merely an expert captain, steering us clear of rocks and storms, but a captain who would also be expert in telling us what our destination should be, which destination is best for us – best, indeed, for one and all of us.

Surely, many continue to insist, Plato is wrong in his belief in the existence of an expertise in ends. It is up to us whether we should prefer to end up in Turkey, Israel or Egypt – and it is up to us what kind of society we want. Some people may prefer a society destined towards low taxation and few social-welfare benefits; others may prefer just the opposite. Some may prefer a society that promotes free thinking, alternative ways of living and religion; others may prefer conformity and tradition. Once experts have informed us of the different viable means to the various desired ends, then it should be for us to decide which to follow.

Our reply to Plato, as implied, is grounded in a ‘pluralism’; there are different ways of living, different ends, different priorities regarding the means. No expert can tell us which are the best. We have some diverse values, conflicting desires and a spectrum of attitudes to risk. As already indicated, some people prefer society to be liberal, where citizens’ conduct is relatively unconstrained; some prefer a more regimented society where we all ‘know our place’. Some may be easy-going over the availability of abortion, voluntary euthanasia and same-sex marriages; others, perhaps for religious reasons, would impose restrictive laws pertaining to such matters. Priorities also differ: some place health services provided by the State as of higher value than speedier rail connections. In Britain there is considerable scepticism by many about the billions of pounds to be spent on the HS2 rail project – a vanity project, as it is seen – billions that could be better spent on social care and housing.

The above observations can have light cast upon them by the philosophy of David Hume, the great Enlightenment Scot of the eighteenth century. Hume was a good-humoured man who would obliterate his philosophical melancholy and scepticism by dining, conversing with friends and playing backgammon. In his A Treatise of Human Nature (1738) he makes the point that preferences, passions – what we ultimately value – are not determined by reason:

’Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger. ’Tis not contrary to reason for me to chuse my total ruin, to prevent the least uneasiness of an Indian or person wholly unknown to me. ’Tis as little contrary to reason to prefer even my own acknowledge’d lesser good to my greater, and have a more ardent affection for the former than the latter…

Being human, we naturally have plenty of preferences in common – few choose their total ruin – but we do not all possess the same preferences regarding how society should run. No expertly reasoned answer is available about which ways of living are politically best justified; hence, a mechanism is needed to determine what politically should be done. That mechanism is the democratic vote.

Some individuals would no doubt prefer to follow their own agreed way of living; they can readily grasp how others also have preferences to have their own, but different, ways. Attempted resolution by physical battle would lead to chaos for all; leaving the field, becoming hermits, has few attractions. Democracy, by contrast, has a central attraction; it offers an approach where, it seems, we can all have a say in what to say, in how we are ruled. We all can vote; we can all agree to accept the outcome. It is as simple as that – except it is not simple and not as simple as that.

Most people today approve of democracies. Dictatorships seek the linguistic privilege of deeming themselves ‘democracies’ sometimes even in their formal names. We have, for example, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria. Such dictatorial democracies receive much mockery from the ‘true democracies’ of the West. To cast serious doubt on democracy in practice there is, in fact, no need to fly off to those dictatorships enmeshed in linguistic gymnastics. We could simply look at our own Western democracies, as we shall do in Chapter 2. In this chapter the attention is directed at the defects of democracy even as an ideal to be pursued – though, to expose certain defects, we shall inevitably encounter some clashes with the practice.

It is important to note: the reasoning above regarding how democracy is needed to handle conflicting preferences was not itself justified by democratic votes. Democratic voting may justify the policies governments pursue, but it cannot justify using democratic voting – for that would be circular, akin to lifting yourself, as is famously said, by your bootstraps. Democratic voting was justified above (be it well or poorly) by reasoning regarding what individuals should rationally accept as the best way to run a society. Plato would approve of the approach – that of rationality – but, as seen earlier, argues that there are faults in the reasoning in favour of democracy.

DEMOCRACY: FAILURE IN THEORY

A democracy, in essence, consists of some machinery: there is an input from ‘the people’, various wheels turn, levers clang, steam hisses – and the eventual outcome is a government. What the government does is meant to bear some relationship to the interests of the people whose votes were the inputs. What is the relationship? Surprisingly, there is vagueness at a most fundamental level.

When people vote – even the most reflective – they are unclear how they should be determining their votes. What does democracy theoretically require? Listen to voters. Some openly say that they are voting in what they consider to be their best interests – or their grandchildren’s best interests – or what is best for the planet. Others may be doing their best to vote on what is best for the society or best for people in general or for the poor – or to be in accord with certain religious beliefs. There is a mishmash of aims.

True, the machinery could be justified as a means of delivering a result when people’s interests and aims differ; and people should simply vote in their own (perceived) best interests. The machinery, though, could be justified as delivering a proper result only if voters vote on what they sincerely think is in the community’s best interests. In neither case, though, is the outcome satisfactory.

If people are voting in what they take to be their own interests, there is no reason at all to believe that the machinery (however it works) delivers something that is in fact in the interests of the community or even in the interests of the majority of voters. If people are voting in what they take to be the community’s interests, there is no reason to believe that the machinery delivers what is in fact in the community’s interests. People make mistakes both about what is in their own interests and about what is in the community’s. Unless we ascend to Platonic heavens, we are stuck here in the grubby real world of mistaken views, genuine bafflement and conflicting interests. After all, the interests of corporate executives do not typically coincide with the interests of those working on factory lines. True, all may, for example, have the same interest in reducing the number of murders, but democratic voting is no reliable means to achieve that desirable reduction. In Britain a majority often call for the reintroduction of capital punishment – but that majority view could be in the belief that capital punishment deters would-be murderers, a belief for which there is no convincing evidence.

Even if we accept that people should vote on policies on an ordered-preference basis – first choice is this; second choice is that; weigh accordingly – determined by their own interests, contradictions can arise, leaving it unclear how to determine the ‘right’ collective decision. An example is in this chapter’s endnotes. As the economist and Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen quipped, ‘While purity is an uncomplicated virtue for olive oil, sea air, and heroines of folk tales, it is not so for systems of collective choice.’

It is time to wheel on stage Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an eighteenth-century philosopher, born in Geneva, a major influence on the Enlightenment and indeed the French Revolution through his ideas in The Social Contract (1762). Here we meet his notion of the ‘General Will’ – the Will that advances the community’s interests and upholds the interests of all the citizens. Mysteriously, the General Will is constant, unalterable and pure; mysteriously, it can be discovered if people vote for what they believe is in the community’s interests. Now, it is certainly plausible that in a village, club or small enterprise, members may have a strong sense of community and will vote for what they honestly believe is best for the community – and get it right. That sense of community, though, may not be very strong when we have in view a vast nation, itself made up of very diverse groupings. Despite that, Rousseau proclaims the benefits of outcomes determined by majority votes. Here is how.

In a reasonably sized community – in fact, the larger the better – majority opinion, argues Rousseau, is more likely to be right on any matter than any individual voter. This may be laughed out of court, but it has a mathematical justification given by Nicolas de Condorcet, a liberal thinker of the eighteenth century, a thinker much exercised with problems of majority voting and collective decisions; he criticized the French revolutionary authorities and ending up dying in prison. His Jury Theorem shows the advantages of following majority votes, albeit on assumptions that are highly unlikely to hold in typical national elections. The assumptions are that all voters are cooperating to find a mutually beneficial answer to the same question and each has an equal and better-than-evens chance of getting it right – or even, in some versions of the theorem, that the average is better than evens. Then, over the long run – an important qualification – the majority is more likely to be right than any individual. Of course, we have no reason to think that each voter has a better-than-evens chance of getting things right, even if they are independently and sincerely voting for what they believe is in the national interest. Further, if they do not have the better-than-evens chance, then the mathematics shows that the majority outcome is more likely to be wrong.

An obvious practical case of a majority of those who voted getting matters wrong is the outcome of the 1933 election in Germany. Under the Weimar Republic, most people were having a bad time, but after voting in Adolph Hitler, leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (the Nazi Party), matters became substantially and radically worse – obviously for the Jews in Germany, but also for Germans more generally and, indeed, for millions of people outside of Germany.

There remains, of course, the fundamental challenge, namely whether there is anything that is the ‘getting it right’, the best for the community, for society. Perhaps it is elusive. If only we could reason better or heed the ways of Plato’s Guardians or even make sense of Rousseau’s mysterious General Will, our eyes would be opened to the glittering prize of ‘the best’. There is, though, no good reason to believe it exists. After all, why think there is only one way of ruling, of voting – of living – that is rightly understood as in the interests of the community? In addition, even if certain minimal requirements could be shown to ground what is best for the community as a whole, it does not follow that they provide what is best for each and every member of the community. The best for all is not necessarily the best for each one and all.

Without the best in view, perhaps the value of a democracy rests on the minimal fact that ‘everyone’ has the right to vote, to participate. There exists equality at least with regard to that right. I acquire the same rights over others as they do over me. Even if such equality is in the interests of the community and all its members, in practice in most democratic systems, the right to vote is much constrained by various registration requirements and irregularities; they are reviewed in Chapter 2.

Still, democracy is at least meant to provide us with a way of collective decision-making. Of course, collective decisions are made in various ways – sometimes by mob and frenzy. In November 1938, Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, occurred in Germany. It was so named because Nazi mobs smashed windows and set fire to Jewish homes, shops and synagogues, murdering and terrorizing, leading eventually to the destruction of 6 million Jews, an attempted genocide. Small groups have sometimes sought to impose their will on society regarding certain heated matters. Stirred by raving ignorance, some individuals acting together have, for instance, assaulted paediatricians, thinking them paedophiles. In South Wales, in 2000, Dr Yvette Cloete, a paediatrician, fled her home after it had been attacked, with some ‘paedo’ wording daubed on walls. There are different ways of collective action; at least the democratic way is intended to be peaceful – well, in physical action if not in political rhetoric.

The democratic machinery, to be democratic, needs to respect some version of universal adult suffrage: that is, the right of all adults (with a few exceptions) to vote. Obviously, there is the requirement for votes, but there is also the requirement for vetoes; the majority vote would not be permitted to overturn the universal adult suffrage, though it sometimes tinkers at the edges. Those vetoes are not the result of democratic votes. They set the framework within which democratic voting operates. Liberal democracies seek to harmonize majority voting with protection of minority rights – and that protection is justified by reference to morality, by, for example, how people deserve some degree of equality with regard to respect.

DEMOCRACY’S IMMORALITY

Why do we need a democracy? There would be no problem, were we all of a like mind; but we are not. Democracy comes to the rescue – so it seems. Everyone can have a say – and the outcome rests on majority votes, one way or another. There is present, though, a resultant deep immorality.

In committing yourself to democratic outcomes, you are giving blank cheques to you know not what. In our much-beloved democracies, we usually reach decisions, or appear to, by majority votes; in one way or another, literally or metaphorically, we raise hands. Yet we sink into confusion when the majority of hands is for what is wrong. After all, the majority could vote for me to do everyone’s ironing or for a minority to be enslaved or for racial segregation. That everyone’s preferences should count equally fails to guard against such injustices.

Commitment to whatever is the democratic outcome, without caveat, is thus highly immoral. As steps to avoid that immorality, even the most ardent lovers of democracy recognize that democracy as majority voting requires restrictions; even the most ardent lovers of democracy know that we can have too much democracy.

The democratic appeal has often been to autonomy, to self-government; the people rule themselves. Unless we engage some fancy footwork, we should judge that claim of self-rule as risible, as a deceit, an immorality, once we focus on individual voters. After all, I am scarcely governing myself if, as a result of elections – in which, yes, I participated – policies which I opposed in my voting are now ruling my life. There is, though, as already hinted, some fancy footwork in Rousseau’s Social Contract: ‘… every person, while uniting himself with all… obeys only himself and remains as free as before’.

Thus it is that Rousseau is often praised for his recognition of people’s need for freedom, to govern themselves, yet he is also often condemned as authoritarian and totalitarian. Why? Well, recall the General Will, that Will to which majority voting magically manages to give voice, and which aims at the best interests for all. Some people may reject the resultant policies of the Will; hence – and here comes the footwork – they need, argues Rousseau, to be forced to be free, forced to do what is truly in their own interests, even though they fail to recognize their true interests. That, paradoxically, is true freedom, true autonomy, despite people feeling that they are being coerced, that the government possesses too much authority over their lives and, if totalitarian, totally dominating nearly everything they do.

We may keenly join in the condemnation of Rousseau’s ‘forcing to be free’, but, as we shall see in Chapters 4 and 15, perhaps what is more pernicious occurs when State and corporate manipulations lead people to believe that they are acting freely and acting in their own true interests, when they are not.

Bringing Rousseau’s General Will down to earth, some may argue that at least there is something that is in the interests of one and all and the community as a totality; that something is living within the democratic structure. The democratic structure requires and preserves an equality of respect for all, a recognition that all (with a few caveats) have the right to participate in civic life, to take part in elections and so forth. Democracy consequently has to place some limits on what may be enacted by ‘the people’ to maintain the basic democratic credentials; democracy, as said, requires a non-democratic grounding. Let us note how only after significant protests, outside of voting – of extra-parliamentary action – have democracies shown genuine interest in voting rights, minorities’ rights, and, now, climate change – stirred in 2019 by Swedish schoolgirl Greta Thunberg.

Western democracies, as a matter of fact, have cohabited with all manner of immoralities. The United States’ Declaration of Independence was seen as compatible with slavery; George Washington owned slaves. Even today the United States democratic practice makes it difficult in some areas for African Americans to vote. Britain, that great beacon of democracy, up to the late 1960s allowed boarding houses to display signs declaring ‘No Blacks; No Irish; No dogs’, without embarrassment.

There needs, then, as already noted, to be a structure to a democratic community that protects minorities – and indeed majorities – which in some way provides equality of respect. The structure, in theory, is not open to democratic change, though even here we encounter political manipulation. Witness how the judges of the United States Supreme Court are appointed by the president; those political acts can set the tone for decades regarding certain rights, such as access to abortion facilities, assisted dying et al. The idea that the law, once set – even if part of the democratic structure – is free from political engagement is a myth. That, of course, raises questions of how members of the judiciary should be appointed; such questions were high on the political agenda in 2018, with the toing and froing over President Trump’s eagerness for the appointment of the conservative and controversial Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

Even with restrictions on what a democratic vote may permit, paradoxes still arise. Some voters – and politicians – may genuinely support the democratic procedures for decision-making, yet may also sincerely believe that abortion and euthanasia are deeply morally wrong, akin to murder. If the democratic machinery churns out the result that duly leads to the legalization of abortion and euthanasia, their psychological state must surely be distressed and in something of a quandary. There is blatantly a conflict between their belief that a democratic outcome should be respected and their belief that the outcome allows murder.

There is also a paradox regarding voting, when one knows that the result is not going to be close. Why then vote? That is a good question for any particular individual to address – maybe better to spend the time doing that ironing again or reading philosophy or visiting an elderly aunt – though, paradoxically of course, if everyone reasoned thus, there would be few votes.

TWO CHEERS?

E. M. Forster, the English novelist and humanist, gave democracy two cheers, one for its permitting variety and one for its permitting criticism. Those features may indeed be of considerable value, allowing some degree of self-expression to people – and that is emphasized by exercising the right to vote. Thus, voting may have value, though it is a curious value, as the outcome has little to do with how numerous individuals have voted and many people find themselves in servitude to what the democratic machinery delivers. Despite those defects, some argue in favour of the value of democratic deliberation and participation. People engage with each other, views are batted to and fro, and possibly some views are changed for the better; sensitivities can be improved regarding the plight of others. That optimistic rendering of election periods of course is rather illusory: just take a look at the popular press.

In Britain, in 2016, the Daily Mail’s front page sported ‘Enemies of the People’ over photographs of three High Court judges who ruled that Parliament’s consent was required for Britain to leave the European Union. In 2017, there was The Sun’s headline ‘Don’t Chuck Britain in the Cor-Bin’, as an attack on the Labour Party’s leader Jeremy Corbyn. In the United States in 2016 the New York Daily News ran the headline ‘Drop Dead, Ted’ as a response to Ted Cruz challenging the social values typically found in that city, values such as support for abortion and same-sex marriage. There are numerous such cases.

Even if deliberation and participation possess some intrinsic value, they are not of much use in securing valuable democratic outcomes. In fact, democracy may have poor instrumental value in achieving good and stable government – after all, politicians, to secure election, typically appeal to voters’ short-term interests. Plato saw voters as easily swayed by demagogues – that is, by leaders whose popularity results from exploiting people’s ignorance and prejudices. Aristophanes, a fifth-century BC comic playwright, also of ancient Athens, wrote the Clouds in which the so-called Inferior Argument, consisting of lies and bribes, wins the popular vote. Voters are also fickle. The Athenians one day voted to put to death the men of Mytilene, Lesbos, ordering soldiers to set off across the sea to effect the task. The next day the same Athenians opted for leniency, ordering another ship, carrying the changed policy, to catch the first. Happily, it did so – just in time.

Although democracy in itself may fail to secure good government, it may aid some degree of stability through acquiescence; voters buy into the belief that they have engaged in the process that has led to the government – and it is true that they have engaged, but many pointlessly so. It is worth reflecting on the following line. Belief in democracy as a good means of government may be self-fulfilling to the extent that good government requires citizens’ acceptance. Citizens typically do accept democracy as the least bad form of government, being in line with Churchill’s quip: ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.’

At least democracies offer some degree of risk to politicians: the risk of political death. That should offer us hope for some humility from them, though in most cases it is not a well-founded hope. Rather, it is more an incentive for them to offer whatever they think will secure their election. Democracy can sometimes humble leaders – but so can fear of revolutions. Democracy usually achieves the humbling, when it does, in less violent ways.

A MYTH BY WHICH WE LIVE

We may ask the question of why should we – ‘the people’ – accept that the government has the right to govern? Democracy provides an answer: we have voted for it. Curiously, we accept that, even though we know it is highly misleading. We could give a different answer to the question: the government has a right to govern because it has served us well – yet that government could be a non-democratic government, but one that is knowledgeable and well-motivated.

That latter answer may be understood as assuming that there is a single answer to the question of what is best for society overall. As we have seen, though, there is no good reason to think that is so. True, it is possible that there exist some minimal structural conditions best for all – for example, as already mentioned, some commitment to a certain equality of rights and of respect – and democracies often, as a matter of fact, are to some degree recognizing them.