19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Face to Face With the True Future of Business

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

MORE PRAISE FOR SETH LEVINE AND ELIZABETH MACBRIDE'S THE NEW BUILDERS

“Across various chapters of my professional career, one of which as head of Investment and Innovation of the U.S. Small Business Administration, I've seen first hand the seismic changes our entrepreneurial economy is going through. The New Builders perfectly captures these important and interconnected trends – trends that many people fail to see.”

—JAVIER SAADE, Former Associate Administrator, Chief of Investment and Innovation, U.S. Small Business Administration

“As a woman entrepreneur in a field dominated by men, I know what it's like to have to work harder to be taken seriously and to win respect. Women have power, as these stories make clear. They don't need it lent to them. They need and deserve a fair shot – and we'll all benefit from giving them one.”

—EVA SHOCKEY BRENT, Author, TV Personality, Bow Hunter, Conservationist

“The New Builders is a masterpiece of investigation and insight. Joe Biden and everyone in his administration needs to read this book NOW! It is both an inspiring and troubling glimpse at the changing nature of entrepreneurship in America.”

—DAVID SMICK, Global Macro Hedge Fund Strategist and NYT Bestselling Author

“Pay attention to this book: Entrepreneurs may not look like you expect them to, but they're always at the forefront of where we need to go, next.”

—JIM SHOCKEY – Naturalist, Outfitter, TV Producer and Host of Jim Shockey's Hunting Adventures and UNCHARTED on Outdoor Channel

“Elizabeth MacBride and Seth Levine have done it again! Discerning fact from fiction and really getting to the heart of how the 21st century entrepreneur is thinking and responding in the ever‐evolving landscape of “innovation ecosystems” domestically and globally. This is a must read book for those intrigued or looking to better understand how entrepreneurs and small business owners will ultimately reinvigorate the American and Global economy in a post COVID‐19 landscape and channel the spirit of America's Founders whom were the original entrepreneurs that founded one of the greatest countries of modern history…”

—G. NAGESH RAO, 2016 USA Eisenhower Fellow

“As entrepreneurship becomes democratized, the characteristic of entrepreneurs is rapidly changing. Seth and Elizabeth do a brilliant job of explaining these changes by telling specific stories of the next generation of entrepreneurs in The New Builders. Anyone who cares about the future of entrepreneurship, or the future of the American economy, needs to read this book.”

—BRAD FELD, Foundry Group partner, Techstars co‐founder, author of The Startup Community Way

“We're about to experience a profoundly different and exciting economic future – one where community will matter more than ever. This book is an essential guide to what's ahead for anyone who cares about reinventing the American economy.”

—ELAINE POFELDT, journalist and author, The Million‐Dollar, One‐Person Business

“Entrepreneurs translate society's values into reality. The New Builders is a fascinating (and heartening) window onto the next generation of entrepreneurs and the products and services they're building in communities across the country.”

—FELICE GORORDO, CEO of eMerge Americas, Miami

“Thanks to Seth and Elizabeth for this clear, concrete roadmap on how to drive entrepreneurship and innovation in the U.S. economy. Their stories and messages show how the face of American entrepreneurship is changing and how entrepreneurs on Main Street are key to job growth and prosperity. I hope the new team in Washington checks out “New Builders” and follows many of its recommendations.”

—AMBASSADOR JOHN HEFFERN (ret), Fellow, Georgetown University

“Elizabeth and Seth have uncovered the power and unlimited creativity of the human brain personified by the new generation of creators helping a new ecosystem which will conquer this planet…Inspirational to all including governments and their leaders. It tells you how to take and give and shows how to embrace the philosophy of problem solving rather than complaining.”

—ZAHI KHOURI, Palestinian/American entrepreneur and philanthropist

“The vitality of Lancaster City is in larger measure because of its New Builders, the mosaic of peoples from across the globe who have made Lancaster their home – whether in the 1600s or the 2000s. To see this concept reflected by MacBride and Levine is to understand what is special about our city – and no doubt, many others.”

—DANENE SORACE, Mayor of Lancaster, PA.

“Journalists who write about the Arab region tended to cover stories of conflict, security, destitution and hardship. The region is so much more than that. Elizabeth decided to write a different narrative, about the opportunity and hope in entrepreneurs who are innovating and driving change. I would argue that many of those stories became known because of her tireless efforts. Now, she and Seth Levine have turned a similar, powerful lens on New Builders in the United States – I can't wait for these stories to be known, too.”

—DINA SHERIF, Executive Director, MIT Legatum Center for Entrepreneurship & Development, and Partner, Disruptech

“Leveling the playing field for all entrepreneurs is crucial to our country's economic future. The increasingly diverse and dynamic people starting businesses today are closing the opportunity gap and developing innovative products and services to address some of our most pressing problems. The New Builders brings their stories to life. It is critical reading for anyone who wants to understand the future of business in the United States.”

—STEVE CASE, Chairman and CEO of Revolution, LLC, Co‐Founder of AOL, Founding Chair, Startup America Partnership

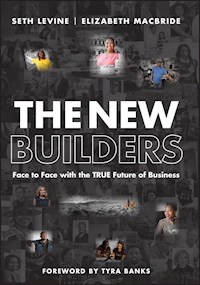

THE NEW BUILDERS

Face to Face with the True Future of Business

SETH LEVINE

ELIZABETH MACBRIDE

Copyright © 2021 by Seth Levine and Elizabeth MacBride. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 646‐8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e‐books or in print‐on‐demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 978‐1‐119‐79736‐4 (Hardback)ISBN 978‐1‐119‐79738‐8 (ePDF)ISBN 978‐1‐119‐79737‐1 (ePub)

COVER DESIGN: Paul McCarthyCOVER IMAGES: All Photos Considered Photography | Allie Atkisson Imaging | Photo Portfolio, Highlights | Cathy Sachs | Claire Hibbs‐Cheff | Donald “Diz” Zanoff | Emil Kuruvilla | Eric Elofson | Rope Line Media | New Hampshire Community Loan Fund | Montgomery County Chamber of Commerce | Philip Vaughan Photography | Scott Suchman | Seth Goldman

For Greeley: Love. Always.

and for Sacha, Addy, and Amanuel – our New Builders

_____

For Lillie and Quinn

My marvelous daughters

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

FOREWORD: OWN YOUR FIERCE POWER

Becoming an Entrepreneur

Power Moves

INTRODUCTION: THE REBIRTH OF THE GREAT AMERICAN ENTREPRENEUR

PART I: Who are the New Builders?

CHAPTER ONE: A New Generation

The New Builders

Entrepreneurs Are Everywhere

Hope

Choosing What to See

What Is an Entrepreneur?

Silicon Valley and the Rise of the Giants

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER TWO: How Change Really Happens

Main Street USA

How Big Became Beautiful

Why a Dynamic Economy Is Important

Innovation Comes from Surprising Places

Can You Tell an Innovator When You See One?

Innovation and Invention; Entrepreneurship and Science

The Easy Story of the Big Movers

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER THREE: The Definition of Success

Entrepreneurial Dreams

The Great Disappearance

It's About Capital. Hard Stop.

Note

Endnotes

CHAPTER FOUR: More than Grit

Relentless Pursuit

Doing What It Takes

Ghost Startups

Sometimes It's the Journey That Counts

Endnotes

PART II: How We Got Here / What We're Up Against

CHAPTER FIVE: Opportunity When You Don't Expect It

Note

Endnotes

CHAPTER SIX: A Brief History of Entrepreneurship in the United States

Part Myth, Part History

Entrepreneurial from the Beginning

The Age of Exploration

Colonial Ingenuity

The Business of Revolution

The Revolution of Business

The Land of Opportunity. For Some.

Starting Over versus Failing

Collaboration Thrives

The Dawn of the Internet Age

Venture Capital Is Born

The Silicon Valley Version of Entrepreneurship

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER SEVEN: The Elephants in the Room

Go Big or Go Home

Where Did Our Love Affair with Size Come From?

Big and Politically Powerful

Signs of Change?

Who Can Fight Back?

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER EIGHT: Where's the Money?

Women‐Owned Businesses Are Our Single Biggest Potential Source of Economic Growth

A Different Flavor of Iced Tea

The Nexus of Capital, Network, and Culture

Grassroots Growth

Capital Matters

Banks

The Slow Decline of Community Banks

More than Just Capital

Note

Endnotes

CHAPTER NINE: Failure, a Hallmark of Builders New and Old

Are We Starting to Fail at Failing?

Redefining Failure

Institutionalized Failure, in a Good Way

Teaching Resilience

Note

Endnotes

PART III: The Invisible Army

CHAPTER TEN: Unlikely Heroes

Notes

Endnote

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Crossing the Divide

Big Prairie and Open Pastures

An Uphill Climb

Fights That Don't Exist

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER TWELVE: Sum of Our Parts

Beauty Matters

The Old Boys Network Put to Good Use

Proudly Supporting “Lifestyle Businesses”

The Stonewall Jackson Sign Finally Falls

Endnotes

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: No One Develops on the East Side

It Takes Money

The Death of the American Bank

Financial Giants

Redlining Is Real, Even Today

“That Evil Woman”

The Forgotten Hero of Community Finance

Fewer Loans and Higher Interest Rates

The Relationship Factor

Endnotes

PART IV: Face to Face with the Future

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: A Secret of Silicon Valley

No One Does It Alone

Serendipity

Focus on the Numbers

Two Times More Likely

Metcalfe's Law

Notes

Endnotes

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: New Capital Models

Financing at Scale

The Definition of Investor and Financier

Connecting Investors with Main Street

A Trailblazer 40 Years in the Making

A Laboratory for Innovation

New Builders Supporting New Builders

A Call for Creative Finance

Endnotes

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Hope and Promise

See New Builders and See Ourselves

Change Starts with Individuals, but Collective Action Is What Really Matters

Safety Nets and Backstops

Rebalance Regulations to Help Small Business

Create a Movement of Support for New Builders

Broadening Capital Ownership

Why Should You Act? Because Communities Matter.

Note

Endnote

EPILOGUE

Endnotes

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

INDEX

PHOTO INSERTS

END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Guide

Cover Page

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

i

ii

iii

vii

viii

ix

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

61

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

FOREWORD: OWN YOUR FIERCE POWER

Wow, what an innovative concept. I love this.”

“I've never heard of anything like this before. It's so creative…so thoughtful.”

“It's genius. I believe in it and I believe in YOU.”

Beautiful words, right? Ego building. Pride boosting. Words every budding entrepreneur wants to hear.

Wrong.

Because after all of that praise comes… Nothing.

Welcome to my world. OUR world. I don't invite you in to garner pity. But I thank you for RSVPing to the plain, hard truth – the truth that I and so many have to endure. Yet still we rise and rise again because we believe – no, scratch that – we KNOW that what we have to offer society can truly change the world.

But how do you change the world when someone won't even lend you the change from their pocket?

There are many kinds of beauty in the world, many kinds of entrepreneurs, and many kinds of power. I'm a New Builder. I'm a Black woman, with decades of experience across industries, launching new businesses and working on new next‐level ideas.

But just like it is for many New Builders, the struggle to raise money is real. I have watched my White, male peers raise serious capital with ease, with ideas that are far less developed. And I know what you may be thinking – but just because my name may appear on billboards doesn't mean business boards respect my business acumen. And nor should they. Celebrity does not automatically equal a sharp business mind. But mine is. And so are the minds of so many New Builders, yet we struggle to be taken seriously because we don't fit that mold of what an entrepreneur “ought” to look like.

Entrepreneurship, for me, is not just about financial success. It's about leaving something that lasts beyond my time on Earth. A true legacy. From expanding the definition of beauty to teaching personal branding at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, I believe my profit must have a purpose. My companies reach people around the world and delight, entertain, and educate them in out‐of‐the‐box ways. We are obsessed with storytelling, and everything we do must have some funny, some fierce, and lots of heart, whether it's a worldwide television franchise or a tasty food product.

You've been reading my words for a bit now, so speaking of food, I think you deserve a treat. What about a scoop of ice cream? And what if I hid a yummy, chunkalicious, Surprise in it?

Okay, while you enjoy your ice cream, let's get back to business.

Becoming an Entrepreneur

When I was a model, I answered to the people behind the camera. But I always wanted more than that. I wanted control. Every single day of my modeling career, I encountered prejudice because I was Black or because I was curvy. People said I couldn't do this runway show, or couldn't be on that cover, or star in that campaign. I heard a lot of “no” and “you can't” and even “you'll never.”

Oh, it hurt. Bad. I cried. Lots. But I'm happy to say, it didn't break me. The tears turned to hunger – a famished feeling in my tummy to show naysayers that I could and I would. (I can hear the “models don't eat” jokes running in your head right now, but I was the rare one who lived off of barbecued ribs and coffee ice cream milkshakes. And I was carrying about 30 pounds more body weight than my colleagues. Oh yeah.) I was also eager to show people that my skills expanded way past runway walking and magazine posing. And yes, when I spoke those aspirations aloud, the “nos” from the powers‐that‐be flowed again.

But I'm writing this Foreword, so we all know that those “heck, nos” turned into some “hell, yeses.” Without struggle there is no progress, said Frederick Douglass. And without progress, there is no power. Entrepreneurship is a way to create and hold onto your own power. Your fierce power.

Power Moves

I have messed up a lot through all this. And learned plenty of what‐the‐heck‐was‐I‐thinking lessons that I now excitedly pass along to others. One of my favorite things to do is mentor young entrepreneurs over a hearty lunch while I teach them how to draw strategic mind maps to chart the path to their B.F.O.G.s – their Big Fierce Outrageous Goals.

Here's a bit of what I tell them:

Different is better than better.

Tiny improvements on someone else's product or service ain't gonna get you far. What about your business is unique? And don't force a unique narrative when you know you're derivative. VCs and PEs see straight through that… and you.

Hone your personal brand.

People don't just invest in companies, they invest in people. What's your personal origin story? What do you stand for? How are you letting the world know that? You're competing with so many others for capital, community, customers, and team members. The clearer you are about how you want to present to the world, the more ownership you have of your own narrative and the more attractive you become to attract others.

Find some shoulders…to cry on.

Entrepreneurship is no joke. Wins, losses, setbacks, unpredictable craziness…. You need someone you can just be vulnerable with. You also need that someone who shakes you and says, “Okay, enough with the wallowing in self‐pity. Get your butt up. Get your funky butt in the shower. And then get back at it!” This “E‐life” is damn hard sometimes, but don't easily give up or stop trying. Life has no mercy on you when you stop stepping up. And if you're not experiencing failure in your work life or business, you're playing it way too safe. Shake it up and take a risk…and yes, a shower, too.

Make freezing‐cold calls.

Reach out to people who inspire you. Keep it short and to the point. Compliment them on something recent they've accomplished and give it context on how it has inspired you. You just may get a mentor out of it. That's how I established a meaningful relationship with somebody we lost this year, Tony Hsieh. I was obsessed with his book,

Delivering Happiness

, and picked up the phone. That cold call turned into a rewarding mentoring and business friendship. I miss him. We all do.

Reward people who disagree with you.

One thing that terrifies me is a

yes

person. Where everything I think up is perfect and flawless and they would never dare disagree with me. Yikes! Just writing about this type of person feels like a horror movie to me. In meetings, I often insist on hearing dissenting voices. About 50 percent of the time, there's a nugget (or a boulder) of truth that positively influences some of my decisions.

Turn up your mic.

Reach out. Speak up. Make yourself heard and seen. Don't sit there and say, “I'm going to work really, really hard and one day they're going to notice.” Because they won't. They're not thinking of you. Make them.

Hope you enjoyed my tips. Oh … how's that ice cream tasting? Magnificent? Wonderful. It's from my new business, SMiZE Cream. And yeah, you heard me say this already, but the “nos” thrown my capital‐raise‐way were dizzying.

I pitched my ice cream business to this one investor, and even though I felt beaten down by all the passes, I pitched with all of my heart and soul. I shared how we are not just an ice cream company but that we are in the business of goal setting and goal getting and teaching others how to be the same. That we don't just scoop an amazing‐tasting super‐premium frozen treat, but that we are an IP company with a suite of revenue streams that don't just bring in the bucks but delight customers to the max and help them make their dreams come true, too.

“Wow, what an innovative concept. I love this.”

“I've never heard of anything like this before. It's so creative…so thoughtful.”

“It's genius. I believe in it and I believe in YOU.”

And then he said, “I'm in.”

What?!

Okay, okay. So he didn't say those words exactly, but pretty close. But the point is, he said “yes”! And his yes was so refreshing. This guy wasn't full of empty, ego‐stroking words. He didn't flatter me. He saw me. I spent months digging into the details with him, and the idea evolved into one with true enterprise potential.

New Builders like me need to be seen for our true power. That's why I'm so happy to be connected to them in this book – all of them across the country, through this tome you hold. And I say to all of them, when they're judged unfairly for the color of their skin, or the shape of their body, or any damn thing else, find that shoulder, let the tears flow, then get your shower and go pitch again and again and again. The world is changing. And you are a part of that change. The world needs your idea. You can change the world.

And you know who else can change the world? The financial community peeps who have the big bucks to enable, support, encourage, and uplift the change makers. How do they do that? By not trying to just be better. But by being DIFFERENT. Seek out entrepreneurs who don't look like you. When they have a product or service you don't quite understand, don't pull in the one person who looks like them from your office expecting them to be an expert. Dig deeper. Staff up your team to culturally represent and be able to identify opportunities that are outside of your own reach and understanding. The world needs your leadership to make real change.

Now, back to the man who lent me the change from his pocket for my own biz. He is the co‐author of this book. Yep. Hi, Seth. Thank you so very much for seeing my power.

Okay, back to you, reader. Turn the page. And experience how, together, we can turn the world around. Elizabeth and Seth, thank you for giving voice to this community, to these amazing change makers, to these New Builders.

–Tyra Banks

INTRODUCTION: THE REBIRTH OF THE GREAT AMERICAN ENTREPRENEUR

The definition of success in America today is increasingly corporate, built around the concepts of growth, size, and consumption. Big companies – large in terms of revenue, profits, and mindshare – frame the way we think about what is important and powerful. But our current overweening love affair with big poses a fundamental problem for America and what has been our uniquely dynamic economy. In this environment, entrepreneurship is dying. We've lost touch with the critical part of our society that is created by smaller businesses, which are responsible for much of our innovation and dynamism, most of the job growth, and produce nearly half of US Gross Domestic Product. Where entrepreneurship is thriving, it is so narrowly, among brash, young, typically White and male, technology company founders on their way to becoming big.

The needs of most entrepreneurs and small business owners are increasingly being overlooked and, as a result, they are being left behind in the economy and left out of the conversation. Entrepreneurship in the United States has declined over the last 40 years. As we narrow our definition of entrepreneurship, we narrow our opportunities and limit our economy.

It doesn't have to be this way.

The future is always coming to life somewhere. Luckily for us, we happened to be witness to it.

In the summer of 2019, we – Seth Levine, a venture capitalist, and Elizabeth MacBride, a business journalist – set out to tell the stories of entrepreneurs beyond the high‐tech enclaves we both know well. What did entrepreneurs look like in the middle of America and in communities outside the halo of traditional technology startup hotbeds?

What we discovered surprised us. The next generation of entrepreneurs doesn't look anything like past generations, and defies the popular image of an “entrepreneur” as a young, white founder, building a technology company. In fact, almost the opposite is true. Increasingly, our next generation of entrepreneurs are Black, brown, female, and over 40. They are more likely to be building a business on Main Street than in Silicon Valley. They typically start businesses based on their passions and rooted in their communities. In many cases, they are building businesses in areas left behind after the uneven recovery that followed the Great Recession of 2008–2009.

In this book we tell the stories of a wide range of entrepreneurs, from a man who revitalized an entire community through sheer stubbornness, to a family of guides in the Montana wilderness, to the first chocolatier in Arkansas, to a baker for the Dominican community of Massachusetts.

We call these entrepreneurs New Builders. They are the future of America's entrepreneurial legacy. This book tells their stories and explains the financial systems and power networks that must change if we are to help them succeed.

Yet, when we took our initial findings to our peers in the worlds of venture capital and journalism, people didn't believe us. They thought, based on what they saw about entrepreneurs in the news, that entrepreneurship in the United States was thriving. Most people have missed the fundamental changes that are taking place in our entrepreneurial landscape. As the people starting businesses have changed, our systems of finance and mentorship have failed to keep up. For the first time in history, the majority of entrepreneurs don't look like either the past generation of entrepreneurs or the people who control the capital and systems of support that are enablers of entrepreneurship.

New Builders are a diverse group, but they share one trait: they don't fit the mold of corporate success. In a business world that increasingly values conformity, New Builders defy it.

But being overlooked is a superpower of New Builders. Because of racism, sexism, and ageism, or because they saw ways to create new systems outside the ones they couldn't change, many New Builders turned to entrepreneurship – starting businesses and creating successful lives on their own terms. They often start businesses based on their values, and they are unusually resilient, possessing an extra dose of grit and determination.

New Builders are disconnected from the systems that accelerate new businesses and propel business growth. Those systems were built for past generations of entrepreneurs. New Builders are undercapitalized, and when they try to access networks that control capital, they often face systemic racism and sexism.

Entrepreneurs have been the bedrock of American business since before our country was founded, and entrepreneurship is deeply rooted in our country's history. Entrepreneurs were the women and men who explored and settled the vastness of the United States, and who built the infrastructure that stitched it all together – from rail, to industry, to the internet, to the goods and services needed for our everyday lives. But unlike past generations of entrepreneurs, who upended yesterday's big companies, today's New Builders don't have the support they need to be the dynamic engine of our economy. The Covid‐19 pandemic unfolded while we were in the midst of writing The New Builders, accelerating trends already in motion and bringing the harsh reality of our country's declining economic dynamism to the surface. When the final numbers are tallied, we will have lost millions more small businesses from what was already a shrinking base.

But New Builders' optimism is infectious, and their success in the face of obstacles gives us hope for the future of small companies and their crucial role in the American economy. In The New Builders, we argue for a better future. One that celebrates and supports the next generation of entrepreneurs and creates a more dynamic, egalitarian, and equitable society.

Our economic future lies in some surprising places – surprising only because we cling to a mistaken narrative of entrepreneurship. America needs a resurgence of these small businesses and the entrepreneurial spirit they embody, especially as we emerge from the Covid‐19 economic crisis. Renewal and change come to life in small companies – from Main Streets to office parks, from kitchen tables to back‐alley garages.

In The New Builders, we call for a new mission that embraces the next generation of American entrepreneurs. Just as Silicon Valley was born out of a national mission to embrace mid‐twentieth‐century innovation and expand democracy's reach around the world, so too must we come together to build a network of support for our next generation of entrepreneurs. New Builders will play a critical role in helping rebuild communities, and in so doing will help bring forth a new vision for the United States. New Builders are not add‐ons to our mental map of business in the United States. They are the map.

In our time meeting and interviewing New Builders, we found compelling examples of new networks and support structures springing up across the country. But those efforts need to be expanded, and too many focus on changing New Builders to adapt to the existing system, rather than on adapting the system itself.

New Builders are the bedrock of the economy and the strongest part of the fabric that holds our communities together. Individually, they are strong; together, they are mighty. Their resolve – and ours – was tested in 2020 and 2021 as the pandemic raged across the country. This resolve will continue to be challenged. In this book, you will meet many New Builders and in doing so, gain a glimpse into the future of American business.

Our focus is on the amazing individuals we call the New Builders. Their stories offer hope and promise. Their passion, dedication, and grit inspire. We hope The New Builders makes you think differently about entrepreneurship, about the businesses you support, and about the policies that help drive our economy. Perhaps this book will invite you to consider the role you might play in supporting New Builders in your community.

Fundamentally, this book describes the urgent need for those with power in our society to change their thinking and their actions. We all benefit by creating a more robust society where a greater number of people have access to the capital and know‐how necessary to create and grow businesses.

Most of all, we hope this book inspires you with the potential for our shared future.

–Seth Levine–Elizabeth MacBride

PART IWho are the New Builders?

“This is not just a grab‐bag candy game.”

Toni Morrison

CHAPTER ONEA New Generation

Danaris Mazara opened the door at Sweet Grace Heavenly Cakes the day after the governor lifted the Covid pandemic lockdown on “nonessential” businesses in late May 2020.

“Thank God,” she said. Her 12‐year‐old bakery, which had been conceived of when she was lying on her couch staring at the ceiling with $37 to her name, was back in business.i

Eight women were already back at work on Essex Street in Lawrence, Massachusetts, making cakes in the back of the shop. The Sweet Grace bakers turned out cakes, from five silver‐festooned tiers for a wedding to two‐layered dreamy dark and milk chocolate affairs. On any given day, a cake as grand as a two‐foot‐tall Noah's Ark birthday cake, complete with a giraffe peeking over the top, might hold pride of place in the window.

It was a parade of life events, decked out in butter and sugar, for the Dominican community that Sweet Grace served.

Twelve orders came in the day before. But a week usually brought more than 100 orders. Danaris worried whether sales would be strong enough to make the payroll, the mortgage, or payments on the loan she had taken to expand late last year. She recalled what the space looked like before she remodeled it. Its transformation mirrored her own, from bankrupt and nearly out of money to business owner and community leader. The space had been dim and cluttered, with abandoned fixtures and trash left by the hair salon that was its previous occupant. Now it looked like it smelled – soft, sweet, and full of energy. But not as busy as it was before the pandemic and economic crisis hit.

“I think it's normal to be afraid,” she said. “You don't know what's going to happen in the future. I'm trying very hard to…” she trailed off. “Just wait and keep working,” she finished.

Around the corner, the family‐owned Italian bakery also opened its doors that morning. But unlike Sweet Grace Heavenly Cakes, it had been able to stay in business through the Covid‐19 shutdown because of a historical relic: it baked bread. Somewhere, somebody in the state's bureaucracy had decided that bread was essential. But not cake.

That's not how Danaris saw it. For people who love to dance and sing, and who live for their families and communities, cake is essential. Now, she wondered if everything she had built – for her family, her community, for her workers, and their families – would survive.

Danaris and her husband had arrived in Lawrence in 2002 from Puerto Rico. Born in the Dominican Republic, her mother had moved the family to Puerto Rico when Danaris was a young girl. There she had grown up and met her husband, Andres. Moving to the mainland after they were married, Danaris and Andres started their life in Lawrence, in her brother's attic. The room had no air‐conditioning, which meant it was sweltering in the summer, and had little insulation, leaving them to huddle together in the winter. But there were jobs in the factories in and around Lawrence, and the opportunity for a better life.

At the factory where she first found work, Danaris tried, tentatively, to speak a few words of English. “I didn't know that when people eat American chicken, they start speaking English,” mocked the assistant manager on the production line.

She was so humiliated she couldn't bring herself to go back the next day. Instead, she found a language school. The lessons paid off and when she eventually found another job, they were impressed enough to quickly promote her to assistant manager. Right before her daughter, Grace, was born, the Great Recession of 2008–2009 hit. Her husband was laid off from his job at Haverhill Paperboard, a local manufacturer that had been operating for over 100 years. The layoff cost 174 people their jobs and livelihood.

“I was very depressed because I had a newborn baby, something I was waiting to have for many, many years. But I couldn't stay at home to take care of her. I didn't know what I was supposed to do,” she told us.

Sweet Grace Heavenly Cakes was born in that moment of desperation, from the mind of a woman who, typical of today's entrepreneurs, had little in the way of resources, or even a well‐resourced network, to help. The bakery succeeded in the early days because of the help of an unlikely trio of benefactors: an Indian‐born billionaire, a Harvard‐educated tech executive, and a banker from Brazil. They were all engaged in programs to help Lawrence, a city of old and new immigrants, come back to life. In 2018, they had pulled together to help the city recover from a gas line explosion that destroyed 40 homes and caused the immediate evacuation of 30,000 people (from a city of 80,000). Now, as the Covid‐19 pandemic dragged on, Danaris wondered: if things were really bad, could she turn to them for help?

In better times, before the pandemic hit, Sweet Grace's reputation was so good, people lined up to pay $2 just for a cup of the crumbs. Even the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, whose office was menacingly outside the back door, sometimes stopped in for a cup.

“We have many customers coming from far, far away to get our cakes,” she said. “Dominican people, you have to know us. We are always celebrating.”

Danaris made it through seven weeks of pandemic closure by using her personal savings to pay both the mortgage on her house and the payments on her building renovation loan. She paid her employees – four of whom were women with children still back in the Dominican Republic – for a week. But she was stretched thin, both financially and emotionally.

She had been right before to trust in her ability to build a business. Her prayers had worked in the past. Now, she trusted they would again.

The New Builders

Danaris is a New Builder. She is one of the next generation of entrepreneurs defining the future of American business. These entrepreneurs are increasingly Black, brown, and female. Many are older than entrepreneurs of previous generations and, as a result, today's entrepreneurs are older than many people realize. They are talented innovators and businesspeople with an extra dose of grit. They're passionate about what they do, and their motivations are often more complex than our current definition of entrepreneur allows. They're apt to be driven by the idea of contributing to their community as much as by the idea of profit, though they often believe they can do both.

The entrepreneurs of today are a much broader group than the entrepreneurs that dominated our old mindset, the high‐tech founders of Silicon Valley and Boston. Very few New Builders have businesses that fit the idealized Silicon Valley model of fast‐growth, highly profitable (or at least highly valued) enterprises – but out of their ranks, we will find winners in the post‐pandemic recovery. You'll find them in places as varied as Main Streets, redlined communities, and technology parks everywhere. And they come up with ideas for their businesses not tinkering in the fabled garages of Silicon Valley but in teenagers' bedrooms and around kitchen tables. Some are building technology businesses with the goal of hyper growth. Most are not. If we want them to win in greater numbers, we need to understand better who they are and how to support them. Our idea of entrepreneurship has been overtaken by a particular myth – that important entrepreneurs are White, male, and Ivy League–educated, and that the only truly worthwhile businesses are software‐driven companies with the potential to grow into huge businesses. That image doesn't reflect the reality of entrepreneurship across America, or the fact that small businesses are not just a sentimental cause – they are critical part of our economy. It's time to take back the idea of entrepreneurship to include the incredibly rich and wide variety of businesses that are being started in America today. By not seeing New Builders, not supporting them and helping them thrive, we risk letting go of the entrepreneurial edge that has long set America apart from other countries.

The New Builders are out there. They're an invisible army, working to further themselves and their communities as they turn their business ideas into reality.

Entrepreneurs Are Everywhere

Danaris, like many New Builders, didn't come to start and build a business from a whiteboard or as part of a class exercise. It was her lived experience, combined with the kind of motivation that comes from the knowledge that you're not going to succeed any other way – at least, not on the terms you want. Quiet but forceful, and fiercely proud of her culture, Danaris spent years putting other people before herself, including her husband and her children. Like the mother who inspired her, she knows how to carry on through tears. But in the company of people from cultures where tears are a sign of weakness, she also knows how to hold them back. If you passed her on the street, you might not give her a second look. You almost certainly wouldn't think this Dominican woman was a community leader and small business owner.

In today's economy, an estimated 60 million people are entrepreneurial in some way. There were 5.6 million employer firms in the United States in 2016, the last year for which complete data are available. If you include the number of “nonemployer” businesses (sole proprietorships – what we now like to call “solopreneurs”) this share goes up to 98 percent. Overlapping with these businesses are the 57 million Americans who freelanced in 2018 as part of the gig economy.1

It's easy to underestimate the impact of grassroots entrepreneurs on the economy, especially in a country that's become consumed by a fast‐growth, high‐tech business narrative. But recent World Bank research found that it's almost impossible to predict which companies will eventually turn into “gazelles” – their term for firms that take off quickly, grow rapidly, and employ large numbers of people. High‐growth firms aren't just technology businesses (though some are). Nor are all startups in the classic sense. Rather, they are firms between one and five years old, and they're found in many sectors across our economy.2 Likewise, important innovations are as likely to happen in Danaris's kitchen – the low‐calorie cake she's been playing around with, for example – or a lab in the Midwest, as in the head of a Silicon Valley computer coder.

Early data suggest that the number of entrepreneurs is growing in the midst of the Covid‐19 pandemic, as people become entrepreneurial out of necessity. As the pandemic started, the average small business had just two to four weeks of cash on hand, a fact that explains why so many folded (already numbering in the several million, as of the time of this writing).3 Our economy needs more New Builders.

If the past is any guide, unless something changes, fewer and fewer Americans will choose to become entrepreneurs after the pandemic aftereffect fades. The long‐term slowdown in new business activity contributes to the phenomenon of what one might describe as ghost startups – businesses that never got started because the founders didn't have the opportunity to get their ideas off the ground. The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation calls them pre‐entrepreneurship leavers.4 We'll never know the names of these businesses, nor the impact they might have had on a local, national, or even global scale, unless we pause to recognize how many ghost startups our current economy is missing.ii

The startup rate in America, the share of companies zero to two years old, fell from more than 12 percent in 1980 to about 8 percent in 2015.5 Meanwhile, the number of people employed by small businesses – while still more than 40 percent of the workforce – fell by one‐third between 1987 and 2015. The Covid‐19 pandemic is exacerbating these trends and, at the same time, highlighting why small business entrepreneurship is so essential to our economy.

What we found as we interviewed dozens of entrepreneurs and small business owners – we use the terms almost interchangeably – across the United States is that several elements are merging to make it hard to be a New Builder.

The systemic racism, sexism, and ageism that pervades our culture means that today's entrepreneurs often don't get enough support. Our systems of capital and networks are dominated by White men, many of whom consciously or unconsciously look for other White men to invest in. But today's entrepreneurs are increasingly women and people of color. And many of our best entrepreneurs are older.

Consider:

Women will soon make up more than half of all business owners in the United States because the rate at which women are starting businesses is growing at more than four times the rate of business starts overall. And women of color are responsible for 64 percent of the new women‐owned businesses being created, making them the fastest‐growing segment of business owners in the United States.

The entrepreneurship rate in the United States has been driven by people of Hispanic origin, whose rate of entrepreneurship is almost twice that of the average of other groups.

6

Immigrants, as well, are twice as likely as native‐born Americans to start businesses.

The average age of the leaders of high‐growth startups is 45.

7

And the highest rate of entrepreneurial activity in the United States is among people aged 55 to 64.

8

Entrepreneurs can succeed in today's economy – you'll meet many in this book – but many are struggling because our business landscape has fundamentally changed. We find ourselves in an age dominated by big business and powered by software and the consumer movement. Our current business environment is driven by a pursuit for profit, above all else, and enforced by a government that, under both Democrats and Republicans, has increasingly shifted the rules of the game to favor size. Society has become obsessed with the ability to order any item at any time on demand, the convenience of everything under the sun being delivered to our front door, and the comfort of knowing that you can get the same coffee, burger, or taco in just about any large city in our country. We have started to devalue people who pick another path, who want to be producers, rather than consumers. Even among technology companies – which most perceive as thriving – fewer people are launching new businesses. Now is the time to focus on these changes and start to do something about them.

This long‐term decline in entrepreneurship has terrible implications for the health of our society. Twenty‐five years ago, a child born in the bottom 25 percent of the economic bracket had a 25 percent chance of making it into the top 25 percent. This was the basis for the American dream – through hard work, determination, and likely a bit of luck, anyone, regardless of the circumstances from which they came, could rise up the economic ladder. Today, someone born into the bottom 25 percent of the economic ladder has only a 5 percent chance of making it into the top 25 percent. The American dream is slipping away, and we're simply watching it happen.9

Hope

But this is fundamentally an optimistic book, because New Builders are optimistic people.iii In a cynical age, they still believe in the American dream. In researching and meeting New Builders, we found a group of people across the country engaged in building a new future for themselves, their communities, and, collectively, the country. We also discovered communities that are picking up the challenge of growing their own local support networks for these entrepreneurs. The people we met in researching this book show us how fulfilling it is to own a business, how meaningful it is to be part of a community of entrepreneurs, and how rewarding it is to be responsible for your own future.

We spend a lot of time in the United States today celebrating individual spirit, but also looking to the government for help. What we found is that most things of consequence today happen in the space between individuals and government, in relationships between people who create change, in new networks, and in communities that are leading their own revivals.

In the coming chapters, we'll explore places like Staunton, Virginia, which is home to a local angel network that has invested more than $1 million and is home to a makerspace that has helped rejuvenate the downtown. The story of the Staunton Makerspace shows what happens when the spirit of New Builders takes root in a community and is nurtured there. About a year after it was opened, a fire destroyed the fledgling operation in downtown Staunton. A 92‐year‐old former machinist, George Saugui, read about the fire in the newspaper. “I thought we lost everything,” Dan Funk, the founder of the Makerspace told us. “But he showed up.” The duo hoisted George's old workbench into a truck and brought it down to the ruined Makerspace. “He sat for four weeks, repairing all of our woodworking equipment,” Dan recalled. The Makerspace was rebuilt with the help of George and others in the community who turned up to rally around this important asset. It is now back in operation and has since expanded to include members working on a variety of hobbies, as well as entrepreneurial ventures in everything from textiles to 3D printing (which quickly became important during Covid‐19).

Indeed, entrepreneurs, especially those with unexpected success stories, have given the United States much of our identity as a nation of builders and doers, risk‐takers, and innovators, of economic prosperity and deep community identity. The story we tell ourselves about America, although part myth and part reality, is inexorably linked to this entrepreneurial spirit.

Choosing What to See

You've probably never heard of Elizabeth Keckley. Born an enslaved person in 1818 in Virginia, she learned a skill, dressmaking, which her White owners used to help support their families. As is the case with many women – especially Black women – the value of her work was not her own. Through sheer grit and determination, she scraped together $1,200 (roughly $35,000 in today's currency) and purchased her freedom. In 1860, she made her way with her son to Washington, DC, where she met and befriended Mary Todd Lincoln, becoming her personal modiste. She eventually chronicled their close friendship in her book, Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, a remarkable history of her escape from slavery and her time inside the highest echelons of American political society.

Hers is an almost unbelievable account of the power of the entrepreneurial spirit to change one's life and a testament to the determination required to succeed. It's also a reminder – and something we'll explore over and over as we meet more New Builders – of the power of network and mentorship. It's a story of promise and a beacon to this day for the power of American entrepreneurship. But it's also a reminder that New Builders and their predecessors have been fighting for hundreds of years for recognition and support in our entrepreneurial landscape. One of the reasons we don't value Danaris Mazara is that we haven't valued Elizabeth Keckley. Former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice – the first Black woman to hold that position – described this fight for universal dignity and respect that many dominant communities take for granted, but that others are in a constant struggle for, in a commencement address to the College of William & Mary in 2015:

I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, the Birmingham of Bull Connor and the Ku Klux Klan and church bombings, a place that was once quite properly described as the most segregated big city in America. I know how it feels to hold aspirations when your neighbors think that you are incapable or uninterested in anything higher…We have not and will not quickly erase the lasting impact of our birth defect of slavery, or the follow‐on challenge of overcoming prejudices about one another (emphasis added).10

Rice reminds us that our past is something that we can't, and shouldn't, simply forget or tuck away in some dark corner. At the same time, our history does not need to define us.

As in every other sphere of American life, racism and misogyny are critical parts of the story. Too many women and entrepreneurs of color have been written out of our entrepreneurial history – from the earliest days of our country to the present day. Immigrants played, and continue to play, a critical role in building America's entrepreneurial identity. The truth is that the entrepreneurial fabric of our country has always relied on women, people of color, and immigrants. They built great businesses and helped develop the diverse Main Streets that flourished throughout much of our history as a nation. To see the potential of present‐day New Builders, we need to understand how easy it has been to discount entrepreneurs who don't fit the prevailing model. Because now, more than ever, we need to recognize the role these diverse business owners play in our economy and change how we support and enable them. Our economy has always relied on the success of small businesses, some of which grow and others that stay small. But we're quickly losing sight of that and, in so doing, jeopardize not just our economy but along with it our national identity.

To understand how we got to this place, where we've nearly abandoned the people who are our best hope for building a better future, we need to start with a short trip into the past, on the shoulders of that too long, too complicated, and now seemingly co‐opted word: entrepreneur. We need to understand how, in the late twentieth century, Silicon Valley and the tech world became, first, the gold standard, and then the only standard that mattered for entrepreneurship. And we need to understand that our love affair with size is causing us to forget the power of small. We've also lost sight of one of the most inexorable rules of money: it will flow along the path of least resistance and highest return, which is often to the people who already have it.

What Is an Entrepreneur?

Entrepreneur comes from a French root, entreprendre, which means “to undertake,” according to Merriam Webster Dictionary. The modern concept of an entrepreneur is thought to have originated with French economist Jean‐Baptiste Say in 1800. In Say's telling, an entrepreneur is an “adventurer,” someone who “shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield.”

Even before Say, Richard Cantillon, an Irishman living in France at the time he published Essai sur la Nature du Commerce au General (Essay on the Nature of Commerce), referred to “entrepreneurs” as those who produce something at a fixed cost with the intention to sell it at an unknown price. He also referred to entrepreneurs as “adventurers,” which maps closely to the language that Say used and is perhaps where Say took his idea. Cantillon's book was likely the first to outline a complete economic theory – coming some 50 years before Adam Smith's more famous Wealth of Nations (Cantillon's book was published posthumously around 1750, but sections of the work were reportedly widely read in the 20 years leading up to its publication).11 Unlike Smith, who didn't mention the role of entrepreneurs in his seminal work, Cantillon placed entrepreneurship and the role of disruptors at the center of his economic theory. Cantillon was, in many ways, the pregenerator of modern economic theory as it relates to entrepreneurship. In his thinking, entrepreneurship stood at the center of economic activity and was the core from which broader economies developed.12

The first serious modern‐day academic to think about entrepreneurship was Czech economist Joseph Schumpeter, who identified people – “wild spirits,” he called them – who engaged in what he termed “creative destruction” in the business sector. It was these individuals who were responsible for virtually all of the innovation and much of the growth in the economies he studied. Schumpeter moved to the United States in 1932 and taught at Harvard University. His ideas of these wild spirits captured much of what America loved about small businesses of the middle of the century. He believed change came from individuals, from within. And the wildness he described suggested this entrepreneurial spirit could come from anywhere. Indeed, in his view, anyone could start a business and succeed. This idea fit nicely with the American ethos of the day and played directly into the long and deep‐seated narrative of America as a land of opportunity, a place of adventure and risk. It was a land where people were not bound by the circumstances from which they came, but rather, by what they made of their natural abilities. It suggested a certain boundlessness to opportunities and an ability to make or remake oneself. It played to Americans' love of risk and to our celebration of individualism.