6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This major new anthology of the minuet in the Nordic countries comprehensively explores the dance as a historical, social and cultural phenomenon. One of the most significant dances in Europe, with a strong symbolic significance in western dance culture and dance scholarship, the minuet has evolved a distinctive pathway in this region, which these rigorous and pioneering essays explore.

As well as situating the minuet in different national and cultural contexts, this collection marshals a vast number of sources, including images and films, to analyze the changes in the dance across time and among different classes. Following the development of the minuet into dance revival and historical dance movements of the twentieth century, this rich compendium draws together a distinguished group of scholars to stimulate fresh evaluations and new perspectives on the minuet in history and practice.

The Nordic Minuet: Royal Fashion and Peasant Tradition is essential reading for researchers, students and practitioners of dance; musicologists; and historical and folk dancers; it will be of interest to anybody who wants to learn more about this vibrant dance tradition.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

The Nordic Minuet

The Nordic Minuet

Royal Fashion and Peasant Tradition

Edited by Petri Hoppu, Egil Bakka, and Anne Fiskvik

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2024 Petri Hoppu, Egil Bakka, and Anne Fiskvik (eds). Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapter’s authors.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Petri Hoppu, Egil Bakka, and Anne Fiskvik (eds), The Nordic Minuet: Royal Fashion and Peasant Tradition. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Further details about CC BY-NC licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0134#resources

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80064-814-2

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80064-815-9

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80064-816-6

ISBN Digital eBook (EPUB): 978-1-80064-817-3

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80064-820-3

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0314

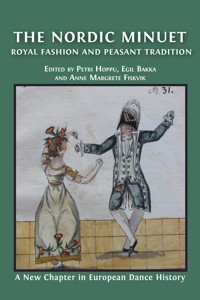

Front cover: Pierre Jean Laurent, Veiledning ved Undervisning i Menuetten [‘Guidance for Teaching the Minuet’], ca. 1816, Teatermuseet, København. Photo: Elizabeth Svarstad. ©Royal Danish Library

Back cover: Otto Andersson, Folkdans, Kimito ungdomsförening [‘Folkdance performed by the Kimito organization’], 1904. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, https://www.finna.fi/Record/sls.SLS+105+b_SLS+105b_66?lng=en-gb, CC BY 4.0

Cover design by Katy Saunders

Contents

Foreword

1. Introduction

Petri Hoppu

PART I: DEFINING AND SITUATING THE MINUET IN HISTORY AND RESEARCH

2. Situating the Minuet

Egil Bakka

3. The Minuet as Part of Instrumental and Dance Music in Europe

Andrea Susanne Opielka

PART II: REFERENCES AND NARRATIVES

4. Nordic Dancing Masters during the Eighteenth Century

Anne Fiskvik

5. The Minuet in Sweden—and its Eastern Part Finland—during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and in Sweden after 1800

Gunnel Biskop

6. The Minuet in Finland after 1800

Gunnel Biskop

7. The Minuet in Norway

Gunnel Biskop

8. The Minuet in Denmark 1688–1820

Anders Chr. N. Christensen

PART III: SOURCES ABOUT THE DANCE FORM AND HOW THEY WERE CREATED

9. Historical Examples of the Forms of the Minuet

Elizabeth Svarstad and Petri Hoppu

10. The Minuet in the Theatre

Egil Bakka, Elizabeth Svarstad, and Anne Fiskvik

11. Collecting Minuets in Denmark in the Twentieth Century

Anders Chr. N. Christensen

12. Collecting Minuets among the Swedish-speaking Population in Finland

Gunnel Biskop

13. Minuet Music in the Nordic Countries

Andrea Susanne Opielka, Petri Hoppu, and Elizabeth Svarstad

PART IV: THE MINUET AS MOVEMENT PATTERNS

14. Nordic Forms of the Minuet

Gunnel Biskop

15. Minuet Structures

Petri Hoppu, Elizabeth Svarstad, and Anders Christensen

16. New Perspectives on the Minuet Step

Egil Bakka, Elizabeth Svarstad, and Siri Mæland

PART V: POST REVIVAL—THE LATE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURIES

17. Minuet Memories and the Minuet among the Swedish-speaking Population in Finland today

Gunnel Biskop

18. Minuet Constructions and Reconstructions

Anna Björk and Petri Hoppu

19. New Forms and Contexts of the Minuet in the Nordic Countries

Göran Andersson and Elizabeth Svarstad

EPILOGUE

20. Some Reflections on the Minuet

Mats Nilsson and Petri Hoppu

List of Illustrations

List of Videos

Map of Locations

About the Authors

Index

The minuet is danced as a ceremonial dance at a wedding in Vörå, Ostrobothnia region, Finland, 1916. The minuet is danced by two couples at a time, with the bride and the groom on the left. Photograph by Valter W. Forsblom. The Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, CC-BY 4.0.

Foreword

©2024 Petri Hoppu et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.00

There has been a close cooperation within the Nordic field of dance for a long time. Among folk dancers, it has lasted for more than a hundred years. The organised folk-dance revival movement started in the 1880s and, in 1920, the first sizeable Nordic folk-dance reunion (folkdansstämma) was arranged in Sweden. The dancers met to dance together and to show their dances, and these reunions have been held mostly biannually since then. They continue into the present.

For nearly fifty years, dance researchers in the Nordic countries have met to study these dances, gathering at work meetings for joint discussions and research. It started in 1977, with the founding of Nordisk forening for folkedansforskning (Nff; The Nordic Association for Folk Dance Research). Researchers from all the Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and the autonomous regions of Åland and the Faroe Islands) have participated. The topic is social dancing in the Nordic countries, emphasising traditional as well as revival versions and contexts. Perspectives and methods from dance history and ethnochoreology are central, as is the analysis of movement patterns. In 1978, Nff started a membership publication, which has been published every year since.

The organisation Nff has around one hundred members, and a project group of core researchers has some ten to fifteen members. The project group usually meets twice a year, running research projects. Some of them serve on the organisation’s board, which is led by Egil Bakka. Regular members are invited to conferences where projects and results are discussed and presented.

The project group has published several small research reports and three comprehensive works:

Gammaldans i Norden. Komparativ analyse av ein folkeleg dansegenre i utvalde nordiske lokalsamfunn

(1988, 302 pages; Round dances, nineteenth-century derived couple dances such as the waltz and polka in the Nordic countries). Comparative analysis of a traditional dance genre in selected local Nordic communities. It is based on some 285 filmed dances and interviews from comprehensive fieldwork in twelve communities across six countries.

Nordisk Folkedanstypologi. En systematisk katalog over publiserte nordiske folkedanser

(1997, 135 pages; Nordic folk-dance typology. A systematic catalogue of published Nordic folk dances). It offers overviews of and classifies 3267 dances.

Norden i Dans. Folk—Fag—Forskning

(2007, 712 pages; The North in Dance. People—Expertise—Research). This book surveys different groups of experts and their work on traditional dance/folk dance, including the topographers and early travellers; folklore and folklife collectors; theatre and ballet staff and those staging folk dance; the collectors, organisers, and teachers reviving folk dance; and specialised academic folk-dance researchers.

Finnish-Swedish folk dancers have performed the minuet for a hundred years at the aforementioned folk-dance reunions. One of the authors of this book, Gunnel Biskop, writes:

At the Nordic folk-dance event in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 1982, with six thousand five hundred participants from all the Nordic countries, a swish went through the audience when eight hundred Finnish-Swedish folk dancers began to perform their minuet; I was one of them. The minuet was that time from Kimito, and it can now be found on an over a hundred-year-old picture on the back cover of the book.

For a long time, it was generally believed that the minuet had been danced in the Nordic countries almost exclusively among the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. Thanks to this project, we can present that the minuet has been danced in many different environments and in folk traditions in Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway.

This book has a long prehistory for several of the authors. Gunnel Biskop has been conducting her own research work on the minuet since the early 1990s, writing a long series of articles on the minuet in the membership periodical of Finlands Svenska Folkdansring (the central organization for Swedish-speaking folk dancers in Finland), starting in 1993. She then decided to publish the results in Swedish for a Nordic audience in the book Menuetten—älsklingsdansen (2015) (The Minuet—The Loved Dance). Much of the material from that book has been translated into English and adapted in the current book.

Petri Hoppu defended his doctoral dissertation Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi. Menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (A dance of symbols and wordlessness. Minuet in Finland from the eighteenth century to the present) in 1999. He has written several articles on the minuet since 1993 and presented the dance at international conferences since 1997. Anders Chr. N. Christensen wrote two articles on the minuet in Denmark in 1993 and 1997.

Nff first engaged with the minuet in 2008, when the research group cooperated with French dance researchers about a seminar at the Centre national de la dance in Paris to present the Nordic minuet. In 2009, a similar seminar was held at Riverside, University of California, in cooperation with the teaching staff there, with Petri Hoppu and members of the Nff project group from Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). These seminars received support from Nordic Culture Point and NTNU. In 2013, the minuet was taken up as a research topic in Nff, and then, in 2014, the association decided to write a book in English with Petri Hoppu as the main editor. Since then, the project group has had the Minuet book as its main topic and has had about two meetings a year to develop the manuscript, with support from Nordic Culture Fund. Anne Fiskvik initiated a topically related research project at NTNU: Music, theatre and dance in the Norwegian public sphere 1770–1850, and Elizabeth Svarstad completed her PhD at the same university. She also presented elements from the Nff project at an international colloquium held at the Centre de musique baroque in Versailles December 2012 on behalf of Egil Bakka, Siri Mæland, and herself.

Thirty years have passed since some of the authors of this book wrote their first articles about the minuet, and Nff has worked with the minuet for some fifteen years. This work was done almost exclusively voluntarily, with the authors covering some costs themselves. During the last fifteen years, we have received support from Nordic Culture Fund, Nordic Culture Point, Letterstedtska föreningen, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), and the Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance. In addition, Danish folklore archives, University of Gothenburg, University of Copenhagen, Tampere University, Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, Norwegian Centre for Traditional Music and Dance, and Oulu University of Applied Sciences have given us space for meetings or paid for employees’ or members’ travel costs. We thank them all heartily for their support. All sections of the book have signed texts, and the authors are responsible for the content of each their contributions.

Göran Andersson, Sweden

Egil Bakka, Norway

Gunnel Biskop, Finland

Anna Björk, Sweden

Anders Chr. N. Christensen, Denmark

Anne Fiskvik, Norway

Petri Hoppu, Finland

Siri Mæland, Norway

Mats Nilsson, Sweden

Andrea Susanne Opielka, Faroe Islands

Elizabeth Svarstad, Norway

1. Introduction

Petri Hoppu

©2024 Petri Hoppu, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.01

The minuet is a Western European dance with particularly strong symbolic and cultural meanings. It is a couple dance in 3/4 time but, unlike other well-known couple dances like the polka or tango, partners do not touch each other for most of the dance. Instead, they move together, facing and passing each other, following predetermined figures, and using specific minuet steps. This book examines the minuet in the Nordic countries where it achieved popularity alongside many other European countries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Surprisingly, the tradition of dancing the minuet continues in some Nordic areas into the present day.1

The minuet is known in the Western world as a couple dance and music form that originated in the baroque era, specifically in the court of Louis XIV. In the popular imagination of today, it is a smooth and dignified dance, associated with wigs, large dresses, and tricorne hats. The purpose of this book is to show that this image of the minuet is too one-dimensional and that, especially in the Nordic countries, the minuet has appeared and still appears in many forms and contexts, as well as among many different groups of people.

What may be a surprise for some people, even those living in the Nordic countries, is that the minuet occupied a prominent position in the popular culture of the region in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, being danced by nobles and also by peasants. The dance, as part of the region’s social and cultural structures, impacted the development of society. From the late nineteenth century, the minuet ceased to form part of the active dance repertoire at social events in Europe, but exceptions to this exist in the Nordic countries: specific areas of Finland and Denmark continue to dance the minuet even today.

Over the centuries, discussions of the minuet have emphasized its formality and imagined rigidness. These qualities are suggested by metaphorical usage of the name ‘minuet’ but often also by theatrical staging of the dance. This book will counter such characterizations, contrasting the reality of dancing with such discourses. Whether as a court dance or a peasant dance, the minuet has enjoyable and lively dimensions. It can be noble and dignified but also cheerful, sensual, and intimate. This book is not the final truth about the minuet, but it reveals the minuet’s multiple dimensions and opens new Nordic and embodied perspectives on it.

The Intriguing Minuet

The minuet,

monsieur

, is the queen of dances, and the dance of queens, do you understand?

2

This quotation is taken from a fascinating 1882 short story by the French writer Guy de Maupassant in which an old man reminisces about his youth as a dancer of the minuet. The man comes to a park every day, wearing a costume and shoes fromtheancien régime (the social and political regime in place at the time of the French Revolution in 1789). He draws the attention of the narrator, who finally asks, ‘What was the minuet?’ This question revives the old man, and he replies with a lengthy description of the dance. The story culminates with the older man and a female companion performing the minuet as the narrator looks on in astonishment:

They advanced and retreated with childlike grimaces, smiling, swinging each other, bowing, skipping about like two automaton dolls moved by some old mechanical contrivance, somewhat damaged, but made by a clever workman according to the fashion of his time.

3

Few dances in the Western world have achieved the iconic status of the minuet. Since the seventeenth century, the minuet has been an important part of European culture, particularly in the discourses of dance and music. The subject continues to intrigue scholars and artists from the fields of performing arts and cultural studies. Similar attention is given to the waltz and tango, relating these couple dances to particular eras, symbolism, and behaviour. Yet, in many ways, the minuet stands on its own in European cultural history.

We, the authors of this book, share the curiosity of de Maupassant’s narrator regarding this dance tradition. We ask what was the minuet, but we also ask what is the minuet? Our study has involved reading about it, but also observing others as they danced it and dancing it ourselves, examining the minuet as a historical dance and also as a part of living tradition in some rural areas of the Nordic countries. We are fascinated by its originality, persistence, diversity, and its ability to survive throughout the centuries. These are the reasons we have compiled this book: an anthology of the Nordic minuet.

Dance and Metaphor

In a 1985 article about the minuet and its research, Julia Sutton wrote that:

[o]f all the dances popular from the accession of Louis XIV to the throne of France in 1661 until the French Revolution in 1789, the minuet is surely the most universally associated with that elegant period, not only because of its great popularity in its hey-day, but because it was the only baroque and rococo dance of that dancing time to be incorporated into the classical symphony and sonata, thereby remaining to the present day in the public ear (though not its eye), as a delightful reminder of an earlier time.

4

At the time Sutton was writing, many dance scholars and teachers had already begun investigating the minuet’s steps and figures as described by eighteenth-century printed and manuscript sources. From the early twentieth century, interpretations of the minuet have manifested in performances by companies specializing in historical dances. Sutton lamented in her article that the minuet’s origins were not clearly traced by such groups. She saw dance scholars’ different theories and hypotheses as contradictory, crying out for new scrutiny. Sutton observed that the minuet’s history after the French Revolution and its ‘folk’, or less aristocratic incarnations, was deserving of special attention.5

Intriguingly, Sutton called the minuet an ‘elegant phoenix’: a dance and musical form that had preserved its special symbolic status in Western culture over the centuries.6 This status has contributed to the considerable interest in the minuet from dance historians since the nineteenth century. Sherril Dodds, for example, noted that the minuet as a form of court dance has been highly valued by those interested in so-called historical dances—that is, high-society dances that were popular prior to the twentieth century.7 Such scholarship has a history of its own since the nineteenth century.8 Researchers of historical dances do have an established network of global scholarship, despite the often contemporary focus of the field of dance studies. Thus the minuet is part of a cultural dance phenomenon that has intrigued many scholars around the Western world.

One reason for ongoing interest in the minuet is that the dance has proved to be extremely persistent. The modern misconception is that the minuet disappeared from European courts and the standard repertoire of the nobility during the French Revolution in the late eighteenth century. Instead, it re-emerges like a phoenix over and over again in different contexts in Europe during the subsequent centuries. Indeed, the minuet reappears not only as a dance but also as a metaphor for something dignified, rigid, old-fashioned, or peculiar.

Fig. 1.1 The minuet. Pierre Rameau, Maître à danser (1725), engraving. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rameau_menuet.jpg, public domain.

As will be addressed in detail later in this book, the minuet continued to be performed throughout the nineteenth century. Surprisingly, it even appeared as part of the tradition of court balls within the German Empire at the end of that century. Minuets have also been spotted on Western stages, in theatres and films, most often to connote the atmosphere of theancien régime. More recently, the dance has appeared primarily in metaphorical usage in different contexts. A brief look at academic and literary texts published in the last fifty years reveals many instances in which the minuet is used in this figurative manner.

An American postmodern writer, John Hawkes, commenting on his erotic novel The Blood Oranges in 1972, wrote that:

It seems obvious that the great acts of the imagination are intimately related to the great acts of life—that history and the inner psychic history must dance their creepy minuet together if we are to save ourselves from total oblivion.

9

Hawkes seems to refer to the minuet as a metaphor for complicated and forced interaction that follows a specific structure to bring about clarity regarding human reality.

Similarly, in 1977, the American educational theorist Eva L. Baker contrasted the hustle (a fast-paced dance popular in the 1970s) and the minuet, using these as metaphors for evaluation:

As evaluations, the hustle and minuet differ along other continua, from energetic to passive, or exuberant to reserved. Notice, however, that these dances, as evaluation, both contribute at a marginal level to the serious pursuits of their times.

10

Baker views the minuet as an example of the worldview of a particular historical era, likening this to the changing dynamics of evaluation in education.

A Russian-born scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, Leon Aron, suggested in his 1995 article that relations between the USA and Russia/The Soviet Union could be characterized as an act of tango dancing but proposed that they could be improved by changing to something more akin to the minuet:

How about the minuet for a model: elaborate, graceful, slow, aloof, and cerebral? The partners spend a great deal of time away from each other, yet get together at regular intervals, give right hands to each other, and, upon turning a full circle, part again until the next occasion.

11

Aron regards the salient features of the minuet as positive and aspirational, emphasising its regularity and predictability. He considers that the nations’ relationship would benefit from a regular and stable structure, not the random and uncontrollable character of the tango.

A Finnish environmental psychologist, Liisa Horelli, used the minuet as a metaphor for a traditional and essentialist way of looking at gender in her article ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’ (1997). Although Horelli does not refer to the dance in her main text but only in the title, the message is clear. This article suggests that the titular minuet symbolizes binary gender roles which cannot be crossed. In contrast, progressive dance embraces gender-inclusive policy-making strategies, seen as an alternative to rigid gender roles.12

A final, and perhaps most surprising, example comes from an American professor of molecular and cellular biology: David D. Moore. He commented on his colleagues’ research paper and used the minuet as a metaphor for processes taking place on the metabolic level:

In the minuet, a popular court dance of the baroque era, couples exchange partners in recurring patterns. This elaborately choreographed exercise comes to mind when reading [this] paper [...]. In this study, the nuclear receptors [...] are two of the three stars in a metabolic minuet that promotes appropriate fat utilization.

13

Moore compares the precise and repetitive form of the minuet to the interaction between nuclear receptors. As a metaphor, the dance’s elegant choreography describes the pattern of the human metabolic system.

These examples indicate that the minuet is typically characterized by the attributes of calmness, ceremonialism, formality, and dignity. It is associated with highly formal behaviour, a quality that can be considered positive or negative depending on the context of the author reviewing the dance.

In all its different social contexts from courts to peasant villages, the minuet retains a human, corporeal dimension. It is not only a strictly formal dance, as its metaphorical usage suggests, but also an enjoyable and cheerful dance: an embodied experience. In the Nordic countries, where the minuet continues to be part of folk dancers’ repertoires, it is clear that the dance retains this expressive function. The minuet remains alive as both a narrative and dance practice.

Nordic Narratives and Embodiments

All of the continental Nordic countries have documented information about the minuet dating from the seventeenth century to the present day, encompassing all classes of society. In many ways, this is peculiar and unique. While the dance has not generally been a part of the active dance repertoire at European social events since the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, it has been performed in some areas of Finland and Denmark as late as in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This book argues that the minuet has had a remarkable position within dance culture in the Nordic countries, not only amongst the upper classes but also amongst the bourgeoisie and peasant population. The dance has been a part of the region’s social and cultural structures and has impacted the development of those structures.14 In the Nordic countries, the minuet is a cultural artefact that carries complex narratives and practices from various eras and areas.

It is no coincidence that various pieces of information about the minuet are found all over ‘Norden’ (the collective name given to Nordic countries in Scandinavian languages). Each Nordic country has a specific history of its own, but all share common social and cultural narratives and heritage. Norden, as defined by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén, is a collective performative space, resulting from repeated performances.15 The performances are points of departure for narratives and embodied experiences that connect people to the shared concept of Norden.

The Nordic collective space has been formed over the centuries as the Nordic countries have influenced each other. These relationships, however, have not always been harmonious. Historically, there have been strong tensions between the Nordic countries, especially the most powerful ones: Denmark and Sweden. Norway and Finland have been somewhat minor political players for many years. After becoming an independent kingdom, Norway formed a union with Denmark that lasted from the fourteenth century until 1814. Norway was then part of Sweden until 1905 when it became independent once again. Finland, by contrast, was a part of Sweden from the Middle Ages until 1809. At this point, Finland became an autonomous grand principality within the Russian Empire and finally gained independence in 1917.

Over time, as the borders and cultural hegemonies shifted within the region, the state power relations changed. The minuet has been a part of the cultural and political ebbs and flows reflecting the unique class relations and cultural models in Norden. However, the minuet is not the first or even the most conspicuous historical example of Nordic dance cultures. Narratives of other old Nordic couple dance forms are more prolific. Although these dances have different names, one name reoccurs in slightly different forms in all Nordic countries: pols (Norway), polsk (Denmark), or polska (Sweden and Finland). The pols(ka) and other related couple dances can be seen as a collective and generative phenomenon amongst Nordic folk dancers, and even as an ‘exportable’ dance form.16 The minuet is described in more specialised narratives, most often connected to specific rural areas in Denmark and Swedish-speaking Finland. However, the minuet also belongs to the contemporary Nordic collective performative space because its Danish, Finnish-Swedish, and Swedish forms are shared by folk-dance enthusiasts across the Nordic countries.

Narratives of dances cannot be separated from the practice of dancing. Where there is dancing, narratives and embodiments encounter each other, generating further practices and narratives. Minuet dancing in Norden has survived for centuries and its discursive and corporeal trajectories have shifted from the European upper classes to the local Nordic peasant communities. Since the twentieth century, Nordic folk-dance communities have danced the minuet both as a performance and participatory dance. Interest in Nordic folk dance even transcends the borders of the region. Multiple Nordic institutions and networks have been working to deepen their understanding of the dances and to build co-operation with enthusiasts in other cultures and countries as well.17

Our book is a witness of the transnationality of the minuet within the Nordic region. As members of a Nordic dance scholar community specializing in folk and historical dances, we take part in the narratives and embodiments of the minuet. We have written about the dance and we have danced its different forms, many of us for several decades. As an anthology of the minuet, the book is a meeting point for our experiences and knowledge of this fascinating dance. It is a testimony we want to share with the rest of the world. In this way, we share the curiosity and passion of de Maupassant about the dance and its dancers as expressed at the end of ‘Minuet’:

Are they dead? Are they wandering among modern streets like hopeless exiles? Are they dancing—grotesque spectres—a fantastic minuet in the moonlight, amid the cypresses of a cemetery, along the pathways bordered by graves?

Their memory haunts me, obsesses me, torments me, remains with me like a wound. Why? I do not know.

No doubt you think that very absurd?

18

Chapters

The chapters discuss different phenomena related to the minuet in the Nordic countries and elsewhere from the seventeenth century until the present. Each is divided into five parts covering documentation, research, structure, performances, and revitalisation related to the minuet, emphasising the Nordic forms and contexts of the dance. The authors draw from primary material in several languages and the chapters contain direct quotations as examples. These have been translated into English by the authors themselves unless stated otherwise.

Each author has conducted his or her research individually and thus, despite the fact that all have shared their results with one other, there is inevitably some duplication of sources and information between the chapters. Special attention should be paid to the extensive research of Dr Gunnel Biskop on the minuet, particularly as practised in Swedish-speaking Finland. The texts of Biskop in this book are largely based on chapters in her outstanding monograph Menuetten—älsklingsdansen [The Minuet—The Loved Dance] (2015).19 Several authors in this collection cite the monograph of Biskop and her other texts, since her work covers significant phenomena in the history of the minuet.

The texts in this book do not follow a homogenous approach. They were planned to serve different functions and they aim to target different audiences with their multi-dimensional portrayal of the Nordic minuet. There are chapters following the frames of conventional historiography and presenting excerpts from historical sources in a systematic order with comments and interpretations. These feed into general dance history methodologically and theoretically and provide access to new primary sources. There are also chapters presenting written descriptions of the dance in detail with comments and comparisons. These will be particularly relevant for practitioners working with the reconstruction of historical dances, as will the chapter presenting and applying a specific tool for movement analysis. Finally, some chapters reflect upon seeing the dance from contemporary and philosophical perspectives which aim to highlight the minuet’s position in the early twenty-first century. In this way, we combine the theoretical and methodological approaches with systematic and detailed presentations of historical material that, prior to the publication of this book, has only been available in Nordic languages. We hope this anthology will inspire others to research the minuet and its fascinating history further.

The chapters contain many dance names whose terminology is sometimes complicated. Whenever it is necessary, we explain them as they appear in the text. Most importantly, the term contradance (in French: contredanse) emerges repeatedly throughout the book. The contradances were inspired by English country dances and spread to most parts of Europe and the colonies from the decades around 1700 and onwards. Individual versions of the contradances were invented throughout the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Consequently, they became an important European dance paradigm. They are danced in sets of dancers, with typically four up to sixty individuals in each. The dancing consists of an ever-changing interaction between subgroups of those in the set. The set is usually composed of pairs but interaction can happen between two or more individual dancers, between two or more couples, between a group of ladies or between a group of men. This means that there will always be subgroups of changing size and with changing participants, moving together or in relation to each other within the set.

The first part of the book includes two chapters situating and defining the minuet as a form of dance and music. Egil Bakka and Andrea Susanne Opielka discuss different meanings and functions encompassed in the word ‘minuet’. Bakka examines the possible origin and early relations of the dance in a European context, the use of ‘minuet’ as a name of a dance, and how it correlates with movement structures. He also considers how research on the minuet in the European context compares to research on its Nordic practice. Opielka reviews literature related to European classical minuet music concerning the eighteenth century in particular.

The second part focuses on narratives about the minuet and its contexts in the Nordic countries. Anne Fiskvik sheds light on the activities of dance teachers in relation to the minuet. Then Anders Christensen and Gunnel Biskop look at the rural forms of the dance in Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark since the seventeenth century. Fiskvik, Christensen, and Biskop have spent many years investigating historical sources including letters, diaries, traveller descriptions, and documents from folklore archives. They have consulted this varied selection of sources to paint a picture of the minuet as a versatile phenomenon in Norden over the last three hundred years.

The third part of the book expands the investigation of historical narratives of the minuet in Norden. First, Elizabeth Svarstad and Petri Hoppu jointly discuss multiple examples of descriptions of the minuet in dance books published in the Nordic countries, starting with an overview of the different forms of the dance practised in Europe. Next, Bakka, Svarstad, and Fiskvik use similar documents to discuss the minuet in a European theatrical context. Christensen and Biskop then examine the folkloric documentation of the minuet in Denmark and Finland. The documentation began in the early twentieth century. Christensen investigates three regions in Denmark where the minuet remained important and discusses the kind of information folklorists and folk-dance enthusiasts recorded about the dance. Biskop describes the documentation process in Swedish-speaking areas in Finland, focusing on the extensive written records of Yngvar Heikel from the 1920s and 30s and on the film footage of Kim Hahnsson produced from the 1970s onward. Opielka, Hoppu, and Svarstad conclude this part of the book with discussions of the significance of minuet music in various Nordic contexts and source material of minuet melodies in multiple countries, with a particular emphasis on music books and manuscripts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Various forms and structures of the minuet are examined in detail in the fourth part of the book. The basic form of the early eighteenth-century court minuet, le menuet ordinaire, is detailed in numerous documents ranging from Nordic dancing masters’ manuals to folkloric recordings. These records also contain information about structural variations of the basic form. Biskop discusses the different forms, distribution, and contexts of the dance in the Nordic countries, especially in Finland and Denmark. Hoppu, Svarstad, and Christensen perform a comparative analysis of the steps and basic forms of the minuet, presenting examples that range from the minuet sourced in the eighteenth century to the minuet found in more recent Danish and Finnish folkloric sources. Finally, as a conclusion, Bakka, Svarstad, and Siri Mæland look critically at how minuet structures have been analysed and interpreted in European research. They present new ways of investigating dance structures, utilizing methods including Norwegian movement analysis, svikt analysis, and the principles of triangulation (the combination of various research methods in the study of the same phenomenon). They argue that both svikt analysis and triangulation contribute to a more versatile understanding of the structures of the minuet than results from earlier European dance research which has focused solely on court dances from restricted perspectives.

In the fifth part, the focus shifts to Nordic contexts of the minuet beginning in the early twentieth century. Biskop opens with various examples of the minuet as a living tradition in Swedish-speaking Finland. She describes, for instance, how Ostrobothnian soldiers danced the minuet at the Karelian front during the Second World War. She also examines the significance of the minuet as part of the Finnish-Swedish folk-dance movement today. In Sweden and Finnish-speaking Finland, although the minuet did not have any particular role in twentieth-century dance traditions, disparate groups of folk dancers resurrected the minuet during the latter part of the century in different ways. Anna Björk examines the phases of the reconstruction process and the position of the reconstructed minuet within the contemporary Swedish folk-dance field, while Hoppu attends to recently choreographed minuets practised by Finnish folk dancers. Finally, Göran Andersson and Svarstad discuss the role of the minuet among historical dance groups in Scandinavia and examine how these groups interpret centuries-old documents describing the minuet and how they use these documents as sources of new choreographies.

In the epilogue, Mats Nilsson and Hoppu review the various approaches and perspectives of the chapters and probe the multiple meanings found in the narratives and appearances of the minuet in the Nordic countries. They reflect upon their own embodied experiences and feelings of the dance, as well as its social and cultural contexts, summarising the story of the minuet thus far and anticipating its future.

References

Aron, Leon, ‘A Different Dance—from Tango to Minuet’, The National Interest, 39 (1995), 27–37

Aronsson, Peter and Lizette Gradén, ‘Introduction: Performing Nordic Heritage—Institutional Preservation and Popular Practices’, in Performing Nordic Heritage: Everyday Practices and Institutional Culture, ed. by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén (Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 1–26

Baker, Eva L., ‘The Dance of Evaluation: Hustle or Minuet’, Journal of Instructional Development, 1 (1977), 26–28

Biskop, Gunnel, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015)

Buckland, Theresa J., Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Dodds, Sherril, Dancing on the Canon: Embodiments of Value in Popular Dance (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Hawkes, John and Robert Scholes, ‘A Conversation on The Blood Oranges between John Hawkes and Robert Scholes’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 5 (1972), 197–207

Hoppu, Petri, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi—menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999)

Horelli, Liisa, ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’, Evaluation 3 (1997), 435–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909700300404

de Maupassant, Guy, ‘Minuet’, in Original Short Stories of Maupassant, 13 vols., trans. by Albert M. C. McMaster, A. E. Henderson, Mme. Quesada, et al. ([n. p.]: Floating Press, 2014), x, pp. 1533–38

Moore, David D., ‘A Metabolic Minuet’, Nature, 502 (2013), 454–55

Nilsson, Mats, ’From Local to Global: Reflections on Dance Dissemination and Migration within Polska and Lindy Hop Communities’, Dance Research Journal, 52.1 (2020), 33–44

Sutton, Julia, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52

Vedel, Karen and Petri Hoppu, ’North in Motion’, in Nordic Dance Spaces. Practicing and Imagining a Region, ed. by Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 1–17

1 The Nordic countries referred to in this book consist mainly of the continental part of the Nordic region: the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, as well as the Republic of Finland, including the autonomous region of Åland. Although the Atlantic islands, the Republic of Iceland, and the Danish autonomous regions of the Faroe Islands and Greenland belong to a Nordic political and historical entity, the minuet has not played any significant role in their cultural histories, and, therefore, these are little discussed.

2 Guy de Maupassant, ‘Minuet’, in Original Short Stories of Maupassant, 13 vols., trans. by Albert M. C. McMaster, A. E. Henderson, Mme. Quesada and others ([n. p.]: Floating Press, 2014), pp. 1533–38 (p. 1537).

3 Maupassant, pp. 1537–38.

4 Julia Sutton, ‘The Minuet: An Elegant Phoenix’, Dance Chronicle, 8 (1985), 119–52 (p. 119).

5 Ibid., p. 120.

6 Ibid., p. 142.

7 Sherril Dodds, Dancing on the Canon: Embodiments of Value in Popular Dance (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

8 Theresa J. Buckland, Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

9 John Hawkes and Robert Scholes, ‘A Conversation on The Blood Oranges between John Hawkes and Robert Scholes’, NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 5 (1972), 197–207 (p. 205).

10 Eva L. Baker, ‘The Dance of Evaluation: Hustle or Minuet’, Journal of Instructional Development, 1 (1977), 26–28 (p. 26).

11 Leon Aron, ‘A Different Dance—from Tango to Minuet’, The National Interest, 39 (1995), 27–37 (pp. 36–37).

12 Liisa Horelli, ‘Engendering Evaluation of European Regional Development: Shifting from a Minuet to Progressive Dance!’, Evaluation,3 (1997), 435–50, https://doi.org/10.1177/135638909700300404 (p. 435).

13 David D. Moore, ‘A Metabolic Minuet’, Nature, 502 (2013), 454–55 (p. 454).

14 Petri Hoppu, Symbolien ja sanattomuuden tanssi—menuetti Suomessa 1700-luvulta nykyaikaan (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1999).

15 Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén, ‘Introduction: Performing Nordic Heritage—Institutional Preservation and Popular Practices’, in Performing Nordic Heritage: Everyday Practices and Institutional Culture, ed. by Peter Aronsson and Lizette Gradén (Burlington: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 1–26.

16 Mats Nilsson, ‘From Local to Global: Reflections on Dance Dissemination and Migration within Polska and Lindy Hop Communities’, Dance Research Journal, 52.1 (2020), 33–44 (pp. 38–40). In Norway, these couple dances are called ‘bygdedanser’, a term which includes pols as well as springar, gangar, and halling.

17 Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu, ‘North in Motion’, in Nordic Dance Spaces. Practicing and Imagining a Region, eds Karen Vedel and Petri Hoppu (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 1–17.

18 Maupassant, p. 1538.

19 Gunnel Biskop, Menuetten—älsklingsdansen. Om menuetten i Norden—särskilt i Finlands svenskbygder—under trehundrafemtio år (Helsingfors: Finlands Svenska Folkdansring, 2015) [The Minuet—The Beloved Dance: On the Minuet in the Nordic Region—Especially in the Swedish-Speaking Area of Finland in the last Three Hundred Fifty Years].

PART I

DEFINING AND SITUATING THE MINUET IN HISTORY AND RESEARCH

The first part of this book defines and situates the minuet as a dance and a musical form. Its chapters discuss the role of the minuet in European society and culture since the seventeenth century as well as its research and historiography.

2. Situating the Minuet

Egil Bakka

©2024 Egil Bakka, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0314.02

The starting point for my investigation is the name of the dance and whether it corresponds to one or more basic movement structures. This chapter then examines the distribution of the dance in time and space, comparing contentious ideas about its origins and ascertaining how political and social references have shaped interpretations of the dance. For these purposes, it is necessary to establish the minuet in its European historical context, including the European research landscape, despite the book’s concentration on the forms and roles of the dance in the Nordic countries.

Name and Distribution

The name ‘minuet’ occurs in various forms in different languages. Menuet (French) is the point of departure; slight variations of this word are found in many European languages: the German Menuett(e), the Swedish and Norwegian menuett, the Danish menuet, the Spanish minué, the Italian minuetto, and the Russian менуэт. Additionally, there are dialect(al) versions of the word, such as the Danish monnevet, møllevit, mollevit; the Swedish minuett, möllevitt; Finnish minetti, minuutti, minuee (Finnish); and the Norwegian mellevit.1 Some forms refer to the mix of the minuet and other dances, such as the Spanish minué afandango, a minuet partly composed of allemande.2 We also find the term ‘Volks-Menuet’ [folk minuet] which, at least in the case referred to, is a comparison between the style of the Russian national dance to that of the French court minuet. It is not proposing that the minuet had become a folk dance in Russia.3 In the same spirit, a French source characterises the Farandole as ‘this popular minuet’, not to hint that the dances are related but rather to imply that the two dances are similar in function and status.4

Surprisingly, the minuet does not seem to have been fully taken up into folk culture anywhere in Europe except in the Nordic countries, where it has survived as continued practice. It has not been possible to find definitive sources that permit any other interpretation. Proving a negative is difficult, but the following examples do suggest that the minuet was not part of folk culture in the rest of Europe.

Richard Wolfram, an Austrian dance ethnologist, for instance, was one of the most knowledgeable researchers of Austrian folk dance, and he could find little evidence of the minuet in this context. Comparing the history of Austrian and northern European folk dance, Wolfram concluded:

The ‘folk’ do take over [material from the upper classes], but not without making selections. In this way, the minuet remained almost without impact on Austrian folk dance even if the educated classes mastered it for a long period. The minuet was only played as table music at weddings and similar events in rural environments. Its courtly form could not find any danced expression here.

5

A similar idea is offered in a long and well-informed article from 1865 that criticises staging practices of Mozart opera Don Juan. Discussing the historicity of staging practices, its anonymous author asks why Mozart and his libretto writer use the minuet in an opera purportedly set in Spain, since the story involves a peasant couple. The implication is that Spanish peasants do not dance the minuet. Although the statement is quite general and absolute, it points in the same direction as the previous quotation.6

Video 2.1 The minuet in a 2001 Zurich production of W. A. Mozart, Don Giovanni, complete opera with English subtitles. Uploaded by Pluterro, 5 November 2017. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/2a74d4a1. See timecode 01:26:59.

The German author and philosopher Karl Heinrich Heydenreich (1764–1801) wrote the article ‘Über Tanz und Bälle’ [Dance and Balls] in 1798. In it, he portrays the minuet as the most valuable dance at upper-class balls and states bluntly that the dances of the lower classes are just a raw mixture of hopping, jumping and circling. Heydenreich does not suggest that the lower classes copy the upper classes.7

From these sources, we conclude, like the Swedish musicologist Jan Ling who writes extensively about dance in his European History of Folk Music (1997), that there is little evidence of a folk minuet outside of the Nordic countries.8 It is nevertheless important to review some folk dances outside of the Nordic countries because some of these are called the minuet and we need to check to what degree they are similar to the main forms of the minuet. Julia Sutton refers to a German minuet: the ‘Treskowitzer Menuett’.9 This is danced to music in 3/4 time like the minuet in which we are interested—but has a square formation, walking steps, and ends with a waltz. As the following video recording from the Dancilla website shows, this ‘Treskowitzer Menuett’ does not share the typical movement patterns of the minuet that will be presented in detail in later chapters.10

Video 2.2 ‘The Treskowitzer Menuett’, Dancilla website (2020), https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/ead1d1a8. See both videos on this page.

Dancilla includes other videos showing dances that are referred to as minuets but also do not share its characteristics. Some seem to be folk-dance style choreographies set to pieces of classical music.

In the Czech Republic, a folk dance called Minet has been assumed to be a minuet version due to its name. A publication entitled Lidové Tance z Čech, Moravy a Slezska [Folk Dances from Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia] is an ambitious series of ten videos, each accompanied by a separate booklet. The series presents the folk dances of the Czech Republic danced by folk-dance groups all over the county.11 In this collection, we also find several names that are similar to the minuet:

Minet—corava c Hlineca Vysokomytska a Crudimska, vol. III, piece E 11 3.

This is a couple dance danced on a circular path to waltz-like music.

Minet ze Stráznice u Melnica, vol. IV, piece D 11.

Minet z C̆áslavska, vol. IV, piece D 17.

The D 11 minet opens with men and women facing each other in two lines, which is one of the most popular formations in minuet, but then continues as a waltz couple dance. The D 17 is also more of a waltz couple dance.

Menuetto (minet) z zapadni Moravi a cheskomoravskeho, vol. V.

This dance, with the name Menuetto, has a line formation and uses some steps on the place that vaguely resemble features of the minuet.

The Minet dance form, which is the most similar to what we would now define as ‘the minuet’, was collected 1912–13 by Fritz Kubiena in Kuhländchen, a region in the eastern part of the present Czech Republic that was inhabited at the time by a German population. Kubiena gives a precise description of the dance and accompanying music in the folk-dance collection he published in 1920.12 As can be seen in the following video, the dance does not have minuet steps or a full minuet form, but similarities in music and style suggest that the Minet may imitate minuet patterns:

Video 2.3 Das Kuhländler Mineth. Folk dancers safeguarding heritage from Kuhländchen perform eleven dances. Uploaded by Wir Sudetendeutschen, 30 April 2020. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d7079ef1. See the Mineth at timecode 8:24.

Compared to the minuet as danced by the French court, descriptions of the minuet given by European dancing masters, and those practised by Nordic folk dancers, the Czech Minet(h) dances seen above are not recognisable as minuets. Some seem to be different dances altogether. One or two have features that might have been inspired by the minuet but not much more.

Moving away from European examples, dance theorists Russel and Bourassa claim that, to this day, a form of the minuet is danced in Haiti. This dance, called in Creole the menwat, is as part of a sequence of dances that echoes the order of eighteenth-century balls.13

Fig. 2.1 George Henriot’s watercolour Minuets of the Canadians (1807) seems to confirm that the minuet was danced even in Canada. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Minuets_of_the_Canadians_-_TPL.jpg, public domain.

A Definition of the Minuet as Movement and Music Patterns

How can the minuet be characterised as a form? Do the movement patterns labelled ‘minuet’ in its different linguistic variations have a cohesiveness, and can it be defined clearly and consistently? In many discourses, the minuet is a dance. This is logical in the context of traditional social dancing and for the minuet’s realisation within a single community. The minuet functions as one dance in the local repertoire during a specific period, whether this is the menuet ordinaire performed in French court circles or the menuet[t] danced in Nordic urban and rural communities, particularly in Denmark and Finland. In the latter case, there were regional variations and the dance form changed over time as is usual for any dance. Still, the movement patterns and the music of these Nordic minuet forms show a surprisingly strong unity. The choreographed versions of the minuet, particularly in French court circles, do not follow this model. If we want to identify the minuet movements shared by all variations carrying the name, another concept or dance paradigm might help.

A dance paradigm is a set of fundamental and constitutive conventions for how a specific form of dancing is organised. It is a long-lasting and widespread cluster of conventions which provides the basis for a particular kind of dancing. Some criteria for identifying a dance paradigm could be a new set of conventions for the design and organisation of dancing that is so radically different from what is already in use, that it is perceived as something completely new in the place where it settles.

14

A dance paradigm is stable enough to remain in use over a long time.

Its conventions are inspirational and fruitful enough to give rise to an extensive dance practice.

A group of characteristics can be used to define which dances belong to the paradigm but no single characteristic is necessary or sufficient to include all dances of the paradigm. This is the principle of polythetic classification.15 An assessment must be made in each case of a dance realisation to determine if it belongs to a specific paradigm. Not all dance forms do.16

To ascertain what is typical of a minuet, it is essential to look at the movement patterns and not base any judgement strictly on the name. The main reason for this is that the choreographed forms that were used in the French court tradition were unlikely to appear unchanged as social dances in subsequent decades. For many later choreographers, it was more important to break the conventional framework in one way or another than to maintain a connection to the older menuet ordinare. Therefore, these choreographies must be assessed by other criteria. We propose defining the minuet as a social dance based on the following conventions:

the dance can be performed by one couple

it may group two couples together

it may group many couples in a line of men and a line of women facing each other

the dance does not move far away from the place it started, or, at least, it returns to the starting point

the music is in 3/4 time

the step pattern spans two bars

the partners move both toward and away from each other

the partners change places and change back again

the partners can use one same-hand fastening

17

Some Points of View on Historiography

Histories of dance in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries rely heavily on excerpts from a large variety of written sources that describe dancing or dances at that time. Such source material is not easy to find. If the scholar cannot access specialised archives, he or she must depend on materials located by earlier researchers and even adopt their interpretations. These repetitions tend to lend the interpretations an air of reliability that is seldom questioned. Without revisiting primary sources, or not doing so in a systematic way, dance historians have tended to present fragmented narratives. Dance groups interested in historical re-enactments, for example, have used the dance notations and descriptions from earlier centuries’ dancing masters. However, this work rarely displays the rigour of advanced research. The Dean of Research in French Dance Ethnology, Jean-Michel Guilcher, is an exception. He wrote an exemplary study of the eighteenth-century French contredanse, combining detailed analysis of its forms with an impressive contextualisation of the social and political life of the era.18

We argue here that this kind of critical approach is needed to achieve progress in dance history. Another significant point is that dance history has tended to be written about one genre at a time. Some historians specialise in the history of theatrical dance; others write about the history of the social dances of the upper class. Relatively few write about the history of folk dances or the dancing practised by the lower classes. Yet these different classes and different kinds of dancing existed simultaneously throughout history. This book will reveal that although there were socioeconomic divisions and specialisms, people of various groups were part of the same world and did interact. We argue that dance history should take such interaction into account to create fuller pictures of historical periods.

Fig. 2.2 Marten van Cleve, A village celebrating the kermesse of Saint Sebastian in the lower right corner there are groups of upper-class people celebrating side to side with the peasants (between 1547 and 1581), oil on panel. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marten_van_Cleve_-_A_village_celebrating_the_kermesse_of_Saint_Sebastian,_with_an_outdoor_wedding_feast_with_guests_bringing_gifts.jpg, public domain.

Finally, it is crucial to understand dancing and dances as belonging to paradigms, each of which relies on specific organizational conventions. Seeing dances as parts of certain paradigms yields a safer hypothesis about their genesis and development than drawing comparisons between isolated traits of dances not studied in context. For instance, a specific way of holding hands needs to be recognised as part of a paradigm. One such similar feature between two individual dances does not tell us much about how or whether they are related.

Dances are movement designs, which are often based on stunning relationships between strict, long-lasting, deep structures that remain stable through time and space. They usually appear with superficial variations in what are often called dance dialects but maintain the basic deep structure. Dance history needs to be understood within the context of social class, social functions, music, dress, gender roles and conventions; however, dance history also needs to include the history of the dance. The movement structures are the substance of the dance and the dances are not only inventions that reflect a cultural moment but also long-lasting patterns that connect and explain the present through the past. The following is an attempt to view the minuet from the latter perspective, where dance form and the context of dancing are merged in the analytical process. This is also the methodological point of departure for the following brief discussion about the genesis of the minuet.

The Genesis of the Minuet

Very little evidence describing the origins of the minuet is available. However, several sources do cite a score from 1664 as the first appearance of the minuet. A document containing information about a Comédie-ballet that premiered in that year mentions the dance. Later, the advisor of Louis XIV Michel de Pure (1620–80), published a book on dance and court ballets in 1668 confirming that the menuet was relatively new at that time: ‘As for the quite new inventions, these Bourrées, these Minuets, they are only disguised repetitions of dancing master’s toys and honest and spiritual pranks to catch fools who have the means to pay’.19

A brief contention about ‘where the minuet came from’ is repeated in almost all, even the shortest, pieces written about the dance. The core of the argument is that the minuet comes from Poitou and further that it is a derivation or adaptation of one of the region’s traditional dances: the Branle de Poitou. One such text described the minuet, for instance, as an

Old French dance, triple time, which appears in the seventeenth century and seems to be derived from of a ‘

branle

to lead’

Poitevin

. [The French composer Jean-Henry] D’Anglebert [1629–1691] named actually [one of his works] the

Menuet of Poitou

in his harpsichord pieces, which offer a primitive type thereof.

20

There is also a Branle de Poitou described in the famous musical study Orchesographie by Thoinot Arbeau (1589).21 The French philosopher and composer Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) repeated the idea of Poitou as the origin of the minuet, crediting the French cleric Sebastian de Brossard (1655–1730) with the notion but disagreeing with him about the character of the minuet.22Brossard, however, did not refer to the Branle at all, only to Poitou; he also described another dance, the Passe-pied, as a ‘rapid minuet’ and yet another, the Sarabande, as a ‘severe and slow minuet’.23 Did Brossard consider the minuet a general term for any type of couple dance?

Another more probable explanation for the references of Rousseau and Brossard to the ancient region of Poitou is that in the early seventeenth century, Poitou was a centre for the making of woodwind instruments, and Hautbois de Poitou was the name of a specific oboe-like instrument.24 Throughout the seventeenth century, the French court had a musical ensemble by the name ‘Hautbois et Musettes de Poitou’. The ensemble probably derived its name from these instruments since it is not likely that it was populated with musicians from Poitou, over this long period or mainly played music from the region. No other regions are mentioned in this context, yet the name Poitou seems to have had a strong presence at court.25

Fig. 2.3 Frontispiece and title page from Moliere, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1688). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BourgeoisGentilhomme1688.jpg, public domain.

Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, a comédie-ballet first performed on 14 October 1670 before the court of Louis XIV, bore out this suggestion containing the following stage directions: ‘Six other French come after, dressed gallantly a la Poitevine accompanied by eight flutes and hautbois and dance minuets’.26 Its music was composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully and its choreography was made by Pierre Beauchamp. Therefore, we can surmise that Beauchamp may have introduced the minuet at court for the first time through this work but the name minuet and some musical and choreographical elements could be older. References to Poitou, then, probably appear in the ballet because within this performance, six of the court dancers are dressed as people from Poitou, perhaps to match the name of the music ensemble at the court.

Video 2.4 Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully from Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, ‘Menuet pour faire danser Monsieur Jourdain’ [Menuet to make Monsieur Jourdain dance]. Uploaded by Vlavv, 24 December 2010. YouTube, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4d73077b

Reviewing mentions of the French branles in written sources and popular tradition may contribute to our understanding of the genesis of the minuet. There are many tunes and many versions of the dancebranle, but it is beyond our scope here to give more than a few examples. Nevertheless, one might suspect that the meter and other characteristics of the music, rather than the dance pattern, is the basis of the claim that links the branle and the minuet. Jean Michel Guilcher found similarities between Arbeau’s sixteenth-century branle types and the material about the contredanse he collected in the mid-twentieth century. He does not, however, suggest any connection to the minuet when he mentions the pattern of the Branle de Poitou.27