1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

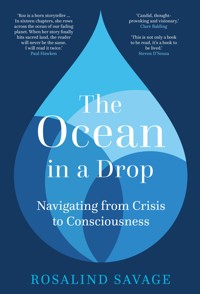

- Herausgeber: Flint

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The bad news is that our civilisation is collapsing. The good news is that you are already helping create a new and better one. The Ocean in a Drop follows the quest of Roz Savage, a frustrated environmentalist and ocean adventurer, to find out why her own endeavours and the environmental movement more generally have failed to achieve change of the necessary scope, scale and speed. Her journey takes her from the environment through economics and politics into patriarchy and a global culture of domination – the domination of rich over poor, strong over weak, humanity over nature. She examines the tragic psychological flaws in the way we think, and the apparent inevitability of civilisational collapse, and deduces that our best hope is to transcend the current trap of runaway materialism. But how? Exploring cutting-edge theories on the nature of reality and the relationship between matter and consciousness, she peels back the veils of our shared delusions to arrive at a new narrative about what it means to be human in the twenty-first century. She paints a bold, exciting vision of a future in which people and planet thrive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise for The Ocean in a Drop

‘The earth is ailing. What is the diagnosis, and where is the cure? Roz Savage is dauntless in her quest for answers. Strap in and join her for a riveting ride on The Ocean in a Drop. A world-class athlete, she rows the Pacific alone, with an unblinking eye on the symptoms of the patient. An Enlightenment intellectual, she pursues a diagnosis based on reason, and on sciences varying from politics and economics to cognitive neuroscience and evolutionary biology, all the while knowing that if reason is consistent then it must be incomplete. A compassionate human, she inspires us to embrace our innate intelligence that transcends the limits of reason, and follow its guidance to unexpected remedies. If we heed her prescription, our prognosis is bright.’

Donald Hoffman, author of The Case Against Reality

‘This is a book by, of and for this moment. A paean to human resilience and courage, it shows what happens when we cast off the shackles of our normative behaviours and discover who we really are, attend to our inner voices of integrity and authenticity and stretch ourselves to the edges of our being … Roz Savage paves the way towards a different future with the blistering light of deep personal exploration, and the authentic voices of some of our planet’s deepest thinkers. This book is essential reading for anyone who wants to see the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible come into being.’

Manda Scott, author of the Boudica: Dreaming series

‘This well-researched and readable book may well give encouragement to readers for a change in our conscious lifestyle. The author points out that our civilisation is sick. To effect a cure, it is helpful to examine the symptoms and underlying causes. The good news is that we are nonetheless fundamentally healthy. Roz Savage sets out not only to lucidly present the ills that beset our world – environmental, economic, political, social and so on, but she uncovers the psychological, neurological and spiritual causes of our problems. Based on this analysis with characteristic intrepidity she presents her vision for a future redemption when humanity will finally turn the corner and regain its healthy values of basic sanity. Despite humanity’s pathetic track record to date, Ms Savage dares to nurture sanguine expectations of our ultimate reform.’

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, Buddhist nun

‘Anyone who rows solo across three oceans deserves our undiluted attention. Beyond that, this magical book distils Roz Savage’s hard-won wisdom at a time when we all must learn to see ourselves and our worlds from outside. The Ocean in a Drop alternates between the alarming, the challenging and the uplifting. Formidable forces are now at work, for better or worse, and, as the book concludes, “miracles might just happen”.’

John Elkington, founder and chief pollinator at Volans, and author of Green Swans

‘The Ocean in a Drop vividly shares a wonderfully authentic and transformational journey, of both inner and outer discovery that is radically relevant for all of us for how we see ourselves and the world at this critical moment of choice. While its clear-eyed and yet compassionate appraisal of how our current systems and behaviours, based on separation and dominance, have brought us to an existential crisis, its greatest gift is to reveal and empower the potency and potential, through our conscious evolution and a new and unitive narrative, of how our existential emergency can be transformed to the emergence of a world that works for the good of the whole.’

Dr Jude Currivan, cosmologist, author of The Cosmic Hologram and The Story of Gaia and co-founder of Whole World-View

‘Great wisdom can be found in the convergence of science and spirituality. Roz takes this wisdom and applies it to our seemingly intractable global challenges. She paints a picture of how we can use our attention, intention, and innate gifts to achieve an important paradigm shift that would propel us towards a beautiful vision of a thriving future.’

Chade-Meng Tan, author of Search Inside Yourself and Joy on Demand

‘A thoroughly researched document that gives the reader a clearer understanding of why the world is as it is – the economics, social, psychological and cultural forces at play. Roz presents a vision of how the future can be better while inspiring and encouraging us that we have a purpose, a role to play and the power to make a positive difference. This book is well timed and needed, a life preserver in our chaotic times.’

Will Steger, educator and explorer

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material. In the event of any omission, please contact [email protected].

Excerpts reprinted with permission of the publisher, from Confessions of an Economic Hit Man © 2004 by John Perkins, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco, CA. All rights reserved.

Excerpts reprinted with permission of the publisher, from Rethinking Money: How New Currencies Turn Scarcity into Prosperity © 2013 by Bernard Lietaer and Jacqui Dunne, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco, CA. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from If Women Rose Rooted by Sharon Blackie, published by September Publishing, 2016. Reprinted with permission.

Excerpts from Edgar Cayce Readings © 1971, 1993–2007, The Edgar Cayce Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Excerpt reprinted with permission of the publisher, from Synchronicity: The Inner Path of Leadership © 2011 by Joseph Jaworski, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., San Francisco, CA. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Why Materialism Is Baloney by Bernardo Kastrup, published in 2014 by Iff Books, an imprint of John Hunt Publishing, www.johnhuntpublishing.com.

First published 2022

FLINT is an imprint of The History Press97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,Gloucestershire, GL50 3QBwww.flintbooks.co.uk

© Rosalind Savage, 2022

The right of Rosalind Savage to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9233 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Prologue

PART ONE: THE BAD NEWS

Chapter 1: Environment

Chapter 2: Economics

Chapter 3: Politics

Chapter 4: Power

PART TWO: THE EVEN WORSE NEWS

Chapter 5: Psychology

Chapter 6: Hemispheres

Chapter 7: Systems

Chapter 8: Collapse

PART THREE: ESCAPE

Chapter 9: Paradigms

Chapter 10: Chaos

Chapter 11: Reality

Chapter 12: Ego

PART FOUR: THE NEW PARADIGM

Chapter 13: Preamble

Chapter 14: Principles

Chapter 15: Practicalities

Chapter 16: Present

Epilogue

To Ponder

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Notes

Prologue

I was awoken by my bed suddenly lurching several feet to the side and tilting sixty degrees. I groaned as I returned from a pleasant dream about a buffet table creaking under the weight of all my favourite foods and remembered where I was: alone on a 23-foot rowboat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Deeply resenting the wave that had smashed into the side of my boat and wrenched me away from the smorgasbord of delights, I rolled over on my narrow bunk and closed my eyes, trying to return to blissful unconsciousness. But reality had smashed in as brutally as the wave, and sleep was gone.

I sighed and turned on the GPS to see where I was. During the hour I’d been asleep, the winds and currents had carried me about a mile towards my destination. One mile out of a total of 3,000, from one side of the Atlantic to the other. Not bad, but if I’d been rowing instead of dozing I would have covered two or maybe even three miles. But the distance ahead seemed so vast, I could make up for this wasted hour later … Couldn’t I?

I paused. An uncomfortable truth was niggling at the edge of my awareness. I gave it a moment to reveal itself.

This wasn’t really about the difference between one mile, or two or three. This was about who I was and how I wanted to show up for this enormous challenge I’d set myself. Did I want to be the kind of person who slacked off and skipped rowing shifts when I felt tired, overwhelmed or in pain? Or did I want to be the kind of person who committed fully, did my best and stuck to my rowing schedule with discipline and determination? With every choice I made – whether to row or not to row – I wasn’t just crossing an ocean. I was creating a story about myself. I would become the sum total of the seemingly tiny choices I made every day, each one inconsequential in itself, but adding up to a story of what it means to be me.

Who am I?

Who do I want to become?

How do I show up when nobody’s looking?

I knew what story I wanted. It wasn’t yet true, but this was in my hands. I could make it come true by making different choices – choices that might seem harder at the time, but would bring ease and peace at the end of each day when I could log the miles covered and know I’d done all I could to get closer to my vision – a vision not just of reaching the other side of the ocean, but of crafting a new identity for myself, no longer a burned-out management consultant, but an adventurer and explorer of the oceans, of the world.

I shook myself out of my reverie, pulled on my rowing gloves and sunhat, grabbed my seat pad, and headed out of the cabin to the rowing seat to continue creating my new story, one oarstroke at a time.

As we approach the quarter-way point of the twenty-first century, humanity is being challenged to create a new story about who we are. When we contemplate the myriad wrongs of the world – such as inequality, racism, social injustice, climate change, plastic pollution, ocean acidification, habitat destruction, poverty, conflict, corruption, authoritarianism, polarisation and discrimination – we might feel despair and desperation. Many of us have bought into a story of separation, isolation and existential fear that paradoxically creates the very situations we’re trying to avoid. While we choose to believe that each of us is just an inconsequential drop in the ocean, we do a great disservice to ourselves, our species and our planet. It might be a comforting story, because identifying as a powerless droplet gets us off the hook of doing anything about global challenges that can, admittedly, seem overwhelming. But it’s not a true story, and it’s not an empowering one.

In the midst of ongoing turmoil, and having weathered many storms of grief and despondency, I have found hope. But as the environmental entrepreneur Paul Hawken said on my podcast, hope can be the pretty mask of fear, so we need the right kind of hope: a trenchant tenacity and beautiful audacity; a surrender to what is, while also holding fast to a vision of what can be; and the deep knowing that we have the power, energy and agency to make a difference through the choices we make. It’s this kind of hope I offer and that this book is about: a hope grounded in a new story about what it means to be human at this critical juncture in our species’ history; a story that gives us back our courage, dignity and power; a story that can lead us into a new paradigm of unity, connection and love.

This book is about the course I’ve navigated over the last twenty years to try and find that better story – my questions, frustrations, inspirations and occasional quantum leaps in understanding. Like many adventurers, I began by studying the paths forged by others – those who have explored questions around the environment, economics and the ways in which humans have chosen to live, individually and collectively. I’ve combined and recombined and riffed on these concepts to arrive at a plausible explanation of where we are now and to create a vision of a possible future. This book is the account of my personal voyage of discovery, my adventures and misadventures in envisioning a better world.

As you will see, this book is ambitious in its scope and bold in its imagination. I throw a lot of ideological and metaphysical spaghetti at the wall, and some of it will stick for you, some of it almost certainly won’t. To mix my metaphors, I just ask that you don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater. Even if you violently disagree with some of the ideas presented here, please persevere with an open mind. I intend to start a conversation, not to have the final word. I cherry-pick from the books I read, choosing the juicy fruits, adopting and adapting them to my own needs, and discarding the rest. I trust you to do the same.

For sure, I’m not claiming to be the hero arriving with the eleventh-hour solution to all our problems. I’m not even saying we’re going to make it through the multi-tentacled crises currently engulfing the world. It’s up to all of us to forge our future together. Crisis is an opportunity for transformation. Good things are possible, and together we can make them probable. Together, we can create a clear vision of the future we want and hold that vision as our north star as we navigate the uncharted, turbulent waters of the future.

Chapter 1

Environment

‘There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with people. Given a story to enact that puts them in accord with the world, they will live in accord with the world. But given a story to enact that puts them at odds with the world, as yours does, they will live at odds with the world. Given a story to enact in which they are the lords of the world, they will act like lords of the world. And, given a story to enact in which the world is a foe to be conquered, they will conquer it like a foe, and one day, inevitably, their foe will lie bleeding to death at their feet, as the world is now.’1

Daniel Quinn

A hailstorm hit just as we left our campsite, high in the Andes above Cusco, the hailstones pinging painfully off ears, noses and hands. The first section of our trek was mostly uphill, a stiff climb, but the old woman leading our procession strode on undaunted. The pace was being set by someone twice my age and pride forced me to keep up.

As the hailstorm abated, we were left with a dramatic skyscape of dark clouds and bright sunshine, the sun’s rays picking out distant mountains in a variety of colours and textures – red dust, green grass, white snow. My self-appointed guide, Abel, had promised me that this was a camino bonito – a much prettier walk than the dusty path that had led us to the sacred mountain of Ausangate several days before – and he was right. Our little troupe of pilgrims filed across the high altiplano, headed by a brother carrying the flag of the Inca, while we dutifully followed the fluttering rainbow.

When we reached a high pass, Abel pointed out a plume of smoke rising from a distant valley, signalling the village where we would rest for a few hours. The trail led straight to it, but to our left I could see a herd of alpacas and a flat plain of serpentine pools that beckoned to the photographer in me. I told the others I would catch up with them later and headed off alone to spend a pleasant hour taking pictures, watching the late afternoon sun raking across the landscape, backlighting the soft fur of the alpacas into golden halos. The solitude and peace of the mountains were a welcome respite from the noise and confusion of the last few days, when 30,000 pilgrims had crowded into a high hanging valley for the festival of Qoyllur Rit’i and had danced morning, noon and night – possibly out of practicality as much as piety, as it was icy cold up by the glacier and dancing was the best way to fend off hypothermia.

Feeling calm, restored and reconnected with nature, I strode purposefully down into the village, following a cascading stream through a deep gully, and rejoined the others. Spirits were high when I arrived at the pilgrims’ camp. A couple of lively ukukus (men dressed as bears, the designated pranksters of the pilgrimage) had run up the mountainside, and everybody else was watching them, shouting encouragement and laughing at their antics as they slithered and tumbled their way back down the slope.

We had only about four hours to rest before we would be back on the trail again. Abel had explained to me how, before leaving Ausangate, he would go to a rock near the chapel where an angel and a devil – not real ones, I later established, but humans in costume – would tell him what time we were to start the final leg of our pilgrimage. Our appointed hour was ten o’clock that night.

I made myself comfortable in the lee of a drystone wall, setting out my camping mat and sleeping bag on top of a plastic poncho. I pulled tight the drawstring of my sleeping bag, leaving only a small air hole, and snuggled in, feeling snug and smug in my cosy cocoon, anticipating a restful sleep.

No sooner had I settled down than the band struck up at top volume 6 feet away from my head. A minute after that, there was a sudden and unexpected attack on my cocoon by a couple of unseen perpetrators, most likely ukukus, who ran by giving me a passing prod, possibly to mock my first-world-style comfort. But after that, I slept soundly for four refreshing hours.

I was woken by somebody kicking my feet, urging me to get ready. I emerged from my warm den to find a thick coating of frost on the outside of my sleeping bag. I silently cursed the angel of the rock for the untimely wake-up call, packed up hastily, and headed into the moonlit night.

It’s two o’clock in the morning and at last I understand why I’m here. All I’ve seen and heard over the last few days finally clicked into place when we stopped for a rest on our nocturnal trek and I watched as a line of pilgrims passed by, silhouetted against the full moon, the campesina women distinctive figures in their multilayered woollen skirts. For the first time, I understood that I am truly on a pilgrimage. Qoyllur Rit’i is a pilgrimage in itself, but so is my whole trip to Peru. My fellow pilgrims are here to test themselves physically and to recharge their spirituality, and so am I. I’ve been trying to make sense of this through words, which hasn’t worked, especially as the pilgrims’ first language is Quechua and mine is English, and none of us speak Spanish well. But my new understanding transcends words. Even though we come from different worlds, I finally know that I am part of this brotherhood of pilgrims; I belong here.

This deep knowledge of our unity of purpose stayed with me as we marched on through the night, guided by the stars of the Southern Cross, the men at the front of our little procession bearing two embroidered standards on frames shaped like crucifixes. The bells on the costumes of the ukukus tinkled softly as they walked, and a distant drum beat the now-familiar one, two, three-and-a-four.

There was sacred purity in our nocturnal trek. I could see enough of our surroundings by the bright light of the moon to appreciate the Andean grandeur, but not enough to be distracted by it. The mood was contemplative, meditative, lulled by the rhythms of the drums and the bells. There was the occasional outburst of banter and laughter, but mostly we walked in silence. Where the path was rough and stumbly underfoot, or where the shadow cast by a hill blotted out the moonlight, I turned on my head torch to light my way, but I preferred to walk, as the others did, without artificial light. I felt calm and content, part of my mind focused on walking surefootedly, but the rest free to wander, free in the timelessness of an obscure hour in a strange land on a beautiful moonlit night.

It’s half-past four in the morning and we’ve stopped for another rest break. My fellow pilgrims are snoring softly around me, but I’m not sleepy. I’m leaning back against my rucksack, smoking a cigarette to calm my hunger, contemplating the sky. Stars are glimmering through the gaps in the fish scales of cloud. It bodes well for a good sunrise, which would be a welcome reward after walking the best part of fifteen miles to see it.

The Catholic veneer of the first few days of the pilgrimage has melted away, and now I feel the ancient, animistic Inca faith emerging. We have appeased the mountain spirits who have the power to grant feast or famine, fortune or failure. We’ve paid homage to the various elements of earth and sky, and now we’re walking by the light of the moon and stars to see the sun rise on the sacred mountain of Ausangate.

The festival at dawn was all the more dazzling for its contrast with the quiet calm of the night. In the shady morning twilight, shaggy coats, magnificent feathered headdresses and masks magically appeared out of makeshift rucksacks and were swiftly donned. The pilgrims lined up along the brow of a hill, their costumes glowing in jewel colours in the soft predawn light. Ranks of flags – the red and white of the Peruvian national flag and the rainbow stripes of the Inca flag – fluttered from handheld banner poles. We faced towards Ausangate, now in the far distance, waiting for the sun to rise. As the sun peeked over the horizon, it slanted across the mountain vista to strike the distant snowcap. This was the signal for the start of an exuberant pageant, the participants charging back and forth across the crest of the hill, shaking hands with their fellow pilgrims and greeting the sun. I wandered up and down the line, mesmerised, absorbing the impassioned energy of the celebrations.

According to Abel, the final hilltop celebration was about the sun first, and El Señor (the Catholic Christ) second – and a distant second, I would say. The pilgrims gather at dawn to give thanks to the sun for light and health and food in an energetic celebration of life, reciprocating the life-giving energy of the sun.

As the hilltop celebrations were drawing to a close, I walked alone down to the village while my compadres went to the chapel to complete their devotions. I looked back at where I had come from, at the celebrants streaming down the hillside in two intersecting diagonal lines, a huge human cross against the green grass, skipping and running with infectious exuberance and sheer wholehearted passion for life.

I was ambushed by an unexpected upwelling of emotion, an enormous affection for this magical land of Peru and its people. Words failed me, for once. I couldn’t articulate, even to myself, why my heart felt so full. It could have been the unbridled ecstasy of the pilgrims, or the beauty of the starlit trek, or the groundedness of sleeping on the earth for the last few nights, or the sense that I was coming home to myself and my inborn love of adventure, or appreciation for the series of serendipities and synchronicities that had brought me to this country and this valley and this new life I was crafting for myself. All I knew for sure was that I was overflowing with bliss, and I walked down the hill with tears of joy in my eyes.

Peru may seem like a strange place to start this story, but it’s as good a place as any. It was 2003 and I was 35 years old, recently jobless and divorced, when I spent three and a half months in Peru. It was the first time I’d been backpacking – mostly unscheduled, spontaneous and free – and the journey set many of the themes that have dominated my life ever since.

I can trace my deep and abiding concern for our Earth back to this trip, and specifically back to that glacier on the sacred mountain above Cusco. My fellow pilgrims told me that each year they had to trek a bit further to reach the glacier at the summit of Ausangate, the focus of their celebrations, because it was retreating as it melted. This was my first encounter with the real-world impacts of climate change, and it hit me hard. I felt I absolutely must do something, anything, to raise awareness and spark action, as a matter of the utmost urgency. It may seem like a major leap of logic to get from melting glaciers to ocean rowing, but I can only say that it was the least logic-driven decision I’ve ever made, and also the best. The day when the idea seized hold of me was about six months after I’d resolved to take action, six months of growing frustration as I sensed the clock ticking, every passing day bringing more and more environmental damage, yet completely at a loss as to what I could do to contribute to the cause. I had wracked my brains, but found no answer. Turns out, my brains are rarely the best source of truly original ideas. The best so-called brainwaves come from somewhere else.

Inspiration finally struck when I was on a long drive north to my parents’ home in Yorkshire, thinking of nothing in particular, just autopiloting along with my brain in neutral. I was aware of the obscure and masochistic sport of ocean rowing via a friend, Dan Byles, who had rowed across the Atlantic with his mother in 1997 in the first ever Atlantic rowing race, but it hadn’t struck me as a fun or sensible thing to do. Yes, I had two half-blues for rowing for Oxford in the annual races against Cambridge, but rowing across oceans was most definitely not on my bucket list. Frankly, I was terrified of the ocean, having often dreamed about drowning when I was a little girl. I wasn’t all that keen on exercise either; although I’d done a lot of rowing and running, it was mostly motivated by vanity rather than something I enjoyed for its own sake.

Where this idea came from, I will never know for sure. I like to think of it as an idea that wanted to happen, and pounced on me in a moment of vulnerability when my ego’s guard was down. In my heart, I immediately knew it was exactly the project I’d been looking for. A split second later, my ego-mind weighed in, pointing out a hundred reasons why this was the worst idea ever. But over the course of a week, my mind gradually caught up with what my heart had known all along – that this was perfect for me.

From Peru to the Pacific

So it was that, four years after receiving that resounding call to adventure, I found myself in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. After rowing the Atlantic in 2005, I was continuing my mission to row the world’s Big Three oceans, and the Pacific was next. After a failed attempt in 2007, this was now 2008 and I was trying again.

The Pacific Ocean is big. Really big.

This might be stating the obvious, but when I was planning to row it, I was quite shocked at just how mind-bogglingly big it is, so indulge me while I share some statistics. If I tell you it’s about 64 million square miles, that’s quite hard to imagine, so to put it a different way: if you took all the continents in the world and put them in the Pacific, you would still have enough room for another entire Africa.

And that’s just the surface area. When you consider its volume, factoring in an average depth of 1 mile, bottoming out at 7 miles deep in the Mariana Trench, the Pacific is around 170 million cubic miles, just over half of all the oceanic water on the planet. This equates to over half the liveable volume of the Earth, because creatures can live throughout the water column, compared with the land, where most creatures live within a narrow band above and below ground level.

Enormous as the Pacific is, we have managed to pollute just about every last cubic inch of it with plastic.

You’ve probably heard of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which I’ve heard described as an island of floating trash the size of Texas. I’ve been asked many times if I saw it. No, I didn’t. I’m not saying it’s not there, but on my way from San Francisco to Hawai’i on the first leg of my Pacific crossing, I skirted around the edges of the Garbage Patch, and although I saw a few items of recognisable plastic, like a fishing net, mooring buoys and the occasional plastic bottle, I certainly didn’t see anything you could describe as an island.

What I did see, however, is maybe more sinister. A few hundred miles east of Hawai’i, I met up with a couple of researchers on board an exceedingly homemade vessel – using the most generous interpretation of the word ‘vessel’ – made out of rubbish, and appropriately enough, called the Junk Raft.2 Joel and Marcus showed me what they were finding in the manta trawl that they towed behind their boat periodically throughout the day to test how much plastic was in the water. The pieces they were finding were mostly tiny, just a few millimetres in size, invisible to the casual observer.

This may sound less horrific than the rumours I’d heard of floating TV sets, abandoned yachts and giant accumulations of ghost nets (discarded fishing nets), but the bad news is that these fragments are perfectly sized to make a handy snack for small fish, so they get into the oceanic food chain lower down, and accumulate to higher levels as they move up. As Joel and Marcus told me, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is less of a patch, and more of a smog: diffuse clouds of plastic made brittle by exposure to sunlight and then pounded to pieces by waves. This makes it tremendously difficult to get the plastic out of the ocean without also taking out the good stuff, the plankton that form the bottom of the oceanic food pyramid.

In Hawai’i a few weeks later, I met up with the Hunks on the Junk (as the media had dubbed them) at a beach clean-up on Kahuku Beach on O’ahu’s north-east coast. It is a rarely visited beach, so any litter that shows up there is unlikely to be left by day trippers and more likely to have been washed up from the ocean. I was shocked to see the amount of debris. Where I might expect to see lines of seaweed, instead I saw tidemarks of trash, most of it plastic. We took away about twenty bags of rubbish that day, but there was still plenty left lying on the sand, and an almost endless supply lurking offshore in the Garbage Patch, waiting to roll in on the next tide.

I was a frequent spokesperson on the plastic pollution issue around that time, not because I thought it was the most pressing issue, but because it seemed like a good gateway into environmental action. Climate change, for example, can be a tough sell. It’s much easier for most people to picture how much disposable plastic they are using than it is for them to imagine a cloud of invisible greenhouse gases. And although I know they exist, I haven’t yet knowingly met a plastic pollution denier. I was working on the assumption that a photograph of a tropical beach covered in plastic rubbish, or a turtle eating a plastic bag, or a seal ensnared in a packing strap, is more likely to evoke a visceral reaction – and hopefully action – than a hockey stick graph of carbon emissions.

I have to confess, then, that I fell into the common trap of addressing the problem that seems solvable, rather than the one that’s the most important. I’m not saying that plastic pollution isn’t important, nor am I saying that climate change should be the highest priority – I’m merely noting the human tendency to focus on cleaning up the elephant poop, rather than tackling the environmental elephant in the room.

The following year, after a winter of rest, recuperation and reprovisioning, I set out from Hawai’i and rowed the second leg of the Pacific, making landfall 104 days later in the Republic of Kiribati, a small island nation of about 100,000 souls, lying on both the equator and the International Date Line. It’s the only country in the world that straddles all four hemispheres and consists of thirty-three low-lying islands, mostly less than 6 feet above sea level.

Understandably, its citizens are apprehensive about the future. Global mean sea level has risen between 8 and 9 inches (21–24 centimetres) since 1880, with about a third of that happening in the last twenty-five years. The rising water level is mostly due to thermal expansion of seawater as global temperatures rise, plus meltwater from ice caps and glaciers like the one I had seen in Peru.

Although 8 or 9 inches may not sound like much, when most of your country consists of coral atolls that barely protrude above sea level, it matters. When you consider that Kiribati has a land area of 313 square miles and 710 miles of coastline, it’s clear that nowhere in the country is far from the rising tide.

Even before the atolls are inundated, increasing tropical storms are going to cause major problems, overreaching fringing reefs, contaminating fresh water supplies with seawater and washing away the fragile causeways that link the more inhabited islands. I met with President Anote Tong, who in our videoed conversation shared his fears for the future of his country.

I saw him again that December at the COP15 climate change conference, hosted by the United Nations in Copenhagen. It was the last Friday of the conference and he and his small delegation invited me to join them for dinner in an Indian restaurant. The conference had just ended in disappointment. The UN process had broken down, most of the national delegations had been excluded from the final rounds of talks (the Copenhagen Accord was drafted by only five countries: the United States, China, India, Brazil and South Africa), and there had been no fair and binding deal. While the conference had recognised that keeping average global temperature rise below 2°C would be a good thing, it made no commitments for reducing emissions in order to achieve the target, and had dropped proposals to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C and to cut CO2 emissions by 80 per cent by 2050. The developed world pledged to help poor countries adapt to climate change, and offered to pay them to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (the REDD+ framework).

In effect, the failure of the conference had signed the death warrant for Kiribati and many of the other small island nations. In their speeches that night, the I-Kiribati contingent spoke brave words, but their despondency was palpable. ‘We are trying to maintain our composure, but I am very sad,’ President Anote Tong said to me. ‘We were naïve and vulnerable. I wish I was so much more ruthless.’

I felt deep sadness for this dignified, elegant man, educated in New Zealand and with a master’s degree from the London School of Economics. There was cruel irony in the fact that his studies of economics had not been able to prevent his country becoming collateral damage to neoliberal capitalism.

The following year, the president came down to the dock in Kiribati to wave me off on the third and final stage of my Pacific crossing. In his speech, he thanked me for my efforts in bringing attention to the plight of his country. As I rowed away, I reflected on the direness of their situation, and the pathetic insignificance of my endeavours on their behalf. I wondered how I would feel if it were my country destined to disappear under the waves, drowning the places where I had been born, grown up, gone to school, and where my ancestors were buried. I couldn’t help thinking that if their economy was worth $15 trillion (US GDP for 2010) rather than $150 million (Kiribati GDP for 2010), their future would be taken much more seriously by the global community. As it was, this proud island nation was apparently seen as dispensable.

A Crisis of Conferences

Immediately before I set out on that last leg of my voyage, from Kiribati to Papua New Guinea, I spoke at a TED conference on board the National Geographic Endeavour in the Galapagos Islands, in honour of the renowned American marine biologist Sylvia Earle and her TED Prize-winning wish to protect our oceans.

On the one hand, the conference was good for my ego, rubbing shoulders with a star-studded audience including A-list celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Edward Norton, Glenn Close, Chevy Chase, Damien Rice and Jackson Browne. On the other hand, it was bloody depressing. Species extinction, ocean acidification, collapsing fish stocks, coral reef destruction, fossil fuel extraction, sewage, agricultural run-off, sea dumping, mining, plastic pollution, toxic pollutants like PCBs and DDT – amidst all these attacks and acronyms there seemed to be precious little hope for the survival of the oceans, and hence the survival of anything else on this planet. Jeremy Jackson, a gaunt marine ecologist rejoicing in the moniker of Doctor Doom, put the final nail in the coffin of my morale with his talk, entitled ‘How We Wrecked The Oceans’. It made me want to curl up in despair rather than keep rowing.

But keep rowing I did, and after a total of 250 days at sea since leaving San Francisco, I completed my Pacific crossing in Madang, Papua New Guinea. The official estimate was that 5,000 people turned out to greet me. I can only vouch for the fact that there were a lot, including many in decorated canoes and traditional costumes, others waving homemade banners bearing my name, and I was given more gifts than I could carry. I was overwhelmed by the warmth of the welcome.

The day after I arrived, there was a major demonstration in the capital, Port Moresby, to protest against government corruption. The big news in Madang, meanwhile, was the ongoing controversy over a Chinese-owned nickel mine that was being constructed in the jungle nearby. There were three big counts against the mine: concerns that the tailings would damage the reefs of the Coral Triangle; the mine being staffed entirely by Chinese, with no jobs for the local people; and the mining company being given a twenty-five-year tax break by the Papua New Guinea government. These complaints, particularly the last, seemed not entirely unrelated to the anti-corruption protests.

During my time in Madang I also learned of families selling their ancestral land to logging companies, sacrificing their family’s future in favour of present profit, and of the widespread exploitation of Papua New Guinea’s rich natural resources by foreign companies taking advantage of this relatively new and chaotic country, with its 851 languages and a largely rural, tribal population. Papua New Guinea is one of the world’s least well-documented countries, but is believed to have numerous uncontacted tribes, and many species of plants and animals as yet undiscovered. I could almost sense greedy first-world corporations drooling in anticipation as they contemplated its natural riches, corruptible politicians, financially unsophisticated tribespeople and inadequate environmental protections.

Over the course of the years, as many ocean miles passed under the hull of my rowboat and I continued to show up for conferences and marches, it was dawning on me that there was much more to solving this ecological crisis than simply pointing out to decent folks that we have a problem. Even the conferences themselves, with the notable exception of TED Mission Blue in the Galapagos Islands, often seemed abstracted, transactional and businesslike, with few reminders in the conference halls of the precious natural world we were supposedly trying to protect. Presentations often centred around scientific data, cost-benefit analyses and business cases. There was a lot of head and precious little heart – the dynamic that created the problems in the first place.

Ecological damage has been generated primarily by the more developed world, and suffered primarily by the less developed world. There is a geographical disconnect, compounded by wilful blindness. As the environmental journalist George Monbiot said at a talk I attended in Copenhagen, the attitude of the Global North seems to be: ‘If I swing my fist and my neighbour’s nose happens to get in the way … tough.’ The economic disparity between the Global North and the Global South allows the North to continue its exploitation, and affords it the luxury of insulating itself from the worst impacts.

This colonialist attitude is written into every climate change agreement there’s ever been. Look at the Copenhagen pledges as an example: the developed world pledged to help poor countries adapt to climate change. Translates to: ‘We’ve screwed your country – oops, sorry, here’s some money.’ They also offered to pay developing countries to reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation. Translates to: ‘We’ve deforested and degraded your country for the last couple of centuries, but we don’t want you to do the same. Here – have some more money.’

While in Copenhagen I spent time with a new friend, the Scottish barrister and author of Eradicating Ecocide, Polly Higgins. She vehemently opposed the monetary valuation of nature, seeing it as sacred in its own right, regardless of what it delivers to humans in ecosystem services. Polly was an inspiring visionary and big-hearted human being. She died too soon, aged 50, in 2019, less than a month after being diagnosed with an aggressive cancer. She lives on, though, in the ideas she sowed and the campaigns she started. In particular, she could see that corporations would continue to exploit our planet while the only penalty they faced was a financial slap on the wrist. Her dream was to have ecocide recognised as an international crime, alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression, for which CEOs could be prosecuted and sent to prison. Her dream hasn’t yet come true, but the work continues.

It seemed to me increasingly clear that we were trying to solve the environmental problems from the level of economic consciousness that created them. The prevailing attitude seemed to be that everything had its price, from trees to oceans to people. If you had enough money to throw at the problem, you could pay off the poor, bribe politicians and spend your way out of environmental legislation as an acceptable cost of doing business.

Some things are precious beyond price, and yet I went to ocean conference after environmental conference where the talk was all about money – money for research, money for conservation, money for mitigation and adaptation and compensation. When I went to a conference hosted by The Economist (which should have been a clue) and the discussion turned to coral reef insurance, I felt sick. It was becoming increasingly clear to me that we couldn’t fix our ecology without first fixing our economy.

Chapter 2

Economics

‘A stark choice faces humanity: save the planet and ditch capitalism, or save capitalism and ditch the planet.’1

Fawzi Ibrahim

In 2018 I was invited to the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, for a conference called the Global Economic Visioning. This was the same hotel – a grand, turreted edifice, white-walled with a bright red roof, set against the dramatic backdrop of Mount Washington, the highest mountain in the north-eastern US – where the original Bretton Woods conference had taken place in 1944.

For a while, I’d been interested in economics as a leverage point for environmental change – or, conversely, as the rock on which such change too often foundered – but realised I didn’t know much about the first Bretton Woods, or, as it was officially called, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference. It was time for some homework.

Towards the end of the Second World War, for three weeks in July 1944, 730 delegates (all men) from the forty-four Allied Nations convened at Mount Washington. The most pressing issue of the day was how to prevent another world war, this one having arisen, at least in part, out of the economic misery in Germany resulting from post-war reparations and compounded by the Great Depression, providing fertile ground for fascist ideas to take root.

The British delegate, John Maynard Keynes, was the key figure at the conference. He argued that the rise of protectionism (the imposition of tariffs on imported goods) across the industrialised world had contributed to low aggregate demand: people weren’t buying enough stuff because prices were too high, and the economy had ground to a halt. For Keynes, excess protectionism was a primary driver of the Great Depression, so the goal of the new General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was to reduce tariffs across the board in order to boost demand.

In other words, the GATT began its life as an ostensibly benevolent institution, intended to promote economic stability and peace. Just like the original International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, founded during the same conference, it was rooted in Keynesian principles of full employment and economic stability, and intended to contribute to the collective good.

For many years the Bretton Woods Agreement worked well, but things started to go awry in 1971 when Richard Nixon unilaterally withdrew the US from the gold standard, meaning that the dollar no longer represented something with real value – actual gold – and instead became bits of paper and cheap metal that had value only because people believed they had value. Currency became a fiction that worked only because everybody agreed to believe the same story.

Before 1971, the US could only print as much money as was backed by its gold reserves, but now it could print as much money as it liked. And because the US dollar was the global reserve currency, meaning it was the default currency for international transactions, this put the US at a huge advantage. For any other country to obtain US$100, it had to produce goods or services worth $100 and sell them. For the US to obtain $100, it simply printed them.

In the 1980s, further blows were dealt to the spirit of the Bretton Woods Agreement. The economic stability that had been a key objective depended on tight financial regulation, but under Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan regulations were relaxed or removed altogether. Free trade reforms dismantled many of the capital controls that were intended to protect the stability of national economies. Investors could now withdraw their capital at short notice from a particular country if they thought they could make more money elsewhere, and if several investors did this at once, it could devastate a country’s economy.

For several decades, there had been increasingly loud calls for a new Bretton Woods, particularly to create a new international framework to tackle several pressing issues: the unfettered capital flows that were creating global financial crises; a far from level playing field in terms of each nation’s access to capital; and the exclusion of many developing countries from economic progress and political participation.

The conference I attended was interesting, with an outstanding opening session featuring two of my favourite thinkers, Charles Eisenstein and Daniel Schmachtenberger, but the new Bretton Woods it wasn’t. There was a lot of excitement about cryptocurrencies, some of which have potential, but most of which are being used for old-school, get-rich-quick speculation, just like any other commodity. Cryptocurrencies used this way may as well be gold, oil or pork bellies. To be fair, the conference didn’t set out to overhaul the entire global economic model – its stated goal was to update the conversation, incorporating newfangled, post-1944 developments like the internet, crypto and the radical idea that women might have something valuable to contribute to the debate.

My preparation for the conference, and my frustration at its limitations, helped me clarify my personal view on what we need in the way of economic reform. My grade A in A-Level economics hardly qualifies me to pontificate on the state of global capitalism, but from my simplistic perspective, some things seem quite obvious. I believe we need to step outside our current story of money, and take a long hard look at our economic system from the outside. We created capitalism, and while it has brought many benefits, it is also encouraging the destruction of our ecosystems, and widening the gulfs of inequality both within and between nations.

There are many signs that the old story of money isn’t working – the dubious correlation between money and happiness, how we’ve been brainwashed into buying stuff we don’t need, the non-stop accumulation of wealth and debt, externalisation of (environmental) costs, corporate lobbying, misinformation campaigns, business-sponsored science, short-termism and much more besides. These are huge topics, and by necessity I’m only skimming the surface of a few selected themes.

To be clear, I have nothing against money, capitalism, currencies, cryptocurrencies, economics, economists or anything else in this arena. I’m in favour of anything, so long as it delivers the greatest good to the greatest number over the longest possible period of time. If a story doesn’t contribute to that objective – recalling that money is just a story – then it’s worth seeing if we can come up with a more effective one.

My sense is that we need to come up with a vision of the world we want to create – for example, a world of peace, sustainability and fairness – and reverse engineer from there to figure out what principles and structures will support that vision. The system we have now isn’t working – not for the planet, not for the developing world, and not for 99 per cent of the people in the developed world. We can do better than this.

Metrics of Success

In 2012, I was fortunate enough to be one of sixteen international Fellows selected for the Yale World Fellowship Programme (of which more later). One of the other Fellows tipped me off that Open Society International was offering grants to fund transformative projects. Fired up with world-changing zeal by my time on the programme, and otherwise in a between-roles phase of my life, I decided to give it a shot.

I prepared an application for a project I called the New Prosperity Paradigm. I had come to believe we need a new definition of success, accompanied by a new metric to replace gross domestic product (GDP). The evidence, as I saw it, suggests that our current definition of success, based on fame, fortune or position, is not enhancing happiness and wellbeing, but instead is delivering material aspirations that run counter to the wellbeing of the planet, as well as to the wellbeing of humans.

This was my central premise: up to a certain point, yet to be achieved by many developing countries, rising income undoubtedly correlates to rising wellbeing. But once basic needs are met, the marginal benefits of additional income rapidly diminish – but consumption does not. Additional purchasing power doesn’t yield a proportionate increase in current wellbeing, and in terms of resource extraction and environmental pollution, it seriously impacts on the potential wellbeing of future generations.

Ultimately, my grant application failed in the sense that I didn’t get my project funded. But it succeeded in that I learned a lot about the global economy and the way it’s exploiting the vast majority of humanity, as well as causing enormous damage to the natural world. I wouldn’t mind so much that we are trashing our Earth if it was making us happier, but it’s not – not even the rich folks.

The conventional approach is based on a faulty assumption: that the best way to measure improvement in living standards of a country is by looking at the growth rate of its gross domestic product per capita, which refers to the value of goods and services produced within a country’s borders. But does rising GDP cause a widespread rise in the standard of living? And does standard of living equal quality of life? It would seem not.

As Robert F. Kennedy famously said of GDP in his campaign speech in 1968, ‘It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.’2 Even the creator of the GDP metric, Simon Kuznets, said in 1934, ‘The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.’3 A quick online search yields dozens of quotes about the inadequacy of GDP (and also of its close cousin, GNP, gross national product, which is the value of goods and services produced by a country’s citizens both domestically and abroad). Those critics range from Ban Ki-Moon, former UN secretary-general, to the late Robert McNamara, former president of the World Bank.4 In Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth points out that we have been fixated on GDP for over seventy years, and that this fixation has been used to justify extreme inequality and the unbridled destruction of the natural world. She advocates for a new goal – ensuring that human rights are met for all, within the limits of our planetary boundaries.5

GDP has been weaponised by multinational corporations in the oppression and exploitation of less developed countries, as John Perkins describes in Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. His job was to convince foreign governments to embark on massive infrastructure projects ‘intended to create large profits for the contractors, and to make a handful of wealthy and influential families in the receiving countries very happy, while assuring the long-term financial dependence and therefore the political loyalty of governments around the world. The larger the loan, the better.’6 Why would foreign governments agree to such exploitative contracts? They were persuaded by outrageously optimistic promises of GDP growth, which would make them look good to their citizens and to their peers on the global stage.

It’s not only leaders of less developed countries that are susceptible to GDP vanity. Professor Tim Jackson writes, speaks and advises extensively on prosperity without growth. He tells the story of being summoned to meet with a senior adviser at the UK Treasury, where he was invited to set out his stall: he spoke of how our addiction to ever-increasing GDP is destroying the planet; the challenges of decoupling economic growth from unsustainable practices; and the necessity of supplanting consumerism with a different conception of prosperity based on genuine wellbeing. The adviser listened carefully, then asked, ‘What would it be like for Treasury officials to turn up at G7 meetings knowing that the UK’s GDP had slipped down the rankings?’

Jackson says he was ‘dumbstruck’ by this response. ‘How could I have missed that the politics of the playground is evidently still in action, even in the highest echelons of power?’7 Apparently, the preservation of the planet is less important than a Treasury official’s ego.

The trouble is that GDP deceives us with its reductionist simplicity. In a world that finds it preferable to measure quantities rather than qualities, it pretends to be a proxy for human thriving. We know it’s a crude metric – it includes as positives many things that are clearly antithetical to wellbeing, such as the cost of wars, cancer care, rebuilding houses destroyed by wildfires, and depression medications, while ignoring the beautiful immeasurables of love, joy, fulfilment, relationship and laughter.

And yet we still use it. It takes the glorious messiness of human society and boils it down to a single number, enabling a government to show that the number is getting bigger under its leadership, or that its number is bigger than another country’s number. It’s a blunt instrument used to bludgeon us into believing that things are getting better, when mostly they aren’t.

Incentives

If GDP is the measure of a nation’s success, then profits are the measure of a corporation’s success, and both metrics suffer from many of the same problems. My fundamental issue with laissez-faire (aka free-for-all) capitalism is its incentives. As billionaire investor Charlie Munger says, ‘Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.’8 Every animal, including humans, is designed to seek rewards, and will adjust its behaviour accordingly: a dog for a biscuit, a dolphin for a fish, a banker for a bonus.

While profit maximisation is the preeminent goal, so far ahead of any other goal that the others have just about disappeared over the horizon, executives are incentivised to overlook minor little things like destroying the Earth and exploiting humans as if they were just another resource to be used up and worn out. They are rewarded for perpetually feeding and growing the bottom line, even if that is best served by increasing misery, waging war or exploiting natural disasters. John Maynard Keynes summed it up, ‘Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.’9

This isn’t personal. Many executives are good people, and many companies do good things. I’m just saying that a system that prioritises profit over all else encourages the people who work within that system to set aside morals or scruples if there is a fast buck to be had. If what you measure is what you get, then measuring profit but neglecting principles will inevitably lead to unprincipled behaviour.