Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Parisi were a tribe located somewhere within the present day East Riding of Yorkshire, UK, known from a brief reference by Ptolemy. They were originally immigrants from Gaul and share their name with the tribe that occupied modern day France. Fairly obvious from their name, they gave the French capital its name. The investigation of the Parisi began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, following the trend for antiquarian exploration elsewhere in Britain. Before that the remains of Roman buildings encountered in medieval East Yorkshire were treated with little respect and used as a resource. The Parisi tells this captivating story of the history of the archaeology of the Parisi, from the initial investigations in the sixteenth century right through to modern day investigations.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 576

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

List of Plates

Introduction

Chapter 1 The Search for the Parisi

Chapter 2 The Landscape of Eastern Yorkshire

Chapter 3 The Emergence of a Tribal Society

Chapter 4 The Arras Culture

Chapter 5 Settlement and Economy in Iron Age Eastern Yorkshire

Chapter 6 Later Iron Age Eastern Yorkshire and the Coming of Rome

Chapter 7 The Impact of Rome – The Larger Settlements

Chapter 8 The Impact of Rome – The Countryside

Chapter 9 Crafts and Industry

Chapter 10 The Individual in Roman Eastern Yorkshire

Chapter 11 From the Parisi to Deira

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book of this kind would not be possible without the contribution of many people. I would like to thank all those who have shared their ideas on Iron Age and Roman East Yorkshire with me, particularly Lindsay Allason-Jones, John Collis, John Creighton, Peter Crew, John Dent, Peter Didsbury, Melanie Giles, Ian Armit, Ian Haynes, Martin Henig, Yvonne Inall, Jim Innes, Rod Mackey, Peter Makey, Terry Manby, Martin Millett (my collaborator in the Foulness Valley project), Tom Moore, Patrick Ottaway, Mark Pearce, Rachel Pope, Jenny Price, Dominic Powlesland, Steve Roskams, Steve Sherlock, Bryan Sitch, Ian Stead, Jeremy Taylor, Steve Willis and Pete Wilson. I am grateful to many past and present students from the University of Hull, especially those who undertook research in the territory of the Parisi; their work is acknowledged in the text and bibliography, and also my archaeological colleagues there, Helen Fenwick and Malcolm Lillie.

I am very grateful to all those members of ERAS and YAS and CBA Yorkshire who have participated in fieldwork and listened to reports on work at various stages. I would like to thanks Dave Evans, Ruth Atkinson, Trevor Brigham and Ken Steedman from Humber Archaeology Partnership and the North Yorkshire Historic Environment Record and to John Oxley, York City Archaeologist, for supplying much data and information. Paula Gentil and Caroline Rhodes of Hull Museums allowed access to finds for photography and research and generously gave of their time. David Marchant of the East Riding Museums Service and Andrew Morrison of the Yorkshire Museum also kindly supplied access to finds and other information. Ann Clark and Malcolm Barnard of Malton Museum were very helpful in allowing access to finds. Jody Joy kindly supplied images from the British Museum and valued comment.

Special thanks must go to John Deverell and Mark Norman who helped me compile the database behind the distribution maps, putting in much work. Naomi Sewpaul, John Dent and Pete Wilson kindly read and commented on the text. Big thanks go to Mike Park, photographer at Hull University, who has provided some stunning images, and to Tom Sparrow and Helen Woodhouse for spending a great deal of time and effort on maps and other drawings for which The Marc Fitch Fund kindly provided some funding.

The book benefitted from several periods of research leave provided by the History Department and Faculty of Arts, University of Hull. I am very grateful to the various editors from The History Press, particularly Emily Locke, Ruth Boyes and Glad Stockdale, who have been very patient and helpful. Finally many thanks to my family for all their support during the writing of this book.

Figures and plates are acknowledged in the captions. Figures 2, 8, 9, 11, 15, 24, 32, 34, 49, 56, 71, 77, 79, 84 and Plate 17 are © crown copyright/database right 2013. An Ordnance Survey/EDINA supplied service, for the background topographical data.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig. 1 Europe showing distribution of chariot burials.

Fig. 2 Eastern Yorkshire showing the main places mentioned in the text of Chapter 1.

Fig. 3 3a. Boynton, Mortimer and Greenwell excavating at Danes Graves, 1898.

3b. Drawing of the Danes Graves chariot burial (Mortimer 1905, 359)

3c. Copper-alloy pin decorated with coral from Danes Graves.

Fig. 4 Excavation at Pot Hill, Throlam.

Fig. 5 The ‘staff’ at Brough, 22 August 1936.

Fig. 6 The Brough theatre inscription as found.

Fig. 7 Simplified geological map of eastern Yorkshire. Based on British Geological Survey data.

Fig. 8 The major topographical features of eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 9 The area around Grimthorpe and Huggate dykes.

Fig. 10 Comparative plans of curvilinear enclosures and hill forts.

Fig. 11 The relationship between linear earthworks, larger hill forts and curvilinear enclosures on the Yorkshire Wolds and Foulness Valley.

Fig. 12 Reconstruction of Staple Howe.

Fig. 13 Scorborough square barrow cemetery from the air.

Fig. 14 The Arras square barrow cemetery from the air.

Fig. 15 The distribution of square barrows against the topography of eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 16 Garton Slack chariot burial 1971.

Fig. 17 Garton Station chariot burial 1985.

Fig. 18 Kirkburn burial K3 (after Stead 1991).

Fig. 19 The roundhouse at Burnby Lane, Hayton under excavation.

Fig. 20 Reconstruction of the roundhouse at Burnby Lane, Hayton.

Fig. 21 Plan of the Wetwang Slack settlement (after Dent).

Fig. 22 Cropmark of the Bursea Grange settlement.

Fig. 23 Iron Age settlement plans.

Fig. 24 Iron Age settlements.

Fig. 25 Plan of the ‘ladder settlement’ at Arras.

Fig. 26 Iron Age querns from the Rudston area.

Fig. 27 Reconstruction of the Hasholme logboat.

Fig. 28 Iron working tools from Garton Slack.

Fig. 29 The Gransmoor currency bar.

Fig. 30 Early Middle and later Iron Age pottery from eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 31 Plan of the Brantingham settlement.

Fig. 32 Distribution of later Iron Age coins and ‘Dragonby style’ pottery.

Fig. 33 Chalk figurines from eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 34 Roman forts roads and first century activity.

Fig. 35 Plan of Brough Roman fort.

Fig. 36 Malton Roman fort.

Fig. 37 Excavating the defences of Malton fort in Orchard Field.

Fig. 38 Roman artillery ammunition from Malton. Stone balls and a ballista bolt.

Fig. 39 Head pot from Holme-on-Spalding Moor.

Fig. 40 Brough from the air.

Fig. 41 Lead pigs from East Yorkshire.

Fig. 42 Roman Brough.

Fig. 43 The Brough theatre inscription.

Fig. 44 Roman Malton and Norton.

Fig. 45 Roman roadside settlement at Hayton.

Fig. 46 Roman Shiptonthorpe.

Fig. 47 Writing tablets from the waterhole at Shiptonthorpe.

Fig. 48 Roman Stamford Bridge.

Fig. 49 Roman rural settlements in eastern Yorkshire (excluding villas).

Fig. 50 Villa plans in eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 51 The development of the Welton villa.

Fig. 52 The bath suite of the settlement at Burnby Lane, Hayton under excavation.

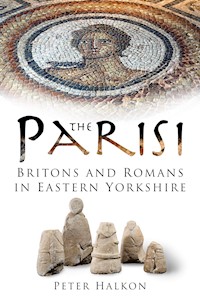

Fig. 53 The head of Spring from the Charioteer mosaic, Rudston.

Fig. 54 Corder’s excavation at Langton villa.

Fig. 55 A scythe blade and millstone in a pit at Welton Wold.

Fig. 56 The Roman pottery kilns of eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 57 A comparison of the pottery kilns of eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 58 Romano-British pottery forms from eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 59 Kiln 2 from Hasholme Hall.

Fig. 60 Pottery from Holme-on-Spalding Moor.

Fig. 61 The iron anvil from Hasholme.

Fig. 62 Textile equipment from Roman Malton.

Fig. 63 Close up of a patera handle from Malton bearing the punched name Lucius Servenius.

Fig. 64 The altar of Victory from Bolton.

Fig. 65 Figurine of Apollo the lyre player from the Roman roadside settlement at Hayton.

Fig. 66 Votive figures of a sheep and chicken from Hayton.

Fig. 67 The foundations of the possible shrine from West Heslerton.

Fig. 68 Part of a pottery vessel decorated with smith’s tools.

Fig. 69 Miniature anvil in copper alloy from Brough.

Fig. 70 The waterhole at Shiptonthorpe.

Fig. 71 The distribution of burials in Roman eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 72 Copper-alloy heads from the ‘Priest’s’ burial near Brough.

Fig. 73 Part of the face of a pipe-clay figurine found at Brough.

Fig. 74 So called lachrymatory bottles from Market Weighton.

Fig. 75 Infant burial with a jet bear from Malton.

Fig. 76 Burial from Newport Road quarry, North Cave.

Fig. 77 Distribution of the main Romano-British brooch types of eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 78 The distribution of items associated with Vulcan in Roman Britain.

Fig. 79 Roman coins by century.

Fig. 80 The walled area at Brough. Bottom: Corder shows off Tower 1.

Fig. 81 Reconstruction of a signal station from Filey.

Fig. 82 Late Roman cavalry spurs from Rudston, Beadlam and Filey.

Fig. 83 Crossbow brooches from Malton.

Fig. 84 Later Roman eastern Yorkshire.

Fig. 85 The leg bones of a woman in the flue of a crop-drier or malting oven at Welton.

Fig. 86 The cist burial cut into a pottery kiln at Crambeck.

LIST OF PLATES

Plate 1 A map of Roman Yorkshire from Drakes’s Eboracum (1736).

Plate 2 The Roos Carr images.

Plate 3 The frontispiece of Mortimer’s Forty years researches.

Plate 4 Mortimer’s (1905) map of the entrenchments around Fimber.

Plate 5 Huggate Dykes from the air.

Plate 6 Simplified soil map of eastern Yorkshire based on National Soil Research Institute mapping.

Plate 7 Section across the irrigation pond at Hasholme.

Plate 8 The Boltby Scar hill fort under excavation.

Plate 9 Finds from Paddock Hill, Thwing.

Plate 10 Reconstruction of the later phases of the later Bronze Age ring fort at Thwing.

Plate 11a Wetwang Slack chariot burial 1, 1984.

Plate 11b Wetwang Slack chariot burial 2, 1984.

Plate 12 Kirkburn chariot burial, 1987.

Plate 13 Plan of the Wetwang village chariot burial, 2001.

Plate 14 Finds from the ‘King’s Barrow’, Arras.

Plate 15 Items from the ‘Queen’s Barrow’, Arras.

Plate 16 Middle Iron Age eastern Yorkshire.

Plate 17 The Iron Age slag heap at Moore’s Farm, Welham Bridge.

Plate 18 The Hasholme logboat.

Plate 19 The Kirkburn sword.

Plate 20 The anthropomorphic hilt of the short sword from North Grimston found in 1902.

Plate 21a South Cave weapons cache.

Plate 21b Detail of a sword from the South Cave Weapons Cache.

Plate 22 Part of the hoard of Corieltauvian gold staters from Walkington.

Plate 23 Excavation in 1988 of the late Iron Age/early Roman settlement, Redcliff, North Ferriby.

Plate 24 Cropmark of Hayton Roman fort.

Plate 25 Reconstruction of a cavalryman of the ala Gallorum Picentiana.

Plate 26 Military equipment from Malton.

Plate 27 Military strap fittings from Malton.

Plate 28 Decorated ceramic chimney pot/finial from Malton.

Plate 29 Decorated limestone winged victory caryatid from Malton.

Plate 30 The so-called ‘goddess’ painted wall plaster from Malton.

Plate 31 A larger than life copper-alloy right foot from a large Roman statue found at Malton.

Plate 32 A selection of jewellery and personal items from Malton.

Plate 33a The Roman aisled hall at Shiptonthorpe

Plate 33b Reconstruction of Shiptonthorpe Hall.

Plate 33c Roman shoe from Shiptonthorpe.

Plate 33d Double-sided comb from Shiptonthorpe.

Plate 34 The Roman villas of eastern Yorkshire against the soils.

Plate 35 The ‘charioteer’ mosaic.

Plate 36 The Tyche mosaic at Brantingham.

Plate 37 The Venus mosaic from Rudston.

Plate 38 Brooches from East Yorkshire.

Plate 39 Gold earrings.

Plate 40 Reconstruction of the shrine complex at West Heslerton.

Plate 41 A member of late Roman army re-eactors Comitatus.

Plate 42 Part of a cupboard door from the well at Hayton.

Plate 43 The Goodmanham plane.

INTRODUCTION

Eboracon (Eboracum)

Legio VI Victrix (Victorious)

Camulodunum

Near a bay (gulf) suitable for a harbour (are) the Parisoi and the town (city) Petuaria.

– Ptolemy Geographia 2.3.17.

(Stückelberger and Graßhoff 2006, 154; Rivet and Smith 1979, 142.)

This is the first surviving reference to the Parisi. It was made by the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy as he is better known, who was working in Alexandria, Egypt, during the AD 140s.Writing in Greek, Ptolemy aimed to provide a description of the world as he knew it at the height of the Roman Empire. His account gives the names of its peoples and significant places in their territories across the Roman Empire and its fringes, listing the major features along coastlines such as gulfs, estuaries and promontories and their geographical position as closely as he could (Strang 1997). Like so many ancient texts, Ptolemy’s original no longer exists, and the book was handed down through various transcriptions, one of the oldest surviving versions dating from the late thirteenth century AD preserved in the Satay Library of the Topkapi palace in Istanbul, which was used in the most recent full translation into German (Stückelberger and Graßhoff 2006). Ptolemy’s account became better known through various Latin versions, hence the use here of ‘Parisi’ rather than ‘Parisoi’.

There are various meanings given for the word itself which is of Celtic origin: ‘the rulers’ or ‘the efficacious ones’, derived from paro, ‘the people of the cauldron’ which comes from pario ‘cauldron’ or ‘the spear people’, relating to the Welsh par meaning spear (Falileyev 2007, 164).

Ptolemy places the Parisi in what is now eastern Yorkshire. The last definition is particularly interesting as this region possesses an Iron Age burial ritual which involves the throwing of spears at bodies in graves (Stead 1991) which will be discussed in more detail in later chapters.

It is generally presumed, largely due to their geographical coincidence, that there is a direct relationship between Ptolemy’s Parisi and the earlier Iron Age people whose burials were placed under low mounds surrounded by small square ditches or ‘square barrows’, as the densest concentration of these features in Britain is also in this region (Stead 1979; Cunliffe 2005). Although Stead identified the Parisi with square barrows in his La Tène cultures of eastern Yorkshire (Stead 1965), he was more circumspect about this and any connection with the Parisii of Gaul mentioned by Julius Caesar (Gallic Wars 6:3) in his later books (Stead 1979; 1991).The dead in some of these monuments were accompanied by the remains of two-wheeled vehicles which are usually referred to as chariot burials, and again these are at their densest in East Yorkshire. The first reported excavation of a chariot burial was at Arras near Market Weighton 1815–17 (Stead 1979), hence the ‘Arras culture’, a label attached to these people by the archaeologist V.G. Childe (1940) because of the distinctive nature of their material remains and its restricted distribution (Fig. 1). It was presumed by a number of scholars such as Hawkes (1960) that the culture was brought in to eastern Yorkshire through an invasion from the Marne region of northern France because of the similarity between the burials in both areas, and the discovery of artefacts decorated in a style which takes its name from a middle Iron Age site at La Tène in Switzerland.

According to Hawkes (1960) this incursion followed an earlier Iron Age invasion from the European continent in the so-called Hallstatt period, named after the lake-side village in Austria associated with salt-mining, where a large cemetery with burials containing artefacts decorated in distinctive styles was excavated. The excavations by the German archaeologist Bersu (1940) on an Iron Age settlement at Little Woodbury in Wiltshire demonstrated continuity with the indigenous Bronze Age material culture, rather than continental invasion, based on the shape of houses, which were round in Britain as opposed to their mainly rectangular counterparts on the European mainland, and other aspects of material culture. When Hodson was writing in 1964, insufficient excavation had been undertaken to match square barrows to roundhouses until Brewster (1980) and Dent (1982, 456) encountered them both at Garton-Wetwang Slack. Despite this Hodson (1964) still saw the Arras culture as originating on the continent along with the Aylesford culture of south-east England.

Fig. 1 Europe showing distribution of chariot burials and key places mentioned. Based on Stead (1979) and Anthoons (2011). (H. Woodhouse)

Stead (1979, 93), in comparing burials in East Yorkshire with those on the continent, still advocated some migration:

The arrival in Yorkshire of artefacts from west-central Europe could be explained away by trade, the arrival of ideas – complex burial rites must surely mean the arrival and settlement of people. They could have been tribes but they need not have been numerically strong: perhaps they were adventurers, merchants, evangelists or a few farmers.

He also highlighted the differences, with crouched burials predominating in East Yorkshire and extended ones on the European continent, noting the great contrast in opulence between the French vehicle burials and those of East Yorkshire. By 1991, however, in the light of much excavation, especially his own at Kirkburn, Garton Station, Rudston and Burton Fleming, and those of Dent (1985) at Wetwang Slack, his hypothesis is moderated further: ‘Direct continental influence on the Arras culture amounts to two aspects of the burial rite, cart-burials and square barrows – their arrival points to at least one immigrant … a powerful – well connected evangelist?’ (Stead 1991, 228).

The impact of continental contact has therefore been progressively downplayed. Dent (1995, 65) also continued this trend: ‘Excavations of Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements have shown that there was a continuous insular cultural tradition in the region. The architecture through this period had more in common with other parts of Britain than the continent.’

Examination of the archaeological evidence on both sides of the English Channel and North Sea, however, suggests that continental links are more complex and traits regarded as ‘indigenous’ or ‘continental’ are not mutually exclusive. It has been clear for some time that there are roundhouses in France (Harding 1973; Jacques and Rossignol 2001) and further examples are still being found around Arras (France) (pers. comm. Dimitri Mathiot). Stead (1979, 38) himself points out that there are crouched burials, though very much in the minority, in the Champagne region, which also has vehicle burials and square burial enclosures. Conversely the skeleton in the ‘Kings barrow’ at Arras (East Yorkshire), buried with two horses, which is itself a unique trait in East Yorkshire vehicle burials, is not crouched but lies on his back with legs flexed (Stillingfleet 1846). Dent’s (1995, 52) and Stead’s (1991, 179) Type B burials, often accompanied by weapons and pig bones, were also extended and with the head to the east or west rather than north.

The origins of Celtic peoples and even the term ‘Celtic’ itself have become both topical and contentious in our own era of large-scale immigration and preoccupation with identity and origins (James 1999; Collis 2003). The collating and plotting of the linguistic and archaeological evidence across Europe in the comprehensive volume An Atlas for Celtic Studies (Koch 2007), provide what the writer claims is an opportunity to examine the evidence ‘free from arbitrary and passing modes of preferred analysis’ (Koch 2007, 2).

A different and still controversial approach was taken by Oppenheimer in the Origins of the British (2006) and Sykes’ Blood of the Isles (2006), who used genetics, largely the Y-chromosome of present peoples to remap past populations. Miles (2005) states on the back cover of his book, The Tribes of Britain, that ‘the English, the Irish, the Scots and the Welsh (are) … a ragbag of migrants, reflecting thousands of years of continuity and change’. A further scientific approach to determining provenance is based on the measurement of various isotopes, particularly oxygen and strontium in the bones from ancient burials (Montgomery 2010) which will be referred to in subsequent chapters of this book.

Giles, in her recent review of the Iron Age archaeology of the Yorkshire Wolds (2007(a) 105), provides a more detailed account of the various hypotheses concerning the Arras culture than that presented here and goes so far as to write that:

Even if genetic analyses were to demonstrate links between the communities in East Yorkshire and the Champagne region, we would be left to debate the meaning of and significance of such affinities … I want to suggest that this question is a non-question; that its time has passed.

However difficult it is to answer, this question is surely too important to be dismissed; attempting to understand the cause and effects of movements and interconnections of people is one of the fundamentals of history. The classical sources, for example, provide clear accounts of Iron Age diasporas such as the Helvetii, whose migration in 58 BC from what is now southern Germany to Switzerland created severe disruption (Caesar, Gallic Wars 1:1–29), with 368,000 people, including women and children, involved. The number, according to Caesar, was written in Greek script on a list found in the Helvetian camp after their defeat. Although the necessity of treating such numbers from ancient texts with great caution is obvious, even half this amount represents a considerable population.

Caesar (Gallic Wars 4:3) also provides further corroboration of a supposed French connection with East Yorkshire, as there is an obvious resemblance of the name ‘Parisi’ to the ‘Parisii’ who are placed by Caesar as living in the area around what is now Paris.

In his famous description of Britain (Gallic Wars 5:12) he also states that:

the maritime portion (is inhabited) by those who had passed over from the country of the Belgae for the purpose of plunder and making war; almost all of whom are called by the names of those states from which being sprung they went thither, and having waged war, continued there and began to cultivate the lands.

The suitability of the term ‘tribe’ to describe the complex and disparate populations of Iron Age and Roman Britain is also worthy of some scrutiny. It has been argued (Moore 2012) that the familiar tribal model owes much to nineteenth-century notions, not always supported by archaeological evidence or classical sources and that the names of the peoples in classical accounts should be considered as reflecting the emergence of new social and political groupings in the later Iron Age. Defining precise territorial boundaries is very difficult and they are likely to have oscillated through time; a combination of natural features, especially rivers, such as the Derwent and Humber, or the North Yorkshire Moors may have served as demarcation. Concentrations of particular traits in material culture extending across what are now the modern counties of the East Riding of Yorkshire, North Yorkshire and the City of York unitary authority, seem, however, to indicate a distinctive identity in the Iron Age and Roman periods.

One of the most obvious cultural signatures for the region is the concentration of chariot burials within it. Research based principally on the typology of iron tyres from chariots also provides interesting similarities between the material culture of the Paris basin and East Yorkshire regions in addition to those outlined above (Anthoons 2007,146). In both areas the buried vehicles had flat wide tyres with no nails present, and although the detail of decoration is different, attention has been paid to the terrets (rings through which reins pass to the yoke) and in both areas there are dismantled chariots and crouched burials. The explanation given for these similarities (Anthoons 2007, 149) was the existence of elite networks linking both areas, a hypothesis which is also discussed by Cunliffe (2005). Cunliffe’s model of constant two-way contact between ‘zones of influence’ including an Eastern Zone, allowing for regional developments, provides one of the neatest explanations for obvious cultural similarities. Although Cunliffe highlights the importance of the Thames estuary, the Humber estuary deserves greater attention as there is much evidence for cultural exchange via this route extending backwards into the Bronze Age and beyond (Manby et al. 2003(b); Wright et al. 2001).

This volume aims to examine the origins of the Parisi and their relationship to the Iron Age Arras culture in the light of an enormous amount of diverse evidence, ranging from the results of the application of various scientific techniques referred to earlier such as isotope analysis on human bone (Jay and Richards 2007) to large-scale study of ancient landscapes revealed in growing crops (Stoertz 1997). It goes on to consider the impact of Rome on East Yorkshire against the background of recent interpretations of Roman Britain (e.g. Millett 1989; Mattingly 2006) and to assess human-landscape interaction within this region in the Iron Age and Roman periods, taking account of palaeo-environmental studies which have provided much new information on sea level transgression and regression, coastal and climate change, and their effects on human activity across both eras, which are again issues of great relevance today.

Apart from the seminal fieldwork and publications of Tony Brewster, Ian Stead and John Dent, and the discoveries of past antiquarians and archaeologists, whose contributions will be outlined in Chapter 1, the information presented here has been drawn from many sources, particularly the Humber Archaeology Sites and Monuments Register, the Hull and East Riding Museum, the North Yorkshire and City of York Historic Environment records and the work of a large number of colleagues who have generously shared the results of their work and who will be acknowledged below.

This is the first single authored book on Iron Age and Roman eastern Yorkshire since the publication of The Parisi by Herman Ramm (Duckworth, Peoples of Roman Britain Series) in 1978, the only other volumes being the proceedings of two conferences organised by the present author (Halkon 1989 and 1998). Since then much new knowledge has accrued due to the enormous amount of fieldwork undertaken. Much of this has been as a result of the various changes in planning regulation, requiring developers to fund archaeological investigation prior to construction. Many of these excavations are yet to be published in full and I am most grateful to colleagues from the various archaeological contractors working in this region for providing their results.

Finds of national and international significance have also been made through research projects undertaken by the voluntary sector and other bodies, especially the East Riding Archaeological Society in some cases collaborating with universities, such as those undertaken in the Foulness Valley since 1980 (Halkon 1983; 1989(b); Halkon and Millett 1999; Halkon 2003; Halkon et al. 2000; Halkon and Millett 2003; Millett 2006; Halkon 2008; Halkon et al. forthcoming), which have generally focussed on the southern part of East Yorkshire. In the north of the region two remarkable long-term landscape research projects carried out at West Heslerton (Powlesland 2003(a) and (b)) and Wharram Percy (Hayfield 1988) have continued to provide an insight into the archaeology of the Yorkshre Wolds and the Vale of Pickering in the Iron Age and Roman periods. One glance at the maps prepared by Ramm (1978) show an absence of Iron Age and Roman activity in Holderness and the Hull Valley. Research initiated by Peter Didsbury (1990) in the lower Hull Valley has totally transformed our knowledge of this much ignored area and has been followed by research projects at Arram (Wilson et al. 2006) and Baswick (Coates 2007). The Humber Wetlands project (Van de Noort and Ellis 1995, 1997, 1999, 2000; Van de Noort 2004) undertook field walking and palaeo-environmental surveys with some excavation yielding important results in the wetlands of easternYorkshire. Other dissertations and projects prepared as part of archaeology courses at Hull University such as those of Hyland in Holderness and Robinson and Coates in the Hull Valley, are particularly important in collating evidence for Roman activity.

Finds have been made by members of the public purely by chance or through metal detecting. The creation of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) has led to an enormous growth of the number of finds being reported by metal detector users and I am grateful to Dan Petts for allowing access to the PAS database.

Perhaps the most significant contribution to the extension of our knowledge of this period, especially in terms of the wider landscape, has been the National Mapping Programme undertaken by English Heritage and the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England) (RCHM (E)) before them, collating and plotting thousands of archaeological sites revealed in growing crops and captured in vertical and oblique aerial photographs. The most impressive of these covered the Yorkshire Wolds (Stoertz 1997), the well-drained soils of which are particularly sensitive to showing up archaeological features. The detailed maps of cropmarks reveal a remarkable palimpsest of settlement patterns from the Neolithic onwards, stretching from the River Humber to Flamborough Head. A similar scheme was undertaken in the Vale of York, though detailed mapping of this has not been fully published (Kershaw 2001) and mapping of the Chalk Lowland and Hull Valley by English Heritage and through the National Mapping Programme is almost completed at the time of writing. The dry summer of 2010 resulted in the appearance of many cropmark sites unknown hitherto, although it has not been possible to fully integrate this information here.

In order to provide as up to date a distribution of Iron Age and Romano-British sites and finds as possible, a new database was compiled using the sources of information listed above. I am greatly indebted to John Deverell, Richard Green, Mark Norman and Helen Woodhouse for their assistance. This database was used to generate distribution maps using Arc Map v.10 (ESRI) to provide greater understanding of the past activities of the people of Iron Age and Roman Eastern Yorkshire within their landscape.

CHAPTER 1

THE SEARCH FOR THE PARISI

BEGINNINGS

Fig. 2 Eastern Yorkshire showing the main places mentioned in the text of Chapter 1. (H. Woodhouse)

The investigation of Iron Age and Roman eastern Yorkshire began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, following the trend for antiquarian exploration elsewhere in Britain (Gaimster et al. 2007). Before that the remains of Roman buildings encountered were treated with little respect and used as a resource. According to Hull Chamberlain’s Roll No. 1, payment was made between 1321 and 1324 for the carting of stone from Brough for the refurbishment of the city defences (Corder and Richmond 1942). Roman structures were quarried for the construction of churches as a number in eastern Yorkshire contain reused Roman stone, such as Kirby Grindalythe (Buckland 1988, 295). Indeed in his appendix to Burton’s account of the discovery of the circular Roman temple at Millington, Drake remarks that: ‘it had been the custom for the inhabitants of their village, time out of mind, to dig for stones in this ground when they wanted.’ (Drake 1747, 14).

At Kirby Underdale the possible altar of Mercury (Ramm 1978, 103; Tufi 1983, no.19, Pl 4), which will be discussed in Chapter 10, had a complex history. Originally found in the 1870 refurbishment of the church, it was placed in the rectory garden before being reinstated in the church wall (Kitson Clark 1935, 95).

Although the Tudor antiquarian Leland travelled along the main roads through East Yorkshire (1540–46) which followed the routes of Roman predecessors, he makes little reference to anything other than medieval antiquities. His account, however, does provide interesting topographical observations, including a description of the Walling Fen as, ‘so large that fifty-eight villages stand in or abutting it … the fen itself … is sixteen miles around its perimeter’ (Chandler 1993, 537).

One of the earliest references to Roman coins in the region is a letter from William Strickland of Boynton Hall to Sir William Cecil in 1571, then Secretary of State to Elizabeth I, which refers to a hoard of at least sixty Roman coins dating from Vespasian to Antoninus Pius (AD 69–161), found when a house was swept away by the sea at ‘Awburn’ (Auburn) near Bridlington (Lemon 1856, 406; Kitson Clark 1935, 63). This example also provides a reminder of the vulnerability of the Holderness to coastal erosion.

It was not until William Camden (1551–1623) that the history and topography of Roman York and eastern Yorkshire was recorded in any systematic way. Camden (Holland 1610, 35) was one of the first to equate the settlements listed by Ptolemy, and other Roman documents such as the Antonine Itinerary, the Notitia Dignitatum and Ravenna Cosmography (Ramm 1978; Rivet and Smith 1979), with towns within the East Riding of his day: ‘Under the Roman Empire, not farre from the banke, by Foulnesse a River of small account, where Wighton, a little Towne of Husbandry well inhabited is now seen stood, as we may well thinke in old time Delgovitia.’

The debate about the location of Delgovitia and other places mentioned in these documents is still ongoing (Creighton 1988; Millett 2006) and will be addressed later in this book.

In 1699, Abraham De La Pryme (1671–1704), Curate of Holy Trinity church in Hull (Jackson 1870, 200), without knowing the full implications of his observation, noted the following in his diary: ‘I saw on my journey to York many hundreds of tumuli which I take to be Roman at a place called Arras on this side Wighton not mentioned in any author description thereof which I intend to digg into…’

De La Pryme’s enthusiasm for the study of the past is beyond doubt, expressed in this extract of a letter to Dr Gale, Dean of York: ‘Thank you for your encouraging me to prosecute these studdys, than which nothing is more sweet, nothing more pleasant to me … I do already find that there are a great many old antiquitys monuments and inscriptions … in many parts of this country’ (Jackson 1870, 200).

De La Pryme never did carry out this intention and it was not until 1815–17 that the mounds at Arras were opened by Stillingfleet, Hull and Clarkson and found to be Iron Age in date, an event which will be discussed in more detail below.

De La Pryme was also the first to recognise the significance of Roman antiquities at Brough-on-Humber (Jackson 1870, 219). Another antiquarian, Horsley, also described the ramparts and foundations of Roman Brough and their setting, observing that ‘The Humber formerly came just up to it, and it still does at high spring tides’ (Horsley 1732, 314 and 374).

In the late 1970s Peter Armstrong (pers. comm.) recognised curves of ancient shorelines, fossilised within field boundaries to the west of Brough. Herman Ramm (1978, 111) also noted the changes that had taken place in the shape of the Humber shore in the Walling Fen area based on eighteenth-century maps. It was not until the research of the present author that the full significance of Horsley’s remark was recognised (Halkon 1987; 2008; Halkon and Millett 1999). From study of soil maps (King and Bradley 1987) it was realised that Roman Brough was at the edge of the tidal inlet into which the Foulness flowed, later becoming the Walling Fen, described by Leland. This observation also provided a context for the inscribed Roman lead pigs found in this vicinity, traded from Derbyshire through the Humber estuary, which were first recorded in the later eighteenth century (Gough 1789; Kitson Clark 1935).

Horsley’s contemporary, the great York antiquarian Francis Drake, disputed the former’s equation of Brough with Petuaria in his attempt to place the Roman settlement names of East Yorkshire (Drake 1736) and to trace the routes of the Roman roads around York (Plate 1). At Barmby Moor, Drake (1736, 63) cites the perceptive observation of Dr Martin Lister, made around 1700, one of the first recorded ‘scientific’ fabric descriptions of the pottery which he found there, rightly presuming it to be Roman:

There are found in York in the road or Roman Street out of Micklegate and likewise by the river side … urns of three different tempers viz. -1. Urns of a blewish gray colour having a great quantity of coarse sand wrought in with the clay 2. Others of the same colour being either a very fine sand mixed with it full of mica or ‘cat silver’ or made of clay naturally sandy … The composition of the first kind of pot did first give me occasion to discover the place where they were made. The one about midway between Wilberfoss and Barmby on the Moor … in the sand hills on rising ground where the warren now is – where I have found scattered widely up and down, broken pieces of rims, slag and cinders. (Lister 1681–2, in Hutton et al. 1809, 518).

The pottery described is very similar to that produced at Holme-on-Spalding Moor (Halkon and Millett 1999), and the ‘sand hills on rising ground’ are very like the location of most of the Roman settlements and kiln sites around Holme.

Drake (1736, 33) adds that: ‘It is to be observed that the present road to York goes through this bed of sand, cinders &c [etc] but the Roman way lies as I suppose a little on the right of it.’

One of the first Roman mosaics to be found in the East Riding was ploughed up at Bishop Burton near Beverley (Thoresby 1715, 558) and described in more detail by Gent (1733, 77) as being of red, white and blue stones (see Chapter 8). It is only recently that the precise find spot has been located (Williamson 1987). In the north of possible Parisi territory, the Roman forts near Pickering, usually known as Cawthorn camps were first noted by Robinson in a letter to Gale in 1724, which subsequently became the focus of much later research.

To the west of the Wolds, near the source of the River Foulness at Londesborough, Drake (1736, 32) reported the discovery of a Roman road during the construction of the Great Pond, one of a series of lakes and canals created by Knowlton, the chief gardener to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork (1694–1753) at Londesborough Park. Burlington, a great patron of the arts, must take credit for supporting this important burst of activity (Henrey 1986, 78).

The discovery of the road renewed the efforts of antiquarians to locate the Roman settlements listed by classical authors, for Drake was in correspondence with the Revd William Stukeley, the doyen of English Antiquarians of the time, concerning his discoveries. Stukeley visited ‘Lonsburrow’ and Goodmanham on 1 July 1740 and the newly discovered Roman road was exposed for him to examine (Lukis 1887, 386). Lord Burlington commissioned John Haynes of York to draw a map showing the route of the Roman road through his estate and beyond. The document, dated 1744, was entitled ‘An accurate survey of some stupendous remains of Roman antiquity on the Wolds in Yorkshire … through which some grand military ways to several eminent stations are traced’ (Henrey 1986, 205) and it is a testament to Haynes’ map-making skills that it was possible to correlate the buildings illustrated in his map to those revealed in recent survey work (Halkon et al. 2003; Halkon 2008, 198).

In a letter to Mark Catesby read at a meeting of the Royal Society on 6 March 1745–46, Thomas Knowlton described the discovery (Philosophical Transactions Royal Society, March/April 1746, 100):

Many foundations (were found) in a ploughed field … discovered by one Mr Hudson, a farmer at Millington, as he formerly tended his sheep on one side of the hill, and on the opposite side had perceived in the corn a different colour for some years before: which led him this summer to dig … there were many other foundations which had Roman pavements within them … by which I imagine after the dissolution of the temple became a Roman station, then called Delgovicia, which has been so uncertainly fixed at Goodmanham, Londesborough, Hayton &c.[etc].

This extract is particularly interesting because it is one of the earliest references from the East Riding to cropmarks being used for the recognition of archaeological features. It is also a reminder that Hayton, which has been the focus of recent fieldwork (Halkon and Millett 2003; Halkon et al. forthcoming), was even at this date perceived to be a possible location for a Roman settlement of some significance.

The discovery of the Millington remains caused some excitement as Drake and his colleague John Burton (Burton 1745; 1753) carried out survey work there as well. Ramm (1990) highlights some contradictions between the accounts of Knowlton and the other two writers, though Burton and Drake both endorsed Knowlton’s conclusion that Millington was Delgovicia. In the manuscript version, Drake points out an interesting hazard to archaeological survey at this time:

Whilst we were on the spot directing the survey, in the year 1745, a year in which the House of Stewart again did attempt to recover the British Crown, some people observing us, gave an information at York, that we were marking out a camp in the Wolds; which had like to cause us some trouble to contradict. (Drake 1746, cited in Ramm 1990, 13).

The remains at Millington and the location of Delgovicia will be discussed below, but the impact of these discoveries remained in local memory for some time afterwards as they are reported in the diary of John Wesley:

Mon. July 1, 1776. I preached at about eleven to a numerous and serious congregation at Pocklington. In my way from hence to Malton, Mr C- (a man of some sense and veracity) gave me the following account: his grandfather Mr H-, he said about twenty years ago, ploughing up a field, two or three miles from Pocklington, turned up a large stone, under which he perceived there was a hollow. Digging on he found at a small distance, a large magnificent house. He cleared away the earth; and going in to it, found many spacious rooms. The floors of the lower storey were of mosaic work, exquisitely wrought. Mr C- himself counted sixteen stones within an inch square. Many flocked to see it from various parts, as long as it stood open, but after some days, Mr P- (he knew not why) ordered it to be covered again and he would never suffer any to open it, but ploughed the field all over. (Curnock 1938, 113).

Surprisingly Drake paid little attention to Malton, the main Roman centre in the north of the territory of the Parisi, other than noting the presence of its fortifications (Kitson Clark 1935, 99). He was, however, involved with the discovery and exhibition to the Royal Society in 1755 of the tombstone inscription to Macrinus, a cavalryman in the imperial bodyguard found there which will be discussed more fully in Chapter 6 (RIB 714; Kitson Clark 1935, 100). John Walker, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, lived in Malton and noted some finds. He corresponded with Thomas Hinderwell who copied much material into a 1798 edition of his History of Scarborough (Hinderwell 1798). It is thanks to this remarkable book that so much information about Roman Malton and district is preserved. The Malton Messenger newspaper also provided detailed accounts of discoveries, many of them reported by the antiquarians Captain Copperthwaite, George Pycock and Charles Monkman during the period of rapid development which followed the arrival of the railways from the 1860s onwards (Kitson Clark 1935). The foundations were therefore laid for the important fieldwork around Malton undertaken in the 1920s to 1940s by the Roman Malton and District Committee of which Philip Corder, John L. Kirk and the Revd Thomas Romans were the luminaries. Their work, which expanded to include other areas of North and East Yorkshire, became the main archaeological effort in the region between the nineteenth-century barrow diggers and the excavations backed by the Ministry of Works in the 1960s and later. The contribution of this group will be considered more closely in the next section.

As far as the Iron Age is concerned, the first recorded excavations of square barrows in East Yorkshire were at Danes Graves near Kilham in 1721 (Stead 1979,16) when several mounds were dug into after they were observed by a group who were beating the bounds of the parish, an event which was recorded in a parish register. Antiquarian exploration resumed at Arras from 1815 to 1817, where Barnard Clarkson, of Holme House, Holme-on-Spalding Moor, the Revd Edward Stillingfleet, vicar of South Cave and an active antiquarian, with Dr Thomas Hull of Beverley, supervised the excavation of many of the barrows, which had been noted by De La Pryme. They identified the burials as being of ‘Ancient British’ origin, the discovery of several chariot burials causing Stillingfleet (1846) to equate them to classical descriptions of chariot-fighting Britons. It is important to note that the so-called ‘King’s Barrow’ and ‘Queen’s Barrow’ are described as being circular.

The only contemporary account of the find is a manuscript plan drawn up by William Watson, a mapmaker of Seaton Ross, which is dated August 1816 (Stead 1979, Plate 1, 109). The first published reference appears in Oliver’s History of Beverley (Oliver 1829), which includes a letter from Thomas Hull to the Scarborough antiquarian Hinderwell. A fuller account was given by Stillingfleet (1846), published thirty years after the discovery. Presumably inspired by the publication of the above, the Yorkshire Antiquarian club carried out further excavation at Arras in 1850 (Proctor 1855; Davis and Thurnam 1865; Stead 1979), as well as on the contrasting lowland square barrow cemetery at Skipwith Common (Stead 1979).

The indefatigable Canon Greenwell excavated further Iron Age burials, some furnished with chariots at Arras and Beverley (Greenwell and Rolleston 1877; Greenwell 1906, Kinnes and Longworth 1985, 142, PL un. 64), and finally aged seventy-seven, with his old arch rival Mortimer (then aged seventy-two) at Danes Graves, in 1897–98, with the comparatively youthful drainage commissioner and antiquary Thomas Boynton FSA of Bridlington, aged sixty-five (Fig. 3a, b, c).

The details of these and later excavations are described by Stead (1979) and will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Apart from the route of the Roman roads and the location of named Roman settlements, the focus of antiquarians, especially on the Yorkshire Wolds, had been on burials, which they hoped would supply artefacts for their collections. However, Stillingfleet (1846) made some observations about the landscape of the area around the Arras cemetery. He was one of the first to suggest that the nearby ‘Double Dykes’ were contemporary with the burials, and similar to the linear earthworks of the North Yorkshire Moors, studied by Spratt (1981; 1989). Drake and Burton had mapped the entrenchments around the temple site at Millington, wrongly attributing them to the Romans, assuming that they were part of the ‘Roman Station’ of Delgovitia. Some antiquarians had confused the linear earthworks with roads, an error highlighted by the Revd Maule Cole (1899), who published the first systematic account of the roads since Drake. This survey is of particular importance, for according to Kitson Clark (1935, 33), the Ordnance Survey maps at 6 inches to the mile were based on his paper.

The most important work on the so-called ‘British entrenchments’, which travel long distances across the Yorkshire Wolds and will be discussed below, was by John Robert Mortimer (Giles 2006; Harrison, 2011), a Driffield-based corn-merchant whose Forty years Researches… remains one of the most important books to have been written on the archaeology of East Yorkshire (Mortimer 1905, 381–385). The linear earthworks were almost the only non-sepulchral monuments to receive attention (Plate 3). Mortimer (1905, lxxxii) expressed his disappointment in not finding more Roman remains, although he did find pottery and other material in enclosure ditches at Blealands Nook, as well as several corn driers, or malting ovens which he wrongly identified as hypocausts. He also misidentified the important Iron Age burial accompanied by fine swords at North Grimston in 1902 as Roman, although he recorded and illustrated the finds with his usual thoroughness.

Fig. 3a Boynton, Mortimer and Greenwell excavating at Danes Graves, 1898.

Fig. 3b Drawing of the Danes Graves chariot burial. (Mortimer 1905, 359)

Fig. 3c Copper-alloy pin decorated with coral from Danes Graves, now in the Yorkshire Museum, York. (Mortimer 1905, 364)

Roman coins were one of the most frequent discoveries made by nineteenth-century antiquarians such as those found ‘… about 25 chains (500m) north-east of Ludhill Spring, Hunger Hill closes’, near Nunburnholme (Kitson Clark 1935, 136) reported on by the great Victorian antiquarian and landowner Lord Albert Conyngham (Denison) 1st Baron Londesborough (1806–1860). Less than half a kilometre away and possibly related, a very large hoard of coins was found in a pot at Methill Hall, Nunburnholme, which consisted of at least 3,000 coins (Kitson Clark 1935, 136). These were presented by Lord Londesborough to the museums of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society and Leeds Literary and Philosophical Society. Further Roman activity was found at Nunburnholme by the Revd M.C.F. Morris (1907), whilst attempting to locate the nunnery. He excavated the foundations of a Roman building with pottery and a coin of the Emperor Caracalla (AD 211–217).

The Nunburnholme discoveries provide an example of continued antiquarian interest on the Yorkshire Wolds. Its practitioners, who were largely clerics or gentry, present a microcosm of developments elsewhere in Britain. Most discoveries were sporadic chance finds made during agricultural activities or as a result of the development of the region’s infrastructure. At Rosehill, Goodmanham, for example, a Roman site was found in 1888, during the construction of a railway cutting and viaduct. Here ‘A quantity of Roman pottery was disinterred from the surface soil consisting of … samian ware; thin smooth light grey … and coarse black pottery with particles of Chalk in it. Some beads, ornaments of jet, iron spearheads and Roman coins were also found’ (Maule Cole 1899, 44), discoveries followed up by the present author.

Away from the Yorkshire Wolds, on the lowlands of the Vale of York, more Roman finds were reported. In 1853, the Revd R. Whytehead gave a number of Roman urns to the museum of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society in York discovered at Holme-on-Spalding Moor (Yorkshire Philsophical Society Annual Report 1853). Roman pottery is also recorded from Tollingham, in the same parish, in 1873, where a Roman lead coffin was also found, displayed outside the vicarage as an ornamental trough and subsequently stolen! (Yorkshire Weekly Post, 14 January 1899.)

FROM ANTIQUARIAN TO ARCHAEOLOGIST

A key figure in the development of a more systematic and academic approach to archaeological rather than antiquarian investigation was Thomas Sheppard, appointed Curator at Hull Museums in 1901 and Director 1921–41, who himself had been introduced to prehistory by Mortimer (Schadla-Hall 1989; Sitch 1993). There is insufficient space here to discuss Sheppard’s major contribution in any detail. In terms of Roman archaeology, Sheppard collaborated with Philip Corder, schoolmaster at Bootham School, York, who eventually became Assistant Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of London and President of the Royal Archaeological Institute. Corder was keen to find opportunities to excavate Roman pottery production sites to provide comparisons with those he had excavated at Crambeck, near Castle Howard (Corder 1928) and so Sheppard and Corder decided to follow up earlier references concerning Roman pottery at Holme-on-Spalding Moor. Sheppard describes his first visit to Throlam as follows:

There, in a large field arising out of a flat peaty area, was ‘Pot Hill’ … We picked up as many pieces of earthenware rims, bases, and handles as we could carry. The hill was 100ft across and 6ft high and said to be a solid mass of pottery fragments. On seeing the mound I felt like repeating what the American said when he first saw a giraffe, ‘I don’t believe it!’ (Sheppard 1932, 3).

In May 1930, Corder, together with Dr J.L. Kirk and two ‘trained men’ from Malton, excavated several kilns there (Corder 1930(a), 6) and Sheppard provides the following account of the first day’s work:

Subsequently … with the aid of a large double-decker bus lent by the Hull Corporation, a party of the Hull Grammar School boys interested in historical work was conveyed to Pot Hill and carried with them a score of spades, shovels and pickaxes, supplied by the city engineer, and some new large tin drums lent by Mr Douglas of the Hull Corporation Sanitary Department. A full day was spent and something like 12cwt of pottery was brought away as a result of the day’s digging. (Sheppard in Corder 1930(a), 7)

This excavation was of considerable significance as it identified the source of much of the greyware pottery, ubiquitous on Roman sites in East Yorkshire, which received the generic term ‘Throlam Ware’. This name persisted until recently when it was realised that there were many more kilns in the Holme-on-Spalding Moor area (Halkon 1983; Halkon 1987; Halkon 2003; 2008; Halkon and Millett 1999). At the end of his report, Corder stated that knowledge of the history of the fort at Brough might provide a solution to the problem of dating the pottery (Corder 1930(a)). This comment is important as it showed the existence of a research strategy aimed at understanding the Roman sites of this part of East Yorkshire as a coherent entity.

Further opportunities were provided by the foundation of Hull University College, whose Local History Committee instigated a five-year programme of excavation from 1934 at Brough-on-Humber (Wright 1990) co-directed by Corder with the Revd Thomas Romans (Corder 1934; Corder and Romans 1935, 1936, 1937). The work was undertaken with a small team of paid excavators led by Bertie Gott and a number of volunteers, including E.V. (Ted) and C.W. Wright, who would later discover the Bronze Age Ferriby boats, and Mary Kitson Clark, who compiled ‘A Gazetteer of Roman Remains in East Yorkshire’ (1935) which remains a fundamental resource (Fig. 5).

Digging took place over a month-long summer season, and the quality of work was certainly the best that had so far been carried out. The main results of the five years of the Brough Excavation Committee’s research were the confirmation of the presence of a conquest period fort, a later fort and civilian settlement complete with a theatre, suggested by the discovery of the inscription recording the presentation of a new stage (RIB 707) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4 Excavation at Pot Hill, Throlam, May 1930. Bertie Gott cuts a trench through the buried dump of Romano-British pottery ‘wasters’. (Corder 1930)

Fig. 5 The ‘staff’ at Brough, 22 August 1936. Standing, right to left: Philip Corder, Thomas Romans Jnr (son of co-director the Revd Thomas Romans who probably took the photograph), Bertie Gott, R. Gilyard-Beer. Seated, right to left: Mary Kitson-Clark, Joan Southan, Richard Harland (identified by Richard Harland). (Hull and East Riding Museum: Hull Museums)

As a spin-off from the above, Corder also published the discovery of a Roman cemetery next to the Roman road running towards South Cave, which was found in 1936. The most spectacular find here was a male skeleton accompanied by a wooden bucket, hooped in iron, and the remains of two iron sceptres, decorated with helmeted bronze heads which will be discussed in Chapter 10 (Corder and Richmond 1938).

Corder’s work at Brough was not followed up until 1958–61, when John Wacher, under the auspices of the Ministry of Works (Wacher 1969) resumed excavation there as part of the growing ‘professionalisation’ of archaeology in the region. Wacher (1995) reassessed his excavations subsequently and the town has been subject to large-scale redevelopment, preceded by rescue excavation and evaluation. These interventions have been summarised by Wilson (2003). In 1977, at Cave Road, Brough, Peter Armstrong with the East Riding Archaeological Society (ERAS) excavated a stone enclosure and roadway overlying first century AD ditches, lying close to the Walling Fen inlet, though the site has not been published. In 1980, at Petuaria Close, to the north of Welton Road, ERAS undertook rescue excavations, which revealed occupation of the late first and early second centuries AD, including a possible military oven and ‘ill-defined’ post structures (Armstrong 1981, 6). The footings of a very substantial later Roman limestone wall were also found which, according to Armstrong, may be part of the later town defences. Welton Road was also the focus for an evaluation in 1991 by the Humberside Archaeological Unit uncovering a road and associated features. This was followed up in 1994 by the York Archaeological Trust, who excavated further Roman buildings in plots positioned along the Roman road with associated fields, discovering a T-shaped malting oven or corn drier, cremation and inhumation burials and animal burials (Hunter-Mann et al. 2000).

Fig. 6 The Brough theatre inscription as found, just to the west of Building 1 in Bozzes Field during the 1937 excavation by Bertie Gott, Corder’s foreman. (Hull and East Riding Museum: Hull Museums)

Further along the Roman road at North Newbald, M.W. Barley and Corder also carried out an excavation of a Roman villa in 1939, which was furnished with mosaics and painted wall plaster (Corder 1941). Work here was continued by Mr D. Brooks of ERAS in the 1960s but remains unpublished. A further villa was found at Rudston in 1933, when a Mr Robson of Breeze Farm ploughed up tesserae in a field near the parish boundary with Kilham (Stead 1980) which turned out to be from mosaics including one portraying Venus, which remains iconic in the archaeology of Roman Britain and will be the subject of further discussion. Later excavations by Stead during the removal of the Venus mosaic from the sheds which had been erected to protect it from the elements to Hull Museums resulted in the discovery of the spectacular ‘Charioteer’ mosaic in 1971. Stead also carried out some excavation on the extensive Roman villa at Brantingham in 1961–62 (Stead et al. 1973). The site had been discovered in 1941 during quarrying and a mosaic pavement and other artefacts were recovered in 1948 and taken to Hull Museum. A fine geometric mosaic was stolen under mysterious circumstances, but had fortunately been carefully photographed in situ (Neal and Cosh 2002, 325). The location of the Brantingham complex and its relationship to nearby Brough will be discussed later.

By the 1930s, E.V. and C.W. Wright began to explore the Humber foreshore near their home at North Ferriby, under the guidance of Corder, an activity which was to have important implications for the study of Iron Age East Yorkshire as a whole. They recovered late Iron Age imported wheel-made pottery (Corder et al. 1939; Wright 1990). A trial excavation was also carried out there, in which more pottery and brooches were found, but little structural evidence. Corder (Corder and Davies Pryce 1938) suggested that the site was a native trading station doing business with the Roman world. As with Brough, there was to be a long gap before further fieldwork was undertaken on this most important site. This subsequent work was largely the result of the continued enthusiasm of Ted Wright and vigilance of Peter Didsbury (Crowther and Didsbury 1988), who continued to examine the eroding cliff. Excavations at Redcliff followed, taking place between 1986 and 1988 (Crowther et al. 1990).

Apart from the work at Redcliff and the activities of Greenwell and Mortimer, little attention had been paid to the Iron Age since the excavation of Stillingfleet and his colleagues (Stillingfleet 1846). In 1836 labourers cleaning out a ditch at Roos Carr, near Withernsea came across one of East Yorkshire’s most celebrated finds, the Roos Carr figures, along with other wooden objects (Plate 2) (Poulson 1841, 100; Sheppard 1902; 1903). Five male figures survive although Poulson recorded eight. Some of the figures bore round shields and there may have been two boats, one animal head carved from yew, with various other wooden articles ‘too much decayed to remove’. The eyes of some of the figures consisted of quartzite pebbles. The figures, which have been conserved and redisplayed, have been radiocarbon dated to Cal BC 770–409 (1 sigma) Cal BC 800–400 (2 sigma) (Dent 2010, 101) and are therefore of early Iron Age date. Much has been written about the Roos Carr figures which most perceive as objects of ritual deposition (Coles 1996; Aldhouse-Green 2004).

At Bugthorpe, a single sword in a sheath was discovered during land drainage (Wood 1860). Thurnham (1871) and Greenwell and Rolleston (1877) refer to a body being found with an iron sword in a bronze sheath and an enamelled bronze brooch here (Stead 1979) and there is some doubt as to whether the two swords from Bugthorpe are the same. Although Stead’s main concern is the presence or absence of a barrow mound, he does mention the possibility that there were in fact two swords. It may be that the sword that Wood referred to was a votive offering in a ‘watery place’ (Bradley 1990) as the fact that it was found whilst draining implies that the ground was wet.

A further Iron Age ‘warrior burial’ and three burials without grave goods were found 6km away at Grimthorpe in a chalk-pit (Plate 3) (Mortimer 1905, 150–52, Stead 1979, 37) in the contrasting landscape of the Wolds. This discovery was partly the inspiration for Stead’s excavation in 1962 of the nearby hill fort at Grimthorpe (Stead 1968), one of the few excavations of an Iron Age settlement on the western escarpment of the Yorkshire Wolds. The landscape context of Grimthorpe will be discussed below. Recent re-calibrated C14 dates (Dent 1995; 2010, 100), however, make it unlikely that the warrior burial was contemporary with the construction of the hill fort and may not have occurred even during its occupation. Stead’s main interest at this stage was, however, in the burials of the Arras culture, and he returned to the type-site to carry out further excavation and a geophysical survey in 1959 (Stead 1979) with inconclusive results.