13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

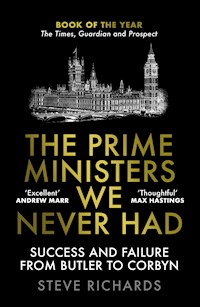

BOOK OF THE YEAR, The Times, Guardian and Prospect Was Harold Wilson a bigger figure than Denis Healey? Was John Major more 'prime ministerial' than Michael Heseltine? Would David Miliband have become prime minister if it were not for his brother Ed? Would Ed have become prime minister if it were not for David? How close did Jeremy Corbyn come to being prime minister? In this piercing and original study, journalist and commentator Steve Richards looks at eleven prime ministers we never had, examining what made each of these illustrious figures unique and why they failed to make the final leap to the very top. Combining astute insights into the demands of leadership with compelling historical analysis, this fascinating exploration of failure and success sheds new light on some of the most compelling characters in British public life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

THE PRIME MINISTERSWE NEVER HAD

‘Prime ministerial politics is a rare example of a field in which the losers are often more interesting and more impressive than the eventual winners. Steve Richards deserves applause for noticing this, and exploiting it with great empathy and close argument in this excellent book. He is one of the shrewdest political commentators we have; and unusual in apparently liking politicians.’

Andrew Marr

‘Britain’s unusually capricious system of selecting its prime ministers means some very gifted leaders have been left on the shelf. There is no one better qualified than Steve Richards to blow away the cobwebs, and to tell us which of them might have made better prime ministers than the rum lot we sometimes got.’

Anthony Seldon

‘This is another insightful and entertaining work from Steve Richards, who remains among the brightest and best of British writers and broadcasters.’

Nick Timothy

‘A story of slamming doors and sliding doors. Terrific insights on the great prime ministers we didn’t have from one of the shrewdest political commentators we’re lucky to have.’

Jon Sopel

‘A compelling account of the nearly men and women of Number Ten. Steve Richards is a must-read writer on politics, with the rare talent of being both fun and informative.’

John Crace

Steve Richards is a political columnist, journalist, author and presenter. He regularly presents The Week in Westminster on BBC Radio 4 and has presented BBC radio series on Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron and Theresa May. He also presented the BBC TV programmes Leadership Reflections: The Modern Prime Ministers and Reflections: The Prime Ministers We Never Had. He has written for several national newspapers, including the Guardian, the Independent and the Financial Times. He also presents a popular political one-man show each year at the Edinburgh Festival and across the UK. His last book was The Prime Ministers: Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to Johnson.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Steve Richards, 2021

The moral right of Steve Richards to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The picture credits on p. 307 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 241 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 243 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Rab Butler

2. Roy Jenkins

3. Barbara Castle

4. Denis Healey

5. Neil Kinnock

6. Michael Heseltine

7. Michael Portillo

8. Ken Clarke

9. David and Ed Miliband

10. Jeremy Corbyn

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Notes

Picture credits

Index

To my parents, Keith and Val.

INTRODUCTION

Compare a list of modern prime ministers with the names of the prime ministers we never had. Why did one group succeed where the other failed? Was Harold Wilson a bigger figure than Denis Healey? Was John Major more prime ministerial than Michael Heseltine? Why did Edward Heath reach Number Ten while the more deft and experienced Rab Butler failed to do so in spite of making several attempts?

In drawing up the list of prime ministers we never had in the following pages, I apply two simple qualifications. Those included must have been regarded at some point in their careers as a likely or probable prime minister. As well as being viewed in this flattering light, they must also have had a serious chance of making the leap. The feasible opportunity is as important as the perception of greatness to come.

In my last book on modern prime ministers there could be no dispute as to who was included. Starting with Harold Wilson, each one of them walked into Number Ten and ruled with varying degrees of fragility. No reader could ask why Edward Heath or James Callaghan were part of the sequence. They were prime ministers. The theme of this book, however, is not quite so definitive.

To take an example, some might point out that Neil Kinnock and Jeremy Corbyn lost two elections and Ed Miliband lost one. They all feature in the coming pages. How could they qualify when they lost elections by significant margins? The answer is straightforward. All three were leaders of the Opposition who were regarded as possible winners of future elections. Kinnock was favourite to win the 1992 election, or at least be prime minister in a hung parliament. Miliband was perceived similarly in the build-up to the 2015 general election. Indeed, Miliband spent the evening on election day with advisers compiling his first government, a sad novelistic image in the light of what was to follow a few hours later. Corbyn was not so methodical, but after wiping out the Conservatives’ majority and considerably increasing Labour’s vote in the 2017 election he was briefly and justifiably viewed as a possible prime minister – even if, at times, he struggled to see himself in such a light.

Nearly all the others included in this book did not lead their parties, despite it seemingly being a fundamental precondition for becoming prime minister. Roy Jenkins was the SDP’s first leader but never led the Labour Party, although it was as a Labour Cabinet minister that Jenkins was first seen as a potential prime minister. The other non-leaders included were seen for long phases of their careers, or in some cases more fleetingly, as likely party leaders and prime ministers. In some cases, every word uttered at key phases in their careers was seen through the prism of a leadership bid. For a time, the likes of Michael Heseltine, Michael Portillo and David Miliband could not cross a road without prompting analysis of how the manoeuvre would impact on their ambition to become prime minister.

Part of the mystery I seek to solve is that some of the prime ministers we never had were better qualified than those who got the top job. A few had the qualities to be big change-makers too: strong personalities tested by challenges, and possessing the capacity to convey their mission with an accessible flourish. Roy Jenkins, Michael Heseltine, Denis Healey, Ken Clarke and Rab Butler were authoritative as public figures and quickly acquired deep ministerial range. Healey, Clarke, Jenkins and Butler were chancellors at times when the economy wobbled precariously, while Heseltine’s ministerial challenges included replacing the widely loathed poll tax and reviving some run-down inner cities – the latter being not the most fashionable crusade at the height of Thatcherism in the early 1980s.

Heseltine was never chancellor, although the characters in this book show that occupying that role is not necessarily a route to becoming prime minister anyway. In modern times, only John Major and Gordon Brown moved directly from Number Eleven to Number Ten. James Callaghan had also been chancellor, though much earlier in his career. He was Foreign Secretary immediately before moving into Number Ten. Chancellors are often seen as future prime ministers, yet they rarely make it to the very top.

Healey was chancellor for more than five years in the wildly turbulent 1970s, a feat of endurance to say the least. He emerged as a substantial figure and a TV celebrity, a triumph given that he had taken a range of deeply unpopular decisions. As chancellor, Ken Clarke guided the UK economy to a position of reasonable strength by 1997, while being as exuberant a performer as Healey and Heseltine in the media and the conference hall. After the Conservatives’ 1997 election defeat, Clarke topped the opinion polls as the most popular candidate in the party’s leadership contest. He did so again during the leadership contests he fought in 2001 and 2005. He never won.

As well as being chancellor, Rab Butler was a radically reforming Education Secretary, a modernizing party chairman and a thoughtful Home Secretary. When Conservative prime ministers he served under were ill, Butler stood in. He never acquired the crown.

Roy Jenkins was another chancellor who never became prime minister. He was almost as well qualified as Butler: a reforming Home Secretary, a chancellor who steadied the boat after Labour had been forced to devalue the pound, and a president of the European Commission who returned from Brussels to help launch a new force in British politics, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) – which, for a time, appeared to be sweeping away all before it. Jenkins was also a brilliant biographer, mainly of those who did manage to become prime minister. He had devoted followers in the Labour Party and then in the SDP. When Harold Wilson became paranoid about threats to his leadership he was especially neurotic about Jenkins, a figure who some in his party and much of the media regarded as incomparably more substantial than the Labour leader. But it was Wilson who won four elections; Jenkins never became prime minister. This book explores the reasons why.

When John Major felt increasingly fragile as prime minister, he worried about the threat posed by Heseltine and Clarke. Yet they were largely loyal to him. The one he had most cause to worry about was Michael Portillo, adored by Margaret Thatcher and her followers, a figure with serious ambition and charisma. In the mid-1990s, Portillo was seen as Thatcher’s heir and the successor to Major. Yet before long Portillo was not even an MP anymore, and he discovered that his passion for power had faded to the point where the flame hardly flickered at all.

While Gordon Brown was still prime minister, some Labour MPs urged David Miliband, then Foreign Secretary, to launch a challenge. Miliband was Labour’s equivalent to Portillo in some respects. He considered making a move against Brown, and there was much talk in parts of the Labour Party and the media of Miliband launching a successful leadership challenge. In the end he did not act. A few years later, in the 2010 leadership contest, David began as favourite to win but was defeated by his younger brother, Ed. Some in the Labour Party and the media still regard David as the lost leader, the one that would have led his party back to power. Nonetheless, if David had become leader there probably would have been a thousand columns and knowing judgements asserting that the party had elected the wrong brother. Perceptions of leaders are fickle and can quickly change.

There is a single chapter on the Miliband brothers, as their tense, discordant dances towards the crown were staged more or less at the same time. They had similarities, unsurprisingly, and yet were far apart ideologically. Both contributed to the fall of the other. Both were decent and thoughtful. Yet they form a dark chapter – two brothers who became ambitious, or perhaps had ambition thrust upon them, and who did not fulfil their desire to reach the top.

There is only one woman on this list and she only just met the criteria, a sad reflection on the male-dominated world of British politics, especially Labour Party politics. Potential female prime ministers in the Conservative Party became prime minister. Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May would have qualified for this book if they had not secured the superior qualification of moving into Number Ten. In the Labour Party there is a case for Margaret Beckett and Harriet Harman. Both might have been formidable prime ministers, but neither went through a phase when they were considered as likely candidates. To her regret, Harman never stood for the leadership, and she acquiesced when Gordon Brown did not make her deputy prime minister after she had won the deputy leadership contest in 2007, a considerable triumph in a strong field of candidates. If she had insisted on being made deputy prime minister or had stood and won the 2010 leadership contest, she may have become a prime minister or another that we never had. She did not do so.

Margaret Beckett held a range of Cabinet posts including Foreign Secretary, and was also acting leader when John Smith died in 1994. She was a formidable voice when Labour was in power and when it struggled in opposition after the 2010 election – always authoritative, and more experienced than most of her colleagues who flourished in the New Labour era. Beckett had been a minister in the 1970s, and was on the left as the party erupted into civil war after the 1979 election defeat. Such was her range and depth that she had the capacity to contextualize and weigh up significance as apparent crises erupted most hours of each day. A calm perspective is a rarity in the frenzy of modern politics.

Her only realistic chance of becoming a potential prime minister was if she had won the 1994 leadership contest. However, Tony Blair was the victor by a big margin; he’d been seen as the winner from the moment he announced his candidacy. Famously, the only question in the summer of 1994 was whether it should be Blair or Brown. Rightly or wrongly, even at the height of their careers, neither Harman nor Beckett were spoken of as potential prime ministers. Harman never saw herself in that role. Beckett dared to hope that her role might be permanent when she became temporary leader. When Blair entered the race, her hope vanished.

Barbara Castle is included in this book. She did not envisage becoming prime minister either, although she was flattered to be described sometimes as the politician who might be ‘the first woman prime minister’. Like Harman, she did not stand in a single contest to be leader. Castle makes the list on the basis that for a short time she was the most prominent woman in British politics, and was seen by her admirers in the Labour Party and the media as a potential prime minister.

Quite a lot of the perceptions are retrospective in her case. During Labour’s 2020 leadership contest the candidates were asked regularly for their favourite past Labour leaders. The response of Lisa Nandy when taking part in a Channel Four debate was for a non-leader: ‘Barbara Castle was the best PM Labour never had.’ In a leadership contest, every utterance is picked apart; this was a subtle response, avoiding the dangerous symbolism of backing an actual leader from the past. Nandy’s choice also showed that Castle’s legacy had endured. The former Labour Cabinet minister Patricia Hewitt spoke similarly a few years earlier: ‘Barbara Castle should have been Labour’s – and Britain’s – first female prime minister. What a role model she would have been: passionate, fiery and absolutely committed to social justice.’1 Indeed, while reflecting on her own career, Margaret Beckett also made the case for Castle being the Labour prime minister we never had.2

Castle had many of the qualities required for leadership: burning convictions, charm, energy, and the ability to communicate the reasons for her beliefs to an audience that might not automatically share them. She also had a skill for forming genuine friendships with some of the biggest figures, always helpful when riding towards the top. Harold Wilson admired and liked Castle. She greatly respected him, observing often that if Wilson had stayed on as prime minister instead of resigning in 1976, Labour would have won in 1979.

Castle did not become the UK’s first woman prime minister. Margaret Thatcher got there in 1979. In the mid-1970s, Castle noted in her diary that her fellow Cabinet minister, Shirley Williams, had become Wilson’s favourite: ‘Harold is singling out Shirley for special and repeated praise… The newspaper stories about her becoming prime minister are increasing.’3 But, like Castle, Williams never thought she would acquire the crown: ‘I was excited that people were saying it, but I never took that PM stuff very seriously. I knew it wasn’t going to happen. I don’t think I’d have been a terribly good prime minister. Or I would have been either very good or hopeless.’4

Williams is an interesting case. At her peak, polls suggested she was hugely popular with the wider electorate; she was committed and politically courageous, with a melodious voice. The sound of a leader’s voice matters. Williams’s was far more engaging than Margaret Thatcher’s. Castle’s diaries are punctuated with jealous references to how Williams was admired by both Wilson and the media. But in spite of her popularity, Williams was defeated at key moments, losing her seat in 1979, failing to hold Crosby for the SDP in 1983 having won a famous by-election there following her defection from Labour, and not winning a Cambridge seat in 1987. She never stood in a contest to be leader of either Labour or the SDP, although she became leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords, a relatively minor post. Williams never got into a position where she could be feasibly seen as the next prime minister; indeed, as she moved closer to such a place, voters rejected her. Williams failed to secure a safe seat for life, one of the fundamental qualifications for leadership. As a result, she suffered the weird experience of being hugely popular nationally – and with the likes of Harold Wilson – while living in justified fear of losing her seat.

There are three men who emphatically do qualify for the dubious honour of inclusion but do not feature in the book. Two Labour leaders, Hugh Gaitskell and John Smith, would almost certainly have become prime minister. Iain Macleod, Edward Heath’s chancellor after the 1970 election, might well have done. All three died prematurely. They are not included because, sadly, there is no mystery as to why they failed to reach the very top.

There is another category of politicians who do not qualify for inclusion in my list: those who might have been great prime ministers, even if they stood no realistic chance of reaching the very top. The case can be made for more or less anyone depending on your point of view. The former Conservative leader William Hague often gets quite a few votes when this game is played out on the radio or in articles. He does not make this book because there was not a single moment while he was Conservative leader after the 1997 election when he or anyone else thought he would win the subsequent election. When he was duly beaten in 2001 he resigned as leader, spending more time playing the piano, writing good books and earning decent money on the speech-making circuit. By the time he returned to the fray as shadow Foreign Secretary and then Foreign Secretary under David Cameron, all ambition had been sated. This does not mean he would not have made a good prime minister. It means he was never widely seen as a potential prime minister when he was politically active or had a realistic chance of reaching Number Ten.

On the other side, the same boundaries apply to the former Cabinet minister Alan Johnson, who was charming, decent, a natural communicator and experienced as a minister. He too might have thrived in the top job. But, as he has reflected, he did not win the party’s deputy leadership contest in 2007 and never fought a contest to be leader. Johnson struggled when Ed Miliband made him shadow chancellor.

In cases like Hague and Johnson, there are no mysteries to solve. They did not become prime minister because they had no chance – whatever their strengths of character. This is not a book based on my views or anyone else’s about who might have been a great prime minister. Such a book could be longer than War and Peace.

The failures of those included in this book require deeper explanation and exploration. All those who meet the criteria of ‘prime ministers we never had’ appeared to be in a position where the crown was within their reach. None of them seized the glittering prize, yet this book is not by any means a study of failure. The doomed figures were high achievers in varying ways. Some, like Jeremy Corbyn, were bewildered by how high they climbed. Most were disappointed they did not climb higher, but they had already achieved much in government or as leaders of the Opposition. The prime ministers we never had are very different from each other but are bound by one tantalizing common question: why did they fail to make the final leap? That is the question this book seeks to answer. Each chapter is not a full account of a political life. That would also make Tolstoy’s novels seem slim. Instead, the characters and their specific strengths and flaws are assessed, to discover why they got so seemingly close and yet in the end were so far from seizing the crown.

The demands on those who do reach the very top are immense. The coronavirus that began to rage across the UK in March 2020 presented even greater challenges in terms of leadership than the financial crash of 2008 did. There will be more pandemics, testing not only the health of a country but its economy too. The UK’s tottering social care provision was exposed tragically during the Covid-19 pandemic, but remedying the squalid fragilities of a lightly regulated sector will be expensive and complex. The NHS too is underfunded compared with health systems in equivalent countries. Meanwhile, climate change will only be addressed by leaders of vision ready to take tough decisions that might well be unpopular, at least in the short term. And now that the UK has left the EU, its place in the world is less clearly defined. The UK itself is vulnerable, as Scotland and Northern Ireland stir in different ways. Robust and resolute leadership is evidently required. But quite often the robustly resolute do not become prime minister, while those ill-suited to meet the titanic demands of leadership make it to Number Ten. Why is this?

The answers matter partly because if a prime minister has an overall majority, they wield considerable power. After his personal triumph in the December 2019 election, Boris Johnson was in a strong enough position to decide almost single-handedly his government’s response to the pandemic in the spring of 2020, as well as the form that Brexit would take – two historic sequences that would have been different under an alternative prime minister. There are endless similar examples of the near-presidential conduct of prime ministers, from Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist economic experiment to Tony Blair’s decision to back President Bush’s war in Iraq. These were partly personal crusades, and they would have taken a different form if others had made it to Number Ten.

I avoid too much counter-factual speculation. This is not a book about ‘Prime Minister Neil Kinnock’ or ‘Prime Minister Ken Clarke’. Obviously, the UK’s path would not have been precisely the same if any of the figures in this book had become prime minister. Whether the UK would be in a better place is inevitably another subjective judgement. We all have our own views, based on where we stand politically. However, I do make the case that if Heseltine had won the Conservative leadership contest in 1990, the course of history in the UK would have been dramatically different.

Similarly, if Kinnock, Ed Miliband or Corbyn had won general elections, the UK would be in a different place, as their victories would have meant a change of governing party. But how much space would any of them have had as prime minister? If Corbyn had won, he might not have secured an overall majority, and would have faced the constraining hell of the global pandemic as well as having to spend energy and time on addressing the still-unresolved Brexit question. Ed Miliband assumed he would be a prime minister in a hung parliament in 2015. Such a context would have limited his radical instincts, as would the dynamics in the Labour Party at a time when those who did not share his leftish views held senior positions. Nonetheless, if Miliband had won in 2015, there would have been no Brexit referendum. Miliband had bravely opposed the proposition in the election, and got little credit for his stance even from pro-EU newspapers. In the 2015 election, the pro-European Financial Times urged its readers to vote Conservative. In a near-incomprehensible editorial, the even more pro-European Independent argued for a return of the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition.

Kinnock, in 1992, also worked on the understanding that if he became prime minister it would be in a hung parliament. In such a context, he would have had to spend much energy on assembling support to win votes in the Commons, and would have had a tense relationship with his chosen chancellor, John Smith. As prime minister, John Major faced the nightmare of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) crisis in September 1992. Kinnock might have done too, although he has always maintained he and Smith would have adopted a different approach on gaining power. Gazing through the speculative fog, what is clearer is that Labour was more or less united in its approach to Europe. Major’s difficulties in legislating the Maastricht Treaty might have been avoided under Kinnock.

In truth, we will never know what would have happened if any of those in this book had become prime minister. Speculation is as fruitless as guessing what happens to characters in a novel without a clear ending. Subtle writers sometimes decide not to give a definitive resolution; our time as readers is better spent trying to make sense of what the author has decided to convey. Similarly, in the equally subtle and febrile world of politics, it is more fruitful to focus on what did happen to the prime ministers we never had, and to discover the reasons why they did not get to Number Ten.

With the exception of Rab Butler, I have known to varying degrees the prime ministers we never had that are featured in this book. As with the prime ministers in my previous book, I found them all more complex and interesting than the way they were often perceived or portrayed. I interviewed Roy Jenkins several times towards the end of his life, about politics and his biographies of Gladstone and Churchill. He was always generous with his wine at any time of day. On one occasion, the journalist John Lloyd and I went to interview him at his office in the Lords at 11 in the morning. Good wine was served. But Jenkins was also generous on a much more important level. He was widely mocked as a grand and lofty figure, but he had a refreshing and counter-intuitively modest curiosity, often asking about others in politics and the media. After interviews, he was always keen to talk about what was happening and how I as a columnist chose topics and individuals as themes. Jenkins once observed to me, accurately, how difficult it was for columnists in the era of New Labour and weak opposition, when the ‘only two dominant figures are Blair and Brown… in previous decades there were a greater range of big figures to write about on both sides.’ I was struck that, at the end of a mountainous career, Jenkins was still fascinated by the art of column writing.

Denis Healey was equally engaged and more mischievous when I interviewed him a few times, mainly about his period as chancellor in the 1970s. The interviews were decades after he was at the Treasury. He was passionate about the era in which he had played a part, and less curious, I sensed, than Jenkins about what was happening when Labour returned to power in 1997.

Barbara Castle was so mischievous she made me laugh out loud on the few occasions I interviewed her or met her. In the chapter on her, I quote extensively from one of my interviews, during which she revealed whether or not she had an affair with her friend Michael Foot. She was nearly blind at the time I knew her, and yet she could see sharply all that was happening in the early phase of the New Labour era. My exchanges with these three prime ministers we never had were all towards the end of their lives, all personal political ambition spent. They were free to reflect.

I got to know Neil Kinnock much better after he ceased to be Labour leader, and I continue to meet up with him regularly. The Observer columnist William Keegan and I have spent many long, convivial lunchtimes drinking too much wine and discussing politics with him. He can be as fun and insightful now as I remember him being when he was a rising star in the Labour Party. I recall observing him from a distance then: the youthful orator who could fill every hall in the land; the guest on TV chat shows; a star of the left who turned on Tony Benn at a pivotal moment. Then he became leader and endured nine years of hope and hell. I note that when he reflects on his time as leader, the pain is still there – as well as the ability to laugh as he highlights the farcical absurdities of leading Labour as the party went through a phase when it was almost impossible to lead.

All the prime ministers that never were challenge the caricatures that defined their public image. Perhaps Michael Heseltine does so most of all. At least that is what I found on the few occasions I interviewed him or spent a bit of time with him. He might have been a performer and intensely ambitious, but he also possessed a deep seriousness and sense of responsibility. When I asked him in a BBC radio studio about his party and Europe after he had left the Commons, he almost shook with anger and sorrow. I observed a similar surprising intensity in a different context. In the autumn of 1992 he was president of the Board of Trade in John Major’s government, and struggling with his decision to close several deep coal mines. Tory MPs were in revolt. Unusually, Tory-supporting newspapers backed the miners and not the Conservative government. My then BBC colleague John Pienaar and I had lunch with Heseltine at the height of the crisis. Heseltine deployed every implement on the table – knives, forks, salt and pepper pots, unused plates and glasses – to show what he was trying to do with the mines and to explain the support he was giving to those who would lose their jobs. I noticed that his hands were shaking as he moved the implements around. He had found the crisis traumatic and it had taken a toll on him, not because of the impact on his leadership ambitions but because of the burden of the responsibility. In terms of mastering policy implications he was not frivolous as Boris Johnson could be, or casually shallow as David Cameron often was. There was a weightiness to Heseltine. Yet it was the Etonian duo, Cameron and Johnson, who made it to Number Ten.

I interviewed Michael Portillo for a Radio 4 series on those who had lost their seats or elections at key moments in their careers. Famously, Portillo lost his seat in Labour’s 1997 landslide. He not only had to accept defeat but adapt also to the fact that voters were thrilled by his humiliation. ‘Were you up for Portillo?’ became the slogan of the night. He spoke openly about the saga and the degree to which it triggered a new outlook on politics and life. But he also admitted that, years later, he still looked at whoever was prime minister with a degree of envy.

To some extent, Portillo also had curiosity. When I was a guest on BBC One’s This Week, the political show in which Portillo formed an engaging double act with the Labour MP Diane Abbott, he was the most interested in the answers to questions and the least predictable in discussions. Curiously, there was the same enigmatic quality when he was at his peak as a potential prime minister as there was later, when he became more of a TV celebrity. He had changed as a public figure and yet the basis of his charisma had not. From seeking to be prime minister to becoming a TV presenter he was charming and engaged, yet also reserved, distant and self-contained.

I knew the Miliband brothers best of all, liked them both and found the leadership contest in which they were both candidates something of a nightmare, as did many other political journalists. During the New Labour era, I met up with them often – separately of course. I also saw a fair amount of Ed when he was leader and in the aftermath of his election defeat in 2015. The careers of the two Milibands took an unlikely course. Only Jeremy Corbyn can beat them in his even more bizarre political journey. They began as assiduously thoughtful special advisers, working behind the scenes in opposition and then in government – David committed to Tony Blair and Ed to Gordon Brown. Although they were written about often, they were not public figures for many years. They seemed fairly content with their background roles while others battled it out in public. Yet they became prominent politicians speedily once they had secured safe parliamentary seats. After which their careers developed with a weird intensity, partly fuelled by the fraternal rivalry but also by the way personal ambition took hold of them as if from nowhere. I did not get the impression they started out aching to lead their party or were even wholly sure at the beginning they wanted to become MPs. Yet both ended up ferociously determined to lead, more or less at around the same time.

The least likely course of any figure in this book was the one taken by Jeremy Corbyn. He makes the Milibands’ journey seem normal. Corbyn had no desire to be a leader even when he stood for the leadership contest in 2015. His rise and fall is one of the most remarkable stories in modern British politics. I used to interview him regularly, long before he became leader, when I presented GMTV live early on Sunday mornings. The production team discovered that Corbyn was willing to come to the studio, often at short notice, as he lived nearby. Over coffee afterwards he was always polite and modest. After he resigned as leader, some commentators suggested that Corbyn was a vain narcissist.5 I have never met a politician who was less vain. No doubt after he became leader the idolatry that greeted him at public events partly went to his head. It would go to the head of any human being. Before then, he was content to be a local MP and vote against his party leadership in the Commons on a regular basis. When he was leader I occasionally bumped into him jogging near Finsbury Park in north London. By then he had good cause to be wary of nearly all journalists, but he was always pleasant and unassuming in conversations.

During the period Corbyn was leader he never went in for personal attacks on anyone, even to the point that he struggled to launch an onslaught against Theresa May or Boris Johnson at Prime Minister’s Questions. Similarly, he was too decent to sack virtually anyone on his frontbench or in his office. These were failings in the context of leadership. A leader must be ruthless. And these were by no means his only flaws as a leader. Unsurprisingly, as an MP who had given no thought to leadership, he struggled to lead. I suspect that, far from being a narcissist, he was relieved on many levels not to have been prime minister. Even so, he got closer than many expected. In the aftermath of the 2017 election I had conversations with several Labour and Conservative MPs who told me, in the midst of the chaos of Theresa May’s premiership, that Corbyn could well be prime minister before very long. He never was.

Like those in my previous book, The Prime Ministers: Reflections on Leadership from Wilson to Johnson, the chapters that follow are based on a series of unscripted BBC talks, each one recorded in a single thirty-minute take. Some of the talks are still available on BBC iPlayer or YouTube. The themes, lessons and epic dramas are explored at much greater length in this book.

The prime ministers who never were form as much of a soundtrack to our lives as do the prime ministers. At their peak they were each talked about and analysed as much as the occupants of Number Ten were. Hope is a driving force in politics, explaining why so many keep going in spite of the overwhelming pressure. The characters in this book dared to hope that they would be prime minister. Their hopes were dashed, but each of them had good cause to dream.

1

RAB BUTLER

Rab Butler is the original prime minister we never had. Butler is one of those rare former Cabinet ministers whose name and deeds are still often cited. When they are, an observation usually follows, along the lines of, ‘Ah yes, Rab Butler, the best prime minister we never had’. Indeed, the persistent claim forms the subtitle of a recent biography of Butler, although the author wisely adds a question mark.1

The judicious question mark has its place not so much because of the adjective ‘best’. That is a subjective judgement. Rather, the justified doubt is over whether Butler was ever in a strong enough position to become prime minister, in spite of his remarkable career. On so many levels Butler was supremely well qualified. No one else in this book can compete with him in terms of experience and range. He held multiple roles for decades: a reforming minister, a modernizing party chairman and a stand-in prime minister. Butler had a high profile on the political stage from the 1930s until the Conservatives were defeated in the 1964 election. In each post he had a profound impact. Butler was not a ‘here today, gone tomorrow’ politician. He was a change-maker.

There is a striking contrast between Butler’s ministerial career at points when he might have become prime minister and the careers of some of those who did climb to the very top. Tony Blair and David Cameron had no ministerial experience when they became prime ministers. Margaret Thatcher was only briefly Education Secretary. John Major had held two of the most senior jobs, Foreign Secretary and chancellor, but only fleetingly.

Compare those examples of limited or no ministerial experience with Butler’s mind-boggling range. As a junior minister in the early 1930s he played a significant role in implementing plans that helped India become autonomous from the British Empire, a highly charged mission that included the handling of opponents within the Conservative Party – not easy for a senior minister, let alone a junior one. During the war he was responsible for education, passing the Education Act of 1944, one of the few examples of legislation that was still cited for its significance half a century later.

After the Conservatives were slaughtered in the 1945 election, Butler was a reformer in opposition, seeking ways of synthesizing Tory values with the fresh challenges and assumptions of the postwar era, one in which Labour ruled with a big majority. Blending a party’s traditional values with changing orthodoxies is an art form. Although not exuberant as a public performer, Butler was an artist in terms of encouraging his largely reluctant party to move with the times. As a result, the Conservatives soon resumed their traditional role of winning elections.

When he was made chancellor in October 1951, Butler faced the demands of strengthening a fragile post-war economy. There were oscillations in terms of progress and his own popularity, as there are for all chancellors who serve for more than a moment or two. But on the whole, the economy was stronger by the end of his spell at the Treasury than at the beginning. Butler moved on to become an innovative Home Secretary under Harold Macmillan in the late 1950s, as well as performing several other tasks. He was briefly Foreign Secretary in the run-up to the 1964 election. He even stood in when the actual prime minister was ill, on two highly sensitive occasions.

Most Cabinet ministers do not last for very long. They soon find they are not up to the job, fall out with their leader, or get bored too easily. Some are moved from department to department without staying long enough to leave any significant mark. Butler’s political CV is daunting and this is only a brief introductory summary. He had more experience than several incoming modern prime ministers put together.

Here is a depressing lesson of leadership: for aspiring leaders, there is greater safety in having no past of significance than one of such depth that controversies and consequences are recalled when the crown moves into sight. Butler’s patient, practical reforming zeal propelled him to the top of his party, but it was also a significant obstacle in the way of him becoming prime minister.

The proposals to give greater self-government to India were complex and highly contentious. Winston Churchill was one of many Conservative MPs who looked on warily at what the youthful Rab Butler was doing – an intimidating prospect. Party members were equally concerned as Butler in his role as junior minister put the case for what became the Government of India Act in 1935.

Butler was a genuine modernizer, unlike many more recent figures in the Conservative Party who have claimed this vaguely defined epithet for themselves. In the case of India he faced one last defiant cry from old-fashioned imperialists and took them on politely. Butler had a good relationship with local party members in his Saffron Walden constituency, but even they felt compelled to ‘express great apprehension lest the granting of self-government to India… may be injurious to the British Empire’.2 His first move as a minister was substantial but it alienated a significant section of his party. Genuine reformers are bound to antagonize those within their party who cling to the status quo.

In seeking change, Butler was not dogmatic. His determined pragmatism was on display from the beginning as he patiently sought ways of bringing doubters with him. He insisted regularly in the Commons that the proposals in relation to India were the product of compromise and determined expediency; they represented what Tony Blair would later call the ‘third way’. The British government retained a right to intervene if it judged governors in India were ruling irresponsibly. Self-government depended partly, and vaguely, on the consent of the Westminster government.

Inevitably, this third-way approach did not satisfy more ardent imperialists. Churchill and his supporters established the India Defence League, a pressure group committed to keeping India as part of the British Empire. In response, Butler was involved in setting up the Union of Britain and India, whose name articulated the ambiguity of the limited leap towards self-government. And so in his first ministerial role, Butler was at the heart of a divide within the Conservative Party, implementing seismic changes in a cautious manner. If there was a template for Butler’s career, this was it.

One of Butler’s great enduring strengths was fully formed from the beginning: his eagerness to work with non-Conservatives, including policy specialists and those from other political parties. He had consulted widely over self-government for India. In doing so he pushed at the boundaries of what a section of his party would accept, and yet he sought to manage internal dissent as subtly as possible, which was another of his talents. Churchill praised Butler even as he vilified more senior ministers, quite an achievement for the youthful politician. Butler had been careful to treat Churchill with solicitous respect in the Commons and in private meetings. He was alert to the political mood at any given time and knew Churchill was a potential leader. More immediately, Butler recognized that the great ego would erupt less ferociously if treated with charming deference.

There were other strengths. From the beginning of his career Butler was a doer who derived satisfaction from implementing policies as much as from the theatre of politics. Some colleagues thought him closer in certain respects to a civil servant, mastering detail and looking towards putting policies into effect. This was a misjudgement, mistaking his capacity for work and his self-effacement as the traits of a technocrat. Butler was ideologically rooted on the centre right, a politically deft one-nation Conservative capable of finding the means to bring about ends, forging new alliances and creating a consensus around thorny issues. He did not have the temperament of a civil servant. He was a constructive and creative Conservative politician.

When Butler was made president of the Board of Education in 1941 the same patterns recurred. There was already a broad but fragile political consensus about the need for sweeping changes to education provision. As is often the case with an apparent consensus, when specific measures were proposed there was little agreement within parties, let alone between them.

The need for reform of schools had been widely recognized since the end of the First World War. In 1918, still exerting a restless radical verve, Liberal prime minister David Lloyd George had passed an Act aimed at raising the school leaving age and giving more responsibility to local authorities to run schools in place of overstretched churches and other religious institutions. The changes were never implemented, largely due to resistance from parts of the Conservative Party. Butler’s triumph as Conservative Education Secretary was to realize the essence of Lloyd George’s vision.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, Butler was getting used to making moves that challenged orthodoxies in his party. For some Conservatives, education was still seen as a religious responsibility even though their perception was at odds with reality. Churches did not have the resources or the inclination to meet the demand for school places. As with his plans for India, Butler had to deal with the wariness of Churchill, who was now a wartime prime minister rather than a formidable backbencher. Churchill wanted Butler to focus on schools delivering as best they could in wartime conditions. Butler insisted that the education system needed to adapt more fundamentally to modern conditions. He was much less demonstrative than Churchill but far more ambitious, at least in terms of domestic reform.

Again, Butler looked beyond the boundaries of the Conservative Party, calculating rightly that in the national wartime government he would have the support of Labour ministers – including the deputy prime minister and Labour leader, Clement Attlee. In making the case for more secular education and a school leaving age of fifteen, rising to sixteen, Butler cited the left-wing political philosopher R. H. Tawney as much as he did more conservative advocates of change.

As with his approach to India he was not recklessly inexpedient. He sought again a third way, although in doing so from the right Butler was more at ease with embracing some on the left than Blair tended to be when he navigated this deceptively tricky terrain as Labour prime minister. Blair was not known for citing Tawney very often, while Butler was freer to do so as he wooed Labour figures.

Butler was a navigator of what was possible, and more of an incrementalist than his internal opponents dared to realize or acknowledge. Following complex negotiations with religious leaders, a majority of the Anglican church schools were effectively absorbed into the state system. As part of the compromise, a third of them received higher state subsidies while retaining autonomy over admissions, curricula and teacher appointments. Churches had lost some of their grip but by no means all. Well into the twenty-first century, some church schools would still be targeted by middle-class parents who discovered an attachment to Christianity in order to secure a place for their children. Butler’s historic education policies had distinct limits and yet marked a radical break with the past.

The most enduring reform of the 1944 Act established secondary education at the age of eleven, while abolishing fees for state secondary schools. The Act also renamed the Board of Education as the Ministry of Education, giving it greater powers and a bigger budget. Subtly, the legislation was both a move towards greater centralization and an assertion of localism, with councils acquiring more responsibility for local schools. The Act hinted at a much bigger vision of how to manage a public service through robust central and local government. The hint was not followed through, however. Following decades of confused corporatism in the 1960s and 1970s, the UK government opted for weaker central government and moribund local government after 1979, a combination that led to a more atomized state. By then, Butler’s one-nation conservatism was out of fashion.

Even so, the 1944 Act became totemic. On its sixtieth anniversary, the chief inspector of schools, David Bell, noted in a lecture:

It is no wonder that the 1944 act is often referred to as the Butler act, as a measure of the respect for Rab Butler’s contribution to the development of state education. The fact that we continue to work towards his educational goals reflects the high quality of his forward thinking and the debt we owe him for stimulating and guiding great steps forward in educational provision in this country. It is time now for the generations who have benefited from Butler’s visionary thinking to repay that debt, and seek to improve further the life chances of the generations to come.3

Not many Cabinet ministers have their name associated with reforms that are the subject of a lecture decades later. Most are not associated with reforms while they are ministers. Yet Butler was a cautious visionary. His changes meant that, although pupils had at last the benefits of a later school leaving age, they faced the prospect of selection at eleven, an arbitrary age for a child’s long-term fate to be determined. Some church schools continued to flourish and became part of a new elite.

In spite of the reactionary strands of the legislation, the Act marked a big leap on both practical and ideological grounds, guaranteeing British children an education until they were at least fifteen. In some respects, Butler was framing arguments about a more benevolent state that came to underpin the 1945 Labour government. This does not mean Butler was by any means a figure of the left, but he was willing to contemplate a bigger role for government, not least in the context of the 1940s and the Second World War. He was ahead of his party on this – the only place for a genuinely reforming minister to be, but not one that necessarily endears a potential leader to local members. Butler was as personally ambitious as any of his Conservative Party contemporaries, but he was a tireless reformer who did not always calculate how this left him in terms of becoming leader.

After Labour’s victory in 1945, Butler became a thoughtful opponent. Quite a lot of the Conservative frontbench was surprised to be out of power after the war. Butler kept going, applying the same intelligent energy as he had done in government. Here too there are parallels with the approach of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown in the build-up to the 1997 election. They were obsessed with the question of why Labour kept losing elections, and they sought, with varying degrees of success, to synthesize the values of their party with the attitudes of the voters who’d abandoned them – or who’d never supported them to begin with. Both became prime minister. Butler performed at least as effective an act of synthesis for the Conservatives, but he did not become prime minister.

After Attlee’s victory in 1945, Churchill’s instinct was to attack Labour with a renewed ferocity without looking too closely at his own party. He was a restlessly impatient loser. Butler was less complacently bombastic, recognizing there was little to be gained from mounting an onslaught that by implication challenged the judgement of the voters. Attlee had won a landslide. Butler knew the Tory message had to be much more sophisticated than ‘the voters got it wrong’.