Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

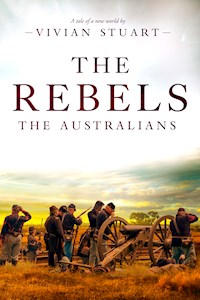

- Serie: The Australians

- Sprache: Englisch

The sixth book in the dramatic and intriguing story about the colonisation of Australia: a country built on blood, passion, and dreams. Twenty thousand kilometres and four months of sailing are what stands between England and the colony of Australia. In his struggles to bring order in the colony, and to protect its settlers from abuse of power, and injustice, Governor Bligh is up against some powerful enemies and mischievous schemers. Three strong-minded governors have failed to complete the task before him ... And England seems to have had enough of the war against France. Rebels and outcasts, they fled halfway across the earth to settle the harsh Australian wastelands. Decades later — ennobled by love and strengthened by tragedy — they had transformed a wilderness into a fertile land. And themselves into The Australians.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 443

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Rebels

The Australians 6 – The Rebels

© Vivian Stuart, 1981

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2021

Series: The Australians

Title: The Rebels

Title number: 6

ISBN: 978-9979-64-231-2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

The Australians

The ExilesThe PrisonersThe SettlersThe NewcomersThe TraitorsThe RebelsThe ExplorersThe TravellersThe AdventurersThe WarriorsThe ColonistsThe PioneersThe Gold SeekersThe OpportunistsThe PatriotsThe PartisansThe Empire BuildersThe CraftersThe SeafarersThe MarinersThe NationalistsThe LoyalistsThe ImperialistsThe Expansionists1

Justin tacked his cutter expertly into Sydney Cove, and as her mainsail came down, Andrew, stationed in her bows for that purpose, let go her anchor and she came to within hailing distance of Robert Campbell’s wharf.

The anchorage looked peaceful enough, with its usual complement of trading vessels, whalers, and river craft swinging to their moorings in the light offshore breeze. The colonial frigate, H.M.S. Porpoise, was absent, however, and remarking this as he came aft to assist Justin to stow canvas, Andrew said with relief, ‘The situation must have improved if the governor has let her go, don’t you think?’

Justin, concentrating with the single-minded detachment he always gave to the securing of his small command, grunted indifferently and appeared not to have heard, but a little later, their chores completed, he dispelled his stepfather’s brief illusion.

‘She was due to go to the Cape for stores just after we sailed. I don’t reckon the governor had much choice.’ He jerked his wind-ruffled fair head in the direction of the wharf. ‘But if you want to find out what’s afoot, we could make our report to Mr Campbell right away, before he comes to us. I see the Parramatta’s here.’

‘The Parramatta?’

‘Aye—Mr Macarthur’s schooner.’ Justin grinned. ‘With two constables in uniform patrolling her deck and her hatches battened down.’

The boy’s sharp eyes had missed nothing, Andrew thought, but he asked, puzzled, ‘What does that signify, lad?’

‘Trouble,’ Justin replied, still grinning. ‘She’s under arrest. There was some story about her master having smuggled an escapee on board and given him passage to Otaheite. The provost marshal had her searched twice before she was allowed to sail from here. They found no one, but I suppose they’ve managed to pin it on her people now.’ He shrugged. ‘I’ll get the dinghy.’

Robert Campbell gravely confirmed this supposition when they joined him in his dockside office twenty minutes later.

‘Sydney Town is agog, waiting for the storm to break, as I fear it’s about to, and the wildest rumours are gaining credence—each wilder than the last. The most recent I have heard is that Mr Atkins, as judge advocate, has issued a warrant for Mr Macarthur’s arrest, to be served on him today by Francis Oakes in Parramatta.’ The port naval officer spread his big, strong hands in a gesture of resignation. ‘Naturally, by reason of my office, I’m embroiled in the unhappy affair. I had to place the Parramatta under arrest, for a start. The civil court ordered her owners to forfeit their bond, and they both refused to do so—although the master made a full confession of guilt.’ He told of the crew’s decision to come ashore in defiance of port regulations and added wryly, ‘Now the judge advocate has convened the magistrates bench for tomorrow morning, and I am required to sit ... presumably to hear the case against Macarthur. If, that is to say, he submits to Oakes’s warrant and appears before us to answer the charges.’

‘Don’t you think he will, sir?’ Andrew asked, hearing the doubt in his tone. ‘Surely he cannot refuse to appear?’

‘The good Lord in heaven alone knows what he’ll do, Captain Hawley!’ Robert Campbell returned. ‘He is as devious and unpredictable as they come. And who knows better than John Macarthur how to bend the law to his advantage? He’s been doing it for years—harassing honest fellows like Will Gore and Lieutenant Marshall, and that poor devil Andrew Thompson with his scurvy, trumped up lawsuits! This colony has suffered enough from him, and the governor has to make a stand against Macarthur and the corps, who will, it goes without saying, support him whatever he elects to do. If we could rid New South Wales of the lot of them, it would be our salvation, in my view. My only fear—and it’s one that haunts me—is what will be the consequence should we try and fail.’

He spoke with deep feeling and Andrew, who had always respected his integrity and enterprise, nodded in sober agreement. ‘You can count on my support, Mr Campbell, for what it is worth,’ he offered.

‘Good—that’s what I’d hoped. But it is a pity you are not a civil magistrate. You were never appointed to the bench, were you?’

‘No, I was not. The governor—’

‘The reasons scarcely matter now, do they?’ Campbell put in. ‘But you would be eligible to serve on a military court, should it come to that, I presume?’

‘I, too, presume so, sir. Unless His Excellency were to raise objections.’

Robert Campbell smiled thinly. ‘Because of your marriage to this young man’s mother, you mean?’ His smile widened into warmth as he glanced across at Justin. ‘He’s a very fine young man, if I may say so, and a credit to both his parents. I have a proposition to put to you, Justin, when we conclude this discussion ... so bear with us, will you?’ He turned again to Andrew. ‘Did you bring your wife back with you from Van Diemen’s Land, Captain Hawley?’

Andrew faced him squarely, his expression carefully blank. ‘No, sir. I did not receive official permission for her to accompany me.’

‘But you are returning to the governor’s service?’

‘I am, Mr Campbell. In obedience to His Excellency’s command.’

Robert Campbell studied him for a moment or two in silence; finally, as if reaching a decision, he held out his hand. ‘Well, as far as I am concerned, you are very welcome. When you have reported your return to Governor Bligh, I should be more than pleased if you would dine with my family and myself. There may be fresh developments by this evening which would bear further discussion.’

Andrew thanked him and rose to take his leave, but the big man waved him to wait.

‘There is the proposition I want to put to Justin,’ he said, again smiling at the boy. ‘Tell me, have you a charter in prospect for the Flinders, or is she for hire?’

‘I’ve nothing in mind, sir,’ Justin assured him, ‘save a visit, on my mother’s account, to her farm at Long Wrekin.’

‘That is on the Hawkesbury, is it not—the holding beyond Dawson’s property?’ Receiving Justin’s nod of confirmation, Campbell went on, evidently pleased, ‘Ah, then it will fit in admirably. I had accepted a hiring from that somewhat formidable parson, the Reverend Caleb Boskenna, to convey himself, the two young ladies who are his wards, and his assigned labourers to his newly claimed property on the Hawkesbury. I’ve a map somewhere ... yes, here it is.’ He spread the map out on his desk and, with a blunt forefinger, indicated the site of the new holding.

Justin studied it, his eyes, Andrew noticed, suddenly bright with interest.

‘The vessel I had chartered to Mr Boskenna —the Phoebe—ran aground three days ago and stove her bottom in off Manly beach,’ Robert Campbell explained. ‘Her damned skipper, I suspect, was drunk though he won’t admit it! But I haven’t anything else of a suitable size to replace her, and Boskenna is giving me no peace. It would be of great assistance, Justin, if you would hire me the Flinders and take the holy man to his destination. You could call at your mother’s farm on your way back. Boskenna’s in a hurry. And I’d pay you a fair price for the hiring.’

Justin’s instant acceptance of the offer left Andrew faintly surprised, but he offered no comment, and the boy said eagerly, ‘I can have the Flinders ready to sail tomorrow morning, Mr Campbell. She’ll need swabbing down before the two young ladies come on board, and I’ll require stores and water ... and some blankets, too. And a good man to crew for me if you can spare anyone.’

‘I can let you have Cookie Barnes.’

‘He’ll suit me fine, sir. And if I give you a list of provisions, can I have them before dark?’

You can have them in an hour—and Barnes as well, if you want him. I’ll send word to the reverend gentleman that his waiting is over. Now about the hiring charge ...’

Andrew made his excuses and left the two of them to settle details of the hiring. One of Robert Campbell’s oared boats took him across the cove to the government wharf. Pausing only to change into uniform at the house of William Gore, the provost marshal—who repeated the news Robert Campbell had already given him—he left his kit bag in the care of Gore’s pretty young wife and went, with some foreboding, to report his return to the governor.

Bligh’s reception was unexpectedly warm and affable. He said, after inviting Andrew to be seated, ‘You’ll have heard what’s going on, no doubt? You’ve come from Robert Campbell?’

‘Yes, sir, I have, and I—’

The governor raised a hand to silence him. ‘I intend to deal with John Macarthur, once and for all, Hawley. But before I say any more, I should tell you that I have despatched a full pardon to Hobart for your wife. She may return here by the first available vessel to touch there.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ Andrew managed. ‘Thank you.’

Francis Oakes was in his bakery when the judge advocate’s messenger dismounted from his lathered horse and thrust the warrant he had been ordered to deliver into his flour-caked hand.

The stout, perspiring Oakes read it with undisguised dismay, swearing under his breath.

‘God in heaven!’ he exclaimed, turning on the trooper, the warrant held at arm’s length as if he feared that it would burn his fingers. ‘I can’t serve this—I can’t arrest Captain Macarthur! Here, take it back—serve the blasted thing yourself, plague take you! I’ll have nowt to do with it. It’s as much as my life’s worth to cross that gentleman an’ Mr Atkins knows it.’

The trooper, who had ridden hard in the heat, visualising the mighty draught of ale he would be entitled to demand at the end of his sixteen-mile journey, backed away in alarm.

‘’Tis addressed to you, Mr Oakes, as chief constable o’ bloody Parramatta. I’ve carried out my orders—I’ve delivered it to you an’ I ain’t doin’ no more, understand?’ He clambered back into his saddle and, spurs dug deep into his mount’s heaving sides, made off down the street at a shambling trot toward the Freemason’s Arms.

Oakes stared after him, cursing helplessly. It was two-thirty in the afternoon; the time when, as a rule—the last batch of freshly baked bread would be taken from the ovens—he sought his bed for a well-earned rest before his evening inspection of the Factory and the muster of his constables.

Not for the first time he found himself regretting the burden his various duties imposed on him. True, he was paid for his two official posts, as chief constable and factory superintendent, and both enhanced his standing in the community; but the bakery was becoming increasingly profitable, with convict labour and girls from the Factory assigned to the work and demand for his wares growing almost daily. He could afford to resign from the constabulary, and indeed, he would probably be compelled to do so if he dared to enter Elizabeth Farm with the document he had just been given. He read the warrant again, sweat breaking out all over his body and running in rivulets down his unshaven cheeks.

It was one thing to serve the plaguey warrant, but as for arresting John Macarthur and taking him to Sydney to face the magistrates’ court ... good Lord alive, Macarthur would probably shoot him in his tracks before they had covered half a mile! Francis Oakes drew in his breath sharply and glanced behind him to where the bakery workers were already starting to dampen down the fires.

Usually he made a point of inspecting and counting the loaves they had produced—being convicts, they were light-fingered and prone to steal if he relaxed his vigilance. Today, however, he simply peered at the laden shelves without any attempt to check their contents and stumbled off to his own house, leaving the foreman to close up and dismiss his workers. The loaves of bread would be distributed in the morning.

Oakes’s house—a substantial, brick-built bungalow in keeping with his position—was deserted, and Oakes recalled then that his wife and daughters had gone on a shopping expedition to Sydney. It was just as well, he thought glumly as, having refreshed himself with a long draught of beer, he lay down, fully clothed, on his bed. Clacking female tongues would be of no help to him when he sought to come to terms with his present problem.

He lay back, his head resting on his two linked hands, and tried to give the problem his full attention, but he was tired. He had started work at the bakery before dawn, and within a few minutes of lying down, he fell into a heavy, dreamless sleep, his snores the only sound in the silent, empty house.

It was dark when he wakened and staggered dazedly to his feet. Memory returned and with it all his earlier doubts and fears. Plague take it, he thought wretchedly, struggling to light one of the whale-oil lamps, it must be almost five hours since the trooper from Sydney had thrust that damnable warrant into his reluctant hands and ridden off, caring little for the trouble he had caused.

The warrant would have to be served. That was his duty, and it was not one that he could foist upon one of his constables—he had to serve it himself, God help him! As the trooper had pointed out, it was addressed to him and bore the judge advocate’s seal. He would invite official retribution were he to ignore it, and perhaps, if he were to explain the circumstances to John Macarthur and apologise for being the unwilling bearer of such an unwelcome summons, it would not be held against him.

Oakes picked up the lamp and went outside. He drew water from the garden well, washed and shaved, and then dressed in his official uniform. There was no time for a meal; he would have to make do with a loaf of his own bread and the hunk of goat cheese which, it seemed, was all that his wife had left in the larder for his sustenance. He washed down his modest repast with several beakers of Cape brandy and then called at the police post for his horse. A considerably heartened Constable Oakes rode down Parramatta’s dimly lit main street to pay his customary evening visit to the Factory.

This evening, as always, the women were bickering. There was a discrepancy in the weaving shed that smacked of pilfering; two of the inmates had to be consigned to the stocks for fighting and there was a birth to record. Francis Oakes lingered over these routine tasks for as long as he reasonably could, refreshing himself with tots of rum in an effort to keep up his spirits, and taking his time over the handwritten entry in the birth register, which normally he left for the convict clerk to complete.

Finally, conscious that he could delay no longer, he remounted his horse and, with a sick sensation in the pit of his stomach, set off on the short ride to the Macarthurs’ imposing residence at Elizabeth Farm.

John Macarthur was enjoying a pipe of homegrown tobacco with his eldest son, Edward, before retiring for the night. Their talk was of wool prices on the steadily expanding home market and of increased yields from their fine Merino flock at Camden. The resulting profits were high enough to allow the purchase of Edward’s commission in a good British regiment, and the boy, elated by his father’s promise to set the money aside for this purpose, started eagerly to express his gratitude.

‘Father, in truth I—’ He was interrupted by an urgent pounding on the front door.

‘What the devil!’ his father exclaimed. ‘Who can it be at this ungodly hour? Damme’—he gestured to the clock above the fireplace—‘it’s gone eleven of the clock! Go and see who it is, Ned. If it is no one of consequence, bid him return in the morning. I don’t know about you, but I’m done up ... it’s been a deuced long day.’

Edward obediently tapped out his pipe and went to the door. There was a brief altercation, Macarthur heard his son’s voice raised in protest, and then he came back into the candle-lit parlour, red of face and clearly upset, with Francis Oakes at his heels.

‘It’s Mr Oakes, sir,’ he explained, ‘and I had to let him in, he ... he says he has a—a warrant for your arrest!’

‘What’s that?’ John Macarthur was on his feet, his voice ominously low and controlled. ‘Come in, Oakes, for the Lord’s sake! Is what my son says true? Have you a warrant for my arrest?’

‘I regret to say I have, sir,’ Oakes admitted. ‘But ’tis no doing of mine, I give you my word, sir. I’d rather have cut off my right hand than serve it on you, but I ain’t been given no choice, you understand. As head constable, I’m bound to obey the orders I’m given, and—’

‘Yes, yes, I understand,’ John Macarthur interrupted harshly. ‘But what charges are brought against me? Tell me that, if you please.’

‘The charges are set out in the warrant, sir,’ Oakes stammered unhappily. ‘An’ signed by Mr Atkins, sir, as judge advocate. But I—’

‘Let me read the infernal warrant, man,’ Macarthur demanded. ‘here, give it to me ... Ned, a candle, boy, on the table beside me. I want to see what devilry that drunken swine Atkins is up to now!’

Both Oakes and his son obeyed him instantly.

The warrant spread out on the table in front of him, Macarthur read its contents with mounting indignation.

Whereas complaint hath been made before me upon oath, that John Macarthur Esq., the owner of the schooner Parramatta, now lying in this port, hath illegally stopped the provisions of the master, mates and crew of the said schooner, whereby the said master, mates and crew have violated the colonial regulations by coming unauthorised on shore, and whereas I did by my official letter, bearing the date the 14th day of this instant December, require the said John Macarthur to appear before me on the 15th day of this instant December, at 10 o’clock of the forenoon of the same day, and whereas the said John Macarthur hath not appeared at the time aforesaid or since:

These are, therefore, in His Majesty’s name, to command you to bring the said John Macarthur before me and other of His Majesty’s justices on Wednesday next, the 16th instant December, at 10 o’clock of the same day, to answer in the premises, and thereof fail not.

Given under my hand and seal at Sydney, this 15th day of December 1807.

The signature was Atkins’s and the communication was addressed to Mr Francis Oakes, Chief Constable of Parramatta.

John Macarthur swore softly and pushed the warrant across the table to his son. ‘You know, Oakes,’ he said, without raising his voice, ‘had the person who issued that pernicious document served it upon me himself—instead of charging you with the task—I would have spurned him from my presence, by God I would! As it stands, I shall treat it with the contempt it and its author deserve. In a word, Oakes, I shall ignore your damned warrant. Is that quite clear?’

‘It’s clear enough, Captain Macarthur sir,’ Oakes agreed ruefully. ‘An’ if it was left to me, sir, I’d do no more. But, sir, it ain’t left to me, is it?’

‘What the devil are you getting at?’

‘Why, sir,’ the chief constable muttered, avoiding Macarthur’s cold gaze, ‘I’m ordered to bring you to Sydney to make your appearance afore the magistrates’ bench tomorrow morning, sir.’

‘In felon’s chains, Mr Oakes?’ John Macarthur challenged. ‘You’re alone, are you not—and unarmed?’

‘I thought it best to come alone, sir. I was hoping—well, that you’d appreciate my position and come with me of your own free will, like. Seeing as that warrant is official, sir.’

‘And if I refuse?’ Macarthur’s eyes were blazing, and Oakes backed away from him in alarm.

‘They’d order me to seize you, sir,’ he answered, wretchedly conscious of his own powerlessness.

‘And lodge me in your loathsome jail, I suppose,’ Macarthur flung at him. ‘Imagine that, Ned,’ he added, turning to his white-faced son. ‘Not only is that evil man Atkins determined to bring about my ruin—he and Bounty Bligh intend to treat me as a criminal! Well, Oakes, you can ride to Sydney and inform Mister Atkins and his bastard Excellency that I have committed no crime, and that—since my conscience is utterly clear—I decline to answer their summons.’

‘But, sir —’ Oakes pleaded, his voice choked, ‘I’ll be sent back. I’ll—’

‘Damn your eyes, fellow!’ Macarthur was really angry now, his chilly control slipping. ‘If you come back, then you’d best come well armed, for I can tell you this—I’ll never submit till blood is shed! Before God, I’ve been robbed of a ship worth ten thousand pounds by these—these unmitigated scoundrels, and now they seek to hound me into their courts on spurious charges!’ He flung the warrant in Oakes’s direction, grabbing it wrathfully from young Edward’s nervous hands. ‘Take this infamous paper and return it to those who sent you here!’

‘Father,’ Edward began, ‘I beg you to consider the consequences. Surely, sir, you—’

John Macarthur cut him short. ‘It’s all right, Ned, don’t worry,’ he said, with a swift change of tone. ‘If we let them alone, they’ll soon make a rope to hang themselves.’

‘Sir,’ Oakes begged, in desperation. ‘If I’m to take this warrant back to Mr Atkins, will you at least give me a letter, signed by yourself, sir, to make it clear that I’m doing so at your behest? If you don’t, Captain Macarthur—if I go in without you, sir, they’ll have me charged with dereliction o’ duty, and—’

‘Oh, very well,’ Macarthur agreed, with less irritation than he had hitherto displayed. ‘Ned—a pen, dear lad, and paper, if you please. I’ll give this poor fellow his letter.’

Edward, galvanised into action, fetched him a quill and an inkwell from his mother’s bureau and, hunting in one of its drawers, found some sheets of writing paper. He set them down on the table and his father started to write, the quill scratching across the paper in his haste. The letter consisted of six lines, and Macarthur said, not looking up, ‘I’ll read this to you, Oakes. It’s addressed to you and runs:

You will inform the persons who sent you here with the warrant you have now shown me and of which I have made a copy that I will never submit to the horrid tyranny that is attempted until I am forced, and I consider it with scorn and contempt, as I do the persons who have directed it to be executed.

There, my good man ... ’ He signed it with a flourish. Then he rose and waved Edward to take his place at the table. ‘The warrant, if you please.’

‘The warrant, sir?’ Oakes echoed blankly.

‘Yes—give it to my son. Now, Ned, be so good as to make a copy of this iniquitous document and of my reply. In a fair hand, boy ... we may yet need copies to exhibit in court.’

Edward, a worried frown creasing his smooth young brow, did as he had been bidden and, meanwhile, John Macarthur reached for a handsome cut glass decanter standing on the sideboard. Pouring two glasses of brandy, he passed one to Oakes.

‘I imagine this will be as welcome to you as it is to me, Mr Oakes.’

Francis Oakes thanked him obsequiously, relief at this ending to the unhappy affair evident in his voice and eyes as he raised his glass. ‘Your very good health, Captain Macarthur, sir!’

John Macarthur sipped his brandy in silence. When Edward had completed his copying, Macarthur took the warrant and his own note and offered them gravely to the head constable. ‘God speed you on your way, Mr Oakes. But remember, will you not, that you will require to be armed if you come a second time seeking to tear me from the bosom of my family in order to confine me in your jail?’

‘I trust it won’t come to that, sir,’ Oakes assured him fervently. He set his empty glass down, bowed awkwardly, and made for the door.

When the sound of the muffled hoofbeats of Oakes’s mount had faded into the distance, Elizabeth Macarthur came from her bedroom, white of face and wrapped in a hastily donned robe.

‘I heard voices,’ she said, looking up anxiously into her husband’s face. ‘John, my dearest, was it not Mr Oakes who called on you? For mercy’s sake, what did he want of you?’

Her husband told her in a few brief and bitter words, pacing the narrow confines of the shadowed room, his voice harsh with remembered anger as, in the re-telling, the full enormity of what had occurred was borne on them all.

‘Bligh and that miserable drunken sot Atkins are determined on my ruin, Elizabeth,’ he said. ‘They have flung down the challenge, and I must accept it—I must fight them!’

‘Did you not know that they would, John?’ Elizabeth reproached him. ‘By taking the action you did over the Parramatta, did you not know what the result would be?’

John Macarthur caught his breath. There was a bright gleam in his eyes as he halted opposite her and took both her hands in his.

‘Yes,’ he conceded. ‘I think, in my heart, I did. You heard my conversation with George Johnston, of course, the other night. And you approved, did you not?’

‘Let us say that I did not voice my disapproval,’ his wife amended. ‘For of what use would it have been to do so when you have made your mind up as to what course you intend to pursue?’

‘But I shall have your support, my dear?’

‘I am your wife, John. I will always support you.’

‘Right or wrong?’ Macarthur suggested wryly.

‘I did not say that,’ Elizabeth countered. She glanced at their son, smiling although her eyes were suddenly filled with tears. ‘Ned dear, what is your view?’

‘I’m worried about the letter father gave Mr Oakes,’ Edward confessed. ‘See for yourself, Mamma. It is dangerous—it is defying the authority of the magistrates, as well as that of Atkins, which would not matter so much. And I think it’s implying an insult to Captain Bligh.’

He gave her the copy, and Elizabeth Macarthur read it with furrowed brows. She said, with dismay, as she returned it to him, ‘I agree with Ned ... it is dangerous. They could use it against you, John.’

Macarthur read the letter again and shrugged.

‘I was angry when I wrote it, but damme, you’re both right! They could use it against me. Ned ... ’ he turned to his son, but Edward forestalled him.

‘I’ll ride after Oakes and get it back, sir,’ he offered. ‘He’s only been gone ten minutes. I’ll have no trouble catching up with him.’

He was off before either of his parents could reply, shouting for one of the drowsy servants to rouse himself and saddle a horse.

‘You must keep a tight rein on your temper, my love,’ Elizabeth Macarthur advised gently when they were alone. ‘Bligh is notorious for his outbursts, as you well know, and you may well defeat him by provoking such an outburst. But not unless you consider every move you make and act calmly. Let him go too far.’

‘The swine already has,’ her husband retorted, but his anger had faded, and he eyed Elizabeth with deep affection as she refilled his glass and waved him back to his chair, seating herself on its arm beside him. ‘Ned will retrieve that infernal note of mine, and then all will be well.’

But Edward returned, almost an hour later, and one glance at his face sufficed to tell both of them that he had failed in his mission.

‘Oakes wouldn’t give the letter back, Father,’ he said. ‘The wretched fellow insisted that he must keep it, in order to explain to the damned judge advocate why he had failed to bring you with him to Sydney. I offered him money—all I had on me—but he wouldn’t listen. So I’m afraid—’

‘But I am not,’ Macarthur assured him. He rose, elaborately stifling a yawn. ‘It cannot be helped, Ned, and it’s my fault, not yours. Let us get some sleep, shall we? Tomorrow I shall go to Sydney and show myself openly round town. Let them try to prove their ludicrous charges, and I will cry ‘Tyranny!’ And’—he smiled from his son to his wife—‘by heaven, I will sue Robert Campbell for depriving me of possession of the Parramatta! I’ll swear a writ against him for ten thousand pounds!’

‘Mr Campbell is on the bench, John,’ Elizabeth reminded him.

He laughed and took her arm. ‘So much the better, my love. Johnston and Abbott are also rostered this week. I shall not lack friends. Come—let us retire to bed. Tomorrow will be a busy day, I think.’

Francis Oakes delivered the letter and an agitated account of his attempt to serve the warrant on Captain John Macarthur the following morning. He found Judge Advocate Atkins at breakfast, in the company of Lawyer Crossley, and observed without surprise that, despite the early hour at which he had presented himself, Atkins was far from sober.

Crossley, however, had all his wits about him, and after a brief, whispered conversation with his legal superior, he thrust letter and warrant back into Oakes’s hand and said crisply, ‘Take these to His Excellency the Governor at once. When he’s read them—unless he gives you any instructions to the contrary—return and make a sworn deposition before the bench as to your endeavour to serve Mr Macarthur with the warrant. Is that clear? D’you understand what you’re to do?’

‘Aye,’ Oakes conceded reluctantly. ‘It’s clear enough, but I done my duty, Mr Crossley, to the best o’ my ability. T’ain’t right to put no blame on me. An’ if His Excellency’s led to believe as I’m at fault, sir, I don’t reckon as I’ve deserved it.’

‘Tut-tut, man, no one’s blaming you!’ Crossley retorted impatiently. ‘Just do as I tell you. The bench will be sitting at ten o’clock, and if Mr Macarthur fails to present himself before them, then you’ll be required to tell them why.’

‘Suppose he don’t fail to present himself?’ Oakes argued. ‘What then?’

Atkins belched loudly and waved him to silence. ‘Don’t be a damned fool, Oakes!’ he growled. ‘He’s no intention of answering the charges. Off with you to Government House and hurry—we’ve no time to waste.’ He belched again and reached for the bottle in front of him, a gleam of triumph in his bloodshot eyes. To Crossley he added thickly, ‘We’ve got him by the short hairs this time, George, by God we have!’

Francis Oakes waited to hear no more. At Government House, he was received by the secretary who, to his unbounded relief, took his documents from him and left him to wait, sweating profusely, in the anteroom. The governor did not require to see him. Griffin returned a few minutes later to echo Lawyer Crossley’s instructions to him to make his deposition to the magistrates when they assembled at ten o’clock.

‘His Excellency desires Mr Atkins to wait on him forthwith,’ the young secretary said, his tone a trifle uncertain. ‘Is he ... ah ... that is, Mr Oakes, perhaps you would be so good as to inform him?’

‘I will,’ the chief constable answered sourly, ‘but I reckon he’ll need Mr Crossley along to keep him on his feet!’

Edmund Griffin nodded in wry understanding.

‘Then if you would please inform both gentlemen, and’—he returned the warrant and John Macarthur’s letter—‘take good care of these, Mr Oakes. I think they will prove of great importance.’

The magistrates, when they opened their sitting punctually at ten o’clock, clearly shared this opinion. Francis Oakes, under oath, gave his testimony after John Macarthur’s name had been called and elicited no response. The judge advocate, miraculously restored to a semblance of sobriety, questioned him minutely as to Macarthur’s reaction to the serving of the warrant.

‘You say that Mr Macarthur told you that he intended to treat the warrant with the contempt which it and its author deserved?’

‘Yes, sir, them was his words. But ... ’ Oakes looked nervously about him, suddenly afraid that John Macarthur might, after all, be somewhere in the shadowed courtroom. God in heaven, suppose he was? Suppose he was listening, suppose ... but he was telling the truth, no one could blame him for that, surely?

The judge advocate, prompted by Crossley, went on relentlessly, ‘He said that he would ignore your damned—and I quote—your damned warrant, Mr Oakes?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Oakes confirmed, mopping his heated face. The bench consisted of Major Johnston, the corps commandant; Robert Campbell, the port naval officer; and John Palmer, the government commissary. He could read no sympathy in their grimly set faces although Major Johnston sought occasionally to interpose a question that might be said to favour his one-time comrade in arms.

‘Mr Macarthur said,’ Oakes managed, ‘that he had committed no crime, and that his conscience was clear. Sir, he—’

‘But he told you, did he not, that he declined to answer the summons to appear before His Majesty’s justices of the peace this morning, in order to answer the charges against him?’

‘That is so, sir, yes.’

‘And—think carefully, Mr Oakes,’ the judge advocate warned, ‘Mr Macarthur told you that if you came back for the purpose of enforcing the warrant, you had best—and again I quote—‘come well armed’.’

‘Them was his words. That I was to come well armed, for he’d not submit till blood was shed.’

‘They were words spoken in anger, surely?’ Major Johnston put in.

‘Oh, yes, sir, they were indeed,’ Oakes agreed eagerly.

‘Nevertheless those words show contempt for this court,’ Commissary Palmer pointed out.

‘As also does Mr Macarthur’s letter,’ Atkins said, with heavy emphasis. He read it aloud slowly and, having done so, looked across at the unhappy Oakes. ‘This letter was written in your presence, was it not, Mr Oakes? It was signed by Mr Macarthur in your presence?’

‘Aye, sir, I seen him pen it.’

‘He attempted to recover it from you, did he not, by sending his son after you to request its return?’

‘Clearly because he regretted having written in such terms in the heat of the moment?’ The intervention came from Major Johnston, and again Oakes assented gratefully.

‘But you refused to return the letter?’ Mr Campbell suggested, his tone curt.

‘I couldn’t give it back to Mr Edward, sir,’ Oakes answered, reddening. ‘Your honours might not have believed that I’d served the warrant if I’d let him have it back. I had to keep it, sir.’ Campbell, he saw, was smiling; Palmer, too, appeared pleased on hearing his admission, and the judge advocate said approvingly, ‘You acted correctly, Mr Oakes.’ He turned to face his fellow justices. ‘Gentlemen, I submit that John Macarthur is in contempt of this court and in clear defiance of the civil power of the colony of New South Wales. I ask you therefore to issue a second warrant authorising Mr Oakes, as chief constable of Parramatta, to take a party of armed constables to place him under arrest and lodge him safely in His Majesty’s jail, pending his appearance before this court.’

Oakes heard, with a sinking heart, their concerted assent. Even Major Johnston, stony-faced and unsmiling, raised no objection; the second warrant was signed and sealed and, drawing himself up, Oakes accepted it with what dignity he could muster.

‘You know your duty, Mr Oakes,’ the judge advocate bade him sternly. ‘Make diligent search for Mr Macarthur at once.’

The search was brief. John Macarthur made no attempt to conceal his presence in Sydney, and Oakes, with his armed party, found his quarry without difficulty at the house of the surveyor general, Charles Grimes. To his intense relief, Macarthur submitted without resistance, even making a rueful joke of it, and after a formal appearance in court, the bench of magistrates granted him bail, after committing him for trial at the next criminal court on 25 January, 1808. Bail was set at one thousand pounds.

2

Justin stood at the wheel of the Flinders cutter, completing his tack with the skill of long experience of the vagaries of the Hawkesbury River. His gaze, raised of necessity to the dingy canvas of his mainsail until he had brought the wind abeam, strayed—as of late it so often did—to the slim, beautiful girl standing a few paces from him.

Abigail Tempest had adjusted swiftly to conditions on board the cutter, taking an eager and intelligent interest in all that she saw and heard, and Justin, for his part, had been delighted to answer her questions concerning the farms and settlements they passed and the finer points of navigation, whenever an opportunity to do so presented itself. Not, he reflected a trifle resentfully, that such opportunities were frequent ... the Reverend Caleb Boskenna had seen to that.

The Flinders was crowded to the point of being overladen with Boskenna and his two young wards occupying the cabin space, the cutter’s holds crammed with government-issue tools and sacks of seed and provisions. Cookie Barnes and the three assigned convict labourers—as well as Justin himself—were compelled to bed down on deck when, during the hours of darkness, they came to anchor offshore. Boskenna’s horse and the half-bred Merino ram he had purchased from Captain Macarthur also had to be accommodated—the horse was in the forward hold and the ram in a makeshift pen amidships, where the dinghy was normally secured.

He had made repairs to the dinghy before leaving Hobart, but ... Justin glanced speculatively astern. He had not anticipated having to tow the patched-up craft all the way upriver to the Tempest holding, in order to load the bleating ram and its cage onto his spotless deck. But Caleb Boskenna had been arrogantly insistent, his concern for the apparently valuable animal equalled only by his determination to guard his two pretty little wards from all intercourse with their fellow passengers.

Boskenna, a sombre, black-garbed figure, stood at Abigail’s side, effectively cutting her off from Justin at the helm and frowning in disapproval whenever he observed the girl glance over her shoulder in his direction. Lucy, the younger sister, a pert, sly little creature, was permitted more freedom, but—unlike Abigail—she scorned to take advantage of it, treating him, Justin thought sourly, as if his status were little higher than that of the assigned labourers or Barnes, the cook, who was a ticket-of-leave man, serving a life sentence.

He watched her, letting the wheel slip through his strong brown fingers, as she emerged from the cabin hatchway and, carefully avoiding contact with the three convict labourers who were huddled together on the weather side of the hatch coaming, went skipping across to the Reverend Boskenna, her small face anxiously puckered.

‘Your horse, Mr Boskenna!’ Justin heard her exclaim shrilly. ‘It’s fallen down and doesn’t seem able to get to its feet, poor thing. I think you ought to look at it.’

Boskenna clicked his tongue in exasperation and glared angrily at Justin. ‘If that animal is injured, I shall hold you responsible, Master Broome!’

‘I am not responsible for your livestock, sir,’ Justin reminded him. ‘The Flinders is not equipped to carry horses, as I told you before we sailed. It was only on your insistence that I agreed to make an exception and take your horse but, you must recall, sir, entirely at your risk.’

He was on firm ground, and aware of this, Boskenna had to content himself with an irritable, ‘You are insolent, young man.’ Justin, unrepentant, suggested quietly, ‘I would advise you, sir, to see to the animal at once. A rope round its neck and hindquarters should suffice, with a couple of men to haul it up. If necessary, can rig a winch, but that would take time and delay us.’

Caleb Boskenna bit back an angry retort and, turning to his labourers, brusquely ordered them to follow him. The three—middle-aged men, with the hangdog air of those lost to hope and long since cowed by the ill-treatment they had met with since receiving their sentences—got to their feet and shambled obediently after him. Lucy, pleased by the stir her announcement had caused, whispered something to Abigail and went cautiously in pursuit, anxious to miss nothing of the excitement.

Abigail stayed where she was for a moment and then, gathering up her skirts, she came to Justin’s side. ‘Is it serious?’ she asked. ‘I mean, could that poor horse be badly hurt?’

Justin shook his head. ‘It’s unlikely—we had it pretty well secured. But there’s not much space in the for’ard hold. The animal will be better on its feet.’

‘You could put it ashore if you had to, I suppose?’

‘Yes,’ he agreed, ‘if we had to. As I told Mr Boskenna, I could rig a winch and lower the horse into the water—let it swim ashore. But it would hold us up ... and I’m aiming to reach your property before dark if this breeze keeps up.’

‘Are you so eager to be rid of us?’ Abigail questioned. She sounded hurt, and Justin reddened.

‘I try to complete my charters on time, Miss Abigail. And we’re overloaded. The Phoebe—the vessel your guardian originally hired—has more cargo and passenger space than my Flinders. I only accepted the hiring to oblige Mr Campbell.’

She eyed him in some bewilderment, and Justin’s colour deepened. She was so very pretty and charming, he thought, and fearing that he might unintentionally have offended her, he added quickly, ‘And because I realised that it would give me the chance to see you again.’

‘You did remember me, then?’

‘Of course I did! How could I forget? I—that night I called at Mrs Spence’s house and you came to the door in your party gown, you made such a picture, standing in the lamplight, I ... ’ Justin broke off, stammering in his embarrassment. To cover it, he spun the wheel, bringing the cutter’s head round and shouting to Cookie Barnes to haul on the weather jib-sheet. From below, a confused rumble and a stamping of hooves told him that the efforts of the Reverend Boskenna and his men had succeeded in restoring the horse to its safe upright position. This meant, of course, that the chaplain would be returning once more to the deck and that he would resume his all-too-strict chaperonage, thus precluding any chance of even the smallest conversational intimacy with Abigail Tempest.

It was one thing to reply to her questions in her guardian’s hearing, but he wanted to forge a link between himself and Abigail, Justin decided. Indeed he wanted—more than he had wanted anything for a long time—to bid for her notice, her friendship and perhaps even her feminine interest. He steadied the wheel, but Abigail dashed his newfound hope before he could find the nerve to put it into words.

‘Justin,’ she said, lowering her voice, ‘I am betrothed. That is, I have promised to marry Dr Titus Penhaligon, but Mr Boskenna does not know, and I ... well, I don’t want him to know ... not yet. I ... you will respect my confidence, will you not?’

Conscious of a swift pang of jealousy, Justin contrived to hide it behind a smile. ‘Of course I will, if that is your wish, Miss Abigail,’ he assured her.

‘I’ve told you, because I ... well, you see, I have a favour to ask of you,’ Abigail went on. She moved closer to him, and he caught a heady whiff of some faint, elusive fragrance that set his pulses racing. ‘You charter your Flinders, don’t you—regularly, I mean?’

‘Yes. That’s how I make my living.’ He started to explain, but she cut him short, hearing the Reverend Boskenna’s heavy footsteps on the hatchway ladder.

‘Dr Penhaligon—Titus—is at the Coal River settlement. They sent him there after poor Lieutenant Putland died, and I ... I have a letter for him. You go there sometimes, do you not—you go to Coal River?’

‘Yes,’ Justin confirmed. ‘I carry mail and prisoners there when the government gives me a charter. But I don’t know when I’ll next be given one.’

‘But you would know any vessel that was sent there?’ Abigail persisted. When he nodded, she slipped a hand into the bosom of her dress, withdrew a folded paper from it, and held it out to him. ‘Please,’ she begged. ‘Will you try to see that this is delivered, Justin, even if you cannot deliver it yourself? I would be so grateful to you if you would.’

It was, Justin told himself, at least something to earn her gratitude. The letter carried the fragrance of her person, and he took it from her, thrusting it into the pocket of his jacket as Caleb Boskenna stepped over the hatchway coaming, his dark, bearded face flushed from his exertions. He eyed Justin suspiciously for a moment, but Abigail had moved away from him and was now leaning over the lee-rail, apparently absorbed in contemplation of a cluster of settlers’ huts on the far bank of the river. The chaplain contented himself with a curt order to her to join her sister in the cabin.

He said irritably, in answer to Justin’s inquiry concerning the horse, ‘We got the unfortunate animal up, and it seems to have taken no harm. But the sooner we put it ashore, the better. When do you expect to reach our destination, can you tell me that?’

Justin grinned and gestured to a bend in the river a little over a mile away.

‘That’s Pimilwi’s Yoolong, Mr Boskenna. Once we round that, we’ll have the wind full astern, and I reckon we should be in sight of your place well before nightfall. If you are worried about your horse, I’ll winch it into the water as soon as we come to anchor, and it can swim ashore.’ He was tempted to add that the animal’s owner might accompany it if he wished, but Caleb Boskenna’s expression was such as to discourage levity, and instead he offered flatly, ‘If we make a start at first light tomorrow, it will not take above two hours to unload, with your men bearing a hand and so long as your jetty’s stout enough for me to tie up to.’

In fact, the unloading took even less time than he had estimated; the three convict labourers and the Reverend Boskenna himself, aided by the two men already there—the cook and the Cornish shepherd named Jethro—worked with a will. But Justin, anxious though he was to head back to Long Wrekin during the hours of daylight, was hurt and disappointed when, the last cask set ashore, Caleb Boskenna dismissed him with only a curt word of thanks. There was no invitation to visit the new farmhouse, no offer of a hot meal, and even more to his chagrin, he was afforded no chance to take leave of Abigail Tempest.

Mrs Boskenna, a thin-lipped, uncomely woman, took both girls with her to the house, and there they remained, hidden from Justin’s sight behind its shuttered windows. He did not catch so much as a glimpse of them even when he cast off from the wooden jetty and dipped his tattered ensign in formal farewell.

But it was a different matter when, late that same evening, he brought-to off the familiar wharf which served his mother’s and the neighbouring settlers’ farms and found Tom Jardine and William awaiting him, the former holding a lamp aloft to guide him in.

‘I saw you, Justin. I knew it was the Flinders when you were more than a mile away, and I told Tom it was you!’ William informed him excitedly, when he stepped ashore, ‘but Tom said it couldn’t be you, even if it was the Flinders, because he’d seen her going upriver yesterday morning, and if you’d been on board, you’d have come in here. You wouldn’t have gone sailing past Long Wrekin, Tom said. Why did you, Justin?’

‘I had a hiring—folk and cargo to deliver,’ Justin returned shortly. ‘But I’m here now, am I not?’ He hugged his young brother, and William, to his astonishment, clung to him in tears.

‘The lad’s missing his Mam,’ Tom put in, his tone defensive. ‘An’ it give him a turn, you sailing past yesterday, Justin. Me too, come to that. I didn’t rightly know what to think. We’ve been a long time without news, you know. Last we heard was that your Mam had been sent to Van Diemen’s Land in a transport from Norfolk Island.’

‘I’ve come to give you news,’ Justin said, ‘Willie, lad, your Mam’s fit and well—and she’s been pardoned! Captain Hawley had it straight from the governor the moment we landed in Sydney. And he and Mam are married—I saw the ceremony in Hobart. She—’

William’s face, which had grown perceptibly lighter with the news of Jenny’s pardon, had grown dark again as quickly, and now his cry of pain interrupted Justin.

‘You left her there!’ the boy accused bitterly. ‘You did not bring her back!’ He jerked his hand from Justin’s grasp and ran off into the darkness, sobbing as if his heart would break.

‘What the devil!’ Justin exclaimed, ‘How could I have brought her back if I didn’t know of the pardon until we reached Sydney? For the Lord’s sake, Tom, what has got into the lad? His Mam will be home soon enough, by the first available transport, the governor said.’

Tom Jardine shrugged his broad shoulders resignedly. ‘Like I told you, the lad’s been missing his Mam. Rachel, too, though maybe not so sorely as young Will has.’ He picked up Justin’s canvas kit-bag, hefted it onto his back, and jerked his head in the direction of the Long Wrekin farmstead. ‘My Nan’s got a meal waiting, and she’ll be better able than I am to tell you about Will ... he talks to her. But the land’s in good heart an’ the stock flourishin’, thanks to the help we’ve had from Mr Dawson an’ the other neighbours ... It’s such good news you’ve brought; the boy will come round, soon enough, don’t you worry. Your Mam will find everything in good order when she comes back, too.’ He hesitated, drawing in his breath sharply. ‘Could you say when she’d be cornin’, lad? It’d make such a difference to know—to the boy in particular, I mean.’

Justin’s mouth tightened.‘No, I can’t say when exactly, except that from what the governor told Captain Hawley, it will most likely be around the turn of the year. I myself had to come when I did—the governor had sent for Captain Hawley to come right away.’

‘That don’t surprise me,’ Tom returned, a hint of anger in his deep, countryman’s voice. ‘From all accounts Guv’nor Bligh’s headin’ for trouble, an’ he’s goin’ to need all the support he can command.’ Again he hesitated, and then added, in a hoarsely confidential whisper, ‘The Hawkesbury settlers are formin’ armed militia companies, Justin. I’ve joined, most of us have in this area.’

Justin halted, to stare at his dimly seen face in bewilderment. ‘In the Lord’s name, Tom—for what purpose?’