Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

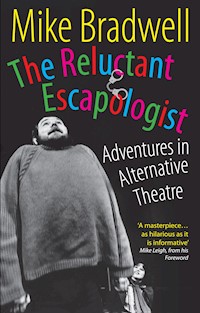

An unrivalled unofficial history of the rise – and partial fall – of fringe theatre, Mike Bradwell's deadpan account of his adventures is one of the funniest and angriest books to come out of theatre today. Winner of the 2010 Theatre Book Prize awarded by the Society for Theatre Research. As he travels through a counterculture peopled by nutters, chancers, dreamers and prophets, Bradwell makes us marvel at his resilience and creativity, captured in a succession of vivid – and often laugh-out- loud – episodes such as: creating a character with Mike Leigh; enjoying the onstage mass orgasms of The Living Theatre; eating fire with Bob Hoskins; becoming an underwater escapologist (reluctantly) in the Ken Campbell Roadshow; creating Hull Truck; and doing battle with the Health and Safety brigade, the funding bodies and a Polish heavy-metal disco during his ten years running the famous Bush Theatre in West London. Bradwell was a passionate champion of the alternative as well as an admired and successful director. In this book, he makes a compelling – and urgent – case for preserving the true and subversive spirit of theatre from castration at the hands of bankers, consultants, stakeholders, cultural-diversity compliance monitors and the Arts Council. 'Towards the end of this brilliant account of his epic forty-year journey, Mike tells us, 'I don't believe that theatre is safe in the hands of grown-ups', and it is his healthy, eternal youthfulness that makes the book so inspiring' Mike Leigh, from his Foreword

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 691

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Adventures in Alternative Theatre

Mike Bradwell

Foreword by Mike Leigh

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Foreword by Mike Leigh

Acknowledgements

Illustrations

Introduction

1. Games for May

2. Who Put the Cunt in Scunthorpe?

3. Hello Sadness

4. The Untameable Rhinoceros

5. High Windows

6. Hello Prestatyn

7. The Ghost of Electricity

8. Moving Swiftly On

9. Here Comes the New Boss

10. Same as the Old Boss

Postscript

Index

About the Author

Copyright Information

Here he is, in all his glory! Tough as an old scrotum, and soft as a baby’s bum, that unique, lovable mass of unhinged madness and profound sanity—Mike Bradwell himself, in appearance somewhere between Falstaff, Burl Ives and Winnie-the-Pooh—the magician of Shepherd’s Bush, and the inventor of the real Hull Truck. Guru, observer, critic, commentator, historian and chronicler of all things countercultural, and of our alternative theatre in particular, the ultimate outsider’s insider; poet, piss-artist, cynic and romantic; inspired director, writer and teacher; actor, fire-eater, vaudevillian, joker and jester; anarchist, exploder, debunker, activist, entrepreneur, visionary, fantast, dreamer, realist and surrealist; inspired manager and practical man-of-the-theatre; passionate nurturer of young talent, loved by generations of actors, writers, directors, designers and techies; partner, daddy, brilliant cook, loyal friend and consummate cheeky bugger… in short, your definitive reluctant escapologist, whatever that may be!!

Towards the end of this brilliant account of his epic forty-year journey, Mike tells us, ‘I don’t believe that theatre is safe in the hands of grown-ups’, and it is his healthy, eternal youthfulness that makes the book so inspiring.

Before I had read it, Mike asked me if I would consider writing a quotable supportive sentence. I wasn’t sure what would suit, so he suggested, ‘Buy this book. It is a work of genius. Laugh? I almost shat.’

Well, I’ve read it, and it gave me diarrhoea. It is as hilarious as it is informative. It is a masterpiece. Read it, and you too are guaranteed a truly moving experience.

Mike Leigh

London, April 2010

I would like to thank everybody who helped, informed and sustained me during the making of this book, especially Dudley Sutton, Chris Jury, Alan Williams, Mia Soteriou, Robin Soans, Philip Jackson, Dave Hill, Jane Wood, Sue Timothy, Tara Prem, Susannah Doyle, Matt Applewhite, Tim Fountain, Tony Bicât, Susanna Bishop, Natasha Diot and Jane Fallowfield. I would like to thank Catherine Itzen, James Roose-Evans, Jinnie Schiele, Julian Beck, Judith Malina, Abbie Hoffman, Peter Ansorge, John Tyrtell, Pierre Biner, Howard Goorney and Jean-Louis Barrault, whose books I pillaged on the way. I would like to thank Alan Plater and Kerry Crabbe for allowing me to quote from their plays. I would like to thank Nobby Clark, Gordon Rainsford, Sheila Burnett, Jonathan Player, Nicky Pallot, John Haynes, Jane Wood and Alastair Muir for letting me use their photographs. I would like to thank Chez Betty for the coffee and The Captain for the music. I would like to thank Nicola Wilson who made me keep going. And I would like to thank Helen Cooper and Flora Bradwell who were there every step of the way.

M.B.

*

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to quote extracts from the following:

‘Woodstock’ by Joni Mitchell, by kind permission of Alfred Music Publishing; AC/DC by Heathcote Williams (© 1972) and the Complete Works of Antonin Artaud, translated by Victor Corti (© 1971), by kind permission of Calder Publications (UK) Ltd; ‘Les bourgeois’ by Jacques Brel, by kind permission of Éditions Jacques Brel; ‘High Windows‘ from High Windowsby Philip Larkin (© 1974), published by Faber and Faber Ltd; Joan’s Book: Joan Littlewood’s Peculiar History As She Tells It by Joan Littlewood (© 1994), and Towards a Poor Theatre by Jerzy Grotowski (© 1968), both published by Methuen Drama, an imprint of A&C Black Publishers Ltd; The Theatre Workshop Story by Howard Goorney (© 1981), published by Methuen Publishing Ltd; Four Plays by Conor McPherson (© 1999), published by Nick Hern Books Ltd; and ‘The Bird of Paradise’ from The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise by R.D. Laing (© 1967), published by Penguin Books Ltd.

Mr Pucci at the Roundhouse, 1969

Bleak Moments by Mike Leigh, 1971

Poster for Improvised Play No. 10 by Mike Leigh, Open Space Theatre, 1970

Poster for Hirst’s Charivari on Southsea Common, 1971

Hirst’s Charivari, 1971 (photos: Jane Wood)

The original Hull Truck company, 1972 (photo: John Valentine)

Flyer for Children of the Lost Planet, Hull Truck, 1972

The Weekend After Next, Hull Truck, 1973 (photo: John Valentine)

The Knowledge, Hull Truck, 1974

Granny Sorts It Out, Hull Truck, 1974

Oh What!, Hull Truck, 1975 (photo: Nobby Clark)

Bridget’s House, Hull Truck, 1976 (photo: Nobby Clark)

The Bed of Roses company, Hull Truck, 1977

The Great Caper by Ken Campbell, Hull Truck, 1978

The New Garbo by Doug Lucie, Hull Truck, 1978 (photo: Charlie Waite)

Mean Streaks by Alan Williams, Hull Truck, 1980

Games Without Frontiers, BBC TV, 1980

Still Crazy After All These Years, Hull Truck, 1981 (photo: Nobby Clark)

Bad Language by Dusty Hughes, Hampstead Theatre, 1983 (photo: John Haynes)

Hard Feelings by Doug Lucie, Oxford Playhouse and the Bush, 1983 (photo: Nicky Pallot)

Unsuitable for Adults by Terry Johnson, Bush, 1984 (photo: Nicky Pallot)

Meeting the Crown Prince and Princess of Japan, Tokyo, 1982

Filming Happy Feet, Scarborough, 1989

Flann O’Brien’s Hard Life by Kerry Crabbe, Tricycle Theatre, 1985 (photo: Sheila Burnett)

Love and Understanding by Joe Penhall, Bush, 1997 (photo: Alastair Muir)

Shang-A-Lang by Catherine Johnson, Bush, 1998

Howie the Rookie by Mark O’Rowe, Bush, 1999 (photos: Alastair Muir)

Resident Alien by Tim Fountain, Bush, 1999

Blackbird by Adam Rapp, Bush, 2001 (photo: Raphie Frank)

The Glee Club by Richard Cameron, Bush, 2002 (photo: Gordon Rainsford)

adrenalin… heart by Georgia Fitch, Bush, 2002 (photo: Gordon Rainsford)

A Carpet, a Pony and a Monkey by Mike Packer, Bush, 2002 (photo: Gordon Rainsford)

Crooked by Catherine Trieschmann, Bush, 2006 (photo: Alastair Muir)

Outside the Bush, 1997 (photo: Jonathan Player)

Every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge the owners of the various pieces of material in this publication. Should the publishers have failed to make acknowledgement where it is due, they would be glad to hear from the respective owners in order to make amends.

This book tells the tale of the two theatre companies I have run: Hull Truck from 1971 to 1982 and the Bush Theatre from 1996 to 2007—and of the people who inspired me to run them in the way that I did. It also offers in part, a partial, personal and totally biased history of alternative theatre in Britain over the last forty years or so, and of its part in my downfall.

I subscribe to the ‘Shankly Protocol’. I believe that theatre is not a matter of life and death; it’s much more important than that. Real theatre must have the same dirty, corruptive influence as rock ’n’ roll. Real theatre must be sexy, subversive, dangerous and fun, and in constant opposition to the Establishment. The day the music died was not the day that Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper were killed in the plane crash. The music died on the day that Elvis joined the US Army.

I believe that a functioning theatre is as important, and as necessary, to the spiritual and physical well-being of any community, as a school, a hospital, a police station, a library, a sports centre or a prison. The essential bargain of theatre is that a group of human beings get together with another group of human beings and collectively they try to find ways to enrich the experience of being human. The theatremakers that I most revere all appear to believe this too.

Joan Littlewood and her Theatre Workshop company constantly sought to make popular, provocative and radically political entertainment for the widest possible audience. Julian Beck, Judith Malina and The Living Theatre wanted theatre to be become the revolution itself. They demanded ‘Paradise Now’ and would accept no substitute. Mike Leigh, through his unique improvisation techniques, took truth and honesty in acting on to a higher plane and made, and continues to make, some of the most compassionate drama of all time. And Ken Campbell was the visionary embodiment of the Great God Pan, for ever searching for the most astonishing, remarkable and mind-bending caper of them all. Together they have inspired generations of directors, actors and writers and hopefully they will continue to do so for many years to come.

Apparently we are now living in a new theatrical golden age. The West End is booming. New classless audiences are flocking to the National Theatre, courtesy of the Travelex £10 ticket scheme. Subsidised non-elitist playhouses in both London and the regions offer a cornucopia of multicultural diversity and popular, yet challenging entertainment. There is, we are told, a renaissance in playwriting. There are more new plays being performed than ever before, with thrusting new writers appearing, and being celebrated daily. Some of them are even women, a couple of whom are so especially talented that they have been allowed to play in the biggest boys’ playground of them all—the Olivier Theatre. Exciting performance and site-specific groups are springing up in catacombs and abandoned glue factories everywhere. The theatre god is in her heaven and all is right with the world.

An alternative version might be that the whole thing is a cosy conspiracy of mediocrity perpetrated by a circle jerk of Oxbridge directors, venal producers and supine middle-aged, middle-brow and middle-class dead white male critics foisting their suspect and overhyped metropolitan taste on the long-suffering, culturally browbeaten theatregoing public. The West End is sagging with Sixties musicals whose popularity is boosted by millions of pounds’ worth of free reality-TV advertising, bought and paid for by licence-fee payers, and dedicated to helping Andrew Lloyd Webber or Cameron Mackintosh find a new Nancy.

Both commercial and subsidised boutique theatres continue to offer marketing-friendly event theatre: tricked-out and often anodyne revivals both classical and modern, stuffed with British and American film stars and directed by high-flying, high-profile movie directors.

Whichever of these views you subscribe to there is, however, one undeniable statistic, and that is that, in the last twenty-five years, the biggest single area of growth in theatre, and indeed most other walks of life, has been in the relentless expansion of the administrative and entrepreneurial classes. Indeed it seems that the history of the last fifty years of British theatre forms a perfect arc. The first twenty-five years were devoted to the struggle of artists and practitioners to get their hands on the means of production. The second twenty-five were spent watching management and executive claw them back. Such was the increase in administrative personnel that theatres have had to build extra floors to cope with the new departments overrun with chief executives, corporate events coordinators, marketing managers, diversity-compliance monitors, development consultants, finance officers, risk assessors and their myriad staff, all of whom believe that their worth in the marketplace is much greater than that of the artists whose endeavours their jobs were created to support. Theatre boards are stuffed with bankers, wealth creators and similar parasites recruited from the crime scene that is the City of London and who readily endorse the overblown salary claims. It is now common practice for individuals to be paid more to advertise a play than to write one. This has got to stop.

Joan Littlewood’s old theatre, the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, currently has a full- and part-time staff of eighty-six before you even get to the creative personnel. In 1959, apart from Joan, the Theatre Workshop company had an entire administrative staff of three, although Mrs Chambers and Mrs Woolmer shared the cleaning duties, and many different wines, beers and spirits could be had from Mrs Parnham in the Long Bar, and tea, coffee, chocolates and snacks were available from Mrs Murphy in the snack kiosk. And this was at the same time as they were producing A Taste of Honey, The Hostage and Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be.

The extent to which even alternative theatremakers have rolled over and become complicit in all this corrosive practice is well illustrated by the case of one London profit-share fringe theatre that boasts two Artistic Directors, two Programming Directors, a Development Director, a Development Coordinator, three Development Officers, two Marketing Officers, a Head of Press, two Education-project Directors, a Youth-leader Project Manager, and at least a dozen other odds and sods. One imagines that there is not much profit left to share with the writers, directors and actors after this lot have had their cut. Maybe they believe that, by having them all, they will be able to attract Arts Council subsidy, in the same way that primitive tribes in New Guinea used to build crude wooden models of televisions, aeroplanes, fridges and the like in the hope that the gods would send them the real stuff. In the first two years of its existence the Bush Theatre mounted seventy-seven productions with a combined artistic, technical and administrative staff of just two.

And has all this freebooting expansionism resulted in better theatre? I seriously doubt it. What has happened is that the preoccupation with market efficiency and economic growth has begun to subordinate all other values. Morality, truth and honesty have no market price and are therefore considered to be almost irrelevant. Theatre development departments, in constant search for more sponsorship, compete with each other to climb into bed with the most unsuitable commercial organisations. Does anyone really believe that Shell underwrote the National Theatre Connections Scheme because of an overwhelming desire to encourage Mark Ravenhill or Simon Bent to write pithy new drama for teenagers? Surely the transaction is an attempt by Shell’s PR department to gussy up their tarnished image as one of the planet’s leading environmental polluters. And might not a value-added bonus be that no Executive Producer or CEO would be likely to allow the production of a show that, for example, might suggest that Shell were allegedly complicit in the arrest and execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian environmental activist? You don’t bite the hand that feeds you.

Even more worrying is that, these days, it seems that even the most radical theatremakers would prefer to find themselves safely tucked up inside the glittering Kunstpalasts of Establishment Theatre pissing out, rather than outside them pissing in. They seem to be keener to allow themselves and their wares to be trafficked into the tawdry brothels of the West End and the subsidised temples of consensus culture, rather than to conspire to tear them down. Maybe it’s all to do with school fees.

The current financial meltdown means that there are likely to be swingeing cuts in public expenditure for many years to come. Whichever government is in power, the subsidised arts seem to be in for a kicking. Even the future of the Arts Council itself is uncertain. Faced with much-reduced budgets it is to be hoped that theatres use this as an opportunity to shed all the surplus layers of overpaid and unnecessary executives, administrators and consultants, rather than reduce the money spent on the art. I doubt that this will be the case. Similarly I suspect that the big organisations like the National Theatre, the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera House will remain untouched while small radical and experimental companies will, as usual, bear the brunt of the cuts.

If this book has any purpose it is to remind theatremakers that it is possible and even desirable to make their theatre outside the warm embrace of the theatrical Establishment, either commercial or subsidised. Between 1966 and 1974 over two hundred itinerant alternative theatre companies sprung up all over Britain, presenting entertaining, provocative and incendiary new work throughout the country. Perhaps the time had come to go on the road again.

In the early days of punk, the fanzine Sideburns published a drawing of three guitar chords with the caption:

Here’s a chord. Here’s another. Here’s a third. Now form a band. My version would go:

Find a play. Squat a building. Steal a van. Now make a show.

We may indeed be living in a new golden age of theatre, but even if we are, I would still like to think that, lurking in a dark alleyway round the back of every new £15 million glass-and-steel culturally non-elitist Shopping Mall Playhouse and Corporate Entertainment Facility, is a gobby and pretentious twenty-year-old with a passion for real theatre, a can of petrol and a match.

The Reluctant Escapologist is dedicated to all those who think that they should have been in it, and equally to all those who are glad to discover that they are not.

On 12 May 1967 I went to a concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The Pink Floyd were performing Games for May—A Space Age relaxation for the climax of spring. The Floyd at that time was very much Syd Barrett’s band, and they and psychedelia were about to become big. Mark Boyle did the liquid-light show, and there was, for the first time anywhere, a rudimentary quadraphonic sound system. They played all Syd’s songs: ‘Interstellar Overdrive’, ‘Astronomy Domine’, ‘Arnold Layne’, ‘Bike’ and ‘See Emily Play’. They played a toy xylophone, a rubber duck and a hacksaw. There was a bubble machine and flower children. I sat on the front row. A man dressed up as an Admiral gave me a daffodil. I psychedelically ate it. Go with the flow…

After the gig I went to the UFO Club in Tottenham Court Road and saw a mediocre R-and-B band called The Paramounts magically transform themselves into Procol Harum to play their new song ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ for the first time in public. Earlier that day I had auditioned for East 15 acting school. I did a speech from David Halliwell’s Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs: the bit where Nipple goes down Leeds road t’ gasworks and describes it as ‘a surreal kaleidoscope pageant of insubstantial seemin’ ’. I ended up under a chair.

Because I had had a haircut for the audition the guy on the door at UFO thought I was the pigs.

Next morning I staggered out into the grey London dawn tripping the light fandango and doing cartwheels across the floor and then hitched back to Scunthorpe. It took me two days.

When I got home there was a letter to say that I had been accepted at East 15 for a place on the Directors’ Course. I had to turn up in October with tights, a fencing mask, a cape, a pair of wellington boots and a copy of Onions’s Shakespeare Glossary.

East 15 was the only drama school I had applied to, partly because it was the only place I thought would let me in, partly because the adverts said they were looking for ‘lively minded, argumentative, inventive, exquisite, vulgar, idealistic, talented students who want a livelier theatre’, but mainly because of Joan Littlewood.

At the Edinburgh Theatre Conference in 1963, when Ken Tynan, John Calder and Jim Haynes had staged the first happening in the UK, experimentally pushing a nude woman about in a wheelbarrow, Joan had famously declared that ‘all drama is piss-taking and we are all here to take the piss’ which had impressed me enormously. Also I had joined the Young Communist League and Youth CND at the age of fourteen, and I had heard that she was both a Pacifist and a Communist.

I had seen her groundbreaking production of Oh What a Lovely War in the West End and knew something different was going on. The actors had a quality I had never seen in Rep. They were real. They could dance and they could sing and they talked to the audience not at them. They seemed to own the show and could move from comedy to tragedy at the drop of a hat, and I wanted to know how they did it. Like everyone else I had heard stories of how Joan worked with improvisation on this, and other productions like The Hostage, Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be and A Taste of Honey. Improvisation was pretty much derided at the time by actors and directors who were both sceptical and scared of it, probably because very few people knew what it was or how to do it. I was also intrigued to read of Bill Gaskill’s attempts to get Olivier to improvise during rehearsals for The Recruiting Officer at the National. It seemed to me to be risky and revolutionary, and East 15 was the place to find out about it.

I had always wanted to work in theatre. My father, a Lincolnshire farmer, had a love of variety and circus, and as child I saw great comedians like George Formby, Jewel and Warriss, Norman Evans, Tommy Cooper, Tony Hancock, Chic Murray, Jimmy Clitheroe, The Crazy Gang and the best of them all, Jimmy James. He even took me to see Buddy Holly and the Crickets live on stage at the Doncaster Gaumont, watching askance as the Teds jived in the aisles. My sister became a baby ballerina doing Panto with the Christine Orange Pippins, and I got to work backstage in the school holidays eventually becoming a student ASM at Lincoln Theatre Royal (where Michael Billington was Publicity Manager) and at Scunthorpe Civic Theatre. From the age of fifteen I worked as a stagehand on everything from Pinter to Puss in Boots and I saw and read as many plays as I could. I was inspired by Chekhov and his declaration that he made theatre in the hope of influencing audiences to make a new and better life for themselves. Later I was excited by Peter Brook’s Theatre of Cruelty experiments at LAMDA and by the Marat/Sade at the Aldwych. Productions of Edward Bond’s Saved at the Royal Court and Halliwell’s Little Malcolm made me realise that theatre had a duty to provoke as well as to entertain and that it could and should be as exciting as rock ’n’ roll.

In 1966 I left school, saw Dylan go electric at Sheffield City Hall and joined the newly founded Scunthorpe Youth Theatre. Oddly enough, the first time I had been called on to improvise was at my audition, when director Philip Thomas asked me imagine myself to be an old Jew whose house is burning down. We did a production of the Appalachian witchcraft play The Dark of the Moon, which the local newspaper the Star described as ‘an important step forward in the weaving of the cloak of cultural maturity towards which Scunthorpe has so long aspired’.

Phil Thomas was a local Drama lecturer and an inspiration to many. After the production a few of us went up to the Edinburgh Festival in his old Mini, driving through the night. We saw ten shows in two days, including the original Oxford student production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. Philip thought it was a wank. At the old Traverse on the Lawnmarket we saw plays by Arrabal and Heathcote Williams and were inspired by Liverpool poet Adrian Henri, who was dressed up as Père Ubu.

Phil insisted I apply for drama school, but first I signed up to do an Economics course at Doncaster Technical College, possibly because the LSE at the time was a hot bed of radical student action and I thought Doncaster Tech might be too.

This was a big mistake. I spent a miserable winter sitting in the college refectory with fellow students John Lee, who was to be a founder member of Hull Truck, and Richard Cameron, now an important playwright. We were like Scrawdyke and the Dynamic Erection Party in Little Malcolm, planning the overthrow of civilisation and trying to pull secretarial students on day release from the Yorkshire Coal Board over endless plates of beans and chips. We also joined the Doncaster Poetry Society and got to listen to Roger McGough, Seamus Heaney, Hugh MacDiarmid and Adrian Mitchell. We planned to take a satirical review to Edinburgh but never got round to writing it. I briefly fantasised a career as a sensitive contemporary folk singer/songwriter and hung around Scunthorpe Folk Club for a while in the vain hope of being invited to sing. All of which was getting me nowhere. In London the Counter Culture, inspired partially by the legendary Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and Corso gig at the Albert Hall in 1963, was starting to get itself together with the birth of the underground newspaper International Times, the UFO club and the Indica Gallery where John met Yoko. And theatre was at the heart of the movement. At the Freak Out organised to launch International Times at the Roundhouse, Peter Brook’s RSC actors turned up with the express intention of sorting out Charles Marowitz, who had accused them of failing to take sides in their production of US. In Europe the exiled Living Theatre had begun to work on their adaptation of Frankenstein through ‘impassioned discussions and psychedelic improvisations’. And who exactly was Grotowski and what did he do?

Sitting in the Doncaster Tech College canteen I had scant opportunity to see the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, and I was hardly likely to. I applied to East 15. I had realised that if you work in theatre you can really piss off grown-ups, and if you’re lucky you might get a shag.

The Summer of 1967, the Summer of Love. ‘Tune In. Turn On. Drop Out.’ In San Francisco the Beats became Flower Children and held the first Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park. To a soundtrack of the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters handed out tabs of Owsley’s best LSD at the Acid Tests. Jimi Hendrix blew everyone away at Monterey. Protest against the Vietnam War grew. The San Francisco Mime Troupe made radical street theatre as students burnt their draft cards. In New York 700,000 marched on the United Nations. Abbie Hoffman and his Guerrilla Theatre Situationists invaded the Stock Exchange, burnt dollar bills and declared the end of money. Antonin Artaud’s demand for ‘the poetry of festivals and crowds with people pouring into the streets’ seemed to be coming true.

‘If you’re going to San Francisco be sure to wear some flowers in your hair.’ If you were going to Scunthorpe High Street such a manoeuvre would be singularly ill-advised. Where I come from you were considered queer if you used adjectives.

I spent the Summer of Love playing Azdak in the Youth Theatre production of Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle, trying to grow a beard and get into Grusha’s knickers. I walked about wearing a policeman’s cape, Indian beads and a ten-gallon hat from a junk shop, and bored everybody shitless banging on about Timothy Leary. Psychedelic drugs were totally non-existent, and so I experimented with smoking dried banana skins—‘electrical banana is going to be the coming phase’—crushing up morning glory seeds and snorting foxgloves. ‘Make Love Not War’ was the order of the day but free love had, as yet, sadly failed to find its way up north. Richard Cameron maintains that it was not until the mid-Eighties that you could get into a girl’s brassiere in Doncaster without putting down a deposit on a council house.

At the Edinburgh Festival I saw a Swedish marionette version of Ubu Roi and the Traverse production of Ubu Enchaîné. I slept under the Forth Bridge. I bought a copy of Artaud’s Theatre and Its Double. I saw Café La MaMa doing Tom Paine and the Soft Machine performing Lullaby for Catatonics with Mark Boyle’s Sensual Laboratory and the Epileptic Flowers, two experimental danseuses who experimentally shagged a beach ball.

Most remarkable of all was Jean-Claude Van Itallie’s America Hurrah, performed by Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theatre. The three short plays Interview, TV and Motel were a direct attack on America and the American way of life. They were angry and violent and uncompromising, and they tackled everything from consumerism to the Vietnam War head on. Motel ended with the actors dressed as grotesque carnival dolls, representative of Middle America, trashing a motel bathroom and daubing slogans on the walls to the sound of heavy-metal feedback. I enthusiastically fantasised running a guerrilla theatre troupe that broke into people’s homes, smashed up their TV sets and forced them to watch significant political drama. ‘Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers.’

On 8 October 1967 I set off with my leotard, wellington boots and Onions’s Shakespeare Glossary for East 15. I believed that theatre could change the world… and I still do.

Joan Littlewood founded Theatre Workshop in Manchester in 1945 with Ewan MacColl, Gerry Raffles, Rosalie Williams, John Bury and Howard Goorney. Joan and MacColl had worked together before the war in the Workers’ Theatre Movement and Theatre of Action. They performed Socialist agitprop theatre and their influences were Meyerhold, Piscator, Commedia dell’Arte and subsequently Stanislavsky and Rudolf Laban. For their pains they managed to get themselves blacklisted by the BBC for Communist sympathies.

Theatre Workshop was very much an ensemble company and functioned as a collective. Joan preferred to work with actors who didn’t look or think like actors, and would have nothing to do with the ‘calcified turds’ of the Repertory or the West End. She believed in constant training and in stretching the company by doing daily voice and Laban movement classes: discipline unheard of in British theatre at the time. They experimented with European design and lighting techniques. They studied classical texts including Aeschylus, Sophocles and Aristophanes. They initiated and researched contemporary projects. They worked on ways to combine Stanislavsky naturalism with Meyerhold’s expressionism, British music hall and taking the piss. They designed and built the sets, made the costumes, put up the posters and sold the tickets. They borrowed and they blagged and they travelled in an old lorry playing wherever would have them. They were frequently broke. The Arts Council would not fund them because of their politics, so they all took part-time jobs to pay for the shows. Sometimes they picked tomatoes and sold them round Manchester from a barrow. Sometimes they had to sing for their supper. They often lived communally, sharing what food they had. They were trying to make genuine, popular, socially relevant, entertaining theatre for the people.

Their repertoire drew on the European classics including Molière, Lorca and Lope de Vega, Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, and Ewan MacColl’s own plays, notably Uranium 235: a protest piece about the hydrogen bomb. Gradually they evolved their own style and began to find an audience. Gradually their unique work began to be recognised, but not by the critics. The company toured Czechoslovakia, Scandinavia and throughout Britain. They gate-crashed the Edinburgh Festival. Joan always maintained that the term ‘fringe’ was invented to describe their unofficial Festival appearance. They were frequently homeless, but they had an early champion in the form of the colourful queer Socialist MP Tom Driberg, who also wrote the William Hickey gossip column in the Daily Express. Driberg let the nomad troupe camp and rehearse in the grounds of his home, Bradwell Lodge in Essex, where they also ran workshops and summer schools. He even wrote a play for them.

In 1953 the company moved into the Theatre Royal, Palace of Varieties, Stratford, London, E15. ‘Ours is Chaucer’s Stratford, rather older than Will’s,’ said Joan. They hired it for twenty quid a week. The move caused a schism in the company. Ewan MacColl thought they were betraying their roots and soon drifted off to spearhead the British Folk Music revival. The company lived in the dressing rooms and cooked in the Gallery bar while they presented fortnightly Rep. They kicked off with Twelfth Night, hoping to attract a local audience from the market in Angel Lane. Hardly anybody came, but over the next couple of years they gave them everything from Shakespeare, Shaw and O’Casey to Hindle Wakes, Celestina and The Alchemist. They worked eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, fuelled by strong tea and Benzedrine. The company believed that only the best was good enough for the people but the people stayed away. A whole bunch of new actors joined, including Dudley Sutton, Brian Murphy and Yootha Joyce, who also ran the box office. Richard Harris and Maxwell Shaw walked in off the street. All were rigorously schooled in Workshop techniques. Slowly the word got around and audiences ventured out to Stratford East. When Joan produced a memorable Richard II with Harry H. Corbett, even the critics plucked up the courage to risk the arduous journey to the wastelands at the far end of the Central Line. Unsupported by the Arts Council, who still thought they were a bunch of Commies, and to the chagrin of the theatrical Establishment, the company were invited in 1955 to represent England at the Théâtre des Nations in Paris. Lacking funds for transport costs they were offered money by a West End impresario in exchange for a hefty poster credit. Joan told him to fuck off. The actors took the ferry, carrying the set, props and costumes for Arden of Faversham and Volpone with them.

Back home Joan played Mother Courage in the British premiere of Brecht’s play. Brecht would only grant permission for the production if she took the part. Gracie Fields, who was his first choice, wasn’t available. Joan was reluctant to do it, and apparently she was terrible. Despite her work being constantly labelled as Brechtian, Joan was never a big fan. She thought he was humourless. ‘I hate the cunt,’ she once said.

In 1956 Theatre Workshop produced The Quare Fellow, Brendan Behan’s extraordinary anti-capital-punishment prison play. Joan and the company fashioned the piece from Behan’s wild and chaotic text. The result was revolutionary. The Quare Fellow opened in the same month as John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court, and these two productions arguably changed British theatre for ever.

Whilst it is impossible to determine whether Theatre Workshop or The English Stage Company had the greater influence on future theatre practitioners, it would nonetheless be true to say that, whereas the Royal Court concentrated on producing important plays, Stratford East made socially significant popular theatre and had better jokes. Despite Joan’s lifelong distaste for the glittering shithouse of the West End, the company were broke, so The Quare Fellow transferred to the Comedy Theatre, where it ran for three months.

The next year Joan, Gerry Raffles, designer John Bury and actor Richard Harris were taken to court by the Lord Chamberlain, charged with wilful improvisation. The play that caused the trouble was Henry Chapman’s You Won’t Always Be On Top. The play is set on a building site, so Bury had transformed the theatre into one, with the actors mixing real concrete and laying real bricks. There had been the usual improvisation during rehearsals, but this continued organically into performance, thus deviating from the text that had been licensed by the Lord Chamberlain, who sent in spies. They reported the company for criminal deviation, contrary to the Theatres Act of 1843.

In a sequence involving the opening of a public lavatory Richard Harris illegally impersonated Sir Winston Churchill while appearing to take a piss. If the company lost the case there was a chance that the theatre might be closed down. The Workshop managed to get a top-notch barrister to act for them for free. Fortunately the presiding magistrate, who had been a builder by trade, liked the play. He fined them fifteen pounds and told them not to do it again, and the Lord Chamberlain was made a laughing stock for bringing the charges. It would be another decade before the ludicrous farrago of state theatre censorship was done away with, but his Lordship had not yet finished with Joan.

Brendan Behan, after drinking his commission fee and after being motivated at gunpoint by Gerry Raffles, had managed to write sufficient of The Hostage for the company to go into rehearsals. They pieced together the play from improvisation, Brendan’s anecdotes and rebel songs, and created an anarchic Commedia masterpiece populated by hookers, nutters, ne’er-do-wells, drag queens and the IRA. Brendan, often in the audience and often drunk, often joined in the show. The Lord Chamberlain reluctantly licensed the script after demanding that ‘the builder’s labourer is not to carry the plank in the erotic place and at the erotic angle that he does, and the Lord Chamberlain wishes to be informed of the manner in which the plank in future is to be carried’.

Joan, in homage to the comrades in Sloane Square (she called them the living dead), inserted a sequence in which the two most boring characters in the play were unceremoniously stuffed into a dustbin marked ‘Return to the Royal Court Theatre’. The English Stage Company was giving its Endgame at the time.

Shelagh Delaney was nineteen when she wrote A Taste of Honey. She had been taken to a Rattigan play at Manchester Opera House and had been sufficiently inspired to write her own. Although the style was naïve, the use of language was electric, and Joan spotted the talent straight away. She produced the play, again with improvisational input into the script from the company.

The plot is simple, but the story of a teenage girl first made pregnant by a black boyfriend who deserts her, and then cared for by a gay art student, was groundbreaking for the time. The Arts Council, waking up to what was going on, gave Theatre Workshop a grant of £150 towards the production but demanded ten per cent of all future profits from the play in return. Against Joan’s better judgement both The Hostage and A Taste of Honey transferred to the West End.

After fifteen years the company had become an overnight sensation. Their new-found fame brought a new set of problems, and several actors were lured away by lucrative offers from the commercial theatre and television. Joan was desperately juggling three separate casts, two in the West End and one back at Angel Lane. The situation was further complicated with the arrival of Frank Norman’s play, Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be.

Norman was an ex-con, whose abrasive novel Bang To Rights had been celebrated by the glitterati. Joan decided that Fings should be a musical and roped in Lionel Bart, a musical prodigy from Stepney who had once been a member of Tommy Steele’s backing group The Cavemen and had written Cliff Richard’s catchy number-one hit ‘Living Doll’. Joan turned the script inside out, and the actors added new scenes and dialogue with Frank and Lionel joining in the improvisations and writing new songs on the hoof. Fings was a triumph and for the first time the theatre was packed with people who had never been to the theatre before, including cockney villains revelling in the celebratory tale of cockney villainy. Max Bygraves took a heavily sanitised version of the title song to the top of the charts, and soon the nation was singing about how ‘Once our beer was frothy but now it’s frothy coffee’, rather than how ‘Once in golden days of yore ponces killed a lazy whore’, reducing Bart’s hymn to the glories of prostitution to a bit of a generational nostalgic moan. Fings went straight into the West End. The Hostage went to Paris and Broadway. A Taste of Honey was to be made into a film. Brendan had become a household name, and his Rabelaisian antics filled the gossip columns. Joan sensed trouble ahead. ‘Success is going to kill us,’ she said.

She had to cast and train another company for Make Me An Offer, the Wolf Mankowitz musical set down the Portobello Road. She recruited Roy Kinnear, Sheila Hancock and Victor Spinetti, who was doing stand up in a strip club. Despite Mankowitz’s reluctance to change a word of his script, the show was a success, as was Stephen Lewis’s Sparrers Can’t Sing with Barbara Windsor. Both shows made the journey up west, making a total of five transfers in two years.

‘They will soon be naming the junction of Charing Cross Road and Coventry Street, Littlewood Corner,’ wrote Bernard Levin.

It was all too much. Joan was exhausted and felt that the company’s standards were being eroded and that the work, which soon came to be caricatured as a cheeky, cockney, nostalgic knees-up, was a far cry from the original Socialist blueprint set down in 1945. The Arts Council still wouldn’t subsidise the company—between 1945 and 1961 they gave them less than £5,000—and they were still demanding their ten per cent royalty for A Taste of Honey.

‘When you have to live by exporting bowdlerised versions of your shows as light entertainment for sophisticated West End audiences you’re through,’ said Joan in 1961, and she quit and went off to Nigeria. She returned in 1963 to direct Oh What a Lovely War, possibly her greatest triumph.

Gerry Raffles had heard a radio broadcast by Charles Chilton combining the verbatim testimony of the soldiers in battle with the jingoistic songs of the First World War. He commissioned a script. Joan threw it out, put together a company of Workshop regulars and started again. The cast was initially unimpressed with what they thought was the sentimentality of the songs, but, by juxtaposing them with the terrible statistics of the war dead and naturalistic scenes showing the reality of life in the trenches, they created a bitter satire on the sheer waste and incompetence of the Capitalist war machine and a moving tribute to the lives that were needlessly sacrificed. Add to this Joan’s brilliant device of presenting the entertainment as a seaside Pierrot Show while coldly projecting details of the casualties on a moving news panel and you have a production that horrifies, moves, offends and entertains the audience in equal measure. It was the culmination of everything Theatre Workshop had striven for. The final message of the futility of war and the politics that cause wars chimed with the British audience still affected by the Cuban missile crisis. Arguably the show contributed to the growth in support for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Oh What a Lovely War ran for over a year in the West End and then went round the world. Forty-five years later it is performed regularly, particularly in schools and by youth theatres and, although frequently and misguidedly accused of sentimentalism, it has nonetheless become one of the important political plays of the twentieth century.

The Fun Palace was a dream that Joan had cherished for years. She had been inspired by the eighteenth-century Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens and wanted to create a twentieth-century version on the Isle of Dogs. Here there would be plays, music, clowns, diversions, dancing, eating, drinking, arts and crafts, raree shows, charivari, fireworks and general rollicking. Partly educational, partly recreational, the Fun Palace would be a cultural amusement park for the People. A contemporary William Morris utopian playground:

In London we are going to create a university of the streets—not a gracious park, but a foretaste of the pleasures of the future. The Fun Arcade will be full of games that psychologists and electronics engineers now devise for the service of industry, or war. Knowledge will be piped through jukeboxes. In the music area—by day, instruments available, free instruction, recordings for everyone, classical, folk, jazz, pop, disc libraries—by night jam sessions and festivals, poetry and dance.

In the science playground/lecture demonstrations, supported by teaching films, closed circuit television and working models, at night an agora or Kaffeeklatch where the Socrates, Abelards, Mermaid poets, the wandering scholars of the future—the mystics, sceptics and sophists—can dispute till dawn. An acting area will afford the therapy of theatre for everyone.

Joan enthusiastically set out to raise money for the development of the Fun Palace despite the project being lampooned in the press as some kind of Littlewood cheeky-chappie, cockney theme park—all jellied eels, pearly kings and doing the Lambeth Walk. She made a film version of Sparrers Can’t Sing, which featured the Kray Twins’ henchmen and a bunch of local faces as extras. She made a few commercials, and she agreed to direct what was supposed to be a West End blockbuster musical.

In the short years since Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be, Lionel Bart had become a household name and the most successful musical-theatre composer in the world. He had written Lock Up Your Daughters, Blitz, Maggie May and biggest of them all, Oliver!, which ran in the West End and on Broadway for years. He seemed to have the Midas touch and was now a millionaire living a millionaire’s lifestyle. A new musical written by Lionel and directed by Joan Littlewood seemingly couldn’t fail. The show was about Robin Hood and his Merry Men and was called Twang!:

The very next morning I regretted it. I found I was under contract to one or two good songs and no script, not even the outline of one.

The whole project was fatally misconceived from the start as a Ziegfeld Follies-style production with thirty showgirls, a full orchestra and baroque settings by Oliver Messel, who was supposed to be good at forests. Joan put together a company of old Workshop ‘nuts’ including Barbara Windsor and James Booth, and on the first day of rehearsals abandoned what little script there was and started improvising. War broke out between the creative team, and soon Bart was rehearsing one show while Joan worked on another, and Paddy Stone choreographed a third. Sgt Bilko writer Harvey Orkin sat in the stalls desperately thinking up new gags which Joan instantly dismissed. The script, costumes and casting were changed by the hour. Howard Goorney, playing Guy of Gisburn, famously went for a piss in one rehearsal only to find on his return that he was no longer in the scene. ‘Christ, Joan,’ he said, ‘it’s a good job I didn’t go for a shit or I’d be out of a job.’

Tensions worsened when Joan accused Lionel of being out of his skull on acid. She walked around with a script folder on which she had written ‘Lionel’s Final Fuck-Up’. There were rumours of a gangland stand-off between the Twins who backed Joan and the Soho villains who backed Lionel. The production opened in Manchester and in chaos. Unable to make it work, Joan walked and took her name off the poster. The producers brought in Burt Shevelove, a Broadway play doctor, to fix the show. He didn’t. Twang! eventually opened at the Shaftesbury and ran for less than a month. Bart had sold the rights of Oliver! to finance the fiasco. He lost a fortune.

The Fun Palace was finally killed off when Newham Council decided it needed the proposed site for a sewage pumping station which remains unbuilt to this day.

In 1967 Joan was back at Stratford East.

East 15 Acting School is not at Stratford East. It’s not in East 15 at all. It is based in Debden in Essex in a Georgian house called Hatfields.

Workshop member Margaret Bury founded the School in 1961 in order to pass on Joan’s principles and techniques to a new generation. Joan had disappeared to Nigeria, and the company had no idea when or if she was going to return.

Maggie Bury (or Margaret Greenwood at the time) had joined the company in the late 1940s after attending a summer school. She toured with them throughout Britain and Europe playing a variety of parts including Lysistrata, and in 1948 married actor/designer/director John Bury. When the company moved into the Theatre Royal Maggie and John lived in the prop store while Joan and Gerry lived in the top dressing room. The School was originally based in the Mansfield House Settlement in the East End but was now housed in a spacious but freezing mansion with a newly opened theatre. Converted by the students from a medieval tithe barn, the Corbett Theatre was named after benefactor Harry H. Corbett (rather than Sooty’s tiresome manipulator). Maggie lived in an apartment on the premises and strode the grounds in a leather trench coat and thigh-length boots, accompanied by two smelly dogs, looking every inch a sadistic KGB Commissar from a Bond movie.

I arrived at the School aged barely nineteen, shy, terrified and with no idea about what to expect or what I was doing there. It very soon became apparent that what I wasn’t doing there was a Directors’ Course. This was because there wasn’t one. There was another directing student called Matthew Higham, and the idea seemed to be that we would do the first-year Acting Course as well as absorbing directing wisdom by stage-managing the third-year shows and then play it by ear.

My fellow lively minded, argumentative, inventive, exquisite, vulgar, idealistic, talented students who wanted a livelier theatre, were a mixed bunch. Maggie clearly shared Joan’s proclivity for actors with diverse and colourful backgrounds. There was Tony Shear, an ex-morphine addict who had just got out of jail in the States for kiting cheques. There was Alan Ford, a market trader, stand-up comic, pub-singer and all round cockney geezer. There was a pastry cook from Scarborough, a captain from the Israeli Army, a toff from Eton, a lapsed member of the Provisional IRA and a woman from Canada with a spastic monkey. There were several students for whom English was not even close to being their second language. There were some forty of us altogether.

In the year above were Annabel Scase, whose parents David and Rosalie were founder members of Theatre Workshop; David Casey, who was the grandson of the great Jimmy James and son of James Casey who wrote The Clitheroe Kid; Oliver Tobias who went on to be, er… The Stud; and Alison Steadman, who even then was head and shoulders ahead of the rest.

The course consisted of classes in Acting, Speech, Laban Movement, Commedia dell’Arte, Singing, Fencing and Dramaturgy. Acting tuition was based on Stanslavsky’s An Actor Prepares and was built around a variety of improvisation exercises.

So much of this stuff has now become the common currency of an actor’s training that it’s important to emphasise how revolutionary it was seen to be at the time and with what suspicion it was regarded. Despite An Actor Prepares having first been published in 1937, Stanislavsky was a closed book to most English theatre practitioners and his work was often pejoratively and purposely confused with The Method and Strasberg’s Actors Studio, which involved Americans and mumbling. Bill Gaskill and Keith Johnstone at the Royal Court, Peter Brook, and Joan had been using improvisation techniques for years, but the majority of English actors, directors and drama schools distrusted the practice, despite having no real idea what it entailed. It’s also true to say that a majority of actors believed that theatre shouldn’t dabble in politics or discuss social issues. For the first half of the twentieth century British theatre was unassailably a middle-class activity. The plays were middle class, representing middle-class values to middle-class audiences, and as most of the roles available were middle class so were the actors. It was almost impossible to find an actor with a regional accent even to play the comical maid. There were times when even the best drama schools were regarded as little more than finishing schools offering training in elocution and deportment. Regional theatres staged either weekly or fortnightly Rep with actors rehearsing in the day and performing at night plus matinees. There was barely enough time to learn the lines and block the play, and there was certainly no time for experimentation or subtext analysis. This produced a rigidity in thought and an unwillingness to countenance change. Actors did not think it necessary or important to work on their craft, and any suggestion that they should would have been met with derision.

Unfortunately English actors were widely considered to be the best in the world, and equally unfortunately they believed their own publicity. Thus Improvisation, Units and Objectives, Laban Efforts and Character Research were clearly unnecessary and possibly dangerous. The idea that theatre should have any purpose other than entertainment was probably subversive. The ridiculous regime of the Lord Chamberlain ensured that theatre could never seriously discuss sex, religion, politics, the royal family or homosexuality, or engage with topics even remotely socially relevant; since all scripts had to be approved several months in advance of production by a coterie of retired army officers, creating dialogue through improvisation was theoretically illegal.

By 1967, however, the Establishment in theatre and everywhere else was starting to crumble.

Our first-year acting tutors were Robert Walker and Richard Wherret, both ex-students, and they cheerfully announced that their job was to break us down. There was no mention of putting us back together again. Their aim was to make us lose our inhibitions, to become unafraid of making fools of ourselves and to learn once again to play as children.

Each day began with a warm-up. This usually started with a physical stretch and shake-out session and then progressed into games. These could include kids’ party games like Grandmother’s Footsteps, Hide and Seek, British Bulldog or Blind Man’s Buff. There were ornate sophistications. A Rob Walker warm-up would often start like this:

ROBERT. Right, Timothy, I want you to go into the bogs and toss yourself off. Go on, don’t be a cunt, just go and do it.

ExitTIMOTHY.

Right, Cordelia, I want you to go and watch him.

ExitCORDELIAin tears.

Everybody else, we’re playing tig. Last one to touch Jane’s tits is ‘it’!

Further inhibition-busting exercises included The Wanking Donkey, in which you had to pretend to be a wanking donkey, and Making Love to a Chair, which was equally self-explanatory.

Improvisation classes were mainly devoted to what have now come to be known as Theatre Games or Theatre Sports. These took many forms, but the emphasis was on spontaneity and preferably comic invention. A basic exercise would involve everybody sitting in a circle. One person mimes an object and then passes it on to the next person, who changes it into something else, thus an umbrella becomes a telescope and then a banana or a hand grenade. In another version of this an actor creates a physical sequence of movement, which is copied and mutated by the next actor. So climbing a ladder becomes digging a hole. A game similar to Statues involved everyone contorting themselves into grotesque positions and a chosen actor then describing them as exhibits in a museum. This gave everyone ample opportunity to comment on the physical peculiarities of their fellow students. There was an exercise that involved everybody swapping clothes and impersonating each other and several that involved groping about in the dark. Some involved snogging. There were Trust Exercises where you jumped off a table and the others caught you. There were Status Exercises involving servant-and-master domination games. There were exercises in instant characterisation along the lines of ‘You’re a vicar and you meet Marilyn Monroe and a tramp at a kosher deli.’ The purpose of this kind of improvisation is for the actor to adapt to the circumstances and come up with instant dialogue. As an exploration of real character or motivation it’s a complete non-starter. Alongside all this frenzied spontaneous activity we were also studying An Actor Prepares.

Stanislavsky concerned himself with truth in acting as opposed to the mechanical representation and demonstration practised in most European theatre at the time. He placed great emphasis on the power of imagination and the importance of Emotion Memory—how an actor conjures up parallel emotions from his own life to those experienced by the character he is playing. Accordingly we spent many hours sitting in a circle trying to conjure up traumatic episodes from our childhood that might come in handy. Everyone seemed to have a tragic tale to tell. Even the Old Etonian had been expelled for consorting with domestic staff. We learnt about Concentration and Observation, The Unbroken Line, The Inner State, and Units and Objectives.

Working on a text an actor breaks down each scene into sections—units of action that chart the journey of the character. The actor then decides what is the character’s objective in each unit—that which the character seeks actively to achieve. What the character wants. There are different objectives for each unit and a super-objective for the entire play. We spent many hours deconstructing texts and breaking them down into units and objectives.

Workshop actor Dudley Sutton recently told me of Joan Littlewood’s take on the subject:

I reckon the most important thing about Joan—and what differentiated her from the Royal Court—was that the objectives we sought always had to be non-intellectual, physical and forward-moving—she reckoned (and I seem to remember this from rehearsals for The Dutch Courtesan) that there were only four real questions: Who’s got the food?, Who’s got the power?, Who’s got the money?, Who’s got the sex? With these clearly in mind, she reckoned, you could walk into any play, well armed against bullshit directors.

During the rehearsals for The Quare Fellow, Joan had devised a series of improvisations in which the actors spent weeks living the life of prisoners in Mountjoy Gaol. They used the roof of the theatre as an exercise yard, marching round and round, and being drilled by the screws. They improvised slopping out, cleaning the cells and the day-to-day sheer boredom of the prison existence. Only after the circumstances and relationships had been fully explored did Joan introduce the text. East 15 had its own version of this that invariably involved being peasants.

Taking as the starting point The Weavers by Gerhart Hauptmann, Lope de Vega’s Fuente Ovejuna, or any play involving a downtrodden mob, the students would create meagre hovels in the school grounds and live in them in character, unrelieved poverty and deepest misery. Everyone wore peasant clothing and lived on peasant food cooked on peasant fires, usually in winter, while imagining what it felt like to be oppressed. In later years this extreme form of improvisation became an East 15 trademark, and students spent weeks living on acorns and road kill and scavenging in the dustbins of Loughton as they recreated life in a Stalinist gulag or the Somme. Eventually Health and Safety kicked in when students started to go down with dengue fever, trench foot and dhobi’s itch.

An Actor Prepares takes the form of a fictional account of a young actor, Kostya, learning acting at some late-nineteenth-century Russian conservatoire or drama school: ‘Today the Director asked us to repeat the exercise in which we searched for Maria’s lost purse.’ An East 15 Actor Prepares would more likely be: ‘Today the Director asked us to repeat the exercise in which Lavinia performed The Wanking Donkey.’

Jean Newlove taught Laban Movement in what had once been a Scout hut in what had once been an orchard in the grounds of the School. A trained dancer who had worked with the Kurt Jooss ballet, Jean had assisted Rudolf Laban at Dartington Hall during the war and helped him to set up The Art of Movement studio in Manchester. After introducing Laban techniques to the Theatre Workshop company at their summer school she joined the company at the same time as Maggie. She acted with the company for many years and was their movement teacher and choreographer for The Hostage and Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be. She had been married to Ewan MacColl and they had two children, Hamish and Kirsty. Kirsty MacColl became a successful recording artist who was tragically killed in a boating accident. Joan was their godmother.

Rudolf Laban was an Austro-Hungarian dancer, choreographer and movement theoretician. He was the founder of the Free Dance movement and created pacifist and political ballets. He was appointed to choreograph the opening ceremony for the 1936 Berlin Olympics but fell foul of Goebbels who banned the performance after seeing a dress rehearsal. Laban escaped to Britain in 1938. He invented a new language and theory of movement, and it fell to Jean to pass it on to us. It was not the easiest of tasks. Although some of the first year had had some dance training (and in some cases military training), most of us were terribly unfit and almost all of us were smokers. For several weeks we coughed and wheezed our way through a series of stretching and spatial awareness exercises. We worked on balance and extending our range of movement, we worked on different rhythms like skipping, running, hopping and jumping, and then we did it backwards. In pairs we improvised imaginary sword fights and games of tennis, and in groups we wrapped ourselves into bizarre structures and created weird human machines by crawling over each other’s bodies. Some of it was painful. Quite a lot of it was sexy. After all, Laban had been influenced by Freud. After a few weeks we had not unsurprisingly lost all our physical inhibitions. Then we had to make a model of an icosohedron.

An icosohedron is a twenty-sided crystal-like structure with which you can illustrate the possible planes of movement around the body. First we made small-scale models out of sticks and glue. It was like a class Blue Peter