Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

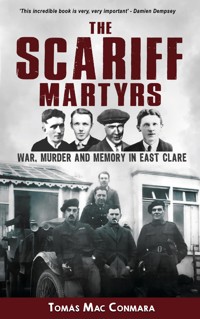

'This incredible book is very, very important'. Damien Dempsey In November 2008, Tomás Mac Conmara sat with a 105 five-year-old woman at a nursing home in Clare. While gently moving through her memories, he asked the east Clare native; 'Do you remember the time that four lads were killed on the Bridge of Killaloe?'. Almost immediately, the woman's countenance changed to deep outward sadness. Her recollection took him back to 17th November 1920, when news of the brutal death of four men, who became known as the Scariff Martyrs, was revealed to the local community. Late the previous night, on the bridge of Killaloe they were shot by British Forces, who claimed they had attempted to escape. Locals insisted they were murdered. A story remembered for 100 years is now fully told. This incident presents a remarkable confluence of dimensions. The young rebels committed to a cause. Their betrayal by a spy, their torture and evident refusal to betray comrades, the loneliness and liminal nature of their site of death on a bridge. The withholding of their dead bodies and their collective burial. All these dimensions bequeath a moment which carries an enduring quality that has reverberated across the generations and continues to strike a deep chord within the local landscape of memory in East Clare and beyond.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The following letters underline powerfully, the profound tragedy and sadness at the heart of the Scariff Martyrs’ story. The first letter was written by Alphie Rodgers when he was a fourteen-year-old boy in Mungret College, Limerick. The second was written just days after his murder in November 1920. Both illuminate the essentially human experience buried in the history.

Mungret College, Limerick – 23 January 1912

Dear Mother,

Hope you are well. I received your parcel the other morning. The cake was grand and also the nuts and sweets. I am getting on grand here now and am as ‘fat’ as a little puppy dog. We had high mass here on last Thursday. Every morning at mass, I do say the five rounds of the beads for yourself and pop and then another round for myself and the children and sometimes I offer up my communion for ye. I know you will be glad to hear that. I am very fond of praying since I came here and all the lads call me a saint but I don’t pay any heed to them as I think I am doing good … I am enclosing a letter in this envelope for Gertie. Don’t forget to give it to her. Them were grand beads she sent me.

P.S. Don’t forget to tell Antie [sic] that I sent my best love to her.

Love to all fromAlphie x

St Louis’ Convent, Kiltimagh, Mayo–19 November 1920

He is now D.V. [God Willing] enjoying peace after all his trials of the last few months. Another martyr, in the long list of those who have given their all in the cause of our country. We little thought, when we saw him in April, with his splendid life opening up before him, what a terrible tragedy was coming … we were talking today of the wild Alphie of long ago, with the little black and red skull cap, who used to tear around on the bicycle and of the splendid boy who was up here only three years ago. He was such a good proud boy in spite of all his pranks and that time he produced his beads for us and told us he was Our Lady’s Pet, as he was born on her feast day. No doubt she has been guarding him all the time and now she has him safe at last, where no worries can trouble him again.

Your loving cousin,

Baby McDermott*

* Rodgers Collection, Alphie Rodgers to Mrs Nora Rodgers, 22 February 1912; Baby McDermott to Mrs Norah Rodgers, 19 November 1920. 11 February is the Feast day of Our Lady of Lourdes in the Catholic calendar. Alphie was born on 11 February 1893. ‘Gertie’ referred to inAlphie’s letter was his younger sister, who was ten at the time.

Tomás Mac Conmarais an oral historian and author from Tuamgraney, County Clare. He was awarded a PhD at the University of Limerick in 2015, for his study into the memory of the Irish revolutionary period. He began recording older people in his townland of Ballymalone as a teenager and is now recognised as one of the leading oral historians in Ireland. He has written several books includingDays of Hunger, The Clare Volunteers and the Mountjoy Hunger Strike of 1917, The Ministry of Healing, Cork’s Orthopaedic Hospitaland the best-selling,The Time of the Tans.

DEDICATION

To Dan McNamara (1932–2019), my father.

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Tomás Mac Conmara, 2021

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 726 6

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Printed and bound in the EU.

Acknowledgements

Before I knew the history of the Scariff Martyrs, I knew the feeling of it. It was there, embedded in the way people spoke. Writing in 2021, after many years immersed in the story, I feel I have drawn closer to an understanding of that experience. My own philosophy of history does not simply surround the accumulation of knowledge about the past, but the cultivation of understanding. To this end, I have listened. To make such a pilgrimage to the innermost districts of our past, one must attend to the role of place, people, and memory in our historical consciousness. With this, I believe, comes a greater knowing; one that can illuminate the hidden contours of our historical experience and enable us, in our time, to inhabit a much richer landscape. For all this, I owe gratitude to many – firstly, to Mary Feehan at Mercier Press. Special thanks to the Rodgers family, in particular Mike and the late Paddy Rodgers, for their support over many years. Also, to the relations of Martin Gildea, especially his niece Kathleen Mitchell and of Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon and Michael Egan, my thanks for allowing me into your family memory. To the interviewees who contributed memories and tradition, I owe heartfelt appreciation. A singular thanks to my friend, Cllr Pat Hayes as well as May Ryan, Shane Walsh, and the late Dermot Moran of the East Clare Memorial Committee. Thank you to Prof. Bernadette Whelan (UL), Comdt Daniel Ayiotis, Noelle Grothier and Cecile Gordon (Military Archives of Ireland), Helen Walsh and Peter Beirne (Clare Library), Dr Críostóír Mac Cárthaigh in UCD and Dr Cliona O’Carroll, UCC. To the wonderful historian Tom Toomey for his valued guidance and to fellow historians, Liz Gillis, Lar Joye, Colum Cronin, David Grant, Ernest McCall, Paul Minihan, Daniel McCarthy, Dr David Fleming, Meda Ryan, Prof. Eunan O’Halpin, Jackie McCarthy Elger, Dr Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc, Dr Eve Morrison and John S. Kelly, my respect. My gratitude to historian Ger Browne for his incredible work and generosity with RIC records in Clare and to Kevin Welch in New Zealand for restoring photos. My friendship to Frances Madigan, Jack McCormack, Moira Talty, Comdt Stephan Mac Eoin, Ciarán and Joanne Maynes, Danny Morrison, John Moroney, Colm Scullion, Tomás Madigan, Carol Gleeson, Gerry O’Grady, Peter and Brian Flannery, Clive Kelleher, Kieran Brennan, PJ Kelleher, Seán McNamara, Matt Kelly and Marian Malone, Harry Duggan, Noeleen Moran, Paula Carroll, Shane O’Doherty, Brendan McMahon, Kevin Cullinan, Laura O’Brien, Michael and Marian Conroy, Teasie McCormack, Gordon Daly, Helen and Christy Venner, Derek and Elaine Venner King, Siobhán Reddy, Joe Fitzgerald and Darren Higgins. To Michael O’Gorman, Frank Mason, Patricia Sheehan, Gerry and Brian Quinn, Sarah Geraghty, Fintan McMahon, John Fahey, Carol McNamara, Una Kierse, Margaret O’Meara, John Joe Conwell, Joe Duane and the late Maeve Hayes for support and access to collections. A special word of thanks to my great friend Jimmy Walsh from over the fields in Caherhurley and to Tommy Holland, Whitegate, who have both given me constant support for many years and have remained loyal to the Scariff Martyrs since first they heard their story against the open hearths of their homes.

Thank you to my mother Annamae McNamara, whose uncle sang about the Scariff Martyrs and to my sisters Myra and Bríd and my brother Dónal. To Dara for her insightful and wise counsel on the book’s more subtle expressions and for being the reassuring dawn of every day. Finally, to Dallán Camilo and Seód Nell Áine; clamber again and again, into that whirlwind.

Tomás Mac Conmara – May 2021

‘I Cried after Them’

Prologue

A gentle, almost subconscious nudge of the turf led to a clash of fire that burst an intense moment of warmth. Forty- three-year-old Bridget Minogue quietly watched the embers of her old open hearth as she had done a thousand times before, locked in the ancient conversation between mankind and fire. The scent of turf smoke that escaped the chimney’s draw wafted gently around the farmhouse as it had done for decades. Tradition and continuity were at home. Bridget was taking a brief moment of rest from the long, duty filled day of a rural housewife and mother.

The winter of 1920 had taken a firm hold of the east Clare landscape and the Minogues of Poulagower in Scariff were ready for the long dark nights ahead. It was November and cold. Although early in the evening, the light had already given way to the dark. Just feet away, her daughter, Margaret, allowed the warmth of the turf-fuelled glow to reach her cheek, before shaking away her distraction and returning to her duties. As Bridget pushed her hands against her knees to make her body rise, her mind drifted to the many faces that were warmed by the flames in the past. She recalled the old men who came ‘on cuaird’ (visit). She remembered the men quietly sitting, deferential to a storyteller, a craftsman weaving his tale for attentive listeners. Such scenes were rare of late. A strange vulnerability had ripped the community of its comfort and left a tension weighing heavily on its people.

Bridget had just stood and was slowly moving from the hearth when she was jolted by a loud bang on the door of her home. Sixteen-year-old Margaret’s eyes widened as she drew a sudden intake of breath. After casting a momentary glance at each other, Bridget moved cautiously towards the door. The lack of a second knock or shouts from outside was somewhat reassuring. Nevertheless, the latch was lifted with trepidation. The opening door revealed a young man who stood casting a countenance lost somewhere between panic and fear. Margaret stood closer to the open hearth, her eyes fixed on the young man she did not know. She saw her mother’s hand move to her mouth as the man spoke. She could make out the words ‘Killaloe’, ‘murdered’ ‘all dead’. Instinctively moving closer, she heard names she knew, ‘Alphie Rodgers, ‘Brud’ McMahon and ‘Gildea who worked in Sparlings.’ Another name was mentioned but by then her mind had rejected all noise and was focused internally: ‘Not Alphie,’ she thought, ‘Not Brud’.

In November 2008, I sat with a 105-year-old woman at a nursing home in Newmarket-on-Fergus, Co. Clare. While gently moving through her memories, I asked a question that had been impatiently waiting on my mind: ‘Do you remember the time the four lads were killed on the Bridge of Killaloe?’ I knew Margaret Hoey was a native of Scariff and hoped she had some sense of the event, perhaps even remembered it.

Almost immediately, Margaret’s countenance changed to one of outward sadness, her old shoulders dropping as if some heaviness had taken hold of both her mind and limbs. Before responding, Margaret’s eyes already betrayed some long-held distillation of understanding. She began to take me back to 17 November 1920, when she was sixteen-year-old Margaret Minogue and when the story of the four men’s brutal death was revealed to the community. Margaret had left her native place over eighty years before I recorded her memories, yet it quickly became apparent that her native place had never left her.

There are occasions when a disclosure of memory can be so powerful, so wrought with emotion, that for a brief moment you find yourself transported on a journey of recollection. So it was in Carrigoran Nursing Home when Margaret Hoey, born five years and a century earlier in 1904, revealed to me a moment marked indelibly on her memory. For a time, I felt as if I was there standing near the open-hearth fire of her home when her mother opened the door to a frantic IRA Volunteer. Four young local men had been killed. Margaret knew three of them. Within the fold of her memory, I walked and then ran with Margaret as she quickened her pace up the avenue adjacent to her home. She had been dispatched there to warn other IRA Volunteers who were ‘on the run’ and sheltered in a local safe house. Back then in 1920, she had cried as she ran. As I listened eighty-eight years later, she cried as she spoke.

I stood beside her as she knocked shyly on the door. I was there when the man of the house shouted at her, frustrated at her failure to speak words through her tears. It was the anxiety of a man who wanted to know but feared the knowledge. I saw his face change as those devastating words broke through Margaret’s quivering voice:

I was of course, I was crying like a child. Anyone would be upset. ’Twas a terrible thing. To say they were brought out and shot on the bridge in Killaloe, between Tipperary and Clare, between Ballina and Killaloe. Oh, ’twas a terrible thing! I did, I cried after them … the lads were all joined the Volunteers. There was a safe house, along an avenue in from us. One Volunteer, I didn’t know who he was, came to the house and he said to my mother, ‘could anybody give a message?’ in the way there was lads ‘on the run’ in a house in the avenue. ‘Oh’, she said, ‘Margaret can do that easily’ and I was dispatched off in the avenue. And shur naturally, I was crying for I knew ’em. And when I went into the house where there was a couple of [IRA] lads asleep. I was crying and the man in the house let a shout at me, ‘what’s wrong with you?’ And ah, [begins to cry] I told ’em. ’Twas bad news.

With this simple but profoundly emotional disclosure, I became intensely aware of how forcefully the memories of the four men, who later became known as the Scariff Martyrs, had been imprinted on local memory.

Margaret Hoey died just weeks after that interview. The emotion of Margaret’s disclosure is a clue to the impact of the incident on the local community and can only begin to indicate the deep trauma suffered by the families affected. The story of the Scariff Martyrs is one of both history and memory. Why such a brutal and traumatic event became an enduringly remembered landmark in local history, and how so much pride and reverence has been embedded in the historical consciousness for the four victims, helps illuminate the Irish historical experience and the role of memory. From its foundation, there was duality of experience. On one hand, there was martyrdom and the pride of a community connected to such a site and moment of memory; on the other hand, there was the deep and enduring pain caused to the families involved. The families of Alphie Rodgers, Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon, Martin Gildea and Michael Egan did not want martyrs. All of the families regretted hugely the incident and likely lamented their sons’ involvement with the IRA. This does not equate to a rejection of the cause for which they fought, nor does it betray a lack of pride in the story. It simply points to the primarily human impact of the story on those affected.

For the Egans, the blow struck deeper, perhaps, as the incident saw their son pulled into a vortex of violence that he had no role in creating. The story presents a remarkable confluence of dimensions: the young rebels committed to a cause, their betrayal by a spy, the virtue of Egan, their torture, their evident refusal to betray their comrades, the loneliness of their end, the liminal nature of their site of death on a bridge, the withholding of their dead bodies and their collective burial. All these dimensions, when combined, bequeath a moment of memory, which carries an enduring quality that has reverberated across the generations and continues to strike a deep chord within the local landscape of memory in east Clare and beyond.

Introduction

Sometime between 11.30 p.m. and 12.30 a.m. on the night of 16 November 1920, on the bridge connecting Killaloe in south- east Clare to Ballina in north Tipperary, four young men were shot dead by British crown forces, having been arrested earlier that day in the north-east Clare parish of Whitegate.1 Three of the men, Martin Gildea, Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon and Alphie Rodgers, had been active members of the Scariff Company in the 4th Battalion of the East Clare IRA. The fourth, Michael Egan, was a civilian who was the caretaker of Williamstown House in Whitegate, where the other three had been sheltering while ‘on the run’. British authorities reported that the men had been shot while attempting to escape. That was immediately countered by local claims that the men had been murdered in cold blood.

In social memory, the victims are referred to interchangeably as ‘The Scariff Martyrs’, ‘The Killaloe Martyrs’ and ‘The Four Who Fell’, depending largely on where the reference is made. The story endures as a landmark on the historical landscape and consciousness of east Clare with multiple commemorations, sites of memory and songs. Because of the way the story unfolded, three areas of east Clare inherited an enduring relationship with the incident: Whitegate, where the men were captured; Killaloe, where they met their deaths, and Scariff, where three of the men worked and where they were collectively buried on Saturday, 20 November 1920.

Until the Glenwood ambush in January 1921, where six members of a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)/Black and Tan patrol were killed by the East Clare IRA, the incident in Killaloe had been the most significant event of the Irish War of Independence within the brigade area. It represented the single biggest military blow to the Clare IRA during the entire war, with three of its active members killed at one time.

The incident took place during arguably one of the most crucial months of the entire War of Independence. The president of Dáil Éireann, Éamon de Valera was close to the end of an intensive tour of America, where he was attempting to secure recognition of the Irish republic. Three weeks earlier, on 26 October 1920, Lord Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney died after seventy-four days on hunger strike in Brixton prison in England. Ten days after the Killaloe bridge incident, members of D Company of the Auxiliaries, highly trained ex-officers sent in to further bolster the RIC and Black and Tans, murdered republicans Harry and Pat Loughnane with astonishing brutality in Galway. Two days later, seventeen Auxiliaries attached to their colleagues in C Company in Macroom, were killed in the Kilmichael ambush on 28 November, led by Tom Barry of the 3rd West Cork IRA Brigade. That four-week period included the hanging of eighteen-year-old Kevin Barry, the elimination of the ‘Cairo Gang’, a British intelligence network by Michael Collins’ ‘squad’ and Bloody Sunday. In the same month a twenty-four-year-old-pregnant woman, Eileen Quinn, was shot through the stomach by British forces as she sat outside her home in Kiltartan, Co. Galway and died eight hours later, by which time a cover up had already begun. In just seven days from 20 to 27 November 1920, British forces in Ireland killed at least thirty Irish men, women and children, including four under the age of fourteen. In the same month, fifty-seven members of the British forces were killed by republicans, including British army, intelligence servicemen and members of the RIC. With a whirlwind of violence sweeping the country, the story of the Scariff Martyrs began to fade from the national discourse and was perhaps from that moment the preserve of the local.

During the revolutionary period, the four young men, forever bound together in history, lived in the same area. Rodgers, McMahon and Gildea worked in the same small town, where they were employed in the principle stores in Scariff, two of whom (McMahon and Rodgers) were the sons of those business owners. Michael Egan had lived in Tuamgraney for a period and was a frequent visitor to Scariff town where he worked as a part-time postman.

Egan was born in Rinskea in Co. Galway on 26 October 1897 (the townland became a part of Clare a year later) to farm labourer and herdsman, Daniel Egan and his wife, Mary. At the time of his death, he had only recently turned twenty-three and was the youngest of the four men. He was the oldest son of the Egan family and was one of ten siblings, with only his sister Bridget being two years his senior. Decades after his death, his neighbour Mary Joe Holland cried when describing to her daughters how Egan was ‘as innocent as the flowers of May and was a really lovely innocent young man and fierce gentle and nice, always smiling and always had a kind word’. In the autumn of 1920 at a house dance held in Drewsborough, Tuamgraney, nineteen year old Mary Hill from the townland of Ballymalone, my grandmother, danced with Michael, telling her son many years later about the shy and gentle countenance of the young man she was one of the last to dance with before his death.15 Even the press at the time characterised Michael as a ‘most inoffensive young man’.16Egan was not a member of the IRA. He was tragically pulled into the story by his decision to allow Rodgers, McMahon and Gildea to stay in the house where he was caretaker and his attempts to divert crown forces when they came to Williamstown looking for the men.

Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon was born on 12 April 1893, to Thomas and Bridget McMahon. He was the second eldest of four sons born to the couple who ran a hardware and grocery business in the town of Scariff. Having attended Scariff National School, Michael was sent with his brothers to Cork City for secondary education. At the age of eighteen, he was living in Cork City, while attending school with his brother, Patrick. His older brother, Denis, was working at Robert Scott and Co. Ltd, a large Hardware Merchants on St Patrick’s Quay.17 The three brothers lodged with Margaret Carbery in Sheare’s Street. Margaret previously lived in Scariff, where her husband, RIC Constable John Carbery was based and where he died of pleurisy in 1898.18 Evidently, a relationship was maintained between the McMahons and the RIC man’s widow, a union of gentler times. In the revolutionary period, Michael seems to have taken a leading role in the cultural revival and was recognised as ‘a member of the Fáinne’ (Irish-speaking) and ‘one of the principle people involved in the attempt to revive the Irish language in east Clare’.19 He was also well known in Carrigaholt and Ring Irish colleges and frequently contributed articles to the press, advocating the promotion of Irish.20 Described as ‘very sincere’, ‘Brud’ was a senior figure in the Scariff IRA Company at the time of his death.

In 2012, 100-year-old Matthew Birmingham told me that Mollie Behan, owner of the Burton Arms Hotel in Carrigaholt, had fallen for McMahon while he was staying there while attending the local Irish College. According to Birmingham, Behan, who in 1916 had sheltered local leaders during the Easter rebellion, never married because she ‘had a particular standard’ and ‘could not find anyone to match McMahon and so would not settle for anyone else in her life’.21 A family rumour indicated that McMahon was also romantically linked to Lillie Corbett, who in 1920 was a twenty-four year old from Scariff who shared McMahon’s interest in the Irish language. Lillie later moved to France where she joined the French Sisters of Charity.22

Martin Gildea has been reported as being aged interchangeably as twenty-four and twenty-seven.23 In fact, Gildea was born on 16 May, 1890 at Ashbrook, Woodlawn, in the parish of New Inn, Co. Galway, making him thirty years old at the time of his death, the oldest of the four and at a senior age for an IRA Volunteer.24 Martin was born to Michael Gildea and Nora Kelly, who both worked at the estate of James Ryan, owner of Ashbrook House. After both her father and Ryan disapproved of her intention to marry Michael, Nora secretly followed Gildea to America, where they married and began a family.25 Having returned years later due to Nora’s ill health, Michael resumed his employment as a coachman for Ryan and moved his family into a house on Ashbrook estate.26 There, Martin was born soon after their return. Tragically, Nora Gildea passed away in April 1899 at the young age of thirty-eight from phthisis, a progressive wasting disease, worsened by giving birth three months earlier.27 Her register of death shows that her daughter and Martin’s baby sister, Honoria, died just eleven days earlier. Martin was then only eight years of age.28 As young man, he worked in Fahys Grocery Store in Loughrea, before later moving to Kilcullen in Co. Kildare, where he was employed as a shop assistant for businessman, Laurence Darby.29 In approximately 1916, he moved to Scariff, where he began working for Denham Sparling, a merchant in the town and soon after that he joined the Irish Volunteers. Gildea had a strong interest in Irish dancing and taught it locally, which according to one interviewee endeared him to many in the community.30 Like McMahon and Rodgers, Martin Gildea too left a young love at the time of his death. Twenty-one-year-old Sarah ‘Lil’ Fogarty from Lakyle in Whitegate was reportedly so distressed at the funeral that she had to be carried out of the church.31Lil never forgot her first love, choosing to remain unmarried for the rest of her life.32

Alphie Rodgers was the youngest of the three IRA men who died on Killaloe Bridge and was only Egan’s senior by eight months, having been born on 11 February 1897. Alphie was the first child born to Edward and Norah Rodgers. He was remembered as ‘happy go lucky’, ‘full of fun’ and ‘a bit of a devil’ by those who knew him.33 His oldest sister later underlined Alphie’s generous nature, remembering; ‘we thought he would give away all we had!’34 Having attended Scariff National School for most of his youth, Alphie’s father decided to remove him when it was established that the assistant teacher ‘believed too much in the use of the birch’.35 The Irish Jesuit Archives in Dublin, show that on 1 September 1911, Alphie was admitted to Mungret College, a Jesuit boarding school in Limerick where he remained until the summer of 1914, when his school career was recorded as ‘very satisfactory’.36 In a remarkable and tragic coincidence, Alphie and two of his classmates at Mungret, Timothy Madigan and Christopher Lucey, were shot dead within a month of each other. Lucey was killed fighting in the Ballingeary Ambush on the same day that Alphie was buried in Scariff.37 Madigan was shot a month later, on 28 December, after he was captured by the RIC and Black and Tans in Shanagolden, Co. Tipperary.38 Amongst obituaries to the above, The Mungret Annual of 1921 reflected on Alphie as a ‘natural leader’ with a ‘compelling personality’.39 For a short time in Mungret, Alphie also had as his schoolmate a young Tom Barry from Cork, later to become one of Ireland’s most famous IRA leaders. According to one interviewee, before his time ‘on the run’, Alphie had been in a relationship with a twenty-three-year-old Irish speaker from Sixmilebridge called Lizzie Clandillon.40 Senior brigade staff, in the East Clare IRA, later recorded in relation to his IRA service that Alphie Rodgers ‘served under arms’ and ‘was never absent from duty up to the date he was shot dead’.41

His brother Gerald was included in the nominal list as a Volunteer in the East Clare IRA and his sisters Gertie and Kathleen were members of the local Cumann na mBan.42 At the time of her brother’s death, Kathleen (Keesha) was in a convent in Belgium as part of her training to become a nun with the La Sainte Union.43 She later wrote that while there she ‘received the terrible news that my brother Alphie was had been shot by the Black and Tans’ and lamented ‘this was a very heavy cross for me and my family’.44 It was not the custom for postulants to leave the convent and so Kathleen did not attend her brother’s funeral.45 In the weeks after his death, Kathleen, then Sr Agnes, was given special permission to change her religious name to Sr Alphonse Columba, in memory of her brother.46 On 27 November 1920, she wrote to her family in Scariff, poignantly expressing both her own grief and theirs:

What can I say to you? Words are useless – God alone and the Mother of Sorrows can talk to the hearts broken by an overwhelming and too timely grief. He will console you and waft across the waters my unutterable sympathy. Yes, and the dear white soul now in his heavenly home will send down roses on you … For I feel that the sacrifice he has so willingly made of his young and so beautiful life has secured for him the goal of all good Christians … O Mamma dear! You will miss your white-haired darling boy – your eldest born, your dearest and your best … I even pray to him that we may all die as gloriously as he. Let us look forward to the day when he will cross the Heavenly courts to wish us a real ‘Céad mile failte’ into the mansion of eternal bliss … they [fellow sisters] say I should be proud to have a martyr in Heaven.47

The three IRA men had been well known in the town of Scariff. Their former comrade Tommy Bolton, fondly remembered the men’s jovial nature when he was asked to describe them in a taped recording, made in 1989:

Oh indeed I do and I knew ’em well. I knew ’em as well as my right hand. I remember buying the first razor, open blade razor from ‘Brud’ McMahon and poor Gildea came in the same day and he said ‘Bolton, buy another of them, ’tis the time of the war they won’t be ever got again.’ Ah you know takin the lift of me you know!48

When, in 2008, I asked 105-year-old Margaret Hoey to recall the men, she easily created an image of them:

I knew Brud McMahon as well as I knew my brothers. Oh, Alphie Rodgers was as fine a fella as you every laid an eye on. Oh, a tall fine lookin young fella … He was six foot, a fine young man … dark haired. Oh he was fine fella! But Brud McMahon, he was known as Brud, Michael was his name … was a fine fella too … Martin Gildea was a nice type of lad too. Gildea was a Galway man. Of course he was one of the boys [IRA]. He was shop hand at Sparlings. I knew him to see from going into the shop … I didn’t know Egan.49

The importance of the Scariff Martyrs incident as a historical landmark is manifest in its reference in at least twelve local publications relating to east Clare.50 While no publication has to date, exclusively addressed the incident, both ‘A Salute to the Heroes of East Clare’, written by Mary Moroney and Graney’s ‘East Clare’s Calvary’ offer two significant contributions. The latter, published in 1953 in Vegilla Regis, an annual journal from Maynooth College, contains interviews conducted with contemporaries to the event, including John Conway, one of the two Conway brothers who were arrested at Williamstown with the four men.51 Conway testified to the beating of the four men and offered some crucial information which will be discussed later.52 Importantly, a pamphlet written shortly after the incident by Romer C. Grey, a retired British civil servant, living in Killaloe and published by the ‘Peace with Ireland Council’, offers an essential account. Grey condemned the combined British forces in his booklet TheAuxiliary Police and accused the Auxiliaries in Killaloe of ‘murder’.53 In Ireland Forever, Brigadier General F. P. Crozier also made some serious allegations against the Auxiliary Division, including those stationed in Killaloe.54

There are two predominant contested accounts about the event: an official explanation and a vernacular folk memory. The official version is encoded in reports from Dublin Castle, which ultimately stem from a military Court of Inquiry, held two days after the killings. There, the claim that the men were shot while trying to escape was asserted.55 The vernacular memory offers a radically different version, which suggests the men were tortured and murdered by the British forces.56

A determined and public effort to remember was obvious from the first anniversary of the incident in November 1921. In fact, the Scariff Martyrs, with three connected monuments, six compositions and a consistent commemorative history, is one of the most memorialised, commemorated and remembered events of the period in Clare and across the country. The in- clusion of the best-known song about the Scariff Martyrs, on a 1970s album by Christy Moore, drew national attention to the story.57

As always, however, the assessment of any memory is only fruitful if silence is attended to as a revealing dimension. A revelation of what is known and unknown, spoken and unspoken, privately remembered and publicly commemorated, assists a deeper understanding. For over seventeen years, I have researched the event, compiling multiple first-hand individual accounts, as well as the comprehensive collection and analysis of oral history and tradition associated with the affair.

Ultimately, I explore in this book how these four men were drawn together to form one of the most enduring stories in Clare’s War of Independence. For a story so interchangeably dependent on history and memory, it is important for the book to commence by exploring the way in which the incident has been memorialised over the last century and to illuminate how that memory has effected both knowledge and emotion of the broader story.

1

‘We should take off our hats’

Remembering the Scariff Martyrs

On 17 November 1921, a large crowd gradually emerged from St Flannan’s Roman Catholic church in Killaloe. The congregation, led by the clergy, slowly descended the steep hill leading towards the bridge of Killaloe. There, in deferential unison, a rosary was recited in Irish. After a hush fell on the assembled crowd, one man walked forward and with white paint made the sign of a cross on the north parapet of the bridge.1 Exactly a year earlier, Michael Daly, a twenty-four-year-old railway worker from Canal Bank, had crossed the bridge and noticed at that spot a sight that never left his memory:

I was going to work at 8.45 a.m. I could see blood from Danny Crowe’s gate as far as the point where the monument was later erected. There was brain matter with the blood. There was so much blood on the bridge that at first I thought a cow had been killed … I swept in all the blood with a sop of grass or hay to the side of the wall and I found a cap beside the wall with Brud McMahon’s name on it.2

In September 1922, Daly established a committee to raise funds for the erection of a monument at the site.3 Largely as a result of Daly’s efforts, the monument was erected just three years after the killings, making it one of the earliest republican monuments in the country.4 Costing £72, in November 1923 the ornate monument made by Matt Nihil, a republican stone cutter from Hill Road outside Killaloe town, was integrated into the ashlar limestone on the north parapet of bridge.5 As a small child, the late Jack Quigley from Killaloe was at the unveiling. At the age of ninety-two he told me:

I can remember being there with my mother when they were putting that monument on the bridge, ’Twas a big big do … I was very young anyway. We couldn’t get near it anyway. There was trains and all you know and a very big crowd and bands.6

Twelve months later, the county’s newspaper commented that the new monument had become a ‘centre of attraction’ in the town and recorded that ‘almost unceasingly visitors could be seen rapt in devout prayer’ at the site.7Michael Daly emigrated to New York in August 1923 before its installation.8 Having returned in the 1930s, he took responsibility to ensure that a commemorative wreath adorned the site each year.9

By 1938, the monument was clearly an established feature of remembrance and nineteen pupils from Tuamgraney National School recorded its presence and function as part of their contributions to the Irish Folklore Commission’s School’s Folklore Scheme. If the pupils in Tuamgraney needed any encouragement to write about the Scariff Martyrs, they would get it from their principal, Waterford native and Irish language revivalist, Pádraig Ó Cadhla. Ó Cadhla, who was appointed principal in Tuamgraney in 1919, had befriended Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon due to their shared interest in the Irish language. When his first child Brigid was born, he chose McMahon as her godfather. It was love of the Irish language that nurtured another friendship, which resulted in the choice of the godfather for his second daughter, Maura: Conor Clune. Sadly, both McMahon and Clune were murdered within days of each other in November 1920.10

In 1938, pupils wrote of the common practice and social expectation that when passing the monument on Killaloe Bridge, ‘we should take off our hats and say a few prayers for those poor innocent boys’.11 Thirteen-year-old Brigid MacMahon was assured that; ‘in hundreds of years when we are dead and gone some child who will be passing will ask the story of that stone’.12 Brigid was the niece of Michael ‘Brud’ McMahon. Twelve-year-old James G. Minogue also contributed to the scheme and similarly determined that ‘children in hundreds of years’ time will be inquiring about that stone’.13 Minogue, who became a Roman Catholic priest, passed away in 2018. Seventy-six years after making the above determination, he told me in a recording in Limerick that the memory of the Scariff Martyrs had lost none of its potency.14

Whatever the exact occurrence on the bridge of Killaloe on that November night in 1920, from the moment news broke, the bridge took on a great significance for the people of Killaloe and of east Clare generally. A bridge with a practical and social function has since the night of the tragedy performed a third critical role: that of a landmark of memory, what the French historian, Pierre Norra, called a Lieux de Memoire.

Censoring Memory

While frequent commemorations were held at the bridge of Killaloe, evidence of a shift away from state involvement in republican commemorations emerged in a Dáil Éireann debate on 4 February 1942. Daniel McMenamin, a Fine Gael TD, asked Minister Frank Aiken ‘if the Censor stopped the publication of a paragraph stating that a ceremony attended by members of the Local Defence force had been held about the 17th November last in memory of four men who had been shot on the bridge of Killaloe in 1920’.15 The minister replied in the affirmative but did not elaborate on the reason. While official records indicate that permission had not been granted for participation, it is probable that the censorship related to the government’s move against the IRA.16 Over 1,000 IRA Volunteers were then interned in the Curragh Camp (known to republicans as Tintown), arrested under the Emergency Powers Act, which allowed for internment and executions.17

Despite the attempted censorship of the Killaloe com- memoration in 1941, the Clare Champion carried a report on 22 November on a commemoration held on the bridge of Killaloe the previous week. The paper reveals that the commemoration, held to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Scariff Martyrs deaths, involved members of the Killaloe and Ballina Local Defence forces.18

The commemorations continued, regardless of censorship. On Easter Sunday 1949, a former IRA commandant of the East Clare Brigade stood on the bridge of Killaloe as he knew there was only one place to mark the occasion. Joe Clancy, a former British soldier and IRA commandant from Kilkishen was then living in Killaloe and although the large crowd around knew Clancy, their instinct was to move back as he fired three shots into the air. Clancy had just delivered an oration at the site of the monument on Killaloe bridge. Clancy had known the men and spoke to them in the days before their capture and deaths. On that day, the Irish Republic was declared.19

On the bridge that day was John Fahy, who recounted his memories to me in 2019:

In 1949, the same year that the Republic of Ireland was declared, I was on the bridge when Joe Clancy held a commemoration to the four men. I remember him well pulling out a gun and we all scattered. He fired three shots into the air in memory of the Martyrs.20

From the early 1970s, following the death of Mike Daly, another Killaloe native continued the tradition of laying a wreath at the monument on Killaloe Bridge. Maeve Hayes accepted this responsibility from Nellie Grimes who like Mike Daly before her had laid the wreath for many years. Maeve told me how she was once approached by Nellie in the 1960s and asked to ‘put a few flowers on the bridge on the 16th of November’. That request led to a fifty-year commitment that Maeve annually honoured, even arranging for a nail to be added to the monument in the 1980s to elevate the wreath from the ground, thereby ensuring it was more prominent and remained at the site for longer.21

‘A Suitable Memorial’ – Scariff Monument

In Scariff, where the men were buried, the emotional con- nection to the killing has remained very strong. On the first anniversary of the incident in Scariff in 1921, ‘a great demonstration’ was held attended by approximately 5,000 people, including 1,600 Volunteers.22 Among the priests in attendance at Scariff was Fr Murray who acted as a chanter. Six weeks before their deaths, Rodgers, McMahon and Gildea had taken shelter with Fr Murray on their return from an IRA action in O’Brien’s Bridge. Ironically, Fr John Greed, who while the men sheltered with Fr Murray, was on his way to attend to the men they had shot, was also in the choir at the service. At the conclusion of the mass, IRA members in attendance moved in unison and structure to the year-old gravesite. There, under the command of Michael Brennan, a volley was fired over the graves. There followed an address by Brennan, then O/C of the East Clare IRA Brigade.

The Black and Tans were gone by this point and yet Ireland’s troubles were not over. The following year, the second anniversary was also marked when requiem mass was celebrated at Scariff church in November 1922. The divisions that had been emerging in 1921 were more pronounced twelve months later, as East Clare members of the Irish Free State Army led the congregation.23

In early 1945, the East Clare Memorial Committee was formed with the primary objective ‘of erecting a suitable memorial’ at the gravesite.24 A meeting was held at 14 Parnell Square in Dublin in early March of that year and appeals for funds were made at a national and local level through the press.25 Later that year, a monument was erected over the graves of the four men in Scariff.26 Before its erection, four independent white crosses, carrying the names of the men, had marked the grave. There in Scariff in November 1945 was Martin Gildea’s fourteen-year-old niece, Kathleen, who had travelled with her father from New Inn in Galway:

My father brought myself and my sister to Scariff in 1945 for the twenty-fifth anniversary. I remember there was a big crowd there and we saw the grave … I don’t think it meant as much as it does now. I was too young then. There were shots somewhere because I was frightened. I thought it was the Tans! I had been hearing it so long about the Tans!27

On the monument erected in 1945, Rodgers, McMahon and Gildea are inscribed with the rank of captain, while Egan, who although not an IRA Volunteer, is described as a lieutenant.

In December of that year, the Clare Champion published the names and contributions of 827 people, including ten listed anonymously as ‘friends’, predominantly from within Co. Clare, who donated between two shillings and £5 towards the construction of the monument.28 Amongst the subscribers were An Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera and Col George O’Callaghan Westropp, whose father had been at the centre of evicting tenants during the infamous Bodyke Evictions of 1887.29

Commemoration continued and in November 1947 the Scariff Memorial Committee held a fundraising dance, which was ‘very well patronised’.30 Four years later, in March 1951, the Tuamgraney Village committee declared their intention to honour the contribution made by men and women of east Clare.31 The memorial, which features a Calvary scene, was given significant financial support from New York and was finally dedicated on 20 July 1952 and attended by a crowd of over 2,000 people.32 Two years later, the park was formerly dedicated as the ‘Republican Memorial Park’.33

In November 1970, it was revealed that a fiftieth anni- versary commemoration would be held in Scariff where the four martyrs were to ‘be honoured with all the dignity and pomp they deserve’.34 The Tulla Pipe band, followed by surviving members of the East Clare IRA Brigade and Cumann na mBan, led the parade. A ceremony was held in Killaloe also.35 Twenty-five years later, a large event was held to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary in Scariff chapel.36

From the 1970s onwards, the withdrawal of the state from overt commemorative displays, resulted in a reduction of commemorations in north East Clare. However, repub- lican groupings, including Sinn Féin, continued to hold commemorations at the Killaloe site during the period of ‘the Troubles’.37 In 1972, following the murder by the British Army of thirteen civilians in Derry on Bloody Sunday, hundreds marched to the memorial on the bridge of Killaloe in solidarity with the victims.38

In 1983, the East Clare Memorial Committee was re- formed. A member of that committee recalled how the group were frustrated in their efforts by the local Catholic parish priest who labelled them ‘subversives’.39 Since the 1980s, that committee has continued to annually commemorate the men, inviting people connected with the story to lay a wreath in their honour at the grave in Scariff each year, including from 2008 to 2012, when Paddy Gleeson and John Michael Tobin, the last two people then alive to have attended their funeral, laid wreaths. Of the over-100 identified commemorative sites associated with the war in Clare, monuments concerning the Scariff Martyrs have generated the most consistent commemorative activity in the county.40 Despite the Covid-19 restrictions imposed in 2020, the centenary was marked by the East Clare Memorial Committee, in both Scariff and Killaloe, where latterly a ceremony was held exactly 100 years to the moment of their deaths on Killaloe bridge.41

‘Rang from Shore to Shore’ – Song and Story

The story of the Scariff Martyrs was not told alone within the embrace of the east Clare landscape but often travelled to distant parts of the world where people of that area voyaged. In the early hours of 28 January 1993 in the Lord Newry Public House in North Fitzroy, Melbourne Australia, the last singer of the night cleared his throat. He had sat respectfully as thirty previous compositions had been offered by musicians from all across Ireland who were then living in Australia.

Joe Fitzgerald from Corigano in east Clare was encouraged to add a thirty-first and final composition. The east Clare man did not have to think long for his selection and drew the lonesome lament of the Scariff Martyrs all the way from the mountains of east Clare to the shores of Australia. Helen O’Shea, later an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne was present that night and was taken with the emotion in Fitzgerald’s rendition, describing it as ‘impassioned and dignified’.42 As a teenager in the 1950s, Joe Fitzgerald had sung the song within his own community shortly before he and his entire family emigrated to Australia in the early 1960s, leaving their mountainside home to fade with time.43 In October 2018, an open-hearth fire warmed that home once more, as Joe Fitzgerald spoke to me in the house he had restored, about his connection to the song:

When I heard the song first, it was from a man called Joe Joe Guerin down in Baba McCormacks [Tuamgraney]. The song is about four famous men and four great men who fought for our freedom and died for our freedom and they gave us the freedom to roam these mountains, the mountains of Corigano and Caherhurley at our will, without anyone telling us what to do in our own land … When I heard the song, I thought, these men gave us freedom and why not sing about them … I love singing that song and I sang it in Australia and I sang it in England! Maybe there’d be a few that wouldn’t like to hear it but I don’t care about that so much. I’d sing it anyway!44

‘The Scariff Martyrs’ was made nationally popular when it was sung by Irish singer/songwriter Christy Moore in the 1970s.45 Moore first heard the ballad in Murphy’s pub in Tulla in 1964 and also spoke to Teddy Murphy’s mother, who had attended the funeral in 1920.46John Minogue, from Kealderra in Scariff, recalled being taught the song in Cooleen Bridge National School early in the 1930s by Bridget Cuneen, who was the sister of Margaret Hoey, mentioned earlier.47 At the same time as Minogue was learning the song in an east Clare school, Rody O’Gorman, a twelve-year-old pupil from Derryoober, Woodford in Co. Galway, wrote the full song as his contribution to the 1938 School’s Folklore Scheme.48 The ballad was known well in that area and was sung later by both Harry Nevills and Michael Joe Tarpey.49 Musician Cyril O’Donoghue included a musical version of the song in his 2003 album Nothing but a Child and described the way in which exposure to the song as a young boy led him to adopt it in his music much later:

With regards to the song, I first heard it as a child sung by my father [Paddy O’Donoghue] in a pub in Broadford late one night and he told me the story of the killings and later heard it sung by another man in Bodyke who my father got it from. It always stuck in my mind.50

Several contributors recall hearing the song at social occasions, such as during ‘the Cuaird’, a nightly social visiting practice in rural Clare.51Anna Mae McNamara took me in the 1950s to the mountains above Tuamgraney:

I remember as a child hearing my uncle Thomas Hill sing the Scariff Martyr’s song in Ballyvannon at a house dance. That would have been the mid-1950s and I can still recall the respect people gave my uncle when he was singing the song. The ‘Scariff Martyrs’ seemed to mean the most to the people there.52

However, J.P. Guinnane and Paddy Clancy from Kilkishen revealed that the song was not immune to opposition. J.P. explained how, on one occasion, a man called Mikey Quinn was singing the song in a public house in Oatfield when a former Black and Tan, who had stayed in the area, interjected and stopped him.53

Still, as explained by the daughter of one of the East Clare IRA’s most active members, Martin ‘The Neighbour’ McNamara, if one wanted to find out about the Scariff Martyrs ‘you’d get it all in the song’.54Tom Lynch, a native of O’Callaghan’s Mills also recalled ‘a Hussey girl from Bodyke’ deliver the song in Lucas’ pub in Whitegate and remembered how ‘you could hear a pin drop’.55

While the song is well known and has since been covered by established artists, its origin is unclear.56 The local contention is that Jamsie Fitzgibbon, a native of Ballyhurly in Ogonnelloe was the composer.57 However, in a collection of papers, belonging the Rodgers family, the origin of the composition is contested. An original hand-written version of the song was sent to Mrs Rodgers on 8 March 1922. An associated letter claims that ‘D.P. O’Farrell’, who described himself as ‘The Ogonnelloe Poet’, was the songwriter. He also disclosed that he wrote the song on Christmas Eve 1920, less than two months after the incident, lamenting that ‘a copy of some sort’ had already been circulated locally. He explained that his reason for writing was that he wished for the family to have ‘a correct version’ of the song, before declaring that ‘they never fail here or beyond who fall in a great cause’.58

The song has performed a critical role in terms of both knowledge and sentiment. The infusion of a deep lament into the lyrics and tone of the song resulted in a repeated invocation of sadness across the decades, summed up in its characterisation by McLaughlin’s as ‘a bitter lament that tugs hard at the emotions’.59

A number of later songs were also composed to com- memorate the men and the incident. For example, Jack Noonan, a well-known poet from Killaloe, composed ‘The Four Who Fell’, which is written from the Killaloe context and was popularised by The Shannon Folk Four.60 Interestingly, in an indication of the influence of songs on social memory, research finds that where interviewees from the north-east Clare area surrounding Scariff, refer to the men as ‘the Scariff Martyrs’, in Killaloe, they are referred to predominantly as ‘The Four Who Fell’.61 When Lena McGrath returned from Sheffield for her annual holiday, she would recite a poem she learned in the late 1920s in her native Gurtaderra, outside Scariff. Lena would deliver one particular verse with an appreciably greater intensity, referring to ‘Alfred Rodgers’ with ‘a soul so pure and grand’ proudly proclaiming each time that Alphie was her godfather.62

A confluence of song, monument, commemoration and story has generated a powerful memory which elevated the men to hero status within the local community. Other methods too were employed to preserve their story. Memorial cards have been an important method of preserving the memory of fallen republicans. In August 1921, the family sent a photograph of Alphie Rodgers to J. Stanley Photography Studio in Westmoreland Street in Dublin, where 200 mortuary cards were produced at a cost of £2.63 When his nephew Fr Manus Rodgers was a teenager in St Flannan’s College, he noticed a fellow pupil from Portroe in Tipperary with one of those cards in his prayer book.64

The admiration in local social memory for the Scariff Martyrs was potently reflected in interviews I carried out over from 2000 to 2020. Tom Lynch, born in 1929 recalled ‘they’d talk with reverence and they’d nearly pray for them’.65 For Michael O’Gorman ‘There was great reverence like. If they could have canonised them they’d have done it’.66

Two emotions predominate in stories about the Scariff Martyrs: pride and sadness. For those closest, the latter was overpowering. From the lowered head and perpetually sad countenance of