0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The Sixth of June tells the story of American soldier Brad Parker, who joins the U.S. Army to fight in World War II. When he arrives in London, he meets lonely Valerie Russell, and they fall in love despite their loyalties to wife and future husband. Although they are certain that their love could overcome every obstacle, everything changes after the Normandy Invasion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

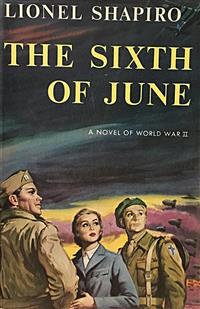

The Sixth of June

by Lionel Shapiro

First published in 1955

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Sixth of June

by

THERE IS A LAND

blest with the heritage of knowing intimately her British kinsmen and her American neighbors and of loving and in a sense uniting both.

The land is Canada, and it is to this precious heritage that I dedicate gratefully this book.

Author’s Note

A DECADE is so short a passage of time in the sweep of recorded history that the use of the word historical in connection with this novel seems at first glance a literary impertinence.

Nevertheless I like to think of this as a historical novel. The fact that most adults now living recall World War II as a personal experience does not, in my opinion, apply as a disclaimer. This is certainly a historical novel from the standpoint of the methods of warfare here described which are not dissimilar to those employed at Ypres, Belleau Wood, and even Bull Run, the only differences being the numbers of men involved, the speed of their machines, and certain imaginative advances in the efficiency of essentially ancient forms of weapons. One need only consider that the great operation code-named Overlord would have been pricked like a child’s balloon by a single strike from any one of a score of modern weapons.

There is another point. The trauma into which we have been flung by the advance of science has endowed our memories of 1942, ’43, and ’44 with an incredibly romantic aura which is the vital element of the historical novel.

It is therefore scarcely necessary to add that the persons depicted herein, and the units and staff sections, belonging as they do to so simple and sequestered an epoch, could have been rallied into the structure of this novel only by use of the author’s imagination. Except for certain names long recognized by history, these persons do not and did not exist.

BOOK ONE Two Farewells

1

A later call on President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, a guest at the White House, was no more than an informal chat. . . . Tobruk, in the African desert, had just fallen to the Germans and the whole Allied world was thrown into gloom. . . . General Clark and I, with a few assistants, left Washington in late June 1942. This time the parting from my family seemed particularly difficult although it was, in a sense, a mere repetition of previous instances covering many years. Our son came down from West Point; he, my wife, and I had two days together, and then I left.

—Crusade in Europe, by Dwight D. Eisenhower.

SO MANY were leaving, so many and mostly so young. They poured out of their homes and moved urgently to the last barricades, for the war was nearly three years old and the lesser barricades had already been overrun. They were all sorts and sizes and shapes, these men who were to be twisted into a solid mold of olive drab and khaki; the eager, the laggard, the brave, the sensitive, the frightened, the kind, the cruel, and the noble, in such myriad variety and combination that the important personages who pondered global charts and issued global orders must have felt a trifling of what it means to be God. So many paths were to be crossed, so many were to die, so many to live and perhaps learn.

From where Lieutenant Brad Parker stood, on the railway platform at Malton, Connecticut, his global view was somewhat constricted by a group of thirty relations and friends.

His handsome wife, Jane, stood beside him neither snugly nor coldly but with a sure sense of possession, and the first semicircle that faced him was composed of his father-in-law, Damien Lakelock, who was publisher of the Malton Daily Star, his mother-in-law, Grace Lakelock, and his own mother, Delilah Parker. The other people, as though sensitive of the occasion’s protocol, had arranged themselves in distinct waves. Behind Brad’s immediate family stood his distant relations, then close associates from the business and editorial offices of the Daily Star, and in the rear, intimate friends. Standing on the edge of the group were two men who didn’t quite fit into any of these categories. They were Sanford Jaques, the congressman for Malton and district, and old Abe Maxted, a typesetter who was president of the newspaper’s Quarter Century Club of which Brad, as prince consort, was an honorary member.

The two fifty-one for New York was already ten minutes late. Everything that needed to be said had long since been said. The midafternoon sun, slanting beneath the platform’s roof, set the men to perspiring and the women to fanning themselves with their handkerchiefs. Since no one dared, for fear of betraying boredom, to peer down the track in search of the train, they all looked at Brad in a solemn and respectful way that might have thrust upon a stranger the impression that the personable young lieutenant was unique among Malton’s 215,000 population in leaving “to take his place of duty on a far and lonely rampart.”

The phrase had appeared that morning in the Daily Star’s leading editorial and had been composed more or less in honor of Brad’s departure for Britain although it was circumspectly used to cover all of Malton’s young men who had gone or were preparing to go to war. Its eloquence was only part of the tribute arranged for the occasion.

There had been a luncheon in a salon of the Pentland Hotel, across the square from the station, and this, like the editorial, was privately savored by Brad’s family and a few friends. Congressman Jaques was present and also Ben Carver, the Daily Star’s venerable editor. Damien Lakelock had gone so far as to instruct the city desk that no mention of the event was to appear in the paper, not even in the society notes, thus breaking, though not seriously, the distinguished journal’s sixty-year tradition that the executive tower does not meddle with the content of the news columns.

The luncheon had gone off well. By and large, its bittersweet atmosphere could hardly have been improved upon. It had progressed with a murmur of conversation sparked now and again by polite laughter as if all present were conscious of a duty to be normal and cheerful. There had been a hush when Ben Carver raised his voice slightly to deliver his opinion that the choice of an unknown general to command in Europe was another of Roosevelt’s gambles with the nation’s destiny, but Congressman Jaques promptly responded that under the American system a leader was only as effective as the effort behind him, and when Washington assigned young men of Brad Parker’s caliber to the headquarters staff in London, nothing much could go wrong with the effort there. Ben Carver grumbled “Hear, hear” to this, and the proper atmosphere had been restored. Brad’s mother held her handkerchief significantly high, but not too high, on her cheek as she whispered something to Mrs. Lakelock. She managed, however, to smile when she turned around to glance at her son. Then a waiter served brandy along with the coffee and an expectant silence fell on the gathering. Damien Lakelock turned quite informally to Brad. He said, “Well Brad, the publisher is going to miss the assistant to the publisher, and so, I’m sure, will all the rest of us. Godspeed, good luck, good hunting, and come back safe and sound when the job is done.”

That was all. Brad nodded his thanks, his mother jabbed hurriedly at her eyes, Ben Carver managed to catch the waiter’s eye for another quick brandy, and then it was time to walk across the square to the station where a group not invited to the luncheon awaited the final act of farewell.

Now, as they stood on the platform, the bittersweet flair was being undone by a blazing sun and a laggard train.

Brad scanned the faces that looked upon him with such well-behaved glumness. He felt a curious elation, soaring but secret, and he had to withhold himself not to parade it openly. Being a sensitive man, he knew that elation was a wrong, even a sinful way to approach war. But he was also an honest man. The war had come at the right time for him, exactly at the right time. Five years ago would have been too soon; at twenty-one he was too young, too ambitious, and there was gamble enough in reaching out blindly for a career. Five years hence might well be too late; a mature marriage, perhaps children, and the tentacles of the Lakelock dynasty might have smothered any urge for a fling with adventure. At twenty-six, for reasons he dared not admit to himself, the time and the war fitted perfectly.

His Aunt Ellen, of the Parker side of his family, had unwittingly put it into words at the luncheon when she whispered, “Don’t you feel grand, Brad? You must. First Lieutenant Bradford Gamaliel Parker, United States Army—it just sounds so wonderful!”

It was wonderful to a man who hadn’t enjoyed a real chance to flex his muscles and was already weighted down as assistant to the publisher, heir apparent to the executive tower, president of the Junior Chamber of Commerce, and a director of the Country Club. The thought that he might be killed in the war occasionally entered his mind and he dreaded it, but there was also comfort in it for the greater the risk the less guilty he felt for being elated.

His gaze fell on his father-in-law’s gray, distinguished face. He thought he detected a wry smile. Their eyes locked for a moment and he knew that Damien was sharing his secret, that the wry smile was a smile of envy, of chagrin for a long ago chance that was lost. Damien had been in the same position in the first war, married to Grace, the only child of Everett Bolding, founder of the Malton Daily Star. But Everett had been a tough old puritan, a power in New England politics in a time when power could be nakedly wielded, and he saw to it that Damien’s uniform carried him no farther than a desk job at the Boston port of embarkation.

He too had felt something of that frustration when they called him up as a reserve officer just after Pearl Harbor. He had volunteered for the Special Service Force, training in Helena, Montana, in parachute and winter warfare, but Jane had gone along to live with him in married officers’ quarters and there were monthly leaves home and constant telephone conversations with Malton, and at least the suspicion that he might remain stateside as an instructor. Now, inexplicably, the War Department had given him a fortnight’s embarkation leave and had reassigned him to London. He was going to have his war at last.

He could almost hear Damien murmuring, “You’re lucky, Brad. You’re lucky I’m not old Everett. I didn’t fix it. There’ll be time enough when you come back, a whole lifetime, to be chained to the women who surround you, and to the paper and to the community.”

A crusty voice called out, “Careful, folks!” and they all moved aside to make passage for a mail cart moving to the head of the platform. Then a train whistle sounded. The faces peering at Brad became animated.

Jane whispered, “Thank heaven. I thought it would never come.” She lifted herself closer to his ear. “Don’t forget to fuss over your mother. I think she’s furious about not coming on to New York.”

They had broken ranks now and were all around Brad, slapping him on the back and making brisk, jocular remarks, but most of what they said was drowned in the roar of the engine as it rumbled past them.

Brad kissed his mother on the mouth and then on the cheek. She said, “Brad—Brad—it’s not the war or the danger. I know you’ll come through all right. It’s your health. You give yourself so much to anything you undertake——”

He kissed her again. “Just take care of yourself, Mother, and don’t worry about me.”

Then he kissed his mother-in-law. He thought he detected a furtive note as she said simply, “You’ll write Jane often, won’t you?”

Damien didn’t say anything. He shook hands with Brad and smiled the same soft envious smile.

The Lakelock chauffeur was already handing up Brad’s baggage and Jane’s overnight case to a Pullman porter.

“Good-by, everybody,” Brad called out. “Write you from Berlin around next Thursday. Might be a day or two late.” They all laughed. He took Jane’s arm. “Come on, dear. Up you go.”

Standing on the platform of their Pullman as the train moved slowly out of the station, they appeared to the farewell party as fine and decorative as the American dream itself.

Brad wore a tan summer uniform, exceedingly well cut by his own tailor, and his blouse already bore a metal parachute insignia above two efficiency decorations. Moreover he looked the part. His lean, well-shaped face was virile rather than handsome; he was attractive (as Grace Lakelock described him to her friends when he was courting Jane) “in a wholesome way—no airy-fairy foreign good looks but solid New England.” His nose was certainly New England, straight but neither thin nor small, and his blue eyes, when they looked straight at you, were inclined to hardness. He had healthy black hair, a determined mouth, and a distinct cleft in his chin. He carried his six feet so well it was hardly noticeable that his shoulders were disposed to roundness in the manner of a man hurrying toward success.

Jane was big for a young woman, something over five feet seven and inclined to be fleshy at the hips and bosom. The features of her face too were generously large but she carried herself with style and no little verve. From the time she was a child, her parents had taken an honest view of her developing ungainliness, and they pushed her through years of planned exercise and ballet and dancing classes until she had attained an unusual degree of gracefulness. This, in addition to her finely shaped legs and a lavish budget for clothes and coiffeur, had made her into an extremely desirable woman. Now, at twenty-four, she was at her best. On this day she wore a silk print dress expertly tailored to amend her less attractive lines, and her thick brown shoulder-length hair swept daringly to one side, her right, setting off her better profile which was her left. Altogether she looked a magnificent companion piece to the officer who was her husband.

They waved and waved, and when the train had passed the head of the platform she said, “I’m sorry, darling. It was all too precious. I need a drink—a real big fat drink.”

The parlor car was a madhouse of activity and high spirits. Businessmen, tourists, and soldiers and sailors of all ranks up to brigadier general filled every seat and overflowed into the passageway. On a writing desk in a corner two WACs had set up a portable gramophone. A cluster of GIs joined them around it and all gestured to the music with their hips and their hands. Every ash stand was equipped with a serving rim and these were covered with drinks and dollar bills. Two Negro waiters, grinning and perspiring, ran a marathon between the pantry and their demanding clients. Like every other corner of America at war, the car was shot through with a sense of animation and well-being.

Brad congratulated himself on having had the foresight to reserve a drawing room. When he and Jane had seated themselves in the quiet, air-cooled room, he rang for a waiter.

“I want service,” he said to the breathless Negro, handing him two dollar bills.

“Service you’ll get,” the man replied. “Jes’ give the order, General.”

By the time the train reached New Haven, Jane was on her third whisky. Brad, still toying with his first, watched her quizzically. She didn’t like liquor. At parties she usually sipped at a single drink the whole evening and then only because the young married crowd in Malton drank freely and she wouldn’t have them think she was better or more respectable even though she was the Lakelock heiress.

Now she had taken a gulp out of her third drink and her eyes, still clear, stared out of the window. The pose was handsome, decorative, and full of hurt.

Brad reached across the table, took the glass out of her hand, and played with her cold finger tips.

“What is it, Janie? Come on, dear. Out with it.”

She gave a little shake of her head. He waited. Then, still staring out the window, she said, “Our three years together have been good years, Brad. I’ve been happy.”

He smiled. “Don’t try to jinx me, honey,” he said deprecatingly. “They’ve been wonderful years and there’ll be a lot more—so many more you’ll be damned good and tired of me. I can just see you about thirty years from now, saying, ‘What did I see in this goat when I could have married Cary Grant or somebody like that?’ ”

She turned and looked at him squarely. It was an honest and affectionate look. There was a nakedness in it she rarely brought herself to expose even in the act of love.

“I’m not unhappy about your going, not desperately unhappy, not the way I suppose a wife should feel when her husband is off to war—and I’m not trying to jinx anything, Brad. You’ll come through all right. I was never surer of anything in my life. But—oh I wish I hadn’t had these drinks. I’d explain myself better——” She snatched her glass and took another gulp and pushed the glass away distastefully. “It’s just that I’m losing you. I’m losing you, Brad. I’ve had the feeling during the whole two weeks of this leave that you can’t wait to get away, to get away from everything, from Malton and from the paper—and from me.”

He was shocked by her perception. In their three years of marriage they had been honest enough with each other, although the true depth of their honesty had never been tested. There had never been need for it. They had been happy in the glare of attention that played on the early years of a brilliant match, and this happiness carried over adequately into their private lives together. She had been a proper, even a delightful wife, possessive in a way that complimented rather than imprisoned him, proud of his achievement though it had been mostly the gift of the dynasty he had wedded, and charmingly boastful, in the subtle ways young matrons have of communicating these matters among themselves, of his virility.

Now, in their first emotional crisis, she was showing a depth of feeling he had never suspected in her.

He said, “You’re my whole life, Janie, and so in a way is the paper. You know me well enough. I don’t run out on anything. I never have. I’ll be honest with you——”

She squeezed his hand impulsively. “I don’t want to hear it, darling. Whatever it is you’re going to say, I don’t want to hear it.”

He knew he hadn’t struck the right note. He had hurt her. He said quickly, “I love you, Janie, and I also want to get off to the war. You’ve got to be a man to understand it. Look, darling, war happens to an American once in a lifetime. I don’t want to read about it in the papers, even if I’m wearing a uniform. I’ve got to see it and be a part of it, and be lucky enough to come out of it. That’s why I fidgeted when they were trying to make me out some kind of martyr. I’m no hero. I’m just curious.”

She pulled her hand away gently and took another sip of her drink.

She said, “I’m glad they’re sending you by plane. It’ll be nice and symbolic seeing you off flying tomorrow. Then I’ll come back to Malton and wonder how it will be years from now when you come back. I’m getting good and tipsy now, darling.”

“Years from now?”

“Yes, years. The Germans have got everything from Leningrad to Spain and the Japs are sprawling all over the Pacific. We’ll win it—but years, darling.”

The train rattled across the Connecticut countryside. Brad finished his drink and ordered another for himself. They didn’t speak for a time.

Then he said boyishly, “How did you know I wanted to go so badly?”

“I knew it”—she smiled a sad, wise smile—“because I know you.”

“Come on, Janie. You can’t know me that well. Not in three years.”

“Think you know me?”

“Not completely.”

“But I know you. That’s because I love you. Shhhh! Don’t argue. I haven’t been this gay in my life so let me talk. It’s your going-away present to me. Let me talk. You didn’t marry me, Brad. I married you. It couldn’t happen any other way. I couldn’t marry Cary Grant or some band leader. I had to marry a man who would someday be publisher of the Star. And then you came along and I fell in love with you and it was too good to be true because I wanted you and you fitted. You fitted perfectly and on top of it I loved you. What came first, the chicken or the egg? Did I love you first or did I know you fitted and then fell in love with you? I knew. So I blitzed you. You didn’t know I blitzed you, did you? I never intended you to know, and you never would have known because the years were going to be so full and fast you wouldn’t have time to realize what had happened to you, and when we were old it wouldn’t matter any more because by that time you’d really be in love with me. Oh, I had it planned, beautifully planned. And then the war has to come along and the Parkers have always gone to war, always, back to ’76 I suppose, and Janie’s fifty-year plan goes bang after three little years. I feel silly and wonderful and I’m making a ridiculous spectacle of myself. Forgive me, darling. Don’t say anything. Please don’t say anything.”

She pushed her glass toward him. Her eyes were shining. She smiled and said, “Don’t look so shocked. You drink it, darling. I hate the stuff. I really do. You see what it’s gone and done to me.”

He took her drink and smiled at her, and like embarrassed children, their smiles became too abundantly gay. He leaned across the table and puckered her lips with his fingers and kissed her lightly.

She said, “Don’t let me drink any more. And no more weepy conversation—oh, I almost forgot. I’m supposed to tell you that you’re to sign the bill at the Waldorf. It’s Daddy’s gift. And the dinner at “21” is mother’s, and your mother got us the tickets for the Gertrude Lawrence show. Wasn’t it sweet of them?”

“Terrific. I suppose though I’ll have to shell out for the checkroom.”

“And Brad——” She looked away quickly. “I’ve got a gift for you too but let’s wait till later. I’m almost afraid to give it to you now.”

The train was rolling through Greenwich and her eyes found refuge in a row of billboards advertising the Broadway shows. It was coming up to four o’clock as the train passed Greenwich Station.

2

IN ENGLAND it was coming up to nine o’clock in the evening.

The sky over Lincolnshire had been overcast all day, and now dusk brought with it a gentle rain that whispered softly as it fell on the eaves and gardens of the village of Burlingham. Along High Street, which stretched a quarter of a mile between the railway station and the common, blackout curtains had already been drawn. The only light to be seen was a tiny red glow which marked the entrance to the village pub, The Stag at Bay, and even this minuscule break in the blackout pattern, although permitted by the authorities, disturbed the elderly residents of Burlingham because German planes lately had been prowling the skies in the vicinity of the R.A.F. Bomber Command station at Belnorton, four miles to the east.

Burlingham’s middle class, in large part retired merchants who had fled the bustle of Lincoln, population: 70,000, lived in houses which ringed the common. These were mostly two-story dwellings, low, wide, stolid, and so encrusted with pampered plant life that one might suspect they were never built by man but grew naturally out of the soil of England. Unlike the homes on High Street which were identified by number, these on the common bore only a charming and usually illogical name plate. “The Cottage” was in fact the finest and largest house in the village, and “Hillview” and “The Moors” had no visible connection with hill or moor.

On this evening, as the day’s last light glistened feebly on the wet fields, an ungainly, mud-spattered military vehicle called a 1500-weight rolled into Burlingham, traversed the deserted length of High Street, circled the common, and came to a halt in front of a house, half hidden by trees and wrinkled with ivy, which bore the name plate “Darjeeling.”

Captain the Hon. John Wynter sprang from the vehicle.

“I’ll be about half an hour, Bailey,” he called back to the driver. “I’ll try to arrange tea for you.”

“Thank you, sir,” the driver said.

The captain pushed open the gate of “Darjeeling,” passed along a path rimmed with rosebushes and violas, and pulled at a bell beside the blacked-out door.

He had a slim figure, even wearing the coarse cloth of British battle dress, and he appeared taller than his five feet, nine inches. His blond hair bulged thickly from under the headband of a green beret, and his eyes, pale blue and inordinately mild, looked out rather sadly from a face that was tanned and weather-beaten. His features seemed a bit too finely shaped, the nose too thin and the mouth too sensitive, for the rough masculinity associated with his shoulder patches which bore the legend Commando. He looked younger than his twenty-seven years.

He pulled off his beret as the door was opened by a tiny, dark-skinned woman with hair of pure white. She wore a severe black dress, and from her left shoulder flowed a section of bright maroon cloth which gave the impression of a sari.

“Good evening, Mala.”

“Captain Wynter! Do come in out of the rain.”

John hesitated. “I’m afraid it’s a rather impolite hour, but I couldn’t get through on the phone——”

“I am sure you will be welcome. Do come in.” Like all Indians who speak English well, she articulated her words with quiet authority which was altogether pleasant. She closed the door behind him and pushed aside the blackout curtain which cut off the vestibule. “The brigadier is always pleased to see you,” she said with a faintly proprietary air, “to say nothing of Miss Valerie.”

“Oh good. Then she’s here too.”

The tiny woman led the way through an entrance hall to a living room which was neatly but inexpensively furnished. She said, “I daren’t disturb the brigadier while he’s listening to the news——” She smiled obliquely. “But I’m sure Miss Valerie won’t mind.”

Her guile was lost on John. He nodded solemnly and said, “Mmmm, I hope not.” He added hastily, “By the way, we’ve done about two hundred miles today and my driver is out there. I—I wonder——”

“I’ll see to it, Captain. Tea?”

“That would be splendid.”

She left, and a few moments later Valerie Russell came into the room.

“What a wonderful surprise, John,” she exclaimed. She came across to where he stood and extended both her hands. He took them in his hands, and his face was so modestly happy it was almost sad.

He said, “It’s good to see you, Val, but I think I should explain. We left Inveraray this morning and when the colonel gave me permission to break out of convoy at Doncaster, I tried to get you on the phone but the trunks into this area seem all tied up, and—well——”

“Bother the trunks,” she said lightly. “It couldn’t matter less. It was grand of you to come.” She gave his hands an extra little squeeze and went to a sideboard for a sherry decanter and glasses. “You look absolutely fit. Commando training must suit you.” She placed the sherry and glasses on a serving table. “Now do sit down and tell me all your news.”

He didn’t sit down, nor did he speak at once. His pale blue eyes studied her as she concentrated on pouring two glasses of sherry.

She was the loveliest girl he had ever known; indeed, the loveliest he had ever seen. Middling tall, she possessed both suppleness and carriage in unusual harmony. Her light brown hair, which contained a slight tint of red, swept back severely from her forehead and was gathered up in a tight bun at the back. John felt this was just as it should be. When she allowed her hair to fall into its natural waves, as she had on one occasion early in their acquaintance, she was too strikingly beautiful for his taste. This hairdo, to his way of thinking, was just right. It was severe enough to lend a classic line to her features, and it rather offset her lips, which were generous with a most un-English fullness, and her deep, darkly brown eyes which were foreign to her pink and white complexion. It was as if the place of her birth, which was Darjeeling in India, had invested her with something of its agelessness. At twenty-two her face possessed a maturity and strength of one who has lived a long time and has witnessed much.

The gray cardigan and tweed skirt she wore on this evening failed to make her look typically English. She defied classification, John thought.

She handed him a glass of sherry. “You must excuse Father for a few minutes. He still marks up his war maps, the poor dear, according to the BBC reports.”

“How is he, Val? Really.”

“He seems improved—at least physically. Even the scars are healing over. The trouble is, the stronger he gets the deeper he falls into his peculiar bitterness. I don’t know——” She looked into her sherry glass. “They’ve really retired him, haven’t they?”

John said, “He’s still on the sick list—officially, that is. But—well, things have changed. War isn’t the same and Britain isn’t the same.” He looked up and smiled sadly.

She said, “You mean old Indian army officers are no longer in style.”

“More or less. Pity. He’s a wonderfully brave soldier.”

They fell into silence. Then Valerie said brightly, “Do forgive me, John, nattering about Father. Are you happy with the Commandos—you certainly look as if you are—and how did you ever manage to break off convoy at Doncaster?”

He didn’t want to look at her when he told her the news. His eyes fixed on a brigade pennant framed over the fireplace.

“It was a sort of embarkation privilege. You see, Val, I’m off.”

“John! On operations? So quickly?”

He nodded. “It’s really grand news.”

She said slowly, “But it isn’t true! The division hasn’t been training more than a month or two.”

“Oh, the division isn’t going. Just a reinforced company, sort of small Commando. That’s what makes it so splendid. They picked my company, Val.”

Valerie stood. She took a step toward the slim young man, then walked slowly away toward the fireplace.

“Yes, it is splendid.” She smiled briefly. “I suppose you can’t tell me where or when.”

“Wish I knew,” he said cheerfully. “We rendezvous at Aldershot tomorrow afternoon and—well, I suppose it’s safe enough to tell you, Val—we proceed to a southeasterly port for embarkation. You know what that means.”

“Then it isn’t a coastal raid.”

“I’m sure of that. It’s overseas operations.”

“The Middle East?”

“Good guess, I imagine. We won’t know till we break open our orders a hundred miles, or some such figure, out to sea.”

John brought his head up and allowed himself to look squarely and unashamedly at Valerie. She came across the room and sat on the arm of his chair.

She said, “How long can you spend with us?”

“I should be off in ten or fifteen minutes.”

“But John! You may be away for months!”

He took her hand. “I know it’s a bit of a rush, but I’m luckier than most chaps in the company. They can’t get home at all. The orders came through only last night.”

“It’s not fair! It just isn’t at all fair. It’s a filthy way to run an army.”

He smiled shyly. “It’s not really bad, Val. Between Bailey and myself, we can drive all night and make London early enough to give him a couple of hours with his wife. Then we’ll pop down to Tunbridge so I can see my father for a bit, and we should hit Aldershot dead on time. Works out rather well.”

Valerie said, “Then we’d better go in and see Father.”

“Won’t he mind being interrupted?”

“He’s very fond of you.”

They passed through the hall and paused at the door of the brigadier’s study. The nine o’clock news was still on. “. . . at this afternoon’s press conference, a spokesman for the War Office made no attempt to minimize the loss of Tobruk, but he appeared to take a much more serious view of the effectiveness of the new 88-millimeter cannon the Germans are using on our tanks. Their firepower from positions of almost perfect concealment cost the Eighth Army fifty-seven tanks in the last two days of fighting. According to our correspondent in the desert . . .”

John whispered, “Oh Val, do you think, afterward, we might pop across to the pub? One drink. Just the two of us.”

“Of course, John. I want to.” She knocked lightly on the study door and opened it.

The brigadier paid no heed to the interruption. He sat stiffly in an armchair and stared ahead at the blackout curtain which covered a full wall of the small, square room. He was a tall man, three inches over six feet, thin and big-boned, and his cropped, steel-gray head framed the face of a born warrior. It was a lean, knobbly face with a steel-gray brush mustache and eyebrows and a chin which jutted belligerently as he listened to the wireless. Only the eyes betrayed the warrior. They were small, spiritless eyes which stared dully from dark circles of discolored skin. On the right side of his face, a pattern of ugly keloid scars scampered across his chin and neck and was lost beneath the collar of the tropical bush jacket he wore.

“. . . As a result of our evacuation of Tobruk, the Afrika Korps under Field Marshal Rommel now controls the entire stretch of Mediterranean coastline as far east as Alamein. However, as the enemy does not control the sea or the air, his overland supply line is vulnerable to the type of raid——”

“Father.”

“For God’s sake, girl, can’t you see I’m listening?”

“John is here.”

“Well, can’t he wait? Shush——”

“. . . Commenting on the fall of Tobruk, Reuters correspondent observes that while the situation is serious, it is by no means devoid of hope. The arrival of increasing supplies of American Sherman tanks with their high speed and improved maneuverability——”

“He has only a minute or two.”

“Dammit, Valerie, I don’t see——”

“Father, he’s off overseas. To the Middle East.”

The brigadier reached a long arm to the wireless on his desk and turned it off. “Serious but by no means devoid of hope,” he scoffed. “These piddling experts! What do they know about it?” He turned about and when he saw John standing behind Valerie he nodded and his mouth lost its scowl.

“Come in, Wynter.”

“Thank you, sir.” John dropped his arms stiffly at his sides for a quick moment and entered the room. “You look fit, sir.”

“I’m quite all right.” Brigadier Russell smiled narrowly as he studied the junior officer. “Sit down and tell me about this Commando of yours. Is it any good?”

John glanced at his watch, then at Valerie. He sat on the edge of a chair and detailed his company’s stiff training schedule. Encouraged by the brigadier’s approving nods, he brought himself to say, “We’ve got beach assaults down to a pretty fine point, sir. I put a stop watch on my engineer platoon at Inveraray yesterday. From the fall of the ramp to the laying of a bangalore thirty yards up the beach took them exactly nine seconds.”

“First class. Absolutely first class.” The brigadier’s eyes took on an unaccustomed sparkle. “And now, Valerie tells me, you’re off to the Middle East.”

“We’ve had emergency embarkation orders. I can only guess it’s the Middle East.”

The iron-gray face clouded over.

“Are you in the habit,” he thundered, “of spouting emergency embarkation orders to your friends? By God, Wynter! I thought I taught you better.”

John said, “I see what you mean, sir. But it’s rather difficult to be going off for months or years——”

“What’s difficult about it?” the brigadier demanded. His chin came up and the keloid scars on his neck stood out inflamed and ugly. “We’ve become a bunch of ninnies. That’s the trouble. Ninnies!”

Valerie said, “Oh, come now, Father. It’s my fault and it’s not at all serious.”

“You keep out of this, Valerie.” The brigadier’s mouth hardened and he clenched his fists as if trying to control an emotion that was overtaking him.

“Ninnies!” he growled. “The whole damned lot of us! Can’t do this, can’t do that! Sit here and pinprick the Hun with a bomber or two! Fall back on the desert like a lot of cowards! Beg the Americans to come over and help us! The Americans, by God! I remember them in the last party. Running up three divisions to attack on a brigade front! Can’t die. That’s the trouble with the Americans. Never could. Always had to raise the odds on dying. Ninnies! Every last one of them!”

The iron-gray man took to staring at the blackout curtains and his eyes blinked incessantly. John looked to Valerie. She made a hand gesture as if to say, let him go on, don’t try to stop him.

“We should be standing up to the Hun,” the brigadier grumbled harshly, “standing up to him and driving him back. You remember St. Omer. You decoded the order yourself. You did, didn’t you? Fall back on Dunkerque. What nonsense! Fall back on Dunkerque! I said, stand and fight! Attack! Cut off their damned line at Béthune! Or die! When the British can’t stand up to the Hun, then die!”

He kept staring at the blackout curtains.

“If I hadn’t caught their shrapnel, I’d have gone on ignoring the damned order——” Now his voice turned faint and strangely plaintive. “But my 2IC was a ninny. Bundled me up and rolled me back. Didn’t have the decency to leave me there—leave me there with the men who obeyed my order to stand and fight—didn’t have the common decency.”

He blinked his eyes faster.

“You know, Wynter, why they’re keeping me on the sick list. Two years and still on the sick list. When I go back they’ve got to give me a division and they’re afraid to give me a division. They’re afraid I’ll fight. You know that, Wynter. You know it, don’t you?”

John said, “I hope you get your division, sir. I’ll be proud to serve with you again.” He glanced anxiously at Valerie. She went to the back of her father’s chair and passed her hands softly across his shoulders. He was panting like a spent bulldog.

John got up. “I’m afraid I have to leave now, sir.”

The brigadier didn’t look at him. “You’ve the makings, Wynter. I haven’t forgotten St. Omer. Get out there, wherever you’re going, and come to close quarters with the Hun. Close quarters, you understand. It’s the only way. A bit of the bayonet is better than ten thousand of these playthings that take off from Belnorton every night.”

“I understand, sir.”

“All right. Good luck.” The brigadier shook off Valerie’s hands and stood up. He towered over the captain as they shook hands but his gaunt frame swayed slightly and the steel-gray head with its black eye sockets was a shell.

Outside it was black as pitch, and silent except for the feather whisper of rain. Valerie and John walked blindly down the cottage path until their outstretched hands touched the gate. They could barely make out the hulk of the 1500-weight parked in the roadway.

John called out, “Are you there, Bailey?”

“Right here at the wheel, sir.”

“Had your tea?”

“And sandwiches, sir.”

“We’ll have to drive all night. Feel up to it?”

“Piece of cake, sir.”

“That’s the spirit. Pick me up at the pub along High Street in fifteen minutes. And mind your lights. Just the pinpoints. There’s a RAF station over the fields.”

Valerie took John’s hand and conducted him across the walk and the roadway. She broke the even rhythm of her progress only to make certain she had negotiated the open gate which gave entrance to the common. Once on the path which cut diagonally across the common to High Street, she resumed a normal pace but she did not let go of John’s hand. The press of his fingers on hers was inexpressibly shy and tender. She felt like weeping although she could think of no urgent reason for it.

She didn’t know him really well. They had met in the military hospital at Watford. It was on a Sunday, sunny and warm and deathly quiet. The defeat at Dunkerque had stunned the people of Britain into a haze of unbelief as if they were all asleep and the dream was unpleasant and one had to walk quietly because it was impolite to disturb a dream no matter how unpleasant.

She had come down to London from the A.T.S. station at Lincoln on compassionate leave along with a score of red-eyed girls in khaki who sought word of the fate of husbands, brothers, and fathers in the British Expeditionary Force. She had waited with the others in a hostel on Sloane Street for six miserable days while the survivors were sorted out in countless ports and beaches on the southeast coast, until that Sunday the War Office called her to say that Brigadier Frederick Hassard Russell was to be found in the military hospital at Watford. She had stood looking down at his unconscious eyes which were the only part of his face and neck uncovered by bandages, and in the welter of frantic visitors in the forty-bed officers’ ward she had scarcely taken note of the haggard young man in filthy battle dress who hovered near the brigadier’s bedside. And then an M.O. had come by, saying, “By the way, Miss Russell, Lieutenant Wynter can tell you what happened. He was there. Matter of fact, he escorted the stretcher all the way from St. Omer until we had your father safely on the operating table.”

She saw him again several weeks later, after her father had returned to “Darjeeling” on convalescent leave. John had arrived to fulfill his last duty as the brigadier’s aide. He spent two concentrated days compiling an official record of the ghastly defeat at St. Omer. It was then that she first noticed the man’s inordinate shyness. He seemed like a schoolboy in the first flush of puberty, unwilling to look directly at her, and when they passed in the narrow hall she had the impression he shrank against the wall to avoid contact by the widest possible margin, a practice which amused her and to some extent engaged a latent protective instinct in her.

During the next twelve months he had showed up several times, whenever his military journeyings brought him remotely into the area, and he seemed quietly content with tea or a meal and the evidences that the brigadier was gradually recovering from his wounds. But in the summer of 1941, when he decided to volunteer for the Commandos, he had asked her to come out for a walk in the fields and it was to her that he haltingly broke the news of his decision.

His subsequent visits became as frequent as the stern regimen of Commando training allowed, and although he spent most of the time chatting with the brigadier about the new daredevil corps which was to spearhead Britain’s return to the offensive, an understanding, unspoken yet vivid, came into being that the purpose of his journeys to Burlingham was to see her. He had family of his own, of course. He was the second of Viscount Haltram’s three sons but he apparently derived scant warmth from a leave spent at Smallhill, the rambling manor house near Tunbridge Wells in Kent. His mother had been dead for years, his older brother Derek was with the Royal Dragoons in the desert, his younger brother Bertie a fighter pilot, and his father was old, introverted and bookish, a dedicated historian, amateur archaeologist, and terribly inept manager of the tax-ridden estate.

As the months passed she came to realize that she had unwittingly penetrated the fabric of his life to a depth she could not fathom, for he spoke very little of himself and not at all of his emotions, and yet she was conscious of an intensity in him her instincts were defenseless to resist. In the Britain of blood and tears, the only softness left to life was a woman’s softness and she was urged to extend it to this gentle, diffident soldier. She often wondered how much of the urge extended to the symbol and how much to the man himself.

Indeed, his very diffidence constantly puzzled her. She had not been surprised to know that he had fought fearlessly at St. Omer, for she had been brought up in military stations and coolheaded bravery was to her a normal attribute of the British soldier. Yet she was completely unprepared to hear that in his first action as a Commando, the raid on Vaagso Island the previous November, he had won his captaincy and an immediate award of the D.S.O. for breaking the hard core of resistance by closing on the two senior German officers and killing them with knife thrusts in the throat. She would not have believed it of this spare, shy man if her father had not read to her, with appetite, the War Office report on the action.

Even now, as they made their way through the gloom of the common, she could scarcely believe it of him. The feel of his hand holding hers was like that of a small boy being led to school.

She said, “I shouldn’t have mentioned the Middle East to Father. You got a ticking off.”

“I don’t mind really. Probably made him feel like old times, ticking me off. He used to do an awful lot of it.”

A few steps later she said, “John, why are they sending only a company?”

“Can’t tell about the War Office. Odd blokes.”

“Will it be raids? Like Vaagso?”

“Something like that, I imagine. Are you sure we’re going the right way? I can’t see a thing.”

She said, “High Street is just ahead. Will you be on the planning staff or—or on operations?”

“We all do a bit of everything.” He chuckled quietly. “You do have the most remarkable eyes, Val—I mean, they give us all sorts of vitamins and eye exercises so we can operate in the dark, and I can’t see anything but absolute pitch. There’s one chap in my company though, Glenning. He can spot a Bren at fifty yards in visibility zero—hallo! What’s this?”

They stopped, puzzled. A faint, diffused light had broken over the common, giving black definition to the buildings ahead on High Street. In almost the same instant the scream of a multi-engined plane, still distant but rising in volume, broke into the silence. They turned about swiftly. A cluster of searchlights had speared the dark across the fields a few miles to the east, moving back and forth, now crisscrossing, now singly, in an urgent, relentless search along the gray-pink underside of a cloud bank.

John said incredulously, “A raid?”

“A fighter-bomber, probably.” She listened intently. “It’s a German, all right. Hear that rhythmic crump?”

“Cheeky of him.”

“They try to shoot up the runway at Belnorton pretty regularly——”

The wail of Burlingham’s siren shattered their ears. It rose and fell in pitch for a long, sickening minute, and when it petered out the sharp rattle of Belnorton’s light ack-ack filled the night sky. Streams of orange tracers leaped up between the shafts of light. The German was climbing and banking and diving. The labor of his motors receded behind the rattle of ack-ack, then came roaring through over it.

“God, Val, it’s wonderfully exciting,” John cried. “What’s this now?”

A new vibration, full-throated and straining with power, convulsed the night air close at hand.

Valerie said, “Our night fighters taking off.” She raised her head as if she could see them and murmured, “God bless them.” She added quickly, “I’ve seen them afternoons in the pub. They’re awfully keen but they’re boys. Children, really.”

Suddenly the roar of motors came down almost upon them, shaking them physically. A furious gust of wind tore at their clothes and drove the rain hard into their faces. They held to each other to keep from being blown off their feet. Then they saw the raider, its exhausts glowing crimson, swoop across a corner of the common like an enormous black hawk. It pulled up gracefully and thundered back into the night sky.

They half ran the rest of the way to High Street. As they reached the cobblestoned thoroughfare, a blinding flash lit the countryside, nakedly revealing for a brief moment the outlines of the village. Then the crack of an explosion rolled across their ears and a fire sprang up in the fields over near Belnorton.

Now the air was filled with the coarse shrieking of many swiftly banking planes and the shattering crack of the big anti-aircraft guns and the incessant chatter of small ack-ack. The searchlights still wildly crisscrossed the sky, revealing nothing in their beams but soft and innocuous gray-pink clouds.

John shouted to make himself heard. “Come on, Val. We’ve only about ten minutes and—well, I’ve got something I want to tell you.”

They hurried over the cobblestones toward a tiny red light which marked the entrance to The Stag at Bay. The street was deserted but here and there among the windows of the old houses a white face could be seen peering upward into the lacerated heavens.

3

A MAKE-BELIEVE firmament on the arched ceiling of the Waldorf’s Starlight Roof twinkled almost as prettily as the summer sky outside and cast a mellow light on a great throng of dancers swaying to the soft rhythm of a song called “I’ll Be Seeing You.”

Uniforms of all ranks and branches abounded. Some couples, encouraged by a battery of alto saxophones, hummed the popular tune as they moved within the narrow restrictions of the overcrowded floor, and the sweet music of farewell invested their faces with an entirely touching sadness.

Jane danced closer to Brad than she would have dared in Malton. She pressed her cheek against the slightly stubbled curve of his jaw, and she enjoyed her awareness of his hard, slim body as if this were a rare and clandestine rendezvous with the man she loved. Brad responded in full measure. His fingers pressed against the nape of her neck, persuading her closer, and the rhythm of his dancing was smooth and exciting.

The saxophones faded out and a cute girl with blond upswept hair slid to the microphone on the bandstand to sing the lyric.

I’ll be seeing you

In all the old familiar places

That this heart of mine embraces

All day through . . .

Jane whispered, “I’m glad we came.”

He said, “The show was good but this is better.”

“I think so too.”

“You never danced like this before.”

She said, “I feel sad and sort of wonderful.”

“Last time I danced this close was at Dartmouth——”

“I don’t want to hear about it.”

“Forgotten her name. Some chorus gal Glen Van Melder brought to a frat dance. Terrific.”

She said, “I’m not interested in your flaming youth.”

He pressed her still closer.

“Didn’t dream I’d marry someone even bitchier.”

“Brad!”

“Had to find out sometime. I’m glad we came.”

“So am I, darling.”

He wanted to remember her this way; her ardor, her decorativeness, the comfort of her. It made the leaving of her harder, and the return greatly to be wished for. Somewhere deep in his mind it compensated for this other urge to leave his set-piece civilization behind him, to plunge headlong into the war. The sweetness of this moment made it somehow easier to go.

The saxophones slid into a new and higher key, and the singer reprised the last eight bars of the song.

. . . I’ll find you in the morning sun

And when the night is new

I’ll be looking at the moon

But I’ll be seeing you.

They glided to a halt and remained a moment locked in each other’s arms.

He whispered, “Will you miss me, Janie?”

She said, “I’ll manage, darling, as long as you miss me—terribly.”

It was a few minutes later that Dan Stenick broke briefly into their last evening.

They were mooning at their table in a remote corner of the crowded room when a roll of drums caught up their attention. The band leader stepped to the microphone. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced, beaming, “as you have read in the papers, six members of the armed forces selected from camps all over the nation are here in New York to inaugurate the war-bond drive. We are proud and happy to have these fine young Americans as our guests tonight——” A ripple of applause rolled across the room. “If the spotlight man will be good enough to pick out table thirty-nine, I’m sure you’ll all want to give them a real big hand!” A spotlight fitfully roamed the room and came to rest on a large table decorated with flags and summer flowers. The six—an ensign, a marine, two army privates, a lieutenant, and a WAC—stood up, blinked, and sheepishly waved their hands. The room thundered with applause and cheers.

Jane touched Brad’s arm. “Isn’t that Lieutenant Stenick? It looks awfully like him.”

Brad had turned his head casually to glance at the party. Now he swung full around.

“I’ll be damned! Dan Stenick——” He chuckled richly. “Wouldn’t you just guess it, darling? About a million first louies around the country and Dan has to snag himself a trip to New York! We’ve got to get him over——” He beckoned a waiter.

Jane said indecisively, “Do you think we should?”

“Of course, Janie! We’ve got to buy him a drink. Imagine running into Dan!” He was chortling as he wrote a note on a table folder.

Of all the junior officers he had served with at Fort Harrison, only Dan Stenick had stimulated him. Dan was old for a lieutenant, thirty-two, stubby and robustly good-looking as a prize fighter (which he was for a time in the depression) might be good-looking, and he possessed a sharp intelligence and disposed so many moods and parts in such surprising profusion that he constantly intrigued all ranks up to the commanding general. Jane didn’t much care for him—for the same reasons (Brad suspected) he found him stimulating. Dan was different from anyone they had ever met. He seemed to revel in having neither background nor breeding. His life had been a patchwork of bizarre jobs, poverty, bursts of prosperity and high adventure, in the course of which he had picked up an amazing amount of knowledge on matters both scholarly and mundane. But (to Brad) nothing about him equaled in importance the wondrous fact that he was a completely free soul. He had no family he ever spoke of, his experience had taught him few scruples, his moods knew no consistency, and his spirit admitted no restraints.

His mood of the moment was clearly evident as he held aloft a whisky glass and dodged between tables toward where they sat.

“As I live and laugh,” he whooped as he came up to their table, “it’s the printer and his doll! H’ya doll!” He grabbed at Brad’s hand and at the same time planted a kiss on Jane’s cheek. “H’ya Brad! What the hell you doin’ here? I figured you over with the Limeys helpin’ Whoosenhauer or Ossenpoofer or whatever his name run our show—and here you are livin’ it up——”

Brad held up a protesting hand.

“Whoa, boy—hold it! Don’t go throwing questions at me. You’re the witness on the stand. How’s C platoon? They hit the LZ on the last jump?”

Dan shook his head soberly. “Bellenger’s got your platoon, Brad. Okay, good boy and all that, but he isn’t you, tootsie. Your boys are pinin’—hell with it. Let’s do a little drinkin’.” He drained his glass and before he had put it down he was wildly snapping his fingers for a waiter.

Brad said, “I figure out of three-four million defenders of our country you belong down around the last half dozen. How come you rate this trip?”

Dan rolled his eyes conspiratorially and brought them to rest on Jane. He said, “Confidentially, your printer husband is eminently correct. I wouldn’t have made corporal in Coxey’s army but——” He muttered to Brad in a mock whisper, “If you’ll buy me a drink, I’ll let you in on the secret. Cheap at half the price. Scotch.”

When the waiter came, Jane held her hand over her glass. Brad ordered drinks for himself and Dan.

“It’s a long story,” Dan said, “but I’ll give it to you in one pregnant sentence. I heard about the Treasury organizin’ this junket and figured I could use six pretty days in New York, all expenses paid, models provided and no holds barred for a hero, so I sat down and wrote my congressman. Get it?”

Brad said, “No, I don’t get it.”

Dan frowned. “Say doll, the printer isn’t very bright tonight. You been wearin’ him down since he got sprung from the outfit?” Jane shuddered but managed a cursory smile. She loathed being called “doll” and his oblique reference to her private life with Brad was akin to Japanese torture which she accepted as part of her war sacrifice. Brad had long since become hardened to the consequences of having a wife as decorative as Jane living with him on a military post.

“It’s this way,” Dan went on, swinging around to Brad. “My congressman’s a real combination—native intelligence of Barney Baruch and moral fiber of Al Capone. He’s got bodies buried everywhere. What’s more important, he knows that I know, so what’s a little thing like callin’ up some joker in the Treasury and droppin’ a little word in favor of a hero, name of Dan Stenick? Now you get it?”

The drinks had come. Brad lifted his and said, “No question about it, Danny boy. Someday you’re going to make a great politician.”

“And to you, kiddo. Turns out you didn’t do so bad yourself.”

“Me? What do you mean?”

“What the hell. Let’s do a little drinkin’.” He waved his glass. “Happy landings!”

“What do you mean, Dan?”

Dan hesitated. Then he sang out, “Okay, but the doll will have to excuse us.” He cupped his hand around Brad’s ear and whispered swiftly, “We’re droppin’, brother. Next month. The real thing. Don’t know where yet but I figure the Aleutians. Place called Adak. Now for Christ’s sake, forget it.” He turned to Jane. “Okay, doll. Everythin’s fixed. Let’s start livin’ it up again. Dance, sweetheart?”

She said, “Sorry, Dan. I’ve only got a dance or two left in me and this is Brad’s last night.” She glanced anxiously at her husband. The cleft in his chin made a deep furrow. She knew the symptom.

Dan knew it too. He swallowed his drink in big gulps, bit his lips, essayed a smile, then fell into a long silence. Suddenly he got up.

“I been thinkin’, Brad. They know what they’re doin’ down in Washington. They’re no fools. You were the best in the outfit. Real class. They need guys like you where it counts most. That’s why they reassigned you. Me? Give me two and two and I’ll come up with three and a half. Not ’cause I don’t know better, ’cause I always got to figure my percentage. Any mug can jump. That’s why the big brass reached out and grabbed you for the London job. I wanted you to know because I love you, tootsie. You don’t mind, do you, doll? G’by and God keep you. Real good.”

He ruffled Brad’s hair and, giving him no time to reply, pranced away.

Brad watched him until he was lost behind some couples coming off the dance floor.

Jane said, “Was it important?”

He wished he could tell her about his old outfit going into action. She would be more content about his reassignment to London.

He said, “There’s no telling. He was drunk.”

“You were angry for a minute.”

“No one on earth can stay angry with Dan for more than a minute. He’s quite a guy.”

She pressed across the corner of the table that separated them.

“I’m finding out you’re quite a guy too, darling.”

They finished their drinks slowly, oblivious of the festive air and the music and goings and comings of people around them. They knew the time had come to go down to their room. He signed the bill and they walked hand in hand to the elevator.

The moon over East Forty-ninth Street played around their wide-open window and cut sharply into the darkened room. Somewhere, probably still on the roof, the music of a dance band was faintly heard in counterpoint to honks of taxicab horns in the street far below.

She lay in the curve of his arm. Idly they watched the curtains billowing before a light warm breeze that penetrated the room and refreshed their bodies.

After a time she said drowsily, “Darling——”

“Yes.”

“Little confession——” She hesitated. “When I saw Sanford Jaques at the luncheon I thought you’d arranged something.”

“Arranged what?”

“And when you got so angry with Dan Stenick I thought about it again.”

“Arranged what, Janie?”

“For you to get a transfer overseas instead of staying at Fort Harrison.”

He thought, ‘She must have a lot of old Everett Bolding in her. Never loses sight of her point. Not Janie—lovely, soft Janie. She had to chase down every doubt, and know, and be reassured.’

She said, “Wasn’t it awful of me?”

“Terrible.”

“But he didn’t have anything to do with your reassignment, did he?”