Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

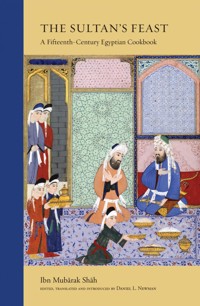

The Arabic culinary tradition burst onto the scene in the middle of the tenth century when al-Warraq compiled The Book of Dishes, a culinary treatise containing over 600 recipes. It would take another three and half centuries for cookery books to be produced in the European continent. Until then, gastronomic writing remained the sole preserve of the Arab-Muslim world, with cooking manuals and recipe books being written across the region, from Baghdad in the East to Muslim Spain in the West. A total of nine complete cookery books have survived from this time, containing nearly three thousand recipes. First published in the fifteenth century, The Sultan's Feast by the Egyptian Ibn Mubarak Shah features more than 330 recipes, from bread-making and savoury stews, to sweets, pickling and aromatics, as well as tips on a range of topics. This culinary treatise reveals the history of gastronomy in Arab culture.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 559

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE SULTAN’S FEAST

THE SULTAN’S FEAST

A Fifteenth-Century Egyptian Cookbook

Ibn Mubārak Shāh

Edited, Translated and Introduced byDaniel L. Newman

To Nayla

SAQI BOOKS

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Published 2020 by Saqi Books

Copyright © Daniel L. Newman 2020

Daniel L. Newman has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

ISBN 978 0 86356 156 6

eISBN 978 0 86356 181 8

CONTENTS

Preface

Note on Transliteration

Introduction

The Mediaeval Arabic Culinary Tradition

The Text

THE BOOK OF FLOWERS IN THE GARDEN OF ELEGANT FOODS

1. Useful Things That a Cook Should Know

2. Bread Making

3. On Drinking Water

4. On Dishes

5. On Making Murrī

6. On Making Omelettes and Other Things

7. On Counterfeit Dishes

8. Fish

9. Sweets

10. On Beverages like Fuqqāʿ and Sūbiyya

11. On Making Mustard

12. Sauces

13. On Dairy Dishes

14. On Pickles

15. On Storing Fruits and Keeping Them When They Are Out of Season

16. Dishes

17. On Making Cold Dishes

18. On Toothpicks

19. On Fragrances

References

English Index

Arabic Text

Arabic Index

PREFACE

WHEN, AS A STUDENT, I was making my first inroads into the wonderful world of the Middle East, I remember being struck by the uncanny similarity between one of the Babylonian words for ‘doctor’, āshipu, and the Persian word for ‘cook’, āshpaz. What made this even more interesting was the fact that the āshipu was actually a witch doctor, who employed magic in order to remedy the ills that bedevilled his patients. Later on, I found another tempting culinary cognate, ashbū, which, so my trusted dictionary told me, meant ‘chafing-dish’, or perhaps something closer to a magician’s cauldron. What magic is this, I wondered? Were Babylonian cooks so skilled that, over time, they came to be known as magical doctors (of food), with the word travelling eastward to Persia, possibly along with some chafing dishes? The etymological conundrum became more interesting with the addition of another ingredient: the ancient Greek mágeiros, a relative of the word for magus (mágos), which at various points throughout history denoted butcher (originally of sacrificial animals), priest and cook (as it still does today).

The link between food, or rather the creation thereof, and magic seemed obvious to me, even then. It has never ceased to be so, particularly since I have gained theoretical knowledge and practical experience over the course of extensive travelling, and have delighted in the magic of seemingly random ingredients being transmogrified into succulent blends that are always much more than the sum of their constituent parts.

This book combines a number of my passions, as it is about language (Arabic, in particular), history, culture and food. It is a journey of pleasure through time, to the fifteenth century, to partake of the culinary joys from a distant past.

Food is, of course, much more than the act of eating, or a knowledge of ingredients. It is difficult to imagine anything more profoundly cultural and social than food, and it is often the first experience many of us have with the ‘Other’, in the broadest possible sense of the term.

Courtesy of our increasingly globalized world, what was once strange, exotic and even a little fearful, has now become an integral part of our daily lives. Nowhere more than in food does the diversity of our modern-day societies manifest itself on a daily basis. It is through food that relations and friendships are forged – over the breaking of bread, as the saying goes.

The study of food does not merely give us recipes, but also brings to light the interactions between peoples and changes in society, which, like cuisines, are enriched by extraneous additions that, just like ingredients, are mixed together to produce something exciting and new. When human beings travel, they do not take only their passports and belongings with them, but also memories of their native lands, of which culinary traditions are a major component. Food is a quintessential element in what Fernand Braudel called ‘the repeated movements, the silent half-forgotten story of men and enduring realities, which were immensely important but made so little noise.’1 It is these ‘silent’ stories that tend to speak the loudest.

A bite into a Turkish and Central Asian manti and börek, a Balkan burek, East European pirogi, Russian pelmeni, Greek boureki, Georgian khinkali, Indian samosa, Somali sambuus, or a Cornish pasty is to join a fascinating gustatory journey, which had its origins in a Chinese jiaozi (dumpling). All of these dishes consist of a (usually savoury) dough or pastry filled with meat and/or vegetables and spices. Their common precursor, and main conduit into cuisines across several continents, is the mediaeval Arab sanbūsaj (or sanbūsak) which started life in Baghdad, from where it travelled throughout the expanding Islamic empire, and beyond.

This book presents both a critical edition and translation of the last known mediaeval Arabic culinary text, entitled Zahr al-ḥadīqa fi ’l-aṭcima al-anīqa (Flowers in the Garden of Elegant Foods), and will bring alive the smells and flavours of Mamluk Cairo, just a couple of decades before the region fell to the Ottomans.

On my journey, I have been fortunate to receive help when I needed it most, and I am pleased to be able to thank staff at the library of the University of Leiden (Netherlands), the British Library (London), the National Library of Medicine (Bethesda, MD), the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library (Yale University), the UCLA Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, the National Library of Tunisia (Tunis), and the Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris) for greatly facilitating my researches and their assistance in accessing the required manuscript sources. A special word of thanks is due to Ms Judith Walton and my friend Dr Mamtimyn Sunuodula at Durham University’s Bill Bryson Library for their unstinting efforts to accommodate my often-complicated requests.

I should also like to express my gratitude to Durham University for granting me research leave, during which I was able to conduct part of the research that ultimately found its way into the book.

I benefited from the stimulating exchanges with those working in the same field, particularly in the context of papers delivered at the International Conventions on Food History and Food Studies, organised by the European Institute for Food History and Cultures (IEHCA) at the University of Tours.

And finally, as ever, this work would not have been possible without the unflagging support of Whitney Stanton, my most trusted and beloved companion on this journey – as on all others – who ensured that the authorial endeavour was accompanied by dishes recreated from the manuscript, and shared her vast culinary knowledge, which often provided invaluable insights.

____________________

1 1974: 15.

NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

THE TRANSLITERATION USED in the book is a ‘narrow’ scholarly one, with some minor amendments: initial hamza is not transliterated, no distinction is made between alif mamdūda and alif maqṣūra, both of which are rendered as ā. The tāʾ marbūṭa marker is not rendered, except when it occurs as the first element in a status constructus (the so-called iḍāfa).

INTRODUCTION

The Mediaeval Arabic Culinary Tradition

Until relatively recently, Arabic culinary history enjoyed very little attention, and was the object of only a few studies.1 This is all the more remarkable since it is the richest in the world in terms of the extant resources, which predate the earliest European recipe collections by several centuries. As one observer put it, ‘from the tenth through the thirteenth centuries, Arabic speakers were, so far as we know, the only people in the world who were writing cookbooks.’2 Even if in the meantime, the discovery of a collection of twelfth-century Latin recipes produced at Durham Cathedral Priory3 vitiates part of this claim, it does not detract from the extraordinary history of the Arabic tradition, not least because of the sheer number of recipes, which number in the thousands.

The rise of this rich culinary tradition occurred during the Abbasid caliphate (750–1258 CE) and is thus another product of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of Islam. The esteem in which the culinary art was held in the early Abbasid empire was such that among the authors of cook books we find several caliphs – Ibrāhīm al-Mahdī (d. 839 CE), al-Ma’mūn (d. 833 CE) and al-Wāthiq (d. 847 CE) – as well as famous scholars from various fields and disciplines. One culinary author provided his own explanation for the reason rulers, grandees and scholars started writing cookery books. Some chefs, he claimed, do not care about their work and are only interested in getting things done as quickly as possible and leaving the kitchen. Furthermore, they take little care and few precautions, which is why everything has to be explained to them and they need to be supervised: ‘it is these flaws which have led caliphs and rulers to do the cooking themselves, to create dishes and compose many books on the subject.’4 Cookery books were collected by the high and mighty. The owner of the earliest copy of the oldest work was the Ayyubid ruler of Damascus and Egypt, Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb (d. 1249 CE).5 The culinary appreciation of these recipe books amongst the wealthy continued well past the Abbasid caliphate into the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan himself commissioned an ornate copy of al-Baghdādī’s cookery book, complete with magnificent gold-leaf headings.6 A Turkish translation was made of the same book in the 15th century, by a certain Maḥmūd Shirvānī (Mehmed Chirvani), who added over ninety recipes of his own, thus producing the first Ottoman cookery book.7

10th century

Author

Recipes

1.

Kitāb al-ṭabīkh [wa ‘l-’iṣlāḥ al-aghdiyya al-ma’kulāt wa ṭayyib al-aṭʿima al-maṣnūʿāt]a(A Cookery Book with the Best Food and Finest Preparations)

Abū Muḥammad al-Muẓaffar Ibn Naṣr Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq [Baghdad]

615

13th century

2.

Kitāb al-ṭabīkhb(Cookery Book)

Muḥammad Ibn al-Ḥasan Ibn Muḥammad Ibn Karīm al-Kātib al-Baghdādī (d. 637 AH/1239–40 CE) [Baghdad]

161

3.

al-Wuṣla ilā ‘l-ḥabīb fī Waṣf al-ṭayyibāt wa ‘l-ṭībd(Reaching the Beloved through the Description of Delicious Foods and Flavourings)

anon.c [Aleppo]

635

4.

Kitāb al-ṭabīkhe

anon. [al-Andalus]

472f

5.

Fuḍālat al-khiwān fī ṭayyibāt al-ṭaʿām wa ‘l-alwāng(Delicacies of the Table as regards the Finest Foods and Dishes)

Abū ‘l-Ḥasan ʿAlī Ibn Muḥammad Ibn Razīn al Tujībī [al-Andalus, Tunisia]

428

6.

Kanz al-Fawā’id fī tanwīʿ al-Mawā’idi(Treasure of Benefits in the Variety of Dishes)

anon. [Egypt]

750/79h

7.

Taṣānīf al-aṭʿima (Classification of Foods)j

anon.

171

14th century

8.

Kitāb Waṣf al-aṭʿima al-muʿtādak(The Book of the Description of Familiar Foods)

anon. [Egypt]

480

15th century

9.

Kitāb al-ṭibākhal

Jamāl al-Dīn Yūsuf Ibn Ḥasan Ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī al-Ṣāliḥī, Ibn Mubarrad (Mibrad) (1437–1503) [Damascus]

55m

10.

Zahr al-ḥadīqa fi ‘l-aṭʿima al-anīqa (The Flowery Garden of Elegant Food)n

Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad Ibn Mubārak Shāh (1403–1458) [Egypt]

332

TOTAL

4,178

____________________

a The text has survived in three copies: Oxford, Bodleian, Huntington 187; Helsinki University Library, MS Coll. 504.14 (MS Arab 27); and Istanbul, Topkapi Saray, Ahmed III Library, 7322 A. 2143 (dated 696 AH/1297 CE). It was the second treatise (after al-Baghdādī’s) to be published (Öhrnberg & Mroueh, 1987). It was also the subject of a second edition, by Iḥsān Dannūn al-Shāmīrī, Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh al-Qadaḥāt & Ibrāhīm Shabbūḥ (Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh wa Iṣlāḥ aghdhiyyāt al-ma’kūlāt wa ṭayyib al-aṭʿima al-maṣnūʿāt, Beirut: Dār Ṣādir li ‘l- Ṭibāʿa wa ‘l-Nashr, 2012). The only complete translation is that by Nasrallah 2007. Translated extracts can be found in Waines 1989 (French trans., Marie-Hélène Sabard, La Cuisine des califes, Arles: Sindbad/Editions Actes Sud, 1998); Zaouali 2007 [twenty-four recipes]; Salloum et al. 2013.

b In addition to the autograph manuscript (Istanbul, Süleymaniye, MS Ayasofya 3710, dated 623 AH/1226 CE), there is only one other known (undated) mss copy (British Library MS Or5099). The text has been edited several times, by Dāwūd al-Jalabī (Kitāb al-ṭabīkh, Mosul: Maṭbaʿat Umm al-Rabīʿayn, 1934), Fakhrī al-Bārūdī (Kitāb al-ṭabīkh wa dhayl ʿalayhi al-ma’ākil al-Dimashqiyya, Damascus: Dār al-Kitāb al-Jadīd, 1964), and Qāsim al-Sāmarrā’ī (Kitāb al ṭabīkh, Beirut: Dār al-Warrāq li ‘l-Nashr, 2014). All of the editions rely solely on the Istanbul autograph. It has been translated into English several times (Arberry 1939; Perry, in Rodinson et al. 2001: 19–90; Perry 2005), and in Italian (Mario Casari, Il cuoco di Bagdad. Un antichissimo ricettario arabo, Milan: Guido Tommasi Editore, 2004). Some of its recipes are extracted in Waines 1989; Salloum et al. 2013; Saʿd al-Dīn 1984.

c The text was clearly a bestseller as it has survived in no fewer than fifteen mss copies, the oldest of which dates back to the early fourteenth century, though not all of them are complete: Aleppo, Aḥmadiyya (later Waqfiyya) library, No. 1678; London, British Library, Or6388; London, School of Oriental and African Studies Library, ms. 90913; Oxford, Bodleian, MS. Huntington 339; Damascus, Ẓāhiriyya library, Adab 3259; Istanbul, Topkapi Saray, Ahmed III library, 157 2088 [dated 30 October 1330]; Cairo, Dār al-Kutub, Taymūr 75; idem, Ṣināʿa 74 (703 AH/1303–4 CE); idem, Lām 5076; Istanbul, Süleymaniya library, MS Fatih 3717 (dated Rabīʿ II, 873 AH/October 1468 CE); Paris, BNF, Arabe 4938 [dated Rabīʿ II 1126 AH/April 1714 CE]; Berlin, Staatsbibliothek WE 5463 [extract]); Patna, Bankipore Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library, 2193: 259/1; idem, 96/4; Bursa, Inebey medresi. Another known manuscript (dated 979 AH/1571–2 CE), held in Mosul (Madrasat al-Ḥājjīyāt), appears to have been lost (see Wuṣla 1986, II: 334). The text was first edited by Sulaymān Maḥjūb and Durriyat al-Khaṭīb (Aleppo: Maʿhad al-Turāth al-ʿIlmī al-ʿArabī, 2 vols, 1986), and then with accompanying English translation by Charles Perry (2017). References will be to the latter edition (hereinafter referred to as Wuṣla). For a discussion of the manuscripts, see Wuṣla 1986: II, 415–447 and Wuṣla 2017: xxxix–xl.

d The editors of the 1986 edition attributed the text to Kamāl al-Dīn ʿUmar Ibn Aḥmad Ibn al-ʿAdīm (1192–1262). However, since then the authorship has been called into question; for a discussion, see Wuṣla, xxxvii–viii.

e Until recently, this cookbook was thought to have survived in only one manuscript (BNF Ar7009), which was completed on 13 Ramaḍān 1012 AH/14 February 1604 CE. It was first edited by A. Huici Miranda, ‘Kitab al tabij fi-l-Magrib wa-l-Andalus fi ‘asr al-Muwahhidin, li-mu’allif mayhul (Un libro anónimo de la Cocina hispano-magribí, de la época almohade)’, Revista del Instituto de estudios islámicos, IX/X (1961–62) 15–256 [= La cocina hispano-magrebí en la época almohade según un manuscrito anónimo. Edición crítica. Madrid: Impr. del Instituto de estudios islámicos 1965]. Catherine Guillaumond’s unpublished PhD dissertation, La cuisine dans l’occident arabe médiévale (Université Jean Moulin-Lyon III de Lyon, 1991) included a critical revised edition, as well as a French translation. In the early 2000s, the Moroccan scholar ʿAbd al-Ghanī Abū ‘l-ʿAzm discovered another copy of the same text (477 recipes), completed on 18 Dhū’ l-Qaʿda 1272 AH/21 July 1856 CE and entitled Anwāʿ al-ṣaydala fī alwān al-aṭʿima (‘Pharmaceuticals in Food dishes’), which he edited and published in 2003 (Rabat: Markaz Dirāsāt al-Andalus wa-Ḥiwār al-Ḥaḍārāt bi ‘l-Ribāṭ [repr. 2010, Rabat: Mu’assasat al-Ghanī li ‘l-Nashr]). The BnF mss was first translated by A. Huici Miranda (Traducción española de un manuscrito anónimo del siglo XIII sobre la cocina hispano-magribi, Madrid: Maestre, 1966; 2nd ed. La cocina, hispano-magrebí durante la época almohade, 2005, Madrid: Trea). Charles Perry translated it into English under the title An Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook of the 13th Century, but to date it has only appeared on line (http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Medieval/Cookbooks/Andalusian/Andalusian_contents.htm) [519 recipes], with a revised (and augmented) version being made available by Candida Martinelli et al. (http://italophiles.com/al_andalus.htm). Guillaumond published a French translation: Cuisine et dietetique dans l’occident arabe medieval d’après un traité anonyme du XIIIe siècle. Étude et traduction française, Paris: L’Harmattan, 2017. The text will be referred to hereinafter as Andalusian, with references to the Arabic text being to the BNF manuscript, whereas Abū ‘l-ʿAzm’s edition will be referred to as Anwāʿ.

f This number excludes the descriptive entries on herbs and spices, as well as the appended list of fifty-seven medicinal syrups and electuaries (fols. 76–83).

g In addition to mss copies in the Royal Academy in Madrid (Galuengos 16) and Tübingen University (Ar. 5473), there is also one held in a private collection. It was first studied by Fernando de La Granja y Santamaria (La cocina arábigo-andalusa según un manuscrito inédito, unpubl. PhD diss., Madrid, 1960). The edited text by Muḥammad Ibn Shaqrūn and Iḥsān ʿAbbās (Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 1984, repr. 2012) relied on all three manuscripts, whereas Ibn Shaqrūn’s earlier edition (Rabat, 1981) was based only on the privately held one. The present author has identified another manuscript copy of al-Tujībī’s text in a British Library manuscript collection of several medical treatises (Or5927, fols. 101r.–204v.). Unfortunately, none of the extant versions are complete as there are eight chapters missing (six from the seventh section, and two from the tenth). There are two complete translations, one in Spanish (Manuela Marín, Relieves de las mesas, acerca de las delicias de la comida y los diferentes platos, Madrid: Trea, 2007), and one in French (Mohamed Mezzine & Leila Benkirane: Fudalat al-Khiwan d’ibn Razin Tujibi, Fez: Publications Association Fès Saïss, 1997), with extracts (fifty-three recipes) appearing in Zaouali 2007. Also see Ibn Sharīfa 1982; Heine 1989.

h It has survived in six manuscripts: Dublin, Chester Beatty Library No. 4018; London, Wellcome Library WMS Arabic 260; Cambridge University Library, No. 192; Cairo, Dār al-Kutub, Ṣināʿa 18; Gotha Orient A 1345 (Arab 117); Patna, Bankipore Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, No 2. The sole critical edition is by Manuela Marín and David Waines (Beirut/Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1993), with an English translation by Nawal Nasrallah, Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table: A Fourteenth-century Egyptian Cookbook, Leiden: Brill, 2018 (unfortunately, I was not able to access this work during the preparation of the present book). Zaouali 2007 also includes thirty-seven recipes from the book. It will be referred to hereinafter as Kanz. All the references in the text are to the Marín and Waines’ edition.

i The second number refers to recipes placed in the Appendix of the published edition, since they were not found in the Cambridge manuscript the editors used as their basic text, but only in the Chester Beatty or Cairo manuscripts. Most of them are from the latter, with four occurring in both the Chester Beatty and Cairo mss. (Nos. 37, 38, 40, 46) and four only in Chester Beatty (Nos. 42, 43, 44, 45).

j Wellcome, WMS Arabic 57, Fols. 48r-112v. It does not appear to have been identified as a culinary treatise, and is part of a collection that also includes a treatise on simple medicines (al-adwiya al-mufrada) by the Andalusian polymath Abū ‘l-Salt (1068–1134), who was not, however, the author of the cookbook. The origin of the text is unknown, as is the date. The only factual clue as to the origin of the manuscript copy is that it was written in the Maghribi script. It has speculatively been placed in the 13th century since the types of recipes are closer to those found in other treatises of the period. Secondly, there are similarities with the work of the eleventh-century pharmacologist Ibn Jazla (see below), and recipes found in al-Baghdādī and Waṣf. This would support the hypothesis that the manuscript was copied in the Muslim West, but produced in the East. The present author is preparing a study and edition of the work where these issues will be further elaborated.

k There are only two extant manuscript copies, both held in Istanbul (Topkapi Saray Library, 62 Ṭibb 1992 and Ṭibb 22/74, 2004 (dated 13 Jumādā II 775 AH/30 November 1373 CE), copies of which can also be found in Cairo, Dār al-Kutub (Ṣināʿa 51 and Ṣināʿa 52, respectively). An English translation was made by C. Perry, ‘The Description of Familiar Foods’, in Rodinson et al. 2002: 273-466 (hereinafter referred to as Waṣf).

l It was edited by Ḥabīb al-Zayyāt (al-Mashriq, vol. 35, 1937, pp. 370–376), with an English translation by C. Perry, ‘Kitāb al-ṭibākha: A Fifteenth-century Cookbook’, in Rodinson et al., 2000, pp. 467–76 (= Petits Propos culinaires, 21, pp. 17:22). For details on Ibn Mubarrad, see Richardson 2012: 97–104.

m This number takes into account variants in individual entries (= 44) in the edition.

n Henceforth referred to as Zahr.

The table above lists the ten cookery manuals that are known to have survived. They span a period of five centuries (tenth to fifteenth) and represent a geographical area extending from al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) to Tunisia, Egypt, Baghdad and Aleppo. Another forty or so are known by their titles only.8

The history of the Arab culinary tradition is wrapped in mystery. The first is that, based on current evidence, it burst onto the scene fully formed, without any apparent evidence of gestation stages. That is, if we accept the consensus view that the treatise considered the oldest actually deserves this epithet, despite the fact its oldest dated manuscript is from the late 13th century (1297 CE) – over seventy years after al-Baghdādī’s autograph (the only one among the texts) from 1226 CE. Combined with a relatively small number of works across half a millennium, this complicates attempts at identifying trends and periodization.

The issue of authorship – or, to be more precise ‘ownership’ – of the recipes is a highly challenging question. For a start, at least half of the treatises have no, or dubious, authorship, whereas in many – if not all – cases, it is unlikely that one is dealing with a wholly self-contained collection, but rather, for the most part, a sample from a historical pool of recipes.

According to Maxime Rodinson, the author of the first study of Arabic culinary writings,9 by the end of the Abbasid Empire, the books had ceased ‘to be a princely amusement, a distraction for the highborn courtier, earning him a reputation for good taste and fine manners’, and became the preserve of ‘obscure scholars, part-time epicures who wish to preserve for themselves recipes of dishes they have enjoyed so that they can have their servants prepare them on demand. In short, they are simple recipe notebooks for home use, like the part devoted to cookery in the Menagier de Paris.10 Such books are not often copied, but the successive owners of each manuscript tend to add further recipes in the margins thus increasing their utility.’11

Unfortunately, the reference to a ‘golden age’ in culinary writing is based solely on references to works that have not survived, whereas the description of the ‘post-classical’ group – thirteenth century onwards – is somewhat oversimplified in light of the extant manuals.

In terms of genres, it is possible to divide the corpus into two broad categories: works that consist solely of recipes, and those that have literary aspirations and include poetry, as well as dietetic information. The latter group may conveniently be considered a type of adab literature, which refers to works of savoir-vivre produced for the cultured elite and contained a collection of prose, poetry and anecdotes. Al-Warrāq’s book exemplifies this genre, with its numerous poems, the frequent use of a high-literary register, complete with rhymed prose (sajʿ) in titles, and attention to dining etiquette, not found in any of the other works. However, one single treatise does not a genre make, and in the absence of any other, it is not possible to extrapolate its features to works of which we only know the title.

The second biggest group consists of recipe collections, which may, however, contain some dietetic elements, as well as medical preparations, but whose features do not comply with high literary conventions of the time. The fact that these were intended for use by people who knew their way around a kitchen – or used it to instruct their servants (as in the case of Zahr) – explains why recipes generally provide little detail on quantities and exact preparation methods and timing. Similarly, the fact that, like today, they would have been used in a kitchen environment, which is not conducive to the preservation of paper, explains the relative dearth of surviving copies.

Geographically, we can divide the existing books into two categories, those produced in the Near East, and those from the Muslim West, i.e. al-Andalus and North Africa.

One thing all treatises, except Ibn Mubarrad’s, have in common is that they for the most part reflect a cuisine enjoyed by gatherings of the elite. This is evident from the technical complexity of the dishes, the equipment required, and the preciousness of some of the ingredients. Equally significant is the fact that the books were produced in the centres of power and culture of the time (Damascus, Aleppo, Cairo, Tunis), where potential patrons could be found. One should be wary, therefore, of using the books as a mirror of mediaeval Arab societies, since, for the most part, they say very little about the daily lives of the vast majority of the population.

What is known about the authors, and why and how did they write the books? They include a bookseller (al-Warrāq), a government scribe (al-Baghdādī), a religious scholar (Ibn Mubarrad), a poet (Ibn Mubārak Shāh), and a government official (al-Tujībī). The motive for writing is rarely made explicit. Exceptions include al-Baghdādī, who states he composed the book for himself ‘and whomever may want to use it in the making of dishes’,12 whereas the author of Wuṣla invoked religious motives as ‘consuming good foods strengthens adoration in God’s servants and draws pure praise from their hearts.’13

There is no direct evidence that any of the authors was a professional cook, and in some cases their experience may have been limited to eating the dishes. However, some went well beyond that, and the author of Wuṣla proudly stated: ‘I have included nothing without having tested it repeatedly, eaten it copiously, having worked the recipe out for myself, and tasted and touched it personally.’14 As a result, the comment by Perry15 that ‘it is clear that scribes were uniformly ignorant of cooking,’ and that ‘[a]s a result, cookery manuscripts tend to be marred by a remarkable number of errors’ is somewhat tenuous.

An obvious corollary of the above is that it is more accurate to talk of compilers rather than authors. Their sources no doubt included professional cooks’ recipe collections, as well as other compilations. Al-Warrāq, for instance, mentions a large number of authors – twenty in total – whose works he consulted and who included physicians, dignitaries and caliphs, like the afore-mentioned gastronome Ibrāhīm Ibn al-Mahdī. It is relatively rare to find references to specific works. Exceptions include the anonymous Andalusian, whose author mentioned one of the other extant treatises (al-Baghdādī’s),16 as well as Ibrāhīm Ibn al-Mahdī’s Kitāb al-Ṭabkh17 and even a solitary Persian source.18

Slightly less rare are the attributions – often putative – to individuals who allegedly invented the dish (which may be named after them), or even taught it to the author. For instance, in Wuṣla there are references to a cake made by a maidservant (jāriyya) of al-Malik al-cĀdil al-Kabīr,19 ‘an elegant and extraordinary gourd recipe [learned] from the daughter of the governor of Mārdīn,’20 and one ‘learned from the domestic servants of al-Malik al-Kāmil.’21 Probably the most famous example is that of the Būrāniyya, named after Būrān, the caliph al-Ma’mūn’s wife, who, according to tradition, was an accomplished cook, renowned for her fried aubergine dishes. References to chefs are rare and they, like most craftsmen in history, generally remain anonymous.22 Whilst the kitchens in the grand households would also have included women, the authors of cookery books are all men.

Turning briefly to the organisation and content of the cookery books, it is possible to identify a number of common features. With the exception of Ibn Mubarrad’s manual, where recipes are organized in alphabetical order, the other treatises tend to group dishes together in chapters, according to cooking methods (fried, oven dishes) and/or main ingredient (e.g. fish, chicken), flavours (sweet, sour), or the type of dish (vegetarian, condiments, pickles, beverages, sweets, cold dishes). Some, like Wuṣla, have an overarching structure in that they broadly follow the various stages of the banquet.

The modern concepts of breakfast, lunch and dinner did not exist, and the cookery manuals provide no details about such divisions, or when dining should occur. In fact, there is little information anywhere about this aspect. One of the few sources to address this was the fifteenth-century author al-Aqfashī, who stated that ‘for the Muslim the time of lunch (ghadāʾ) began at dawn and lasted until midday. Afterwards the time of supper (ʿashāʾ) started, which lasted until midnight.’23 This may be compared to practice in the early nineteenth century in Egypt, where supper was always the principal meal and it was ‘the general custom to cook in the afternoon; and what remains of the supper is eaten the next day for dinner, if there are no guests in the house. Evening meal is before the evening prayer.’24

While Ibn Mubarrad’s collection is the only one that provided recipes of everyday food, some of the others occasionally included recipes that were inspired, and enjoyed, by the common folk.25 The Andalusian, for instance, includes two dishes eaten by ‘shepherds in the countryside of Cordoba’, a ‘servant’s recipe’, as well as several for slaves,26 whereas al-Tujībī’s choice of ingredients (e.g. tripe) and references to food being cooked in the communal oven also reflect a less high-brow cuisine.

Even a cursory examination of the manuals yields a number of overlaps, between, on the one hand, the Near Eastern works (excluding Ibn Mubarrad), and those from North Africa and al-Andalus. In addition to overlaps between Kanz and Wuṣla (e.g. mains,27 desserts,28 condiments,29 hygiene compounds,30 incense31 and perfumes32), there are similarities between al-Warrāq, al-Baghdādī and Kanz. In some cases, the relationship is much more direct, as in Kanz/Zahr and al-Baghdādī/Waṣf. The varying degrees of relationship or influence (sometimes just a couple of recipes) may be tentatively represented in the chart on the facing page.

The state of present research – not least in terms of dating and authorship – makes it very difficult to trace the direction of the borrowing and, indeed, of the sources. If anything, the gaps in the current knowledge support the hypothesis of other ‘donors’ that have since then been lost. The fact that multiple recipes have identical names, even within one and the same cookery book, but diverge in terms of ingredients and/or instructions, also lends support to the idea that recipes were gleaned from different sources.

In line with the occasions at which they were served, the dishes were intended to impress at every level and appeal to all the senses by presentation, ingredients, smell or colour.33 Meat reigned supreme. Although some of the cookery books contained vegetarian dishes, these were often deemed fit only for sick people and Christians during Lent. Probably the most grotesquely carnivorous recipe is one allegedly made for the Governor of Ceuta (Morocco), and involves an oven-roasted lamb that has been gutted and then filled with a sparrow inside a starling inside a pigeon inside a chicken inside a goose.34 Clearly not a dish for a household oven.

Like meat, sweets were associated with ‘the upper classes [and] were identified with the food of kings.’35 However, the most valuable commodity in the dishes were rare and exotic ingredients (especially spices), and so the culinary writings reveal a great deal about international trade at the time, too.

From within the Muslim empire, there came yoghurt, dates, leeks, pomegranates, rice and roses from Persia; quince and apples from Isfahan; fruit syrup from Shiraz; pears from Sijistan; grapes, rhubarb, raisins and sumac from Khorasan; saffron and olive oil from North Africa; melons from Samarqand; leek and mulberries from Syria; and agarwood from Socotra. Many ingredients were sourced from farther afield, as well, and the author of the oldest extant geographical manual, Ibn Khurradādhbih (d. 912 CE), described the activity of Arab merchants who returned from China with silk, musk, agarwood, coconuts, cassia, cinnamon, galangal, sandalwood, agarwood, camphor, cloves and nutmeg.36 In the case of cassia, its Arabic name, dār ṣīnī, reveals both its origins and journey, as it goes back to the Persian dār chīnī, meaning ‘Chinese wood, or bark’.

Very early on, the spice trade was firmly in Arab-Muslim hands, and the ninth-century Akhbār al-Ṣīn wa ’l-Hind (‘News from China and India’) informs us that there was already a Muslim community in Khānfū (the modern Guangzhou) at this time. The Chinese emperor even appointed a representative in Khānfū, who settled disputes arising between them and locals, served as imam, and ‘prayed for the sultan of the Muslims.’37 As for the route, cargo was hauled from Basra, Oman and elsewhere to the port of Siraf (Iran), where it was loaded onto ships bound for China.

The tenth-century geographer and encyclopaedist al-Masʿūdī reported that agarwood, cloves, aromatics, saffron musk and all perfumes came from India; camphor, sandalwood, nutmeg, cardamom and cubeb from present-day Vietnam; and amber, saffron and ginger from Spain.38 The same author provided a list of some twenty-five aromatics that were available in his day; in addition to those already mentioned, it includes costus, lentisk gum, ladanum and storax gum.39 Surprisingly, there is no reference to the oldest and one of the most-utilised spices, pepper, which, according to Ibn Khurradādhbih, was sourced from Kīlah (identified as Kra, in the Malay Peninsula).40 Equally interesting is the absence of references to the banana, which was known very early on, as it appeared as an ingredient in al-Warrāq’s treatise (in a drip pudding), and in a few more recipes in Kanz41 and Wuṣla.42

Besides the specialised treatises, information about food and dishes can be found in a variety of other sources, such as manuals composed for market inspectors (muḥtasib), for whom monitoring the production of food and purity of ingredients was a key responsibility. And in a culture that appreciated good food, it is not surprising that it played an important part in literary works, too.43

Arabic culinary literature may appear to have burst on the scene out of nowhere, but nothing emerges out of a vacuum, of course, especially if it is related to something as vital as food and drink. Although evidence is sometimes thin on the ground, it is possible to identify some antecedents of mediaeval Arab cooking.

Rather unsurprisingly, the oldest inspiration comes from within the Near East, in ancient Mesopotamia, for which evidence has survived in the form of three cuneiform tablets containing a total of some thirty-five ancient Babylonian recipes, dating from 1700 BCE.44 There are a number of similarities with mediaeval Arab recipes, first and foremost in terms of the ingredients. Many of the future staples, such as honey, vinegar, cumin, mint, coriander, garlic, onions and leeks are already here. The amounts of seasonings used also sound familiar, with up to ten condiments in one dish, some of which are cooked in the broth, others added at the end. As for ingredients, most of the recipes are meat based (including grasshoppers), though there is also a green wheat porridge (which would become a harīsa later on). There is already sheep’s tail fat (added after boiling), the use of multiple meats in one dish, or breads baked along the wall of an oven. In terms of techniques, most of the dishes are stews or broths, though there are some pickles as well.

One of the most interesting dishes is a lamb broth, which besides fat, onion, coriander, cumin, leek and garlic, calls for ‘crumbled cereal-cake’. This bears an uncanny resemblance to one of the few dishes attested in pre-Islamic Arabia and famous still today – the tharīd (bread sopped in a thick meat and vegetable broth), which was basic fare among Bedouin and allegedly a favourite of the Prophet, himself.

Ancient Greece and Rome is another connection worth exploring, and the medical and pharmacological works, such as those by the botanist Dioscorides (first century CE) and the physician Galen of Pergamon (d. ca 216 CE), contain a lot of information about foods and ingredients.45 However, when it comes to cookery books, the sources all but dry up. The genre appeared in the 5th century BCE but most of the works are lost, with only fragments remaining. Another, equally scanty source are the occasional references to food and matters culinary in Greek literature, for instance in gastronomic poetry and comedies.46 This dearth of sources is all the more disappointing as there emerged a culture of gastronomy which used exotic spices and fruits, many of them introduced as a result of Alexander’s campaigns. Greek cooks already made use of saffron, sumac, coriander and cumin, albeit in relatively low quantities as they were thought by some scholars to ruin the taste of the food, and should more appropriately be used in wine. Vegetables were not part of dishes, but were eaten as a side, with bread.

The Romans developed gastronomy to new levels of sophistication and extravagance, as shown, for instance, in Petronius’ Satyricon (first century CE). It is in fourth-century Rome that 478 recipes were gathered in a book called De Re Coquinaria (On the Art of Cooking), which has been attributed to Caelius Apicius, and is the only extant complete cookery book before the Arabic treatises.47 Like in the mediaeval Arabic tradition, the recipes reflected dishes of the higher classes, and revealed a high degree of technical proficiency in the kitchen, with numerous ingredients (often more than ten), including many of the same spices found in Arab cooking, and specialised equipment.

Most of the dishes involve meat, but there are several for fish, as well, and all were served slathered in sauce. Similarities with later Arab cuisine include preserves, salted meat and fish, and especially the use of hitherto unknown aromatics like asafoetida and spikenard as a result of the expansion of Roman trade. The abundant use of spices like cumin, coriander, rue and pepper means that someone dining in Baghdad in the tenth century would probably have had a sense of ‘déjà-goûté’ with many of Apicius’ dishes.

One of the key ingredients in Roman cuisine, particularly as a sauce base, was a condiment already used by the Greeks. Known as garum (Greek garos), or liquamen, it denoted fermented fish, which served to provide the salty flavour.48 The sources also mention muria, which was brine, or the liquid in which fish, vegetables, etc. have been pickled. Etymologically, the latter would appear to have much in common with a substance the Arabs referred to as murrī, a condiment resulting from an elaborate process of rotting and fermenting some cereal grain (often barley), though a few recipes (mainly from the Muslim West) called for fish.49 David Waines made a case for the existence of two distinct types of murrī, at least in al-Andalus and North Africa: one based on cereal (probably pre-Islamic), and another on fish (similar to garum).50 In terms of usage, it is worth noting that the Arab murrī is found only in savouries, while the Romans used garum in both savoury and sweet dishes. A modern recreation of murrī revealed that it tastes like soya sauce, which, of course, is also the result of mould and fermentation.51

We are on much more stable ground with a potential Persian (Sasanid) influence on mediaeval Arab cuisine, even if no cookery manual has survived that predates the Arabic works. The evidence, some of it circumstantial, is both culinary and lexicological.

The earliest source can be found in Middle Persian (Pahlavi) wisdom literature and involves a story from the late sixth or early seventh century, entitled Khusraw ī kawādān ud rēdak-ēw (Khosrow son of Kavād and the Page). It comprises a dialogue between the king and a page, who is questioned about his knowledge of various aspects of cultured life.52 It is the questions on foods and wines that most concern us, and they provide a great deal of information about the courtly culinary culture of the day. The similarities with the mediaeval Arabic works include the use of certain ingredients (e.g. types of meat), condiments, dishes and the use of sugar in savoury foods.

The Muslim conquest of Persia and the fall of the Sasanid Empire did not result in the loss of its culture. Not only was Iran never ‘Arabized’, its contribution on all levels, whether, political, religious (e.g. Shiism), cultural or literary, remained substantial, particularly during the Abbasid caliphate. And when it came to food culture, Persian sophistication was both an inspiration and an aspiration, and the above-mentioned story was even translated into Arabic by the (Persian-born) anthologist ʿAbd al-Malik al-Thaʿālibī (961–1038).53

Stews (khōresh),54 a mainstay of Sasanid cooking as well as in modern Iran, were taken to with gusto by the Arab conquerors, and make up more than half of the cooked dishes in the treatises. The Persian influence in the culinary lexicon appears in the names of ingredients and dishes, such as sikbāj (> sik, ‘vinegar’; bāj, ‘stew’) and zirishk (‘barberries’).

Despite the fact that no Persian cookery book remains today, some were in circulation as the author of the Andalusian treatise excerpts some details about hygiene and cooking taken from a book written by the Sasanian King Anushirwān (d. 579 CE).55

The Mongol conquest and rising influence of the Turks in the region from the thirteenth century onwards also led to food transfers, and in the present book one finds, for instance, tuṭmāj (a type of pasta), yāghurt (a yoghurt dish), and qāwūt (a nut confection).56

Another influence on mediaeval Arab cuisine, which has hitherto received little attention, comes from India. Yet the connection would appear to be an obvious one, if only because of the intense trading contacts and the sourcing of many spices and plants. Unfortunately, little evidence is available. Linguistically, there are the borrowings from Sanskrit, such as nārjīl (narikela, ‘coconut’, also known in Arabic as jawz Hindī, ‘Indian walnut’), kurkum (kuṅkuma, ‘saffron, turmeric’), or the rice dish known as bahaṭṭa (from the Hindi bhat, ‘boiled rice’)57 for which a recipe is found in a number of cookery books, including Zahr (No. 72).

Additional information is provided by the oldest extant source on Indian cooking in the Middle Ages, the so-called Mānasollāsa (Delight of the Mind), a Sanskrit text completed in 1129–30 by the South-Indian king Someśvara III. This encyclopaedic work is a valuable source for eleventh–twelfth-century Indian culture as it discusses a large number of subjects, including politics, astronomy, painting, medicine and poetry. The third book is devoted to food and dishes, some of which are somewhat similar to Arab dishes, such as meat cooked in sour fruit juices, rice beverages, fermented cereals and milk-based sweets.58 The mixture of spices also yields some interesting findings, such as the combination of betel leaf, nutmeg, mace, cloves and cardamom of the post-prandial paan, which are also the basis for a popular Arab spice mix, aṭrāf al-ṭīb, to which we shall return later.

Mediaeval Islamic medicine, like Greek medicine before it, took a holistic and preventative approach to health, within which food occupied a central place as ingredients and dishes alike also served as remedies. The theoretical framework that governed the body is known as ‘humorism’, which Muslim scholars inherited from the Greeks, particularly Hippocrates (ca. 460–ca. 375 BCE) and the already-mentioned Galen.59

It was based on four humours, rendered in Arabic as khilṭ (pl. akhlāṭ), which were fluids – blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile – regulating body and health. The humours were also linked to the four elements that make up all things: air, water, fire and earth. Each of them was linked to two of the so-called primary qualities – hot (ḥārr)/cold (bārid) and moist (raṭb)/dry (yābis): fire is hot and dry; air, hot and moist; water, cold and moist; earth, cold and dry. The elements are concentrated in the humours: air in blood (dam); water in phlegm (balgham); fire in yellow bile (mirra ṣafrā’); and earth in black bile (mirra sawdā’).

The humours were also endowed with the primary qualities associated with the element: blood was considered hot and moist; phlegm was cold and moist; yellow bile was hot and dry; and black bile was cold and dry. Finally, there was a connection between the humours and the season: blood with spring, yellow bile with summer, black bile with autumn, and phlegm with winter.

A person’s physical health and personality were linked to the balance of the humours – also known as the ‘temperament’ (mizāj); if black bile, for instance, predominates, the individual has a cold and dry (or melancholic) temperament, which is prone to sadness. Illness was viewed as the result of an imbalance in the humours, with balance being restored through medical treatment and/or diet as foods were linked to varying degrees (up to four) of the primary qualities. The need for equilibrium also manifested itself in a recommendation of temperance over excess not just in ingredients, but also in food, in general.

The identification of the temperament of foodstuffs was not a precise science and there is a great deal of variation in the medico-pharmacological literature, not just in the intensity of the quality, but the qualities themselves. For instance, rice was considered cold and dry in the second degree by some, but hot (in the first degree) by others, whereas onions appear as hot (third or fourth degree) and dry (third or fourth degree), or moist (third degree). Varieties of the same substance could also demonstrate different temperaments; sweet pomegranates were cold and moist, while sour ones were cold and dry. In practice, this meant that, say, an individual with an excess of phlegm (cold and moist) would be prescribed hot and dry foodstuffs (e.g. pepper) in order to counteract the properties and restore balance. Ideally, the food should be suited to the temperament, age and state of the diner, and the season.

Cooked dishes were also associated with the primary qualities, and thus had therapeutic properties. However, here, too, there was considerable variation in the alleged properties. In most cases, there appears to be no obvious cumulative effect as the medicinal effects of a dish were often unrelated to those of its constituent components.

In the cookery books there is sometimes ambiguity as to whether a recipe should be considered medicine or food, as preparations originally designed as a medicament were eaten for pleasure as well, such as stomachics (digestive medicine).60

An examination of the medical references across the manuals reveals that al-Warrāq’s is the odd one out by the amount of dietetic content. However, it is important to add that none of it was original and was copied for the most part from medical works, such as the Kitāb al-Manṣūrī fi ’l-ṭibb by al-Rāzī (d. 925 CE), who gained fame in Europe as Rhazes.61 The next attested treatise, by al-Baghdādī, contains none whatsoever. The same is true for Waṣf. The other works that include medical information are the Andalusian, Kanz and Zahr, which, in addition to specifying the medicinal properties of some recipes (e.g. aphrodisiacal or anti-emetic effects), includes the humoral properties of some key ingredients.

The earliest dated culinary information – though not actual recipes – can be found in medical and pharmacological works. There is, however, one source that includes a substantial number of recipes. The Minhāj al-bayān fīmā yastaʿmiluhu al-insān (The Pathway of Explanation Regarding that which Human Beings Use) by the Baghdad physician Ibn Jazla (d. 1100 CE) is a pharmacological dictionary containing over 2,200 entries, most of them plants and drugs, as well as over 200 food recipes.62 It is particularly significant since the earliest copy can be reliably dated to Rajab 489 AH (June–July 1096 CE),63 whereas the oldest cookery book manuscript (al-Baghdādī) dates from 1226 CE. The book was quite the bestseller in its time, as around fifty manuscript copies have survived to the present day.

It is safe to hypothesize that Ibn Jazla was not the creator of the recipes, but that they were culled from as yet unknown – and probably lost – sources (culinary and/or pharmacological), which may have constituted an immediate precursor, or the missing link, in the early history of the cookery books and thus, in a way, reversely mirror the food–drug continuum in which food became medicine. In parallel – or in a subsequent stage – there would have been the addition of adab elements (as in al-Warrāq), followed by the final stage of the recipe book. The Taṣnīf al-aṭʿima could well be another example of this additional stage in the early development of the culinary writings.

Evidence of the hypothesis is provided by al-Baghdādī’s autograph manuscript. Firstly, there are a number of extracts from the Minhāj added by another hand (and at a later date) in the margins of many of al-Baghdādī’s recipes.64 The marginalia include recipe variants, dietetic information about recipes or ingredients, and even entire recipes, as in amīr bārīsiyya (barberry stew)65 and ḥasā’ (soup).66

However, the influence far extends the margins as in a number of cases the recipes are near-identical, with only minor differences in, for instance, the title of the recipe, the sequence of instructions, or proportions of ingredients. In one case (khabīṣ), three of al-Baghdādī’s recipes appear under one entry in Ibn Jazla.67 In other cases, the borrowing is only partial. The recipes borrowed are predominantly (sweet) puddings, as well as some meat dishes. Although al-Baghdādī at no point acknowledged his source, the origin (‘Minhāj’) is mentioned at the end of each of the marginal additions, some of which include elements not copied from Ibn Jazla’s recipes, thus ‘restoring’ them to their original form.68 The most salient feature is the omission of the medical information which prefaces Ibn Jazla’s recipes. The two texts also share a number of other dishes with identical names but different cooking instructions, such as akāriʿ (trotters),69sikbāj,70shīrāz buqūl (a type of condiment),71samak musakbaj (fish stewed in vinegar),72 and samak mamlūḥ mamqūr (salted fish dish).73

While it is likely that al-Baghdādī borrowed the recipes directly from the Minhāj, not least because of the popularity of Ibn Jazla’s text and the fact that both men were from the Baghdad, it is, of course, possible that both copied from another, hitherto unidentified source.

The link between food and religion is an important one in Islam, and there are numerous references in religious texts, whether it be the Qur’ān or hadiths.74

The prohibition of certain foods in Islam is widely known, whether it is the unlawfulness of pork and alcohol, or the abstention from food in general between sunrise and sunset during the holy month of Ramadan. Less familiar to us today, perhaps, are the food prohibitions common amongst mediaeval Christians, whose diet was subject to religious stricture, not least that enjoying food was synonymous with gluttony, which was considered the sin committed by Adam and Eve and led to the Fall. As a result, restraint (often in the form of fasting) was the road to godliness and salvation. Things were different for the mediaeval Muslim, who was encouraged to enjoy the bounty provided by Allah (e.g. Qur. 7:32, 2:57), albeit without excess (7:31). Several of the cookery authors preface their books with a disclaimer and include the religious injunctions to endorse the enjoyment of their recipes. Al-Baghdādī, for instance, referred to wholesome food and drink as Allah’s graces, as well as being ‘the foundation of the body and the essence of life.’75

When it comes to religious prohibitions, references in the cookery books are few and far between. They tend to involve instructions not to let people who are in a state of ritual impurity touch certain dishes when they are being prepared. This usually referred to women on their period, but also includes touching something impure (e.g. blood, semen, faeces) beforehand, without washing, or being a non-Muslim. Interestingly enough, the dishes in question share the fact that they involve pickling or fermentation, as in a recipe for murrī in Zahr (No. 91).76

References to the religious status of wine (khamr), on the other hand, are conspicuous by their absence. This is particularly interesting because wine was frequently served at banquets, while both pre-Islamic and classical Arabic literature include numerous references to wine, which is the object of a special genre in poetry known as khamriyyāt.77 Leaving aside wine vinegar, which is not alcoholic, references to wine in the cookery books are extremely rare, irrespective of the context. In fact, there are only two in which wine is an ingredient, both of which are found in culinary treatises from the Muslim West; one is a recipe for a ‘fish murrī’78 and the other, a ‘chicken khamriyya’, which calls for about a pint of wine, which can be replaced, however, by the same quantity of honey.79 In the present text, unadulterated wine (sharāb ṣirf) is an optional ingredient (to lemon juice) in the preparation of a fish paste (No. 136). The treatise by al-Warrāq stands out by the fact that it has several recipes for making the beverage,80 but none that actually requires it.

Wine also received the attention of physicians and pharmacologists, such as the Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Bayṭār (d. 1248 CE) and al-Rāzī, who discussed both the beneficial and harmful effects of the beverage, without making any reference to its religious prohibition.81

Related to a verb meaning ‘to ferment’ (khammara), the word khamr is probably of Aramaic origin. In pre-Islamic Arabia, wine was mostly made from dates, or from raisins, honey, wheat, etc., and was traded predominantly by Jews and Christians.

Another word for wine, qahwa, related to a verb meaning to lose appetite, would become more famous since it came to mean ‘coffee’. When the bean was introduced in the Peninsula in the fourteenth century, it acquired its name from the fact that its colour resembled that of qahwa. For their part, Arabic lexicographers, such as Ibn Manẓūr (d. 1313 CE), the author of the famous Lisān al-ʿArab (The Tongue of The Arabs), attributed the semantic shift to the fact that both wine and coffee suppress the appetite.

In the Qur’ān, the views on wine vary significantly. In verse 16:67, there are no issues with wine; in fact, it is praised as one of the signs of God’s grace: ‘And from the fruit of the date-palm and the vine, you get out wholesome drink and food: behold, in this also is a sign for those who are wise.’ This is corroborated in 16:69, where it is said to be healing to human beings. There is a slight shift in verse 2:219, which has an admonishing tone: ‘They ask you concerning wine and gambling. Say: “In them is great sin, and some profit, for men; but the sin is greater than the profit.”’ In other words it is sinful, yet contains some benefits. In the hadith literature, the change is said to have occurred as a result of the Prophet witnessing the effects of drunkenness, such as his uncle mutilating ʿAlī Ibn Abī Ṭālib’s camels, and believers performing their rituals badly when in their cups. Reference to the latter appears in verse 4:43: ‘do not approach prayer while you are intoxicated until you know what you are saying or in a state of janāba (major ritual impurity)’. Through a principle known as abrogation, the verse (5:90) that supersedes the others is one that refers to khamr (together with gambling, making sacrifices to idols and divining arrows) as a satanical abomination. This is also the line that is consistently found in hadith, where the drinking of wine is adjudged one of the major sins.

There existed yet another word for wine, nabīdh, which is not mentioned in the Qur’ān, and applied to any kind of intoxicating drink, irrespective of the substance that was left to steep in water until it fermented.82 Unlike khamr, which still means ‘wine’, nabīdh has maintained its general meaning and in some vernaculars still refers to any kind of alcoholic drink. In others (for instance, Egypt), nabīdh and khamr are synonyms.

In the culinary tradition, only al-Warrāq mentions nabīdh, as an ingredient,83 as well as several recipes to make the beverage itself.84 The absence in later manuals may reflect a change in attitude and a departure from the ‘old’ Abbasid banquets where wine flowed freely.

To most Muslim scholars, the (un)lawfulness of ‘wine’ is related to whether or not it has been fermented outside for more than three days. When a drink is made through boiling, rather than fermentation, it was also allowed.85 This explains why wine vinegar, which is the usual type of vinegar used in culinary treatises, was lawful.

This also covers another substance, a kind of beer known as fuqqāʿ, of which there are several recipes in most of the cookery books, including Zahr (Nos. 166–8). It involved a heavily spiced drink (based on, for instance, a cereal, rice, or honey) that was allowed to ferment for no more than one day, and is thus not intoxicating.86 Though limited, the fermentation aspect did continue to cause disagreement among scholars. Al-Rāzī listed it among the ‘non-intoxicating beverages’, together with oxymel and honey water, but stated that it ‘rushes to the head (kathīr al-ṣuʿūd ilā ’l-ra’s).’87 The issue of the lawfulness of fuqqāʿ never reached the Muslim West as there are no references to the beverage in the Andalusian or al-Tujībī.

Mediaeval Muslim society was a true melting pot of ethnicities and religions, which made for a rich environment for exchanges of all sorts, including food. Jews and Christians were found at all levels of society; indeed, many of the physicians were from those backgrounds.

What do the culinary treatises say about this diversity? Perhaps surprisingly, there are only two treatises, one from either side of the Muslim Mediterranean, that contain dishes that are identified as being Jewish.

The Near Eastern Waṣf contains a recipe for Jewish meatballs (makābīb al-Yahūd), which are made with lean meat, pistachios, cassia, pepper, salt, parsley, mint, celery leaves and eggs.88 Interestingly enough, the only other copy of the treatise names the recipe ‘Meatballs cursed by the Jews’.89 There does not appear to be anything identifiably Jewish about the dish, whether it be the ingredients or preparation. The fact that the tendon (ʿirq) should be removed from the meat led Perry to suggest a connection with Jewish dietary law (kashrut), which proscribes the sciatic nerve.90 This might have been a viable hypothesis, if it were not for the fact that other Arabic cookery books (Zahr, Kanz and al-Baghdādī) recommended removing tendons before cooking meat. And what about the alternative name of the dish being ‘cursed by Jews’?

In the Islamic West, the anonymous Andalusian treatise contains six purportedly ‘Jewish’ recipes: (stuffed) ‘Jewish partridge’ (ḥajala yahūdiyya); ‘Jewish hen’ (farrūj yahūdī); two ‘Jewish partridge’ (ḥajala yahūdī [sic]) dishes; ‘stuffed, buried Jewish dish’ (lawn yahūdī maḥshū madfūn); and ‘stuffed aubergine with meat’ (bādhinjān maḥshū bi-laḥm).91 Other than the name, there do not appear to be any identifiably Judaic features, either in the ingredients, or references to the use of the dishes in, for instance, religious rites or feasts. The only things the recipes have in common is that they tend to require lamb or poultry and all of them involve stuffing. None of this, however, sets them apart from the other recipes, either in the Andalusian manual, or any other for that matter. And then there is the fact that the first three recipes and the fifth all end with ‘and serve it in shā’ Allāh (‘Allah willing’).’

Guillaumond92 reported that the editor of Anwāʿ al-ṣaydala