2,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 2,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

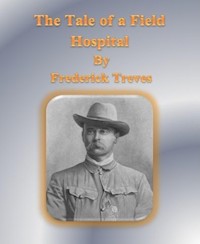

In "The Tale of a Field Hospital," Frederick Treves presents a poignant and intimate account of the experiences faced in a military hospital during World War I. Through vivid narratives and astute observations, Treves captures the harrowing realities of wartime medicine, detailing the physical and emotional toll on both the wounded soldiers and the medical staff. The literary style is characterized by a blend of stark realism and compassionate empathy, set against the broader backdrop of the early 20th-century medical landscape and the societal upheaval caused by the war. Treves's use of descriptive language immerses the reader in the chaos and urgency of a field hospital, showcasing both the triumphs and tragedies of wartime healthcare. Frederick Treves, a prominent British surgeon and writer, had firsthand experience as a battlefield doctor, which profoundly shaped his perspective. His earlier career, including his involvement in notable surgical procedures, provided him with the expertise to convey the complexities of war medicine. Treves's dedication to patient care and his deep sense of humanitarianism compel him to share these riveting experiences, offering insights into the psyche of those involved in wartime medicine. This book is a must-read for those interested in medical history, World War I, and the human condition. Treves's articulate storytelling not only informs but also evokes empathy and reflection on the sacrifices made by countless individuals during times of crisis. Readers will find in this work a compelling narrative that resonates with the importance of understanding our collective past and the enduring spirit of survival. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Tale of a Field Hospital

Table of Contents

Introduction

At its core, The Tale of a Field Hospital traces the uneasy meeting of medical order and martial chaos, where the discipline of healing is tested by scarcity, urgency, and the human cost of conflict, and where the physician’s duty becomes a daily negotiation between compassion, endurance, and the limits of what care can accomplish under fire.

This book is a work of non-fiction by Frederick Treves, a British surgeon, grounded in his wartime medical service and first published in the early twentieth century. Set against the South African War (1899–1902), it focuses not on battles but on the spaces where the wounded are received, assessed, and treated. Readers encounter the rhythms of a military medical unit operating in the field, with its routines, improvisations, and constraints. As a document of its time, it contributes to both war literature and medical narrative, offering a contemporaneous perspective on how organized care tried to keep pace with industrialized warfare.

The premise is straightforward and absorbing: Treves recounts the life and labor of a field hospital as it moves with campaigns, receives casualties, and contends with terrain, weather, and supply lines. Instead of grand strategy, the narrative emphasizes process—transport, triage, anesthesia, dressing, and recovery—along with the coordination between surgeons, orderlies, and support staff. The result is a close-up portrait of care under pressure, conveyed with professional clarity and an eye for telling detail. Readers should expect an observational voice, an even, reflective pace, and a mood that balances sobriety with quiet respect for the people who pass through the canvas walls.

Several themes stand out: the fragility and resilience of bodies; the discipline and improvisation of medical teams; and the moral weights borne by those who must decide, rapidly and repeatedly, how to allocate time, skill, and scant resources. The book attends to the boundaries of medical possibility, showing how standards developed in peacetime are stretched by wartime necessity. It also explores the fellowship of service—how shared labor, routine, and ritual hold a hospital together when certainty is scarce. Without dwelling on tactics or politics, the narrative illuminates the everyday ethics of care at the edge of catastrophe.

For contemporary readers, the book’s relevance lies in its clear-eyed attention to systems of care under strain. Its scenes of triage and logistics speak to ongoing questions in emergency medicine, disaster response, and humanitarian work: how to act decisively with incomplete information, how to steward resources, and how to support caregivers who must absorb repeated trauma. The historical distance allows reflection without sensationalism, while the specificity of observation makes the account feel immediate. As a record of early modern military medicine, it helps to trace the lineage of practices that continue to shape surgical technique, sanitation, and patient management today.

Stylistically, the writing favors precision over flourish, with a clinician’s attentiveness guiding the narrative tone. The emphasis on observation yields vignettes rather than grand arcs, and the cumulative effect is one of quiet intensity. Treves’s perspective remains humane without sentimentality, attentive to procedure yet mindful of the people behind the cases. The prose offers enough context for non-specialists while maintaining the professional texture of a surgeon’s account. The pace alternates between methodical routine and sudden urgency, reflecting the stop-start tempo of hospital work where uneventful hours can give way, abruptly, to exacting, life-altering minutes.

Approached as both historical testimony and a human document, The Tale of a Field Hospital invites readers to consider how care is organized, delivered, and sustained when conditions are least forgiving. It offers the intimacy of a practitioner’s bench notes and the steadiness of reflective reportage, opening a window onto the infrastructures and emotions that underwrite medical duty in wartime. Without relying on spectacle, it builds a durable sense of place and purpose, rewarding attention with insight into the textures of service. The result is an enduring meditation on responsibility, skill, and the quiet courage that accompanies the work of healing.

Synopsis

The Tale of a Field Hospital is Frederick Treves’s firsthand account of medical service during the South African War, presented as a sequential record rather than a strategic history. A surgeon attached to a field unit, Treves describes the setup, movement, and work of a frontline hospital supporting British forces in Natal. He outlines the hospital’s purpose within the army’s medical chain, emphasizing practical detail over personal reflection. The narrative follows his unit from arrival through successive campaigns, noting how the hospital adapts to terrain, weather, and the pace of operations. The book aims to document procedures, conditions, and results plainly and precisely.

Early chapters establish the hospital at Frere and nearby railheads, explaining the arrangement of tents, operating space, and stores. Treves details personnel roles—surgeons, dressers, orderlies, and transport teams—and the coordination needed to receive convoys of wounded. He describes triage at the tent lines, initial dressings, and the preparation of cases for surgery or evacuation. Supply lists, water points, and lighting are specified to show how work continued after dark. The account introduces the routine of a field hospital: sudden surges of admissions after engagements, intervals of maintenance and reorganization, and constant readiness for movement forward or back.

A principal section covers the influx of casualties from actions along the Tugela River, notably after Colenso. Treves outlines how stretcher-bearers and ambulance wagons collected the wounded under intermittent fire and difficult ground, and how the hospital received them through the night. He describes the identification of patients, the tagging of injuries, and the immediate sorting of urgent cases. Record-keeping and the safeguarding of personal effects are noted alongside clinical duties. The chapter emphasizes the need to stabilize patients for either operation or transport, with particular attention to shock, bleeding, and the risks of delay.

The narrative then turns to the ambulance train, the essential link from the field to base hospitals. Treves explains the conversion of carriages, the placement of stretchers, and the methods used to reduce jolting during travel. He describes onboard monitoring, the management of pain and hemorrhage, and the provisioning of water and dressings en route. Stations along the line serve as transfer points to larger facilities at Mooi River and Pietermaritzburg. The train’s timetables, loading drills, and communication with the field hospital illustrate how transport capacity shaped surgical decisions and influenced patient outcomes.

As the unit moves toward Chieveley, Treves presents a concise account of contemporary field surgery. He contrasts the clean perforations from small-calibre rifles with the devastating lacerations from shell fragments. The narrative outlines aseptic preparation, the use of chloroform, and the management of shock and exposure. Limb injuries are weighed for conservative treatment versus amputation; abdominal, thoracic, and head wounds are discussed with regard to prognosis and timing. The text notes rates of recovery, the importance of rest and nutrition, and the challenges of repeated dressings in heat, dust, and wind. Examples are given to illustrate typical courses rather than individual stories.

Later chapters describe renewed fighting on the Tugela heights, including the aftermath of heavy engagements such as Spion Kop. Treves records how mass casualties strained beds, stores, and personnel, prompting temporary expansions and improvised theatres. He notes arrangements for burial parties and the observance of truces to remove wounded under the Geneva Convention, as well as the transfer of enemy patients and exchanges with Boer medical staff. Documentation of wounds, lists of the dead, and the forwarding of effects are presented as routine duties. The account maintains focus on process amid rapidly changing tactical conditions.

The book devotes space to nursing and hospital administration. Treves outlines the work of orderlies, volunteers, and chaplains; the preparation of food; and the securing of clean water. Sanitation measures address waste disposal, flies, and tent spacing. He describes dressings parades, night watches, and the distribution of comforts to convalescents. The text notes the return-to-duty pathway for minor cases and the scheduling of train evacuations for serious ones. Throughout, discipline, clear roles, and standardized routines are emphasized as the means to sustain care despite weather, fatigue, and the irregular flow of casualties.

Disease receives separate treatment, with enteric fever prominent. Treves summarizes camp hygiene principles: latrine placement, water testing, segregation of suspected cases, and disinfection. He compares morbidity and mortality from disease with those from battle, indicating how non-combat illness can dominate hospital occupancy. The narrative records improvements in supplies and organization over time, including better tents, stretchers, and sterilization capacity. Weather effects—heat, thunderstorms, and cold nights—are cited for their influence on recovery and the risk of exposure. The section presents disease control as integral to the field hospital’s mission, not ancillary to surgery.

The concluding portion situates the field hospital within the broader system of modern war: rapid transport, concentrated firepower, and dispersed battlefields. Treves’s account argues implicitly for preparedness—trained personnel, reliable transport, ample sanitation, and efficient recording—as the determinants of medical success. He portrays the hospital as a mobile service bridging front and base, designed to stabilize, sort, and move patients as conditions dictate. The narrative closes without speculation on strategy, offering instead a factual summary of methods and results. Its central message is the practical organization of care under campaign conditions, shown through continuous, ordered observation.

Historical Context

The Tale of a Field Hospital unfolds in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899–1902), principally across the British lines of communication in Natal, the Orange Free State, and the Transvaal. Frederick Treves, a leading London surgeon, served with the British medical services amid tented encampments, dusty railheads, and rapidly shifting front lines shaped by mobile Boer commandos. The setting is defined by long supply lines, a harsh veld climate, and the logistical constraints of campaigning armies relying on railways and wagon transport. The book’s scenes arise from the pivotal months of 1899–1900, when medical units struggled to stabilize wounded and sick soldiers under wartime conditions.

The war itself was the decisive event: a clash between the British Empire and the Boer republics—the South African Republic (Transvaal) under Paul Kruger and the Orange Free State—rooted in imperial ambitions, Uitlander rights, and the gold-rich Witwatersrand (discovered in 1886). Tensions escalated after the Jameson Raid (1895–96), and hostilities began on 11 October 1899. Britain mobilized forces from across the empire—regulars and contingents from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—eventually surpassing 400,000 troops in theater. Treves volunteered as a surgeon early in the conflict; his 1900 account reflects firsthand service with British medical formations, translating the war’s strategic shifts into the daily realities of triage and surgery.

Early British setbacks during Black Week—Stormberg (10 December 1899), Magersfontein (11 December), and Colenso (15 December)—created sudden surges of casualties, overwhelming field hospitals. The sieges of Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking stretched into 1900, with reliefs in February–May. Spion Kop (24 January 1900) exemplified the war’s brutal terrain, yielding over 1,500 British casualties on crags difficult to evacuate. Hospital trains ferried wounded from railheads to base hospitals at the Cape and along the lines. Treves’s narrative mirrors these operational pressures: his field hospital absorbs the human consequences of tactical misjudgment, piecemeal assaults, and protracted siege warfare that taxed surgical capacity and evacuation systems.

Disease dominated the war’s mortality profile: of roughly 22,000 British deaths, more than 14,000 were from illness, chiefly enteric (typhoid) fever, dysentery, and pneumonia. After the British occupied Bloemfontein in March 1900, a notorious typhoid outbreak—fueled by contaminated water and inadequate sanitation—produced thousands of cases, swamping medical facilities. Preventive measures lagged behind bacteriological knowledge, and camp crowding amplified transmission. Treves’s observations on bed shortages, sanitary improvisation, and the grim arithmetic of triage reflect this epidemiological reality. His account embodies the strategic lesson that logistics and public health—not merely battlefield valor—decide outcomes, prefiguring later systematic attention to water supply, latrines, and vector control in imperial campaigns.