16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

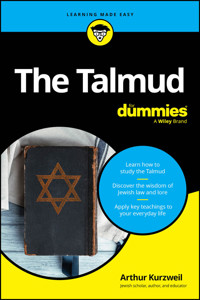

Unlock the wisdom, guidance, and spiritual insight of the Talmud

The Talmud For Dummies introduces you to the Jewish guidebook on life and overall cornerstone text of Judaism, the Talmud. This easy-to-understand book makes the Talmud's 63 volumes approachable, so you can deepen your understanding of Jewish teachings. You'll learn about what the Talmud is, get guidance on how to approach Talmud study, and find direction on how to apply the wisdom of the Talmud in your personal and spiritual life.

- Read the fascinating history of the Talmud and the key figures who shaped it

- Get advice on how to study the Talmud and uncover its spiritual teachings

- Apply Talmudic wisdom to everyday life, including marriage, divorce, kosher practices, prayers, and even humor

- Become well versed in the law of Rabbinic Judaism

The Talmud For Dummies is your go-to resource for anyone who wants to study the Talmud, including complete beginners and those looking to brush up their knowledge. Discover the timeless teachings of this profound and influential book with The Talmud For Dummies at your side.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

The Talmud For Dummies®

To view this book's Cheat Sheet, simply go to www.dummies.com and search for “The Talmud For Dummies Cheat Sheet” in the Search box.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

About This Book

Conventions Used in This Book

Foolish Assumptions

Icons Used in This Book

Beyond the Book

Where to Go from Here

Part 1: Introducing the Talmud

Chapter 1: What is the Talmud?

Defining the Talmud

The Talmud: The Central Pillar of Judaism

The Layout of the Talmud: What Are You Looking At?

What’s It All About? Everything!

The Great (and Not So Great) Rabbis of the Talmud

Women in the Talmud

Studying the Talmud — Some Things to Keep in Mind

Chapter 2: Tracing the History of the Talmud

Introducing Rashi: The Great Commentator of the Talmud

Post-Rashi: The Tosafot Period

Key Milestones in Jewish History

Key Events in Talmudic History

Chapter 3: Tackling the Talmud Today

Blessings for Studying Torah (Including the Talmud)

Rituals for Studying Torah

Finding a Study Partner

Chapter 4: The Antisemitic War Against the Talmud

Falsehoods that Fueled the War Against the Talmud

Religious Intolerance through History

Jewish Persecution in Modern Times

Chapter 5: Key Terms and Concepts From the Talmud

Marriage

Courts and the Law

Human Behavior

Personal Status

Crimes

Mitzvot

Human Emotions

Part 2: Opening the Talmud

Chapter 6: Navigating the Talmud

Where to Start? Anywhere!

Introducing the Talmud’s Parts

Understanding the Layout of a Talmud Page

Other voices in the margins

The Stories and Laws of the Talmud

Chapter 7: Greeting the Great Talmudic Masters

Praising the Rabbi Currently Known as Prince

Rabbi Akiva: Announcing the Talmud’s Superstar

Pairing Two by Two (Rabbis, Not Animals)

Grasping the Unforgettable Nachum Ish Gamzu

Excommunicating Rabbi Eliezer the Great

Meeting the Talmud’s Heretic

Recognizing the Five Sages in the Passover Hagaddah

Following the Four Rabbis into the Mystical Garden

Seeing What Others Say

Chapter 8: Apologies and Reflections on Women in the Talmud

Looking at How Women Are Represented in Judaism

Women as Orthodox Rabbis? Why Not?

(Baseless) Arguments Against Women Studying and Teaching the Talmud

Teaching the Talmud as a Woman

Educating Jewish Women

Meeting the Women in the Talmud

The Times They Are A-Changin’

Seeing What the Torah Has to Say

Chapter 9: Thinking Like a Talmudic Rabbi

Absurdities as a Tool for Exploring Truth

Clarifying the Law Through Absurdities

Part 3: Living the Talmud Way

Chapter 10: Observing the Holidays as Holy Days

Shabbat: The Day of Rest

Preparing for Shabbat: Make an Effort!

Lighting Up the World on Chanukah

Dwelling in a Sukkah on Sukkot

Masquerading on Purim

Preparing for Passover

Rosh Hashanah: It’s Not a Party

Yom Kippur: Not a Day of Judgment After All

Chapter 11: On Eating, Praying, and Harmful Speech

Eating — But Only if It’s Kosher

Praying and Blessing

Harmful Speech

Chapter 12: Breaking Taboos: The Talmud’s Surprising Views on Sex

Sexual Intimacy in the Talmud

Exploring Talmudic Perspectives on Marital Sex

Chapter 13: Litigating the Talmudic Way

Jewish Courts

Understanding Jewish Law

Justice in the Talmud

Following the Laws

Part 4: The Part of Tens

Chapter 14: Grasping Ten Important Talmudic Concepts

Eilu v’Eilu

Siyag L’Torah

Makhloket

D’oraita and D’rabanan

Tza’ar Ba’alei Chayim

Kal Vakhomer

Pikuach Nefesh

Bediavad

Kinyan

Hefker

Chapter 15: Ten Books for Your Talmud Library

Koren Talmud Bavli

Talmud Bavli: The Schottenstein Edition

William Davidson Talmud

Reference Guide to the Talmud

Introduction to the Talmud

The Essential Talmud

Ein Yaakov

Who’s Who in the Talmud

Talmudic Images

The Talmudic Anthology

Some Additional Books on My Talmud Bookshelf

Appendix: The 63 Books of the Babylonian Talmud

Seder Zeraim (Seeds)

Seder Moed (Festival)

Seder Nashim (Women)

Seder Nezikin (Damages)

Seder Kodashim (Holy Things)

Seder Tohorot (Purities)

Index

Dedication

Connect with Dummies

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Chapter 6

TABLE 6-1 Overview of the Talmud Structure

TABLE 6-2 The Sedarim of the Mishna

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

FIGURE 1-1. A page of the Talmud, showing the Mishna, the

Gemara,

Rashi’s comme...

Chapter 8

FIGURE 8-1 The author, Arthur Kurzweil (left), with Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, disc...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Begin Reading

Appendix: The 63 Books of the Babylonian Talmud

Index

Dedication

Pages

i

ii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

The Talmud For Dummies®

Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Media and software compilation copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial technologies or similar technologies.

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Trademarks: Wiley, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHOR MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS WORK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION WARRANTIES OF FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES OR PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY SITUATION. THIS WORK IS SOLD WITH THE UNDERSTANDING THAT THE PUBLISHER IS NOT ENGAGED IN RENDERING LEGAL, ACCOUNTING, OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL SERVICES. IF PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE IS REQUIRED, THE SERVICES OF A COMPETENT PROFESSIONAL PERSON SHOULD BE SOUGHT. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. THE FACT THAT AN ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE IS REFERRED TO IN THIS WORK AS A CITATION AND/OR A POTENTIAL SOURCE OF FURTHER INFORMATION DOES NOT MEAN THAT THE AUTHOR OR THE PUBLISHER ENDORSES THE INFORMATION THE ORGANIZATION OR WEBSITE MAY PROVIDE OR RECOMMENDATIONS IT MAY MAKE. FURTHER, READERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT INTERNET WEBSITES LISTED IN THIS WORK MAY HAVE CHANGED OR DISAPPEARED BETWEEN WHEN THIS WORK WAS WRITTEN AND WHEN IT IS READ.

For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 877-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002. For technical support, please visit https://hub.wiley.com/community/support/dummies.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number is available from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-394-33212-0 (pbk); ISBN 978-1-394-33214-4 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-394-33213-7 (ebk)

Introduction

Maybe you heard someone say, “The Talmud says …” and you wonder just what the Talmud is. Well, the Talmud isn’t so easy to define. The word itself literally means learning, but the text by that name has a more complex true definition. The best way to understand what it is, as I explain in this book, is to jump right into it and swim around a little.

Think of studying the Talmud kind of like kissing. You can read about kissing, you can watch people kiss, you can understand the physiology of how to kiss, but if you want to learn about kissing, the best thing to do is to experience some kissing!

The phrase “the Sea of Talmud” has been used for many centuries to describe the Talmud, and the metaphor of a sea is apt. The Talmud, like a sea

Has no real beginning. Just jump in.

Is deep and vast. (The Talmud consists of 63 books, 517 chapters, 2,711 double-sided pages, and 1,860,131 words.)

Needs an experienced captain to navigate through its waters.

Can be dangerous; you might drown in it.

The Talmud presents a number of challenges to the reader:

Written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic

Contains no vowels, just consonants

Has incredibly complex text

Jumps from subject to subject without warning

Contains a lot of text that may seem irrelevant to modern life

Much more interested in questions than in answers

Discouraged already? Please don’t be. Translations of the Talmud into modern English use punctuation, and you can find commentaries that go word by word, phrase by phrase, to help even the absolute beginner navigate the Sea of Talmud. And I’m here to act as your guide while we explore the Talmud together.

Talmudic scholars say that the Talmud is written in the language of thought. In the same way that your thoughts can be all over the place almost simultaneously, the Talmud goes from topic to topic by free association.

Someone seeking spiritual enlightenment often has trouble with the Talmud. Why? Because the Talmud has a unique quality that probably no other religious text has: It requires the student to object to it! That’s right. In fact, if you’re not arguing with the text, you’re probably not really studying the Talmud correctly. Although the Talmud is a sacred book of the Jewish people, it encourages — no, it demands — that you question it.

The Inuit, indigenous people native to the Artic and Subarctic regions of North America, have a lot of words for snow in all its varieties. Although people often exaggerate exactly how many words they have, you can understand why they might have more words for snow than people who live in the tropics, for example. Exposure to and constant contact with something makes all its variations clear.

Well, the Talmud doesn’t have too many words for snow, but it has a lot of different words for questions. In fact, the sages who first recorded the Talmud built it on questions. While you study the Talmud, if you don’t ask questions, you can’t really participate in the process of Talmud study. The student of Talmud must eagerly question and re-examine accepted views.

The Talmud was originally compiled over 2,000 years ago, but it serves as the repository of thousands of years of Jewish wisdom.

Another unique aspect of the Talmud is that it treats both familiar topics and imaginary topics with the same degree of seriousness. In other words, to test an idea, the Talmud often invents an impossible situation in order to see the implications of the idea. For example, even though no flying machines existed when the Talmud was compiled, the Talmud doesn’t hesitate to say, “Well, what if we had a flying machine? What would that mean?”

The Talmud is filled with wisdom on almost every subject that you can imagine, but the text of the Talmud is more interested in the discussions that lead to the piece of wisdom, rather than merely the conclusion. When a Jewish child comes home from school, the appropriate question their parent asks isn’t, “What did you learn today?” Instead, they ask, “Did you ask a good question today?”

The writers and compilers of the Talmud never imagined a final, written work, but rather an open-ended text in which new questions and points of view are constantly asked. Talmudic scholars consider it a great achievement when a student of the Talmud comes up with an angle that no one had considered before.

About This Book

The Talmud is Judaism’s most important spiritual text, after the Bible. In fact, when students study a sacred Jewish text, they almost always study the Talmud. In The Talmud for Dummies, I aim to acquaint you with its key elements.

One of those elements is the great sages (wise rabbis) whose thoughts, ideas, and points of view appear in the pages of the Talmud. Probably a thousand different personalities have their words represented in the Talmud. Some of those sages appear only once in the entire text, while others appear hundreds of times. I introduce you to many of the key sages whose wisdom is laid out in the dialogues and debates in the Talmud.

The Talmud, unfortunately, has had a rough history, much like the Jewish people, who have had to face antisemites (people who are hostile to or prejudiced against Jews) since ancient times. Groups that have wanted to destroy the Jewish people over the centuries attacked and burned the Talmud because it’s such a vital text for Jews.

The Talmud also faces attack because of a widespread misunderstanding of its contents and intentions. When the sages debate a certain subject, the pages of the Talmud record all sides of the debate, even the points of view ultimately rejected by the debaters. When someone quotes from the Talmud, that quote may reflect an idea that the overall text fiercely rejects. But someone can say, “The Talmud says …” even if the sages in the Talmud condemn the statement that they quote. This quoting out of context has happened many times throughout history, with horrible results.

The Talmud has a fascinating history, but it also has a tragic side because of the ways in which those opposed to the Jews have manipulated and distorted its purpose. In this book, I take you through some of the highlights and lowlights of the Talmud’s story.

You can’t get around the fact that the Talmud has been something of a men’s club. The Talmud’s personalities are 99 percent male, so their points of view are, not surprisingly, male-oriented. Additionally, only men have studied the Talmud over the centuries (for the most part), so men have also written the commentaries. In The Talmud for Dummies, I confront this fact head-on and describe some of the efforts being made in our generation to change that situation.

The Talmud deals with every topic under the sun in its 63 volumes and countless commentaries. I often challenge people to name a topic, and I can show them where in the Talmud they can find a discussion relevant to the topic. I’ve never lost that challenge. The topics in the Talmud include subjects and situations limited only by the imagination. In The Talmud for Dummies, I select and explore a number of topics discussed in the pages of the Talmud that I hope interest you. Those topics include sex, the courts, marriage and divorce, eating, celebrating holy days, and humor.

Conventions Used in This Book

To help you navigate this introduction to the Sea of Talmud, I use the following conventions:

Definitions:

I define each Hebrew term the first time I use it, and I provide you with a pronunciation guide. I don’t use a standard pronunciation system, but rather an easy-to-use system based on plain-spoken English.

Dates:

When I provide a date, I use the secular abbreviations CE (Common Era), rather than AD (Anno Domini) and BCE (Before the Common Era) rather than BC (Before Christ). The year numbers are the same (meaning 500 CE is the same as 500 AD). I use a reference point that’s not Christian-oriented in fairness to our topic.

Foolish Assumptions

While I wrote this book, I had to make some assumptions about you. If you fit into any of these assumptions, this book is for you:

You feel pretty educated as a Jewish person, but you never really understood what the Talmud is all about.

You’ve heard about the Talmud but have no idea what it is.

You’ve heard the word

Talmudic

used in a negative way, implying overly complex or hair-splitting arguments.

You know nothing about the Talmud, or you’re aware of some common misconceptions about the Talmud that you want to clear up.

You’ve seen accusations online that the Talmud is somehow against non-Jews.

You’ve read some horrible quotations supposedly from the Talmud and you want to know the truth.

You want to learn about the Talmud, but you don’t want to struggle through an academic book about it. Instead, you want a friendly, informal, but accurate treatment of the subject.

You know some people who study the Talmud, and you want to try it, too.

Icons Used in This Book

You don’t have to read this book cover to cover (though you certainly can). Think of it as your guide to understanding the Talmud. You can jump straight to the topics that interest you most — like how debates between sages shaped Jewish law or what the structure of a Talmudic discussion looks like — or you can read it in order to build your knowledge step by step.

Keep an eye out for some special icons to help you navigate the book:

Look for this icon to find quick, practical insights that can help make sense of Talmudic study.

This icon highlights key concepts and ideas that you need to know in order to properly understand the text of the Talmud.

This icon points you to deeper discussions or background information if you want to explore further; but don’t feel obligated to read these paragraphs.

You can find common misunderstandings or tricky concepts that might lead to confusion pointed out with this icon.

Beyond the Book

In addition to the pages that you’re reading right now, this book comes with a free, access-anywhere online Cheat Sheet that summarizes some of our key advice at a glance. There are also two additional chapters — one on marriage and divorce in the Talmud and one that explores my personal minyan, the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain communal prayers. These chapters are available online, along with a glossary of key figures in the Talmud. To access this material, go to www.dummies.com/go/talmudfd.

Where to Go from Here

You might want to purchase a Steinsaltz Talmud volume (Koren Publishers). Out of the 42 volumes available, I recommend you start with Volume 1: Berakhot (pronunciation; Blessings). Just roll up your sleeves and chip away at it slowly. Take advantage of all of the notes provided by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz. You can also try The Essential Talmud (Basic Books) by Rabbi Steinsaltz. It’s not an easy book, but it’s worth the effort. I suggest additional further reading in Chapter 15.

Also, see whether you can find a Talmud class in a local synagogue. You can also watch some YouTube videos on the Talmud to introduce yourself to some ideas of this important Jewish text.

Part 1

Introducing the Talmud

IN THIS PART …

Discover what the Talmud is and why it holds such a central place in Jewish thought.

Trace the fascinating history of how the Talmud was compiled, preserved, and studied.

See how people engage with the Talmud today and why it continues to be relevant.

Explore historical attacks on the Talmud and efforts to suppress it.

Get familiar with essential legal terms used throughout Talmudic discussions.

Chapter 1

What is the Talmud?

IN THIS CHAPTER

Defining the Talmud and its importance

Navigating a page of the Talmud

Understanding the topics the Talmud discusses

Getting to know the rabbis — and where are the women?

Preparing to start studying the Talmud

The Talmud (TAL-muhd) is unlike any book you’ve ever seen. In fact, the Talmud isn’t a singular book at all; it’s a set of books — 63 in all — and each contains five books on almost every page! You don’t open the Talmud at the beginning and start reading from front to back. When I describe the Talmud to you, you may begin to get a sense of its unique structure. (The word Talmud means “study” or “learning.”)

In this chapter, I provide an overview of the Talmud in broad strokes and point you to where, in the rest of the book, you can read about everything in deeper detail.

Defining the Talmud

In a nutshell, the Talmud is the heart of Jewish learning — a sprawling, multi-layered conversation that has been unfolding for a few thousand years. It’s a collection of teachings, debates, and stories, centered on Jewish law and ethics, while touching on nearly every aspect of human life. At its core are the Mishna (MISH-nah), a concise compilation of legal principles, and the Gemara (“G” as in goat gehm-AH-rah), a vast commentary and exploration of those principles, written in the lively and questioning spirit of ancient Jewish scholars. Together, these texts create a dialogue that spans generations, inviting readers not just to learn, but to engage, question, and contribute. Far from being a dry legal code, the Talmud is dynamic, thought-provoking, and deeply human — a living testament to the power of study and the pursuit of wisdom.

If this topic sounds overwhelming, don’t worry. The Talmud might feel intimidating at first glance, but it’s one of the most fascinating and enriching works you’ll ever encounter. For centuries, it’s been a cornerstone of Jewish thought, shaping not only religious practices, but also a way of approaching life itself.

For me, the Talmud is deeply personal. It has challenged, inspired, and guided me in ways I never imagined. And for the Jewish people as a whole, it’s a treasure — an ongoing conversation that spans millennia. That’s why I’m writing this book: to help more people understand and appreciate the Talmud’s timeless wisdom and remarkable structure. Whether you’re curious, skeptical, or just eager to learn, this journey into the Talmud is one I’m thrilled to take with you.

The Talmud: The Central Pillar of Judaism

Many people who don’t know much about the Talmud think it’s the law book of Judaism, but that’s an over-simplification. One of the most concise descriptions of the Talmud I know comes from Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, who died in 2020 at the age of 83 and is considered by many to be the greatest Talmud scholar of the last century, if not the last 1,000 years. (I was a private student of his for over 35 years, and I wrote a book about him called On the Road with Rabbi Steinsaltz [Jossey-Bass, Inc.].)

Rabbi Steinsaltz once wrote, “If the Bible is the cornerstone of Judaism, then the Talmud is the central pillar, soaring up from the foundations and supporting the entire spiritual and intellectual edifice.” He called the Talmud the most important book in Jewish culture and described it as a repository of thousands of years of Jewish wisdom. He wrote, “(The Talmud) is a conglomerate of law, legend, and philosophy, a blend of unique logic and shrewd pragmatism, of history and science, anecdotes and humor.”

By the “Bible” Rabbi Steinsaltz is referring to the “Holy Scriptures” of Judaism: the Five books of Moses, the Prophets, and the Writings. Christians refer to this as the “Old Testament.”

You may find it strange to hear the Talmud, such a serious-looking and important text, described as full of anecdotes and humor; but I assure you, the Talmud is full of humorous stories.

The Talmud has also been a target of antisemitism (prejudice and hatred against Jews), which I discuss in Chapter 4. The Talmud has been slandered, vilified, and burned by antisemites who don’t know the first thing about the Talmud, what it is, or how it works. Popes, Nazis, and Jews who left the religion have all had a hand in the burning and destruction of volumes of the Talmud over the centuries.

Jewish tradition teaches that when God gave the Written Torah (also known as the Five Books of Moses) to Moses, God also gave him, orally, a detailed explanation of how to apply its teachings to life.

I discuss the history of the Talmud and its evolution from oral tradition to printed text in detail in Chapter 2.

The Talmud was never meant to be a completed document. Individual students add new commentaries and insights to the Talmud daily in the form of their own margin notes. More significantly, new editions of the Talmud have been published in our day, containing new contemporary commentaries. One excellent example of this is the Steinsaltz Talmud, also known as the Koren Talmud Bavli (see Chapter 15). Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz published an edition of the Talmud that includes his own commentary to help the modern student understand the text and participate in its discussions.

Rabbi Steinsaltz described the Talmud as a “photograph of a fountain,” where the photo captures just one frozen moment. At its best, the Talmud inspires the student to get involved in the discussion, having an active dialogue with the rabbis and sages whose teachings are recorded in the Talmud. Jewish scholarship permits and even encourages the student of Talmud to object to a text and demand further explanation and even justification. A person doesn’t read the Talmud passively.

The Layout of the Talmud: What Are You Looking At?

When you first open a page of the Talmud, you probably notice that it doesn’t look like any book you’ve seen — Figure 1-1 is an example of a page (I talk about the layout of the Talmud in Chapter 1). A portion of two books appears in the middle of each page. One is called the Mishna, and the other is called the Gemara. The Mishna is in Hebrew, and the Gemara is in Aramaic (the language spoken by people in Israel 2,000 years ago). The word Mishna means “instruction.” The word Gemara means “to finish” or “to complete.”

The Mishna provides the laws of the Oral Torah. But, like any book of law, many elements need explanation. What do certain words mean? How, more precisely, does a person perform or follow or understand those laws? That’s where the Gemara comes in. The Gemara (which is almost always longer than the accompanying Mishna) explains the laws in that Mishna; along the way, it also contains thousands of years of Jewish wisdom. The Gemara, if gathered together, also adds up to a book — or more accurately, to the size of many books.

A Gemara is almost always longer than its Mishna, which is usually rather short. The Gemara can sometimes go on for pages before a new Mishna appears. Together, the Mishna and the Gemara form the Talmud. With some exceptions, the Talmud generally contains a Mishna and its Gemara, another Mishna and another Gemara, for a total of 63 volumes, running down the middle of each page.

Just like the Mishna needs the commentary of the Gemara to help make it understandable, the Gemara needs a commentary that provides its explanation. A rabbi called Rashi (RAH-she), born in 1040 CE, wrote this commentary. Rashi’s commentary appears on almost every page of the Talmud and seeks to elucidate the Gemara. But much of Rashi’s commentary also needed explanations, and often objections and clarifications, and that part of a page of the Talmud is called Tosafot (TOE-sah-foat; addition) which includes Rashi’s grandsons. (For a lot more about Rashi, see Chapter 2.)

So, in a nutshell, the Mishna needs the Gemara, the Gemara needs Rashi’s commentary, and Rashi’s commentary needs the Tosafot. These elements appear throughout the volumes of the Talmud, page by page, and additional commentaries and references by important scholars over the centuries surround the text of the Talmud on each page to help the reader grasp its meaning and intention. Five things occur on each page, so you see five different texts simultaneously when you look at a single page. The Talmud is essentially a written record of discussions and debates on the part of at least 1,000 rabbis.

Are you dizzy yet? Just take it in slowly. It’s worth the effort. Because it is a unique document, the Talmud’s structure is not so easy to master.

Let’s imagine that the Mishna states a law that a cigarette is bad for your health. Then the Gemara might ask, “What’s a cigarette?” Then someone will try to define what a cigarette is. Someone else will say, “That sounds more like a cigar.”

Then, a discussion will occur, with several rabbis each weighing in on the difference between a cigarette and a cigar. After a while someone will ask, “What does the Mishna mean by “health”? Mental health, physical health?

FIGURE 1-1. A page of the Talmud, showing the Mishna, the Gemara, Rashi’s commentary, and the Tosafot.

Then someone will say, “Rabbi so-and-so smoked cigarettes for 90 years.” Someone will then tell a story about that same rabbi which has little if anything to do with cigarettes.

In the meantime, Rashi will suggest that the Mishna used the word “cigarette” to mean anything that one smokes. Then one of Rashi’s grandsons will insist that it said “cigarette” and it means “cigarette.”

It is the task of the student of Talmud to sort out the various points of view and join in the discussion.

Do you get the idea?

THE REVERENCE OF TALMUD SCHOLARS

Before you open the Talmud to see what’s inside, you first need to know how to treat a volume of the Talmud and how a student of the Talmud needs to behave. The Talmud isn’t just another book to grab or toss around. It’s not unusual, for example, to see a Talmud student pick up a volume or take it off a shelf and kiss it gently before opening it as a sign of respect and reverence. Before beginning to study from its pages, students recite a blessing of gratitude. Everyone exerts great effort to ensure that no volume of the Talmud ever drops to the floor. In preparation for studying the Talmud, students often wash their hands, not with soap and water, but in a ritualized way as dictated by Jewish tradition as described in the Shulkhan Arukh, the Code of Jewish Law. It's almost like a baptism of the hands, a spiritual cleansing. There is no English translation of the Code of Jewish Law, but there is an abridged version called the Kitzur Shulkhan Arukh (kit-tzur shool-khan ah-rukh; abridged Shulkhan Arukh) which will explain the handwashing ritual.

The great sages of the past recommend that students of the Talmud set aside time every day to study. Like working out at the gym, studying for 15 minutes a day is better than studying for 5 hours once a month. It’s the routine, sustained practice that is valuable. The great Jewish sages recommend regular study as part of a person’s daily routine. The sages also recommend that you find a regular study partner, called your khevrusa (khev-roo-sa). Not only does such a commitment keep a student on track. It also avoids the ease of fooling yourself into thinking that you understand what you’re studying. A perspective by someone else will challenge your understanding of the text.

What’s It All About? Everything!

In its vastness, the Talmud contains discussions about just about every topic under the sun — and above it, too! And the Talmud itself makes the point that the best subjects to study are the subjects that you want to study. For example, if you’re interested in child-rearing, look for texts in the Talmud about child-rearing. The Talmud deals, for example, with agriculture, dream interpretation, etiquette, theology, faith, mathematics, lavatory behavior, obesity, astronomy, medicine and medical advice, medical remedies, folklore, science, heresy, human habits, ethical problems, sexual life, astronomy, astrology, and business ethics.

If you want to study human sexuality, you can find plenty of material on that subject, too (See Chapter 12 for an exploration of this topic in the Talmud.) You can locate texts by subject in the Talmud in several ways, and I offer some suggestions about how to find what you’re looking for in Chapter 6.

In this book, I offer several chapters that deal with specific topics. I have pored over the Talmud, looking for texts that deal with the same general subject. Many Talmudic students and scholars perform this kind of research. Although many students of the Talmud study page by page, others want to locate the points of view of the rabbis on particular subjects, and so their research takes them all over the Talmud.

In The Talmud for Dummies, I discuss topics that I selected based on my own interests and those that I think would be general interests. These topics include Jewish holidays (Chapter 10), the Jewish court system (Chapter 13), human sexuality (Chapter 12), eating (Chapter 11), and praying (Chapter 11).

Because the Talmud doesn’t have a Volume 1, you can really jump in anywhere. Start with a Mishna and try to understand it. The Steinsaltz edition (which I talk about in Chapter 17) helps you to do that. Then, start to study the Gemara immediately following that Mishna, and work on it word by word, phrase by phrase, and sentence by sentence.

Again, a commentary such as what appears in the Steinsaltz edition not only helps you understand the text you are reading. I suggest you begin with one of these masekhtot (mah-sekh-toat; tractates, an organizational unit within the Talmud that examines a specific subject):

Berakhot

(beh-rah-

khoat

; Blessings): About prayers and blessings

Pesakhim

(peh

-sah

-kheem): About the holiday of Passover

Bava Metzia

(bah-vah met see-ah: The Middle Gate): About buying and selling, lost and found objects, and other down-to-earth topics

The masekhtot in the preceding list are far less technical than so many other sections of the Talmud.

The Great (and Not So Great) Rabbis of the Talmud

When you study the Talmud you need to know who said what because knowing who represented a certain point of view or action has an impact on understanding what is being said. (For example, if a poor man gives charity of a dollar it is more significant than if a millionaire gives a dollar to charity. Also “attribution” is an important principle in the Talmud. In other words, give credit where credit is due. Knowing who said what also gives greater insight into what is being said. In Chapter 7 and in the additional appendix, found at www.dummies.com/go/talmudfd, I introduce you to many of the rabbis and other personalities in the Talmud. An important thing to remember, however, is that the rabbis in the Talmud are people, not plastic saints. Judaism assumes that even the greatest rabbis are only human. They make mistakes and can express wrong opinions about things. Jews don’t make people into gods. Keep an open mind.

Some rabbis described in the Talmud have great authority and sterling reputations, so you interpret a remark made by one of them far differently than a statement made by a heretic, for example. In principle, the Talmud teaches that the wise person is the one who learns from everyone.

The words of a rabbi quoted in the Talmud just once or twice in the entire 63 volumes might have something profoundly important to teach. After a while, students of the Talmud get to know many of the rabbis who are quoted or described in the text, and you develop favorites. Two of my favorites are Rabbi Akiva and Nachum ish Gamzu (see Chapter 7 for details on these two sages and others).

Some of my favorite quotes are such because they challenge my thinking. Both Rabbi Akiva and Nachum ish Gamzu are quoted in the Talmud as saying essentially the same thing: “This too is for good.” This reflects a theological stance that assumes anything that the Almighty allows to happen to you is ultimately for good. Nachum ish Gamzu would always say, “This is also for good,” while Rabbi Akiva would say, “All that the Merciful One does, He does for good.” The idea seems outrageous. Is the suffering of an innocent child in any way good? Was the Holocaust in any way good?

In the first place, one never says “Everything is for good” to someone else, only to oneself. Also, this attitude is probably the most difficult approach to life in all of Judaism and other religions. Do I really believe that everything is for the best? My rational mind does not allow for such an approach to life. But I appreciate the teaching of these two sages because they challenge me spiritually. Could it be that in some inexplicable way, everything leads to something good? I can't deny that these two great sages in the Talmud represent this attitude. And I would be dishonest if I did not confess that I strive for an unwavering faith and optimism, even in the face of adversity.

Women in the Talmud

In Chapter 8, I make no bones about it: an apology — and more — is necessary regarding women and the Talmud. Few women are quoted in the text, and throughout history, few women have studied the Talmud. The good news is this: In our generation, more women than ever are studying the Talmud. And I predict that, in time, reputable Jewish publishers will issue Talmudic commentaries written by women.

I’m not the first person to suggest that if women had participated in Talmud study over the centuries, many of the issues dealt within the pages of the text would be treated quite differently. I’m not suggesting that the Talmud would always contain something called a woman’s voice. All people are, of course, unique. But I would contend that women’s voices in the text and commentary of the Talmud would make it a much different document. Chapter 8 deals with the important topic of the role (and lack thereof) for women in the Talmud in greater detail.

Studying the Talmud — Some Things to Keep in Mind

One of the complexities of the Talmud is that, although its 63 volumes are organized by topic (see Appendix for a list of all 63 Tractates of the Talmud), the Talmud is continually free-associating. Like conversations in real life, Talmudic discussions jump from topic to topic, at times returning to the original subject and sometimes not. Of course, two topics can seem to discuss two different issues when actually, at the heart of things, they deal with the same issue. The Talmud often quotes a particular rabbi on a certain topic, followed by, “Speaking of Rabbi So-and-So, he also said …” and then go to an entirely different subject.

Also, keep in mind that when studying the Talmud the best way to do it is to crack open the text and locate the eternal ideas embedded within it.

For example, a somewhat long passage in the Talmud discusses brides and how they look. You can easily judge this passage to be sexist. After all, the text doesn’t discuss how grooms look! But when you crack open the text and try to locate the eternal idea embedded within it, you can understand that the discussion is really about the permissibility to tell white lies. (I go into more detail about the discussion on flattering brides in the additional chapter on marriage and divorce, available on www.dummies.com/go/talmudfd.)

Rather than reject the discussion outright, the text can become a springboard toward a deep discussion about when you can tell a lie in good conscience. For example, I wouldn’t visit my grandmother in the hospital and say, “Grandma, you look worse than you did yesterday.” Although the Torah teaches you to tell the truth, sometimes a white lie, particularly not to hurt a person’s feelings, is what the situation calls for.

When you start exploring the Talmud, stay with it — you can find knowledge and inspiration on every page. Words of wisdom pop up in the Talmud often when you least expect it. And if you are reading a book or essay that quotes the Talmud and gives a page number from the Talmud, you might want to go to that page and read around it. Sometimes I get caught in a string of references from different tractates of the Talmud and I begin to explore an entirely different topic. I jump into the “sea of Talmud” and start to swim.

You can swim in the sea of Talmud, too.

Chapter 2

Tracing the History of the Talmud

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting to know Rashi, the great commentator

Meeting the group whose comments followed Rashi

Looking at key moments in Jewish history

Watching the evolution of the Talmud

The history of the Talmud (TAL-muhd; to study/to learn) is deeply intertwined with the broader history of Judaism because the Talmud represents the transmission and evolution of Jewish thought from ancient times to today. Before the Talmud, Judaism was primarily defined by the Written Torah (also known as the Five Books of Moses) and the Oral Torah, an accompanying body of interpretation and practice that was passed down orally.

Jews relied on these teachings to apply the laws of the Torah to daily life; but without a formal record, they risked losing or understanding those teachings over time. So, at one point, the Oral Torah was written down. Without commentary, a person might find the Torah difficult, if not impossible, to fully understand. For example, take a look at the very first sentence in the Written Torah, “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth.” The very first word in Hebrew, Berayshit (buh-ray-SHEET), actually has more than one interpretation. It could mean

“In the beginning” (In the beginning, God created)

“In the beginning of” (In the beginning of God’s creation)

“(God created) the beginning”

“With

reishit

(Ray-sheet), “God created with wisdom” (in the book of Psalms, Psalm 111:10, the word

reishit

refers to wisdom. This in turn refers to Torah as in a statement in a mystical Jewish text the

Zohar,

ZOWE-hahr) “God looked into the Torah and created the world”

Or it could even be a contraction of two words,

barah

(bah-RAH; created) and

shis

(shaysh; six), referring to six dimensions of being: Above, Below, Right (South), Left (North),In front (East), Behind (West).

And this is just the first word! For the Children of Israel to understand and grasp the Written Torah, they needed help.

This chapter delves into the Talmud’s history, beginning with the essential contributions of Rashi, one of its most influential commentators, whose work connects ancient traditions to future generations. I also present a condensed explanation of key events in the history of Judaism and, therefore, the Talmud.

The history of the Talmud begins at Mount Sinai, when God dictated the Written Torah to Moses. At that same time, God also gave Moses the Oral Torah. The written version of the Oral Torah is called the Talmud.

Compare the situation to the United States Constitution and the decisions of the Supreme Court. The Court interprets the words of the Constitution and shows how to apply them to reality.

Introducing Rashi: The Great Commentator of the Talmud

If you want to study Talmud, you need to get familiar with Rashi (1040–1105 CE). The name Rashi is actually an acronym for his full name, RAbbi SHlomo Itzchaki (SHLOW-mow Itz-KHAH-Kee). The shorter form is more convenient to say and write. (See the sidebar “Important Rabbis from History Known by Acronyms,” in this chapter, for more abbreviated names in Jewish culture.)

In the standard edition of the Talmud, Rashi’s commentary has appeared on every page since the 16th century. Rashi’s Talmud commentary reflects his ability to explain complexities in simple, straightforward, concise language. His commentary made Talmud study far more accessible and reached many people. In addition to his Talmud commentary, Rashi also provided a well-known commentary on the Torah.

The word commentator in this context simply means someone who helps to explain what the text means. If Rashi thinks that the reader might need some clarification, he makes a comment. In a Talmud class, the teacher often says, “What’s bothering Rashi?” This question refers to a comment by Rashi that offers some explanation of the Talmud’s text.

Scholar, rabbi, and vintner

Rashi was born in 1040 in Troyes, France. His father, Yitzchok (YITZ-khahk; Isaac), was a great rabbinical scholar. In addition to being a rabbi, Yitzchok was a vintner; Rashi also worked as a vintner.

In Jewish custom, you begin your Torah studies at the age of 5; and legend says that, at that young age, Rashi was already beginning to show evidence of great scholarship. In his teens Rashi left his home to study in Germany’s famous yeshivas (yeh-SHEE-vahz; Jewish schools), in both Mainz and Worms.

One of the most illustrious rabbis in all of Jewish history was known as Rabbeinu Gershom (“our teacher Gershom, Rah-BAY-new GUHR-shum) known as “the Light of the Exile”). Two of his disciples, Rabbi Yitzchok ben Yehuda and Rabbi Yaakov ben Yakar acted as Rashi’s main teachers.

After studying in Germany for eight years, Rashi returned to Troyes. At about 25, he was appointed to the community’s rabbinical court. When he was about 30, he established his own yeshiva in Troyes. The finest students from all over Europe came to study there, and Rashi became known as a superb teacher and authority on Jewish law. Rashi’s work earned him the title (Rabban Shel Yisrael, RAH-bahn shell yis-row-ale, the Teacher of the Jewish People.