18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

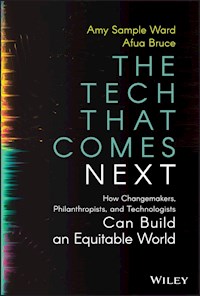

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Changing the way we use, develop, and fund technology for social change is possible, and it starts with you. The Tech That Comes Next: How Changemakers, Philanthropists, and Technologists Can Build an Equitable World outlines a vision of a more equitable and just world along with practical steps to creating it, appropriately leveraging technology along the way. In the book, you'll find: * Strategies for changing culture and investments inside social impact organizations * Ways to change technology development so it incorporates more of society * Examples of data, security, and privacy laws and policies that need to change to protect vulnerable populations and advance positive change Ideal for nonprofit leaders, social activists, policymakers, technologists, entrepreneurs, founders, managers, and other business leaders, The Tech That Comes Next belongs in the libraries of anyone who envisions a world in which technology helps advance, rather than hinders, positive social change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 350

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

WHY US?

WHY THIS BOOK?

WHO IS THIS BOOK ABOUT?

WHAT DO WE DREAM OF?

Chapter One: Where We Are and How We Got Here

WE LIVE IN A WORLD OF TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGY TO SUPPORT SOCIAL CHANGE

NOTES

Chapter Two: Where Are We Going?

OUR VISION

TECHNOLOGY THAT IS ACCOUNTABLE TO COMMUNITY

WHAT WILL IT TAKE TO GET THERE?

NOTE

Chapter Three: Changing Technology Culture and Investments Inside Social Impact Organizations

CASE STUDY: RESCUING LEFTOVER CUISINE

INSIDE THE PRACTICE OF CHANGE

QUESTIONS FOR WHAT'S NEXT

NOTES

Chapter Four: Changing Technology Development Inside and for Social Impact

CASE STUDY: JOHN JAY COLLEGE

DEVELOPING TECHNOLOGY FOR SOCIAL IMPACT ORGANIZATIONS

BUILDING NEW MODELS FOR TECH DEVELOPMENT

QUESTIONS FOR WHAT'S NEXT

NOTES

Chapter Five: Changing Technology and Social Impact Funding

CASE STUDY: OKTA FOR GOOD

INSIDE THE PRACTICE OF CHANGE

QUESTIONS FOR WHAT'S NEXT

NOTES

Chapter Six: Changing Laws and Policies

CASE STUDY 1: NATIONAL DIGITAL INCLUSION ALLIANCE

CASE STUDY 2: RURAL COMMUNITY ASSISTANCE PARTNERSHIP

INSIDE THE PRACTICE OF CHANGE

QUESTIONS FOR WHAT'S NEXT

NOTES

Chapter Seven: Changing Conditions for Communities

CASE STUDY: ATUTU'S PROJECT SUNBIRD

INSIDE THE PRACTICE OF CHANGE

QUESTIONS FOR WHAT'S NEXT

NOTES

Chapter Eight: Start Building Power for What's Next

START BUILDING POWER WHERE YOU ARE

STRUCTURE ORGANIZATIONS TO SUPPORT NEW MODELS

GET STARTED

NOTES

Chapter Nine: Where Will You Go Next?

A COMMUNITY‐CENTERED FUTURE IS POSSIBLE

WHAT WE NEED

WHAT WE VALUE

WE CAN BUILD TOGETHER

NOTE

Chapter Ten: Resources for What Comes Next

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

QUESTIONS TO ASK OTHERS

RECOMMENDED READING & ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Begin Reading

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1 Current State: Systemic Exclusion

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1 Future State: Systemic Inclusion

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

Amy Sample Ward

Afua Bruce

THE TECH THAT COMES NEXT

How Changemakers, Philanthropists, and Technologists Can Build an Equitable World

Copyright © 2022 by Amy Sample Ward and Afua Bruce. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data is Available:

ISBN: 9781119859819 (Cloth)

ISBN: 9781119859826 (ePub)

ISBN: 9781119859833 (ePDF)

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: © The7Dew/Getty Images

To the NTEN team: Andrea, Ash, Dan, Drew, Eileigh, Jarlisa, Jeremy, Jude, Karl, Leana, Michelle, Pattie, Samara, Thomas, and Tristan: You inspire me every day and remind me that together we can change ourselves and our world.

—Amy

To the many friends and colleagues and mentors who have encouraged me over the years to pursue making a difference at the intersection of technology and community;

To my parents, who taught me at a young age what it means to be a part of a community, and to my sisters, who have always kept me humble;

Thank you.

—Afua

Acknowledgments

This book was written and edited on the unceded traditional territories of the Cowlitz, the Clackamas, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians; the Nacotchtank (Anacostan) and the Piscataway; and the Ohlone, Muwekma, and Ramaytush peoples—the original and rightful stewards of the lands also known as Portland, Oregon; Washington, DC; and San Francisco, California. To the Indigenous communities who were here before us, those with whom we live today, and the seven generations to come, we are grateful for your leadership and stewardship. To our non‐Indigenous readers, the work we do and that we discuss in this book requires that we be committed to the process of truth and reconciliation so that we can make a better future for all. We ask you to join us in that commitment, and we encourage you to learn more about the native land where you live, work, and explore, and to support the Indigenous communities in your area. (Learn more at www.native-land.ca.)

We recognize the access to insights, research, and experiences we have and that we have brought to this book because of our current work at NTEN, where Amy is the CEO, and DataKind, where Afua is the Chief Program Officer. While our work has enabled us to learn and grow, it has also informed many of our ideas and our hope for what is possible for the future.

Deep gratitude both to Kirsten Janene‐Nelson for doing more than editing our work and truly partnering with us to convey our ideas as well as possible, and to Michelle Samplin‐Salgado for helping us find ways to use visualizations to bring ideas to life beyond words. Thank you to both of you for contributing your talents and heart in this project.

Thank you to all of the individuals we interviewed for sharing your ideas and experience with us. Thank you to the artists who made their illustrations and fonts available for use, including Natalia Nesterenko for the characters and Tré Seals of Vocal Type Co. for the Bayard typeface. Your work inspires us. Your work matters. You matter.

Thanks to the many individuals, especially women of color, who have worked so hard to study the ways people have been harmed or overlooked by mainstream technology development—and then to reveal their findings and advocate for change. This necessary work inspires us, protects everyone, and pushes technology to be relevant and responsible to all.

This book would not have been possible without the dedication, service, and contributions to the field of all those quoted and highlighted here—as well as the contributions of the multitudes of others whose work actively makes our world better.

We want to acknowledge the privilege we have in being able to put this book together. We also acknowledge that our thoughts, ideas, and recommendations are inherently informed by the long journey toward equity that has been led by Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color, by disabled people, LGBTQIA2+ people, immigrants and refugees and their children, poor people, tired people, and so many others. We can do our work today only because of the struggles and victories for rights that so many have dedicated their lives to—and we do this work now in service to the changes we know are possible when we work together.

Introduction

Welcome. Thank you. And hello.

We wrote this book for everyone; or, rather, for anyone. For anyone who thought there could be another way, there could be better outcomes, there could be different models to try. We hope that is you, so, welcome. And thank you for being here.

In the many conversations we have had with practitioners across many sectors during the development of this book, we found ourselves repeating a number of the same points about how to talk about the organizations, people, and systems involved in the work of using and building technology for changing the world. In the same spirit of those open and honest conversations, we want to invite you into some of the thinking and framing that shaped this book.

WHY US?

Both of us have worked in a diversity of spaces, including advocacy organizations, government, industry, and nonprofits—in the fields of philanthropy, capacity‐building, and policymaking. Through our work as strategists, organizers, researchers, technologists, and policymakers, we have focused on the ways that technology can power services and programs that benefit the communities where we live and all around the world. Between us we have been part of every stage of technology development—from design to testing to failure to trying again.

Although we are different people with different lived experiences, privileges, and perspectives, we share these same beliefs:

Since humans create technology, it can't be neutral.

Therefore, the opportunity and challenge is to more intentionally, inclusively, and collaboratively build the technologies that come next so they can support us in the bigger work of building an equitable world.

The only way we can truly make this happen is to use models that are built on community‐centered values.

We are practitioners, and we hope to always be. Every day we are in the practice of changing ourselves so that we can change the world. We invite you to be a practitioner too. That calls for always learning, testing, reflecting, and practicing the ways we can stretch ourselves and our teams and our systems to bend in new ways. This work can be started anywhere, in whatever space you are in today.

WHY THIS BOOK?

We did not want to make a “how to” book. We did not want to suggest that doing things differently—that changing organizations, funding institutions, and systems—is easy, or that there could be a checklist for making an equitable world. There's no easy way to change the systems and practices that have created the imperfect technologies we have today.

What we did want was to use the opportunity to write a book as a platform to uplift as many people as we can. We invite you to learn more about the work of those quoted and referenced throughout the following chapters.

Truly creating an equitable world will most certainly require contributions from everyone in some way. As this book is a practice in thinking about new options and priorities, we also want it to be a practice in looking for inspiration from a diversity of other efforts and acknowledging the lessons that many different people may offer us. There are so many more people, projects, organizations, and leaders that we wish we could have included, but we could never have made an exhaustive list.

Instead, we invite you to share, promote, and support the list of people and projects you know and have learned from in your work with others. We invite you to uplift folks in your community. Introduce them to others, recommend them for grants and investment, collaborate with them on new ideas, and invest in relationship‐building—just for the sake of doing so. As everyone does this more and more, we will collectively accelerate the learning and new connections that can help us move forward.

WHO IS THIS BOOK ABOUT?

We focus on five key groups that for now we are identifying as follows: social impact organizations, technologists, funders, policymakers, and communities. And while we use these titles for the groups, we acknowledge that there are many different terms and titles in use for all of these groups, and that we have little language that feels comprehensively accurate. Our language is always evolving and we look forward to the emergence of better terms that more accurately reflect the realities for folks in these groups. And, part of our vision for what comes next is a world where these groups are not siloed or separated in the way they often are today. Belief systems about where resources are accumulated and how they are distributed, who has access to training and decision making, and what work is worthy of investment are core to what will be changed so that we can organize and collaborate in new ways. We need to shift how we make change, how we resource communities, and how we build tools. Doing so will help us let go of the language that doesn't serve us, and from that new reality will come better terms.

Social Impact Organizations:

This is the most challenging term for us because it is so clearly inadequate to all that is accomplished by these organizations. Using a term like nonprofit, charity, or nongovernmental organization (NGO) would have implied that we were focused on a specific country or culture. The term “social change” has different connotations for different communities, and “civil society” is used in varying ways. Though we could argue that every organization, technology, and product has an impact—positive or negative—we decided to use “social impact organizations” to refer to the diverse set of entities who operate with a social benefit mission. We know that US 501(c)(3) registered nonprofits are not the only ones who meet this definition; other entities such as associations, charities, NGOs, and even public benefit corporations may also be part of this work.

Technologists:

We regularly talk about how, at this point in time, anyone could be considered a technologist. So it was naturally difficult for us to separate those creating software and applications from those with no coding experience who nonetheless use and manage technologies. In this book we use “technologists” to indicate those who develop technology—whether they do it in proprietary systems or open source; as a staff person of a social impact organization or a technology company; or as a purpose‐built system for social impact or for the commercial market.

Funders:

There are many terms for funders that are intended to mean many different things to different people. We did not want to write about only private philanthropy, venture capital, corporate social responsibility programs, or individual major donors. Our choice to use “funders” was to create an intentional umbrella over all of the ways that social impact work, community initiatives, and technology projects are and could be financially resourced.

Policymakers:

Each of these terms is challenged by regional and geographic nomenclature, but perhaps none as much as “policymakers.” In this book we talk about projects that may be on a neighborhood scale or a global scale, so referring to mayors, counselors, cabinet members, or anything else would inherently limit how we discuss these ideas. Similarly, we want to open up space in recognizing that not all policies are created by elected officials—there are appointed officials, departments authorized to set policy, and more. We use “policymakers” inclusively for all those in a position to create policies that impact technology, social impact work, and all of our communities.

Communities:

What someone might mean when they use the word “community” will vary by the person, their intention, and the context of the conversation. Community is critically important to what we talk about here, and what we mean by the word “community” is often, if not always, subjective. Who is your community? You likely have several: communities of shared identity, communities of place, communities of interest, and more. No one has only one community; we hope you will keep in mind the plurality of communities in and around all of us as you read the following chapters.

These aforementioned groups and terms are separated for the sake of direct discussion about opportunities and needs. Of course, a single person could be represented by all five terms: someone who works in a social impact organization as a technologist could receive a grant to distribute funds, could educate a policymaker on the data from their research, and then engage with their community to advocate for change. We are, each of us, full and complex people—as you read, you may find that you have been or are now part of each of these groups in different ways and at different times. The fluidity of our lived experiences manifests in the ways we have, or have access to, power in some of these groups but not others. We hope to shift toward a world that doesn't create barriers between these groups. But even before that day, today, together, we have all the resources we need to make any world possible.

WHAT DO WE DREAM OF?

People sometimes think technology is the way to address inequality. We don't think that, and that's not what we suggest in this book. In fact, that's not what our decades of experience with myriad organizations across sectors has taught us. Technology is a tool and nothing more; it's people who have ideas and solutions. As Octavia Butler said, “There is no single answer that will solve all our future answers, there is no magic bullet, there are thousands of answers, and you could be one of them, if you choose to be.”

In asking for you and others to dream and imagine something different from what we have today, we want to acknowledge the privilege that it is to have the space for that dreaming. We have that space because we don't need to figure out where we'll get our next meal or a bed, or find medicine or support, or access care or safety. So, that's what we dream of:

That we all have space to rest.

That we all have space to collaborate.

That we all have space to build relationships.

We don't ask communities to do the labor to undo the oppressive systems around them. We dream about self‐determination for communities and community members.

We don't want to perpetuate work that follows old expectations or dominant priorities. We dream about community‐centered work that builds from community‐centered values.

This book is an exercise in doing that dreaming. We ask questions to prompt your thinking even beyond what is written here. We need more imagination, and we need more people doing that imagining together.

Chapter OneWhere We Are and How We Got Here

Technology. Just the word itself evokes a range of emotions and images.

For some, technology represents hopes and promises for innovations to simplify our lives and connect us to the people and issues we want to be connected to, almost as though technology is a collection of magical inventions that will serve the whims of humans. To others, technology represents expertise and impartial arbitration. In this case, people perceive that to create a solid technological solution one must be exceptionally smart. Technology, with this mindset, is also neutral, and therefore inherently good because it can focus on calculated efficiencies rather than human messiness. Others have heard that technologists “move fast and break things,” or that progress is made “at the speed of technology”—and accordingly associate the word “technology” with speed and innovation constantly improving the world and forcing humans to keep up.

In contrast, the mention of “technology” fills some people with caution and trepidation. The word can conjure fears and concerns—fueled by movies and imaginations—of robots taking over the world and “evil” people turning technology against “good” people. Others are skeptical of how often technology is promised to solve all problems but ends up falling short—especially in the many ways it can exclude or even inflict physical, emotional, or mental harm. Unfortunately, there are many examples of technology making it more difficult for people to complete tasks, contributing to feelings of anxiety or depression, and causing physical strain in bodies. The potential for these and other harms are what cause some to be concerned or fearful about technology. And, for some, the mention of technology stokes fears of isolation: for those less comfortable with modern technology, the fear of being left out of conversations or of not being able to engage in the world pairs with the very practical isolation that lack of access can create.

Many people hold a number of these sometimes contradictory emotions and perspectives at the same time. In fact, individuals often define “technology” differently. Although some may think of technology as being exclusively digital programs or internet tools or personal computing devices, in this book we define “technology” in the broadest sense: digital systems as well as everything from smart fridges to phones to light systems in a building to robots and more.

WE LIVE IN A WORLD OF TECHNOLOGY

Regardless of how complicated feelings about tech may be, we all must embrace it: we live in the age of technology. Whether you consider how food travels from farms to tables, how clothes are manufactured, or even how we communicate, tech has changed and continues to change how these processes happen. Certainly, we complete a number of services through technology systems—shopping for clothes, ordering weeknight meals, scheduling babysitters, and applying for tax refunds. We expect the technology tools and applications we use to provide smooth and seamless experiences for us every time we use them. In many cases, with the exception of the occasional glitch or unavailable webpage, technology works how we expect it to; it helps us get things done.

Unfortunately, not everyone has the same experiences with technology. The late 1980s brought us the first commercially available automatic faucets, which promised relief for arthritic hands and a more sanitary process for all. Some people reported sporadic functioning, however; the faucets worked for some but not others. When the manufacturers researched the problem, an unexpected commonality appeared: the faucets didn't work for people with dark skin. In an engineering environment dominated by white developers, testers, and salesmen—and we deliberately choose the suffix “men”—people with dark skin had not been included among the test users. In a more recent example, in 2016 Microsoft launched @TayAndYou, a Twitter bot designed to learn from Twitter users and develop the ability to carry on Twitter conversations with users. Within one day, Microsoft canceled the program, because, as the New York Times stated, the bot “quickly became a racist jerk.”1

In the name of efficiency and integrity, various technology systems are developed and implemented to monitor the distribution of social benefit programs. Organizer and academic Virginia Eubanks, who studies digital surveillance systems and the welfare system, has remarked that, for recipients of welfare programs, “technology is ubiquitous in their lives. But their interactions with it are pretty awful. It's exploitative and makes them feel more vulnerable.”2 Technology is used to automatically remove people who are legally entitled to services from systems that furnish government and NGO providers with data regarding the population that needs those services. In her book Automating Inequality, Eubanks describes a state‐run health care benefits system that began automatically unenrolling members, and the associated volume of work individuals had to do to understand why they were, often wrongly, unenrolled and how to reenroll. It is also used to prevent someone from receiving services in one part of their lives because of a disputed interaction in a different part of their lives. In this case, notes on unsubstantiated reports of child abuse may remain in a parent's “file,” and then used to cast suspicion on the adult if they seek additional support services. This is all tracked in the same government system.

“The technology has unintended consequences” is something many people in technology companies say when referring to products that don't work for a segment of the population, or to systems that leave people feeling exploited. However, these “unintended consequences” are often the same: they result in excluding or harming populations that have been historically ignored, historically marginalized, and historically underinvested in. The biases and systems that routinely exclude and oppress have spread from the physical world into the technological world.

How can we have these uneven, unequal experiences with technology when one of the supposed attributes of technology is impartiality? Isn't tech based on math and science and data—pure, immutable things that cannot change and therefore can be trusted? There are so many examples of how technology, regardless of how quickly it moved or innovated, repeatedly did not deliver on the hopes and promises for all people. Why?

We're not the first to ponder these questions. Many people, including ourselves, have concluded that technology is put into use by humans and, accordingly, is good or bad depending on the use case and context. Technology is also built by humans and, as a result, technology reflects the biases of its human creators. Melvin Kranzberg, a historian and former Georgia Tech professor of history of technology, in 1986, wrote about Six Laws of Technology, which acknowledge the partiality of technology within the context of society:3

Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.

Invention is the mother of necessity.

Technology comes in packages, big and small.

Although technology might be a prime element in many public issues, nontechnical factors take precedence in technology‐policy decisions.

All history is relevant, but the history of technology is the most relevant.

Technology is a very human activity—and so is the history of technology.

These laws are still applicable today. Technology, it turns out, is fairly useless on its own. High‐speed trains would be irrelevant in a world without people or products to move. A beautifully designed shopping website is a waste if no one knows about or uses it. Technology exists within systems, within societies. The application of math and science, as well as the structure and collection of data, are all human inventions; they are all therefore constructed to conform to the many rules, assumptions, and hierarchies that systems and societies have created. These supposedly impartial things, then, are actually the codification of the feelings, opinions, and thoughts of the people who created them. And, historically, the people who create the most ubiquitous technology are a small subset of the population who happen to hold a lot of power—whether or not they reflect the interests and feelings, opinions, and thoughts of the majority, let alone of the vulnerable.

IDA B WELLS Just Data Lab founder and author of the book Race After Technology, Princeton University Professor Ruha Benjamin takes it a step further. Because technology and systems are often built on these biased assumptions, “Sometimes, the more intelligent machine learning becomes, the more discriminatory it can be.”4

What constitutes “technology” has evolved over time. Roughly shaped knives and stones used as hammers are widely considered the first technological inventions.5 Fast‐forward several millennia to the creation of a primitive internet. What started as a way for government researchers to share information across locations and across computers grew into the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network in the 1960s. From there, additional large and well‐funded institutions, such as universities, created their own networks for researchers to share information. Next, mainframes—large computers used by companies for centralized data processing—became popular. With the creation of a standard communication protocol for computers on any network to use, the internet was born in 1983.

Since then, the pace of technology development has only accelerated. The spread of personal computers and distributed computing meant that more individuals outside of institutional environments had access to technology and to information. People quickly created businesses, shared ideas, and communicated with others through the “dot‐com” boom of the 1990s. We have more recently seen the rise of cloud computing, on‐demand availability of computing power, and big data—the large amount of complex data that organizations collect. Techniques to process this data, learn from it, and make predictions based on it are known as data science, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. As a result, we now have a world where many people have access to a tremendous amount of computing power in the palm of their hands; companies can understand exactly what people want and create new content that meets those desires; and people can envision technology touching, and improving, every aspect of their lives.

In less than a century, we have gone from creating the internet to sending people to the moon with mainframe technology to building smartphones with more computing power than what was used to send people to the moon. And as technology has evolved, so evolve those who develop the technology—the “technologists.” Unfortunately, whereas technological developments increase the percentage of the population who can engage with it, the diversity of technologists has decreased. The large tech companies are overwhelmingly filled with people who identify as white and male, despite the reality that this group doesn't comprise the majority percentage of humans on earth. But the technology field hasn't always been this way. The movie Hidden Figures, based on the book by Margot Lee Shetterly, told the story of the African American women of West Area Computers—a division of NACA, the precursor of NASA—who helped propel the space race by being “human computers” manually analyzing data and creating data visualizations. US Navy Rear Admiral Grace Hopper invented the first computer compiler, a program that transforms written human instructions into the format that computers can read directly; this led to her cocreating COBOL, one of the earliest computing languages. Astonishingly, the percentage of women studying computer science peaked in the mid‐1980s. We know, intuitively, that talent is evenly distributed around the world, and yet an enduring perception in tech is that the Silicon Valley model is the epitome of success. The Silicon Valley archetype, in addition to still being predominantly white and male, also privileges individuals who can devote the majority of their waking hours to their tech jobs—and who care more about moving fast than about breaking things. The archetype emphasizes making the world conform to their expectations, rather than using the world's realities to shape and mold their own products. And with a purported state of the world being defined by a smaller proportion of the population, the technology being constructed creates an ideal world for only a limited, privileged few.

TECHNOLOGY TO SUPPORT SOCIAL CHANGE

It's against a backdrop of all of these factors—the complicated and sometimes inaccurate feelings about technology, the significant benefit that technology can provide, the reality that technology isn't neutral—that conversations about tech created for and in the social impact sector begin.

For the purposes of this book, we define the “social impact sector” as the not‐for‐profit ecosystem—including NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) and mutual aid organizations and community organizers—that promotes social or political change, often by delivering services to target populations in order to both improve communities and strengthen connections within societies. As the name implies, organizations in the social impact sector don't make a profit, but rather apply all earned and donated funds to the pursuit of their mission. Social impact sector organizations can vary in size and scope, from a few people in one location to thousands of people around the world. A common aspect of these mission‐driven organizations is that they focus on the mission first—feeding hungry children, promoting sustainable farming, delivering health care equitably, and more.

Often, practitioners start and lead these organizations because of their knowledge of the social or political issue and their ability to deploy resources to make an impact. This focus on serving the defined clients, combined with the pressure to show that the funds received are directly affecting those who need the support, rather than being allocated to cover administrative overhead, the category that technology services often fall into. The technical and interconnected world in which we live, however, requires that to remain relevant and effective, the social impact sector must embrace technology to deliver its services—a necessity that has existed for quite some time. But given the global phenomenon of COVID‐19 and what it has wreaked, the challenges of operating, organizing, and delivering services during a pandemic have revealed that, in terms of what needs to happen now in the social impact sector, and certainly what comes next, technology must be deeply integrated into how these organizations conduct business.

One of the many ways the pandemic has stressed our society is in significantly changing people's economic status. Although some have profited as the virus and its variants have spread and claimed lives across the globe, many, many more have lost not just accumulated wealth but also vital income. Service providers have struggled to keep up with the vast increase of those in need. And we will not quickly recover; it is predicted that a number of nonprofits will no longer exist five years after the worst of the pandemic has passed. Nonprofits have no choice but to be more efficient.

But the onus isn't solely on the social impact organizations themselves; many technologists have not considered the social impact sector an applicable setting for their talents. Fewer are inspired to take the time and care to advance complicated social issues for the benefit of one's fellow humans, and even fewer actively work to minimize any harm to individuals that the technology could cause. And, even when technologists do want to support the social impact sector, they often don't know how to support it in helpful ways. As Meredith Broussard wrote in her book Artificial Unintelligence, “There has never been and never will be a technological innovation that moves us away from human nature.”6 The social impact sector reminds us that human nature is to live in community.

When we unpack what it means to be a technologist in the social impact sector, we have to start with the basics. We must understand that technology in social impact organizations is expansive. It includes IT systems, management systems, and products to help the organization deliver services to its clients and supporters. IT systems include tech such as broadband internet, computers and mobile devices, printers, and computing power. Management systems include donor databases, impact tracking systems, performance dashboards, and customer relationship management systems. Products that support service delivery could include a custom‐built website to allow people to schedule visits with a caseworker, a route‐optimization tool that plans the most efficient delivery routes, algorithms to ensure data integrity in training software, or a tool that processes and presents data to inform policymakers as they legislate. As you can see, this breadth of technology requires a variety of different skills to execute. Add to which—given that the social impact sector exists to improve lives, the security and privacy that organizations implement in their program designs need to be considered in every aspect of the technology design.

The significant issues the social impact sector tackles, combined with the logistical challenges of reaching people in locations far and wide, requires deep technical expertise and sophisticated design. As this has not been readily available, social impact sector organizations have deprioritized and deemphasized technology for decades. But the current climate is such that those organizations must have technology appropriate to their context, even if it isn't the fanciest technology. This can be a significant challenge—good and bad—for “expert” technologists who are used to entering new environments as tech saviors with an understanding that their expertise will immediately translate into a new space. When speed and immediate contributions are prioritized, the work needed to prevent harmful unintended consequences is often neglected. There is no space for the “tech savior” mindset in the social impact sector, nor for technologists inclined to quickly jump into developing tech because they've developed tech elsewhere. The social impact sector has its own expertise—and, while technical skills are transferable, understanding of social problems and community contexts is not. Even within the social impact sector, “design with, not for” has been a mantra of the civic tech world for years, but this idea alone is insufficient. Designing with, not for does not transfer ownership of information and solutions; long‐term ownership, with the ability to modify, expand, or turn off the solutions, is necessary for communities to maintain their own power.

The recognition that expertise does not magically transfer between sectors is only one of the design constraints for developing technology within the social impact sector. Though the sector benefits from government funding, it relies primarily on philanthropic funding. As a result, technology budgets in the social impact sector are perennially tight, leaving tough decisions about whether to develop a more costly custom solution that meets and respects client needs or buy a ready‐made, imperfect solution that reaches more clients. When assessing off‐the‐shelf technology, social impact sector leaders recognize that deploying technology that has a track record of marginalizing and disenfranchising people—such as video conferencing software without closed captioning, making it difficult to use by the Deaf community—will not work for organizations that serve historically marginalized and disenfranchised populations. In addition, because these organizations often deal with different populations with immediate needs, they don't have the luxury of adopting an “if you build it they will come” mindset, or of deploying a solution that benefits only a portion of their clients simply because it was too difficult to develop something for everyone.

Even once all these factors are addressed, organizations then need to figure out what should happen next. How do they plan for and carry out system maintenance and upgrades? Is what was done relevant only to the particular organization, or is it something that others in the social impact sector can also benefit from? Given their mission‐driven nature, many organizations turn their focus back to their direct clients before answering these questions. The “technology versus client support” consideration is a false dichotomy, but it is one that many social impact sector organizations feel nonetheless.

This Is Where We Are

Figure 1.1 illustrates the factors today that don't serve us; it depicts the current state of systemic exclusion. Most resources are difficult to access, as though behind a fence. Even if a person is able to gain entry to the general location with resources, for the average individual, the resources are siloed—people and functions and services happen separately and without coordination. If someone is not already in a silo, they encounter systems of control and are denied entry to exclusive, elite spaces.